Wild West Wednesday: The Sweetwater Shootout

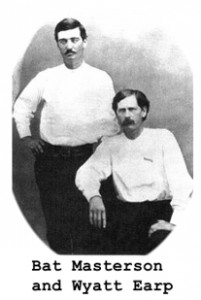

This event which took place on January 24, 1876 might have been just an obscure piece of American Western history if not for the fact that it involved twenty-three year-old William Barclay “Bat” Masterson. He was born on November 26 ,1853 and raised in Kansas. His first job at the age of seventeen was working a Santa Fe Railroad construction job. Bat was known to be handy with any gun he picked up, and when his employer failed to pay him he took a job as buffalo hunter.

This event which took place on January 24, 1876 might have been just an obscure piece of American Western history if not for the fact that it involved twenty-three year-old William Barclay “Bat” Masterson. He was born on November 26 ,1853 and raised in Kansas. His first job at the age of seventeen was working a Santa Fe Railroad construction job. Bat was known to be handy with any gun he picked up, and when his employer failed to pay him he took a job as buffalo hunter.

After an Indian fight, he went to work as a civilian scout for General Nelson Appleton Miles. His first assignment took him to a place in Texas called Sweetwater (first called “Hidetown” and later officially named Mobeetie). At the time, it was a buffalo hunting camp on Sweetwater Creek, the north fork of the Red River. Nearby was an United States Army outpost (later named Fort Elliott) where troops were assigned the duty of transforming Indian hunting grounds to an area suitable for settlement.

Masterson worked as a scout and teamster, hauling supplies in and out of northwest Indian territory (now Oklahoma). He also continued to work part-time as a buffalo hunter. The camp town of Sweetwater began to grow when businesses were opened – a restaurant, a boarding house, Chinese laundry, saloons and a dance hall. There was, however, no law enforcement. Charles Goodnight once said of Sweetwater (Mobeetie):

Masterson worked as a scout and teamster, hauling supplies in and out of northwest Indian territory (now Oklahoma). He also continued to work part-time as a buffalo hunter. The camp town of Sweetwater began to grow when businesses were opened – a restaurant, a boarding house, Chinese laundry, saloons and a dance hall. There was, however, no law enforcement. Charles Goodnight once said of Sweetwater (Mobeetie):

Mobeetie was patronized by outlaws, thieves, cut-throats, and buffalo hunters, with a large per cent of prostitutes. Taking it all, I think it was the hardest place I ever saw on the frontier except Cheyenne, Wyoming.

Masterson had arrived in Sweetwater in December of 1875 while hauling for the Army. On the night of January 24, 1876 he joined a poker game at the Lady Gay Saloon, playing with Harry Fleming, Jim Duffy and Corporal Melvin A. King. Also present that night were several of the dance hall girls who were enjoying a night off. One of the women, with a reputation as a prostitute as well, was named Mollie Brennan. She worked with several other women, including Kate Elder, a.k.a. “Big Nose Kate” and sometimes thought to be Mrs. John H. “Doc” Holliday (that’s a story for another article one of these days).

Melvin King had actually been born Anthony Cook in 1845. He enlisted in the 14th New York Heavy Artillery in October of 1863 and served until his regiment was captured on March 25, 1865. He was paroled on March 31 and by August he had been discharged from military service. On July 21, 1866 he enlisted in the 16th Infantry and was assigned to Reconstruction duty in Georgia. Considered a good soldier, he was somewhat of a troublemaker. Although court-martialed for “conduct prejudicial to good order and military discipline,” he was acquitted.

He was promoted to sergeant but his penchant for rowdiness earned him a reduction in rank, one year of hard labor and a pay forfeiture (although later reduced). After developing a drinking problem he was dishonorably discharged on August 24 ,1869 in Mobile, Alabama. From there he went to New Orleans and re-enlisted on October 28 in the 4th Cavalry as “Melvin A. King.” His regiment was transferred to the Texas frontier and later fought in the Red River War which began in 1874.

After his discharge in October of 1874, details are sketchy as to his whereabouts and activities. Some say he participated in raids on cow towns in the region. On April 29, 1875, however, he re-enlisted at Fort Richardson and rejoined his old company. He had been discharged the last time as a private but was promoted to corporal after re-enlistment and placed in charge of herding Indian ponies. In June he was re-assigned as Colonel Ranald Mackenzie’s orderly until October and then on to detached service in Sweetwater.

Eyewitnesses to the shootout said that King lost the poker game and left the Lady Gay rather disgruntled. After the game ended, Masterson chatted with Mollie and around midnight they and Charlie Norton (dance hall owner) walked over to the dance hall. Norton lit a lantern and Masterson and Mollie sat near the front door and continued talking. King had observed them entering the dance hall and knocked on the door.

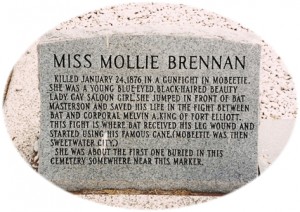

When Masterson rose to answer the knock, King, drunk and perhaps still angry over his poker loss, burst into the run with a revolver. The details offered by various witnesses are different as to what actually happened next. It is believed that Mollie jumped in front of Masterson who was shot in the abdomen. Then King fired again and mortally wounded Mollie, and after Mollie was shot Masterson fired and mortally wounded King.

A young boy was sent to inform the camp commander, and soldiers and a surgeon were dispatched to the scene. Mollie had already died but the two men were examined and prepared for transport back to the military hospital. King died the next morning. Mollie Brennan is thought to have been the first, or one of the first, people buried in the Mobeetie Cemetery. After recovering from his wounds, Masterson headed home to Wichita to recover and then on to Dodge City, Kansas where he worked as a lawman alongside Wyatt Earp.

It is still unclear as to why King was so angry that night. Was he merely angry over his loss at the poker table? Some believe Bat and Mollie were romantically involved and King was jealous (perhaps he had at one point been romantically linked to her). Legends and theories abound but King was known to be mean, especially when he had been drinking. In 1881, Masterson would downplay the shootout by saying, “I had a little difficulty with some soldiers down there, but never mind, I dislike to talk about it.” Nevertheless, the “Sweetwater Shootout” just might have been where the legend of Bat Masterson was born (or maybe it was the television series which ran from 1958-1961).

