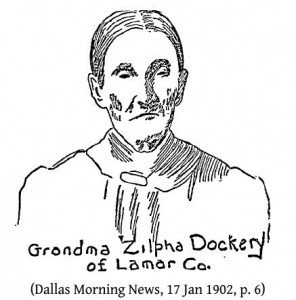

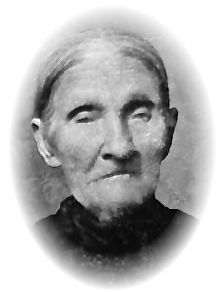

Tombstone Tuesday: Zilpha Etta Scott Dockery (1796-1903)

She was born on September 8, 1796 in Virginia and moved with her family to Spartanburg, South Carolina at the age of three, an event she remembered vividly in 1902 when interviewed by the Dallas Morning News. John Scott was a farmer and the father of three sons and eight daughters.

She was born on September 8, 1796 in Virginia and moved with her family to Spartanburg, South Carolina at the age of three, an event she remembered vividly in 1902 when interviewed by the Dallas Morning News. John Scott was a farmer and the father of three sons and eight daughters.

While most of her family appears to have died young, Zilpha would more than outlive all of them, her life spanning three centuries. When she was born George Washington was serving his second term as the first president of the United States. Although Napoleon Bonaparte had just married Josephine his rise to power had not yet evolved.

“My people were hard-working people,” she declared. “We worked in the fields with plows drawn by oxen and made crops that way for my father the year before I was married.”1 Her childhood dresses were made of flax cloth, although she fondly remembered the first calico dress she made.

“Calico was so skeerce and expensive we couldn’t afford any flounces and frills and trains them days.” Instead, Zilpha wove flax cloth and traded it yard for yard for calico. It was “purty”, she remembered in 1902, and she herself was “naturly purty”. In those days folks didn’t wear their shoes on the way to church, corn shuckings, logrollings, weddings or fairs. They would walk barefoot until reaching their destination, put their shoes on and take them off again before walking home.

Zilpha married William Hiram Dockery in 1818, with whom she had nine children – six sons and three daughters. From Spartanburg, they moved and settled among the Cherokee Indians in Alabama. At that time the Cherokee lived much like the white man, very rich and owning Negro slaves. That would change as more white settlers arrived and gradually forced the Indians to relinquish their land.

William was hired by the government to transport the Cherokees from Alabama to Texas and the Indian Territory. She remembered a great many of them committed suicide rather than leave their beloved land. During the trek William contracted swamp fever and died soon after returning in 1846 or 1847. In 1856 she married John Diffy, a veteran of the War of 1812 and a personal friend of General (and later President) Andrew “Old Hickory” Jackson. John died about a year later and Zilpha changed her name back to Dockery.

William was hired by the government to transport the Cherokees from Alabama to Texas and the Indian Territory. She remembered a great many of them committed suicide rather than leave their beloved land. During the trek William contracted swamp fever and died soon after returning in 1846 or 1847. In 1856 she married John Diffy, a veteran of the War of 1812 and a personal friend of General (and later President) Andrew “Old Hickory” Jackson. John died about a year later and Zilpha changed her name back to Dockery.

Zilpha, or “Grandma Ziff” as she was known to her family, was a great cook and baker who made her pin money selling gingercake and cider. People would come from miles around when she cooked for weddings, fairs, cotton pickings, corn shuckings, logrollings, quiltings – until she was 100 years old, any event where folks congregated en masse. During the Civil War she was also on hand for muster days to cook “a good square meal”. “And, my Columbus, how they did eat!”, she exclaimed.

In the 1890’s she moved with her descendants to Lamar County, Texas. In 1902 the reporter who interviewed Zilpha surmised that her longevity may have been due to a “primitive mode of living”. C.W. Driskell, her son-in-law offered her a comfortable home upon arriving in Texas, yet she preferred living the primitive style she had always known. The reporter shivered while Zilpha paid absolutely no mind as the wind blew through the cracks – and summer was still better suited for bare feet than shoes!

One of the most amazing things occurred after Zilpha reached the century mark. She had never attended a day of school in her life, yet at the age of one hundred years she decided to teach herself the alphabet and learned to read. In 1902 at the age of 105 her memory was still remarkably sharp, although she had begun to slow down a bit and was losing her eyesight and occasionally experiencing “drunk and swimming spells”.

Her taste in clothing remained “old-fashioned” as she continued to knit her own stockings and gloves. Zilpha enjoyed traveling and would spend a great deal of time visiting her family scattered across north Texas. During her life she had never been seriously ill, took salts once in awhile for her stomach, and maybe a nip of brandy now and then (even as a staunch Baptist!). She was still using snuff but had given up smoking just a short time before the interview – the “drunk and swimming spells” to blame. The reporter noted she still hadn’t quite yet kicked the habit – reaching over to borrow C.W.’s cigar, she enjoyed a few satisfying puffs.

Her vivaciousness and zest for life was evident as she answered questions about her past and shared stories from days gone by. When asked if she believed in witches Zilpha told a story about her cows once beginning to give bloody milk that smelled bad. An old neighbor lady shared a remedy to determine if a cow had been witched.

