Ghost Town Wednesday: Running Water, Texas

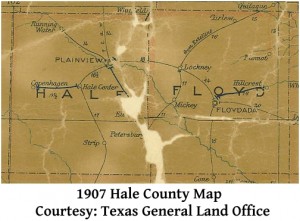

Ranchers were first attracted to this area of Hale County, Texas because of an abundance of water. The J.N. Morrison ranch was established in 1881 and many settlers who came to the area worked there. Ranch operations continued to grow as other cattleman joined the partnership, including Christopher Columbus (C.C.) Slaughter.

Ranchers were first attracted to this area of Hale County, Texas because of an abundance of water. The J.N. Morrison ranch was established in 1881 and many settlers who came to the area worked there. Ranch operations continued to grow as other cattleman joined the partnership, including Christopher Columbus (C.C.) Slaughter.

Slaughter wore many hats during his lifetime — as a Texas Ranger, banker, cattleman and more. As a highly successful businessman, Slaughter made his four million dollar fortune in cattle ranching and land speculation. Born in 1837, Slaughter was a part of history as the Texas Republic took shape. Between 1877 and 1905 he managed to amass more than a million acres of land – from just north of Big Spring and stretching to the New Mexico border — and forty thousand head of cattle . A Dallas newspaper once called him “the Cattle King of Texas”, a title I might add was given to more than one Texas cattle rancher.

Slaughter wore many hats during his lifetime — as a Texas Ranger, banker, cattleman and more. As a highly successful businessman, Slaughter made his four million dollar fortune in cattle ranching and land speculation. Born in 1837, Slaughter was a part of history as the Texas Republic took shape. Between 1877 and 1905 he managed to amass more than a million acres of land – from just north of Big Spring and stretching to the New Mexico border — and forty thousand head of cattle . A Dallas newspaper once called him “the Cattle King of Texas”, a title I might add was given to more than one Texas cattle rancher.

In 1884 Dennis and Martha Rice purchased several sections of land in the area, hoping to establish a town and convince a railroad to lay track.1 They built a dugout south of the community of Edmonson and their settlement was first named Wadsworth. In December of 1890 the first post office was established and on January 28, 1891 the settlement was renamed Running Water to highlight the presence of nearby flowing water.

Rice was appointed the community’s first postmaster and worked as a railroad land speculator. Later in 1891 a school was established and by the following summer, after establishing the Running Water Townsite and Investment Company with $25,000 of initial capital, Rice held a picnic on July 4, ostensibly to sell town lots. On August 26, 1892 the town of Running Water was officially open. The investment company’s directors included Rice, C.C. Slaughter, George C. Pendleton, George Slaughter (all Texans) and R.A. Knight of South Dakota.2

While the prospect of abundant sources of water may have drawn settlers to the area, in the mid-1890’s drought and grasshoppers slowed migration. Then, the Texas legislature passed the so-called Four-Section Act in April of 1895, allowing the sale or lease of up to “four sections of school, asylum or public lands in all Texas counties except El Paso, Pecos and Presidio.”3

With passage of the Four-Section Act settlers again made their way to the area, many of them farmers. The town continued to grow as general stores, a blacksmith shop, grist mill, and Presbyterian, Methodist and Baptist churches were established. The Running Water school continued to expand and by 1924 was an independent district with a PTA organized in 1925 and four teachers by 1937.

Dennis Rice’s original plan included a railroad in order to sell land and attract more settlers. However, when the Fort Worth and Denver Railway began laying track three miles away in 1928, Running Water, like many other prairie towns across the plains of America, hung on for a few years before beginning its decline. On February 1, 1937 the post office was closed and moved to Edmonson Switch and the townspeople began to leave. The nearby springs dried up in the mid-1940’s and all that remains of Running Water is the town’s cemetery, surrounded by a barbed wire fence, near Edmonson.

Other Sources:

Open Plaques, Plainview, Texas

Texas State Historical Association

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Tombstone Tuesday: Abigail Fritter Grigsby (and the case for proving her actual age)

According to her gravestone, Abigail Fritter Grigsby died on August 5, 1860 at the age of 102 years, 8 months and 11 days. The picture I found at Find-A-Grave appears to be of the original gravestone. That would mean she was born on November 25, 1757 if this calculation tool is correct. The Find-A-Grave entry lists her birth date as November 11, 1764 and the death date as August 5, 1860. Clearly, there is some sort of discrepancy, but this isn’t the only “twist” to Abigail’s story …. read on.

According to her gravestone, Abigail Fritter Grigsby died on August 5, 1860 at the age of 102 years, 8 months and 11 days. The picture I found at Find-A-Grave appears to be of the original gravestone. That would mean she was born on November 25, 1757 if this calculation tool is correct. The Find-A-Grave entry lists her birth date as November 11, 1764 and the death date as August 5, 1860. Clearly, there is some sort of discrepancy, but this isn’t the only “twist” to Abigail’s story …. read on.

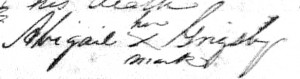

Under oath and by her mark (“X”), Abigail Grigsby swore to the following facts on August 10, 1840 before the Marion County (Indiana) Probate Court:

Abigail Grigsby a resident of the County of Marion State of Indiana aged seventy nine years on the twenty fourth day of November next, who first being duly sworn, according to law, doth on her oath, make the following declaration, in order to obtain the benefits of the provisions made by the act of Congress, passed July 7, 1838, entitled an act granting half pay and pensions to certain widows, that she is the widow of Moses Grigsby, who was a pensioner of the United States of the North Carolina agency, and probably may have been transfered [sic] to the Indiana agency before his death, and she refers to his papers on file for evidence of his services. She further declares that she was married to the said Moses Grigsby in the County of Stafford State of Virginia about two weeks before Christmas day in the year Seventeen hundred and Eighty four, being about the Eleventh day of December, and that she was then twenty three years of age that her husband the aforesaid Moses Grigsby died on the Sixteenth day of June Eighteen hundred and Thirty Eight in Gibson County Indiana; that she was not married to him prior to his leaving the Service but the marriage took place previous the first of January Seventeen hundred and ninety four [illegible] at the time above stated.