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Tombstone Tuesday: Hiram Hezekiah Leviticus Luttrell

Hiram Hezekiah Leviticus “Hez” Luttrell was born on July 19, 1867 in Lincoln County, Tennessee to parents Newton and Juliana Howard Luttrell. Newton had served in the Civil War in the 41st Tennessee Infantry and was captured on February 16,1862 at the Battle of Fort Donelson (Tennessee), a decisive victory for the Union.

Hiram Hezekiah Leviticus “Hez” Luttrell was born on July 19, 1867 in Lincoln County, Tennessee to parents Newton and Juliana Howard Luttrell. Newton had served in the Civil War in the 41st Tennessee Infantry and was captured on February 16,1862 at the Battle of Fort Donelson (Tennessee), a decisive victory for the Union.

Newton and his wife and seven children moved to Washington County, Arkansas in 1872. On January 1, 1890 Hezekiah married Mary Margaret “Mollie” Roberts Luttrell, the widow of his older brother James. James had married Mollie in 1879 and in 1882 was found dead on a ranch in Grayson County, Texas. Mollie returned to her family home in Arkansas and gave birth to their son Wiley Newton Luttrell.

Newton and his wife and seven children moved to Washington County, Arkansas in 1872. On January 1, 1890 Hezekiah married Mary Margaret “Mollie” Roberts Luttrell, the widow of his older brother James. James had married Mollie in 1879 and in 1882 was found dead on a ranch in Grayson County, Texas. Mollie returned to her family home in Arkansas and gave birth to their son Wiley Newton Luttrell.

Hezekiah and Mollie lived for a time in Arkansas but one family historian believes that by 1895 they had moved to Oklahoma, possibly Marshall County since it appears that is where Newton lived at the time of his death (which is unknown). It is believed that Hezekiah and Mollie had perhaps as many as six or seven children; however, only two survived to adulthood (in addition to Mollie and James’ son Wiley Newton). Sarah Alabama was born on October 6, 1896 and Elmer Forest on October 19, 1899, both presumably born in Marshall County, Oklahoma.

It is unclear when Hezekiah and Mollie left Oklahoma since no records can be found of their whereabouts between 1900 and 1910. They were enumerated in Wheeler County, Texas in the 1910 census as: Hes Luttrell, Ollie, Balma and Elmo (or translated, Hez, Mollie, Sarah “Bamma” and Elmer). Apparently, Hezekiah had received little schooling because according to the 1910 census he could neither read nor write. Wiley Newton, who went by Newt, lived next door to them with his wife, two young daughters, stepson and mother-in-law.

Elmer married LeLand Priscilla Fee in 1919 and Sarah married Jesse Godwin around 1920. Wiley Newton had moved back to Oklahoma in 1912 or 1913 and he died there on January 29, 1919, buried in the same Marshall County cemetery as his grandfather Newton. Hezekiah and Mollie remained in Wheeler County until their deaths. Mollie died on September 17, 1928 and was buried in the Mobeetie Cemetery. In 1930 Hezekiah was living alone and still farming.

Elmer married LeLand Priscilla Fee in 1919 and Sarah married Jesse Godwin around 1920. Wiley Newton had moved back to Oklahoma in 1912 or 1913 and he died there on January 29, 1919, buried in the same Marshall County cemetery as his grandfather Newton. Hezekiah and Mollie remained in Wheeler County until their deaths. Mollie died on September 17, 1928 and was buried in the Mobeetie Cemetery. In 1930 Hezekiah was living alone and still farming.

Sarah “Bamma” Luttrell Godwin passed away on April 16, 1934 and was also buried in the Mobeetie Cemetery. Presumably, Hezekiah continued to farm until his death in 1937. On the way to the mail box one day in January, he was tragically killed by a hit and run driver. He was buried next to Mollie in Mobeetie Cemetery.

Wheeler County

Here’s a little history bonus I discovered while researching today’s article. Wheeler County became the first county organized in the Texas Panhandle on April 12, 1879 and in 1880 Mobeetie (formerly a camp named Sweetwater) was designated as the county seat. Ranching drove the local economy until the early 1900’s when land began to be cultivated for farming. In 1910 there were over five thousand county residents and the county seat had been moved to Wheeler in 1907. Perhaps opening the county to farming was what drew Hezekiah to settle there. By 1930 cotton would become the most important crop, with over 93,000 acres planted.

In 1920 Texas sued the state of Oklahoma on the grounds that surveys conducted in 1858 and 1860 had incorrectly placed Oklahoma’s border, the 100th meridian, about one-half mile too far west. Of course, this would not just involve the border county of Wheeler, but the entire eastern Texas Panhandle strip (134 miles) which borders Oklahoma. The adjustment would require somewhere between 3,600 and 3,700 feet to make it true to the 100th meridian. According to Texas History Online, “One Oklahoma resident complained that she had not moved a foot in forty-five years but had lived in one territory, two states, and three counties.”

In 1927 the United States Supreme Court ordered Samuel S. Gannett to re-survey the meridian. It was an arduous task that took until 1929 to complete. Gannett worked at night, placing concrete markers at every two-thirds of a mile, to avoid the scorching heat of the day. In 1930 the Supreme Court was satisfied that Gannett’s survey was accurate, but apparently Oklahoma was not.

In 1931 the state of Oklahoma tried unsuccessfully to buy back the strip of land that had officially been taken away the year before. This border dispute was probably tame in comparison, however, to the other border dispute with Texas in 1931, the Red River Bridge War (read about it here), although Oklahoma claimed to have won that one.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

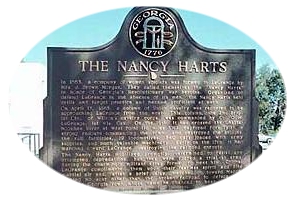

Military History Monday: The Nancy Harts

While their menfolk were off fighting the Union, many Southern women stepped up to defend their homes and families. One group of females in LaGrange, Georgia, however, officially banded together and formed an all-female militia. They called themselves the Nancy Harts in honor of Revolutionary War heroine and fellow Georgian Nancy Morgan Hart. In case you missed my July 4 “Feisty Female” article on Nancy Morgan Hart, you can read it here.