She put the milk in a pot on the fire and whipped the milk out into the fire with a bundle of willow switches while it was boiling. According to the old lady, whoever withced the cows was supposed to walk through the door. Zilpha sent all of her children out of the room and while whipping the milk in walked none other than her sister-in-law Bessie Gilbert. Bessie asked, “Zilph, what in the devil are you doing there?”. Zilpha replied, “Well, the devil has come.” She never would say whether she believed in witches, however.

Oh, and she was opinionated! As a devout Baptist she had walked a half mile or more to preaching for years, although in the early twentieth century she “had no patience with the common run of preachers of these days”. In her day they preached from Bible “without any put on and show to plain, sensible people, many of whom attended in their shirtsleeves, barefooted, in log cabins and under trees.” The preacher himself might be in shirtsleeves – and back in his own field the next day to make a living rather than charge for his preaching. In her opinion, the preachers of 1902 were all for the “almighty dollar”.

The Victorian style of dress was on its way out and Grandma Ziff had “plumb contempt” for that sad state of affairs as well. Her reasoning: the girls of that day were so foolish and uglier than in her day. Thus, it took more fine dressing to make themselves look as purty as she had been in her youth. Grandma Ziff was definitely one-of-a-kind and plenty feisty.

A year after the interview Zilpha Dockery took ill one day, became unconscious and died on January 14, 1903 at the age of 106. She was buried in the Shady Grove Cemetery in Pattonville, Lamar County, Texas. Inexplicably, newspapers outside of Texas reported her as a “colored woman”. If you’d like to read more about Zilpha, see the Find-A-Grave entry here.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Feisty Females: Sarah Jane Ames

If ever a person of the fairer sex could be called a “renaissance woman” it may have been Sarah Jane Ames. When Sarah died in 1926 she was hailed as one of Boone County, Illinois’s “most virile, energetic, and withal most interesting citizens”.

She was born Sarah Jane Hannah in Montreal, Canada on December 4, 1843, and in 1854 migrated to Belvedere, Illinois with her parents (Thomas and Jane) and two brothers. Save for a few years she later spent pioneering in South Dakota, Sarah remained in Boone County the remainder of her life.

She was born Sarah Jane Hannah in Montreal, Canada on December 4, 1843, and in 1854 migrated to Belvedere, Illinois with her parents (Thomas and Jane) and two brothers. Save for a few years she later spent pioneering in South Dakota, Sarah remained in Boone County the remainder of her life.

Did you enjoy this article snippet? This article has been updated with new research and published in the November-December 2019 issue of Digging History Magazine. The magazine is on sale in the Digging History Magazine store and features these stories:

Did you enjoy this article snippet? This article has been updated with new research and published in the November-December 2019 issue of Digging History Magazine. The magazine is on sale in the Digging History Magazine store and features these stories:

- The Burr Conspiracy: Treason or Prologue to War

- Finding War of 1812 Records (and the stories behind them)

- Sarah Connelly, I Feel Your Pain (Adventures in Research: 1812 Pension Records)

- Essential Skills for Genealogical Research: Noticing Notices

- Bullets, Battles and Bands: The Role of Music in War

- Feisty Female Sheriffs: Who Was First?

- The Dash: Bigger Family: (A Bigger and Better Story)

- Book reviews, research tips and more

Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 85-100+ pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

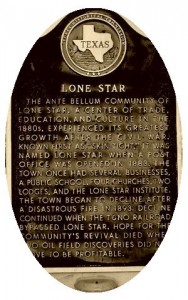

Ghost Town Wednesday: Lone Star, Texas

This ghost town in northeast Cherokee County was first known as “Skin Tight”. According to legend the community got that name after cattle buyer and merchant Henry L. Reeves opened a store. It’s believed the name was due either to Reeves’ “close trading tactics” or perhaps because he worked as a trapper and animal skinner.

This ghost town in northeast Cherokee County was first known as “Skin Tight”. According to legend the community got that name after cattle buyer and merchant Henry L. Reeves opened a store. It’s believed the name was due either to Reeves’ “close trading tactics” or perhaps because he worked as a trapper and animal skinner.

The town had begun to take shape in several years earlier in 1849 when Hundle Wiggins settled there after the Texas Legislature created Cherokee County in 1846. Reeves built a store there in the early 1880’s and on June 13, 1883 a post office was established under the name “Lone Star”. Not long afterwards Reeves moved to Smith County and was shot to death in Troup on June 13, 1886.

By 1885 Lone Star had grown to a population of 160 with a cotton gin, gristmill, sawmill, general store and school. The town was somewhat isolated but the town continued to grow steadily. Both Woodmen of the World and the Masons established chapters in the small community.

By 1885 Lone Star had grown to a population of 160 with a cotton gin, gristmill, sawmill, general store and school. The town was somewhat isolated but the town continued to grow steadily. Both Woodmen of the World and the Masons established chapters in the small community.