She has no family record nor does she believe that the ages of her children were recorded by her husband. She is old and infirm and does not now that she could get a record from Stafford County in Virginia should there be any, and prays that the best evidence she can produce may be received her oldest daughter who is now dead was born in September Seventeen hundred and Eighty five and she was married to the said Moses Grigsby prior to the birth of said child, Nancy Grigsby.

The presiding court officer, R.B. Duncan, was of the opinion: “Abigail Grigsby a resident of Marion County State of Indiana, an aged lady and is well known to the Court to be a lady of truth and made oath to the truth.” Nancy Bingman also swore under oath that Abigail was a “lady of truth”. Mrs. Bingman was aware that Moses had been a pensioner in North Carolina and that he had died on the date which Abigail stated in her declaration.

Her declaration tells me that under oath Abigail swore that she was not born on November 25, 1757 as her gravestone seems to indicate, but rather on November 11, 1761. Further proof can be obtained from her 1840 declaration when Abigail stated she was married in December of 1784 and was twenty-three years of age. The 1761 birth date fits perfectly because she would have just turned twenty-three one month prior to her marriage to Moses Grigsby.

Her declaration tells me that under oath Abigail swore that she was not born on November 25, 1757 as her gravestone seems to indicate, but rather on November 11, 1761. Further proof can be obtained from her 1840 declaration when Abigail stated she was married in December of 1784 and was twenty-three years of age. The 1761 birth date fits perfectly because she would have just turned twenty-three one month prior to her marriage to Moses Grigsby.

However, the 1784 marriage date may have been incorrect because later in August of 1840 the County Clerk of Stafford County, Virginia certified that as best he could read (“in fair legible figures”) the original marriage record the marriage year was in fact 1785. In 1917 Mrs. C.H. Stewart of Delta, Colorado wrote to the Bureau of Pensions in Washington, D.C. requesting information regarding the marriage date and Abigail’s maiden name. In 1915 another woman (illegible) of Holden, Missouri also wrote to the bureau requesting the same information.

In response to one of these requests, the Bureau of Pensions forwarded the following information. Moses Grigsby had enlisted in Virginia and served from April of 1781 until May of 1783 under the command of Captain Abram Fitzpatrick and Colonel Samuel Hanes. Moses had first applied for his pension in October of 1820 in Stafford County, Virginia at the age of fifty-seven, implying that Moses was born ca. 1763.

The following remarks were added to the bureau’s response (as best I can translate them): “d. June 16, 1838 in Gibson County Ind. Soldier married December 1785 in Stafford Co., Va. Abigail or Abby, daughter of Moses Fritter. She was b. November 11, 1761 and was allowed pension on an app. of Aug. 10, 1840 while a res. of Marion Co. Ind.”

By an act of Congress passed on July 7, 1838 (5 Stat. 303), Abigail would have been entitled to a five-year widow’s pension since her marriage had clearly occurred before January 1, 1794. These pensions were subsequently extended by acts passed on March 3, 1843 (5 Stat. 647); June 17, 1844 (5 Stat. 680); and February 2, 1848 (9 Stat. 210). Thus, in 1840 Abigail’s widow’s pension application was well within the bounds of the law passed in 1838.

In July of 1848 Congress passed yet another act which provided not just an extension of benefits but life pensions for widows of soldiers who were married before January 2, 1800. It should be noted that Congress subsequently modified the lifetime widow’s pension requirement by lifting the marriage date restrictions. On March 9, 1878 widows of Revolutionary War soldiers who had served for less than a month or had participated in perhaps just one engagement were eligible for lifetime widow’s pensions.4

Moses’ original pension had been $96 per annum, according to the 1848 declaration of William Mendenhall, an acting Justice of the Peace in Marion County, Indiana. Abigail’s original pension was set at $56.66 per annum and in 1848 Abigail believed she was entitled to Moses’ original pension of $96 per annum. It appears she had been appealing to the courts to grant her Moses’ full pension for quite some time. In 1843 an Indianapolis attorney(?) believed she was entitled to “considerable arrears”. In October of 1850 William Mendenhall again appealed on her behalf for an increase and a settlement in regards to any pension pay which may have been in arrears as of that date.

Obviously, Abigail was in great need of income. In more than one declaration she was described as an “old indigent lady”. It appears that her tenacity paid off eventually since on June 4, 1855 her application for a land bounty (this was one determined woman!) indicates she had indeed been receiving Moses’ full pension of $96 per annum, although the date of the adjustment was not mentioned. By that time Abigail was well over ninety years old and obviously of feeble mind since all requested dates were filled in as “forgotten”, and as far as records “she has none in her possession.”

The land bounty application was filed in Dallas County, Iowa and included an affidavit from John Bingman and Elizabeth (illegible name) who had known Abigail for thirty years (remember, Nancy Bingman had made a similar declaration in 1840). Census records (United States 1850 and 1860 in Marion County, Indiana and the 1856 Iowa State) indicate that Abigail lived with John and his wife Nancy and it’s conceivable she had lived with them for several years. That she and the Bingman family were long-time acquaintances is evident by John and Nancy’s Stokes County, North Carolina marriage record.

In fact, Nancy may have been related to Abigail because her maiden name is listed as “Fletter” (Abigail’s maiden name was Fritter). Makes me wonder if Nancy was a Fritter instead of a Fletter (things that make me go “hmm”). I was wondering where in North Carolina Moses and Abigail had lived, so perhaps it was Stokes County.

There are still several questions about the life of Abigail Fritter Grigsby, yet quite a few historical facts emerged from the sixty-four pages of pension records I found at Fold3. I eventually located some census records which helped shed some light on her relationship with the Bingmans. In 1850 Abigail was enumerated at age 91 with a birth year of about 1759. On July 9, 1860 her age was listed as 102 and her personal estate was $15.

Less than a month later Abigail Fritter Grigsby died. Presumably, John and Nancy Bingman took it upon themselves to pay for her burial and gravestone. Abigail’s recently recorded age of 102 likely accounted for the inscription on her gravestone:

Wife of M Grigsby, aged 102 years 8 months 11 days

Under oath Abigail had repeatedly sworn her date of birth was November 11, 1761, which would mean she hadn’t yet reached the age of 99 at the time of her death, but rather was 98 years, 8 months and 25 days old.