While their menfolk were off fighting the Union, many Southern women stepped up to defend their homes and families. One group of females in LaGrange, Georgia, however, officially banded together and formed an all-female militia. They called themselves the Nancy Harts in honor of Revolutionary War heroine and fellow Georgian Nancy Morgan Hart. In case you missed my July 4 “Feisty Female” article on Nancy Morgan Hart, you can read it here.

After the LaGrange Light Guards of the Fourth Georgia Infantry left on April 26, 1861, two wives, Nancy Hill Morgan and Mary Alford Heard, decided to form their own all-female militia. About forty women attended the first meeting which was held at a schoolhouse on the grounds of United States Senator Benjamin Hill’s home. The women, inexperienced with both firearms and military procedures, secured the assistance of Dr. A.C. Ware, a local physician who had been exempted from military service, to assist them in their training. Dr. Ware was elected their first captain, according to Atlanta’s Southern Confederacy newspaper on June 1, 1861:

After the LaGrange Light Guards of the Fourth Georgia Infantry left on April 26, 1861, two wives, Nancy Hill Morgan and Mary Alford Heard, decided to form their own all-female militia. About forty women attended the first meeting which was held at a schoolhouse on the grounds of United States Senator Benjamin Hill’s home. The women, inexperienced with both firearms and military procedures, secured the assistance of Dr. A.C. Ware, a local physician who had been exempted from military service, to assist them in their training. Dr. Ware was elected their first captain, according to Atlanta’s Southern Confederacy newspaper on June 1, 1861:

We are informed that the ladies of LaGrange, to the number of about forty organized themselves on Saturday last, into a military corps for the purpose of drilling and target practice. They elected Dr. A.C. Ware as their Captain, and, we believe, resolved to meet every Saturday.

Not long after the training began, Nancy Morgan and Mary Heard were elected as captain and first lieutenant, respectively. They were apparently quickly learning how to organize militarily – regiment leaders, sergeants, corporals and a treasurer were added. The “Nancy Harts” or “Nancies” began meeting twice as week to drill and train using William J. Hardee’s Rifle and Light Infantry Tactics. Years later a member of the Texas United Daughters of the Confederacy, Mrs. Forrest T. Morgan, reflected on what it might have been like:

I am sure this company presented a curious, odd, and singular spectacle as it met in Harris Grove, a beautiful and picturesque spot, with its magnificent trees to shelter them from the glare of light or sultry heat of the midsummer days, where they went often for target practice or drill…They met twice a week at the grove in the day, and at night on the courthouse square, with the moon and stars looking down with their majestic and glorious illumination to light the earth with their radiancy; while the captain could be heard in clear voice giving commands: “Shoulder arms, right face, forward, march!”

Prizes were offered as incentives to become better markswomen. There were several unfortunate incidents, but eventually they became expert and accurate shots.

The Nancy Harts continued to drill and train throughout the war, but even so the services they provided were mostly those of nurses to wounded soldiers, especially in the latter half of the war when LaGrange became a treatment center. Some patients were even sent to the women’s homes to receive individual care.

The Nancy Harts weren’t the only all-female militia group to organize during the Civil War, but likely the most diligent in terms of continuously drilling weekly for four years. With the exception of Sherman’s campaign on Atlanta which sent alarms throughout the area, LaGrange had remained mostly untouched by the war.

Near the end of the war, however, the women would indeed face the enemy. On April 17, 1865, in response to word of Union troops advancing toward LaGrange, the Nancy Harts marched to the grounds of LaGrange Female College to wait for the troops to arrive. When the Union cavalry arrived, Captain Nancy Morgan ordered the women to fall into a line of battle.

Perhaps alarmed at seeing a group of women rise to defend a town, a captured Confederate major stepped in to help negotiate the surrender of LaGrange to Colonel LaGrange (a coincidence his name was the same as the town’s). In return for their peaceful surrender, Colonel LaGrange agreed to spare private homes and land, although his troops did destroy facilities that were related to the Confederate war effort, such as the tannery and railroad.

After the war the United Daughters of the Confederacy formed a LaGrange chapter, led by a former member of the Nancy Harts. As one would imagine, the Nancy Harts became a symbol of LaGrange civic pride in the ensuing years. The Ladies Home Journal published an article about them in 1904 and in 1957 a Georgia state historical marker was placed in front of the LaGrange courthouse. The Nancy Harts had but one actual encounter with the enemy on that day in April of 1865, but in the early 1900’s Mrs. Forrest T. Morgan would reflect:

Thus it was that the girl soldiers rendered the Southern cause valuable service. They were never called to field duty, it is true, but they stood ever in readiness and rendered a service equally effective as guards over the defenseless and their homes.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Surname Saturday: Goforth

Today’s surname is another that is somewhat unique and thought to be a variant of the more common Gifford surname. It is believed to be an old French name introduced after the Norman Conquest of 1066 and found especially in the northern counties of Yorkshire and Lincolnshire.

The Old French term “giffard” means “chubby-cheeked” or “round-faced person”. Another theory is that “giffard” is a derogatory form of “giffel,” which means “jaw.” One of the first instances of the surname was recorded in the Domesday Book of 1086 as Walter Gifhard.

Modern variations of the surname include Giffard, Gifford, Jefferd, Jefford, Gofford, Gofforth, Gayforth and many more. According to The Internet Surname Database, the variations with “th” are the result of mistaken etymology from the Olde English “ford” which in Middle English was recorded as “forth.” The first recorded spelling of this surname was the christening record of Richard Gofforth on April 4, 1550 in Yorkshire.

Modern variations of the surname include Giffard, Gifford, Jefferd, Jefford, Gofford, Gofforth, Gayforth and many more. According to The Internet Surname Database, the variations with “th” are the result of mistaken etymology from the Olde English “ford” which in Middle English was recorded as “forth.” The first recorded spelling of this surname was the christening record of Richard Gofforth on April 4, 1550 in Yorkshire.

