Tombstone Tuesday: Thomas Jefferson Roach and His Sister Wives

Don’t let the title fool you. I don’t mean to imply that “Sister Wives” (as in the TLC reality show of the same name) means that the subject of today’s article, Thomas Jefferson Roach, was a polygamist. Quite the contrary, since according to family history Thomas was of the Baptist faith.

Don’t let the title fool you. I don’t mean to imply that “Sister Wives” (as in the TLC reality show of the same name) means that the subject of today’s article, Thomas Jefferson Roach, was a polygamist. Quite the contrary, since according to family history Thomas was of the Baptist faith.

This article has been removed from the free side of the site. It has been significantly updated with new research and featured in the March-April 2019 issue of Digging History Magazine. Purchase the issue here or contact me to purchase a copy of the article only.

This article has been removed from the free side of the site. It has been significantly updated with new research and featured in the March-April 2019 issue of Digging History Magazine. Purchase the issue here or contact me to purchase a copy of the article only.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? That’s easy if you have a minute or two. Here are the options (choose one):

- Scroll up to the upper right-hand corner of this page, provide your email to subscribe to the blog and a free issue will soon be on its way to your inbox.

- A free article index of issues is available in the magazine store, providing a brief synopsis of every article published in 2018. Note: You will have to create an account to obtain the free index (don’t worry — it’s easy!).

- Contact me directly and request either a free issue and/or the free article index. Happy to provide!

Thanks for stopping by!

Mothers of Invention: Stephanie Kwolek

If you’re in law enforcement or serve your country in the military, you have today’s “mother of invention” to thank for helping protect you when bullets are flying.

If you’re in law enforcement or serve your country in the military, you have today’s “mother of invention” to thank for helping protect you when bullets are flying.

Stephanie Louise Kwolek was born on July 31, 1923 in New Kensington, Pennsylvania to parents John and Nellie Kwolek. As a young girl, while watching her mother sew she became interested in fashion, drawing and designing patterns for doll clothes and later sewing her own clothes – at one point Stephanie thought she might pursue a career in fashion design. Her father, a foundry worker, died when she was ten years old, but during her early years he encouraged her to also explore nature.

She and her father would spend hours in the woods looking for plants, animals and insects. By her own account, like her father, she had a keen sense of curiosity and read more than most children her age. She would later remark that those characteristics set her apart from her peers and served her well later in her career.

After graduating from high school, Stephanie enrolled in the Carnegie Institute of Technology (now Carnegie Mellon University) in 1942 majoring in chemistry. She had considered various career paths before embarking on her education, including fashion design, teaching or pursuing a medical degree. At Carnegie, she was mentored by one of her chemistry professors, Dr. Clara Miller.

After graduating from high school, Stephanie enrolled in the Carnegie Institute of Technology (now Carnegie Mellon University) in 1942 majoring in chemistry. She had considered various career paths before embarking on her education, including fashion design, teaching or pursuing a medical degree. At Carnegie, she was mentored by one of her chemistry professors, Dr. Clara Miller.

In 1946 Stephanie graduated from the Margaret Morrison Carnegie College with a bachelor’s degree in chemistry. She thought she might take a job, save her money and later continue her education in medicine. At that time women were being offered jobs in the chemistry field, especially right after World War II when men were still serving or coming home from the war. Some women with advanced degrees, however, would remain in those jobs only a short time before taking jobs in academia.

Stephanie, interested in research, decided to take a different path, deciding that DuPont would offer her the best chance at pursuing her passion. She joined a team of chemists called the Pioneering Research Laboratory who had just a few years before discovered nylon, the first synthetic fiber.

Stephanie, interested in research, decided to take a different path, deciding that DuPont would offer her the best chance at pursuing her passion. She joined a team of chemists called the Pioneering Research Laboratory who had just a few years before discovered nylon, the first synthetic fiber.

Although Stephanie still thought she might attend medical school, she found the research work so interesting that she decided to forego that ambition and remain with DuPont. The opportunity to discover new things was extremely satisfying to her. She later remarked that her male supervisors were very much interested in their own work and mostly left her alone to conduct experiments and make her own discoveries – a perfect combination for someone who was already has a keen sense of both curiosity and creativity.

In 1965, due to the possibility of gasoline shortages, a need arose to replace the steel wires in automobile tires with a new synthetic fiber. Her assignment was to find a super-stiff, lightweight fiber and she began to experiment on a group of long-chain molecules called aromatic polyimides. She discovered that, under the right conditions, these polyimides would form liquid crystals – the solution was usually thick but this one was more fluid. One of her colleagues believed the fluidity was due to contamination and refused to spin it for her because it might clog his equipment.

After she eventually convinced him to spin it, both were pleasantly surprised to find it resulted in the stiffest and strongest fiber anyone had ever seen. Stephanie immediately realized she had just made a very important discovery – an “aha moment.” First called “Fibre B” it later became known as Kevlar when DuPont patented it in 1971.

DuPont found numerous ways to use the new synthetic fiber – fiber optics, reinforcing roads, tires, bicycles and hiking boots to space equipment and more. The idea to use the fiber, in multiple layers, for army helmets and bullet-proof vests came later, and as they say “the rest is history.” In 1987 the DuPont Kevlar Survivors Club was founded by law enforcement officers who owed their lives to the bullet-proof vest.

Between 1961 and 1986 Stephanie Kwolek was awarded seventeen patents, although after signing over royalties to DuPont she never earned any money from her invention. Another interesting fact about this amazing woman was that she never pursued any higher degree than the original bachelor’s degree she received in chemistry in 1946.

Between 1961 and 1986 Stephanie Kwolek was awarded seventeen patents, although after signing over royalties to DuPont she never earned any money from her invention. Another interesting fact about this amazing woman was that she never pursued any higher degree than the original bachelor’s degree she received in chemistry in 1946.

Stephanie never married and retired in 1986. After retirement she tutored high school students in chemistry, especially encouraging young women to pursue careers in the field. In 1995 she was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame, one of only four women to ever receive that honor. She was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame in 2003 and the Plastics Hall of Fame in 2004.

Stephanie Louise Kwolek died recently in Delaware on June 18, 2014 at the age of ninety.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Surname Saturday: Roach

Today’s surname originated in France, derived from the French word “roche” which means rocky crag or someone who lived near a rocky crag. After the Norman invasion in the late eleventh century, the name became more prevalent throughout both England and Ireland, but also could be found variously in Italy as “Rocca” or “Roca” and in the Netherlands or Belgium as “De Reorck.”

There are more than thirty spelling variations for this surname in addition to those listed above, including: Roche, Roache, LaRoche, LaRoach, DeLaRoach, Roche and many more. There is a suburb in Cork County, Ireland named Rochestown and there was once an influential Roche family in the same county. In England early records listed Ralph de la Roche of Cornwall in 1195 and Lucas de Roches of Hampshire in 1249.

