Military History Monday: Hundred Days Men

By 1864 it was becoming increasingly more difficult to conscript enough able-bodied men to fight for either the North or South. Before the war began in early April of 1861, the United States Army had around 16,400 officers and men. On April 9, 1861 a call was made for the District of Columbia to muster ten companies of militia. There was some resistance as evidenced by one company of 100 men: two officers, one sergeant, one corporal, one musician and ten privates refused to muster.

By 1864 it was becoming increasingly more difficult to conscript enough able-bodied men to fight for either the North or South. Before the war began in early April of 1861, the United States Army had around 16,400 officers and men. On April 9, 1861 a call was made for the District of Columbia to muster ten companies of militia. There was some resistance as evidenced by one company of 100 men: two officers, one sergeant, one corporal, one musician and ten privates refused to muster.

Less than a week later, President Lincoln called for 75,000 militiamen to serve three months. By May he was calling for 500,000 to serve three years. In 1862 there were calls for 300,000 to serve three years and later that year another 300,000 to serve for nine months. As the war continued unabated, calls for more enlistments were issued. Some would re-enlist after their term of service had expired. Even with a large numbers of troop already assembled, Lincoln made a special plea in 1863 and 1864, first to Maryland, Pennsylvania, Ohio and West Virginia.

Less than a week later, President Lincoln called for 75,000 militiamen to serve three months. By May he was calling for 500,000 to serve three years. In 1862 there were calls for 300,000 to serve three years and later that year another 300,000 to serve for nine months. As the war continued unabated, calls for more enlistments were issued. Some would re-enlist after their term of service had expired. Even with a large numbers of troop already assembled, Lincoln made a special plea in 1863 and 1864, first to Maryland, Pennsylvania, Ohio and West Virginia.

This article is no longer available for free at this site. It was re-written and enhanced, complete with footnotes and sources and has been published in the April 2018 issue of Digging History Magazine. Should you prefer to purchase the article only, contact me for more information.

This article is no longer available for free at this site. It was re-written and enhanced, complete with footnotes and sources and has been published in the April 2018 issue of Digging History Magazine. Should you prefer to purchase the article only, contact me for more information.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Surname Saturday: Bliss

Bliss

The Bliss surname is believed to have been brought to England during the migration following the Norman Conquest of 1066, possibly a reference to Blois in the Loir-et-Cher region of France. Another place which might be connected to this surname was “Bleis,” located in a region of northwest France, and recorded in 1077.

Families with this surname settled primarily in Leicestershire and Worcestershire, England. Some sources believe the village of Stoke Bliss in Worcestershire was named after the Norman family “de Blez,” notably William de Blez. One home owned by William de Blez in the twelfth century was known as “Stok in Herfordshire,” which then became “Stoke de Blez” and later “Stoke Bliss.” Similiarly, a manor in Staunton on Wye was first named after its landlords “de Bleez” or “de Blees”.

Another source, P.H. Reaney, author of Dictionary of British Surnames, believes the name was either derived from the de Blez family of Normandy or the Middle English noun “blisse,” which of course means joy or gladness. Recorded spelling variations include “Bliss”, “Bleys”, “Blois”, “Bloys”, “Bloiss”, “Blisse”, “Blysse” to name a few.

Thomas Bliss

Thomas, son of Thomas Bliss, Sr., was born in 1583. Like so many who came to New England in the early seventeenth century, Thomas Bliss, Sr. and his family were persecuted for their staunch Puritan faith. After King Charles I re-assembled both Houses of Parliament in early 1628, his sons Jonathan and Thomas, Jr. traveled to London to view the proceedings and to confront Archbishop Laud, one of their persecutors. According to family historian John Homer Bliss, they “remained sometime in the city, long enough at least for Charles’ officers and spies to learn their names and condition, and whence they came; and from that time forth they, with others who had come to London on the same errand, were marked for destruction.”

For their non-conformity they were fined a thousand pounds and imprisoned for several weeks. The elder Thomas was dragged through the streets, and officers of the High Commission also seized their livestock. The three sons of Thomas, Sr., along with twelve other men, were paraded through the marketplace with ropes around their necks, and Jonathan and Thomas, Sr. were thrown in prison.

For their non-conformity they were fined a thousand pounds and imprisoned for several weeks. The elder Thomas was dragged through the streets, and officers of the High Commission also seized their livestock. The three sons of Thomas, Sr., along with twelve other men, were paraded through the marketplace with ropes around their necks, and Jonathan and Thomas, Sr. were thrown in prison.

After enduring intense and relentless persecution, Thomas, Jr. and his other brother George, decided to immigrate to New England. Jonathan aspired to go but his physical health had been significantly weakened due to long imprisonments and damp, unhealthy prison cells; he died without ever seeing America. Jonathan’s son Thomas immigrated in 1636 and joined his uncle who had settled on the south side of Boston Bay. Thomas and his family soon made their way to the Hartford settlement. They were farmers and some of the first original land owners of Hartford. Thomas had several children by his two wives: Thomas, Ann, Sarah, Nathaniel, Mary, Lawrence, Hannah, John, Samuel and twins Hester and Elizabeth, all born in England except the last three.

His daughter Mary married Joseph Parsons, who later became one of the wealthiest men in Northampton, Massachusetts, in 1646. Mary Bliss Parsons, however, had anything but a blissful life – she was accused of witchcraft … repeatedly!

Mary Bliss Parsons

Joseph and Mary Parsons lived for a time in Springfield after their marriage but in 1654 moved to Northampton. Even before the couple married, Joseph had set himself on the path to prosperity and wealth, perhaps due to trading with the Indians. Not yet thirty years old he had already served in various local offices and attained a stature not usually accorded someone of his age.

After arriving in Northampton Joseph continued to prosper as a merchant. He worked with the Pynchon family (perhaps kin of his) who were the principle fur traders in that area, a chartered monopoly actually. He eventually opened a store in Northampton, along with other enterprises such as a grist and saw mill and was licensed to sell liquor. With wealth and success, however, came legal entanglements and Joseph was often in court, suing or being sued.

Some cases involved debt settlement or enforcement of covenants and contracts, but some were of a more serious nature. From Entertaining Satan: Witchcraft and the Culture of New England by John Putnam Demos:

In 1664, for example, he was presented and “admonished” in court for his “lascivious carriage to some women of Northampton.” A few months later he was fined £5 for his “high contempt of authority” in resisting a constable’s efforts to attach some of his property in another case. (Witnesses reported some “scuffling in the business, whereby blood was drawn between them.” Joseph publicly acknowledged his offence, and the court abated part of his fine.) A year later Joseph was fined again “for contemptuous behavior toward the Northampton commissioners and toward the selectmen, and for disorderly carriage when the company were about the choice of military officers.” These cases suggest something of his character and personal style. Defined by his own achievements as a man of authority, Joseph did not easily brook the authority of others. Energetic, shrewd, resourceful as he evidently was, he displayed a rough edge in dealings with others. He was, on all these grounds, a figure to be reckoned with.