By 1890 there were three mercantile stores and a millinery shop in the business district. In 1893 a fire swept through the business section of town and destroyed all but two buildings. The fire started in the offices of Dr. J.E. Rowbarts, who died in the fire. No one was ever able to determine the exact cause although it was common knowledge the doctor kept a cannister of black powder in his office.

The town was rebuilt quickly and resumed its growth, reaching a population of three hundred by the mid 1890’s, aided in part by the Lone Star Institute established by Colonel T.A. Cocke and Reverend M.A. Stewart in 1889. The school’s reputation for excellence led many families to settle in Lone Star and remain after their children had graduated.

Lone Star had four churches – Universalist, Methodist, Baptist and Church of Christ – along with three saloons. One of those was closed following the Blizzard of 1898 when its beer stock stored in the cellar froze and burst.

Lone Star’s decline began at the turn of the century, especially after the Texas and New Orleans Railroad bypassed it in 1903. Instead, the railroad was built through nearby Ponta, where many merchants and residents moved. In 1915 the population was two hundred and the post office closed the following year.

Even after oil was discovered nearby in 1939 the town failed to revive since the field never produced much. The Lone Star Oil Field produced 878,051 barrels and the Lone Star Pettit Field just over 6,000 barrels before both sites were shut down in 1960. A few businesses were still hanging on in 1940 but after World War II even more residents chose to leave.

In April of 1986 Lone Star was designated as a historical site. By the 1990’s only an old weather-beaten blacksmith shop remained. Not a whole lot has been written about Lone Star and except for the historic marker most people wouldn’t even know a town ever existed there. At the dedication ceremony in 1986, John Mark Lester spoke about the “Saga of Lone Star”:

The people who settled Lone Star never were able to build a lasting town for themselves and their descendants, but old Lone Star is not forgotten when the history of Cherokee County is told. There are numerous stories and incidents that have not been told her this afternoon such as the story of Sam Asbury Lindsay, Jr. who came to Lone Star in 1900 and was so impressed with the telephone system that he went on to found what is the $221 million United Telecom Company. The Town’s star rose, glowed brightly for a time, dimmed, died, and never could be rekindled. The crumbling old blacksmith shop, the abandoned old cemetery, a few old homes and business building foundations lost in the weeds are the mute evidence that a town once was on this site. Lone Star lives in our memories and now in our history.2

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Tombstone Tuesday: Carbon Petroleum Dubbs (a “for-real” name with a rags-to-riches story)

Carbon Petroleum Dubbs was born in Franklin, Pennsylvania to parents Jesse and Jennie (Chapin) Dubbs on June 24, 1881. Jesse was born in the same county (Venango) in 1856, around the time the country’s first oil was discovered, and grew up during the early boom years. It wasn’t surprising that Jesse, son of druggist Henry Dubbs, developed a fascination with the oil industry, nor that he named his son after one of oil’s elemental components. Carbon later added a “P.” to his name to make it more “euphonious”. When people began calling him “Petroleum” (perhaps people assumed that’s what the “P” stood for) the name stuck, thus he became known as “Carbon Petroleum Dubbs” (“C.P.”).

Carbon Petroleum Dubbs was born in Franklin, Pennsylvania to parents Jesse and Jennie (Chapin) Dubbs on June 24, 1881. Jesse was born in the same county (Venango) in 1856, around the time the country’s first oil was discovered, and grew up during the early boom years. It wasn’t surprising that Jesse, son of druggist Henry Dubbs, developed a fascination with the oil industry, nor that he named his son after one of oil’s elemental components. Carbon later added a “P.” to his name to make it more “euphonious”. When people began calling him “Petroleum” (perhaps people assumed that’s what the “P” stood for) the name stuck, thus he became known as “Carbon Petroleum Dubbs” (“C.P.”).

Jesse set up a “dinky” chemistry lab in a small oil field and began experimenting in an attempt to discover a way to produce gasoline from crude oil. In 1890 his neighbor, Senator Richard Quay, had him arrested for “maintaining a common nuisance” – the stench was more than the senator could bear. A trial was held a few months later and a split decision resulted – yes, he was guilty of creating a nuisance but on the second charge of continuing a nuisance he was exonerated. However, as the newspaper headline asked – “Will This Stop the Bad Odor?”3

As an “inveterate tinkerer”4 Jesse was constantly discovering new ways to use petroleum. Like his father Henry he was a druggist by trade, inventing a protective jelly for miners, as well as inventing a process to extract sulfur from crude oil. His experiments took him far and wide around the world, despite once being kidnaped by Mexican bandits and held for a $10,000 ransom. After C.P. married Bertha Chatley in 1901 the father and son team began working on a high temperature cracking process, later to be known as the “Dubbs Process”.

As an “inveterate tinkerer”4 Jesse was constantly discovering new ways to use petroleum. Like his father Henry he was a druggist by trade, inventing a protective jelly for miners, as well as inventing a process to extract sulfur from crude oil. His experiments took him far and wide around the world, despite once being kidnaped by Mexican bandits and held for a $10,000 ransom. After C.P. married Bertha Chatley in 1901 the father and son team began working on a high temperature cracking process, later to be known as the “Dubbs Process”.

