Wrapping up 2018 – Rolling into 2019

Digging History Magazine was launched in January 2018 and twelve issues were published last year. I decided to publish a free article index for anyone interested in taking a peek (all at once) at a list/synopsis of all articles. All 2018 issues are available for sale in the Magazine Store, some at reduced prices, along with the free article index.

The first issue of 2019 is also available (January-February). This year the magazine will be published bi-monthly, but still packed with articles focused on history and genealogy, This issue features articles which take a look back at events of 100 years ago. This year the magazine will feature several articles looking back at 1919, a volatile and momentous year in American history. February is Black History Month and this issue features a guest article written by the descendant of a freed slave whose legacy still matters today. Two articles on manumission and free people of color owning slaves are of interest both historically and genealogically. Feature articles include:

- The Boston Molasses Flood of 1919: could it have been an omen for the volatile year ahead for America?

- Hell for Rent: A Nation Goes Dry: On January 16, 1919 Nebraska became the 36th state to ratify the 18th Amendment to the United States Consitition. One year later, King Alcohol would be dead – or would he? A bit of history on the temperance movement, including the outrageous tactics of one well-known “saloon smasher” who made a name for herself in the early twentieth century.

- Edith, Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner: Theodore Roosevelt unexpectedly became President of the United States in 1901, following the assassination attempt and death of President William McKinley. T.R. wasn’t too far into his presidency before a long-forgotten incident occurred. It seemed innocent enough at the time, but would generate a firestorm of criticism, especially from Southern Democrats who already didn’t trust him.

- The Life of James Clemens – From Slavery to Unspoken Greatness: This issue features a guest submission from one of the descendants of James Clemens, a freed slave who went on to participate in the Underground Railroad movement. His story still matters even today.

- Manumission: Free at Last (or perhaps not) – This extensive article explores the subject of manumission of slaves. A bit of history and stories of controversial manumissions (they all seemed to be controversial). Mathews v. Springer was a precedent-setting case in post-Civil War Mississippi.

- Free to Enslave? is a look at a few incidences of free persons of color owning slaves. One of the featured characters, William “April” Ellison, was at one time the largest slave owner in South Carolina, and a cruel one at that. Milly Pierce’s story is a bit more hopeful, but it’s a piece of African American history that sometimes gets overlooked.

- Jaybird-Woodpecker War: This long-running feud in Fort Bend County, Texas had nothing to do with birds of any feather – rather, it was an all-out race war which stretched into the 1950s.

- What’s in a Name? Sometimes you just have to do a little digging when something piques your curiosity. Such was the case with an unusual name given (Seawillow) to a girl born in the middle of a torrential rain storm in 1855.

- OK: Everything Has a History – even the word we use millions of times a day: O.K. It was part of a silly nineteenth century fad, but yet endured.

- America Waldo Bogle: It wasn’t easy being a person of color in Oregon Territory. America Waldo Bogle’s story is a story of perservering and succeeding despite racial tensions.

- Preview issue here

Sarah E. Goode

She was born Sarah Jacobs to parents Oliver and Harriet Jacobs of Toledo, Ohio in approximately 1855. The family was enumerated in the 1860 Census in Toledo and listed as being of the Mulatto race, and Oliver was a carpenter. By 1870 the family had migrated to Chicago where Oliver was still employed as a carpenter. Sarah was fifteen years old that year and by the 1880 census she had married Archibald Goode, he employed as a stair builder.

She was born Sarah Jacobs to parents Oliver and Harriet Jacobs of Toledo, Ohio in approximately 1855. The family was enumerated in the 1860 Census in Toledo and listed as being of the Mulatto race, and Oliver was a carpenter. By 1870 the family had migrated to Chicago where Oliver was still employed as a carpenter. Sarah was fifteen years old that year and by the 1880 census she had married Archibald Goode, he employed as a stair builder.

This article is no longer available for free on this site. It has been enhanced with footnotes and sources and is available for purchase in the magazine store as an Individual Article.