Mary, of course, shared in the fruits of her husband’s business acumen and success. Tradition holds that she was remembered in her town as being “possessed of great beauty and talents, but . . . not very amiable . . . exclusive in the choice of her associates, and . . . of haughty manners.” The attributes of “not very amiable” and “of haughty manners” could have been assigned to her as a result of dealings in her own lawsuits and trials for the crime of witchcraft.

Mary had twelve pregnancies (two sets of twins), fourteen delivered and named, and nine children raised to adulthood. Perhaps with her husband’s wealth and success and her own success at bearing and raising children, she was envied by some in her community. At least one source speculates that the community began to circulate rumors of witchcraft, assuming that her husband’s success came as a result of such activity.

One of Mary’s primary accusers, Sarah Bridgeman, was sued by Joseph for slander in 1656. Some believe that Sarah was envious of the Parsons’ success. Sarah’s testimony included her assertion that any time a disagreement or argument had ensued with Mary Parsons or her family, the Bridgeman family would experience some unfortunate and unexpected event such as livestock contracting a fatal disease and dying. In Sarah’s mind, it was Mary’s way of exacting revenge apparently. Sarah also blamed Mary for an injury one of her children sustained, and even the loss of her infant son. This is what Sarah imagined and testified to in court:

I [Sarah] being brought to bed, about three days after as I was sitting up, having the child in my lap, there was something that gave a great blow on the door. And that very instant, as I apprehended, my child changed. And I thought with myself and told my girl that I was afraid my child would die…Presently… I looking towards the door, through a hole…I saw…two women pass by the door, with white clothes on their heads; then I concluded my child would die indeed. And I sent my girl out to see who they were, but she could see nobody, and this made me think there is wickedness in the place.

That must have seemed a bit far-fetched and the court agreed. Sarah’s husband James was ordered to pay a fine of £10 and court costs. Sarah was required to make a public apology. After so convincing a verdict, one would think the matter was settled. However, rumors and accusations persisted for several years. In 1674 Mary was again accused, but this time she was the defendant, and as you might guess, the aggrieved party was the Bridgeman family.

The Bridgeman’s daughter, Mary Bartlett, had died suddenly in August of 1674. She left behind her husband Samuel and an infant son. Samuel Bartlett and James Bridgeman were convinced, and testified to same, that “she came to her end by some unlawful and unnatural means … by means of some evil instrument.” Who else to blame but Mary Parsons?

The trial began on September 29 and Mary no doubt defended herself vigorously. According to Annals of Witchcraft in New England:

The Substance of her Speech was, that “she did assert her own Innocency, often mentioning how clear she was of such a Crime, and that the righteous God knew her Innocency, and she left her Cause in his Hand.”

The court wasn’t convinced yet of her innocence and they “appointed a Jury of soberdized, chaste Women to make diligent Search upon the Body of Mary Parsons, whether any Marks of Witchcraft appear, who gave in their Account to the Court on Oath, of what they found.” Whether or not any evidence was found is not known, but the court deferred action twice until on January 5, 1675 the case was reconvened. Further testimony was held, and curiously, Mary’s son John was accused of witchcraft as well, but dismissed without cause.

Mary was bound over for another appearance in March, secured by a bond of £50 which was paid by Joseph. At the March court appearance, Mary was indicted by the grand jury and ordered to prison until the official trial in May. On May 13, 1675 the official indictment was again read:

. . . in that she had, not having the Fear of God before her Eyes, entered into Familiarity with the Devil, and committed sundry Acts of Witchcraft on the Person or Persons of one or more.

Mary pleaded not guilty and was cleared by the jury. It’s not likely that Mary Bliss Parsons ever escaped the accusations hurled against her for years. Some believe that perhaps she was once again accused in 1679 although there don’t appear to be any records to corroborate that theory. In 1679 or 1680 the Parson family moved back to Springfield, where Joseph died in 1683. He left behind an impressive estate of £2,088. Mary passed away in January of 1712.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

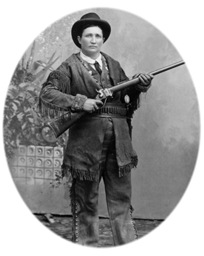

Feisty Females: Martha Jane Canary, a.k.a. “Calamity Jane”

Many stories have been written about today’s “feisty female”, but if based on her short autobiography, it’s debatable whether they are true or not. Generally speaking, she was known for her “wild side” and it was legendary, based on the numerous stories in newspapers across the country beginning in the mid-1870s. Legends of America describes her like this:

Many stories have been written about today’s “feisty female”, but if based on her short autobiography, it’s debatable whether they are true or not. Generally speaking, she was known for her “wild side” and it was legendary, based on the numerous stories in newspapers across the country beginning in the mid-1870s. Legends of America describes her like this:

she … [grew] up to look and act like a man, shoot like a cowboy, drink like a fish, and exaggerate the tales of her life to any and all who would listen.

The Encyclopedia Britannica backs up that observation: “The facts of her life are confused by her own inventions and by the successive stories and legends that accumulated in later years.”

Martha Jane Canary, a.k.a. “Calamity Jane” was born near Princeton, Missouri on May 1, 1852 to parents Robert and Charlotte. Martha was the oldest of six children. Her father, a farmer, moved the family to Virginia City, Montana in 1865.

Martha Jane Canary, a.k.a. “Calamity Jane” was born near Princeton, Missouri on May 1, 1852 to parents Robert and Charlotte. Martha was the oldest of six children. Her father, a farmer, moved the family to Virginia City, Montana in 1865.

In her short autobiographical sketch (written for publicity purposes in 1896), Martha wrote (or dictated – she may have been illiterate) that she spent the majority of the five-month trip with the men of the party – she boasted that hunting, scouting and fording streams provided more excitement and adventure. A sampling of her exploits:

Many times in crossing the mountains the conditions of the trail were so bad that we frequently had to lower the wagons over ledges by hand with ropes for they were so rough and rugged that horses were of no use. We also had many exciting times fording streams for many of the streams in our way were noted for quicksands and boggy places, where, unless we were very careful, we would have lost horses and all. Then we had many dangers to encounter in the way of streams swelling on account of heavy rains. On occasions of that kind the men would usually select the best places to cross the streams, myself on more than on occasion have mounted my pony and swam across the stream several times merely to amuse myself and have had many narrow escapes from having both myself and pony washed away to certain death, but as the pioneers of those days had plenty of courage we overcame all obstacles and reached Virginia City in safety.

Her mother died at Black Foot, Montana in 1866, before the family reached its destination, and was buried there. Martha and her remaining family departed sometime during the spring of that year and headed to Utah where she remained until her father died in 1867. She doesn’t mention it in her “memoir” but it’s possible she was in charge of her siblings, being the oldest child. Her life is so sketchy and often misrepresented (primarily by her own account) it’s difficult to determine. In the July-August 2003 edition of the American Cowboy magazine, the article speculates that her siblings were adopted by Mormon families while she began her career as a wild-west drifter.