One of the early American immigrants, William Goforth, was born in Yorkshire and believed to have been a grandson of George Tuttle Goforth of Yorkshire, according to The Goforth Genealogy. I was intrigued by Canadian Jonathan Goforth’s story as the first missionary to represent the Presbyterian Church of Canada in China – what an appropriate name for a missionary!

William Goforth

William Goforth was born in 1631 in Yorkshire to parents Miles and Mary Goforth. Many Goforth family historians believe William had two wives, the first bearing him a son named Aaron (her name is unknown) who was born in 1660. William then married Anne Skipwith in 1662.

Sometime in the 1650’s William became a Quaker, as did Anne and her widowed mother, Honora Saunders Skipwith. Notably, Honora was a Quaker martyr in 1679, dying as a prisoner in York Castle. Perhaps William and Anne met at one of the Quaker meetings held in Yorkshire.

Late in the summer of 1677 William and Anne, along with their six children, boarded the Fly-Boat “Martha” and immigrated to America, arriving on October 28, 1677. The settlers were destined for a new Quaker colony in New Jersey, later the Burlington area and about thirty miles from where William Penn founded Philadelphia in 1682.

Quakers left England because of religious persecution, but upon arrival in the colonies found that the Puritans had written laws to keep them out of New England. Thus, there were at that time few places where Quakers were welcome. The Puritans regularly persecuted people of other faiths, yet seemed to be particularly disdainful of the Quaker faith. For more background on the persecution of Quakers by Puritans, see this article.

Soon after arriving, William purchased a lot on Burlington Island, located in the Delaware River, and a small tract of farming land on the mainland. The children of William and Anne were George, William, John, Susannah, Miles, Zachariah and Thomas (believed to have been born around 1677 so perhaps soon after their arrival).

Tragically, William died in 1678 and Anne would later marry a widower by the name of William Oxley (Anne Skipwith Goforth Oxley – quite a name).

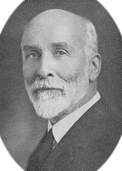

Jonathan Goforth was born on February 10, 1859 in Oxford County, Ontario to parents Francis and Jane Goforth. His parents had immigrated to Canada from England following their marriage, and Jonathan was the seventh of their eleven children. His parents were poor and their children were expected to work on the family farm six months out of each year. Nevertheless, Jonathan was able to keep up with his studies and excel. His mother taught him how to pray and memorize scriptures.

At the age of fifteen his father placed him in charge of another farm located about twenty miles from the family home. Leaving it to Jonathan’s care, his father would return later in the summer to inspect. When his father came in the fall he found fields full of ripening grain. Jonathan would later relate his father’s approval was indicated by a smile. In turn he would use the story to convey a Christian message: “That smile was all the reward I wanted. I knew my father was pleased. So will it be, dear Christians, if we are faithful to the trust our Heavenly Father has given us. His smile of approval will be our blessed reward.”

Jonathan became a Christian at the age of eighteen as a result of the ministry of Reverend Lachlan Cameron. Although his goal in life had been to become a lawyer, he instead became involved in his church. After hearing Dr. George McKay, a missionary to Formosa, Jonathan answered the call to missionary service. To prepare he enrolled at Knox College in Toronto, a theological institution later affiliated with the Presbyterian Church of Canada.

Jonathan the poor farm boy was ridiculed for his handmade clothing. To remedy the situation he purchased fabric for a local seamstress to create a more fashionable wardrobe. His classmates learned of his plan and one night forced him to parade up and down the hallway while they mocked him. He prayed for strength to endure and years later would still lament that such a thing could happen at a Christian college.

During his time at Knox he evangelized in the slums of Toronto and it was there he learned to trust God for his every need, for often he would be down to his last penny. God was faithful, however. During his mission work Jonathan met Rosalind Bell-Smith, she of a cultured and well-to-do Toronto family. Her first impression may have been the shabbiness of his dress, but a few days later she would find reason to look beyond the outward appearance. While attending a meeting she picked up Jonathan’s heavily marked-up Bible, almost in shreds from heavy use. At that point, she decided that he was the man she wanted to marry.

A few months later Rosalind accepted Jonathan’s marriage proposal with no stipulations except that she made him promise that he would always put the Master’s work ahead of her. Little did she know what that meant – instead of spending money on an engagement ring, Jonathan decided to purchase Christian tracts for China. The couple married on October 25, 1887 and on February 4, 1888 sailed to China for their first missionary assignment under the auspices of the Presbyterian Church of Canada. Their commission was to pioneer work in the North Honan Province.

Not long after their arrival, their hut burned down along with all their possessions, even their wedding gifts and photographs. Before they had reached the province, Jonathan received a message from Hudson Taylor, another (famed) missionary to China, warning him of great obstacles ahead and the need for divine help. The burning of their home was the first of many trials the Goforths would endure.

As with any missionary endeavor the Goforths experienced difficulties adapting to the culture, often separated from one another for long periods of time. Five of their eleven children were buried in China. Another struggle was learning the Chinese language. Although he studied diligently Jonathan seemed to make little progress, yet he was undeterred.

His attempts at preaching weren’t well received by the Chinese – they couldn’t understand him. Yet Jonathan believed he had been called to reach the Chinese people for Christ. One day he picked up his Chinese Bible, went to the chapel and began to preach in fluent Chinese, astounding his audience. Jonathan had expected God to provide a miracle and He did! He discovered two months later that Knox College students held a special prayer meeting “just for Goforth” – it was at the precise time he was able to suddenly master the Chinese language!

Jonathan and Rosalind opened their home to the Chinese and ministered to them there. During one period of time some twenty-five thousand men and women passed through their home and he was able to preach to them. Jonathan would speak to the men and Rosalind would meet with the women in the courtyard. It was a unique approach for they had no plans to build schools or hospitals as was the practice of many missions.

Jonathan was also an itinerant minister, traveling to villages and away from his family for weeks at a time. In 1900 their daughter Florence was stricken with meningitis and died. Soon after her death they were forced to flee the Boxer Rebellion. They made their way to Shanghai by cart and then boat. One of the children fell ill and along the way they heard cries of “kill these foreign devils.” At one point they were attacked with a barrage of stones, and as Jonathan stepped forward to reason with his attackers, he was struck with a sword and wounded severely but managed to escape. After reaching Shanghai they returned to Canada until the rebellion subsided.