Jesse tried for years to convince investors his invention would revolutionize the oil industry. In 1909 he traveled to California “flat broke”, only to be ignored by oil company executives. One went so far as to say Jesse himself was a bit “cracked”. Yet, he continued to explore and invent – in 1909 he discovered a way to produce asphalt.

J. Ogden Armour, a hugely successful businessman at the time, invested in several companies besides his own meat packing enterprise, like the Standard Asphalt & Rubber Company. Jesse’s idea for producing asphalt would be valuable enough for his business, yet Armour also believed the oil cracking process could benefit the oil industry. Unfortunately, Jesse died in California in 1918 and C.P., a chemical engineer who graduated from the University of Western Pennsylvania and the Philadelphia College of Pharmacy and Science, took over where his father left off.

Armour purchased Jesse’s patents and made certain the process did indeed work by hiring C.P. to prove it. Armour had founded National Hydrocarbon Company, later known as Universal Oil Products, LLC (UOP), and appointed Hiram Halle to run it. One of Halle’s assignments was to keep C.P. focused on the task at hand – but, like his father, C.P. was a tinkerer. Rather than concentrate on proving his father’s patents, C.P. began experimenting with new processes. He eventually came up with a new process called clean circulation, which would prove to be even more revolutionary than the original Dubbs Process.

World War I brought huge contracts to the Armour company for its canned meats. However, when the war ended the company was left “holding the bag” with a tremendous amount of meat when wartime contracts were abruptly cancelled. For one hundred days, the company bled one million dollars a day.

Armour died broke in London in 1927 after his fortune crumbled. His creditors refused to consider the oil-cracking process stock as payments of his debts, ignoring UOP altogether – considering a handful of patents the company held of little worth, creditors took a pass. Instead, the stock passed to Mrs. Armour.

Meanwhile, C.P. continued to tinker and file patents. In 1929 he was awarded the John Scott medal for “the discovery and development of a process for producing gasoline on a large scale.”5 His (and his father’s) diligence and ingenuity, however, was set to be handsomely rewarded in 1931.

In 1930 the Armour estate closed in probate court, showing insolvency of over 1.8 million dollars – quite a plummet from a record $150,000,000 years before. Early in January 1931 Shell Union and Standard Oil of California purchased UOP and its stock for $22,249,999, making Lolita Sheldon Armour once again wealthy. Since her husband’s death, Mrs. Armour remained convinced the company her husband had originally invested over three million dollars in would somehow redeem itself.

With the sale it appeared that J. Ogden Armour’s faith and confidence in the revolutionary processes invented by the father and son Dubbs team paid off considerably. Bankers had scoffed at her for hanging on to the stock. With eight million dollars in hand she laughed right back at them.

Mrs. Armour wasn’t the only beneficiary. Carbon Petroleum Dubbs, having sold his stock in Jesse’s invention (along with the company’s sale), found himself $3,582,045 richer. Relieved that legalities were finally settled, C.P. was ready to get back to work – meaning “research and more research, perfecting the process of cracking oil.”6

The process had always been a family affair with Jesse and C.P. working side-by-side, stopping only when they were flat broke and forced to seek investors. In 1910 he had been a “wage earner” employed at an asphalt refinery. Now he was fabulously wealthy. C.P. was happy the company and its patents had been purchased by two large oil companies, saying “it is a wonderful thing for everyone involved and will be of immeasurable benefit to the oil industry as a whole.”7

He left Pittsburgh and moved to Wilmette, Illinois where he served as village president in 1933. In 1939 C.P. moved to Bermuda and built a home, although many winters were spent in Montecito, California. In 1959 he was named to the “Refining Hall of Fame”. C.P. and Bertha were the parents of three children: Jennie, Carbon Chatley and Bertha. Like his father and grandfather, Carbon Chatley Dubbs was an inventor, a chemical engineer by trade. One of his inventions was a concrete block made of pumice, later building his “dream home” entirely of concrete (including the roof).

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

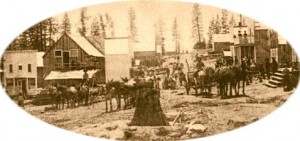

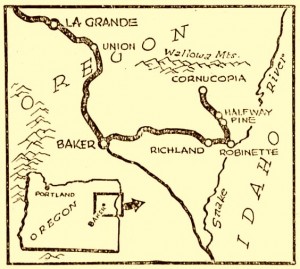

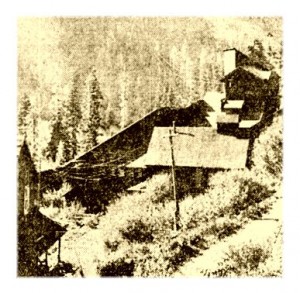

Ghost Town Wednesday: Cornucopia, Oregon

Gold was first discovered near the Idaho border in eastern Oregon in 1884 by Lon Simmons. The town of Cornucopia, which in Latin means “Horn of Plenty”, sprung up – said to have been named after the mining town of Cornucopia, Nevada. In July of 1885 five hundred men had already converged on Cornucopia, “quite a village”, reported the Morning Oregonian:

There is no doubt about the mines. They are very rich. Gold is being brought in every day and to see the rock is to be convinced that the mines are a big thing.8

Miners reported veins so rich that big nuggets would tumble right out of the rocks. Over the years sixteen mines produced 300,000 ounces of gold, although one source estimates that eighty percent of the gold ore body still remains.9

The early years from 1884 to 1886 produced the biggest gold booms, the town expanding with general stores, saloons, restaurants and hotels. However, unlike many other western mining towns, Cornucopia was a fairly tame place it seems with only a few killings (and suicides).