By that time she was an attractive fifteen-year old young woman, who chose to dress in men’s clothes, pulling her hair up under a big hat and further taking on the appearance of a man or older boy. If her own self-proclaimed exploits are to be believed, she worked for the Union Pacific Railroad, an ox cart driver for the Army, wagon train packer and mule skinner. It’s likely she worked whatever job she could find including dishwasher, cook, nurse, and some say prostitute.

After departing Utah, with or without siblings, she headed to Fort Bridger, Wyoming. In 1870 she claimed to have joined up with General Custer’s outfit as a scout. She remarked, “[W]hen I joined Custer I donned the uniform of a soldier. It was a bit awkward at first but I soon got to be perfectly at home in men’s clothes.”

After wintering in Arizona in 1871, she returned to Wyoming to serve during the Army’s engagement with the Nez Perce – or “Nursey Pursey” as she called them in her memoir. During that campaign she earned her sobriquet, “Calamity Jane”. Her version of the event:

It was during this campaign that I was christened Calamity Jane. It was on Goose Creek, Wyoming, where the town of Sheridan is now located. Capt. Egan was in command of the Post. We were ordered out to quell an uprising of the Indians, and were out for several days, had numerous skirmishes during which six of the soldiers were killed and several severely wounded. When on returning to the Post we were ambushed about a mile and a half from our destination. When fired upon Capt. Egan was shot. I was riding in advance and on hearing the firing turned in my saddle and saw the Captain reeling in his saddle as though about to fall. I turned my horse and galloped back with all haste to his side and got there in time to catch him as he was falling. I lifted him onto my horse in front of me and succeeded in getting him safely to the Fort. Capt. Egan on recovering, laughingly said: “I name you Calamity Jane, the heroine of the plains.”

American Cowboy indicated that the Captain said, “Jane, you’re a wonderful little woman to have around in a time of calamity.” One other version speculates she was given the name by the editor of the Laramie Boomerang – for her presence at various calamities in the form of shootouts and street brawls.

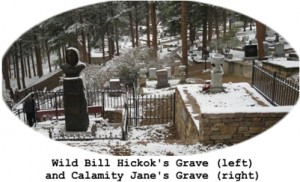

After a brief illness in 1876 while serving with General Crook (who was on his way to join Custer at the Little Bighorn), she headed instead to Fort Laramie where she became acquainted with James Butler “Wild Bill” Hickok. The two of them then traveled together to Deadwood, South Dakota.

Some historians surmise that Jane and Hickok had a romantic relationship. If you go to her entry on the Find-A-Grave web site, someone has created that illusion, linking to his entry as her spouse, as well as them having a child together. However, another friend of Wild Bill’s, “Colorado Charley” Utter, declared that “Wild Bill would have died rather than share a bed with Jane.” She was also rumored to have been a friend of the mysterious and exotic Eleanore Dumont, a.k.a. “Madame Moustache.”

After arriving in Deadwood, she worked as a Pony Express rider between Deadwood and Custer. On August 2, 1876, Hickok was gambling at a saloon when he was shot in the back of the head by Jack McCall. McCall would later claim that he was avenging the killing of his brother in Abilene, Kansas at the hand of Wild Bill. The jury found McCall innocent of the charge of murder. McCall left for Wyoming but just a short time later it was determined that the Deadwood trial had no legal basis since it was located in Indian Territory. He was re-arrested in Laramie on August 29, charged with murder and transported to Yankton, South Dakota to be re-tried. This time he was found guilty and hanged.

Calamity Jane’s version is “somewhat” different:

On the 2nd of August, while setting at a gambling table in the Bell Union saloon, in Deadwood, he was shot in the back of the head by the notorious Jack McCall, a desperado. I was in Deadwood at the time and on hearing of the killing made my way at once to the scene of the shooting and found that my friend had been killed by McCall. I at once started to look for the assassin and found him at Shurdy’s butcher shop and grabbed a meat cleaver and made him throw up his hands; through the excitement on hearing of Bill’s death, having left my weapons on the post of my bed. He was then taken to a log cabin and locked up, well secured as every one thought, but he got away and was afterwards caught at Fagan’s ranch on Horse Creek, on the old Cheyenne road and was then taken to Yankton, Dakota, where he was tried, sentenced and hung.

She remained in Deadwood working the mining camps surrounding the area. When a smallpox plague broke out she helped to nurse people back to health, so she had a tender side. She, however, was still rough around the edges and a brawler who hung out with gunslingers and other disreputable characters.

Another one of her legendary exploits occurred in 1877 while she was riding to Crook City. She came upon a stagecoach that was being pursued by Indians. As she pulled alongside the stagecoach she noticed that the driver was “lying face downwards in the boot of the stage,” having been mortally wounded by the Indians. After the coach pulled up to a station, she took over the reigns of the coach and continued onto Deadwood with the six passengers and the dead driver.

By the mid-to-late 1870’s, Calamity Jane was beginning to make a name for herself, or at least by the legend of her exploits. Her name began to appear in newspapers beginning as early as 1875. Here, though, it’s still difficult to separate fact from fiction. One of the first newspaper accounts I found was in the Chicago Daily Tribune on June 19, 1875, declaring that hers was the same old, old story:

By the mid-to-late 1870’s, Calamity Jane was beginning to make a name for herself, or at least by the legend of her exploits. Her name began to appear in newspapers beginning as early as 1875. Here, though, it’s still difficult to separate fact from fiction. One of the first newspaper accounts I found was in the Chicago Daily Tribune on June 19, 1875, declaring that hers was the same old, old story:

Calamity was a few years ago the respectable proprietress of a millinery store in Omaha. Calamity was good looking, and yielding to drink she soon became a homeless outcast, and as a natural result found herself out on the frontier repenting for a few months, and hiring out to do housework, then being found out, returning to her vicious life, until the next periodical fit of repentance came on.

Nevertheless, she seemed to be, at least in the minds of newspaper readers, whatever the newspaper chose to report, true or not. She apparently roamed all over the West for several years. In 1882 she took up ranching near the Yellowstone River and ran a “way side inn”. She vacated the ranch the following year and went to California, later traveling back to Utah and then back to San Francisco in 1884. In the summer of 1884 she headed to Texas, arriving in El Paso sometime in the fall. There she met Clinton Burke, a native Texan, and the two were married in August 1885. She gave birth to a baby girl on October 28, 1887.

She and her family left Texas in 1889 and moved to Boulder, Colorado where they ran a hotel. In 1893 the Burkes were again on the move, traveling throughout the West: Wyoming, Montana, Idaho, Washington, Oregon and South Dakota. Her notoriety, and her exploits breathlessly reported across the country, must have gained her respect and awe through the years. I found one short obituary in the Council Grove Republican (Kansas) for a young child:

Died in Cowley county – the place of her birth – Calamity Jane, only child of Adversity Greenback and Calamity Howler. The child was only two years old, and died of that dreadful, dire, depressing disease, wind colic.

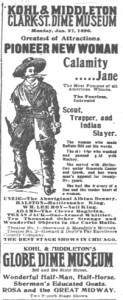

After meeting an agent of the Kohl & Middleton Dime Museum, she came under their management, promoted as the “Greatest of Attractions: Pioneer New Woman”. At some point, I believe she and her husband must have parted ways. American Cowboy reported that the two divorced and her child was raised in a convent. Here too, it is debatable as to what really happened – some accounts claim she was married as many as a dozen times!