New Year – New Look

Happy New Year! 2019 is off to a good start here at Digging History with a redesigned web site. It looks a LOT different than the previous one.

The new look is crisper with a new logo which highlights our genealogical research services and charts AND Digging History Magazine. Last year the magazine had its own web site, but experience has proven it will be better situated here now. No more going back and forth between the two sites. Makes sense, huh?

Click on Digging History Magazine and see what’s in the store:

- Subscriptions: Three levels to choose from to fit any budget; all subscriptions are automatically recurring until you tell me you want to stop. Pay-by-check is also available; see details on subscription page.

- Individual Issues (2018 had 12 month issues; beginning in 2019 issues are bi-monthly)

- Special Editions – Currently only one issue, Early American Faith (99 pages or articles, no ads, all focusing on early American faith)

- Individual Articles: From time-to-time some articles will be available for individual purchase rather than part of an issue. Individual article purchase available upon request by contacting me.

- Free Samples: Here you’ll find samples of previous issues (includes only selected pages from a particular issue) or a link to our YouTube preview site. Want an entire issue to try out? See the right side-bar to provide your email and subscribe.

- Purchase Month-to-Month Genealogical Research: A great way to budget research an hour at a time as a recurring subscription (until the project is finished or you would like to stop).

Many of the original blog articles remain, although some are pulled from time-to-time, enhanced and rewritten (adding new research, complete with footnotes and sources) and featured in an issue of the magazine. Most of the writing these days is for the magazine, although I will occasionally post a thought or two, or advertise a special offer (research, charts, magazine) as a blog article.

You might ask, “Is it worth it to purchase a subscription?” That depends — are you a history-lover? Do you enjoy reading about unique historical events or characters? Are you a genealogist or family history researcher (or want to be one)? If you can answer “yes” to any of those questions, then I would say YES (of course I would say that)! Most issues these days are running between 65-80 pages — no ads, just lots of history and articles focused on genealogical research. You’ll find the genealogical research articles aren’t “dry” — they are packed with history as well. There are other publications that do “dry” … I don’t do “dry” 🙂

Again, if you’d like to view an entire issue go to the right side-bar and provide your email address to subscribe. Already a subscriber to the web site? Go to the Individual Issue page and check out the issues available. Just contact me and indicate the issue you want and I’ll send it to you for FREE just to see what it’s all about.

Again, if you’d like to view an entire issue go to the right side-bar and provide your email address to subscribe. Already a subscriber to the web site? Go to the Individual Issue page and check out the issues available. Just contact me and indicate the issue you want and I’ll send it to you for FREE just to see what it’s all about.

I’m always looking for interesting history to write about. Feel free to contact me with your ideas (or maybe you’d like to submit an article for publication?). I love history. If you’ve landed on this page, you probably do too. Let’s explore together . . . “Uncovering history one story at a time.”

Your friend and fellow history-lover,

Sharon Hall

Genealogically-Speaking: Precious Memories as Vital Records

Here at Digging History there are a couple of tag lines I like to use to convey the site’s purpose. One quote belongs to Rudyard Kipling:

“If history were taught in the form of stories, it would never be forgotten.”

The other is one I use for Digging History Magazine:

“Uncovering history one story at a time”

Both are reflective of what I think history should be — just stories. Think about it — there’s a story (history) behind everything. I honestly can’t think of anything that doesn’t have a history (a story), can you? I absolutely love digging around in old newspaper archives (one of my research specialties), and I write a fair amount of the stories published either in the blog or magazine straight out of those old newspaper accounts. I particularly enjoy reading newspaper articles from the Victorian era — there’s just nothing quite like old-fashioned Victorian prose.

Nothing, however, can compare to the stories we pass down to our family. Genealogists are always searching for meaningful records of an ancestor’s existence: census records, land records, military service and so on. Sometimes I think we are so focused on those (often elusive) records to the exclusion of missing the stories.

