Manumission: Free at Last (or perhaps not?)

If you’ve researched Southern slave-holding ancestors, you may be aware of the term “manumission”. If not, it simply means the act of freeing one’s slave(s). As such, manumission differed from emancipation set forth by government proclamation, Abraham Lincoln’s 1863 Emancipation Proclamation being a prime example.

Manumission was not a new concept to American slave owners. It’s almost as old as slavery itself. Aristotle thought slavery was quite natural and even necessary. And while there were varying degrees of slavery, all forms limited the Greek slave in one way or another, albeit with a modicum of certain rights extended just for being a human being.

Romulus, the founder and first king of ancient Rome, is thought to have begun the practice in that ancient society by granting parents the right to sell their own children into slavery. Romans would go on to enslave thousands through conquest.

As opposed to Greek slavery, as long as someone was a Roman slave they possessed no rights – none. But, following a slave’s manumission full citizenship rights were extended, including the right to vote.

American slavery was, however, racially-based and transcendent of those ancient traditions. For the American slave owner it was a matter of economics, as set forth in actuarial tables – a sort of justification for at least gradual manumission of slaves – published in The Pennsylvania Packet on January 17, 1774. A “neighboring province” had been recently considered justification for gradual manumission in the last legislative session.1

Virginia passed a law in 1782 following the Revolutionary War allowing slave owners to manumit at will without government approval. In part, perhaps this new law propelled Robert Carter III, one of the state’s wealthiest men, to begin freeing his slaves.

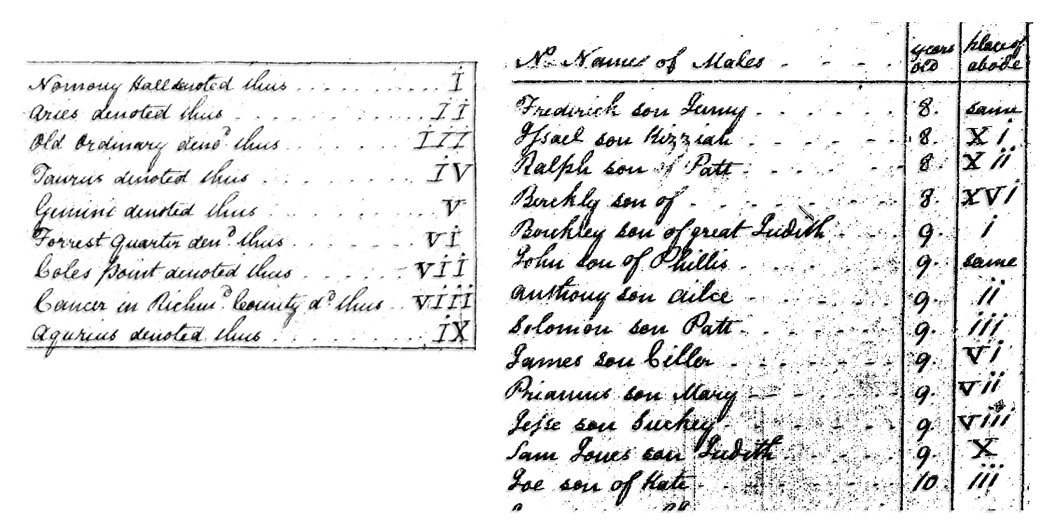

Some have surmised Carter underwent a religious conversion. By signing a Deed of Gift on August 1, 1791 and presenting the same in Northumberland District Court on September 5, he set in motion the gradual manumission of his considerable slave holdings. At the time he enumerated – each one by name and age – over 450 slaves. It is an extraordinary document and thought to have been responsible for the greatest number of slaves freed by one man in all of American history.

He began by providing a table of locations (spread over several counties) where his slaves lived, referencing each named slave with a specific location. He seems to have been intent on crossing all T’s and dotting all I’s.

By the time manumission was completed some three decades later, somewhere between 500 and 600 were thought to have been freed, albeit not without a bit of legal wrangling. In 1793 Robert Carter removed to Baltimore and left the measured and deliberate process in the hands of Baptist minister Benjamin Dawson. When Carter died in 1804 his heirs sued Dawson in order to halt manumission, but lost in an 1808 ruling in the Virginia Court of Appeals.2

This is just one example of the manumission of slaves, something which genealogists with slave-owning ancestors will find interesting. One of the most extraordinary cases occurred in Mississippi, one that was litigated for years before being settled in favor of two manumitted slaves. This article is excerpted from the January-February 2019 issue of Digging History Magazine. Purchase it here.

P.S. Speaking of manumission in Mississippi, there is an interesting story in the February 17, 2026 episode of Finding Your Roots on PBS which featured the ancestry of singer Lizzo. It makes the aforementioned Mississippi case even more interesting since apparently manumission was against the law in Mississippi.

Thanks for stopping by! For more stories like this one, consider subscribing to Digging History Magazine. Purchasing a subscription entitles you to subscriber benefits (20% off all services, including custom-designed family history charts) AND a chance to win your very own custom-designed family history chart! Details here (or click the ad below).

Thanks for stopping by! For more stories like this one, consider subscribing to Digging History Magazine. Purchasing a subscription entitles you to subscriber benefits (20% off all services, including custom-designed family history charts) AND a chance to win your very own custom-designed family history chart! Details here (or click the ad below).

Footnotes:

Must-See Documentary

For all my genealogy and history-loving friends . . . I discovered this documentary through Crista Cowan’s (“The Barefoot Genealogist”) podcast. If you’re a fan of Finding Your Roots on PBS, you will love this documentary which highlights an interesting (and moving — bring your tissues!) piece of American immigration history. You can watch for free on Tubi or rent through PBS on Amazon.

For all my genealogy and history-loving friends . . . I discovered this documentary through Crista Cowan’s (“The Barefoot Genealogist”) podcast. If you’re a fan of Finding Your Roots on PBS, you will love this documentary which highlights an interesting (and moving — bring your tissues!) piece of American immigration history. You can watch for free on Tubi or rent through PBS on Amazon.

By the way, Crista has a series, “Stories That Live in Us”, which is currently highlighting all states in a lead-up to America’s 250th birthday. The series started with Hawaii, the 50th, and is working back to America’s beginnings. This week was Mississippi. You can find her podcast on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/@CristaCowan. Very interesting and informative series!

Free to Enslave?

The premise may seem unbelievable, given what our history books have always taught us. It is true – there were free men and women of color who owned slaves. The question is, why would someone previously enslaved choose to enslave others?