Although I didn’t have enough time to thoroughly examine every pension record (64 pages), I’ve tried to summarize and hopefully present a credible case for Abigail Fritter Grigsby’s actual age at the time of her death in 1860. I often find that family researchers come across these Tombstone Tuesday articles and are thrilled to know more about their ancestor. My hope is that someday a Grigsby or Fritter family researcher may come across this article and find it helpful.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Time-Capsule Thursday: Those Dang Saucers Appear Everywhere

This week in July 1952 was filled with headlines about the strange phenomenon of so-called “flying saucers” or UFOs (unusual or unidentified flying objects). The term had been around since the summer of 1947 when hundreds of incidences of unexplained objects in the sky were reported, many observed by commercial and Air Force pilots.

The Air Force began an investigation, but by late 1947 had found nothing that could have caused these sightings. However, sightings continued despite government reports. Some of these sightings occurred around nuclear power or atomic energy facilities. Sightings continued and the Air Force re-opened the investigation in the fall of 1951. By March of 1952 the project was officially named “Blue Book”.

The Air Force began an investigation, but by late 1947 had found nothing that could have caused these sightings. However, sightings continued despite government reports. Some of these sightings occurred around nuclear power or atomic energy facilities. Sightings continued and the Air Force re-opened the investigation in the fall of 1951. By March of 1952 the project was officially named “Blue Book”.

This article is no longer available for free at this site. It was re-written and enhanced, complete with footnotes and sources and has been published in the October 2018 issue of Digging History Magazine. Other articles in this issue include “American Poltergeist (and other strange goings on)”, “Sister Amy and Her Murder Factory”, Genealogically Speaking: It’s Time to Rake the Leaves”, and more. Should you prefer to purchase the article only, contact me for more information.

This article is no longer available for free at this site. It was re-written and enhanced, complete with footnotes and sources and has been published in the October 2018 issue of Digging History Magazine. Other articles in this issue include “American Poltergeist (and other strange goings on)”, “Sister Amy and Her Murder Factory”, Genealogically Speaking: It’s Time to Rake the Leaves”, and more. Should you prefer to purchase the article only, contact me for more information.

I invite you to check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

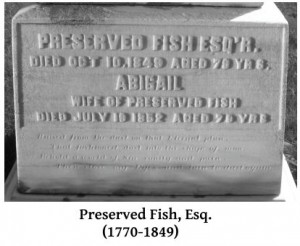

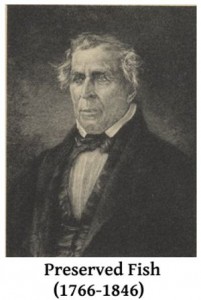

Tombstone Tuesday: Preserved Fish

This name was so unusual I decided to research it a bit. As it turns out, there was more than one person with this name, apparently from the same family line. First of all, the name was most likely not pronounced as we commonly do today (prɘ ˈzɘrvd), but rather something like “pre-SER-ved” or “pres-ER-ved”. Here are a few short biographies of those bearing the name (pay attention — it’s a bit of a tongue-twister at times!).

This name was so unusual I decided to research it a bit. As it turns out, there was more than one person with this name, apparently from the same family line. First of all, the name was most likely not pronounced as we commonly do today (prɘ ˈzɘrvd), but rather something like “pre-SER-ved” or “pres-ER-ved”. Here are a few short biographies of those bearing the name (pay attention — it’s a bit of a tongue-twister at times!).

Preserved Fish (1679-1745)

According to the Fish genealogical record, the first known person with the name “Preserved” was born on August 12, 1679 in Portsmouth, Rhode Island, the son of Thomas and Grizzel (Shaw) Fish. He married Ruth Cook on May 30, 1699 and to their marriage were born these children: Grizzel, Ruth, Thomas, Amy, Sarah, John, Preserved and Benjamin.

His namesake born on May 19, 1713 lived to be ninety-nine years old, dying in February of 1813 as the result of falling on a hatchet. While many of the Fish family were thought to have been of the Baptist faith (Rhode Island was essentially a Baptist colony found by Roger Williams), it appears that Preserved may have been a Quaker since his death on July 15, 1745 was recorded by the Society of Friends.

Preserved Fish (1766-1846)

According to Rhode Island records, this Preserved Fish was born on July 14, 1766 to parents Isaac and Ruth Fish. The Fish genealogical record states, however, that Preserved was born in Freetown, Massachusetts (Isaac was born in Portsmouth, Rhode Island in 1744).

Some sources indicate that his father’s name was also Preserved, while the Fish family genealogical record indicates Isaac was his name. Nevertheless, it appears the name was an old Quaker name that meant “preserved in a state of grace” or “preserved from sin”, according to Jay William Frost, a Quaker historian at Swarthmore College. The Fish family was quite prominent in seventeenth and eighteenth century New England.5

Some sources indicate that his father’s name was also Preserved, while the Fish family genealogical record indicates Isaac was his name. Nevertheless, it appears the name was an old Quaker name that meant “preserved in a state of grace” or “preserved from sin”, according to Jay William Frost, a Quaker historian at Swarthmore College. The Fish family was quite prominent in seventeenth and eighteenth century New England.5

While the name may have been a distinct family name, some had through the years believed it may have been attributed to the story about how he was “picked up from a floating wreck by a New Bedford fisherman, and therefore named Preserved Fish.6 That, of course, is preposterous owing to the fact there was already at least one ancestor pre-dating him who bore the same name.

Isaac was a blacksmith and his son worked in the shop, perhaps hoping that Preserved would follow in his footsteps. That seems not to have been Preserved’s calling, however. He worked for a time as a farmer, but finally the sea called him. He boarded a whaling ship headed for the Pacific and became a captain at the age of twenty-one. The sea may have been in his blood, but Preserved realized that the life of a sea captain wasn’t likely to make him wealthy.

Rather, he realized that his fortune would be made in selling whale oil, not in hunting for it on dangerous sea missions. In 1810 Preserved went into the whale oil business with his cousin Cornelius Grinnell and later with another cousin, Joseph Grinnell. Joseph and Preserved founded the shipping firm of Fish and Grinnell in 1815. Within a few years, owing to Preserved’s keen business acumen, the company became one of New York’s most influential firms.