Today I drove my Mom and Dad over to my brother and sister-in-law’s house for a delicious Thanksgiving meal. Yesterday my Mom asked me to be sure and print a copy of a record she had come across years ago after my grandmother passed away. Today she had a story she wanted to tell around the Thanksgiving table.

Today I drove my Mom and Dad over to my brother and sister-in-law’s house for a delicious Thanksgiving meal. Yesterday my Mom asked me to be sure and print a copy of a record she had come across years ago after my grandmother passed away. Today she had a story she wanted to tell around the Thanksgiving table.

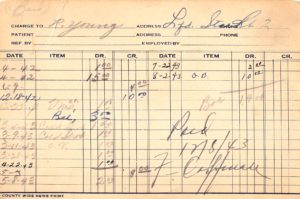

It’s not one of those highly-sought-after records, yet both genealogically and historical significant to me and my family — especially because of the stories my Mom told us today. The record may not look like anything genealogically significant (click to enlarge). In fact, at first glance one might wonder whatever in the world is it?

There is, in fact, quite a bit of history on this 4×6 card — especially if you know the stories behind it. This is a record of about a year and a half of visits to see Dr. Duke, a Littlefield, Texas physician who was my grandparents’ family doctor when they lived in the small farming community of Spade. At the top is my grandfather’s name. Although his name was “Roosevelt Young” (named in honor of Theodore Roosevelt, U.S. President in 1902), he signed his name “R. Young”. However, everyone called him “Bud” (also noted on the card) and his address was Littlefield Star Route 2.

The card is a record of visits and care for Bud’s family, several of which were for my Mom. My grandmother once said my Mom was “born sick”. She has experienced lung and breathing issues all of her life. The first entries on this card (4-42) for $1.00 and $15.00 were for a hospital stay when my Mom (seven years old) was unconscious for three days, her life literally hanging in the balance. Today she told us the tearfully emotional story of how her mother got on her knees and prayed and gave her daughter to the Lord’s care, after the doctor had told my grandparents he had done all he could do and it wasn’t up to him any longer. So, as my grandmother prayed, it truly was in God’s hands.

Mom told us today that while she was unconscious those three days she would sing “When the Saints Go Marching In” — the beginning of her “singing career” she now likes to say! On this Thanksgiving Day the record took on new meaning because we heard the poignant story behind it. It now means more than just a card with dates and dollar amounts — it’s a precious memory.

If you’re a genealogist, don’t toss these kind of records aside if you run across them. There may just be an interesting story, or, if you’re fortunate enough, a precious memory.

Digging History Magazine – November 2018

It’s November . . . a month of remembrance and thanksgiving. This month’s issue features quite a bit of World War I history:

- The War to End All Wars. World War I, also referred to as “The Great War”, was considered the first modern war, and until 1917 was a European war, albeit with increasingly dire and daunting implications for the United States. It would also be the first major conflict both prosecuted and propagandized at the direction of the nation’s Commander in Chief.

- Mining Genealogical Gold: Finding Records of the Great War (and the stories behind them). World War I, aka “The Great War” is historically considered the first modern war. Both historically and genealogically speaking, the records generated during this volatile time in American history are potentially a treasure trove of fascinating information. The best part? Lots of stories!

- Rolling Up Their Sleeves: World War I and the Road to Suffrage. After decades of campaigning for equality and the right to vote, women were ever so close to victory by the time the United States entered World War I in 1917. At war’s end even Woodrow Wilson was ready to acquiesce and push through the Constitution’s Nineteenth Amendment.

- PANDEMIC! On the Home Front: Blue as Huckleberries and Spitting Blood. Spring 1918. War headlines were intense enough by the spring of 1918 – the world was reeling from a war unlike any other in the history of the world. Soon – very soon – the world would be reeling from a different kind of war.

- Remembering Tombstone Tuesday. A look back at the very first article published at the original Digging History blog.

- Feisty Females: She Taught Amelia to Fly. When Amelia Earhart wanted to learn how to fly an airplane, the deal she struck with her parents required she be taught by a woman pilot. That pilot, Neta Snook, was a woman of many “firsts” – one of the first female aviators, she was the first woman accepted into a flying school, the first to run a commercial airfield and the first woman to run her own aviation business..