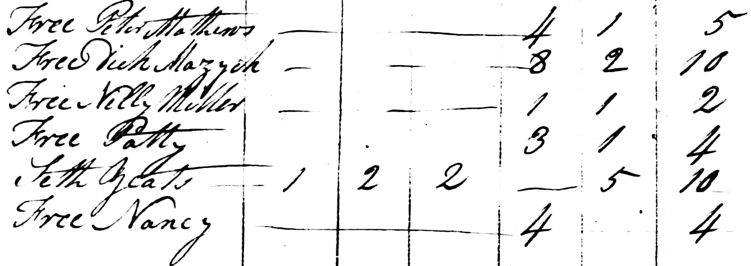

In 1790 in the St. Phillip’s and St. Michael’s Parish of Charleston, South Carolina, a number of free persons of color (male and female) were enumerated as such by “Free” appearing before their given name. A number of these free blacks also owned slaves.

In this particular extracted section, four out of five of the free persons of color owned slaves (next to last column is number of slaves owned), in an aggregate amount equal to the number of slaves owned by Seth Yeats, presumably a white person. According to Larry Koger, author of Black Slaveowners: Free Black Slave Masters in South Carolina, 1790-1860, there were 36 black slave masters enumerated in Charleston City in 1790. Furthermore, Koger asserts that Peter Basnett Mathews (enumerated as “Free Peter Mathews”) “bought slaves only to emancipate them and asked nothing in return for their acts of benevolence.”3

The slave owned by Mathews in 1790 is said to have been a black man named Hercules, “who was acquired for humanitarian reasons and later emancipated by the colored man.”4 Mathews, a butcher by trade, was one of a number of free black artisans of Charleston who often challenged the societal status quo. He drew attention to South Carolina’s new constitution which provided for Bills of Rights, available to all free citizens, excepting those of the Negro race. Peter, along with another butcher named Matthew Webb and Thomas Cole, a bricklayer and builder, petitioned the South Carolina Senate for redress.

Even though they were free citizens and taxpayers, as well as peaceful contributors to society, they were denied trial by jury and sometimes subjected to “unsworn testimony of slaves.”5 Fifty years after passage of the state’s Negro Act of 1740 which made it illegal for slaves to assemble, raise their own food, earn their own money or learn to write, free Negroes were still being discriminated against simply because of the color of their skin. Not surprisingly, the Senate rejected their petition.

In 1793 Peter Mathews’ home and papers were searched when state officials feared a black uprising. He certainly had nothing to hide and cooperated fully. What sort of papers might Mathews have possessed?

An extensive account of his ancestry (or, at least it seems to be implied) is provided within the voluminous research presented in a two-volume book entitled, Free African Americans of North Carolina, Virginia, and South Carolina, From the Colonial Period to About 1820, by Paul Heinegg. Peter Mathews is briefly mentioned at the end of the Matthews family history, perhaps because the author was unsure of just where (or if) in the family line he belonged.

Nevertheless, if Peter was indeed part of this line of free Negroes, the family’s history is believed to have begun with Katherine Matthews, “born say 1668, was a white servant woman living in Norfolk County [Virginia] in June 1686 when she was presented by the grand jury for having a ‘Mulatto’ child. She may have been the ancestor of . . .”6 (followed by a long enumeration of possible descendants). If this assumption is correct, it is possible all of Katherine’s mulatto children were considered free since laws at the time (passed in 1662) stated that a person of color was either free or slave based on the mother’s status.

Peter Basnett Mathews died in 1800 and wrote a will expressing his final wishes in regards to bequeathing what worldly goods he had accumulated to his wife Mary and their children. The opening paragraph indicates his status as a “Man of Colour and Butcher by Trade” There is no mention of slaves, as presumably all he may have ever owned were by then emancipated.

Peter Mathews is just one example. One former enslaved family had the distinction of being South Carolina’s largest slave-owning operation. This article is from the archives, the January-February 2019 issue of Digging History Magazine. Purchase it here.

Thanks for stopping by! For more stories like this one, consider subscribing to Digging History Magazine. Purchasing a subscription entitles you to subscriber benefits (20% off all services, including custom-designed family history charts) AND a chance to win your very own custom-designed family history chart! Details here (or click the ad below).

Thanks for stopping by! For more stories like this one, consider subscribing to Digging History Magazine. Purchasing a subscription entitles you to subscriber benefits (20% off all services, including custom-designed family history charts) AND a chance to win your very own custom-designed family history chart! Details here (or click the ad below).

Footnotes:

Seawillow: What’s in a Name?

Seawillow

Seawillow is a rather lyrical and poetic sounding name isn’t it? I ran across this name while researching a friend’s African American ancestry. Where in the world did this name come from? Wouldn’t you just know – there’s a story behind it!

A search for the name at any newspaper archive site reveals the name appears to have been used most often by Texans – and rightly so, since the story from which the name evolved occurred around Beaumont in 1855. She was the very first baby girl given this special name.

October 22, 1855 must have been a stormy day to be born along the Neches River, which meanders southeast over 400 miles from eastern Van Zandt County, emptying into the Gulf of Mexico below Beaumont. Today, the area averages well over 40 inches of rain per year and flooding occurs on average every five years.

The day Reverend John Fletcher and Amelia (Rabb) Pipkin’s daughter came into the world was a perilous one as flood waters trapped them on a raft, along with several family slaves, the situation dramatically heightened since Amelia was about to give birth. The oft-told story is related at the Find-A-Grave page for Seawillow Margaret Ann Pipkin Wells [edited]:

The day Seawillow was born there was a disastrous flood on the Neches River in Beaumont, Texas. The Rev. John F. Pipkin and his pregnant second wife, Amelia Rabb, and some of the family slaves were swept along on a raft. Just before the birth of his daughter, a human chain was formed by the slaves to fasten the raft to a willow tree. The Reverend looked up through the branches of the Willow tree and gave thanks to God for the safe delivery of his daughter in the midst of the flood water. Thus, the name Seawillow.7

In 1942 one of John’s sons, Stephen Walker Pipkin, was interviewed and related how he was born in the family home “maintained on Briar Island”8, located in the southwest part of Orange County. S.W. had just purchased his father’s former ranch property.

John Pipkin had a significant influence all those years ago, earning the sobriquet “father of Beaumont churches.”9 For some time following his arrival from Arkansas in the early 1850s, he was the only preacher in those parts. Despite his staunch Methodist faith, he “was not guided by denominational fetters, but extended to all who needed wise counsel or humane help in sorrow, sickness or death, and who served at baptisms, marriages or funerals as the general ministrant of Beaumont.”10 Like many other preachers of the day John was bi-vocational, operating a saw mill and also served three terms as County Judge for Jefferson County.

John Pipkin had a significant influence all those years ago, earning the sobriquet “father of Beaumont churches.”9 For some time following his arrival from Arkansas in the early 1850s, he was the only preacher in those parts. Despite his staunch Methodist faith, he “was not guided by denominational fetters, but extended to all who needed wise counsel or humane help in sorrow, sickness or death, and who served at baptisms, marriages or funerals as the general ministrant of Beaumont.”10 Like many other preachers of the day John was bi-vocational, operating a saw mill and also served three terms as County Judge for Jefferson County.