The early years from 1884 to 1886 produced the biggest gold booms, the town expanding with general stores, saloons, restaurants and hotels. However, unlike many other western mining towns, Cornucopia was a fairly tame place it seems with only a few killings (and suicides).

Cornucopia was situated in a mountain valley and known for its extremely harsh winters. During the winter of 1931-1932 one resident had kept meticulous records, indicating that by early March of 1932 over twenty-eight feet of snow had fallen. Massive slides were most common in the month of March as the snows began to melt.

In February of 1916 a snow slide buried a bunk house, but no injuries were reported after occupants were dug out. In January of 1923 a mother and her two children were killed when snow slide buried their home. The woman’s husband was thrown against a hot stove but survived.

The steep terrain required the use of aerial tramways and mining operations continued during the winter as weather permitted. You can find historic photos of the town and its epic snowstorms here.

Over the years fortunes of the mining operations rose and fell as the company went bankrupt, was sold, revived – and then repeated the cycle over again several times. In 1902, “the Cornucopia group of gold mines contains what is probably the largest ore body in the Pacific Northwest, if not in the United States”, according to the one newspaper.10

In the early 1900’s as many as seven hundred men were employed by the mining company. At its peak the mines were considered the sixth largest operation in the nation. Following yet another “fire sale” in early 1915, another gold strike was discovered in November. One newspaper made the following prediction:

The recent gold strikes in Cornucopia district, Baker county, have started a regular old fashioned rush to that old camp. The whole country is being staked out and some very rich ore is being uncovered. Some day a shaft or tunnel deep into old Greenhorn mountain on the line between Baker and Grant counties, is going to open up ore bodies that will make the old Comstock look to its laurels.11

In late 1921 a “lost vein” was discovered and the following year electricity was available and a twenty-stamp mill constructed, capable of producing up to sixty tons of ore per day.12 The mining company was again sold in early 1929, followed by rapid redevelopment. Then, of course, came the crash of 1929.

The 1930 census enumerated only ten people in Cornucopia, but by 1934 mining operations were starting up again after the decline. The following year mill tailings from cyanide-processed ore of years past was being converted into gold. In 1936 weekly wages for a workforce of between 100 and 125 miners totaled $15,000 with $8,000 per week expended for supplies.13

The 1930 census enumerated only ten people in Cornucopia, but by 1934 mining operations were starting up again after the decline. The following year mill tailings from cyanide-processed ore of years past was being converted into gold. In 1936 weekly wages for a workforce of between 100 and 125 miners totaled $15,000 with $8,000 per week expended for supplies.13

In July of 1936 all but fifteen of 175 miners struck for higher wages (one more dollar per day) and two paydays per month. By 1938 the company was touting its highest monthly profits ever – $100,000 in September of that year. 1939 was even more productive and Cornucopia mines were producing sixty-six percent of Oregon’s gold.

The 1940 census showed a significant increase in population from the last census: 10 in 1930 to 352 in 1940. Clearly, the mines were operating at peak capacity as the seventh largest operation in the United States. Despite this, operations were closed near the end of 1941. By early 1942 gold mining operations throughout the United States were ordered closed by President Roosevelt to concentrate the mining labor force on extracting war-related metals.

Following the war gold mining operations in some areas resumed, but Cornucopia was deemed a “war casualty”. The town had been largely abandoned. Today there are a few still-standing buildings and rusty machinery to see, but of course the best time to visit is during the summer.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Tombstone Tuesday: Thomas Jefferson Pilgrim

Thomas Jefferson Pilgrim was born on December 4, 1804 in East Haddam, Connecticut, the first child of eleven born to Thomas and Dorcas (Ransom) Pilgrim. His family were devout Baptists and T.J. Pilgrim would spend a lifetime devoted to religious education.

Thomas Jefferson Pilgrim was born on December 4, 1804 in East Haddam, Connecticut, the first child of eleven born to Thomas and Dorcas (Ransom) Pilgrim. His family were devout Baptists and T.J. Pilgrim would spend a lifetime devoted to religious education.

After receiving his license to preach Thomas entered Hamilton Literary and Theological Institute, part of Colgate University, at the age of eighteen. Even though his health was delicate he joined a group of sixty colonists and migrated to Texas following the completion of his education.

The migrants traveled to Cincinnati by water, via a raft built in two pieces and led by Elias R. Wightman. The first day was trouble-free although by that night they were cold and wet. After seeking shelter in an Indian village along the north bank, an old chief had pity and escorted them to a small cabin.