In 1826 Preserved joined the New York Stock Exchange Board as one of the founders and later became president of the Tradesman’s Bank of New York, a position he held until his death in 1846. Although he was married three times, Preserved never had any biological children, but adopted a son, William Middleton.

Preserved was a Quaker until late in his life when he joined the Episcopal Church. He was a Jacksonian Democrat until joining the Whigs in 1837 in opposition to Martin Van Buren.7 New York newspapers made mockery of the switch – a Whig in New York, home of the infamous Democrat political machine known as Tammany Hall, was openly disdained.

Just as the Mexican-American War was beginning, Preserved Fish died in Portsmouth, Rhode Island on July 22, 1846. His body was returned to New York where he was buried in Vault No. 75 of the New York City Mausoleum, joining the likes of other prominent New York families (many of them bankers).

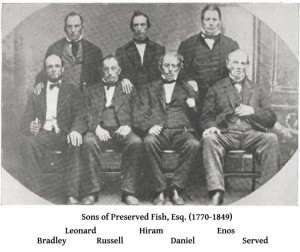

Preserved Fish (1770-1849)

He was the son of Robert and Abigail (Hathaway) Fish, born on November 5, 1770 at the estate of his grandfather Daniel Fish. Abigail died in 1775 and his early years were spent at the home of his older brother Matthew in New Ashford, Massachusetts. He served as Matthew’s apprentice, learning the stone mason trade. At the age of nineteen he purchased his time from Matthew for the sum of sixty dollars, but being poor he found himself indebted for that amount.8

When the New Hampshire Grants were made available (later becoming the state of Vermont) Preserved joined other settlers heading north. His training as a stone mason served him well and he was able to pay the debt owed to Matthew. After clearing his debts, Preserved saved his money and later invested in farm land and property.

In August of 1791 Preserved married Abigail Carpenter and to their union were born ten sons and one daughter. On December 11, 1808 they joined the Ira (Vermont) Baptist Church and later transferred membership to the Middletown Baptist Church in 1819. Preserved was also a Mason and a Knight Templar and family historians note that despite the affiliation he wasn’t precluded from membership at Middletown despite the Anti-Masonic movement (1820-1840).

Preserved became one of the wealthiest members of his community and through the years served in various civic offices. He was a “very large man, tall and powerful” and his ten sons all averaged at least six feet in height. Like Preserved Fish the New York banker, he was also a banker and a successful businessman.

Preserved died on October 10, 1849 of septicemia following an infection of his thumb. His total estate, minus large sums of money loaned to over forty individuals, included railroad and banking investments and totaled just over $45,000. A faithful servant of the people known as Esq. (“Square”) Fish, his tombstone read:

Raised from the dust on that eternal plan

That fashioned dust into the shape of man

Behold a world of sin, vanity, and pain,

Then close my eyes and turn to dust again.9

Preserved Offensend Fish (1882-1935)

This particular Preserved Fish was descended from the son of Vermont Preserved Fish’s son who went by the “abbreviated” name of “Served” and was born on August 14, 1882 in Washington County, New York. The middle name of Offensend came from the second wife of Served, Sally Ann Offensend. Preserved Offensend Fish is the grandson of Served Fish and Sally Ann Offensend Fish and the son of Preserved Offensend Fish (Sr.) who was born in 1851.

Preserved Offensend Fish, Sr. died in 1904 and following his death, Preserved Offensend, Jr. headed west to seek his fortune. In Wyoming he had a profitable cattle business, but lost quite a bit of his fortune following World War I. He married Jennie A. Robinson on September 26, 1911 in Thermopolis. To their marriage were born four children: Sadie, Albert Edward (died at 16 days old), George and Robert.

Preserved roamed Wyoming it seems, living at various times in Thermopolis, Worland, Casper, Buffalo and Ten Sleep. He also lived for a time in Bridger and Belfrey, Montana. He died on October 5, 1935 and is buried in Ten Sleep.

Whether Preserved Offensend Fish was the last to bear the unique family name is unclear to me, although it seems to have been the last one referenced in the family genealogical record – he came from a long line of not just Fishes but “Preserved Fishes”.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

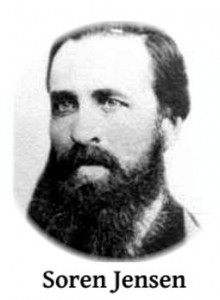

Tombstone Tuesday: Nephi United States Centennial Jensen

A couple of weeks ago my Tombstone Tuesday article asked the question “What’s In a Name?”. I highlighted a few and have since discovered more for future articles. One of the most unique names I came across was a man by the name of Nephi United States Centennial Jensen. Here is his story.

A couple of weeks ago my Tombstone Tuesday article asked the question “What’s In a Name?”. I highlighted a few and have since discovered more for future articles. One of the most unique names I came across was a man by the name of Nephi United States Centennial Jensen. Here is his story.

Nephi United States Centennial Jensen was born on February 16, 1876 to parents Soren and Kjerstine (or Christina) (Rasmussen) Jensen. His Danish heritage is interesting. Soren was born on June 14, 1838 in the town of Hvirring, Denmark. His parents, Jens Peter Sorensen and Anna Kuerstine Jensen were wealthy farmers.

Soren prepared to become a Lutheran minister but in 1859 was introduced to the Mormon faith. After his conversion, Soren worked as a missionary before immigrating to America in 1860. Whether or not his parents approved, family historians10 write that Soren signed away all inheritance rights to his family’s estate and borrowed $173 to pay for passage to New York. Smallpox had broken out on board the ship and for two weeks following arrival no one was allowed to leave the ship.

Soren prepared to become a Lutheran minister but in 1859 was introduced to the Mormon faith. After his conversion, Soren worked as a missionary before immigrating to America in 1860. Whether or not his parents approved, family historians10 write that Soren signed away all inheritance rights to his family’s estate and borrowed $173 to pay for passage to New York. Smallpox had broken out on board the ship and for two weeks following arrival no one was allowed to leave the ship.