John, the son of Reverend Lewis and Mary Pheraby (Beasley) Pipkin, was born in Sparrow Swamp, Darlington District, South Carolina on August 14, 1809. After his first wife died he married Amelia Rabb, a widow, in 1844 in Conecuh County, Alabama. By 1850 the family was living in Ouachita County, Arkansas.

After Amelia died on January 23, 1867 of pneumonia John’s married daughter, Nora Lee Holtom, wrote a letter to Stephen Warner Pipkin asking whether he could take Seawillow (or board her for a year) so she could attend school with her cousin Mary. John would gladly compensate for her care. However, by 1870 Seawillow was living with John and his new wife Mattie.

Seawillow grew up in Beaumont and later taught school in Caldwell County (Luling and Lockhart). On November 22, 1883 she married Littleberry Walker Wells. On February 22, 1886 their first daughter was born – Seawillow Lemon – and the first of several descendants named Seawillow.

The farming community where they lived continued to grow and by 1899 required a post office. It was named “Seawillow”. Littleberry died on January 30, 1900 and Seawillow on May 30, 1912, both buried in the Wells Cemetery in Seawillow.

My friend’s great grandmother, Seawillow Hubert, was born on December 14, 1880 in Orange County. Although I haven’t been able to find a direct connection to the Pipkin family, it’s certainly possible one of her ancestors was either a slave of John Pipkin’s or the story of how his slaves had helped save his daughter’s life became legend among slaves and former slaves.

Through the years, Seawillow Hubert’s name was spelled (or transcribed) variously as “Serilla”, “Suvilla”, “See William” or “Seawillow”. It was a bit difficult to discern what her actual name was, but this Seawillow’s Find-A-Grave entry clearly records her name. I had to know where that name came from, so thus the little “side adventure”.

Not only did I learn the likely origins of her name, I learned quite a bit of history about the Beaumont area and the Pipkin family. While I usually write these types of articles about surnames, this turned out to be quite interesting learning the history of someone’s forename.

As I always like to say, keep digging!

As I always like to say, keep digging!

Thanks for stopping by! For more stories like this one, consider subscribing to Digging History Magazine. Purchasing a subscription entitles you to subscriber benefits (20% off all services, including custom-designed family history charts) AND a chance to win your very own custom-designed family history chart! Details here (or click the ad below).

Thanks for stopping by! For more stories like this one, consider subscribing to Digging History Magazine. Purchasing a subscription entitles you to subscriber benefits (20% off all services, including custom-designed family history charts) AND a chance to win your very own custom-designed family history chart! Details here (or click the ad below).

Footnotes:

Reflections . . . Eight Years and Counting

I was recently reviewing stats for the blog, a gauge of how effective my recent return to regularly posting articles has been. I saw a stat for an article I wrote in 2018 on the occasion of the 25th anniversary of becoming a self-employed entrepreneur (originally began in 1993 as a computer consultant and programmer), less than a year after I began publishing Digging History Magazine, a (now) bi-monthly digital publication focusing on history and genealogy. The article, entitled “I Am Becoming . . . Therefore, I Must . . . “, began with:

To be a writer, one must write. And so, on October 1, 2018, the 25th anniversary of becoming a self-employed entrepreneur, I write. It’s not what I started out doing 25 years ago, yet I am slowly, but surely, pursuing my dream of becoming a writer. Honing my God-given skills. As long as you’re alive and kicking you can pursue your dreams. Therefore, I must continue to write.

I wondered whether I might someday write a book, since by that time I had “amassed a portfolio of several hundred articles” over the last few years (I began the blog in 2014). I had also taken the position of editor for my local genealogical society’s newsletter. I am proud to say that during my tenure as editor, the newsletter won awards, including first place with the Texas State Genealogical Society, and runner-up one year with a submission to the National Genealogical Society.

Producing each issue — taking on the roles of editor, researcher, publisher, writer and graphic designer (I do it all!) — is an arduous process. Nevertheless, I am always exhilarated when I finally finish an issue, which these days runs anywhere from 90-120 pages — no ads or “fillers”, just stories (and tips for finding the best records).

I am also a genealogist, helping people discover their roots. I have found that researching and writing the magazine makes me a better genealogist, my philosophy being that in order to be adept at one discipline (genealogy) one must be well-versed in the other (history). It’s cathartic in a way, writing about long ago events, making a connection with the past. I am there, and I attempt to take my readers there.

Back in 2018 I was reminded of an encouraging word from a subscriber:

This summer I made a new friend who purchased a three-month subscription, but just wanted to try it out. I cancelled the subscription so she wouldn’t be charged again three months later. However, something happened and she was mistakenly charged anyway. I emailed her right away to apologize and tell her I’d get her a refund if she still wanted to end her subscription. To my joyful surprise she emailed me back: “Please keep the subscription. I enjoy your magazine!” Was it perhaps kismet that she was mistakenly charged? I don’t know but those eight words were a much-needed pat on the back . . . keep writing.

And, she is still a faithful subscriber today! Along the way, I have received heartening feedback from subscribers, most recently: “I love your work! I learn a lot and am entertained.” I’m always encouraged when someone takes the time to give me a little “pat on the back.” It keeps me going. As I wrote back then, “I continue to write and publish and hope. I am a writer. Therefore, I will write . . . and write . . . and write.” It’s still true today!

If you love history, and maybe you’re curious about getting started with researching your family history, I hope you’ll consider a subscription. There are three budget-minded options: Annual, Semi-Annual and Quarterly. Article and issue samples are also available here. Questions? Email me at [email protected].

P.S. Purchasing a subscription entitles you to subscriber benefits (20% off all services, including custom-designed family history charts) AND a chance to win your very own custom-designed family history chart! Details here (or click the ad below).

What in Blue Blazes . . . happened to my ancestor’s record?

Family Tree Magazine (May/June 2018) called them “Holes in History” – destructive fires throughout United States history with far-reaching effects on modern-day genealogical research. It might have been the deed to your third great-grandfather’s land in Mississippi, your grandfather’s World War II service record, or the missing 1890 census records. This excerpted article published in the January-February 2020 issue of Digging History Magazine takes a look at the stories behind these devastating events and how to find substitute records.

ABOUT THOSE COURTHOUSE FIRES . . .

ABOUT THOSE COURTHOUSE FIRES . . .

Here’s something we can all agree on: nineteenth and early twentieth century courthouse fires are the bane of genealogists everywhere. Have you ever wondered why so many courthouse fires occurred in the latter half of the nineteenth century? Would it surprise you to find that many of them were set nefariously?