There are more than thirty spelling variations for this surname in addition to those listed above, including: Roche, Roache, LaRoche, LaRoach, DeLaRoach, Roche and many more. There is a suburb in Cork County, Ireland named Rochestown and there was once an influential Roche family in the same county. In England early records listed Ralph de la Roche of Cornwall in 1195 and Lucas de Roches of Hampshire in 1249.

No doubt early Irish immigration and certainly the Irish Potato Famine of the 1840’s brought some of the Roach family to America’s shores. Depending on how old you are, you may or may not recognize the name of Harold Eugene Roach, grandson of Irish immigrants. His story follows.

Harold Eugene Roach

Harold Eugene “Hal” Roach was the grandson of Irish immigrants, born on January 14, 1892 in Elmira, New York to parents Charles and Mabel Roach. As a child he was a prankster whose antics got him expelled from both a Catholic and public school. At the age of sixteen his father thought a little traveling would help young Hal grow up.

Hal made his way west and worked in Seattle for a time selling ice cream from a horse-drawn wagon. His travels next took him to Alaska where he worked as a postman and unsuccessfully as a gold miner. After drifting back down to California, where he worked for a time in oil field construction, he landed a job in Hollywood as a cowboy extra in 1912.

Hal made his way west and worked in Seattle for a time selling ice cream from a horse-drawn wagon. His travels next took him to Alaska where he worked as a postman and unsuccessfully as a gold miner. After drifting back down to California, where he worked for a time in oil field construction, he landed a job in Hollywood as a cowboy extra in 1912.

His penchant for pranks and gags may have begun to serve him well because he soon worked his way from extra to minor actor to cameraman and then on to writing and assistant director. After just two years in the “business” Hal Roach rose to become a director and producer, especially in the genre of comedy.

For the next ten years he worked with comedy legend Harold Lloyd, a contemporary of Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton who was featured first in silent films and later “talkies” which featured daredevil-like feats and chase scenes. Hal Roach helped shape Lloyd’s career into one which set him apart from Chaplin and Keaton.

For the next ten years he worked with comedy legend Harold Lloyd, a contemporary of Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton who was featured first in silent films and later “talkies” which featured daredevil-like feats and chase scenes. Hal Roach helped shape Lloyd’s career into one which set him apart from Chaplin and Keaton.

He also had a hand in shaping the career of Will Rogers and the comedy team of Laurel and Hardy. In 1922, the Our Gang comedies began to be produced after, according to the New York Times, “sighting a group of frisky youngsters playing and quarreling in a lumber yard. Their spontaneous antics intrigued him as heady relief from the rouged mini-adults that stage mothers constantly shepherded into his office.”

The production of Our Gang comedies was scheduled around the lives of the children. As children “outgrew” the roles others were brought in to replace them. Some notable actors who appeared over the years were Jackie Cooper, Dickie Moore and Nanette Fabray.

The production of Our Gang comedies was scheduled around the lives of the children. As children “outgrew” the roles others were brought in to replace them. Some notable actors who appeared over the years were Jackie Cooper, Dickie Moore and Nanette Fabray.

After producing the series for sixteen years, Hal sold it to MGM which continued to produce it for another six years. The Little Rascals would become one of the most popular and beloved children’s television shows, still a source today of good, clean and nostalgic fun. Broadening the scope of his business beyond comedy, he began to produce dramas, westerns and action movies as well in the 1930’s. During World War II he produced both morale and propaganda films, working with actors Ronald Reagan and Alan Ladd.

Hal married Marguerite Nichols, an actress, and together they had two children: Hal, Jr. and Margaret. They were married twenty-six years before Marguerite passed away in 1940. In 1942 he married a secretary by the name of Lucille Prin with whom he had four more children: Elizabeth, Maria, Jeanne and Kathleen. Lucille died in 1981 and his children Hal, Jr., Elizabeth and Margaret also preceded him in death.

Hal married Marguerite Nichols, an actress, and together they had two children: Hal, Jr. and Margaret. They were married twenty-six years before Marguerite passed away in 1940. In 1942 he married a secretary by the name of Lucille Prin with whom he had four more children: Elizabeth, Maria, Jeanne and Kathleen. Lucille died in 1981 and his children Hal, Jr., Elizabeth and Margaret also preceded him in death.

Harold Eugene “Hal” Roach, legendary director and producer, lived to be over one hundred years old, passing away on November 2, 1992 in Los Angeles and was buried in his hometown of Elmira, New York. During his storied career he ran the Hal Roach Studios in Culver City, California, won three Academy Awards and helped shape the careers of actors and directors such as Jean Harlow, Janet Gaynor, Mickey Rooney, Frank Capra and more. Most of all he gave the world the gift of laughter.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

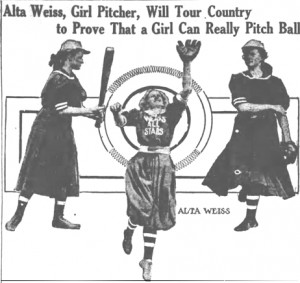

Feisty Females: Alta Weiss (In a League All Her Own)

When she was scarcely one year old, her father claimed his daughter could throw a corn cob at a cat with the skill and precision of any pitcher in the big leagues. Alta Weiss was born on February 9, 1890 in Berlin, Ohio to parents George and Lucinda Weiss and at the age of five she and her parents moved to Ragersville, Ohio where she came to be known as the town’s most famous resident.

When she was scarcely one year old, her father claimed his daughter could throw a corn cob at a cat with the skill and precision of any pitcher in the big leagues. Alta Weiss was born on February 9, 1890 in Berlin, Ohio to parents George and Lucinda Weiss and at the age of five she and her parents moved to Ragersville, Ohio where she came to be known as the town’s most famous resident.

At an early age her father encouraged her to keep playing, and by the time she was a teenager George had established a high school so that his “ace” daughter could play on the baseball team. He also built the Weiss Baseball Park in Ragersville. In 1907, while the family was vacationing in Vermilion, Ohio, she encountered some boys and offered to play catch with them. Little did they know what they would be witnessing – word of her skills as a pitcher spread.

According to the Baseball of Fame, after Alta struck out fifteen men the manager of Vermilion’s semi-pro team, the Independents, offered her a contract – she was seventeen years old. Each weekend she traveled to Vermilion from her home in Ragersville (127 miles) to pitch for the Independents. As one might imagine, she caused quite a stir and fans flocked to see her play. She was dubbed a “Girl Wonder.”

According to the Baseball of Fame, after Alta struck out fifteen men the manager of Vermilion’s semi-pro team, the Independents, offered her a contract – she was seventeen years old. Each weekend she traveled to Vermilion from her home in Ragersville (127 miles) to pitch for the Independents. As one might imagine, she caused quite a stir and fans flocked to see her play. She was dubbed a “Girl Wonder.”