- Believe it or not . . . stranger things have happened: The Luckiest Fool in the World. World War I, the most deadly conflict in recorded history, was over and a bit more light-hearted era was just around the corner. Alvin “Shipwreck” Kelly made a name for himself as flag pole sitter — a one-of-a-kind daredevil.

- The Roaring Twenties: Wing-Walking. Another Roaring Twenties fad that actually led to amazing advancements in aviation technology. Ormer Locklear wasn’t just a daredevil — was a sky-devil.

- Way Beyond the Call of Duty: Milton Rubenfeld

- and more

Single issue purchase here ($3.99).

Affordable subscription options available here. Note that the 3-month, 6-month and one year subscriptions now come with a 30-day trial.

Digging History Magazine – October 2018

It’s October and everyone thinks Halloween . . . spooky stuff, you know? This month’s issue goes right along with that theme:

It’s October and everyone thinks Halloween . . . spooky stuff, you know? This month’s issue goes right along with that theme:

- American Poltergeist (and other strange goings-on). America has had its share of strange other-worldly phenomena. America’s first ghost made an appearance (or so they say) in 1800. Early colonists seeing flying ships . . . hallucinations or the real thing?

- Sister Amy’s Murder Factory. It’s a long and winding saga of what some call America’s first female serial killer. Was she crazy-crazy, crazy-manipulative, wicked-crazy or just plain crazy? You be the judge.

- Brown Mountain Lights: Appalachia’s Historical Mystery. A historical perspective from Kalen Martin-Gross, an Appalachian native.

- Genealogy Speaking: It’s Time to Rake the Leaves. It’s fall, it’s Family History Month, and what better time to take a closer look at the “leaves” on your Ancestry.com tree. You might be surprised at some records which may not be useful at all.

- Are you one of THOSE kind of people? If you’re a genealogist, you know THOSE kind of people I’m talking about — those who can’t pass up a cemetery stroll. What is with genealogists and dead people?

- Those Dang Saucers Appear Everywhere. You’ve heard about UFOs seen in the 1940s and 1950s. In July 1952 there were an unusually high number of sightings. What was that all about? Plus, an extensive look at the so-called Lubbock Lights.

- Hideous Insidious History. Quite often history inspires us. Unfortunately, sometimes it disgusts us. We don’t need to look away, but instead learn from it and pledge it will never happen again. A new column introduced this month.

- Grave Headlines. People (supposedly dead) coming up out of their coffins (and scaring the bejeezus out of funeral attendees!). No way (yes way!).

- Joseph Faubion: The Man Who Died Twice

- and more

Single issue purchase here ($3.99).

Affordable subscription options available here. Note that the 3-month, 6-month and one year subscriptions now come with a 30-day trial.

I Am Becoming . . . Therefore, I Must . . .

To be a writer, one must write. And so, on October 1, 2018, the 25th anniversary of becoming a self-employed entrepreneur, I write. It’s not what I started out doing 25 years ago, yet I am slowly, but surely, pursuing my dream of becoming a writer. Honing my God-given skills. As long as you’re alive and kicking you can pursue your dreams. Therefore, I must continue to write.

To be a writer, one must write. And so, on October 1, 2018, the 25th anniversary of becoming a self-employed entrepreneur, I write. It’s not what I started out doing 25 years ago, yet I am slowly, but surely, pursuing my dream of becoming a writer. Honing my God-given skills. As long as you’re alive and kicking you can pursue your dreams. Therefore, I must continue to write.

Will I write a book(s) someday? Perhaps so. I have amassed a portfolio of several hundred articles over the last few years, any number of which could be expanded into a book. I have also amassed more article ideas than I’ll ever have time to write. The great thing about history is you never run out of something to write. What happened two minutes ago is history.

