Surname Saturday: Marple

Marple is most commonly known as an English surname and most sources agree that it was a locational name referring someone who lived near a maple tree grove. There are some mild disagreements about the specific location where the name emanated from. For instance, this article later highlights a Marple (or Marpole) from Wales.

House of Names refers to the Marple family of Cheshire who lived at the manor of Marple, while other sources believe it originated from Yorkshire. Specifically, the Internet Surname Database argues that the town of Marples in Cheshire is not linked to the Marple surname (but I suppose might be linked to the Marples surname, a spelling variation).

There were early occurrences of the name in Cheshire in the thirteenth century. According to 4Crests, the name is an Old English word, “merpel” and the earliest records show “Merphull” and “Merpel” being used in Cheshire, both without surnames.

There were early occurrences of the name in Cheshire in the thirteenth century. According to 4Crests, the name is an Old English word, “merpel” and the earliest records show “Merphull” and “Merpel” being used in Cheshire, both without surnames.

In the fourteenth century, Thomas de Mapples was listed on the Yorkshire tax roll of 1379. Still, it’s certainly possible that the Marple (or Marples) surname originated from the town in Cheshire. The first spelling of the village was recorded in 1248 as “Merpel”. Of course, there are many spelling variations, including: Marple, Marples, Marble, Marbles, Merple, Merpel, Merble, Merbles, Marpole and more.

One of the first (if not the first) Marple to come to America was David Marple who settled in Pennsylvania.

David Marple

The records for David Marple and his family are a bit sketchy, although I found one source with some interesting deductions as to his history. It appears that he was Welsh, or at least half-Welsh, probably born in Radonshire to parents Thomas and Rebecca (Jones) Marple (or Marpole because Rebecca Marpole is seen in Pennsylvania records later).

David and his wife Jane (Morgan??) were married before coming to Pennsylvania in the early eighteenth century. A group of Welsh Baptists had arrived in 1687:

By the good Providence of God, there came certaine persons out of Radonshire, in Wales, over into the Province of Pennsylvania, and settled in the township of Dublin, in the County of Philadelphia.

As was the case with so many people of faith in seventeenth century England, religious persecution compelled them to make the journey across the Atlantic. Parliament had passed a religious tolerance act in 1689, but by the end of the century the Church of England was again pressuring other faiths to conform.

In 1701 Thomas Griffith, Baptist minister, brought several other individuals with him from South Wales, although the list doesn’t include David and Jane Marple. It may be that they arrived between 1701 and 1703 because records show that Rebecca Marpole was added to the Pennepek (Pennepack) church around that time, perhaps after first attending a church in Newcastle, Delaware. Pennepack church records also indicated that David and Jane had been baptized in Wales (date unknown because entry was torn away).

One family researcher implies that Jane might have been related to Thomas Griffith somehow, she having a half-brother named Benjamin Griffith. Their research also includes a theory that possibly David and Jane were second cousins.

According to Pennsylvania and New Jersey church records, David died in Lower Dublin, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania at the age of seventy-five. He was a member of the Lower Dublin Baptist Church according to the same church record.

Many family researchers believe he is buried at the Old Pennepack Baptist Church (also known as the Lower Dublin Baptist Church). Someone has placed a grave stone there, but the church’s record of burials listed on their web site believes it’s possible the David Marple buried there is another David Marple (there appears to have been several descendants with the same name). The Old Pennepack Baptist Church has a long and storied history, founded in 1688, but where he is buried may be a mystery.

It appears that David’s descendants began to migrate away from Pennsylvania to Virginia and then to what became West Virginia. In case you missed it, this week’s Tombstone Tuesday article was about Albinus Reger Marple, who I believe is one of David’s descendants. You can read that article here.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Wild West Wednesday: Jackson Lee “Diamondfield Jack” Davis

No one seems to have a definitive history of Jackson Lee “Diamondfield Jack” Davis’ early life. Even the date and place of his birth appears to be a mystery. A cursory internet search will yield results spanning the years between 1864 and 1879 as his purported birth year. His place of birth is uncertain, but the name “Jackson Lee” would suggest Southern roots like perhaps Virginia or West Virginia.

No one seems to have a definitive history of Jackson Lee “Diamondfield Jack” Davis’ early life. Even the date and place of his birth appears to be a mystery. A cursory internet search will yield results spanning the years between 1864 and 1879 as his purported birth year. His place of birth is uncertain, but the name “Jackson Lee” would suggest Southern roots like perhaps Virginia or West Virginia.

Most historians consider him a gunslinger, famous for wearing his rifle slung across his back and carrying pistols, as many as three, either holstered or in his coat pocket and a Bowie knife strapped to his leg – he was armed to the teeth at all times. He made a name for himself in the mining camps of the west and later as an “enforcer” of sorts, working for cattlemen who were constantly battling for grassland with the sheep ranchers, a familiar saga of the 1800’s West (see more about the bloody Graham-Tewksbury feud in Arizona here).

Some have written about Davis as if he was an all-out hired gun, his only mission in life to shoot and kill sheep herders. If that was indeed true, then it’s easy to see how he was mistakenly accused and convicted of killing two sheep herders in 1896. That miscarriage of justice would become the most remarkable and memorable of his storied life.

Some have written about Davis as if he was an all-out hired gun, his only mission in life to shoot and kill sheep herders. If that was indeed true, then it’s easy to see how he was mistakenly accused and convicted of killing two sheep herders in 1896. That miscarriage of justice would become the most remarkable and memorable of his storied life.