Once the quarantine was lifted, Soren joined his fellow Scandinavians and boarded a train to Omaha. At that time, the railroad terminated in Omaha. In order to reach Utah Territory, he joined a caravan of other LDS members who would use wagons and handcarts to cross the vast plains. Before departing, Soren married Elna Peterson, a Swedish convert on July 5, 1860.

That same day the caravan departed with six wagons and twenty-two handcarts. Seventy of the one hundred and twenty-six persons departing that day were Scandinavian who spoke no English. Their journey was full of challenges and dangers, but all arrived safely at the Eighth Ward Square in Salt Lake City on September 24, 1860. Soren and Elna settled in the First Ward and together had four children. He was ordained a Seventy on February 7, 1861.

During the journey across the plains, Soren had proven himself a skillful buffalo hunter. After arriving in Salt Lake City, he became a skillful carpenter and worked on the Mormon Tabernacle for three years. He practiced polygamy – marrying Kjerstine Rasmussen on March 9, 1867 (seven children), Karen Juliusen on April 18, 1868 (six children), Ann Johanna Jensen on September 12, 1878 (three children) and Petrea Cathrina Hansen on February 21, 1884 (five children).

America was celebrating its centennial in 1876 and apparently his parents decided to name their son in its honor. Sometimes he is referred to as Nephi U.S.C. Jensen (for short, I suppose). There were actually several other people named Nephi Jensen, however, and at least one of them appeared several times as a troublemaker of sorts throughout the years in the Salt Lake Tribune.

According to family historians, Soren went on a mission in Denmark from 1876 to 1878 before returning to work as a carpenter in Salt Lake City. In 1885 he was called to St. John, Arizona and the following year to Mancos, Colorado. Presumably, at least some of the family traveled with him, since Nephi attended Union High School in Montezuma County, Colorado from 1892-1893.11

According to family historians, Soren went on a mission in Denmark from 1876 to 1878 before returning to work as a carpenter in Salt Lake City. In 1885 he was called to St. John, Arizona and the following year to Mancos, Colorado. Presumably, at least some of the family traveled with him, since Nephi attended Union High School in Montezuma County, Colorado from 1892-1893.11

One of the children (Katherine) related years later that she and her half-brothers Joseph and Nephi had departed Salt Lake City for Mancos in 1887. Petrea and her children were already residing in Colorado while Soren had traveled back and forth from Arizona to Utah. Katherine and Nephi walked most of the way.

Soren and his family were grain farmers and Joseph and Nephi hauled manure all winter long to fertilize the land. It paid off after two or three years when the land began producing sixty-five bushels per acre. According to Katherine, Nephi was the only child allowed to attend school because her father thought the cowboys made too much trouble and ran teachers out of town. Soren had been a teacher in Denmark and taught his children to read and write.12

However, Nephi was allowed to attend high school and “outstripped all the students in school.”13 The teacher told Soren he couldn’t teach Nephi anymore. Nephi later attended the Latter Day Saints University (1895-6) and the University of Utah, aspiring to become a railroad engineer14. Instead, he received a call to missionary service in the South. The day following his twenty-second birthday Nephi departed Utah.

After arriving in Chattanooga, Tennessee he was assigned to the Florida Conference where he worked until July of 1900. He later traveled back to Arizona to work as a school teacher. There he met Margaret Fife Smith and married her on April 9, 1902.

LDS history doesn’t appear to record that he practiced polygamy, but in 1940 the census records that twenty-six year old Lila L. Jensen was the head of household’s wife. I didn’t find a marriage record, however, and I wonder if perhaps she was their daughter since she was only two years younger than Paul. Margaret is also enumerated as was twenty-eight year old Paul, presumably Nephi and Margaret’s son.

On February 12, 1906, Nephi was admitted to the Utah State Bar and for a few years was engaged in the practice of general law. From January 1, 1911 until August 1, 1913 he served as Salt Lake County’s Assistant County Attorney. He also made a name for himself by serving as a member of Utah’s state legislature during its seventh session (1907-1909).

As a member of the House of Representatives, he and Brigham Clegg were scheduled to give a talk, “by orders of the Federal bunch”. The Salt Lake Tribune referred to him as “the member with the long name”. The newspaper noted that both men were regrettably members from Salt Lake County whose mission was “to work their jaw continuously.”15

Clegg and Jensen were known for their habit of speaking about both sides of an issue and then voting the exact opposite of the way they talked. Clegg was the worst, and although Nephi Jensen was not as talkative as his colleague, he nevertheless was “badly afflicted with mouth disease, and loses no opportunity to get before the House.” Both appeared to be “nit-pickers”, as noted by the Tribune:

Nine-tenths of the motions made to correct the typographical and grammatical errors in the journal are made by these two persons and both labor under the delusion that they are legislating for the State. Several members said to The Tribune Saturday evening that if these two men from Salt Lake county could have their mouths laced as tight as their shoes that some real legislation, some needed legislation, might be enacted.16

Apparently, the actions of Nephi U.S.C. Jensen, who had “received the highest vote of any candidate on the ticket” rankled the Tribune’s editors. After his stint as the assistant county attorney, Nephi formed a law partnership with C.E. Marks (Marks & Jensen). For six years, he and Marks were regarded as one of the most prominent Salt Lake City law firms.

On April 22, 1919 Nephi was called to serve as president of the Canadian Mission with headquarters in Toronto. After his missionary service he returned to Utah and in 1928 was appointed as a Salt Lake County judge. Nephi retired in 1933 and devoted the rest of his life to writing tracts, pamphlets and books, including LDS study manuals.

On September 2, 1955 Nephi United States Centennial Jensen died at the age of seventy-nine in Salt Lake City’s L.D.S. Hospital after experiencing a ruptured appendix. Margaret lived several more years and died in 1969. Both are buried in the Wasatch Lawn Memorial Park cemetery in Salt Lake City.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Far-Out Friday: Robert Wadlow, Gentle Giant

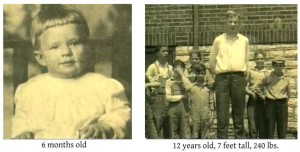

On February 22, 1918, with war raging across the seas in Europe, Harold and Addie Wadlow of Alton, Illinois welcomed their firstborn child into the world – Robert Pershing Wadlow. He was a little over eighteen inches long and weighed eight pounds and six ounces – a perfectly normal size and weight for a baby. Little did his parents know, however, what the future held for their firstborn child as six months later his height had almost doubled, his weight nearly quadrupled.