At some point, perhaps as early as 1893, she worked for William “Buffalo Bill” Cody’s Wild West Show as a storyteller and sharpshooter. She was still drinking and carousing freely, however, and was later fired. She found a place to sober up only to return to the bottle and brawling. In early 1901, newspapers were reporting her plight when she was admitted to the Gallatin County (Montana) Poorhouse:

At some point, perhaps as early as 1893, she worked for William “Buffalo Bill” Cody’s Wild West Show as a storyteller and sharpshooter. She was still drinking and carousing freely, however, and was later fired. She found a place to sober up only to return to the bottle and brawling. In early 1901, newspapers were reporting her plight when she was admitted to the Gallatin County (Montana) Poorhouse:

Apparently she found a benefactress, however, who was willing to help. Mrs. Josephine Windfield Brake of Buffalo, New York came to her rescue after finding Jane in “the hut of a negress at Horr, near Livingstone” (Montana). Mrs. Brake, an author and correspondent for a New York newspaper, had heard of Calamity’s plight. Headlines proclaimed that Jane liked the change and would spend the remainder of her days in comfort – except that isn’t how it played out.

Apparently she found a benefactress, however, who was willing to help. Mrs. Josephine Windfield Brake of Buffalo, New York came to her rescue after finding Jane in “the hut of a negress at Horr, near Livingstone” (Montana). Mrs. Brake, an author and correspondent for a New York newspaper, had heard of Calamity’s plight. Headlines proclaimed that Jane liked the change and would spend the remainder of her days in comfort – except that isn’t how it played out.

She made her way back West after her job at the Pan American Exposition (World’s Fair) in Buffalo didn’t work out. She had been working a rather sedate job selling books and receiving a commission. When she became suspicious of her share of the profits, she decided to join the Midway instead. One night she went on a drunken spree and tried to shoot up the whole Midway, which landed her in jail.

By the summer of 1903 she had arrived back in South Dakota. In January of that year she had gone on a rampage, as the Waterloo Press headline proclaimed: “Takes a Freak and ‘Shoots Up’ Town of Sheridan, Wyo.” After arriving in Sheridan she had begun to “load up with liquid enthusiasm.” Next on her agenda was “shooting up the town.” When her ammunition supply was spent, the town marshal put her on a train and sent her on her way. The newspaper noted that although she had been taken in by a Buffalo woman, “the life of an eastern city was too tame for a woman who had fought Indians and ‘plains’ whisky for years.”

After arriving back in South Dakota, she was taken in by Madam Dora DuFran, proprietor of a brothel in Belle Fourche. There Jane worked as a laundress and cook. In early August she was living in a small room in Terry, near Deadwood, and on August 2, 1903, Calamity Jane died. The Cincinnati Enquirer reported that her last dying request, despite having had twelve husbands, was “that she be allowed to sleep by the side of the man she first loved” – Wild Bill Hickok.

The Enquirer also reported that she had “sent her daughter away for her own good.” Her friends begged her, during her last days, to reveal her daughter’s name but she refused – “Let her be,” she said. The newspaper speculated that the cause of Calamity’s decline and eventual demise was that during her fifty-one years, the “real Wild West was born and died. Its passing left her forlorn.”

The Enquirer also reported that she had “sent her daughter away for her own good.” Her friends begged her, during her last days, to reveal her daughter’s name but she refused – “Let her be,” she said. The newspaper speculated that the cause of Calamity’s decline and eventual demise was that during her fifty-one years, the “real Wild West was born and died. Its passing left her forlorn.”

She may have been a rough-and-tumble character, but the Enquirer reported that through those years she retained two “womanly traits”:

While she might be drunk one day and chasing Indians over the prairie another, she never missed an opportunity to put on skirts and diamonds at a dance. The next morning she would be ready for a trip with the Government mail, or perhaps would be cracking the bottles in a saloon with well aimed bullets. But she would stop abruptly even the incomparable pleasure of “shooting-up” a saloonful of miners bristling with guns, if some one should report a case of sickness. She never refused to go even great distances to nurse the sick back to health.

If one can manage to separate fact from fiction, such was the legend of Martha Jane Canary, a.k.a. “Calamity Jane.”

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

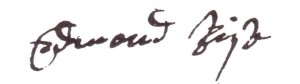

Wild Weather Wednesday: The Great Flood of 1913 (Part Two)

By the morning of March 24, headlines reported news of the first devastating wave of weather that had first impacted Omaha, Nebraska (see last week’s article). A tornado later roared through Terra Haute with at least two dozen killed. Even though the articles reported at least ninety dead in Omaha and twenty-four in Terra Haute, the headlines proclaimed HUNDREDS KILLED:

By the morning of March 24, headlines reported news of the first devastating wave of weather that had first impacted Omaha, Nebraska (see last week’s article). A tornado later roared through Terra Haute with at least two dozen killed. Even though the articles reported at least ninety dead in Omaha and twenty-four in Terra Haute, the headlines proclaimed HUNDREDS KILLED:

Nebraska, Missouri, Iowa, Illinois, Indiana, Michigan and Oklahoma had already been affected by the storm. By the time newspapers hit the streets on the 25th the death toll was being reported to have risen to 225 with over 750 injured. Damage estimates for Omaha were thought to be at least twelve million dollars.

Nebraska, Missouri, Iowa, Illinois, Indiana, Michigan and Oklahoma had already been affected by the storm. By the time newspapers hit the streets on the 25th the death toll was being reported to have risen to 225 with over 750 injured. Damage estimates for Omaha were thought to be at least twelve million dollars.

The first story of flooding appeared on the 25th as well. After the tornado, Terra Haute was inundated with rain and flooding which caught both rural and city dwellers by surprise. Residents were already fleeing their homes as the flood waters surged. Thousands of acres of land were underwater with rivers and creeks out of their banks and levees breached. To prevent looting, the State Militia began boat patrols in devastated areas.

The first story of flooding appeared on the 25th as well. After the tornado, Terra Haute was inundated with rain and flooding which caught both rural and city dwellers by surprise. Residents were already fleeing their homes as the flood waters surged. Thousands of acres of land were underwater with rivers and creeks out of their banks and levees breached. To prevent looting, the State Militia began boat patrols in devastated areas.