The Goforths returned to Honan in 1901, but Jonathan’s ministry, inspired by accounts of revival in Wales, would evolve into that of evangelist and revivalist. His firebrand-style ministry in Korea and later in Manchuria was well received. He continued ministering in Manchuria until departing China in 1934.

Although blind and in failing health when he left China, Jonathan continued his ministry in Canada for the next two years until he passed away on October 8, 1936. On the last Sunday before he died Jonathan Goforth preached four times. Congregants gave the following impression:

As Mr. McPherson led Dr. Goforth into the pulpit he walked with firm step, head erect, and face aglow with the joy of Christ, the sightless eyes were turned upward as if he could see. The congregation listened with marked attention and stillness as with radiant joy, as seeing the Lord he loved, he delivered his address in the power of the Spirit.

Rosalind passed away in 1942 and both are buried in the Mount Pleasant Cemetery in Toronto. Their joint tombstone reads: “They glorified God and loved man.”

Often criticized for his fiery delivery and “emotionalism”, Jonathan would say, “I love those that thunder out the Word. The Christian world is in a dead sleep. Nothing but a loud voice can awake them out of it.”

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Wild West Wednesday: Jefferson Randolph “Soapy” Smith, Con Artist Extraordinaire

July 8, 1898 was an eventful day in Skagway, Alaska. A scoundrel by the name of Jefferson Randolph “Soapy” Smith met his untimely demise. Soapy had been making a name (and not a good one) for himself for years from Texas to Colorado to Alaska. Conduct a search at the Library of Congress’ Chronicling America web site or at Newspapers.com and you will find hundreds of references to “Soapy Smith” from the early 1870’s through the early 1920’s. To say he was notorious might be an understatement.

July 8, 1898 was an eventful day in Skagway, Alaska. A scoundrel by the name of Jefferson Randolph “Soapy” Smith met his untimely demise. Soapy had been making a name (and not a good one) for himself for years from Texas to Colorado to Alaska. Conduct a search at the Library of Congress’ Chronicling America web site or at Newspapers.com and you will find hundreds of references to “Soapy Smith” from the early 1870’s through the early 1920’s. To say he was notorious might be an understatement.

Jefferson Randolph Smith II was born in Coweta County, Georgia on November 2, 1860 to parents Jefferson Randolph and Emily (Edmundson) Smith, Sr. His family was prosperous; his great-grandfather had owned one of the largest plantations in the area and his father was a lawyer. As with so many Southern families their fortunes were depleted by the Civil War, so Jeff (as he liked to be called) and his family moved to Round Rock, Texas in 1876.

Jefferson Randolph Smith II was born in Coweta County, Georgia on November 2, 1860 to parents Jefferson Randolph and Emily (Edmundson) Smith, Sr. His family was prosperous; his great-grandfather had owned one of the largest plantations in the area and his father was a lawyer. As with so many Southern families their fortunes were depleted by the Civil War, so Jeff (as he liked to be called) and his family moved to Round Rock, Texas in 1876.

This article is no longer available for free at this site. It was re-written and enhanced, complete with footnotes and sources and has been published in the August 2018 issue of Digging History Magazine. Should you prefer to purchase the article only, contact me for more information.

This article is no longer available for free at this site. It was re-written and enhanced, complete with footnotes and sources and has been published in the August 2018 issue of Digging History Magazine. Should you prefer to purchase the article only, contact me for more information.

I invite you to check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Tombstone Tuesday: Zebulon Frisbie

Zebulon Frisbie was born July 4, 1801 in Orwell, Bradford County, Pennsylvania to parents Levi and Phebe (Gaylord) Frisbie. Phebe’s father, Aaron Gaylord, had been slain at the Battle of Wyoming on July 3, 1778. Levi was a private in the Connecticut militia and it’s uncertain as to whether he served in the Revolutionary War beyond his service in the state militia. One family history source states that Levi and his brother Abel were accused of sympathizing with the British in 1777, although both were later exonerated.

Zebulon Frisbie was born July 4, 1801 in Orwell, Bradford County, Pennsylvania to parents Levi and Phebe (Gaylord) Frisbie. Phebe’s father, Aaron Gaylord, had been slain at the Battle of Wyoming on July 3, 1778. Levi was a private in the Connecticut militia and it’s uncertain as to whether he served in the Revolutionary War beyond his service in the state militia. One family history source states that Levi and his brother Abel were accused of sympathizing with the British in 1777, although both were later exonerated.

Around 1800 Levi and Phoebe and their four children moved to Bradford County, Pennsylvania where Zebulon, their sixth child (one had died), was born in 1801. His siblings were: Chauncey, Levi Randall (died at birth), Laura, Catherine and Levi, Jr. Zebulon was named after his grandfather Zebulon Frisbie.

The journey from Connecticut to Pennsylvania was arduous since much of the land at that time was untamed wilderness. The Frisbies, although of Puritan descent and Episcopalian, helped found the Orwell Hill (Presbyterian) Church in 1803. According to The History of Bradford County, Pennsylvania, Levi was the first tanner in the county and “a man of splendid physique.” Zebulon, the youngest child, learned his father’s trade, joining his brother Chauncey later to take over Levi’s business. After a time, however, they sold the tannery and farmed.

The journey from Connecticut to Pennsylvania was arduous since much of the land at that time was untamed wilderness. The Frisbies, although of Puritan descent and Episcopalian, helped found the Orwell Hill (Presbyterian) Church in 1803. According to The History of Bradford County, Pennsylvania, Levi was the first tanner in the county and “a man of splendid physique.” Zebulon, the youngest child, learned his father’s trade, joining his brother Chauncey later to take over Levi’s business. After a time, however, they sold the tannery and farmed.

Zebulon married Polly Goodwin on December 4, 1828. Although Polly was eleven years younger than Zebulon and had been born in Connecticut, she came to Bradford County to live with her uncle James Cowles at the age of six after being orphaned. Zebulon and Polly had ten children: Addison Cowles (1829); Warren Rush (1831); William Lawson (1834); Chauncey Montgomery (1837); Eliza Maria (1839); Ruby Hannah (1843); Orrin Goodwin (1845); Emily Phebe (1847); Mary Ellen (1849) and Olin Gaylord (1852). Eliza Maria, Orrin Goodwin and Emily Phebe died in early childhood.