The Big Cover-Up

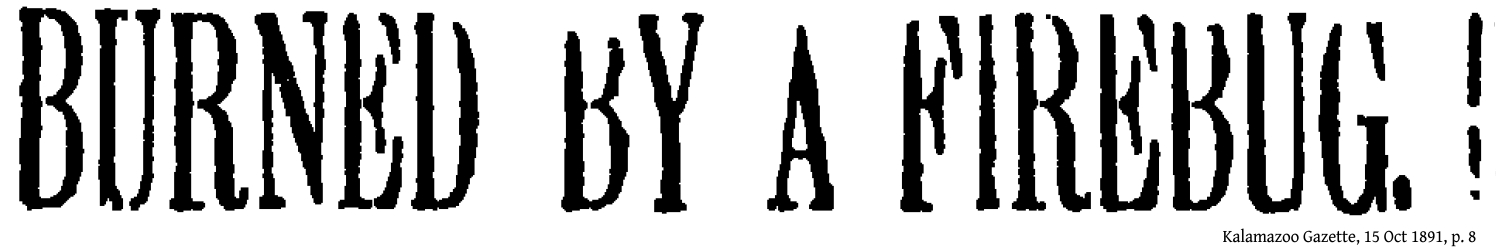

On October 15, 1891 this Kalamazoo Gazette headline screamed:

It was one of the town’s “most exciting and sensational scenes in its history” and Washington, Indiana detectives were investigating the recent courthouse fire. After arresting four persons allegedly associated with the “incendiarism”, one suspect, Samuel Harbine, confessed and implicated others. Among those implicated was none other than Daviess County’s auditor, James C. Lavelle. Lavellle’s brother Michael and two prominent county residents were also implicated.

Harbine admitted auditor Lavelle had hired him to burn the courthouse for a sum of $500, although to date only $5 had been received. As the story unfolded, another accomplice, Basil Ledgerwood, was anxious to turn state’s evidence in exchange for admitting his remuneration was a house and lot. Lavelle had been the county auditor for almost eight years and had earned

the trust of county residents. With evidence mounting against him, the county was forced to hire experts to review his accounts (presumably, those which hadn’t been destroyed).

The entire episode had turned the town upside down – almost suspending regular business – as everyone was “discussing the arrest of the conspirators” who had used coal oil to fuel the fire’s destruction which “affected the titles of nearly every landowner in Daviess county.” Understandably, “threats of mob violence [were] freely made.”11

Justice Delayed?

If a trial was in session and a courthouse fire mysteriously occurred in the middle of the night, chances are someone was trying to destroy evidence to prevent justice from being carried out. Sometimes fires were set to carry out vigilante justice.

In 1930 a lynch mob killed George Hughes, a Negro man accused of attacking a white woman in Sherman (Grayson County), Texas. Hughes was then locked in a vault in the courthouse basement as attempts at mob violence were averted, the third attempt thwarted by Texas Rangers and local law enforcement after plans to use dynamite were uncovered. Undeterred,

the mob resisted and set the courthouse on fire. So many fires, so many tragic stories.

Of course, those irretrievable records aren’t just a source of headaches and disappointment for genealogists today. At the time of these unfortunate incidents, hundreds of court cases and various legal actions were left hanging or unresolved in both the near and longer-term due to destruction of records by fire or other disaster.

If you’re researching Civil War ancestors, you may have come across the term “burned counties”, often used in regards to Virginia research after many records were either destroyed during the Civil War or by courthouse fire. There are strategies for finding those records and the rest of this excerpted article provides some tips.

For more discussion on this issue and to read the entire article, complete with more examples and resources, purchase the issue here. FYI, this particular issue features a look back at all the United States censuses dating back from 1790-1940.

![]() Thanks for stopping by! For more stories like this one, consider subscribing to Digging History Magazine. Purchasing a subscription entitles you to subscriber benefits (20% off all services, including custom-designed family history charts) AND a chance to win your very own custom-designed family history chart! Details here (or click the ad below).

Thanks for stopping by! For more stories like this one, consider subscribing to Digging History Magazine. Purchasing a subscription entitles you to subscriber benefits (20% off all services, including custom-designed family history charts) AND a chance to win your very own custom-designed family history chart! Details here (or click the ad below).

Footnotes:

Crazy in Colorado: Wheels in Their Head

Here’s an excerpt from a “Mining Genealogical Gold” article in a Digging History Magazine issue featuring Colorado. The article in its entirety was originally published in the May-June 2019 issue and entitled, “Crazy in Colorado: Wheels in Their Head and (Other) Insane Stories:

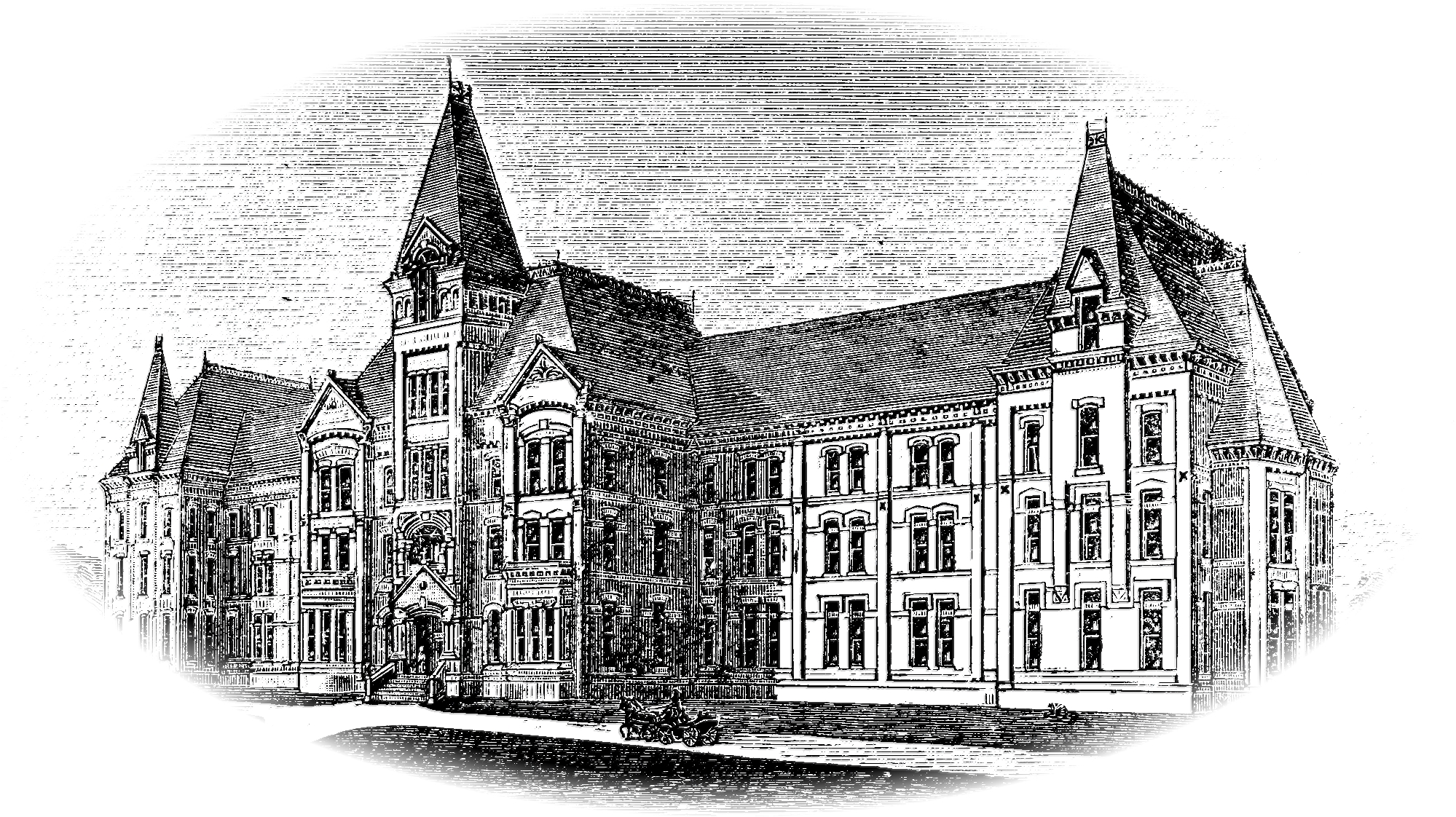

I came across some unique records several years ago while conducting research for a client. She wanted me to focus on an ancestor with a tragic story – she died at the Colorado State Insane Asylum in Pueblo in 1927. This institution has a long and storied history.

A series of small gold strikes precipitated the so-called Pike’s Peak Gold Rush as “Fifty-Niners” – Pike’s Peak or Bust! – flooded the region for three years before the rivers and streams played out. In 1879 silver was discovered high in the mountains at Leadville, founded in 1877 and known as “Cloud City” at an elevation well over 10,000 feet. On February 8, 1879 the Colorado State Legislature enacted legislation to establish the young state’s first public hospital for the insane.

At any given time during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries there were plenty of people deemed insane in Colorado. Many were confined to the state asylum in Pueblo, and if the asylum was full, in local jails. Local authorities, no doubt, preferred to shuffle their crazies off to the state facility in Pueblo.

Early asylum records indicate quite a few Leadville residents ended up in Pueblo for one reason or another. Was it the altitude? Was there something in the water (or the whiskey)? Was it the isolation of the miner toiling day in and day out, hoping for the next big strike, only to come up empty-handed again (and again)?

“Wheels in Their Heads”

That was the Rocky Mountain News headline on September 8, 1893 as one man after another was adjudged insane in a Denver court. Alfred B. Clark, standing trial for lunacy, appeared fully sensible as most – until someone brought up the subjects of electricity and religion. “Then he became wild.”

Another, John Gunnison, had been accused of killing another man and was now in constant fear of someone attempting to murder him. Albert Anderson’s “bump of locality” (a phrenological term) had been injured, so much so he believed himself to be somewhere near the Columbian exposition (being held in Chicago that year). Another had received a bump on his noggin and insane ever since.

Overcrowding at the Pueblo asylum was a constant problem. The same could be said for county hospitals often forced to take in the insane. In November 1896 the Rocky Mountain News was decrying the level of care for the county’s “wheely citizens”. After all, the county hospital had never been intended to house this unfortunate group of citizens numbering around thirty.

One reporter “took in the whole works” courtesy of a member of the medical staff. The insane population ranged from the “white-haired old lady who is simply ‘off’ at times, to the wild, destructive maniac in whose diseased brain is moulded only by a desire to kick, bite, glare and make a ‘large noise.’” The second floor was home to a “miscellaneous assortment of the daft, all women.” None were really much trouble at all, but someone had to keep an eye on them at all times.

In 1894 the county hospital had its hands full with one unfortunate inmate, Harry Noble Fairchild, a former Colorado Assistant Secretary of State. Again, the state facility was full. Fairchild put on quite a display at his hearing, as the room was filled with leading politicians of the city and state:

He was brought from the county hospital in charge of guards, his hands in muffs and his wild cries startling all who were in the building. So violent was the form of the mania that he was not permitted to take the stand, and it was with greatest difficulty that he was restrained from doing injury to the spectators. “Harry Noble Fairchild!” he screamed, “The first god of the earth.” . . . Amid the turmoil created by his cries, the people sat quietly, and no remark of the insane man, although many were witty and some grotesque, caused a smile on the face of anyone. . . In maudlin tones Fairchild fought again the battles of the war, which he entered as a boy. . . Again he was behind the walls of Andersonville, and lived over the days and months of anguish, hunger and cruelty [his name doesn’t appear in Andersonville prison records]. . . He never ceased speaking for an instant, and most of his remarks were addressed to the court. “Judge! Judge!” he yelled, addressing the court, “both your legs are off, and your heart’s been hanging out for some time.” Airships, canary birds, campaigns and other things and objects were hopelessly tangled in his brain. . . The doctors testified that the disorder was, under certain conditions, curable. The jurors saw the strange actions of the man, and these were far more convincing than the testimony of experts. They were absent only a few moments, and amid a hush Clerk Reitler read the verdict, that “Harry Noble Fairchild is so disordered in his mind as to be dangerous to himself and to others, and as to render him incapable of managing his own affairs.”

What became of Harry Fairchild is unknown. Perhaps he died in Pueblo. In 1992 skeletal remains of approximately 130 people were uncovered near the site of the original grounds, leading anthropologists to posit them buried there between 1879 and 1899. Inmates would have likely been buried in unmarked graves.

I first encountered this database while researching for a client who wanted to know more about her great-grandmother who had been committed to the Pueblo asylum in the early 1900s. Her condition appeared to have been related to uncontrolled epileptic seizures, once thought to have been caused by evil spirits.

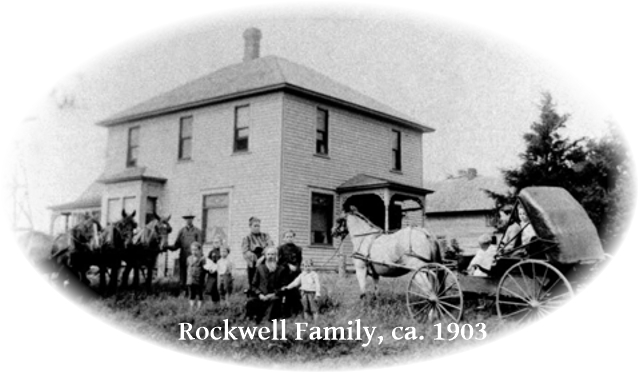

Martha Lorena Rockwell married German immigrant Folkert (Frank) Bokelman in 1908 in Cass County, Nebraska. Lorena was the daughter of Abraham and Mary Ann Rockwell, one of their ten children, growing up on a farm near Weeping Water, Nebraska (Cass County). Lorena was 17 and Frank was 28. Six children later, Lorena filed for divorce in April of 1920. Sometime in 1920, records indicate Lorena also spent time in the Lincoln State Hospital.