The Sandusky Star-Journal reported on September 18, 1907:

Miss Weiss is no masculine girl, no tomboy, although her youth might excuse that, especially in consideration of the adulation she has received at the hands of the Vermilion fans, who this summer have gone wild over her work. She is no Amazon. She is merely the daughter of Dr. Augustus [George] Weiss, of Ragersville, Tuscarawas county, O., where she has played baseball with her father and the “kids” ever since she was old enough to sit up and take notice.

She wore a blue serge skirt with a sailor blouse, a baseball cap, heavy black cotton stockings and rubber shoes. “She wears no corset. She said so.” The newspaper story noted that she didn’t throw like a girl, nor did she flinch when balls came her way. “She threw the ball as straight as an arrow and as fast, and when the catcher threw it back to her it was no girly-girly toss ball, but a hot liner which she caught.” She had never played ball with girls.

Not only was she a “ace pitcher” she was pretty good at bat too. Folks seemed to be in awe of the fact that she was still quite feminine in appearance and manner. “The only womanliness which she may have lost was in her corset. She advises that no one attempt to wear corsets and play baseball.” Indeed! This was reported on September 18, 1907.

A week later the Sandusky Star-Journal was reporting that Alta would now suit up as a “real sure-enough ball player, clothes and all.” The day before Alta had ordered a baseball shirt, stockings, sweater, cap and spiked shoes. To complete the outfit she would wear bloomers and a short skirt, all made-to-order just for her. Her presence on the field continued to stir interest and by early October of 1907 the Humane Society was called upon to investigate whether she was of legal age (eighteen years old). Apparently nothing came of it because she continued to pitch and make headlines around the country.

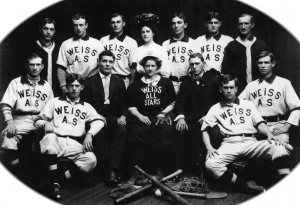

Dr. Weiss was his daughter’s biggest fan and when the 1907 season ended he built Alta a gymnasium where she could train during the winter, aiming to be in the “best trim” possible when the season opened the following spring. Her goals for the next season included earning enough money to buy her own car. Her father saw her great potential, however, and decided to purchase a half-interest in the Vermilion Independents, whereupon he changed the name to the “Weiss All-Stars.”

Alta, of course, was the star of the team and she was outfitted with a black uniform to set her apart from the white uniforms of her male team members. The team toured throughout Ohio, Kentucky, Indiana and Michigan, drawing large crowds wherever they went. It was customary for Alta to pitch five innings before taking a position at first base. This was occurring in the spring of 1908 while she was finishing her final year of high school. She was scheduled to graduate on June 6 but also scheduled to pitch in Dayton on June 7. The commencement date was moved up to May 21 to accommodate.

Alta, of course, was the star of the team and she was outfitted with a black uniform to set her apart from the white uniforms of her male team members. The team toured throughout Ohio, Kentucky, Indiana and Michigan, drawing large crowds wherever they went. It was customary for Alta to pitch five innings before taking a position at first base. This was occurring in the spring of 1908 while she was finishing her final year of high school. She was scheduled to graduate on June 6 but also scheduled to pitch in Dayton on June 7. The commencement date was moved up to May 21 to accommodate.

After the 1908 season Alta had earned enough money for college and enrolled in Wooster Academy. Her goal was to eventually become a doctor like her father and two years later she entered Starling College of Medicine. She still toured, however, and continued to earn money to put herself through school.

In 1914 Alta Weiss was the only female graduate of the Starling College of Medicine and played ball until her last game in 1922. In 1927 she married Johnny Hisrich of Ragersville. They lived in Norwalk, Ohio where she practiced medicine and he had an automotive garage. However, after twelve years of marriage the couple separated in 1939.

In 1914 Alta Weiss was the only female graduate of the Starling College of Medicine and played ball until her last game in 1922. In 1927 she married Johnny Hisrich of Ragersville. They lived in Norwalk, Ohio where she practiced medicine and he had an automotive garage. However, after twelve years of marriage the couple separated in 1939.

After her father died in 1946, Alta moved back to Ragersville to take over his practice. She retired after just a few years and was said to have become somewhat of a recluse – some say she spent her days sitting on her porch reading newspapers and watching the town kids play baseball.

Even after her retirement from baseball, newspaper articles would mention her name for years to come. Alta Weiss died on February 12, 1964, just three days following her seventy-fourth birthday. Her uniform was later sent to Cooperstown for a women’s baseball exhibit which opened in 2005.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Ghost Town Wednesday: Fourteen-Mile City

On May 26, 1863 a group of men (Barney Hughes, Thomas Cover, Henry Rodgers, Henry Edgar, William Fairweather, Bill Sweeney and others) were on their way back to Bannack, Montana, scene of a gold discovery the year before. After being diverted from their route by a band of Crow Indians, the men camped at Elk Park.

On May 26, 1863 a group of men (Barney Hughes, Thomas Cover, Henry Rodgers, Henry Edgar, William Fairweather, Bill Sweeney and others) were on their way back to Bannack, Montana, scene of a gold discovery the year before. After being diverted from their route by a band of Crow Indians, the men camped at Elk Park.

While the others were away from the camp, Edgar and Fairweather discovered gold. According to legend, they had spotted a piece of bedrock and hoped to find enough gold to purchase some tobacco in Bannack. What they actually found turned out to be one of the richest deposits of gold ever found in the United States.

Although the men tried to keep their discovery a secret, upon returning to Bannack word spread of a new gold strike. Fairweather led a group out of Bannack and about halfway to Alder Gulch they formed the Fairweather Mining District. The original discoverers would have first pick of the claims.

Although the men tried to keep their discovery a secret, upon returning to Bannack word spread of a new gold strike. Fairweather led a group out of Bannack and about halfway to Alder Gulch they formed the Fairweather Mining District. The original discoverers would have first pick of the claims.

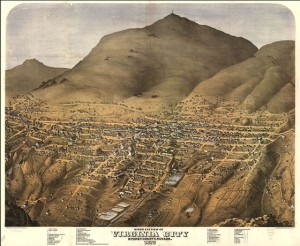

After the first wave of miners arrived in the gulch on June 6, it took only three months for the population to burgeon to over ten thousand. The mining towns that sprung up along the gulch were known as the “Fourteen- Mile City”: Junction City, Adobe Town, Nevada City, Central City, Virginia City, Bear Town, Highland, Pine Grove French Town, Hungry Hollow and Summit.