How did he come by the nickname “Diamondfield Jack”? In the summer of 1892 Davis worked in a Silver City, Idaho silver mine. Not long afterwards, Idaho had a diamond rush and he later claimed to have discovered a diamond mine. He was known to have been a big talker, regularly embellishing his stories. After taking a job with the Sparks-Harrell Cattle Ranch and bragging about his adventures as a diamond miner, someone gave him the nickname “Diamondfield Jack” and it stuck.

In 1895 Davis was hired by James E. Bower, general superintendent of the ranch, ostensibly to bully and intimidate sheep herders in the area who were thought to be intruders on the cattlemen’s grassland. His reputation for carrying all those weapons was no doubt meant to intimidate and from time to time he included threats to kill someone.

In fact, he did carry out one of those threats by wounding Bill Tolman in the shoulder. Davis left the area for awhile until things cooled off, drifting into Nevada to avoid an warrant for his arrest for attempted murder. In late January of 1896 he ventured back into southern Idaho, later testifying that he was on his way back to turn himself into the sheriff for Tolman’s shooting.

Along the way he joined up with Fred Gleason, another cowboy employed by the Sparks-Harrell Ranch. Together they seemed to have meandered along, not in any real hurry, looking for horses. On the evening of February 2 the two were riding after dark near a sheep camp. Davis stopped and fired off a few rounds in the direction of the camp and then the two men continued on their way back to the Brown Ranch where they were staying.

The following day Davis and Gleason hung around the ranch and shoed their horses. The following morning they decided to leave and head up the river to the Middle Stack Ranch. They continued to meander their way through, again, in no particular hurry. On February 6 they met with James Bower at the H.D. Ranch and Bower rode with them to Wells, Nevada. Witnesses later testified that Davis and Gleason remained there for several days – drinking and talking too much.

Meanwhile, the bodies of sheep herders Daniel Cummings and John Wilson had been found, a grisly discovery made by a sheepherder named Ted Severe at Deep Creek. The crime scene was littered with .44 caliber bullets shot from a .45 caliber gun. It was known that Davis had a reputation for using .44 caliber bullets when he couldn’t find the exact caliber for his weapons of choice. Thus, he became the prime suspect in the murders.

Another cowboy with the Sparks-Harrell operation later testified that Davis had decided to leave the country and head south – his friend Gleason was drunk all the time and threatening to kill sheep herders in Deep Creek. Until he was arrested in March of 1897 in Yuma, Arizona for his alleged crime, no one knew of his whereabouts. Because Davis and Gleason had been in the area of the killings and Davis had the reputation of bullying and intimidation, the locals just assumed Davis was guilty.

Adding to the assumption of his guilt, Davis was arrested while jailed in the Yuma Arizona Territorial Prison. Gleason had been found in Deer Lodge, Montana. By mid-March the two were brought to Albion, Idaho to stand trial. The sheep herders and their supporters, including the Wool Growers Association, mounted an all-out effort to see them convicted. Davis and Gleason, however, had the cattlemen on their side. John Sparks and Andrew Harrell, former employers, put up most of the funds for their defense.

Davis and Gleason had the best defense lawyers money could buy and testimony and evidence was carefully and methodically presented. The prosecutors were also well-qualified and able to establish that the two men had at least been in the area of the crime on that day. When it came time to decide Davis’ fate, the jury took only two hours to find him guilty of first degree murder. He was sentenced to hang on June 4, 1897. Gleason’s trial, however, had a different result – he was acquitted.

The next five years of Jack Davis’ life turned out to be most harrowing. Appeals were mounted by his attorneys and several times his execution was stayed. At one point he was transferred to the Idaho State Penitentiary, only be to returned to the Cassia County Jail where he had first been imprisoned during and following his trial.

Following another series of appeals, another execution date was set for July 3, 1901. This must have been frustrating for Davis and his attorneys, for you see two other men, James Bower and Jeff Gray had finally confessed to the killings, claiming self-defense. Davis received a short reprieve from the Board of Pardons with a new date of execution scheduled for July 17. His attorneys had been unable to convince the Board of his total innocence, even with the knowledge of Bower and Gray’s confession.

Three hours before his scheduled execution on the 17th, his sentence was changed to life imprisonment – no exoneration yet, but Davis would be allowed to live out his life in the Idaho State Penitentiary. After another round of legal wrangling and appeals, Jackson Lee “Diamondfield Jack” Davis was finally pardoned by Idaho Governor Frank Hunt on December 17, 1902.

His case had been covered by newspapers all around the country. When released, Davis unsurprisingly left Idaho and moved to Nevada. He kept his name and reputation in the papers over the ensuing decades, striking it rich in the mining camps of Nevada. He later wrangled with the Industrial Workers of the World and continued to carry four guns with him at all times. When asked why he did that, Davis replied, “Well, if I ever get into a mix-up and don’t have my guns and got killed, I’d never forgive myself as long as I lived.”

By the late 1930’s Davis, then in his seventies, was still seeking more fortune. He made his way to Las Vegas and for several years afterwards alternated between residences in Los Angeles and Las Vegas. The man who seemed to have nine lives (or more), finally met his end not in a spectacular fashion befitting his gunslinger image, but in an accident with a taxi cab after stepping off a curb in Las Vegas on December 28, 1948.

While on the way to the hospital, he told a friend that he intended to live to the age of one hundred. Jack Davis lingered for a few days but passed away on the morning of January 2, 1949. One obituary printed in a Salt Lake City newspaper was full of misstatements about his life, and was probably picked up by other papers across the country.

But, that was the story of his life apparently, largely misunderstood and misreported. As Max Black pointed out in his book entitled Diamondfield, the irony of the incorrect obituary was perhaps fitting, for Davis himself was known to be an exaggerator of the truth.

Diamondfield Jack was definitely a “Wild West” character and a part of Idaho folklore and history. A National Forest campground is named in his honor, as well as a restaurant in Twin Falls, Idaho.