The migrants traveled to Cincinnati by water, via a raft built in two pieces and led by Elias R. Wightman. The first day was trouble-free although by that night they were cold and wet. After seeking shelter in an Indian village along the north bank, an old chief had pity and escorted them to a small cabin.

Although small (about twenty square feet), the cabin had a good floor and fireplace and the colonists had a warm place to sleep that night and food to eat. The raft trip continued past Pittsburgh and upon arrival in Cincinnati the migrants purchased provisions. Planning ahead in preparation for residing in Texas, Thomas bought a set of Spanish books so he could learn the language prior to arrival.

After waiting two weeks for a ship, a vessel from Maine run by three men became available for rental for a sum of five hundred dollars. However, it was determined only one of the crewmen proved capable of delivering the passengers to their destination. The captain instead offered to sell the vessel to the migrants for the same amount. The migrants agreed and set sail down the Mississippi River.

After reaching the open waters of the Gulf of Mexico, the boat began to drift due to a lack of breezes to move it along. Then a sudden gale arose and seasickness struck both passengers and crew. After two days of gale-force winds the waters calmed, only to see the storm-to-calm pattern repeat itself. Eventually they found their position to be near the entrance of Matagorda Bay, but with the wind blowing directly out of the pass there was little chance to enter safely. Still, they were determined to try and reach dry ground.

Thomas was the only person other than the boat’s crew who knew how to sail a vessel – it would be necessary later for Thomas to commandeer the vessel and later steer it into Matagorda Bay after the captain fell drunk. Provisions were also depleted and water was severely rationed – only one-half pint per person per day. At times Thomas declined his portion and instead offered it to the children.

Attempts to enter the bay were rebuffed by the winds for twenty-four hours before the vessel was steered toward Aransas. Upon landing, fires were started, water secured and an expedition sent out to find food. About an hour after reaching the shore (the boat was anchored about two hundred yards away) several canoes with Indians were seen.

The Karankawas were known to be cannibals and with only one musket at their disposal the women and children were especially vulnerable. As Thomas approached the Indians with the musket pointed toward the Indian leader, the chief motioned and made signs of friendship. The hunters arrived back making them feel safer still, although the Karankawas never showed any signs of unfriendliness. Instead, they traded the fish stored in their canoes to the weary and hungry migrants. After returning everyone to the boat the group remained anchored for several days while re-supplying food and water before setting sail once again.

With fair winds they again set sail with the intention to land at Matagorda. The captain handed the helm over to Thomas and went to his quarters to sleep. The wind was calm, however, and Thomas thought there was only a slight chance of landing. Since he had command of the vessel he informed Elias Wightman he could beach the boat, but the leader disagreed since it would require an expedition through Indian country before reaching a white settlement more than a hundred miles distant. Thus, it would be best to remain on the vessel.

Thomas awoke the captain who decided to again attempt to make it up the pass. Thomas and one of the crew members went ahead in a smaller boat and guided the larger vessel into the bay. Following a brief Christmas dinner Thomas set out for San Felipe de Austin in early 1829. Upon arrival he met Stephen F. Austin and the two established a friendship which lasted until Austin’s death in 1836. As a Latin scholar Thomas quickly learned Spanish and served as an interpreter and translator of Spanish documents for Austin.

In 1829 Thomas founded Austin Academy, a school for boys. That same year he also founded the first Sunday School in Texas. However, since Mexican government frowned on Protestant worship the Sunday School was soon closed. The migration from New York to Texas must have proven beneficial, at least according to an extracted letter published in a Hartford, Connecticut newspaper. In support of Dr. Phelps’ Compound Tomato Pills, T.J. Pilgrim of Columbia, Texas (of declining health for some time) wrote the following on December 31, 1838:

Having been here a sufficient length of time to test the merits of Dr. Phelps’ Tomato Pills, and the reception they are likely to meet – I feel it incumbent on me to send you the following: With regard to my own case, they have restored me to perfect health, after I thought health had forever fled; and from my experience, I am confident they are the best medicine yet discovered, for those diseases, to which in warm climates, we are more or less liable. They have been used also, by many others, in obstinate case of chill and fever, and have in every instance effected a radical cure.12

During the war with Mexico Thomas helped capture a Mexican boat in Matagorda Bay. For his service he received a Republic of Texas land grant in Gonzales County. In 1838 he married Lucy M. Ives and they moved to Gonzales where he began to organize a permanent school. Lucy died soon after their arrival, and following a Comanche raid plans for the school’s expansion were cancelled.

Thomas married Sarah Jane Bennett, daughter of Major Valentine Bennett, on April 13, 1841. After moving to Houston the couple later returned to Gonzales where they raised their family. Of their eleven children only five grew to maturity. Thomas and Sarah were charter members of the First Baptist Church of Gonzales.

From 1852 until 1853 he served on the board of visitors at Baylor University and also helped found Gonzales College, chartered on February 16, 1852. He served as president of the board of trustees of the college, in addition to civically serving his community as county treasurer and three terms as justice of the peace. He would also serve in the Confederate army.

T.J. Pilgrim is most remembered for his efforts to establish Sunday Schools in South Texas – “the cradle of Texas Baptist activity.”14 He is still celebrated as the “father of Sunday Schools in Texas”.