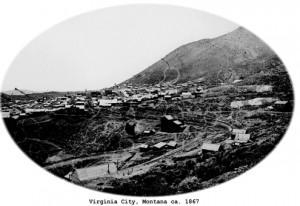

Virginia City had originally been called Verona and later proposed to be Verina in honor of Jefferson Davis’ wife. This was happening, of course, in the middle of the Civil War. Apparently thinking it either objectionable or imprudent to take sides, the name became “Virginia City” instead.

Virginia City quickly became one of the most prominent cities in Montana Territory – the first territorial capital and home of the first Montana newspaper, the Montana Post, and the first Montana public school. Just a mile and-a-half west was Nevada City – both towns were the sites of some wild and woolly events and the rise of a group known as the “Vigilantes of Montana” – more about that in next week’s “Wild West Wednesday” article.

Interestingly, the Montana Post reported in December of 1864 that three sisters by the last name of Canary (ages twelve, ten and one) were wandering the streets of Virginia City as beggars while their father gambled. Could this have been Martha Canary, a.k.a. Calamity Jane, who was born in 1852?

Neighboring Nevada City sprang up quickly as well, adding dozens of businesses – a dry goods store, dance halls, saloons and many more. Today the town, although mostly abandoned, is preserved in a unique way. Fourteen original buildings remain, but residents in the 1940’s and 1950’s replaced some of the dilapidated or destroyed sites with other buildings moved from other historic locations. Today the site is owned by the Montana Heritage Commission – sounds like it would be a great place to visit.

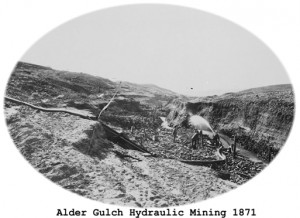

The primary method of gold extraction was placer mining, defined by Merriam-Webster as “the process of extracting minerals from a placer especially by washing, dredging, or hydraulic mining” and also known as free gold prospecting (dust, flakes and nuggets of gold). Between 1863 and 1866 it is estimated that thirty million dollars worth of gold was extracted in the gulch.

One source indicates that between 1863 and 1889 the United States Assay Office reported at least ninety million dollars in gold (which would be forty BILLION in today’s dollars). This despite the fact that by 1875 mining activity had been greatly curtailed and Virginia City had dwindled to less than eight hundred people. A significant portion of the remaining population were Chinese who continued to work abandoned claims.

With the dwindling fortunes of Virginia City came a significant change – the territorial capital was moved to Helena. Still, Virginia City hung on (and today still has about one hundred and thirty residents). In 1898 new mining machinery arrived, a dredge boat by the name of Maggie Gibson, and the town experienced a bit of a resurgence, although those operations would leave a permanent scar on the landscape.

By 1937 dredging had ceased – World War I and the Great Depression had taken a toll and weakened demand. When America entered World War II, gold mining was deemed a non-essential activity all over the country. The economic engine in the area today is found in tourist dollars after efforts to preserve these old mining towns was undertaken several years ago, although since World War II sporadic activity has been noted when gold prices have surged.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Tombstone Tuesday: Delilah Sixkiller Bushyhead

By her own admission before the Department of the Interior Commission to the Five Civilized Tribes on October 24, 1900, Delilah Sixkiller Bushyhead was around fifty years old, meaning she was probably born sometime between 1849-1851 in the Cherokee Nation (Oklahoma Indian Territory).

By her own admission before the Department of the Interior Commission to the Five Civilized Tribes on October 24, 1900, Delilah Sixkiller Bushyhead was around fifty years old, meaning she was probably born sometime between 1849-1851 in the Cherokee Nation (Oklahoma Indian Territory).

Her parents were Anderson “Peach-Eater” and E-Tse-Qua-Ni (or Ansequanah Sweetwater) Sixkiller. Peach-Eater was a brother to Redbird Sixkiller, father of legendary lawman Samuel Sixkiller and the subject of a recent article. Peach-Eater, his Cherokee name being Cha-ah-wah, was also elected to served as Councilor of the Goingsnake District in 1879.

On that day in 1900, Delilah was applying for citizenship in the Cherokee Nation as a full-blood Cherokee, although it appears she had previously been registered on the 1880 Roll as Delilah Sixkiller in the Saline District (northeastern part of Oklahoma Territory). She had also appeared as Delilah Bushyhead on the 1896 Roll living in Cooweescoowee. She had in fact lived in the Cherokee Nation her entire life. The commission was satisfied she met all requirements and was fully identified as a full-blood Cherokee Indian.

On that day in 1900, Delilah was applying for citizenship in the Cherokee Nation as a full-blood Cherokee, although it appears she had previously been registered on the 1880 Roll as Delilah Sixkiller in the Saline District (northeastern part of Oklahoma Territory). She had also appeared as Delilah Bushyhead on the 1896 Roll living in Cooweescoowee. She had in fact lived in the Cherokee Nation her entire life. The commission was satisfied she met all requirements and was fully identified as a full-blood Cherokee Indian.

It is unclear to me whether Delilah had ever been married before marrying Joseph Bushyhead on November 19, 1889. One source indicates, however, that Joseph had more than one wife. His first wife, Elizabeth Hair, died in January of 1878 and it’s possible he married another woman by the name of Ka-ho-ga Pigeon, who perhaps died before he married Delilah.

I believe that Joseph’s father, Jacob Bushyhead, was the brother of Reverend Jesse Bushyhead (see my Surname Saturday article). Since the Bushyhead family was known to be of the Baptist faith, it would be doubtful, in my opinion, that Joseph would have been a polygamist (but, of course, I could be wrong).

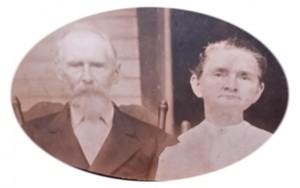

Nevertheless, Delilah and Joseph were married just over two years before he passed away on January 8, 1892 at the age of forty-two. Delilah passed away on November 1, 1910 and she and Joseph share a gravestone in the Woodlawn Cemetery in Rogers County, Oklahoma, providing evidence that Delilah was his third surviving wife and the other two had preceded both Delilah and Joseph in death.

I found only one reference to her in a book entitled History of the Cherokee Indians and Their Legends and Folk Lore by Emmet Starr. I did notice, however, that apparently Delilah was a popular Cherokee name. Maybe a Sixkiller or Bushyhead family member or historian will read this and provide more information, in which case I will update the article and re-post.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Surname Saturday: Bushyhead

Bushyhead

You won’t find today’s surname in Patronymica Britannica, nor will you find a family crest or coat of arms. I ran across the name recently, decided to research its origins and found it to be quite fascinating. The name appeared before the Revolutionary War and was first associated with a Scotsman by the name of John Stuart.

John Stuart was born in Scotland in 1718 to parents John and Christine (MacLeod) Steuart (John later dropped the “e”). In the spring of 1748 John arrived in Charles Town, South Carolina seeking economic opportunities. One source reports that he married Sarah (surname unknown) and together they had four children, three daughters and a son. He became a prominent member of Charleston society with membership in the St. Andrews Society, the Charleston Library Society, the Masons. Stuart also served in the South Carolina Militia, holding the rank of Captain.