I rather enjoy researching and writing my monthly publication, Digging History Magazine. I am also a genealogist, helping people discover their roots. I write their family stories as well. As I pointed out recently, researching and writing makes me a better genealogist.

It’s cathartic in a way, writing about long ago events, making a connection with the past. I am there. I try to take my readers there. Not all history is inspiring and uplifting, unfortunately. Parts of it – to our corporate chagrin – are outright disgusting. I wrote one of those kinds of stories for the October issue. History doesn’t always have a happy ending.

I am always exhilarated once I get a 60-70 page issue written, graphics designed, edited, finalized (yes, I do it all — it’s just me!), up for sale in the Magazine Store and off to subscribers to enjoy their monthly history fix. The magazine site, however, is not inexpensive to operate, and subscriptions and single issue purchases have been too few and far between this first year. I have been discouraged way more than I’ve been encouraged . . . yet, I will continue to write.

I make it a point to personally email each new subscriber to thank and tell them what a blessing they are to me – because they are, even if they’ve only purchased an $8 three-month subscription. I’ve experienced plenty of disappointment this year. Nevertheless, even those three-month subs inspire me – propel me — to keep writing.

This summer I made a new friend who purchased a three-month subscription, but just wanted to try it out. I cancelled the subscription so she wouldn’t be charged again three months later. However, something happened and she was mistakenly charged anyway (I’m still a newbie at this subscription administration thingie!). I emailed her right away to apologize and tell her I’d get her a refund if she still wanted to end her subscription. To my joyful surprise she emailed me back: “Please keep the subscription. I enjoy your magazine!” Was it perhaps kismet that she was mistakenly charged? I don’t know but those eight words were a much-needed pat on the back . . . keep writing.

I continue to write and publish and hope. I am a writer. Therefore, I will write . . . and write . . . and write.

If you are a subscriber, YOU ARE A BLESSING TO ME — make no mistake about it! If you enjoy the magazine, refer a friend — you’ll be a DOUBLE BLESSING TO ME! If you’re not a subscriber, I invite you to try it out. I promise you won’t be bored because history is more than a bunch of dates. We are uncovering history one story at a time. Rudyard Kipling said it best: “If history were taught in the form of stories, it would never be forgotten.”

3-month, 6-month and one-year subscriptions are available. Don’t like the magazine? Just tell me before the 30-day trial period is up and I’ll cancel (delete) your account and you won’t be charged further. Why would I take a chance on giving away an issue without the promise of a recurring subscription? My new friend told me, “Please keep the subscription. I enjoy your magazine!”.

Sharon Hall, PROUD Writer, Graphic Designer, Editor and Publisher of Digging History Magazine

Following is Easy . . .

September is about to wrap up and I’ve already given away one free issue of Digging History Magazine today. Would love to give away some more (today or any day)! Following is easy and you’ll get notification of occasional blog posts and special offers. The current special offer ends on December 31, 2018 (more details below). Click the image below and it will take you directly to the Digging History Magazine web site; scroll to the bottom of the page; type your email and subscribe.

Whether you buy a subscription now or not, I’d love to share the magazine I’m so proud to write, publish and edit! Like I say, it’s free — what have you got to lose?

Whether you buy a subscription now or not, I’d love to share the magazine I’m so proud to write, publish and edit! Like I say, it’s free — what have you got to lose?

Best,

Sharon Hall, Publisher and Editor, Digging History Magazine

A New (and Improved) Way to Preview Digging History Magazine

Digging History Magazine is pleased to announce a new way to preview each month’s issue of the magazine. We now have a YouTube channel with previews of all issues published since January 2018. These previews will continue to be published on a monthly basis with links for purchase.

Digging History Magazine is pleased to announce a new way to preview each month’s issue of the magazine. We now have a YouTube channel with previews of all issues published since January 2018. These previews will continue to be published on a monthly basis with links for purchase.

Better than downloading a sample of just a few pages, you will be able to view snippets from all articles. A link to that month’s issue is provided in the video description (below the video). This month’s video preview can be viewed here. Please take the time to watch, “Like” and “Share” to help us spread the word.