If you’re interested in learning more details about Diamondfield Jack and his legal entanglements and woes, followed by his successful business career, Max Black’s book was written to finally tell the truth about what really happened. The book is available on Amazon for $3.99, and if you have Kindle Unlimited, it is free to borrow.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Tombstone Tuesday: Albinus Reger Marple

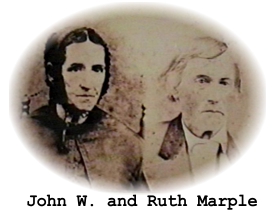

Albinus Reger Marple was born on January 27, 1834 in Lewis County, Virginia to parents John Weaver and Ruth (Reger) Marple. It’s possible that his first name was a family name, evidenced by a record of someone named Albanus Marple in Pennsylvania. Most family researchers believe that Albinus’ grandfather John Abram Marple was the son of Enoch Marple, Sr. of Philadelphia, who later migrated to Virginia. His middle name, of course, was his mother’s maiden name.

Albinus Reger Marple was born on January 27, 1834 in Lewis County, Virginia to parents John Weaver and Ruth (Reger) Marple. It’s possible that his first name was a family name, evidenced by a record of someone named Albanus Marple in Pennsylvania. Most family researchers believe that Albinus’ grandfather John Abram Marple was the son of Enoch Marple, Sr. of Philadelphia, who later migrated to Virginia. His middle name, of course, was his mother’s maiden name.

Research revealed more than one spelling of his name, but it is spelled “Albinus” on his grave stone, with alternate spellings on various records of Albinos, Albinas and Albenus. Albinus married Mary Jane Post, daughter of Daniel and Mary Post on February 1, 1855 in Upshur County, Virginia (eventually West Virginia). The children (rather unusually named) born to their marriage were:

Research revealed more than one spelling of his name, but it is spelled “Albinus” on his grave stone, with alternate spellings on various records of Albinos, Albinas and Albenus. Albinus married Mary Jane Post, daughter of Daniel and Mary Post on February 1, 1855 in Upshur County, Virginia (eventually West Virginia). The children (rather unusually named) born to their marriage were:

Mandema “Dem” (1856)

Louvernia “Vernie” (ca. 1859)

Seleucus “Luke” Eumenis (1860)

Nevada “Vadie” (1866)

Achilles Landolus “Dolus” (1872)

In 1860 Albinus and his family were enumerated in Buckhannon (Upshur County). At that time Upshur County was still part of Virginia. However, when Virginia voted to secede from the Union in April of 1861, the delegates west of the Allegheny Mountains opposed the move.

On May 15, 1861 the anti-secessionists of western Virginia convened their own convention in Wheeling and began to make plans for their own state in support of the Union. On June 20, 1863 Congress granted statehood to West Virginia.

However, during the Civil War, the state was considered a border state like Delaware, Maryland, Kentucky and Missouri. Apparently, Albinus and his brother Addison were sympathetic to the Confederate cause, at least at the war’s beginning. Both deserted the Rebel Army shortly after enlistment and both surrendered to private citizen Joseph Strager, as noted in an article entitled Men In Gray: Confederate Soldiers of Central West Virginia by Ralph P. Bennett.

However, during the Civil War, the state was considered a border state like Delaware, Maryland, Kentucky and Missouri. Apparently, Albinus and his brother Addison were sympathetic to the Confederate cause, at least at the war’s beginning. Both deserted the Rebel Army shortly after enlistment and both surrendered to private citizen Joseph Strager, as noted in an article entitled Men In Gray: Confederate Soldiers of Central West Virginia by Ralph P. Bennett.

On October 19, 1863, the brothers took an oath of allegiance to the Union and were sent north. According to Bennett, it was common for the Union to send former Confederate soldiers north of the Ohio River. Bennett further described the predicament Albinus and Addison, much like other former Confederate soldiers, faced:

The Marple brothers like many others wished to serve the cause of the Confederacy, yet their loyalty was in conflict with their awareness of the sufferings and privations of their families who lived behind enemy lines. A letter in the 31st Virginia Infantry by John M. Ashcraft, from the wife of Private William W. Stockwell to her soldier husband states , having hard time out of provisions, no crops, will come to you, meat [sic] me at Staunton. Many soldiers requested detached duty to spy on Union activities and hopefully recruit soldiers but often their primary motivation was to visit home and family. By 1864 the declining fortunes of the Confederacy caused morale to plummet and desertions increased markedly.

Albinus and his brother survived the war and returned to Upshur County to farm. A short biography of Albinus was included in The History of Upshur County, West Virginia, published in 1907. At that time he owned three hundred and eighty acres of fertile land along Hackers Creek. Albinus and Mary Jane were members of the Westfall Chapel Methodist Protestant Church.

Albinus died on September 9, 1908 and a few months later on January 20, 1909 Mary Jane passed away. Both are buried in the McVaney Cemetery in Upshur County.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Tombstone Tuesday: Jesse J. Bird

Jesse J. Bird was born in Patrick County, Virginia on June 2, 1831 to parents Benjamin and Lucy (Grady) Bird. Benjamin served for about six months during the War of 1812 in Virginia’s militia, as evidenced by a pension application submitted by Lucy. Benjamin died in 1837 when Jesse was about six years old.

Jesse J. Bird was born in Patrick County, Virginia on June 2, 1831 to parents Benjamin and Lucy (Grady) Bird. Benjamin served for about six months during the War of 1812 in Virginia’s militia, as evidenced by a pension application submitted by Lucy. Benjamin died in 1837 when Jesse was about six years old.

Jesse, the oldest child, struck out on his own at the age of nineteen. In 1860 he was working as a farm laborer in the St. Mary’s Township of Hancock County, Illinois. In 1864 he left Illinois after hearing about gold discovered in Montana the year before.