Presumably, the divorce petition was dropped at some point because by 1922 Lorena had been committed to the Woodcroft Hospital in Pueblo, Colorado. According to the Wray Rattler, Wray County (Colorado) was footing the bill for her board and care.

Frank had moved his family to Sidney, Nebraska (although likely lived in Yuma, Colorado at some point it appears) and on June 18, 1922 signed papers committing Lorena to Woodcroft. She was also pregnant with yet another child. Colorado State Hospital notes indicate Lorena was admitted from Woodcroft on November 6, 1922 in the last stages of pregnancy. Her baby was born in Ward 4 soon afterwards.

On June 18, 1923 Frank arrived to take Lorena and the baby home to Sidney. He signed a release form, “contrary to the advice of the Superintendent”. Should his wife require more care she would be placed in a Nebraska facility. Although it’s unclear as to why Lorena went to the Colorado facility in the first place (being a native Nebraskan), she returned to Pueblo on August 24, 1923 because the Nebraska institute refused to care for her. Frank brought her home to Sidney and she ran away. Clearly, he could not care for her.

Even though Lorena was committed once again to the Pueblo hospital was she really insane? That may not have been the case, at least in the clinical sense. Hospital records point to her history of grand mal seizures. Newspaper accounts also bear out those facts, although not implicitly stated.

On February 21, 1914 the Omaha Daily Bee reported the following:

Mrs. Frank Bokelman was seriously scalded Tuesday. She fell while carrying a teakettle filled with hot water. The hot water scalded her body from the neck down.12

Three years later The Plattsmouth Journal reported another accident:

Mrs. Frank Bokelman was badly burned on the left arm and right hand Monday morning when she fell on the cook stove while preparing the morning meal.13

How frequent were the seizures? While in the Colorado State Hospital it was noted Lorena was well-oriented, clear and a good worker between seizures. Otherwise, when the seizures were active, she might seize three or four times a day (grand mal), followed by a respite of one or two weeks. Through the years her pregnancies appear to have increased the frequency and severity of the seizures. No wonder she was seeking a divorce!

Lorena Bokelman died on June 18, 1927 of tuberculosis with the contributing condition of “psychosis with epilepsy”. By this time her children had been placed in other homes, adopted by strangers. Shortly after Lorena’s death, Frank died as well, although exactly where or how is unclear. While researching Lorena and Frank Bokelman for a client and looking for records of the Pueblo hospital, I came across this somewhat obscure asylum database.

While I didn’t find anything specifically about Lorena Bokelman in the asylum database, glancing through this voluminous set of records revealed some fascinating information which would help me understand more about people who, like Lorena, had no other medical recourse than to be committed to an asylum. This particular database didn’t contain hospital records, but snippets compiled from census records and newspapers. Not surprisingly, the newspaper clippings provided the most enlightening information (yet another reason why newspaper research is essential to genealogy!). For more information regarding this unique database (link provided in the magazine article), see the link in the opening paragraph to purchase this issue.

Thanks for stopping by! For more stories like this one, consider subscribing to Digging History Magazine. Purchasing a subscription entitles you to subscriber benefits (20% off all services, including custom-designed family history charts) AND a chance to win your very own custom-designed family history chart! Details here (or click the ad below).

Thanks for stopping by! For more stories like this one, consider subscribing to Digging History Magazine. Purchasing a subscription entitles you to subscriber benefits (20% off all services, including custom-designed family history charts) AND a chance to win your very own custom-designed family history chart! Details here (or click the ad below).

Thanks for stopping by! For more stories like this one, consider subscribing to Digging History Magazine. Purchasing a subscription entitles you to subscriber benefits (20% off all services, including custom-designed family history charts) AND a chance to win your very own custom-designed family history chart! Details here (or click the ad below).

Footnotes:

Legal, Nefarious and Quirky Name Changes: Tracking Down Ancestor Aliases

“a.k.a.”, although perhaps not as ubiquitous as “LOL” or “OMG” in our increasingly emoji and acronym-driven world, is commonly used today. While there exists more than one interpretation of the well-known acronym, the most common usage, “also known as”, is a legal one in terms of identifying either a legal or, in the case of one (or more) of our elusive ancestors, a nefarious name change.

As an adverb the term “alias” means “otherwise”, “also known as” or “also called”. As a noun the term might range in meaning for any number of reasons – “assumed name”, “nom de plume”, “pen name”, “nickname”, “stage name” and so on. By 1935 the acronym had become a common legal term. However, for years the term “alias” was more commonly used when noting someone might otherwise be known by another name.

Anyone who has spent time researching ancestors – especially the “disappearing” kind – has mulled over whether their kin had, for some reason or another, changed their name. Human nature being what it is, one of the first questions we often ask ourselves is “were they running from the law?”. Of course, that was sometimes the case, and finding them is exponentially more difficult because they obviously didn’t want to be found.

There are any number of reasons why someone might have changed their name, although not always via proper legal channels:

● Immigrants with difficult to spell or pronounce names

● Political reasons, such as immigrants dealing with prejudice and social isolation in wartime

● Running from the law, or leaving behind an otherwise unfortunate past

● Adoptee or foster child changing to surname of legal guardian

● Slaves changing their name to distance themselves from a painful past

● Victims of abuse

● Joining a religious order (monastery or convent)

● Celebrities, or other famous people, who change their otherwise common name

Probably the hardest to track down, of course, is the nefarious use of an alias (or aliases) involving a criminal act.

On the Lam

Obviously, there’s a reason the most difficult name change to trace is the felonious/nefarious kind since the individual likely wouldn’t have pursued any type of legal instrument. In the case of one client’s ancestor, he was born John Adam Boozer, the son of George Henry and Mary Jane (Wilson) Boozer, on April 24, 1852 in Newberry County, South Carolina. John appears to have been their first child and in 1860 and 1870 was enumerated in their household.

While family historians aren’t certain as to his whereabouts for the next five years, evidence suggests he was a drifter and may have been fleeing the law. I haven’t found any specific family story which points to the crime, but around the time he may have run into trouble with the law I found this news item in 1872:

John Boozer, alias Charley Mason, Watson and Wilson, and hailing from Newberry, suspected of horse-stealing, was arrested in White County, Ga., On the 29th ultimo, and committed to jail in Abbeville County.14

Horse-thieving was quite a serious crime at the time. If this is the same John Boozer as my client’s second great grandfather, it’s certainly possible he escaped from jail and headed west to begin a new life. By all accounts, John ended up in Clark County, Arkansas working for Hezekiah “Ki” Cash. In January 1874 he married Mary Amanda McCollum, Hezekiah’s seventeen year-old niece.