This article is no longer available on this web site. It will be re-written and enhanced with footnotes and sources in a future issue of Digging History Magazine. I invite you to check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

This article is no longer available on this web site. It will be re-written and enhanced with footnotes and sources in a future issue of Digging History Magazine. I invite you to check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Tombstone Tuesday: Henry Collis and Zipporah Chandler Rice – Sodom Laurel, NC

Henry Collis and Zipporah (Chandler) Rice were both born and raised, lived and died, in Madison County, North Carolina in the heart of Appalachia. They are both buried in Rice Cove, a family cemetery. Their ancestors came from England, perhaps some from Scotland. Folklorist Bascom Lamar Lundsford called Madison County “the last stand of the natural people.” In 1917, ethnomusicologist Cecil Sharp described life in Madison County in his book English Folk Songs from the Southern Appalachians:

Henry Collis and Zipporah (Chandler) Rice were both born and raised, lived and died, in Madison County, North Carolina in the heart of Appalachia. They are both buried in Rice Cove, a family cemetery. Their ancestors came from England, perhaps some from Scotland. Folklorist Bascom Lamar Lundsford called Madison County “the last stand of the natural people.” In 1917, ethnomusicologist Cecil Sharp described life in Madison County in his book English Folk Songs from the Southern Appalachians:

The region is from its inaccessibility a very secluded one. There are but few roads – most of them little better than mountain tracks – and practically no railroads. Indeed, so remote and shut off from outside influence were, until quite recently, these sequestered mountain valleys that the inhabitants have for a hundred years or more been completely isolated and cut off from all traffic with the rest of the world.

This article has been snipped and no longer available here. It was enhanced and included in the January-February 2021 issue of Digging History Magazine.

Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Motoring History: Henry Ford (Part Three)

Henry Ford, with only an eighth grade education, always valued hard work. He did, however, make sure that his only child Edsel received a good education at a prestigious Detroit all-boys school. As a young boy, Edsel had followed his father around the plant, much to the delight of Henry – to see his son in coveralls and getting his hands dirty was what he expected.

Henry Ford, with only an eighth grade education, always valued hard work. He did, however, make sure that his only child Edsel received a good education at a prestigious Detroit all-boys school. As a young boy, Edsel had followed his father around the plant, much to the delight of Henry – to see his son in coveralls and getting his hands dirty was what he expected.

All along he was being groomed to run the company someday. However, after Edsel graduated he preferred to spend time with the Detroit well-to-do crowd, marrying into one of the most prominent families in Detroit. Eleanor Clay’s uncle was the founder of the Hudson’s Department Store. The differences in Henry and Edsel were striking – Henry was a highly disciplined individual who neither drank nor smoked and Edsel had a taste for the high life.

All along he was being groomed to run the company someday. However, after Edsel graduated he preferred to spend time with the Detroit well-to-do crowd, marrying into one of the most prominent families in Detroit. Eleanor Clay’s uncle was the founder of the Hudson’s Department Store. The differences in Henry and Edsel were striking – Henry was a highly disciplined individual who neither drank nor smoked and Edsel had a taste for the high life.

This article is no longer available at this site. However, it will be enhanced and published later in a future issue of Digging History Magazine, our new monthly digital publication available by individual purchase or subscription. To see what the magazine is all about you can preview issues at our YouTube Channel. Subscriptions are affordable, safe and easy to purchase and the best deal for getting your “history fix” every month.

This article is no longer available at this site. However, it will be enhanced and published later in a future issue of Digging History Magazine, our new monthly digital publication available by individual purchase or subscription. To see what the magazine is all about you can preview issues at our YouTube Channel. Subscriptions are affordable, safe and easy to purchase and the best deal for getting your “history fix” every month.

I invite you to check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

![]()

Surname Saturday: Rhys and Rice

These two surnames, Rhys and Rice, share similarities. First of all, both are of Welsh origin. Secondly, both can be traced back to the Celts (or Britons) who once lived in the Moor of Wales. Thirdly, both are derived from the old Welsh forename “Ris”, which means “ardour”. Spellings variations for both include: Rice, Rhys, Rees, Reece and others.

Spelling variations of these Welsh surnames might have been due to the challenge of converting them from Welsh to English. The Welsh used the Brythonic Celtic language which contained sounds for which there was no direct translation – the sounds didn’t exist in the English language. In addition, often a family might change their surname, even if slightly, to denote a religious or patriotic affiliation. It seems reasonable to believe that “Rice” is the Anglicized version of “Rhys”.

The Rice surname was brought to Ireland by Welsh settlers and today there are still many Rices in Ireland. Earliest Welsh records mention a person named “Hris” (no surname, however) in 1052. In the Domesday Book of 1086, the result of a survey ordered by William the Conqueror, the surname is listed as “Rees”.

The Rice surname was brought to Ireland by Welsh settlers and today there are still many Rices in Ireland. Earliest Welsh records mention a person named “Hris” (no surname, however) in 1052. In the Domesday Book of 1086, the result of a survey ordered by William the Conqueror, the surname is listed as “Rees”.

The Rhys surname literally meant “the son of Rees.” Records document a person by the name of “William Rys” who lived in County Somerset during Edward III’s reign. Edward Reece, who lived in County Hereford, enrolled at Oxford in 1601. Stories of other notable people with either the “Rice” or “Rhys” surname follow – one a Welsh Baptist minister who immigrated to America in the late eighteenth century, and the other, one of the earliest Rice immigrants to come to America.

Rev. Morgan John Rhys

A quote from Rev. Morgan John Rhys: The Welsh Baptist Hero of Civil and Religious Liberty of the 18th Century:

Dr. Armitage said that Morgan John Rhys was “the Welsh Baptist Hero of Religious Liberty.” Dr. Lewis Edwards, of Bala, Wales, said that he was “a man who had consecrated his life to fight against oppression and tyranny and that he excelled as a defender of civil and religious liberty,” and the Rev. J. Spinther James, M.A., says “that he was a man far in advance of his age, and that he was nor properly known nor properly appreciated by the age in which he lived, nor the one that followed. He was one of the few Welsh who belonged to that class that started the ball of the reformation to roll in Europe. Inasmuch as that ball in its course struck the British government and shattered it, so that the American colonies became free forever, and inasmuch as it also struck the oppressive monarchy of France, so as to cause the great revolution there, so that the English government was so possessed with the fear that the lives of all who advocated liberty were in danger.”

That quote is quite an assignation – to say that someone who lived the majority of his life in Wales was influential in liberating the colonies from British tyranny, as well as plant the seeds of discontent which led to the French Revolution.

Morgan John Rhys was born on December 8, 1760 to parents John and Elizabeth Rees of Graddfa, Llanfabon, Glamorganshire, South Wales. Because his father was a well-to-do farmer, Morgan received the best possible education available at that time. After joining the Baptist Church of Hengoed, he also began to preach. Then it was on to Bristol College in August 1786 to further his education before accepting his first pastorate as an ordained minister at Penygarn Baptist Church. One source called him a “radical evangelical” – his sermons were themed with principles of parliamentary reform and he was also strongly anti-slavery.

He went to France in 1791, believing that the Revolution was an open door to spread the Gospel in that country. He apparently had great success – not long afterwards the Bible was being translated into French. Upon his return to Wales in 1792 he opened a book store and print shop. After speaking at a meeting of churches later that year, he preached in both the Welsh and English languages during the same sermon. In that same meeting, he proposed that money be raised in order to distribute French Bibles.

At the next year’s meeting he urged churches to establish Sunday Schools to teach the young ones how to read the scriptures. With his printing press, he published a book entitled “A Guide and Encouragement to Establish Sunday Schools and Weekly, in the Welsh Language through Wales, with lessons easy to learn, and principles easy for children to understand; and others who are illiteral.”