After arriving in Virginia City he had no problems securing employment. According to An Illustrated History of the State of Montana, Jesse worked to install water works in the town, earning one hundred dollars a month. After finishing that work, he worked in the mines and prospected.

After arriving in Virginia City he had no problems securing employment. According to An Illustrated History of the State of Montana, Jesse worked to install water works in the town, earning one hundred dollars a month. After finishing that work, he worked in the mines and prospected.

After giving up mining, Jesse purchased a ranch near Virginia City. In 1873 after working the ranch for three years he sold it and settled on one hundred and thirty acres of land, remaining there the rest of his life. He apparently had never taken a wife until in 1878 he married Elizabeth Morgan, a Canadian. Census records indicate they had one child together, Franklin, born in either 1878 or 1879. Elizabeth died on September 7, 1885 and most family researchers believe Franklin died sometime that year as well.

When Jesse left Virginia, his family, mother Lucy and his other siblings, remained there. His sister Charity Ann remained with her mother and in 1880 she still lived with Lucy who was the seventy-two years old. When or why they migrated to Montana isn’t known, but on October 3, 1895 Lucy died in Montana at the age of ninety-five.

Charity, five years younger than Jesse, continued to live with him and was his housekeeper. She passed away in 1901. In 1910 Jesse was still enumerated as a farmer at the age of seventy-eight and his nephew (probably great-nephew) Ralph Bird, aged fifteen, was living with him. By 1920, Ralph was still single, had a housekeeper and hired man and owned the farm. Jesse died on January 11, 1920 and the census was taken in April, so it’s possible that Ralph inherited the farm from Jesse since his only son had died at a young age.

According to the Montana history source cited above, Jesse Bird was one of “Montana’s worthy pioneers”. Politically he was said to have first been a Whig, a political party later merged into the National Republican Party. Following the collapse of the Whig Party, Jesse became a Democrat and then a Populist. Jesse was a good man, maintaining a “good and worthy character, and by those who [knew] him best he [was] most highly respected.”

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Surname Saturday: Pray

Like the Thing surname (see article here), the Pray surname is a bit hard to research because it is such a common word. Added to that are the various theories as to origins, three at least, and none of them have anything to do with the most common way we use the word “pray” today. The theories are:

House of Names: Actually House of Names has both an English and Irish theory. In England the name may have been derived from the Latin word “praetor”, which meant someone who served as chief magistrate or bailiff of a district. Spelling variations might include Prater, Prather, Preater, Pretor, Prether and more. In Ireland the name may have been “Preith” or “O Preith” with origins from a Pictish (ancient language that no longer exists) word “predhae”. Irish spelling variations include O’Pray, O’Prey, Prey, Preay and others.

Ancestry.com: The Irish version may have been a variant of “Prey”. The English version may have been a topographic name for someone who lived near a meadow, derived from the Middle English word “pre(y)”. The word could also have originated in France, and brought over following the Norman Conquest, because “pree” in Old French means meadow as well.

4Crests: Their theory leans heavily on French origins, also agreeing that the name was topographic for someone living near a meadow. Derived from the Old French word “pred” with origins in the Latin word “prata”, this theory supports spelling variations different from those listed above, including: Pree, Prey, LaPraye, Dupre, Depuy, Despres and Prada. The French name “Duprè” means “from the meadow”. This theory makes me wonder if one of my ancestors, Francis Dupee, was of French descent.

Early American Prays

Quentin (or Quinton) Pray was born in England in 1595, and with his family boarded the “good ship Ann Cleeve of London” in May of 1643. On the same boat was John Winthrop, Jr., son of the founding governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, John Winthrop. Winthrop’s plan was to establish an iron works in Massachusetts.

Quentin, a skilled iron worker, settled first in Kittery, Maine, while his sons John and Richard settled in Rhode Island. He worked at the iron works in Kittery as a fineryman, later transferring to Lynn, Massachusetts in 1647 and finally transferring to the Iron Works Company, established by Winthrop in Braintree where Winthrop.

Quentin, a skilled iron worker, settled first in Kittery, Maine, while his sons John and Richard settled in Rhode Island. He worked at the iron works in Kittery as a fineryman, later transferring to Lynn, Massachusetts in 1647 and finally transferring to the Iron Works Company, established by Winthrop in Braintree where Winthrop.

Quentin Pray died intestate on July 11, 1667. His wife Joan was declared his widow by the court so that his estate could be distributed among his heirs. Richard remained in Providence, but John died in Braintree in 1676.

Musings on the Pray Name

Associating the surname Pray with its more common meaning today, I found at least one that seemed appropriately paired: Alice Church Pray of Kennebec County, Maine. Deacon Benjamin Pray lived in New Hampshire and his second wife was Dorcas (a biblical name) Pray (Dorcas Pray Pray, probably cousins). Two more biblical names: Zerubbabel Pray (Kennebec County, Maine) and Eliphalet Pray (York County, Maine).

One unusual name I came across that I want to research further was Pardon Potter Pray of Providence County, Rhode Island. His English immigrant ancestor was perhaps John Pray, Quentin’s son. One other aspect I found interesting while researching Pardon Potter Pray was finding that Rhode Island, and specifically Providence County, was full of men named “Pardon”. There must be a story there and you may find it here one day!

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Mothers of Invention: Ruth Graves Wakefield (Toll House Cookies)

Have you noticed it’s almost Thanksgiving, which means Christmas is just around the corner, which means the baking season is upon us. All of which usually makes me start thinking of what kind of outrageous chocolate chip cookies I’ll bake this year! So a little history is in order today – who invented the chocolate chip cookie anyway?

