Calendar Riots and Time Changes (it’s that time of the year!)

Most of us don’t think about time and its measurement in terms of historical context. It’s just time – something we never seem to have enough of in our “gotta-have-it-now” world. Twice each year our internal time clocks (for the majority of Americans) are re-set because we observe what is called “Daylight Savings Time”. We “lose” an hour of sleep in the Spring, only to “gain” it back in the Fall – “spring forward” and “fall back”. World travelers jet around the world every day, losing a day or gaining one by crossing the International Date Line.

We typically grumble about the loss of zzz’s but our bodies (eventually) adapt fairly well. We certainly aren’t particularly exercised over the loss are we? An hour here, or even a day, is not of much concern. But what if it were eleven days? In the mid-eighteenth century a stir rippled throughout England (although less so in its American colonies) as Parliament enacted calendar reforms in 1751. This calendar-altering event affects genealogical research to this day, yet not as dramatically as it seems to have stirred up the rural populace of England at the time – or perhaps we should say as much as political satirists of the time made of the change and (supposed) uproar.

The January-February issue of Digging History Magazine features an article on this “time change” which will be especially familiar to those of us researching our family history. If you use any type of family tree software it will remind you of this “gap” and ask if you want to make adjustments. Today we have computers to handle those types of “blips” but back then it was a big deal to take eleven days off the calendar. However, whether there were actually riots is debatable. The article, “The So-Called Calendar Riots and Modern Day Genealogical Research” tells the story of how and why the change occurred. As a bonus, the article contains what is inarguably the world’s longest sentence. It’s a direct quote from an eighteenth century newspaper explaining the time change — you have to read it to believe it!

The article wraps up with the story of how Standard Time was set in the United States, which until 1883 was basically non-existent because everyone used what the Chicago Tribune called “fifty-three kinds of time”. Every railroad was on a slightly different time table because there were was no standard time. It’s hard to fathom how trains avoided catastrophic accidents caused by varying time tables.

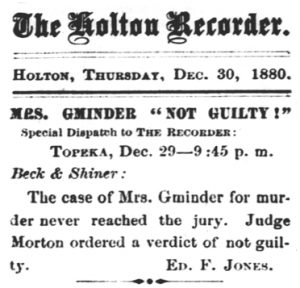

The January-February issue is on sale by single issue purchase or sign up for a subscription (3-month, 6-month or one year) and features extensive articles on the United States census (and more). Not a bunch of statistics, but stories gleaned from census records dating from the first one in 1790 and the last one currently available for public use (1940) — like the woman who became so distressed at having given “incorrect” information to a census taker that she (allegedly) took her own life . . . or, the intriguing story of Annie Gminder, enumerated in a Kansas jail in 1880 (on the “defective schedules” as the suspected murderer of her husband) . . . or the story of some of the toughest census takers you’ll ever read about (and women to boot!).

The January-February issue is on sale by single issue purchase or sign up for a subscription (3-month, 6-month or one year) and features extensive articles on the United States census (and more). Not a bunch of statistics, but stories gleaned from census records dating from the first one in 1790 and the last one currently available for public use (1940) — like the woman who became so distressed at having given “incorrect” information to a census taker that she (allegedly) took her own life . . . or, the intriguing story of Annie Gminder, enumerated in a Kansas jail in 1880 (on the “defective schedules” as the suspected murderer of her husband) . . . or the story of some of the toughest census takers you’ll ever read about (and women to boot!).

This issue is the biggest yet with over 140 pages of articles (and documentation):

- Since It’s a Census Year

- Mining the 1880 Census Mother Lode

- Up in Smoke: 1890 and Genealogy’s “Black Hole” (or is it?)

- What in Blue Blazes . . . happened to my ancestor’s record?

- The So-Called Calendar Riots and Modern Day Genealogical Research

- Getting Knocked Up (A Queer English Custom)

- OK, I Give Up, What is It? Did my ancestors ever violate intercourse(!) laws?

- True Grit: Heck Thomas and Sam Sixkiller

- Family History Tool Box, Book Reviews and more!

Pick up your copy today! The March-April issue will be out by early April (or before), featuring the great state of New Mexico.

Digging History Magazine – January-February 2020

Here we are – the first issue of 2020. “Since It’s the Census” is the theme of this issue which includes stories from United States censuses dating back to 1790 up until 1940, the last census available for public scrutiny (1950 is out in 2022!). You’d be amazed at the stories one can glean from census records (and a fair amount of newspaper research, of course).

I have to say the last several days I’ve felt very much like an overly pregnant woman who is about two weeks overdue. The days seem interminably long as she waits for “that thing to come out” (hence the stork depicting this “somewhat late, yet very special delivery”). I am in fact two weeks overdue from my self-imposed date of January 31 to deliver this issue – and I’m more than ready to “get this thing out”! And, what a big “baby” it is – over 140 pages! The issue is on sale here or purchase a subscription (the best deal) here.