It was said of Morgan Rhys that when he came up with a good plan he would work to put it into practice quickly. He continued to press the need for Sunday Schools at the 1794 meeting. He also had plans to publish a hymnal. Then something abruptly changed Morgan Rhys’ life.

While meeting with some friends privately at a Carmarthen hotel near the end of July, he was informed that a man had entered the hotel and inquired about his whereabouts. The gentleman hinted that he had been sent from London to arrest Morgan Rhys. When Morgan learned of the plot, he bid his friends a sorrowful goodbye, and on August 1, 1794 he began his journey to America.

When he finally reached New York on October 12, he was met by the pastor of the First Baptist Church of Philadelphia, who was also the Provost of the University of Pennsylvania, the Rev. Dr. Rodgers. The two formed a friendship and almost immediately Morgan returned to the ministry and was met with great success. According to the biography cited above, “He was followed by admiring crowds wherever he spoke, and preached Christ with an earnestness and an unction, but rarely witnessed since the days of Whitfield.”

As he traveled and preached, he was mindful of finding a suitable place to settle and establish his own colony. He married Ann Loxley of Philadelphia and after living there for two years, he and Ann bought a large tract of land which they named Cambria. The seat of the county would be Beulah. In 1798 he removed to Beulah with other Welsh immigrants where he served as both a landlord and pastor of the church in Beulah.

He later left Beulah and moved to Somerset, county seat of Somerset County. Soon afterwards he accepted an appointment as Justice of the Peace for Quemahoning Township, Somerset County, and later as an Associate Judge in the same county. He served in various civil offices until his sudden death on December 7, 1804. Morgan John Rhees (he had changed the spelling of his name after arriving in America) left behind a widow and five children. As death neared he remarked to his wife, “The music, my love, it is so sweet; do you not hear it?” When his wife said she did not hear it, he said, “Oh, listen – now – now – the angels sing come waft on high, we wait to bear thy spirit to the sky.”

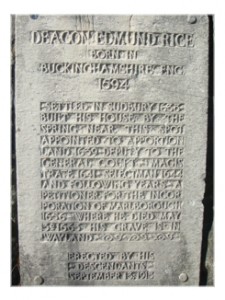

Edmund Rice

Edmund Rice was born in Suffolk, England in approximately 1594. He was a deacon at his local parish, but in 1638 he left England and was one of the early immigrants who joined the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Although it is not recorded why he and his family left, many people who immigrated at that time did so because of religious persecution.

He and his wife and children (seven at least) set out on their journey. Upon arrival with his wife and children, he perhaps first lived in Watertown, Massachusetts. Not long afterwards he helped found the town of Sudbury, and in 1656 he was one of thirteen founders of the town of Marlborough.

After being made a freeman on May 13, 1640, Edmund served Sudbury as a selectman and was ordained as a deacon in 1648. He also became the largest landowner in Sudbury and served in the Massachusetts legislature for five years. Part of his civil duties included laying out roads in Sudbury.

On June 13, 1654, his wife Tamazine (or Thomasine) died. He remarried the following year on March 1 to Mercy Brigham, a widow. When he and other petitioners were granted the right to form the new town of Marlborough, he and his family moved there. Communal farming was practiced in Sudbury, but that practice was apparently not agreeable to Edmund Rice and twelve other dissenters. When Marlborough was established it was specifically organized to be a place where only individual ownership was practiced.

Edmund was elected as selectman in 1657 and every year thereafter until his death on May 3, 1663. Edmund and Thomasine together had ten children: Mary, Henry, Edward, Thomas, Lydia, Matthew, Daniel, Samuel, Joseph and Benjamin. Edmund and his second wife Mercy had two children: Lydia and Ruth.

One of Edmund’s grandsons, Jonas Rice, founded Worcester, Massachusetts. The descendants of Edmund Rice began meeting annually in 1851. Several genealogies have since been published and in 1912 his descendants organized the Edmund Rice (1638) Association (ERA). The following year a marker was erected and dedicated near his home in Sudbury (now Wayland). The Association was incorporated in 1934 and four years later an updated genealogy was published. ERA continued its research and by 1968 26,000 descendants had been verified.

One of Edmund’s grandsons, Jonas Rice, founded Worcester, Massachusetts. The descendants of Edmund Rice began meeting annually in 1851. Several genealogies have since been published and in 1912 his descendants organized the Edmund Rice (1638) Association (ERA). The following year a marker was erected and dedicated near his home in Sudbury (now Wayland). The Association was incorporated in 1934 and four years later an updated genealogy was published. ERA continued its research and by 1968 26,000 descendants had been verified.

In 2013, using a statistical model, it was estimated that the 12th generation alone contained 2.7 million descendants. Generations 1-12 totaled 4.4 million. When allowing for spouses of half that number would bring the total to almost 7 million. When parents of spouses are added in, the astonishing total is near 10 million. No wonder genealogy is such a tedious and time-consuming effort!

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Feudin’ and Fightin’ Friday: Turk-Jones Feud, aka “Slicker War”

This Ozark Mountain feud was carried on much like the more famous Appalachian Hatfield-McCoy feud, encompassing the Missouri counties of Benton and Polk. Benton County was a newly organized county when two families, the Joneses and Turks, migrated from Kentucky and Tennessee, respectively. Colonel Hiram Turk came to Benton County with his wife and four sons: James, Thomas, Nathan and Robert, settling in an area known as Judy’s Gap.

This Ozark Mountain feud was carried on much like the more famous Appalachian Hatfield-McCoy feud, encompassing the Missouri counties of Benton and Polk. Benton County was a newly organized county when two families, the Joneses and Turks, migrated from Kentucky and Tennessee, respectively. Colonel Hiram Turk came to Benton County with his wife and four sons: James, Thomas, Nathan and Robert, settling in an area known as Judy’s Gap.

The Andy Jones family settled along the Pomme de Terre River, a tributary of the Osage River. Jones and his sons had a penchant for gambling, horse racing and were suspected of counterfeiting. They were said to be coarse and likely illiterate as they always signed their names by a mark.

Colonel Turk, as he was called, had served in the Tennessee militia and was said to have been full of buck shot. A businessman in Tennessee, he also opened up a general store and saloon in the recently-designated county seat of Warsaw. Although his family was generally described as being courteous and well-educated, they also had a reputation for being “quarrelsome, violent and overbearing” (A Sketch of the History of Benton County, by James H. Lay).

Colonel Turk, as he was called, had served in the Tennessee militia and was said to have been full of buck shot. A businessman in Tennessee, he also opened up a general store and saloon in the recently-designated county seat of Warsaw. Although his family was generally described as being courteous and well-educated, they also had a reputation for being “quarrelsome, violent and overbearing” (A Sketch of the History of Benton County, by James H. Lay).

Tensions between the two families began on Election Day in 1840 when Andy Jones walked into Hiram’s store, which was being used as a polling place. Jones started an argument with James Turk about a horse race bet. A fight ensued as Hiram and his other sons joined in and his son Tom pulled out a knife. No one was seriously injured but the Turks were charged with inciting a riot and committing assault.