In 1755, during the French and Indian War, Stuart was assigned to Fort Loudon in Cherokee country where he made the acquaintance of prominent Cherokees, including a leader by the name of Attakullakulla, or “The Little Carpenter” as the English called him. After Stuart was captured in 1760 his friendship with Little Carpenter was instrumental in his release following a siege by Cherokees on Fort Loudon.

In 1755, during the French and Indian War, Stuart was assigned to Fort Loudon in Cherokee country where he made the acquaintance of prominent Cherokees, including a leader by the name of Attakullakulla, or “The Little Carpenter” as the English called him. After Stuart was captured in 1760 his friendship with Little Carpenter was instrumental in his release following a siege by Cherokees on Fort Loudon.

In 1762 Stuart was appointed as a British Indian agent to all tribes south of the Ohio River and east of the Mississippi River, according to NCPedia. He was popular among the Cherokee, according to Revolutionary War in the Southern Back Country by James Swisher. The Cherokee gave him the title of “Beloved Father” and called him “Oonaduta” which translated means “Bushyhead” because of his curly red hair, typical of Scotsmen.

Swisher writes that Stuart took an Indian wife by the name of Sarah Henry (although another source says her name was Susannah Emory), but does not mention what became of his first wife. Nevertheless, whomever Stuart married, his wife was Cherokee and their children and descendants perpetuated the Bushyhead surname. Following are biographies of a father and son, two prominent members of the Bushyhead family and the Cherokee Nation.

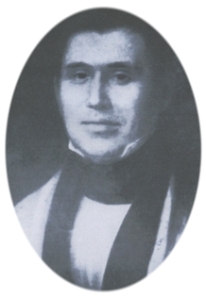

Reverend Jesse Bushyhead

Jesse Bushyhead, born in eastern Tennessee in 1804, was the grandson of John Stuart and his Cherokee wife. Their son, also called Oonaduta, married Nancy Foreman, a Cherokee maiden. As a child Jesse attended a Presbyterian and Congregational school at Candy Creek (later called the Candy Creek Mission).

After the studying the Bible in regards to baptism, Jesse joined the Baptist Church. In 1830 he was baptized by a Baptist elder and joined the church in Achaia, Tennessee in 1831. Jesse received a license to preach the following year and in 1833 was ordained. After serving as a co-pastor of the church in Achaia for a time, he founded a church at Amohi in 1835, the congregation largely consisting of members of the Cherokee Nation.

Jesse was a close friend of Baptist missionary Evan Jones who would often translate Jones’ messages into the Cherokee language. The two traveled together and also worked on translating portions of the Bible and other religious texts to the Cherokee language. He married twice, although his first wife’s name is unknown. His second wife, Eliza Wilkerson (or Wilkinson) bore him nine children. His oldest son, would become a prominent member of the Cherokee Nation (see his story below).

Jesse was a close friend of Baptist missionary Evan Jones who would often translate Jones’ messages into the Cherokee language. The two traveled together and also worked on translating portions of the Bible and other religious texts to the Cherokee language. He married twice, although his first wife’s name is unknown. His second wife, Eliza Wilkerson (or Wilkinson) bore him nine children. His oldest son, would become a prominent member of the Cherokee Nation (see his story below).

As a result of the Indian Removal Act of 1830, thousands of Indians, including Cherokee, Muskogee, Seminole, Chickasaw and Choctaw, were removed from the southeastern areas of the United States to Indian Territory (now Oklahoma). Jesse, although opposed to the removal, led a group of several hundred of his people to Indian Territory, arriving on February 23, 1838. The place was called Pleasant Hill near present day Westville, Oklahoma and approximately seventy miles from Fort Smith, Arkansas.

In 1844, following a brief illness, Reverend Jesse Bushyhead died and was buried in the Baptist Mission Cemetery. His grave is marked by a monument and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. One side reads:

In 1844, following a brief illness, Reverend Jesse Bushyhead died and was buried in the Baptist Mission Cemetery. His grave is marked by a monument and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. One side reads:

Sacred to the memory of Rev. Jesse Bushyhead, born in the old Cherokee Nation in East Tennessee, September, 1804; died in the present Cherokee Nation, July 17, 1844. “Well done, thou good and faithful servant; thou hast been faithful over a few things, I will make thee ruler over many things. Enter thou into the joy of thy Lord.”

The other side reads:

Rev. Jesse Bushyhead was a man noble in person and noble in heart. His choice was to be a true and faithful minister of his Lord and Master rather than any high and worldly position. He loved his country and people, serving them from time to time in many important offices and missions. He united with the Baptist Church in his early manhood and died as he had lived, a devoted Christian.

Dennis Wolfe Bushyhead

Dennis Wolfe Bushyhead was born on March 18, 1826 to parents Jesse and Eliza. Like his father his early education was received at the Candy Creek Mission and later at the Valley River Mission School in North Carolina (under the tutelage of family friend Evan Jones). Although his father led a group of Cherokees to Indian Territory in 1838, Dennis remained in school and eventually attended Princeton University briefly before his father’s death in 1844.

When Jesse died, Dennis returned to Indian Territory for a time before heading to California for the gold rush in 1849. After returning to Indian Territory in 1868, he served as Treasurer of the Cherokee Nation from 1871 until 1879. In 1879 he was elected Principal Chief, serving until 1887. During his tenure as Principal Chief, Dennis Bushyhead addressed issues such as grazing rights, tribal citizenship, education and railroad right-of-way.

When Jesse died, Dennis returned to Indian Territory for a time before heading to California for the gold rush in 1849. After returning to Indian Territory in 1868, he served as Treasurer of the Cherokee Nation from 1871 until 1879. In 1879 he was elected Principal Chief, serving until 1887. During his tenure as Principal Chief, Dennis Bushyhead addressed issues such as grazing rights, tribal citizenship, education and railroad right-of-way.

Dennis married Elizabeth Scrimsher and they had four children: Jesse Crary, Eliza, Catherine and Dennis, Jr. Following her death in 1882, he re-married Eloise Butler and had two more children, James Butler and Francis Taylor. Like his father, Dennis followed the Baptist faith throughout his life and died on February 4, 1898.

The community of Bushyhead, Oklahoma was named after Dennis and had a post office from 1898 until 1955. Today it is a census-designated place in Rogers County, Oklahoma, home to approximately thirteen hundred residents.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Feudin’ and Fightin’ Friday: The Hay Meadow Massacre

It was a Kansas feud, a county seat war, but the massacre occurred in a strip of land which is now part of Oklahoma, the “panhandle” part. In 1888, however, it was called the “Neutral Strip” or “No Man’s Land”.