In addition to purchasing individual copies ($2.99) of the magazine, a more economical way is to purchase a subscription. Each of the four budget-minded options is billed automatically until you tell me you want to cancel:

- Month-to-Month (a small savings over single issue purchase)

- Three-Month ($8)

- Six-Month ($16)

- One Year ($32)

Purchase subscriptions here with PayPal or a credit card. Have questions or need help with purchasing a subscription? Contact me at [email protected].

Here’s what people are saying about Digging History Magazine:

- I have recently subscribed to Sharon Hall’s Digging History Magazine after looking at several of the free articles. I’ve just finished reading the January issue. I’ve already learned a good bit and am having a great time doing it. The articles, which are extremely well written, are a joy. I especially appreciate the use of family stories to both engage the reader and at the same time emphasize and illustrate what to look for while researching. The combination of the author’s extensive knowledge, experience, love of stories and sense of humor are a winning mix. Each of the articles has been a great read. Time and money well spent. I strongly recommend that you take a look yourself. If you are interested in family history, I suspect you will be as hooked as I am. I look forward to digging into the rest of the issues. (And yes, I just had to add that last sentence.)

- Not only packed with good articles but many helpful hints you can use to research your own family history. Good Job Sharon!

- Fantastic issue on the Klondike! I have just dug into the articles, and it looks great. Excellent issue, as usual.

- I found the story about Stephen Paul in the April 2018 issue of Digging History Magazine to be very interesting. The writer intertwined her own voice with the research material in a way that is very compelling.

- I enjoyed this issue of Digging History, especially the story about Snowball, AK. I like that the unsolved mystery and the research into it raises new questions as well as giving possible answers to old ones. The author’s writing style really drew me in as a reader.

- What an issue! There is so much in this issue I did not know; like the predated Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence. Growing up in Virginia, and being an avid history buff, I know what a talented and intelligent man Thomas Jefferson was. . . I look forward each and every month for these magazines and thoroughly enjoy them cover to cover. Thank you, Sharon, for you continued dedication to supply us “history geeks” with such historically packed issues!

See what you’re missing? 🙂

Sharon Hall, Publisher and Editor, Digging History Magazine

3 to 25

3 to 25. Whatever does that mean? To me it means a milestone. Three weeks from today, October 1, marks the 25th anniversary of being a self-employed entrepreneur. In 1993 I started my first business, The Perfect Solution. Through the years I’ve had some fantastic clients (still do!) and I appreciate each and every one of them.

3 to 25. Whatever does that mean? To me it means a milestone. Three weeks from today, October 1, marks the 25th anniversary of being a self-employed entrepreneur. In 1993 I started my first business, The Perfect Solution. Through the years I’ve had some fantastic clients (still do!) and I appreciate each and every one of them.

I currently operate two more businesses: Digging History (providing ancestry research and custom family charts) and Digging History Magazine (a monthly digital publication focused on history and genealogy, available by single issue purchase or subscription).

How does one celebrate 25 years of being in business for oneself? What does one wish for? Business for Digging History and Digging History Magazine has been slow and sporadic this year. My initial goal for subscribers is 50 and I’m currently at 22. I’d like to boost that number up before year’s end to 50 (or more!). I love what I do — I LOVE history and want to share my passion with like-minded history nuts.

Subscriptions are easy to purchase at the Magazine Store. Here are the instructions:

- Select a subscription option.

- Checkout

- Scroll down and select a payment method and provide all requested information.

- Purchase and your subscription will begin and your first issue will be delivered post haste.

That’s it — EZ-PZ!

Want to “gift” a subscription to someone you know with a love of history. Contact me at [email protected] with your friend’s name and email address and I’ll send you an invoice (choose payment preference: credit card or PayPal) so they can begin receiving monthly issues courtesy of your generosity.

3 to 25 — care to make my day?

Blessings,

Sharon Hall, Publisher and Editor, Digging History Magazine