Earlier that year James Turk had attacked a man by the name of John Graham, seemingly unprovoked, near Judy’s Gap. John Graham was a prominent member of the community and on the day following the attack he personally wrote a note to the Justice of the Peace:

February the 19 day – 1840.

mister wisdom sir please to come fourth with to my house and fetch your law books and come as quick as you can as I have been Lay waid by James turk and smartley wounded sow that I Cant Come to your house and is A fraid that he will Escape. JOHN GRAHAM.

When a warrant was issued for James Turk’s arrest a posse arrested him, but Turk refused to go to Graham’s house for the trial – and Graham refused to be in Turk’s presence until he was officially disarmed. Justice Wisdom ordered James to be disarmed and when he stepped in to assist, Hiram intervened and Tom Turk drew his gun on the officers of the court. The Turks and their friends took James home.

A warrant was then issued against the Turks for springing James from custody. Justice Wisdom had James bound over for the assault of John Graham, Tom for rescuing James, and Hiram for the rescue and threatening John Graham. In court, Hiram accused the Justice of malicious prosecution, whereupon the judge fined him twenty dollars. According to James H. Lay, “[T]hese proceedings aided in planting the animosity that took shape in the Slicker war.”

Back to the Election Day brawl. A few days later Tom, James and Robert Turk were indicted for inciting a riot and Hiram and James were indicted for assaulting Andy Jones. In December the three boys were convicted of starting the riot and fined one hundred dollars. Hiram and James’ trial was delayed, however, until the April 1841 term.

The Circuit Court convened on April 3, 1841. Abraham Nowell, a prominent and respected citizen of the community, was the chief witness against the Turks. Nowell was on his way to court with Julius Sutliff, a neighbor of the Turks, when James Turk assaulted him. Abraham Nowell, in self-defense, grabbed Sutliff’s gun and killed James Turk.

Nowell, fearing Turk family retribution, fled the area only to return in September to turn himself into the Sheriff. He was arrested and posted bail awaiting trial in April 1842. Nowell was acquitted, possibly on the strength of testimony against James Turk. One witness, John Prince, testified:

I heard James Turk say that Mr. Nowell was a main witness, and never should give in evidence against them, that he intended to take the d____d old son of a b____h off his horse and whip him, so he could not go to court. Turk further said that if they took the case to Springfield he would have him (Nowell) fixed so he never would get there.

During the spring of 1841 when James was killed, Hiram and Tom had filed a number of “nuisance” lawsuits against their neighbors. After James was killed the tensions between the Turks and Joneses heated up again.

A relative of the Joneses, James Morton, had killed an Alabama sheriff in 1830 and fled to Benton County. On May 20, 1841, a bounty hunter by the name of McReynolds brought indictment papers to the attention of the Benton County sheriff. The sheriff, however, was unconvinced that the evidence was sufficient to warrant Morton’s arrest.

The reward for Morton’s capture was four hundred dollars and McReynolds, determined to bring Morton to justice, recruited the Turks to assist him. The Turks were successful in capturing Morton. After turning him over, McReynolds took Morton back to Alabama where he was acquitted, later returning to Missouri. Meanwhile, Hiram Turk had been charged with kidnapping (charges later dropped).

Of course, this escalated the animosities between the two families. Andy Jones and his family vowed revenge on the Turks. In early July 1841, Jones entered to an agreement with some of his friends to kill Hiram Turk. They went so far as to draw up a binding agreement among all co-conspirators – anyone who divulged the secret plot to kill Hiram would himself be killed.

On July 17 Hiram Turk was ambushed, shot from the brush as he rode through a hollow. Upon being shot, he fell off his horse and exclaimed, “I am a dead man!” Even though he was attended daily by a doctor, he never fully recovered. He lingered for a few weeks and died at his home on August 10, 1841.

Since the Circuit Court was still in session, Andy Jones and several of his friends were indicted for the murder of Hiram Turk. On December 9, 1841, Andy Jones was acquitted, the jury deciding that there was insufficient evidence to convict him. One friend, Jabez Harrison, later confessed that he and Andy, along with three other men were hiding in the brush. He accused Henry Hodges of firing the shot. Some of the co-conspirators, including Hodges, fled the area.

The unsuccessful attempt to convict Andy Jones of Hiram’s murder was when the so-called Slicker War began in earnest (as if these two families hadn’t been seriously feuding for quite some time!). The Turks would not be satisfied until they had exacted their own brand of “frontier justice,” driving the Joneses out of the Ozarks.

So why was it called the “Slicker War”? “Slicking” was a form of punishment common in the Ozarks, perhaps brought by settlers who migrated from Tennessee. Emboldened by the spirit of vigilantism, the Turks took it upon themselves to exact punishment on anyone related to or aligned with the Joneses. Their preferred method was “slicking” – the victim was captured, tied to a tree and whipped with a hickory switch. One way or the other they were determined to get a confession from someone as to who really killed their kin.

Each side formed their own alliances. Just like Andy Jones had made a binding agreement with his friends to kill Hiram Turk, Tom Turk made a similar one with thirty or so of his friends. To make it more palatable, they publicly declared their purpose was to drive out horse thieves, counterfeiters and murders – so who would that be?

The Joneses formed their own alliance known as “Anti-Slickers” for, after all, they had to defend themselves. As it turns out the “Anti-Slickers” were no better than the “Slickers” – they weren’t above using the exact same tactics. In reading the detailed account given in A Sketch of the History of Benton County, one almost needs a score card. The feud even drew members of the community not related to either the Turks or Joneses into the fray. “These slickings threw the whole County into excitement, and the feeling was so intense that the entire community took sides in sentiment with one party or the other, and many good citizens openly favored each side and gave them aid in their law suits.”

By the way, the Turks also got their revenge for Abraham Nowell’s acquittal for killing James Turk. On the morning of October 18, 1842, they shot him dead as he was coming out of his house to fetch some water. Meanwhile, the slickings continued, each side determined to drive the other out of the country.

The feud ended, or at least died down, after the state arrested thirty-eight Slickers for their part in attacking an innocent farmer, Samuel Yates. The case never went to trial. Tom Turk was later killed by one of his own posse members. Andy Jones fled to Texas and Nathan Turk followed him. When Jones was arrested for stealing horses, Nathan’s testimony helped convict him – he was found guilty and hanged.

Nathan Turk would later be killed in a gunfight in Shreveport, Louisiana. Mrs. Turk and her remaining son Robert returned to Kentucky. According to James H. Lay, “She is said to have deeply deplored the violence of her sons and husband. Her share in this bloody drama is unwritten, but it is hard to conceive of a heavier burden of woe than fell to her lot.” Indeed.

The practice of “slicking” was picked up by other would-be vigilante groups. Some residents of Lincoln County, in the eastern part of Missouri, used “slicking” to ostensibly rid their communities of horse thieves and counterfeiters. Unfortunately, several innocent people lost their lives as a result. As the saying goes, “time heals all wounds” – with the passage of time, the practice of “slicking” faded away and ended the Slicker Wars of the Ozarks.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Wild Weather Wednesday: The Great Flood of 1913 (Part One)

The recent disasters of the Titanic sinking on April 15, 1912, the devastating San Francisco earthquake and fire on April 18, 1906, as well as the previous year’s Mississippi River flood which swept through the river valley killing two hundred people and causing $45 million in damages, all paled in comparison to this disaster that took place in the spring of 1913.