It was a Kansas feud, a county seat war, but the massacre occurred in a strip of land which is now part of Oklahoma, the “panhandle” part. In 1888, however, it was called the “Neutral Strip” or “No Man’s Land”.

Stevens County, Kansas was established in southwest Kansas on August 3, 1885. The town of Hugo (later called Hugoton) was established in late 1885 and the town of Woodsdale was founded in 1886 by Colonel Samuel Newitt Woods. Hugoton and Woodsdale would later lock horns over which one would be the county seat. In that day, county seat wars were all too common – Gray, two counties northeast, was another that turned into an unfortunate bloody affair (you can read about it here).

Stevens County, Kansas was established in southwest Kansas on August 3, 1885. The town of Hugo (later called Hugoton) was established in late 1885 and the town of Woodsdale was founded in 1886 by Colonel Samuel Newitt Woods. Hugoton and Woodsdale would later lock horns over which one would be the county seat. In that day, county seat wars were all too common – Gray, two counties northeast, was another that turned into an unfortunate bloody affair (you can read about it here).

Colonel Woods, of course, opposed the idea of Hugoton being designated the county seat from the very beginning. Hugoton’s response to Woods’ meddling was to have him arrested on a libel charge and escort him out of Kansas into No Man’s Land. The county seat election was held and not surprisingly Hugoton won, although amidst voting irregularities.

Woods was not to be deterred, however. In 1888 a referendum was ordered by the county on the question of issuing bonds for railroad construction. Apparently Woods did some wheeling and dealing and the plans called for the rail line to pass through Woodsdale and bypass Hugoton and the citizens of Hugoton rallied to defeat the measure. The two sides accused each other of fraud and violence escalated, so much so that the Kansas militia was dispatched.

The marshal of Hugoton, Sam Robinson, had whacked Jim Gerrond of Woodsdale in the head with the butt of his revolver when the two met in Voorhees. A warrant was issued for Robinson’s arrest and turned over to Ed Short, marshal of Woodsdale, to pursue. Short went to Hugoton with the intention of arresting Robinson, but instead the two exchanged shots and Short retreated.

About a month later Short learned that Robinson had gone on a hunting trip in No Man’s Land, or as Ballots and Bullets: The Bloody County Seat Wars of Kansas put it, a “hunting, fishing, plum-picking, and picnicking excursion,” wives and children included. They reached Goff Creek on Tuesday, July 24 and set up camp. Short had passed through Voorhees on Saturday the 21st and learned of the family excursion and decided to go after Robinson.

Short returned to Woodsdale to recruit some help and on the 22nd they headed for No Man’s Land. “That he had no official jurisdiction as an officer of the law in the Neutral Strip troubled him not at all; since there was no law in No Man’s Land, both outlaws and lawmen felt free to operate as they pleased.” (Ballots and Bullets, p. 148) When Short caught up to Robinson’s group he was determined to serve the warrant but didn’t want to risk injury to the women and children. Instead he sent a cowboy from the nearby Patterson Ranch to deliver his ultimatum.

Robinson was sure that Short was bluffing so he saddled up his horse and galloped away. His friends, Charles and Orrin Cook and A.M. Donald quickly took down the camp and headed back to Stevens County to alert the town about the latest attempt on Robinson by the lawmen of Woodsdale. Word had already reached Hugoton, however. As soon as Short had departed Woodsdale with his posse a “spy” alerted the citizens of Hugoton. By Tuesday the 24th Hugoton already had assembled a party of ten to fifteen men who were already headed out to rescue their marshal.

Meanwhile, Short was in hot pursuit of Robinson, who after a brief exchange of gunfire was wounded slightly. Ed Short realized, however, that he needed more help and sent Dick Wilson back to Woodsdale. During the night Robinson escaped and later one of the Hugoton posses came upon Short and Bill Housley – Short and Housley barely escaped and in the process Short dropped his gun. Taking a circuitous route they finally arrived back in Woodsdale.

The largest posse consisting of J.B. Chamberlain, the Cook brothers, J.W. Calvert, John Jackson, John A. Rutter and William Clark found their slightly-wounded marshal. Instead of returning to Hugoton, however, they decided to go deeper into No Man’s Land seeking out anyone from Woodsdale. Meanwhile, Woodsdale’s Sheriff Cross had organized his own posse to rescue Short: Robert Hubbard, Rolland T. Wilcox, Cyrus Eaton and Herbert Tonney, heading out about nine o’clock on the evening of the 24th in a pouring rainstorm.

Cross and his posse arrived in Voorhees about four hours later and ate at an all-night restaurant. Continuing on they arrived at the Goff Creek location where Ed Short had last been seen (unbeknownst to them Short and Housley were already en route back to Woodsdale). After learning that Short was no longer in the area they spent the rest of the day looking for Short, of course unsuccessfully. As night approached, Cross and his men decided to make their way back to Stevens County.

About nine o’clock that evening (the 25th) they came upon a camp of four men who had been cutting hay around the nearby dry lake bed (Wild Horse Lake). It was a good place to stop since both they and their horses were in need of rest. While the horses grazed they moved off about fifty yards from the haymakers’ camp to eat, stretch out and sleep for awhile before continuing on. Cross, Hubbard and Tonney laid down near two haystacks while Eaton and Wilcox chose a hay wagon.

Not long afterwards Robinson and his friends surprised them and killed the sheriff and three of his deputies. After feigning death, Tonney, though seriously wounded, was able to make his way back to Voorhees. After details of the massacre became known to residents of Stevens County, the whole county was on edge and armed to the teeth. The mayor of Woodsdale implored Kansas Governor John Martin to act. Martin sent Attorney General S.B. Bradford to the scene of the crime.

Bradford observed the pools of blood where the men had been shot and verified witness statements, including Tonney’s. Bradford was also convinced that the situation was indeed volatile. When asked if there was danger of further trouble he replied, “Yes; immediate danger. If one man from either town goes to the other, he will be killed, and this will precipitate a fight. Both towns are armed and patrolled, there being about 150 armed men at each place. They have rifle pits and pickets day and night.” (Topeka State Journal, August 2, 1888)

Even though it was obvious that an act of cold-blooded murder had been committed, astonishingly no one was arrested – No Man’s Land was out of Kansas state jurisdiction. Colonel Woods, however, worked for two years to find a way to bring the murderers to justice. Twelve men from Hugoton were indicted and tried in a Federal Court in Paris, Texas. Five were convicted of murder but the United States Supreme Court ordered a new trial, which never occurred.

In June of 1891, Colonel Woods was gunned down, shot and killed from behind by Jim Brennan, a deputy sheriff of a neighboring county. Brennan, a witness for the defendants in the Federal trial, surrendered himself to authorities in Liberal, Kansas but was never tried – the reason being the jury pool of Stevens County was so contaminated with partisans of both factions that it was impossible to seat an unbiased jury.