Zebulon farmed Levi’s property and, as evidenced by the 1840 and 1850 censuses, he cared for his elderly parents. In 1840 Levi and Phebe were living with him. By 1850 only his mother remained with his family as Levi had passed away in 1842. In addition to his work as a farmer, Zebulon participated in the civic affairs of his community, serving eighteen years as a Justice of the Peace, and from 1868-1873 serving as an Associate Judge of the Bradford County Court.

Zebulon was an elder in the Orwell Hill Church for many years, and according to one family historian, “was a man without ostentation, of exemplary life, genial and sociable and highly respected by his fellow citizens.” Politically he was a Whig and upon that party’s demise joined the Republican Party, “an ardent supporter of its principles.”

In 1860 six of their children were still living at the family farm. By 1870 only their two youngest children Mary Ellen and Olin remained at home. Chauncey and his wife Emogene were also enumerated in the same household that year. Mary Ellen may have been their only child to remain single. In 1880 at the age of twenty-nine she was living with them and perhaps caring for her aged parents, in addition to her occupation as a dress maker.

Zebulon became ill in August of 1881 and on the 29th, ten hours after being stricken, he passed away. According to The History of Bradford County, Pennsylvania, “his loss was sorely felt in all sections of the county.” Polly lived a few more years and passed away on April 17, 1887. They are buried in the Darling Cemetery in Orwell.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Surname Saturday: Hutchins-Hutchinson-Hutchings

Even though these surnames share the same Scottish origin, the family crests are distinct and different. “Hutchins”, “Hutchings” and “Hutchinson” are variations of a name first used by Viking settlers in ancient Scotland, all derived from a diminutive form of Hugh, or “Huchon.” “Hutchinson” would, of course, mean “son of Hugh.”

According to the web site “Forbears” these surnames are distributed as follows: Hutchings is found in the south and west of England, mainly Somerset, while Hutchinson is confined to the north, especially County Durham and frequent in Northumberland, Cumberland and in North and East Ridings.

According to the web site “Forbears” these surnames are distributed as follows: Hutchings is found in the south and west of England, mainly Somerset, while Hutchinson is confined to the north, especially County Durham and frequent in Northumberland, Cumberland and in North and East Ridings.

During the reign of Edward III (1327-1377) records mention John Huchoun of Somerset and Isota Huchon of Wiltshire. Willelmus Huchon was listed in the Yorkshire Poll Tax of 1379. Later, similar names appear in Scotland: James Huchonsone (Glasgow, 1454); John Huchonson (Aberdeen, 1466); William Huchison (Ardmanoch, 1504). Two brothers, George and Thomas Hutcheson, founded a hospital in Glasgow in the 1600’s.1 Spelling variations include: Hutcheon, Hutchon, Houchin, MacCutcheon, MacQuestion and many more.2

Update: I received some comments on this article which shed more light on this surname, its origins and its variations. Please refer to those comments made on 05 May 2016 below. One thing I’ve found when researching surnames — everyone has an opinion as to origin and the sources I used originally may or may not have correctly represented the origins of the surname (one reason why I don’t do many Surname Saturday articles of late). I have also updated the paragraph above with two footnotes (at the time I wrote the article I did not have footnote capability). Originally, the article was written as part of a six-story arc on The Last Men of the Revolution (see William Hutchings below). Thanks to the reader who stopped by and commented to shed more light on this surname. — Sharon Hall (05 May 2016)

Following are the stories of a few American families bearing these surnames. I include a story of an early Hutchins just because of his unusual forename. Also included is the story of one of the remaining six veterans of the Revolutionary War who were photographed and interviewed for Reverend Elias Hillard’s 1864 book, The Last Men of the Revolution.

This entire article has been enhanced and published in the May 2018 issue of Digging History Magazine. Should you prefer to purchase the article only, contact me for more information. I invite you to check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

This entire article has been enhanced and published in the May 2018 issue of Digging History Magazine. Should you prefer to purchase the article only, contact me for more information. I invite you to check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Feisty Females: Nancy Morgan Hart, War Woman

One biographer describes today’s “Feisty Female” as “a woman entirely uneducated, and ignorant of all the conventional civilities of life, but a zealous lover of liberty.” (The Women of the American Revolution, Volume 2 by Elizabeth Fries Ellet).

One biographer describes today’s “Feisty Female” as “a woman entirely uneducated, and ignorant of all the conventional civilities of life, but a zealous lover of liberty.” (The Women of the American Revolution, Volume 2 by Elizabeth Fries Ellet).

She was born Nancy (or Nancy Ann) Morgan, date uncertain (perhaps as early as 1735 or as late as 1747), and later married Benjamin Hart, Sr. She and Benjamin migrated from North Carolina to Georgia in the early 1770’s, settling in the Broad River valley (Wilkes County). According to historical records, Nancy and Benjamin had eight children, six sons and two daughters: Morgan, John, Thomas, Benjamin, Lemuel, Mark, Sarah and Keziah (one of the daughters apparently called “Sukey”).

She is said to have regarded her husband as a “poor stick,” perhaps because he was not as fiercely patriotic. It is believed that she might have “worn the pants in the family,” so to speak. Although illiterate she well knew how to survive on the frontier, being an expert herbalist and, despite the fact she was cross-eyed, an excellent shot.

She is said to have regarded her husband as a “poor stick,” perhaps because he was not as fiercely patriotic. It is believed that she might have “worn the pants in the family,” so to speak. Although illiterate she well knew how to survive on the frontier, being an expert herbalist and, despite the fact she was cross-eyed, an excellent shot.

In physical appearance she was said to have “a broad, angular mouth,” a towering figure of six feet in height, red hair and a smallpox-scarred face. One account described her as having “no share of beauty – a fact she herself would have readily acknowledged had she ever enjoyed an opportunity of looking into a mirror.”

Politically, she was with the “liberty boys,” her term for the Whigs of Wilkes County. She was not a friend of the Tories of Wilkes County, who, even though intimidated by her, scarcely missed an opportunity to taunt, tease or annoy her. The local Indians referred to her as “Wahatche” which some believe meant “war woman.”