Thomas fell seriously ill in 1877, recovered enough to leave his bed in September, but passed away a few weeks later on October 29. He is buried in the Gonzales City Cemetery with Sarah who died on February 1, 1883. Their Greek Revival style home built in early 1877 still stands, located at 223 St. James Street in Gonzales.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Tombstone Tuesday: William Cobbledick

William D. Cobbledick was born in Whitley, Canada in 1849 and moved to Marshall, Michigan with his parents at the age of six months. While early records for William and his family are scarce, I believe his parents were John and Mary (Derbuiny?) Cobbledick. Other than the 1870 census the only other family record might have been one for Mary Cobbledick of St. Clair County whose name appears in an 1860 Federal Population Schedule index. There were other Canadian-born members of the Cobbledick family enumerated in St. Clair County, Michigan that year as well, but no John or William.

William D. Cobbledick was born in Whitley, Canada in 1849 and moved to Marshall, Michigan with his parents at the age of six months. While early records for William and his family are scarce, I believe his parents were John and Mary (Derbuiny?) Cobbledick. Other than the 1870 census the only other family record might have been one for Mary Cobbledick of St. Clair County whose name appears in an 1860 Federal Population Schedule index. There were other Canadian-born members of the Cobbledick family enumerated in St. Clair County, Michigan that year as well, but no John or William.

In fact, there seems to have been a large contingent of the Cobbledick family members who had migrated to America as evidenced by compiled census records at Ancestry.com. The surname originated in England, but as of 2014 only 737 people in the entire world bore the name (South Africa – 274; Australia – 156; England – 151; Canada – 83; United States – 72; Latvia – 1).15

The Internet Surname Database notes the surname and its various spellings include: Cobbledick, Cobledike, Cobbleditch, Copleditch, Copeldick, Cuppleditch (perhaps) and Cobberduke (now extinct). The name may have been locational, perhaps derived from a region of East Anglia and referring to ditch or dike/dyke built of cobble. Cobble was an early form of construction used in Norfolk and Suffolk.

The Internet Surname Database notes the surname and its various spellings include: Cobbledick, Cobledike, Cobbleditch, Copleditch, Copeldick, Cuppleditch (perhaps) and Cobberduke (now extinct). The name may have been locational, perhaps derived from a region of East Anglia and referring to ditch or dike/dyke built of cobble. Cobble was an early form of construction used in Norfolk and Suffolk.

Charles Bardsley, a leading Manchester minister, published Our English Surnames in 1873 and later claimed the name meant “Cobbalds dyke” – Cobbald was an early first name.16 The Dictionary of English and Welsh Surnames, also by Bardsley and published in 1901 by his widow, emphatically stated, however, the name had no connection to a dike made of cobble-stones, but rather to a proprietor named Cobbold. One newspaper article, musing about a litany of unusual surnames, noted: “Cobbledick, who should be a shoemaker”.17

It’s possible William’s parents had already passed away by the 1870 census when he was enumerated as a farm laborer with a Calhoun County family. At the age of nineteen William had his first taste of the “big village” when he traveled to Kalamazoo to attend a fair. While there he purchased a pair of rather uncomfortable custom-made boots. On his way home William removed the boots and continued walking barefoot. In later years William, or “Uncle Bill” as he was called, still preferred walking to riding – and he still had the boots.

He loved the outdoors and spent most his life there hunting, fishing and learning to swim in the Kalamazoo River. On January 1,1872 William married Ida Marie Knickerbocker – Ida Marie Knickerbocker Cobbledick (I had to giggle a little when I saw that name at Find-A-Grave – what a name!). I giggled again when I saw their marriage record where Ida’s name is written as “Ida Maria Roderdicker”.

Their first child, a son named Charles, was born in 1873. Other children mentioned in later newspaper articles were Marietta (1878) and Ada May (1887). William and Ida remained in Marshall until about 1879 and then spent several years living in Allegan and Van Buren counties before moving back to Kalamazoo County. Ida passed away on December 23, 1917 and Charles died in Lubbock, Texas in May of 1922.

William remained vigorously active following Ida’s death. In April of 1922 it was noted the “widely known resident of Kalamazoo county fell[ed] and split sixty cords of wood during [the] past winter.”18 The article headline read:

Uncle Bill Cobbledick is Champion Woodsman at 74

He was seventy-four “years young” and continued to tramp off to the north woods every fall to hunt deer, “seldom returning without his limit of game.” William loved to hunt and fish more than eat when he was hungry, he declared. He was still a great walker and often walked three-and-a-half miles to Alamo Center.

According to a Michigan death record William D. Cobbledick died on July 2, 1926 at the age of seventy-seven in Kalamazoo, although his tombstone has “1927″ as his year of death. He is buried with Ida and two of his children (Charles and Marietta) in Oakwood Cemetery in what appears to be a family plot.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Far-Out Friday: Gravesite Dowsing: Science, Wizardry, Witchcraft or Just Plain Hooey?