After Woods died, Woodsdale declined; the post office closed in 1910 and the townsite was sold off for taxes. By 1934 even the remains of Sheriff Cross and his men were moved to other locations. To this day, Hugoton remains the county seat.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Tombstone Tuesday: Measles Memorial Cemetery

This cemetery was apparently a family cemetery on a plot of land owned by John W. Measles of Lavaca, Sebastian County, Arkansas since the first person buried there was John’s son Emil who died in 1891 at the age of twenty-two. How long it remained a private cemetery is unclear since there are several other people buried there who may or may not be related to the Measles family.

This cemetery was apparently a family cemetery on a plot of land owned by John W. Measles of Lavaca, Sebastian County, Arkansas since the first person buried there was John’s son Emil who died in 1891 at the age of twenty-two. How long it remained a private cemetery is unclear since there are several other people buried there who may or may not be related to the Measles family.

At the entrance is a sign which reads “Measles Memorial Public Cemetery.” The First Baptist Church of Lavaca is nearby and it appears that some of those interred in the cemetery were members of that congregation. What caught my eye, of course, was the somewhat unusual cemetery name, specifically the surname “Measles.”

After a bit of research, I’ve concluded that “Measles” was not the original spelling of this family name, nor am I certain how the name was originally spelled, although I’m leaning toward “Mizell”. As the article unfolds you’ll see the various spellings, but first some information about John W. Measles and his family.

John W. Measles

His tombstone indicates he was born in 1841 and 1850 census records show he was born in Lauderdale County, Tennessee to Miles and Elizabeth Mizells. In 1860 John was still residing with his parents, but for the census their names are spelled “Measles”. Whether or not the spelling “evolved” to “Measles” over those ten years is unclear.

On November 11, 1861, J.W. Meazles enlisted in the Confederate Army for one year service in Company E of the 1st Confederate Cavalry, recruited by Captain C.H. Conner. For the muster roll dated April 30, 1862, he was listed as absent – “captured by the enemy near Paris, Tenn. 11 March 62 with horse & equipments.”

The Paris courthouse lawn was the staging area for several Confederate units. On March 11, 1862 General Ulysses S. Grant brought the Civil War to Paris, his troops numbering five hundred while the Confederates had four hundred on that day. The two sides battled for about thirty-five minutes until the Union troops retreated back to Paris Landing. Union casualties were four killed and five wounded and the Confederates sustained twenty casualties.

The Paris courthouse lawn was the staging area for several Confederate units. On March 11, 1862 General Ulysses S. Grant brought the Civil War to Paris, his troops numbering five hundred while the Confederates had four hundred on that day. The two sides battled for about thirty-five minutes until the Union troops retreated back to Paris Landing. Union casualties were four killed and five wounded and the Confederates sustained twenty casualties.

A record dated March 12, 1864 indicates that John resigned on October 1, 1862, perhaps following his release from captivity, but apparently returning to duty soon afterwards because from October 30, 1862 to April 30, 1863 John Measley had been reassigned away from his company – “absent at wagon train.” Records indicate that John served as a teamster for the remainder of the war. He (“Jno Measels”) was mustered out “in accordance with the terms of a Military Convention entered into on the 26th day of April, 1865,” although the roll is undated. John had last been paid on November 1, 1863.

On May 29, 1867 J.W. Measells married Martha Caroline Norman in Lauderdale County. John was a farmer and by 1870 their first child Emil was two years old, born on March 18, 1868. John and Martha lived in Civil District 10 of Lauderdale County, his parents Miles and Elizabeth Mizells lived close by, according to the census six residences down the road.

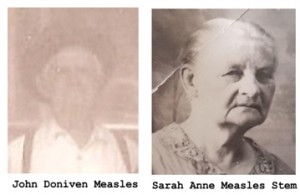

Between the 1870 and 1880 censuses the family migrated to Sebastian County, Arkansas. In 1880 J.W. and Martha Measels had four children: Emil A., Emma Dora, John Doniven and Sarah Anne. In 1884, their son Merritt Monroe was born. Emil married Lula Seward on December 19, 1888 and on January 14, 1891 he died – one family historian believes he fell from a horse. Shortly after his death, Lula discovered she was pregnant and named the baby “Emil A.” after his father. Emil was the first person buried in the cemetery located on John’s land in Lavaca.

Between the 1870 and 1880 censuses the family migrated to Sebastian County, Arkansas. In 1880 J.W. and Martha Measels had four children: Emil A., Emma Dora, John Doniven and Sarah Anne. In 1884, their son Merritt Monroe was born. Emil married Lula Seward on December 19, 1888 and on January 14, 1891 he died – one family historian believes he fell from a horse. Shortly after his death, Lula discovered she was pregnant and named the baby “Emil A.” after his father. Emil was the first person buried in the cemetery located on John’s land in Lavaca.

John and Martha Measles were enumerated in Lauderdale County, Tennessee for the 1900 census, probably visiting Martha’s eighty-two year old father F.T. [sp?] Morman [Norman]. Interestingly, a granddaughter (of Martha’s father) named Thursday (sp?) Measles is listed as well, thirty-six years old and born in October of 1863. Whose child she was is unclear since John was away serving in the Civil War at that time and he and Martha didn’t marry until 1867.

In 1910 John and Martha lived next door to Merritt in Lavaca and John was still farming at the age of sixty-nine. In 1911 Martha passed away, and according to Sebastian County death records John W. Measels died on November 14, 1914. Their daughter Emma Dora Kidd passed away on August 21, 1923 and is buried with her family in Measles Memorial Cemetery. Her husband Benjamin is buried there as are twin daughters Dorris and Dorothy who died in 1926 and 1928 respectively (born in 1925). Find-A-Grave notes that these are Emma’s children, but according to Sebastian County death records she passed away in 1923, so perhaps Benjamin remarried (he died in 1939).

John and Martha’s children John, Sarah and Merritt lived into their eighties and nineties, and with the exception of Merritt, were buried in the family cemetery (he is buried in Fort Smith). Merritt’s infant son was born and died on January 12, 1910 and buried in Measles Memorial. The spouses of Sarah and John are buried there as well, but no sign of the mysterious “Thursday Measles” from the 1900 census.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Surname Saturday: Boaz

Boaz

There are several theories about the origins and meaning of the Boaz surname. First of all, Boaz appears in scripture as a forename, the kinsman redeemer for Ruth, who later became her husband. Thus it is possible that Christians in England took Boaz as a surname at some point.

The name, with various spellings such as Boas, Boase, Bost, Boasie, may have been a name given to someone who was boastful or vain. If derived from the Old English word “bost” it would carry the meaning of “vaunt” or “brag”.