Her exploits as a patriot and spy are legendary in Georgia history. Benjamin was frequently was away serving in the Georgia militia and it was up to her to protect their home and family. She would often disguise herself as a simple-minded man and wander into Tory camps to gather information for the patriots. On February 14, 1779 the Battle of Kettle Creek was a narrow victory for the patriots and some historians believe that Nancy was present there that day.

The more legendary acts of courage occurred at the Hart cabin near the Broad River. One night a Tory crept up to their home and peeked in through a crack between the logs. One of the children noticed the eyeball and secretly informed Nancy. At the time she was making soap around the hearth – she scooped up a ladle-full and flung it in the direction of the would-be spy. Disabled, the Tory was hog-tied and turned over to the local militia.

The most famous story of Nancy Hart’s feistiness and courage occurred when a group of five or six Tories stopped by her home while looking for a Whig leader. The man had just come through Nancy’s house where she directed him to hide in the nearby swamp. When the Tories arrived she mis-directed them, and when they realized they had been duped returned and demanded a meal after shooting her prized turkey.

The Tories stacked their weapons in the corner, demanded wine, which Nancy provided, and began to become intoxicated. Meanwhile, Nancy sent her daughter Sukey to the spring for water. Not only was Sukey to fetch water but blow a conch shell which would signal to those working in the fields that Tories were nearby.

As Nancy began to serve her guests, she passed repeatedly between them and their stacked weapons, secretly passing them one by one through a chink in the wall to Sukey. The Tories began to realize what was happening and one of them jumped up and moved towards her even though she threatened to shoot. The man ignored her warning, stepped forward and was shot dead by Nancy. She grabbed another gun and sent Sukey to bring help. The other men were held off by Nancy until her husband and neighbors arrived. According to The Women of the American Revolution, Nancy demanded they surrender “their damnatory carcasses to a whig woman.” The men wanted to shake hands upon their surrender but she would have none of it.

When Mr. Hart and his neighbors arrived, they wanted to shoot the Tories, but Nancy insisted they had surrendered to her. At this point she had reached the boiling point apparently, swearing that “shooting was too good for them.” Instead of shooting them, the remaining Tories were taken outside and hung. The story was later validated in 1912 when railroad workers unearthed a row of six skeletons, buried about three feet underground in a spot near the location of the old Hart cabin.

The Harts continued to live in the Broad River area following the Revolutionary War. Sometime in the 1790’s Nancy found religion and joined the Methodists. Former Georgia governor George R. Gilmer, whose mother knew Nancy, remembered that she “went to the house of worship in search of relief. She . . . became a shouting Christian, [and] fought the Devil as manfully as she had [once] fought the Tories.” (New George Encyclopedia)

Shortly after the Harts moved to Brunswick in the late 1790’s, Benjamin died. Nancy returned to Broad River only to find a flood had washed away the cabin. She instead settled with her son John in Clarke County near Athens. John Hart migrated with his family to Henderson County, Kentucky around 1803. Nancy would remain there until her death in 1830.

The Daughters of the American Revolution later erected a replica of the Broad River cabin, using chimney stones from the original structure. She has been memorialized by Georgians in numerous ways over the years. Hart County with its county seat of Hartwell were both named for Nancy Morgan Hart. Nearby are Lake Hartwell and the Nancy Hart Highway (Georgia Route 77).

Inspired by her courage, several women in LaGrange, Georgia formed a militia named the “Nancy Harts” to defend their town from the Yankees during the Civil War. More about the Nancy Harts later . . . stay tuned.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Tombstone Tuesday: Alexander Milliner (1760-1865)

Today’s Tombstone Tuesday subject was one of the last six Revolutionary War veterans featured in Reverend Elias Hillard’s book, The Last Men of the Revolution, published in 1864. At the time of the veterans’ interviews they were all over the age of one hundred. Previous articles of three other veterans can be found here, here and here. This week’s Surname Saturday article will feature William Hutchings and next Monday’s article will finish the series with Lemuel Cook’s story.

Today’s Tombstone Tuesday subject was one of the last six Revolutionary War veterans featured in Reverend Elias Hillard’s book, The Last Men of the Revolution, published in 1864. At the time of the veterans’ interviews they were all over the age of one hundred. Previous articles of three other veterans can be found here, here and here. This week’s Surname Saturday article will feature William Hutchings and next Monday’s article will finish the series with Lemuel Cook’s story.

Alexander Milliner was born on March 14, 1760 in Quebec, Canada. In Hillard’s account, Alexander’s parents’ names aren’t mentioned. His father was an English goldsmith who came over with Major General James Wolfe as an artificer (a skilled craftsman or mechanic for the armed forces). At the Battle of Quebec on September 13, 1759, Wolfe was killed. Alexander’s father died the same day, but not from a battle wound. At the end of the battle his father laid down to drink from a spring and “never rose again; the cold water, in his heated and exhausted condition, caus[ed] instant death.”

Alexander Milliner was born on March 14, 1760 in Quebec, Canada. In Hillard’s account, Alexander’s parents’ names aren’t mentioned. His father was an English goldsmith who came over with Major General James Wolfe as an artificer (a skilled craftsman or mechanic for the armed forces). At the Battle of Quebec on September 13, 1759, Wolfe was killed. Alexander’s father died the same day, but not from a battle wound. At the end of the battle his father laid down to drink from a spring and “never rose again; the cold water, in his heated and exhausted condition, caus[ed] instant death.”

This article is no longer available for free at this site. It was re-written and enhanced, complete with footnotes and sources and has been published in the July 2018 issue of Digging History Magazine. Should you prefer to purchase the article only, contact me for more information.

This article is no longer available for free at this site. It was re-written and enhanced, complete with footnotes and sources and has been published in the July 2018 issue of Digging History Magazine. Should you prefer to purchase the article only, contact me for more information.