October is the spookiest month of the year, so a story about gravesite dowsing seemed in order for Halloween Eve-Eve, I guess you could call it. The article title pretty much encompasses the range of opinion regarding the subject, although I have to say a brief survey I conducted most decidedly leaned toward the “just plain hooey” side.

October is the spookiest month of the year, so a story about gravesite dowsing seemed in order for Halloween Eve-Eve, I guess you could call it. The article title pretty much encompasses the range of opinion regarding the subject, although I have to say a brief survey I conducted most decidedly leaned toward the “just plain hooey” side.

Since, personally, I don’t really have an opinion (yet) one way or the other, I hope nonetheless you’ll find the article objective, informative, balanced — and hopefully interesting! And oh, please do tell me what you think — science, wizardry, witchcraft or just plain hooey?

Since, personally, I don’t really have an opinion (yet) one way or the other, I hope nonetheless you’ll find the article objective, informative, balanced — and hopefully interesting! And oh, please do tell me what you think — science, wizardry, witchcraft or just plain hooey?

This article has been removed from the blog, but will be included in the September-October 2019 issue of our digital publication — Digging History Magazine. Speaking of spooky, the October 2018 issue of the magazine was especially so — murder, strange lights, UFOs, American poltergeist and more! Video preview here.

This article has been removed from the blog, but will be included in the September-October 2019 issue of our digital publication — Digging History Magazine. Speaking of spooky, the October 2018 issue of the magazine was especially so — murder, strange lights, UFOs, American poltergeist and more! Video preview here.

Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads, just carefully-researched stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? That’s easy if you have a minute or two. Here are the options (choose one):

- Scroll up to the upper right-hand corner of this page, provide your email to subscribe to the blog and a free issue will soon be on its way to your inbox.

- A free article index of issues is available in the magazine store, providing a brief synopsis of every article published in 2018. Note: You will have to create an account to obtain the free index (don’t worry — it’s easy!).

- Contact me directly and request either a free issue and/or the free article index. Happy to provide!

Thanks for stopping by!

Feisty Female Sheriffs: Claire Helena Ferguson, in her own words

This headline introduced some fearless and celebrated women to the readers of the Milwaukee Journal in 1899: “What Man Has Done Women Can Do”. The author had written a recent article “about dependence being an old fashioned virtue and that the clinging ivy type of women were no longer considered the highest ideal.”19. Exhibit number one for the premise of her article was one of the most celebrated women of that time, Miss Claire Helena Ferguson.

This headline introduced some fearless and celebrated women to the readers of the Milwaukee Journal in 1899: “What Man Has Done Women Can Do”. The author had written a recent article “about dependence being an old fashioned virtue and that the clinging ivy type of women were no longer considered the highest ideal.”19. Exhibit number one for the premise of her article was one of the most celebrated women of that time, Miss Claire Helena Ferguson.

Did you enjoy this article snippet? Want to know more? This article has been updated with new research and published in the November-December 2019 issue of Digging History Magazine. The magazine is on sale in the Digging History Magazine store and features these stories:

Did you enjoy this article snippet? Want to know more? This article has been updated with new research and published in the November-December 2019 issue of Digging History Magazine. The magazine is on sale in the Digging History Magazine store and features these stories:

- The Burr Conspiracy: Treason or Prologue to War

- Finding War of 1812 Records (and the stories behind them)

- Sarah Connelly, I Feel Your Pain (Adventures in Research: 1812 Pension Records)

- Essential Skills for Genealogical Research: Noticing Notices

- Bullets, Battles and Bands: The Role of Music in War

- Feisty Female Sheriffs: Who Was First?

- The Dash: Bigger Family: (A Bigger and Better Story)

- Book reviews, research tips and more

Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 85-100+ pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 85-100+ pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Tombstone Tuesday: Joseph Faubion, the man who “died twice”

Joseph Faubion was born in Clay County, Missouri on September 7, 1842 to parents Moses and Nancy (Hightower) Faubion. Moses was first married to Patsy Holcomb, and after she died he married Nancy Hightower in 1841. According to the 1850 census Nancy was nineteen years younger than Moses and Joseph appears to have been their first child.

Joseph Faubion was born in Clay County, Missouri on September 7, 1842 to parents Moses and Nancy (Hightower) Faubion. Moses was first married to Patsy Holcomb, and after she died he married Nancy Hightower in 1841. According to the 1850 census Nancy was nineteen years younger than Moses and Joseph appears to have been their first child.

This article is no longer available for free at this site. It was re-written and enhanced, complete with footnotes and sources and has been published in the October 2018 issue of Digging History Magazine. This was a “spooky” issue with articles including, “American Poltergeist (and other strange goings-on)”, “Sister Amy’s Murder Factory”, “Those Dang Saucers Appear Everywhere”, and more. Should you prefer to purchase the article only, contact me for more information.

This article is no longer available for free at this site. It was re-written and enhanced, complete with footnotes and sources and has been published in the October 2018 issue of Digging History Magazine. This was a “spooky” issue with articles including, “American Poltergeist (and other strange goings-on)”, “Sister Amy’s Murder Factory”, “Those Dang Saucers Appear Everywhere”, and more. Should you prefer to purchase the article only, contact me for more information.

I invite you to check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!