Have you noticed it’s almost Thanksgiving, which means Christmas is just around the corner, which means the baking season is upon us. All of which usually makes me start thinking of what kind of outrageous chocolate chip cookies I’ll bake this year! So a little history is in order today – who invented the chocolate chip cookie anyway?

Ruth Graves Wakefield was responsible for this so-called “accidental” invention. She was born on June 7, 1903 to parents Fred and Helen Graves in East Walpole, Massachusetts. In 1924 Ruth graduated from Framingham State Normal School (now Framingham State University) with a degree in household arts.

Ruth Graves Wakefield was responsible for this so-called “accidental” invention. She was born on June 7, 1903 to parents Fred and Helen Graves in East Walpole, Massachusetts. In 1924 Ruth graduated from Framingham State Normal School (now Framingham State University) with a degree in household arts.

With her degree she taught home economics at Brockton High School for two years before marrying Kenneth Donald Wakefield in June of 1926. Between the years of 1926 and 1930, Ruth worked as a dietician and food lecturer and the couple had two children, Kenneth and Mary Jane. In 1930, in the middle of the Great Depression, Kenneth and Ruth purchased a building which had originally been a toll house in Plymouth County, Massachusetts.

The house was built in 1709 and originally used as a sort of way station for travelers, a place for a change of horses and a respite for travelers, who enjoyed a meal while the horses were changed and the road tolls paid. In keeping with its original purpose, Kenneth and Ruth restored it and named it the Toll House Inn, furnished in classic colonial styles. Still, it was a risky proposition given the economic situation, and after purchasing and remodeling it the Wakefields had only about fifty dollars left to work with.

The house was built in 1709 and originally used as a sort of way station for travelers, a place for a change of horses and a respite for travelers, who enjoyed a meal while the horses were changed and the road tolls paid. In keeping with its original purpose, Kenneth and Ruth restored it and named it the Toll House Inn, furnished in classic colonial styles. Still, it was a risky proposition given the economic situation, and after purchasing and remodeling it the Wakefields had only about fifty dollars left to work with.

The operation was so small that, according to The Great American Chocolate Chip Cookie Book: Scrumptious Recipes & Fabled History From Toll House to Cookie Cake Pie by Carolyn Wyman: “When more than one of the seven tables were taken, salad plates from their limited supply of dishware would be whisked away from one table only to reappear a few moments later freshly washed and bearing dessert at another.”

The beginnings may have been shaky, but by Christmas they needed several employees to assist them. The inn seemed to be in perpetual remodeling mode as they added to it over the years. The inn became a popular destination, especially for large events, and Senator John F. Kennedy and his father were patrons as well as celebrities like Joe DiMaggio, Gloria Swanson, Betty Davis and more.

Ruth’s lobster dishes were what first made her famous, and she had a large collection of New England recipes which she inherited from her grandmother, along with her own recipe creations. Every January the Wakefields took a vacation overseas and Ruth always came back with new recipes to try. She seemed to have a knack for knowing just how to make it from scratch on her own.

Her first (small) cookbook, Toll House Recipes Tried and True, was first published in 1931 and reprinted twenty-eight times until by 1954 it had grown into a book with over eight hundred recipes. Her desserts were particularly well-known and service superb as guests were often greeted personally by the Wakefields. Ruth became famous for her Toll House cookie recipe, but truly the woman was a dessert-genius. Her Indian pudding was lauded by none other than Duncan Hines – in 1947 he proclaimed it one of his favorites.

The “accidental” story claims that she was making a recipe of Butter Drop Do cookies and wanted to add chocolate. Another story said she was missing nuts and decided to add the chocolate pieces. With no bakers chocolate on hand she decided to chop up a semi-sweet chocolate bar in pieces instead. At least one version of the story goes that she assumed that after stirring the chocolate pieces into the dough, the two would somehow melt together and make the cookie chocolate. But, instead of melting, the pieces came out as bits of chocolate scattered in each cookie, and she first called them Toll House Crunch Cookies.

However, the restaurant promoted itself as a military machine or factory production line, geared to smooth-running cohesion, as Wyman pointed out. “Long-range planning and constantly studied personnel are reflected in an operating teamwork flawless in its unruffled perfection. Confusion is unknown.”

So, as Wyman noted, it seems unlikely that Ruth would not have all needed ingredients on hand, and she thought the whole “substitute chocolate for nuts” story was preposterous. One story told by an employee over the years had its own flair. George Boucher would tell how one day he heard vibrations from the mixer which caused chocolate stored on a shelf above it to fall into the dough.

It wasn’t until the 1970’s when Ruth finally explained what had really happened. For years the restaurant had served a thin butterscotch nut cookie with ice cream. Her customers loved them and she wanted to try something different, so she devised the Toll House cookie recipe, working on it while returning from a trip to Egypt.

Another point Wyman made was that the story about Ruth thinking the chunked chocolate would melt into the cookie dough was unlikely given her background in culinary arts and a household arts degree. She had studied food chemistry and knew chocolate chunks would not melt into the cookie making it chocolate through and through. Instead, Ruth and her pastry chef Sue Brides worked together to create a new cookie to serve with ice cream.

Ruth had, of course, used Nestlé chocolate in her recipe. While several chocolate companies wanted her to endorse their products, Ruth stuck with Nestlé, and on March 20, 1939 gave the recipe to them for one dollar. The recipe was changed over the years by Nestlé, but what a stroke of luck for them, eh?

If you search the internet you will find all the “accidental” stories in one form or another. In truth, I almost fell for them too, but they were beginning to be a bit confusing and convoluted. So, I kept searching and stumbled upon Wyman’s book, an obviously well-researched and thoughtful book (although I only read a synopsis in Google Books). I find this so often whether I’m researching an article for the blog or genealogy — you just have to keep digging until you find the truth!