The earliest records include Walter Bost of County Oxford in 1279, Walterus dictus Bost of County Oxford in 1300, Walter Boost of County Sussex in 1327 and Richard de Boste listed on the Yorkshire Poll Tax in 1379. According to House of Names, the name was first seen in Cornwall where a family seat had been held long before the Norman Conquest of 1066.

The earliest records include Walter Bost of County Oxford in 1279, Walterus dictus Bost of County Oxford in 1300, Walter Boost of County Sussex in 1327 and Richard de Boste listed on the Yorkshire Poll Tax in 1379. According to House of Names, the name was first seen in Cornwall where a family seat had been held long before the Norman Conquest of 1066.

One of the earliest Boaz immigrants to America was Thomas Boaz. However, family historians disagree as to when he was born, when he immigrated and when he died. I’ll discuss those differences below, including a biography of the family historian, Hiram Abiff Boaz, whose research has most recently been disputed.

Thomas Boaz

Many descendants of Thomas Boaz have apparently relied heavily on the research conducted and published by family historian Bishop Hiram Abiff Boaz, entitled Thomas Boaz Family in American with Related Families.

In his research, Hiram believed that Thomas was born in Scotland on September 21, 1721, migrated to Ireland where he applied to the government for land in Virginia in 1737. He married Agnes in 1742 in Northern Ireland and in 1747 or 1748 settled in Pittsylvania County, Virginia where he owned 2800 acres. According to Hiram, Thomas and Agnes had four children before immigrating to America and he died in Pittsylvania County in 1791.

More recently, family historian Robert V. Boaz concluded from his findings (The Boaz Family: Ancestors and Descendants) that Thomas was born around 1714 in Virginia and died in 1780 in Buckingham County, Virginia. Robert believes that Thomas married Elenor Archdeacon in 1736, she having been born about 1718 in County Kilkenny, Ireland and immigrating with her parents in the 1730’s. The two historians seem to agree on the children’s names, just not entirely as to where and when they were born:

- Thomas – ca. 1737 in Goochland County, Virginia (Hiram: 1743 in Ireland)

- Archibald – ca. 1739 in Goochland (Hiram: 1744 in Ireland)

- Edmond – ca. 1741 in Goochland (Hiram: 1745 in Ireland)

- Daniel – ca. 1743 in Goochland (Hiram: 1746 in Ireland)

- Gemima – ca. 1745 in Albemarle County (Hiram: 1747 in Ireland)

- Polly – ca. 1747 in Albermarle (Hiram: 1753 in Albermarle)

- James – May 20, 1749 in Albermarle (Hiram: same)

- Shadrach – ca. 1751 in Albermarle (Hiram: same)

- Meshack – ca. 1753 in Albermarle (Hiram: 1753 in Albermarle)

- Agnes – ca. 1755 in Albermarle (Hiram: same)

- Eleanor – ca. 1757 in Albermarle (Hiram: same)

- Abednego – February 6, 1760 in Albermarle (Hiram: same)

Robert’s research seems to adequately dispute previously published research, although I didn’t have access to Hiram’s book. The most recent research findings indicate that Thomas received land grants in Goochland County at various times. Records show that Thomas deeded land to his son Thomas, Jr. in Albermarle County and kept back 500 acres for himself. When Thomas’ land became part of Buckingham County in 1761 his name appeared in the 1764 List of Tithes.

Although Thomas was too old to fight in the Revolutionary War he had been appointed Surveyor of Roads, in addition to taking the Oath of Allegiance. These two historical facts entitle his descendants to membership in the D.A.R.

Another family historian found a record of Archibald Boas being tried and acquitted for murder in April 1785 session of the General Court in Buckingham County. Whether this was Thomas’ son is not entirely clear, however.

I found it interesting that Thomas named three of his sons Shadrach, Meshack and Abednego, which reminds me of one of the most popular Tombstone Tuesday articles about Shadrack, Meshack and Abednego Pierson (triplets). In case you missed it, you can read it here.

I also wrote a Tombstone Tuesday article on another Shadrach, a Boaz, who was Thomas’ great grandson. You can read that one here.

Hiram Abiff Boaz was born on December 18, 1866 in Murray, Kentucky to parents Peter Maddox and Louisa Ann (Ryan) Boaz. The family moved to Tarrant County, Texas in 1873 where Hiram received his education. After graduating from Sam Houston Normal Institute in 1887 he taught school in Fort Worth.

At the age of twenty-three Hiram was licensed to preach and ordained in the Methodist Episcopal Church in 1891. That year he also enrolled in Southwestern University in Georgetown, Texas where he graduated with a Bachelor of Science degree in 1893 and a Master of Arts degree in 1895. He married Carrie Brown, daughter of a Methodist preacher, in 1894 and together they had three daughters.

Until 1902 he pastored churches in Fort Worth, Abilene and Dublin. In 1902, at the age of thirty-six, he was elected President of Polytechnic College (now Texas Wesleyan University), serving until 1911. While serving at Polytechnic College, Hiram and some of his fellow Methodists began to ponder the establishment of a major Methodist university, intending it to be the finest Methodist university west of the Mississippi. At that time, Southwestern University, his alma mater, was the oldest Methodist university in Texas, having been established in the 1870’s.

Hiram proposed that Southwestern be moved to Fort Worth and transformed into his vision of renowned Methodist university and located in a major metropolitan area. Southwestern and Polytechnic could be merged into a Methodist university and be located in Georgetown. The proposal was not favorable to Georgetown residents, however. With that rebuff from Southwestern and Georgetown, a new proposal led to the founding of Southern Methodist University in 1911.

The school opened its doors in the fall of 1915 with the former president of Southwestern University, Robert Hyer, serving as SMU’s first president. Although some people believed the honor of being the first president belonged to Hiram, he instead served as vice-president until 1913, in charge of raising much needed funds for the new university. By this time Polytechnic College had become Texas Wesleyan University, where he returned to serve as president.

In 1920 Hiram Boaz was elected to succeed Hyer as president of SMU. Although he served only two years in the presidency, his focus on reducing the school’s debt and building up its endowment funds was highly successful. He raised over one million dollars during his short tenure. In 1922 he was elected to the office of Methodist bishop and resigned the presidency of SMU.

His duties as bishop included church work overseas and overseeing the Arkansas and Oklahoma Conference until 1930. From 1930 until his retirement in 1938 he worked with Texas and New Mexico conferences. Even in retirement, Hiram intended to continue working to promote SMU, raising several million dollars. In 1956 a men’s dormitory, Boaz Hall, was named in his honor. The chairman of the Board of Trustees remarked at the ceremony, “If one university is ever the lengthening shadow of one man, the university would be this one and the man, Bishop Hiram A. Boaz.”

Hiram was an avid sports fan and even into his nineties attended SMU football games. In January of 1962 he died at the age of ninety-five.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!