I invite you to check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Surname Saturday: Chisholm

Chisolm

The Chisholm surname is Scottish and first recorded in thirteenth-century Roxburghshire, Roxburgh, the county that borders the English counties of Cumberland and Northumberland:

John de Chesehelme (1254)

John de Chesolm (1296)

It is a border name arising from the barony of Chisholme in Roberton, Roxburghshire. Some believe that the name was originally de Chesé and later “holme” was added when a Norman ancestor married a Saxon heiress, which might explain the two earliest spellings noted above. Spelling variations include: Chisholm, Chissolm, Chisham, Chisholme, Chism, Chisolm, Chisolt, Chissum, and others.

Adam Chisholme, who immigrated to America in the eighteenth century, did not choose to make the ocean voyage, but rather was transported as an indentured Jacobite prisoner.

Adam Chisholme

According to A Dictionary of Scottish Emigrants to the U.S.A., Adam Chisholme was transported on the Elizabeth and Anne, departing from Liverpool on either June 28 or July 28, 1716, and the ship arriving in Virginia sometime in late 1716. Family historians believe Adam was born circa 1695 in Scotland. He fought in the Jacobite uprising of 1715, or the “Fifteen” as it was also called, in support of an attempt to restore the Stuart monarchy to power in England.

The Jacobites, or “trouble makers” as they were labeled, failed and their punishment was banishment to the American colonies or the Caribbean Islands where they would be indentured servants for seven years. Over six hundred prisoners were transported in 1716 (another group would follow years later after the 1745 uprising).

It is believed that Adam was possibly indentured to William Morris of Hanover County, Virginia since Adam was a beneficiary named in Morris’ will in 1745. Records indicate that the majority of Jacobite prisoners were sent to the southern colonies, with Virginia receiving the most. North and South Carolina were both in need of white settlers and also accepted many prisoners.

It is believed that Adam was possibly indentured to William Morris of Hanover County, Virginia since Adam was a beneficiary named in Morris’ will in 1745. Records indicate that the majority of Jacobite prisoners were sent to the southern colonies, with Virginia receiving the most. North and South Carolina were both in need of white settlers and also accepted many prisoners.

After his indentured service was fulfilled, Adam married in 1725 and had three sons and one daughter. He died in Hanover circa 1756. For years the descendants of Adam Chisholme spelled their names either Chisholme, Chisholm or Chisolm. Some who migrated to South Carolina changed the spelling to Chism.

Although the Chisholm surname is of Scottish origins, many Scots, Irish and English who immigrated to America intermarried with the Cherokee and other tribes. Such was the case of Jesse Chisholm.

Jesse Chisholm

Jesse Chisholm was born in either 1805 or 1806. It’s certain that his father was Ignatius Chisholm, a merchant and slave trader of Scottish descent who worked in eastern Tennessee in the 1790’s. What is uncertain is the name of Jesse’s mother, a Cherokee woman and a relative of Chief Corn Tassel who had been killed in 1788. Some believe that Jesse’s Cherokee heritage dates back to his grandfather Captain John D. Chisholm marrying a Cherokee woman. After studying various family history theories, the first theory of his father marrying a Cherokee woman seems more plausible, although Ignatius and the unknown Cherokee appear to have parted ways later (before 1810 perhaps). Nevertheless, Jesse Chisholm’s striking features seem to indicate Cherokee heritage.

It is believed that Jesse was taken by his mother to Arkansas as part of the band of Cherokee led by Chief Tahlontskee in 1810. According to the Oklahoma Historical Society, Jesse was a member of a party searching for gold along the Arkansas River in 1826. In 1830 “he helped blaze a trail from Fort Gibson to Fort Towson, and in 1834 he was a member of the Dodge-Leavenworth Expedition, which made the first official contact with the Comanche, Kiowa and Wichita near the Wichita Mountains in southwestern Oklahoma.”

In 1836 he married the fifteen year-old daughter of Indian trader James Edwards, Elizabeth, who may have been part Creek Indian. They settled in the Creek Nation in current day Hughes County, Oklahoma where Jesse established a trading post. It appears that Jesse and Elizabeth had at least two children, sons Frank and William. Elizabeth died in 1845 or 1846.

Jesse was a successful trader and fluent in English as well as fourteen Indian dialects. His work as both a trader, scout and interpreter was carried out in Indian Territory, Texas and Kansas. He was acquainted with Sam Houston (Houston married Jesse’s aunt) who commissioned Jesse to contact the Indian tribes of West Texas. He was also instrumental in bringing other Indian groups to various councils to negotiate agreements with white settlers.

Jesse was a successful trader and fluent in English as well as fourteen Indian dialects. His work as both a trader, scout and interpreter was carried out in Indian Territory, Texas and Kansas. He was acquainted with Sam Houston (Houston married Jesse’s aunt) who commissioned Jesse to contact the Indian tribes of West Texas. He was also instrumental in bringing other Indian groups to various councils to negotiate agreements with white settlers.

By 1858 Jesse confined his work to western Oklahoma and expanded his trading operations in Oklahoma and established one post in Wichita, Kansas. His routes took him to Indian villages and U.S. army posts. During the Civil War, Jesse first worked with the Confederate Army, but by 1864 he was working as an interpreter for the Union and living in Wichita.

He continued trading and in 1865 Jesse and James Read loaded wagons in Fort Leavenworth and blazed a trail, establishing a trading post at Council Grove, near present-day Oklahoma City. The route became popular and was later named the Chisholm Trail. The trail would become especially vital to Texas cattlemen who wanted to sell their herds to eastern markets for greater profits.

In 1867 Joseph McCoy built stockyards in Abilene, Kansas, and O.W. Wheeler was the first Texas cattleman to herd steers (2,400) from Texas to Abilene. Before it was closed in 1885 more than five million cattle and a million mustangs would be herded across the Chisholm Trail. Interestingly, Jesse Chisholm never drove any cattle over the trail named after him. Jesse continued his work as a negotiator and interpreter. On March 4, 1868 he died of food poisoning – rancid bear meat – at Left Hand Spring, near present-day Geary, Oklahoma. It appears that his grave is located in a field. The inscription on his gravestone reads: “No one left his home cold or hungry.”

Jesse continued his work as a negotiator and interpreter. On March 4, 1868 he died of food poisoning – rancid bear meat – at Left Hand Spring, near present-day Geary, Oklahoma. It appears that his grave is located in a field. The inscription on his gravestone reads: “No one left his home cold or hungry.”

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!