It’s entirely possible Mary Amanda was living with her uncle at the time, since her father, John Webster McCollum, died in 1862 while serving in the Confederate Army. Her mother, Alley Banks (Cash) McCollum, died after the 1870 census, perhaps around 1871.

Should the news clipping refer to my client’s ancestor John Boozer, he had already become adept at evading the law by utilizing various aliases. However, if this is one and the same person, he was not using an alias at the time of his marriage.

Exactly when it happened is unclear, but one fateful day John Adam Boozer took the name of John Adam Cash, packed his family off to Texas, never to be heard from again. It was the day his past caught up with him, compelling him to choose his mother-in-law’s maiden name as his new surname. As the family story goes:

They had been married a few short months when a stranger, presumed to be a lawman came to Caddo valley looking for a man who fit John Boozer’s description. John and Mary left the community one night, taking with them only what household items that could be loaded into a wagon. They left chickens, hogs, cattle, a garden and a crop in the field. No one in the family ever heard from them again. Some of the family members thought that John was a wanted man for some crime he had committed before moving into the community and that the man who came asking questions was a law officer.15

After the mid-1870s there are no more references to John Adam Boozer. However, there is an 1880 census record for John A. Cash, his wife Mary A. and their two children in Goliad County, Texas. According to the 1880 Non-Population Agricultural Schedule, John Cash owned 100 acres of land. As one researcher remarked, “not bad, for someone described as a ‘drifter’!”16

These theories seem plausible based on solid deduction of known facts and family lore passed down through the years. However, without these theories carefully pieced together, it would be difficult for anyone to have picked up on the reasons Ancestry.com shows John Boozer in South Carolina, while in 1880 he (known then as John A. Cash) is living prosperously in Goliad County, Texas.

I’m not a big fan of so-called “family lore” because I’ve often found it to be nowhere near the truth. Although I’m always up for the challenge, it’s difficult to prove when someone asks me to prove so-and-so, rumored to be related to them, is a direct ancestor. In the case of John Adam Boozer, without this particular piece of the puzzle (family lore) it would be difficult for a researcher to take John A. Cash any farther back than the 1880 census. The worst case scenario would involve a fruitless search for someone surnamed Cash born in South Carolina around 1851. It would have led a researcher straight down a rabbit hole of unsubstantiated (and wasteful) research.

In this case family lore is, I believe, correct even if some facts are assumed. The great thing about John Adam Boozer, a.k.a. John Adam Cash, is his birth family of Swiss heritage. Several books have been written about this family and its illustrious history. In fact, the original name was variously Booser, Busser or Buser, changed to Boozer upon arrival in South Carolina. Why the family used Boozer with a “z” has yet to be uncovered in my research, however.

Other than family stories, what might be alternative strategies to find an ancestor suspected of a felonious past? It might take awhile to track down anything at all useful, but newspaper research would be one avenue, especially if your ancestor was a known felon who often used aliases. In that case, record all the known aliases reported in newspaper accounts – and good luck!

This is an excerpt from an extensive article published in the March-April 2020 issue of Digging History Magazine. The remainder of the article provides a number of examples of aliases and name changes, some legal, some nefarious and some for one quirky reason or another. These may provide some inspiration for finding your difficult-to-locate ancestors. Purchase the issue here.

Thanks for stopping by! For more stories like this one, consider subscribing to Digging History Magazine. Purchasing a subscription entitles you to subscriber benefits (20% off all services, including custom-designed family history charts) AND a chance to win your very own custom-designed family history chart! Details here (or click the ad below). Questions? Contact me: [email protected].

Thanks for stopping by! For more stories like this one, consider subscribing to Digging History Magazine. Purchasing a subscription entitles you to subscriber benefits (20% off all services, including custom-designed family history charts) AND a chance to win your very own custom-designed family history chart! Details here (or click the ad below). Questions? Contact me: [email protected].

Footnotes:

Sarah Connelly, I Feel Your Pain (Adventures in Research: War of 1812 Pension Records)

Here’s a look back at a 2019 article published in Digging History Magazine, a personal one, from an issue which featured the War of 1812:

I hadn’t looked at this particular line for some time, but after someone saw this particular surname on my family’s pedigree chart (with an interesting story of someone with the same surname) I decided to take another look. I suspect I set it aside some time ago because, at least circumstantially, it appeared I had the correct parents for my third great grandmother Mary Ann Connelly, yet I couldn’t locate absolute proof.

So, a little more digging was in order. Curiously, I had several hints for Mary Ann’s mother but not her father, Henry Connelly. After realizing I had mistakenly input an incorrect birth location — dang auto-correct(!) — I registered several hints for him. After clicking on the new hints I found previously posted bits and pieces of War of 1812 Pension and Bounty Land Warrant application files. These were actually part of an extensive package (41 pages) of what turned out to be a “Eureka!” moment for researching this family line.

Henry and Sarah (Phillips) Connelly married on August 20, 1810 in Clay County, Kentucky, this according to affidavit after affidavit from Sarah Connelly following passage of the War of 1812 Act of February 14, 1871. In part:

The act of February 14, 1871, granted pensions to survivors of the war of 1812, who served not less than sixty days, and to their widows who were married prior to the treaty of peace.17

Sarah began her quest not long after the bill’s passage, engaging the services of attorney William F. Terhume in April.

Henry, born circa 1787, enlisted in the Kentucky militia on November 10, 1814 and was honorably discharged on May 10, 1815. Among the qualifications for a widow’s pension was to prove you and your now-deceased spouse had married and co-habitated prior to the Battle of New Orleans (January 8, 1815).

In 1871 Sarah was eighty years old, and while she would eventually have problems remembering the company Henry had served with and a few other details, she remembered the date of her marriage and the ceremony performed by Reverend Spencer Adams, a Baptist preacher. Clay County was established in December 1806, carved from parts of Madison, Floyd and Knox counties. Whether her marriage in the early days of Clay County contributed to her inability to locate proof is unclear, as Sarah discovered there was no official or public record of the marriage. The marriage had been witnessed by four long-deceased individuals, and Henry had passed away in 1859 (dropsy according to the 1860 Mortality Schedule).

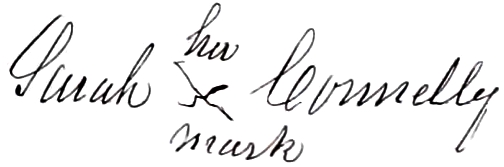

Mr. Terhume began the process after an agreement for payment of services to be rendered ($25.00) was executed on April 5, 1871. By her mark Sarah agreed to those conditions:

Terhume wrote the first letter six days later, addressed to the Commissioner of Pensions:

Terhume wrote the first letter six days later, addressed to the Commissioner of Pensions:

I enclose a pension claim under the late act of Congress for a widow of a soldier who served in the war of 1812.