On February 22, 1918, with war raging across the seas in Europe, Harold and Addie Wadlow of Alton, Illinois welcomed their firstborn child into the world – Robert Pershing Wadlow. He was a little over eighteen inches long and weighed eight pounds and six ounces – a perfectly normal size and weight for a baby. Little did his parents know, however, what the future held for their firstborn child as six months later his height had almost doubled, his weight nearly quadrupled.

His height and weight steadily increased – by the third grade Robert, towering over all his classmates, was taller than his teacher. Despite his size, however, he spent what would be considered a normal childhood – playing with friends, running a lemonade stand and joining the Boy Scouts. The Bloomer Shoe Factory made a special pair of size seventeen shoes for eight year-old Robert.

When exactly the rest of the world outside his family and friends in Alton began to learn about the boy who would later be called Alton’s “Gentle Giant” is unclear. One woman interviewed for a documentary about his life said she had never heard of him until one day she was outside and noticed a “man” riding along in a red wagon. Robert’s family had just moved across the street.

When exactly the rest of the world outside his family and friends in Alton began to learn about the boy who would later be called Alton’s “Gentle Giant” is unclear. One woman interviewed for a documentary about his life said she had never heard of him until one day she was outside and noticed a “man” riding along in a red wagon. Robert’s family had just moved across the street.

Around Alton and neighboring areas, attention was drawn to him perhaps as early as 1927 when one newspaper called him “A Man at Eight” – he was taller than his father by then:

At the age of ten he was wearing size fifteen shoes. Five square feet of leather – a lot of cow, as one newspaper reported – was required to make them.

By the age of twelve, Robert was about seven feet tall and weighed two hundred and forty pounds. Like other boys his age, he loved to play baseball, football and basketball and hoped to someday fly like his idol, Charles “Lindy” Lindbergh – if he could find a plane big enough – or maybe he would become a movie star.

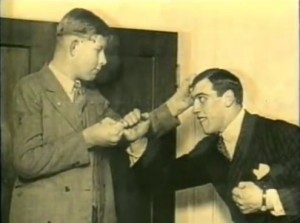

Around that time, an Italian named Primo Canera was making headlines for his athletic prowess as a boxer. At six feet and five inches Canera towered over his opponents and much of the press surrounding him emphasized his “gigantic” frame. His promoters thought it would improve gate receipts when he fought in St. Louis if Robert met him for publicity photographs. Canera, assuming he was meeting with a small child, agreed – what would be the harm? Plenty, according to a documentary about Robert’s life. Canera was proud of his height and weight, but posing with a “mere child” who stood even taller, turned out to be somewhat of an embarrassment.

That same year Robert’s parents finally took him to Barnes Hospital in St. Louis to find out what was causing his unusual growth. There they were told their son’s condition was due to an overactive pituitary gland. Although surgical options were available, the risks were high, possibly resulting in death. Robert suffered no mental disabilities (his IQ was quite high), and although significantly larger than other children was still proportionately adjusted in weight and height. For his parents, surgery was out of the question.

Even so, it must have been difficult for a boy his age to blend in and not draw attention to himself. As one can imagine he was teased, yet according to one of his classmates he took it in stride. Although he would blush with embarrassment, he would never become angry. Robert continued on to high school and wanted to participate in basketball, although coaches were fearful he would hurt himself. By the time team officials were able to have a custom pair of shoes made for him the season was over.

Although he had to drop out of school for approximately six months due to a foot infection, Robert made up the required course work and graduated in January of 1936. His cap and gown required fourteen square yards of material. At eight feet, three and-a-half inches, he was the tallest high school graduate in history.

He enrolled at Shurtleff College with a goal of studying law but after only one semester decided to pursue a career in business. The International Shoe Company, as the makers of his specially-sized shoes, had known about Robert for some time. He worked for them as a field representative and the company displayed a copy of Robert’s gigantic shoes in their stores.

Robert traveled with his father to these stores where Harold would give a short talk about his son, and then they would depart so that the store could make their sales pitch to those who had gathered to see Robert up close and personal. Although a fairly well adjusted and mild-mannered person, Robert would get angry when people came up and asked him what he ate.

One sales representative who traveled with the Wadlows related how Robert would also become angry when someone came behind him and pinched the back of his legs to see if he was walking on stilts. The sales rep also related how he and Harold had to “nudge” Robert along as they were walking down the hallway on the way to their hotel room. With his extreme height, Robert was able to look through the door transoms as they walked by. They had to make sure Robert didn’t linger too long or disturb other hotel guests.

Robert’s clothing and shoes, of course, had to be custom-made. In 1936 a pair of size 39 shoes costing $88 to make was returned to the shoe company – they pinched his feet. Harold and Addie made plans to build a special house for their oversize son in 1937, but to their dismay discovered that such things as a ten-foot long bathtub didn’t exist, unless one was specially cast for him at a cost of $500 to $1,000.

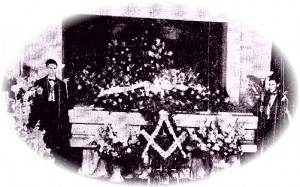

A stint with the Ringling Brothers Circus and other promotional tours brought him increasing notoriety throughout the country. Still, his family always wanted to ensure he lived a normal life. When Robert traveled he was always anxious to return home to be with his family. In 1939 he petitioned the Franklin Masonic Temple of Alton for membership as a Freemason. By year’s end he had been elevated to the degree of Master Mason. At a gargantuan size 25, his ring was the largest one ever created for a member of that lodge. The lodge also built a special chair where he could sit comfortably and participate in regular meetings and activities.

Eventually, walking would become a laborious task, difficult enough to require braces. Yet, he remained an affable and well-adjusted person who loved meeting people, especially children. He continued to grow and on June 27, 1940 he once again visited Barnes Hospital for a checkup. That day his recorded height was an astounding 8 feet, 11.1 inches with a weight of 439 pounds. With that measurement, Robert Wadlow officially became the tallest person in history.