So, the moral to the story is you just can’t believe everything you read on the internet … but you probably (hopefully) already knew that. Happy baking season!

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Surname Saturday: Folger

This surname is interesting to me because as I began to research it I discovered that one of its spelling variations is the same as some of my ancestors (Fulcher). I would have never made the connection, but I will soon be researching that further.

The Folger surname is believed to be of Germanic origin and probably first seen in England when William the Conqueror and his forces crossed the English Channel. The spelling at that time might have been slightly different as “Foulger” or “Fulcher” (or “Fulchar”). The theory about those bearing the surname is plausible since Fulcher/Fulchar broken down translates as “Folk” (people) and “Hari” (army), or “people’s army”.

Spelling variations include: Fulcher, Foulger, Folger, Fulker, Folker, Futcher, Fuge, Fudge, Fullager and many more. The name first appeared in Lincolnshire and Derbyshire around the time of William the Conqueror. According to House of Names, “the Fulchers were known as the Champions of Burgundy and records were found of the name spelt Fulchere in Normandy (1180-1195). They also note that the Folger surname could have been derived from an Anglo-Saxon word “folgere” which means a free man who attended someone else.

Spelling variations include: Fulcher, Foulger, Folger, Fulker, Folker, Futcher, Fuge, Fudge, Fullager and many more. The name first appeared in Lincolnshire and Derbyshire around the time of William the Conqueror. According to House of Names, “the Fulchers were known as the Champions of Burgundy and records were found of the name spelt Fulchere in Normandy (1180-1195). They also note that the Folger surname could have been derived from an Anglo-Saxon word “folgere” which means a free man who attended someone else.

The Folger name is, of course, synonymous with “the best part of waking’ up is Folgers in your cup”™. First though, a little about the earliest Folgers to come to America. John Folger and his son Peter immigrated to America, landing in Boston and eventually settled on Nantucket Island. Peter was also the grandfather of one of the most famous Americans, Benjamin Franklin.

Peter Folger

Peter Folger was born in 1617 in England to parents John and Meribah (Gibbs) Folger and his family came to America around 1635, first settling around Watertown, Massachusetts. In 1644 Peter married Mary Morrell (or Morrill). Peter may have attended university before immigrating because he was skilled in mathematical sciences, working as a surveyor of both Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket.

At one point Peter became a Baptist and after moving to Nantucket was said to have evangelized the local Indians and performed baptisms, assisting Reverend Thomas Mayhew. Peter and Mary had several children: Joanna, Bethiah, Dorcas, Eleazar, Bethsheba, Patience, John, Experience and Abiah (Benjamin Franklin’s mother).

As Nantucket was in the beginning stages of settlement, five persons were chosen to survey it, Peter being one. For his services apparently he was granted a half share of land in July 1663, provided he came to live there within a year with his family and agree to serve as interpreter with the Indians. Peter agreed and spent the rest of his life on Nantucket, immersing himself in the civic affairs of his community.

In addition to his mission work with the Indians, he also served as clerk of courts for several years. Peter made his mark, garnering recognition from Cotton Mather, who believed him to be a learned and pious person. A poem Peter wrote and published in 1675/1676 was included in his grandson’s autobiography, entitled A Looking Glass for the Times, or the Former Spirit of New England Revived in this Generation. He may have established himself as one of the first to advocate freedom of religious belief for all, be they Quakers, Catholics, Anabaptists or Puritans.

James Athearn Folger

James Athearn (J.A.) Folger was descended from Peter Folger through his son Eleazar, and was born on June 17, 1835 to parents Samuel Brown and Nancy Hill Folger. Samuel was a master blacksmith who invested in the manufacture of tryworks, a trywork being the most prominent feature located aft of the fore-mast on a whaling ship, and also purchased two ships.

In 1846 a fire destroyed the family business and eleven year-old James helped his family rebuild. In 1849 gold fever gripped the nation and fourteen year-old James set out with his older brothers Henry and Edward that fall to seek out their fortunes in California. They boarded a ship for Panama, hiked across the Isthmus and caught a ship to California on the other side, arriving on May 8, 1850.

By the time the three Folger young men arrived, there wasn’t enough money left to allow all three to travel from San Francisco to the gold mining towns. James remained in San Francisco to earn his way to the mines while his brothers proceeded without him.

By the time the three Folger young men arrived, there wasn’t enough money left to allow all three to travel from San Francisco to the gold mining towns. James remained in San Francisco to earn his way to the mines while his brothers proceeded without him.

Commercially roasted coffee had been around since the beginning of the nineteenth century, but considered a luxury by most. Ground coffee had not even been conceived of yet. That would soon change, however, when William H. Bovee hired James to erect the first mill in San Francisco to produce ground coffee, The Pioneer Steam Coffee and Spice Mills.

James worked for Bovee for almost a year before he saved enough to join his brothers. He agreed to also take samples of coffee and spices and take orders from general stores throughout mining country.

When James returned to San Francisco in 1865, he had apparently succeeded well enough to become a full partner of Pioneer. In 1872 he bought out his partners and renamed his company J.A. Folger & Co. In 1861 he married Eleanor Laughran and together they had four children.

After James became the sole owner his focus turned to producing bulk-roasted coffee which was delivered in drums and sacks to stores. His son James, Jr. worked in the family business and took over after his father died on June 26, 1889.

I’ve been conducting research for a friend this year (see my articles here and here) and found she was related to a host of famous families who all lived on Nantucket, including the Folgers, Macys, Bunkers, Coffins and Starbucks. With this new insight on the origins of the Folger name and its possible roots in the German name Fulcher, I’m excited to see if perhaps I might have a connection to the Folgers further down the line. Stay tuned . . . if perchance I find out someday I’m also related to Benjamin Franklin, you’ll definitely hear about it here!