The recent disasters of the Titanic sinking on April 15, 1912, the devastating San Francisco earthquake and fire on April 18, 1906, as well as the previous year’s Mississippi River flood which swept through the river valley killing two hundred people and causing $45 million in damages, all paled in comparison to this disaster that took place in the spring of 1913.

The aforementioned disasters were devastating in their own right, but the one that came to be known as “The Great Flood of 1913″ was the most widespread disaster in United States history. Thousands upon thousands of people were affected. The death toll was second only to the Johnstown, Pennsylvania flood of 1889 which killed 2,209 people. In 1913 this super-storm affected communities in Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, Maryland, Michigan, New York, West Virginia, Kentucky, Arkansas, Missouri and Louisiana, and beyond.

This article is no longer available on this web site. It will be re-written and enhanced with footnotes and sources in a future issue of Digging History Magazine. I invite you to check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

This article is no longer available on this web site. It will be re-written and enhanced with footnotes and sources in a future issue of Digging History Magazine. I invite you to check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

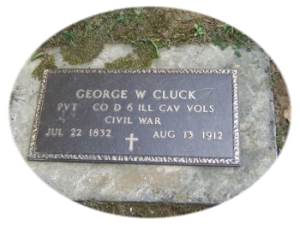

Tombstone Tuesday: George Washington Cluck, Sr.

George Washington Cluck, Sr. was born on July 22, 1832 (or 1833) in Tennessee. His parentage is unclear, although I believe his parents to be John and Mary (Hunt) Cluck. George first appeared in census records in 1850 in Hamilton County, Illinois living with or employed by the Malden family as “Washington Cluck”, aged seventeen.

George Washington Cluck, Sr. was born on July 22, 1832 (or 1833) in Tennessee. His parentage is unclear, although I believe his parents to be John and Mary (Hunt) Cluck. George first appeared in census records in 1850 in Hamilton County, Illinois living with or employed by the Malden family as “Washington Cluck”, aged seventeen.

George married Mary McDaniel, daughter of John and Mary (Hopkins) McDaniel on January 16, 1853 in Hamilton County. Mary was approximately four years older than George, probably born in 1828. These are the children born to their marriage:

Amanda J. – 29 May 1854

William Martin – 06 May 1857

John L. – 01 Oct 1859 (or 1860)

Cassander A. – 16 Apr 1862 – 19 Aug 1862 (4 months, 3 days)

George Washington, Jr. – 02 Feb 1866

Military records indicate that George enlisted as a private on February 7, 1862. Whether he began to serve immediately is unclear. If he was deployed soon after his enlistment, he very likely missed the birth of his daughter Cassander on April 16, 1862 and perhaps never saw her as she passed away at the age of four months and three days on August 19, 1862.

A second enlistment occurred on October 3, 1863 when he joined Company D, 6th Cavalry Regiment Illinois. He was discharged from that regiment and ended his military service on January 28, 1865. Just over a year later his namesake, George Washington Cluck, Jr. was born on February 2, 1866. (One source claimed there was one more child named Delilah who was born after George, Jr., but I could find no record.)

A second enlistment occurred on October 3, 1863 when he joined Company D, 6th Cavalry Regiment Illinois. He was discharged from that regiment and ended his military service on January 28, 1865. Just over a year later his namesake, George Washington Cluck, Jr. was born on February 2, 1866. (One source claimed there was one more child named Delilah who was born after George, Jr., but I could find no record.)

Mary died on October 25, 1872 and was buried in the Knight’s Prairie Cemetery in Hamilton County. She and George had been married for over twenty years and he was left with children who needed a mother.

George married Milinesa Jane “Miley” Braden less than two months after Mary’s death on December 12, 1872, according to family history. Miley was born to parents William and Margaret (Foster) Braden on June 29, 1855, so she was several years younger than George. One interesting note regarding Miley – for the 1860 census Milinesa J. Braden is listed with her other siblings in the Samuel Foster home (possibly her grandparents or some other kin of her mother’s). Milinesa J., William M. and Marinda J. are all listed as five years old – triplets?

The children born to George and Miley’s marriage were:

Milinesa J. – 12 Oct 1874 – 12 Jan 1875 (4 months old)

Clarissa J. – 15 Dec 1875

Dora L. – 04 Feb 1877 – 07 Jul 1900 (23 years old)

Arvice Clarence – 20 Dec 1879

Cora Ada – 25 Jan 1882 – 11 Aug 1901 (19 years old)

Mary J. – 23 Jun 1884

Arthur Lawrence – 23 Jan 1886

Their first child, Milinesa who was named after her mother, was exactly four months old when she died on January 12, 1875. Another daughter, Clarissa was born later that year. Their daughter Dora was only twenty-three years old when she died in 1900 and Cora Ada was just nineteen when she passed away the following year. Some family history sources indicate that Miley had a son from previous marriage or relationship, although I could not locate proof of such.

George lost his second wife when Miley passed away on January 5, 1888, about six months short of her thirty-third birthday. She was buried in the Little Springs Cemetery in Hamilton County.

Again, George was left with young children and he quickly re-married. On April 12, 1888 he married a widow, Cassie Willis Johnson. Cassie was born to parents Eli and Sarah Willis on February 17, 1865. The children born to their marriage were:

Napoleon Bonaparte – 24 Mar 1889

Willard Allen – 05 Aug 1893

Ella Mae – 11 Jul 1894 – 06 Apr 1900

Willis Clarice – 13 Feb 1896

James Elton – 11 Oct 1899

Tragically, shortly after his youngest son James Elton was born, Cassie and Ella Mae contracted a fever (possibly typhoid) in 1900. Cassie died on March 29, 1900 and Ella died a few days later on April 6. They were both buried in Rector Cemetery in Hamilton County. George, now sixty-seven, was once again a widower with several children still living at home.

His fourth wife, Delilah “Lila” Culpepper was born on December 26, 1871, and she and George married on April 7, 1901, according to one family tree. Their only child, born when George was sixty-nine years old, was:

Nellie Rose – 02 Sep 1902

Nellie Rose was the youngest of eighteen children sired by George Washington Cluck, Sr. Some anecdotal family history indicates there may have been one or two additional children but I could find no solid evidence. Interestingly, when Nellie Rose died in 1951 her estate, which was more than $7,000 at the time, was shared with all of George’s children who were still living at the time.

George Washington Cluck, Sr. was a farmer, a soldier, and a father who lived a long and fruitful life. He was said to have been a well-respected member of his community. He had been married for almost sixty years to four different wives, outliving three of them. On August 13, 1912, he passed away and was buried in Knight’s Prairie Cemetery where Mary was buried. Delilah, several years younger than George, lived until November 26, 1949. Delilah was also buried in Knight’s Prairie, as were several of George’s children.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!