I have to say the last several days I’ve felt very much like an overly pregnant woman who is about two weeks overdue. The days seem interminably long as she waits for “that thing to come out” (hence the stork depicting this “somewhat late, yet very special delivery”). I am in fact two weeks overdue from my self-imposed date of January 31 to deliver this issue – and I’m more than ready to “get this thing out”! And, what a big “baby” it is – over 140 pages! The issue is on sale here or purchase a subscription (the best deal) here.

That being said, I have THOROUGHLY enjoyed researching, writing, editing, etc. this issue – one that I’ve planned to do for quite some time. It just didn’t seem like a better time to do it than the first issue of 2020 as we kick off another census year. As always, I myself have learned TONS and I hope readers will find it informative and entertaining. Please don’t be intimidated by the long articles about the census. I assure you they are FULL of interesting stories.

I was especially amused to have many assumptions I’ve developed over years of genealogical research confirmed – women (and men) fudged their ages, sometimes when an answer couldn’t be provided the enumerator “guessed”. Being a census enumerator was no bed of roses, either, as they struggled to communicate with immigrants suspicious of anything having to do with the government. You’ll especially not want to miss the stories of enumerators who covered their territory on horseback or skis.

This issue of Digging History Magazine is PACKED with stories. Here is a brief summary:

Since It’s a Census Year – What better way to launch 2020 than with an article on this important decennial event. You might be expecting a rather dry recitation of data gathered by the United States government, dating back to the first one conducted in 1790. You would be wrong! I’ve seen the data and accompanying documentation which the government used, and heaven knows only they must understand exactly what it meant!

Census data is vital to genealogical research, yet it’s more than just tick marks (up until the 1850 census), name, age, marital status, occupation and so on. There are literally thousands (more like MILLIONS) of stories to be gleaned – not that I will attempt that feat here, however. This extensive article will look at each decennial census beginning with the first in 1790, through the 1940 census.

Mining the 1880 Census Mother Lode – Family Search refers to the 1880 census as the “mother lode of questions pertaining to physical condition, criminal status, and poverty.” Talk about stories! It took the better part of the 1880s decade to process, but was it ever worth it, all courtesy of the “Supplemental Schedules for Defective, Dependent, and Delinquent Classes” (sometimes referred to simply as the “Defective Schedules”).

Up in Smoke: 1890 and Genealogy’s “Black Hole” (or is it?) – Put on your thinking caps. What event which took place ninety-nine years ago has since become an ever-present challenging obstacle to genealogists? On January 10, 1921 most of the 1890 census went up in smoke – “most” being the operative word. A March 1896 fire had already destroyed a number of these records.

Anyone who has been researching for any length of time likely realizes finding one’s ancestors involves trying many “keys” to unlock hidden caches of records, photos, and so on. Genealogists love census records because they are fairly easy to both access and assess, making the missing 1890 census a discouraging “black hole” for some who haven’t yet tried a little creativity. Why guess (or fudge) when you can do a little extra digging and maybe find a really interesting story! This article is filled with information about this genealogical “black hole” and how to find substitute records utilizing some “research adventure” stories.

The So-Called Calendar Riots and Modern-Day Genealogical Research – Most of us don’t think about time and its measurement in terms of historical context. It’s just time – something we never seem to have enough of in our “gotta-have-it-now” world. Twice each year our internal time clocks (for the majority of Americans) are re-set because we observe what is called “Daylight Savings Time”. We “lose” an hour of sleep in the Spring, only to “gain” it back in the Fall – “spring forward” and “fall back”. World travelers jet around the world every day, losing a day or gaining one by crossing the International Date Line.

We typically grumble about the loss of zzz’s but our bodies (eventually) adapt fairly well. We certainly aren’t particularly exercised over the loss are we? An hour here, or even a day, is not of much concern. But what if it were eleven days? In the mid-eighteenth century a stir rippled throughout England (although less so in its American colonies) as Parliament enacted calendar reforms in 1751. This calendar-altering event affects genealogical research to this day, yet not as dramatically as it seems to have stirred up the rural populace of England at the time – or perhaps we should say as much as political satirists of the time made of the change and (supposed) uproar.

It all seems to involve a bit of revisionist history. In 21st century vernacular let’s call it “fake news”. While researching this article which was to focus on the differences between the Julian and Gregorian calendar systems (sometimes called, respectively, “Old Style” and “New Style”) and how it affects genealogical research, I came across the phrase: “Give us our eleven days!”

Subsequent references to the phrase implied there had been “calendar riots” circa 1752 when England decided to join the rest of continental Europe and adopt the Gregorian calendar which had been around since the 1580s. Attempts to locate the phrase “give us our eleven days” or “give us back our eleven days” in the eighteenth century yielded a big goose egg, although simply using “eleven days” yielded a few references in both England and America around the time of the calendar shift. . . Plus, the story of “setting standard time” in the late nineteenth century (to avoid “fifty-three kinds of time”).

What in the Blue Blazes . . . happened to my ancestor’s (fill-in-the-blank) record? – Family Tree Magazine (May/June 2018) called them “Holes in History” – destructive fires throughout United States history with far-reaching effects on modern-day genealogical research. It might have been the deed to your third great-grandfather’s land in Mississippi, your grandfather’s World War II service record, or the missing 1890 census records. This article will take a look at the stories behind these devastating events and provide tips for finding substitutes.