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Feisty Females: Mary Ann Bickerdyke (Part One)

General William Tecumseh Sherman declared at one point during the Civil War that she outranked him. She was not a push-over and wasn’t about to be pushed aside by Army regulations either. The Union soldiers she tended called her “Mother Bickerdyke” and they cheered her presence as they would their commanding generals.

General William Tecumseh Sherman declared at one point during the Civil War that she outranked him. She was not a push-over and wasn’t about to be pushed aside by Army regulations either. The Union soldiers she tended called her “Mother Bickerdyke” and they cheered her presence as they would their commanding generals.

She was born Mary Ann Ball on July 19, 1817 in Knox County, Ohio to parents Hiram and Annie Rodgers Ball. Annie died when Mary Ann was about seventeen months old, so Mary Ann was sent to live with her mother’s parents until Hiram remarried a few years later. Mary Ann, however, decided she preferred to live with her Rodgers grandparents.

This article is no longer available on this web site. It will, however, be published (complete with footnotes and sources) in a future issue of Digging History Magazine.

This article is no longer available on this web site. It will, however, be published (complete with footnotes and sources) in a future issue of Digging History Magazine.

I invite you to check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Tombstone Tuesday: Joseph Oklahombi

His name literally meant “man-killer” or “people-killer” in Choctaw – and even today he is still considered the most heroic Oklahoman who served in World War I. As one web site put it, Joseph Oklahombi was a “Choctaw, Doughboy, Code Talker and Mighty Warrior.”

His name literally meant “man-killer” or “people-killer” in Choctaw – and even today he is still considered the most heroic Oklahoman who served in World War I. As one web site put it, Joseph Oklahombi was a “Choctaw, Doughboy, Code Talker and Mighty Warrior.”

Joseph Oklahombi, a full-blood Choctaw, was born on May 1, 1894 (or 1895) in the Kiamichi Mountains of McCurtain County, Oklahoma Indian Territory. He married Agnes Watkins and they had at least one child, Jonah. The book Comanche Code Talkers of World War II, states that Joseph, an orphan, was underage and lied about his age. Not sure about that because if he was born in 1894 or 1895 he would have been over twenty-one years old in 1917 — hardly underage.

It is implied on his World War I draft registration record that perhaps Joseph and Agnes hadn’t been married long and had no children yet because the reason he gave for exemption from service was “support of wife”. A bit of puzzlement, however, as his registration record says that he was a “Farmer (in Jail)”.

Joseph and Agnes lived in a remote area with few neighbors, and according to the Choctaw Code Talkers Association, Joseph walked from his home to Idabel, county seat of McCurtain County, to enlist. I couldn’t find any official records as to when he actually entered the service, but he joined hundreds of Native Americans, who although not yet citizens of the United States at the time, volunteered to go overseas and fight the Germans. As the Texas Military Forces Museum web site described it, Choctaw warriors were faithful to serve along American soldiers, “fulfilling a prophecy by Pushmataha, a Choctaw chief who died in 1827, that the Choctaw ‘War Cry’ would be heard in many foreign lands.”

Joseph and Agnes lived in a remote area with few neighbors, and according to the Choctaw Code Talkers Association, Joseph walked from his home to Idabel, county seat of McCurtain County, to enlist. I couldn’t find any official records as to when he actually entered the service, but he joined hundreds of Native Americans, who although not yet citizens of the United States at the time, volunteered to go overseas and fight the Germans. As the Texas Military Forces Museum web site described it, Choctaw warriors were faithful to serve along American soldiers, “fulfilling a prophecy by Pushmataha, a Choctaw chief who died in 1827, that the Choctaw ‘War Cry’ would be heard in many foreign lands.”

Private Joseph Oklahombi joined the army and was assigned to the Thirty-Sixth Division, Company D, 141st Infantry, probably sent to Europe following training sometime in the spring of 1918. In October 1918 several Choctaw soldiers (including Joseph), in both the 141st and 142nd, were called upon to send and translate messages in their native tongue to thwart the Germans who had already broken radio codes several times. According to The American Army and the First World War, the Choctaw language had no words for such terms as “machine gun” and “casualties”, so instead they used phrases like “little gun shoot fast” and “scalp”.

On October 8, Joseph and twenty-three fellow soldiers who had been cut off from the rest of their company came upon a large group of Germans (a machine gun placement). Joseph is said to have crossed “No Mans Land” several times going back and forth with coded messages and assisting the wounded.

At one point he went about two hundred yards in the open against artillery and machine gun fire. After rushing one of the German gun nests, he seized the machine gun and began firing on the enemy. The Americans held the enemy at bay for four days and captured one hundred and seventy-one Germans. For his acts of bravery, Joseph was awarded the Silver Cross by General Pershing and the Croix de Guerre by the French.

Oklahombi was a skilled marksman, believed to have killed the enemy by the dozens according to several accounts. One day he had come upon a group of Germans pausing for a meal and resting in a cemetery that was surrounded by high walls and a gate. Joseph covered the gate with intense fire and may have killed as many as seventy-nine.

After returning home from the war, Joseph went back to his life as a farmer. He didn’t talk much about his war experiences, but as the world again began assembling for war again in the late 1930’s and early 1940’s, he was prepared to serve again if necessary.

By that time Joseph was in his mid-forties and son Jonah was working with the Civilian Conservation Corps in Idabel. He followed world events and in October of 1940 was quoted as saying, “The United States must prepare and do it immediately.” He believed “the European war is more horrible than the World war.” He added that he wasn’t in favor of war, “but if the peace of the United States is molested, we must be prepared to defend ourselves.”