He was scheduled to begin another promotional tour two days later and on July 4 complained of a brace which was irritating his ankle. A blister had formed which resulted in an infection. Robert was taken to a hospital where emergency surgery and a blood transfusion were performed. His temperature continued to soar, and ten days later on July 15, 1940 Robert Wadlow passed away at the age of twenty-two.

His body was returned to Alton where he lay in state in a specially-designed ten foot long casket as thousands of people came for the viewing. Eighteen men, including twelve of his fellow Masons, were required to carry his 855-pound casket. One thousand people congregated near the funeral home and thousands more heard the services through loud speakers. Flags were flown at half-mast on public buildings as Alton mourned its most famous resident.

Robert was buried in a double-sized, twelve-foot, cemetery plot in Oakwood Cemetery. To the world he may have been a curiosity, but to the residents of Alton he was remembered as a friend to many, a kind and gracious person throughout his life. His parents could have chosen surgery to “fix” Robert, but had instead decided to let time and nature take its course and let Robert be Robert, the “Gentle Giant”.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? That’s easy if you have a minute or two. Here are the options (choose one):

- Scroll up to the upper right-hand corner of this page, provide your email to subscribe to the blog and a free issue will soon be on its way to your inbox.

- A free article index of issues is available in the magazine store, providing a brief synopsis of every article published in 2018. Note: You will have to create an account to obtain the free index (don’t worry — it’s easy!).

- Contact me directly and request either a free issue and/or the free article index. Happy to provide!

Thanks for stopping by!

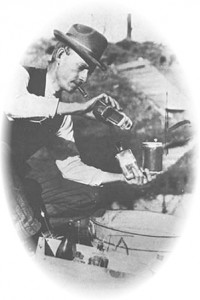

Wild Weather Wednesday: Rainmaking (Part Four) – The Moisture Accelerator

Frank Melbourne mysteriously disappeared, although he had long since been found to be a fraud. (In case you missed previous articles, check out Part One, Part Two and Part Three of this series.) Yet, that didn’t stop other so-called rainmakers from attempting to make a buck. The early twentieth century’s most famous rainmaker was called the “Moisture Accelerator”.

Frank Melbourne mysteriously disappeared, although he had long since been found to be a fraud. (In case you missed previous articles, check out Part One, Part Two and Part Three of this series.) Yet, that didn’t stop other so-called rainmakers from attempting to make a buck. The early twentieth century’s most famous rainmaker was called the “Moisture Accelerator”.

Charles Mallory Hatfield, aka the “Moisture Accelerator”, was born on July 15, 1875 in Fort Scott, Kansas and sometime in the 1880’s his family moved to southern California. In 1894 they moved to San Diego County where his father bought a ranch. As a young boy, Charles sold newspapers on the streets of the city.

Charles Mallory Hatfield, aka the “Moisture Accelerator”, was born on July 15, 1875 in Fort Scott, Kansas and sometime in the 1880’s his family moved to southern California. In 1894 they moved to San Diego County where his father bought a ranch. As a young boy, Charles sold newspapers on the streets of the city.

Although Hatfield was later employed as a sewing machine salesman, he also studied “pluviculture” – rainmaking – in an attempt to create his own secret formula. By 1902 he had a formula of twenty-three chemicals which actually produced a bit of drizzle at his father’s farm located in the San Diego area.

This article is no longer available for free at this site. It was re-written and enhanced, complete with footnotes and sources and has been published in the September 2018 issue of Digging History Magazine. Should you prefer to purchase the article only, contact me for more information.

This article is no longer available for free at this site. It was re-written and enhanced, complete with footnotes and sources and has been published in the September 2018 issue of Digging History Magazine. Should you prefer to purchase the article only, contact me for more information.

I invite you to check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Time Capsule Thursday: July 4, 1876 (It Was A Blast!)

July 4, 1876 – The United States was celebrating its first centennial eleven years following the end of the Civil War. In Philadelphia, soldiers from the North and South, “the Blue and the Gray”, marched together. There were lively and soul-stirring festivities held throughout the country, speeches galore, fireworks – or “Gunpowder and Glory” as The Times of Philadelphia reported.

As cannons were fired and firecrackers lit, explosions and costly fires marred the festivities for some. In Philadelphia one headline read “A Salute That Cost One Hundred Thousand Dollars”. Around one o’clock on the afternoon of the Fourth, some boys fired off a cannon salute which ignited a pile of chips behind a flour mill. Within fifteen minutes the entire block was engulfed in flames.

As cannons were fired and firecrackers lit, explosions and costly fires marred the festivities for some. In Philadelphia one headline read “A Salute That Cost One Hundred Thousand Dollars”. Around one o’clock on the afternoon of the Fourth, some boys fired off a cannon salute which ignited a pile of chips behind a flour mill. Within fifteen minutes the entire block was engulfed in flames.

“A Dynamite Horror” occurred around the same time elsewhere in Philadelphia. A druggist, Dr. H.H. Bucher, was apparently experimenting with explosives in an attempt to create his own pyrotechnics.

This article is no longer available for free at this site. It was re-written and enhanced, complete with footnotes and sources and has been published in the July 2018 issue of Digging History Magazine. This issue also includes other like “Declaring Independence: May 20, 1775 or July 4, 1776?”, “Radical Presbyterianism: Seeds of Revolution?”, “Drawing the Line: Quakers in Conscientious Crisis”, and more. Should you prefer to purchase the article only, contact me for more information.

This article is no longer available for free at this site. It was re-written and enhanced, complete with footnotes and sources and has been published in the July 2018 issue of Digging History Magazine. This issue also includes other like “Declaring Independence: May 20, 1775 or July 4, 1776?”, “Radical Presbyterianism: Seeds of Revolution?”, “Drawing the Line: Quakers in Conscientious Crisis”, and more. Should you prefer to purchase the article only, contact me for more information.

I invite you to check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Tombstone Tuesday: Josiah Wilson Rainwater

Josiah Wilson Rainwater was born on October 10, 1843 in Waterloo, Pulaski County, Kentucky to parents Bartholomew and Nancy McLaughlin Rainwater. He was the youngest of eleven surviving children born to their marriage and named after Reverend Josiah Wilson, a minister and Revolutionary War veteran.