I trust you will find it in sufficient form. Permit me to suggest that these claims should receive early attention for the reason that the applicants are quite aged and may not live many of them to enjoy the bounty of the government.18

Terhume also inquired about instructions, and if any existed, requested copies. Ever so promptly (not!) the government sent a circular dated September 16, 1871. In the following order the government required proof:

● A certified copy of a church or other public record.

● An affidavit of the officiating clergyman or magistrate.

● The testimony of two or more eyewitnesses of the ceremony.

● The testimony of two or more witnesses who know the parties to have lived together as husband and wife from the date of their alleged marriage, the witnesses stating the period during which they knew them thus to cohabit.

● Before any of the lower classes of evidence can be accepted, it must be shown by competent testimony that none higher can be obtained.19

As previously noted the first three forms of proof were out of the question — three strikes, Sarah is out?

Included in the first correspondence, executed on the same day as the fee agreement, was an extensive affidavit witnessed and averred to by Sarah’s son-in-law William H. Pugh (my third great grandfather) and his brother George Washington Pugh who had married a woman also surnamed Connelly (she also being a Mary, and Mary Ann’s cousin I believe).

In this affidavit significant information was provided as evidence Henry Connelly had served during the War of 1812. Included with information provided was a proclamation of total allegiance to the United States. Given that the Civil War was still a touchy subject, perhaps Mr. Terhume thought it best to include this statement:

… and further that at no time during the late Rebellion against the authority of the United States did I [Sarah] adhere to the enemies of the United States government neither gave them aid or comfort, and I solemnly swear to support the Constitution of the United States.20

It was also noted that Sarah had already received a land warrant from the government. (Eventually the government would indeed produce its own evidence, a Widow’s Claim for Bounty Land originally authorized on August 31, 1864.)

Her son-in-law and his brother signed similar statements, both pledging fealty to the federal government. Based on the government’s September 1871 response the original statements had been insufficient to move forward with Sarah’s claim. The matter was “suspended” in January 1872 until proof of cohabitation could be provided.

Meanwhile, Terhume had been pursuing, with diligence, means of proof, yet without success. He continued to try and locate someone in Kentucky who would remember, but by September 25, 1872 had received no response. Terhume had found someone willing to keep digging in Kentucky but would likely have no further proof until at least January of 1873.

Sarah was in a bind as far as the matter of marriage proof was concerned. So, what to do when you’re in a pinch? Call on your in-laws, of course!

It’s a bit curious to me the family didn’t think of this before, but on January 13, 1873 an affidavit was signed by two of Sarah’s in-laws. One was Mary Pugh, George’s wife and the other was Frances Pugh, my other fourth great-grandmother. I like to call her “Feisty Frances”.

Frances Townsend Pugh was born in Virginia on June 26, 1794. A few months before her sixteenth birthday she married William Pugh. Their marriage produced twenty-one children, thirteen of whom lived to adulthood. William (born in 1787) died in 1869 and Frances, according to Vernon County, Wisconsin history, was “well preserved and enjoyed good health.”21

At the age of ninety she was still able to take walks and one day came upon a rattlesnake with seven rattles. The snake slithered away but Frances grabbed a stick, “hunted the venomous reptile out from his hiding place and killed it; this took more courage than most of her children and grandchildren would have possessed.”22

Frances was certain Henry and Sarah had been married prior to the Battle of New Orleans because she recalled the birth of one of her own children the same year and day of the month as a child Sarah had delivered. While Mary Pugh (George’s wife) agreed about the marriage, Frances’ statement was the strongest.

Their statements helped settle the matter it appears, because on January 23, 1873 the government issued a “Brief of Claim for a Widow’s Pension” for Sarah Connelly. The brief referenced a report from the Bounty Land Division, along with previous statements by George and William Pugh and Frances and Mary Pugh.

Sarah Phillips Connelly was granted a widow’s pension of eight dollars per month. Sarah died on September 6, 1874 at the age of eighty-three. I found Sarah’s story compelling, as told through the back and forth correspondence, wrangling with the federal government. Obviously, her memory was failing as she struggled to remember certain facts, at one time stating Henry was a Private and Express Rider, and in another statement he was a Lieutenant (big difference!). I also felt her pain. Why is that?

I felt her pain and more than likely her frustration. It made me think of what we as genealogists go through to find the ABSOLUTE proof required to prove so-and-so is our ancestor. In regards to the absolute proof I had been looking for, one of the documents listed William and Sarah’s children — Mary Ann among them. She lived in an age where there was no such thing as “instant” anything in terms of vital information. Sarah, her attorney and her family persisted, however, until they were successful. And, so must we all. As I always like to say — KEEP DIGGING!

Thanks for stopping by! For more stories like this one, consider subscribing to Digging History Magazine. Purchasing a subscription entitles you to subscriber benefits (20% off all services, including custom-designed family history charts) AND a chance to win your very own custom-designed family history chart! Details here (or click the ad below).

Thanks for stopping by! For more stories like this one, consider subscribing to Digging History Magazine. Purchasing a subscription entitles you to subscriber benefits (20% off all services, including custom-designed family history charts) AND a chance to win your very own custom-designed family history chart! Details here (or click the ad below).

Footnotes:

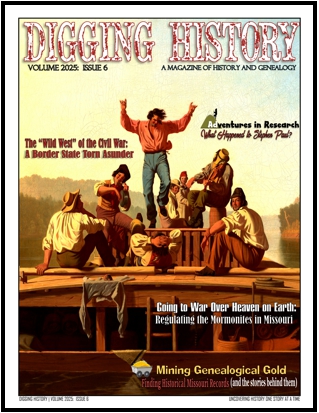

The Civil War in Missouri: A Border State Torn Asunder

The latest issue of Digging History Magazine is out and available by single issue purchase or subscription (three budget-minded options). This issue, the final issue of 2025, features the “Show Me State” of Missouri, its history and how to find the best historical and genealogical records. Among the featured articles is an extensive one, entitled “The ‘Wild West’ of the Civil War: A Border State Torn Asunder”. Here is a short excerpt from the article, created using AI Text to Speech technology.

Other articles featured in this issue include:

Other articles featured in this issue include:

- Mining Genealogical Gold: Finding Historical Missouri Records (and the stories behind them)

- Going to War Over Heaven on Earth: Regulating the Mormonites in Missouri

- Essential Tools for the Successful Family History Researcher

- Adventures in Research: What Happened to Stephen Paul?

This issue features over 100 pages of Missouri history, as well as tips for finding the best records (many of them absolutely free!) — no ads, just stories and great tips! Purchase it by clicking here.

To learn more about the digital magazine and the services offered by Digging History, see this special promotional page which provides information about the chance to win a custom-designed family history chart: https://digging-history.com/dhmpromo/