By that time Joseph was in his mid-forties and son Jonah was working with the Civilian Conservation Corps in Idabel. He followed world events and in October of 1940 was quoted as saying, “The United States must prepare and do it immediately.” He believed “the European war is more horrible than the World war.” He added that he wasn’t in favor of war, “but if the peace of the United States is molested, we must be prepared to defend ourselves.”

As all men of a certain age were required at that time Joseph registered for the draft in 1942, but never called to serve. He was said to have been reluctant to talk about his war experiences, at one point deciding he would no longer speak English. When honored at a public reception at Southeastern State College, he only spoke in his native Choctaw language. At one point he was offered a Hollywood movie role, turning it down because he refused to leave his home in Oklahoma.

According to the Miami (OK) Daily News-Record, Joseph applied for a pension but wasn’t successful in receiving one until 1933 when he received twelve dollars a month. After the pension was terminated, Joseph was left destitute and appealed for help in 1937. A newspaper article about his plight brought job offers and he took one at a Wright City lumber company. His fellow Choctaw tribesman often honored him at their tribal dances and celebrations.

Sadly, Joseph Oklahombi was struck and killed by a truck while walking along a road on April 13, 1960. The man driving the panel truck was charged with manslaughter. Joseph Oklahombi was buried with military honors in Yashau Cemetery near Broken Bow, Oklahoma. His name appears with his fellow Choctaw Code Talkers at the Choctaw War Memorial in Tuskahoma, Pushmataha County, Oklahoma.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Surname Saturday: Thing

This surname was a bit of a challenge to research. The word “Thing” is so commonly used today, even in a slangy-sort-of way, it’s definitely hard to find a way for a search engine to yield the desired results. But there is at least one interesting theory as to the origins of this somewhat unusual surname.

It is believed to have been a medieval surname, dating back hundreds of years, and could have been a nickname for a slender or lean person, according to the Internet Surname Database. The name may have derived from an Olde English word “thynne” which could have also referred to a location, a village in East Yorkshire by the name of “Thwing” and literally meaning “long and thin.” A spelling variation related to that theory may have been “Thying”.

House of Names had the most interesting theory, however, because they believe it derives from a name which is not even close in spelling or pronunciation. Their theory is that the name was originally “Botfield” or “Botville”, introduced in England when two men named Geoffrey and Oliver Bouteville arrived from France around 1180.

From their lineage came a man named “John Boteville” who counseled at Lincoln’s Inn and was referred to as “John of th’Inn”. House of Names admits, however, that the name could just have well arisen out of intermarriage between the Botville and Thynne families.

From their lineage came a man named “John Boteville” who counseled at Lincoln’s Inn and was referred to as “John of th’Inn”. House of Names admits, however, that the name could just have well arisen out of intermarriage between the Botville and Thynne families.

If that’s the case, then there are several unusual spelling variations, including: Botfield, Botville, Boteville, Botfeld, Botevile, Thynne, Tyne, Tine, Tynes, O’Tyne, Thinn, O’Thinn, Thin, Then, Them and many others. (House of Names)

Early Things in America

One of the earliest Things to come to America was Jonathan Thing, born in 1621. It does get a little confusing, though, because there were several people with that exact name, at least two of them with the rank of Captain. Another Captain Jonathan Thing appears to have been born around 1654 and died in 1694, supposedly by a self-inflicted gunshot as he was falling from his horse. Those two Jonathan Things may have been father and son as both appear to have lived in Rockingham County, New Hampshire.

There seems to have been a concentrated population of Things in both Maine and New Hampshire, and perhaps a few of the Things intermarried with some of the historic Nantucket families. For instance, Abigail Coffin married Bartholomew Thing. For more on the Coffin surname and history you can read an article here.

Unusually Named Things

Just browsing through Find-A-Grave entries, I saw some unusual Thing names. For instance, Blanche Arlene Thyng Thing was born in 1896 and died at the age of one hundred in 1996. She is buried in York County, Maine. Her father William Thyng married Georgia Coffin (some of the Coffins migrated to Maine from Nantucket). Blanche’s husband was Ralph Shepley Thing.

Ralph’s parents were Ether and Adelaide Thing. Apparently someone transcribed Ether and Adelaide’s marriage record incorrectly and he is referred to as Esther S. Thing quite often. The official Massachusetts marriage record clearly spells his name “Ether” and the Methodist Church record sort of looks like “Esther”. Nevertheless, I’m betting Blanche and Ralph were perhaps distant cousins, each with a slight variation in the spelling of their surname.

Datus Thing was born in Maine in 1847 and died at the age of seventeen. Converse M. Thing was born in Maine in 1834. Hannah Thing Thing, another likely cousin marriage, was born in York County, Maine in 1805. A couple of “royal names” I ran across: King David Thing who was born in York County, Maine in 1858 and Prince Thing born around 1853 in Maine. These two “royals” were probably cousins because they don’t appear together in the same family on the 1860 census records.

Sad Things

Prince may have been the son of the last Thing I’ll mention – Levi, born around 1807 in Maine – since the name appears on the 1860 census, right above his brother “No Name Thing”, said to have been one year old(?). Levi was a farmer and according to the census records of 1850, 1860 and 1870 held property valued from $250 to $500 over that span of years. By 1870 several of his children, including Prince, still lived with him and his wife Roxanna.

However, by 1880 something radical had happened to Levi. Roxanna is not enumerated with him, even though Levi is listed as married and a boarder with the William Charles family of Rome, Kennebec, Maine (same town and location Levi had been enumerated in for the previous three censuses). There must have been a sad story, for Levi’s occupation was listed as “town pauper” . . . poor Thing.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!