Josiah Wilson Rainwater was born on October 10, 1843 in Waterloo, Pulaski County, Kentucky to parents Bartholomew and Nancy McLaughlin Rainwater. He was the youngest of eleven surviving children born to their marriage and named after Reverend Josiah Wilson, a minister and Revolutionary War veteran.

Josiah was seventeen years old when the Civil War began in 1861 and following his eighteenth birthday in October he enlisted at Camp Wolford, south of Somerset, on November 1. Two months later on January 1, 1862 he mustered into the 3rd Kentucky Infantry, Company D at Camp Boyle as a private, joining his older brother Miles who served in both the 1st and 3rd Kentucky Infantry.

On December 31, 1862 while engaged at the Battle of Stone River in Murfreesboro, Tennessee under the command of General William Rosecrans, Josiah sustained a bullet wound to his hand. In November of 1862 he was promoted to Corporal and in March of 1863 advanced to the rank of Sergeant. During the Battle of Kennesaw Mountain on June 27, 1864 he sustained serious wounds to his hip and chest which required two months of hospitalization. After three years of service, Josiah was mustered out on January 10, 1865 in Louisville, Kentucky.

He returned to Pulaski County and married Elizabeth Jane Weddle on January 19, 1866. Their first child, Martha Jane, was born later that year on October 24. Eight more children were born to their marriage: Nancy Frances (1869), Lucy Isadore (1872), Doretta (1874), Miles (1876), Mary (1879), Cornelia (1881), Roscoe (1883) and Minnie (1885).

In 1883 Josiah applied for his Civil War pension and received $1.00 per month as compensation for his service and battle wounds. In 1870 his elderly parents Bartholomew and Nancy were living with his family. In July of 1889 he wrote a letter to Miles who lived in Oregon, informing him of their father’s death following a stroke: “Everything was done for him that could be done, but human power could not save him.”16

The following year Josiah left Kentucky and migrated with his family to Williamson County, Texas. Why he left is unclear, but Rainwater family researchers theorize that returning soldiers experienced a kind of “post-war malaise” following the Civil War, finding Pulaski County no longer a “good Christian place” to raise their families.

Josiah founded the town of Waterloo, named after his childhood home in Kentucky, and served as the town’s postmaster from 1897 until 1901. In 1907 he moved to Oklaunion in Wilbarger County and remained there the rest of his life. Through the years he had been involved in the civic affairs of the communities where he lived. In both 1880 and 1910 he served as a census enumerator, served as a school board and bank trustee, deputy sheriff, tax collector, deacon in his church and achieved the rank of Worshipful Master as a Mason.

Josiah founded the town of Waterloo, named after his childhood home in Kentucky, and served as the town’s postmaster from 1897 until 1901. In 1907 he moved to Oklaunion in Wilbarger County and remained there the rest of his life. Through the years he had been involved in the civic affairs of the communities where he lived. In both 1880 and 1910 he served as a census enumerator, served as a school board and bank trustee, deputy sheriff, tax collector, deacon in his church and achieved the rank of Worshipful Master as a Mason.

It appears that all of his children came to Texas with him and remained there, some in Williamson County and several in Wilbarger County. His son Roscoe, born on July 4, 1883, worked as a bookkeeper and paymaster with the Panama Canal project. Upon his return to the United States he farmed and pursued various business interests in Wilbarger County.

By the time Josiah died on March 16, 1934 at the age of ninety he was believed to have been one of the oldest Master Masons in Texas. His obituary mentioned he was a “captain under General U.S. Grant in the civil war”.17 That information probably came from family members who remembered a certificate which hung in Josiah’s home for years, indicating he had received a commission as a captain in the Army of the Cumberland. However, for the 1890 census of Civil War veterans Josiah was enumerated as a sergeant, reflecting his official Civil War service record.

Elizabeth died at the age of ninety-five on June 25, 1943 of pneumonia, contracted after going out in a rainstorm to tend to her chickens. She is buried alongside Josiah in Vernon’s Eastview Memorial Park.

While performing some follow-up research for another article, I came across the subject of today’s article. What caught my attention was the fact he was born in Pulaski County, Kentucky, home to many of my maternal ancestors and later moved to a Texas county that was home to my paternal great-great grandmother Catherine “Kate” Hall Bolton. She lived in the community of Fargo, about ten miles north of Vernon. Other records I came across indicate there were Rainwaters living in Hamilton County, Texas as well, home to my great-great grandparents, John Wesley and Mary Angeline Brummett.

It’s certainly possible Josiah was related either directly or indirectly by marriage to some of my Kentucky kin. I saw at least one record of a Chaney (part of my maternal ancestral line) marrying a Rainwater. There may actually be something to the “six degrees of separation” theory after all!

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Tombstone Tuesday: Christopher Mann (1774-1885)

I came across this interesting person recently while researching the two-part series on Chedorlaomer “Lomer” Griffin (Part One, Part Two), who for many years was believed to have been born in 1759 when in fact he was born in 1772. At the time of his death he was actually one hundred and six years old. Lomer’s obituary was published in 1878 around the country and several mentioned another centenarian, Christopher Mann of Independence, Missouri, who at the time was well over one hundred years old.

I came across this interesting person recently while researching the two-part series on Chedorlaomer “Lomer” Griffin (Part One, Part Two), who for many years was believed to have been born in 1759 when in fact he was born in 1772. At the time of his death he was actually one hundred and six years old. Lomer’s obituary was published in 1878 around the country and several mentioned another centenarian, Christopher Mann of Independence, Missouri, who at the time was well over one hundred years old.

Christopher Mann was born on September 15, 1774 in Virginia, within a few miles of George Washington’s homestead, to parents Jonas and Agnes (Williams) Mann. Jonas, born in New Jersey and one of thirteen children, was the grandson of German immigrants.

Christopher Mann was born on September 15, 1774 in Virginia, within a few miles of George Washington’s homestead, to parents Jonas and Agnes (Williams) Mann. Jonas, born in New Jersey and one of thirteen children, was the grandson of German immigrants.

This article is no longer available for free at this site. It will be republished in a future issue of Digging History Magazine. I invite you to check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

This article is no longer available for free at this site. It will be republished in a future issue of Digging History Magazine. I invite you to check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!