Here’s something we can all agree on: nineteenth and early twentieth century courthouse fires are the bane of genealogists everywhere. Have you ever wondered why so many courthouse fires occurred in the latter half of the nineteenth century? Would it surprise you to find that many of them were set nefariously? (It shouldn’t.)

Getting Knocked Up (a Queer English Custom) – Once upon a time everyday working folks paid someone to “knock them up”. This, of course, elicits winks and giggles amongst 21st century denizens as “knocked up” often refers to what Merriam-Webster calls “sometimes vulgar: to make pregnant”. There was nothing vulgar intended or implied as this quaint and curious English and Irish custom, begun during the Industrial Revolution and carried forward into the early twentieth century (and beyond for some locales), was an honorable occupation. Before alarm clocks were available and affordable, “getting knocked up” was essential to ensure working men and women avoided fines for arriving late to work.

OK, I Give Up . . . What is It? (Did my ancestors ever violate intercourse(!) laws?) – First, I write an article about getting “knocked up” and now “intercourse laws”. Ahem. Lest anyone think I’m referring to the world’s oldest profession, let me explain. I run across many interesting phrases and curious terms while researching family history for my clients or research for the magazine. One phrase popped up recently and curiosity got the best of me (as it so often does!).

True Grit: Heck Thomas and Sam Sixkiller – This is a companion article to “Did my ancestors ever violate intercourse laws? The short answer — yes, if your ancestor lived near or among Indians they may have at one time or another “violated intercourse laws”. These two legendary “bad-ass” lawmen were kept plenty busy in Indian Territory back in the day.

Family History Tool Box, May I Recommend (Book Reviews) and more!

Sharon Hall, Publisher, Writer, Editor, Graphic Designer of Digging History Magazine

Believe it or not . . . stranger things have happened (Baby Cages and Snowbank Cradles)

Where I live we are “bracing” for a winter storm. People are raiding grocery store shelves like there will be no tomorrow. Trust me, it won’t be as big a deal as everyone is making it out to be (I hope). In honor of the upcoming West Texas “snowmageddon” I thought I’d share a story featured in the February 2018 issue of Digging History Magazine. Enjoy!

This article may very well make you think, “you must be kidding! Seriously?”

To begin with I came upon this story in a rather roundabout way. So, in a roundabout way let me explain. It started with a Christmas sermon about Baby Jesus and how the manger (a feeding trough) served as his crib. The minister explained that in those days there was no such thing as a crib as we know it today. Interestingly, the Old English word “crib” means “manger” or “stall”.

However, it wasn’t until sometime in the nineteenth century when baby cribs came into use. Where did the little one sleep before the 1800s? Though it sounds ill-advised today, children often slept with their mother.

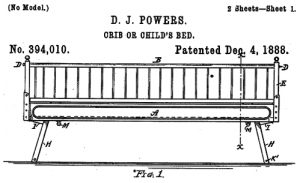

A primary feature of the crib was the ability to keep the child from falling out of bed, necessitating the need for a device which could be easily lowered and raised to place or remove the child. For instance, on December 4, 1888 David J. Powers was awarded U.S. Patent 394010 for a crib or child’s bed. Powers explained:

My improved child’s crib is preferably constructed with a frame having sufficient high sides, upon which the folding panels are hinged to permit the panels to fold down.1

My improved child’s crib is preferably constructed with a frame having sufficient high sides, upon which the folding panels are hinged to permit the panels to fold down.1

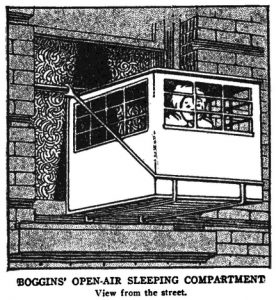

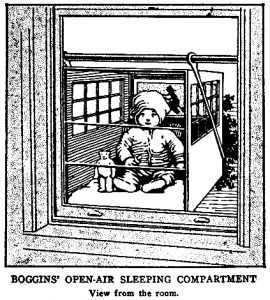

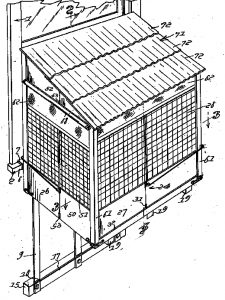

After these types of cribs were invented and improved upon there were other devices, with accompanying theories of proper child-rearing, which began to pop up in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Here’s a depiction of a “baby cage” invented by Emma Read of Spokane, Washington in 1922 and patented (#1448235) the following year.

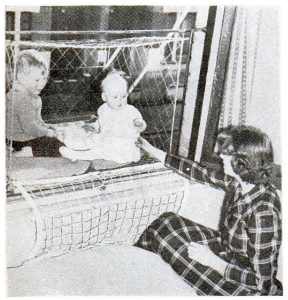

If the image looks a little odd just sort of hanging out there, it’s because it was designed to hang that way – outside a window! These cages began to take off in the 1930s, especially in London (not exactly the healthiest air quality in the world at that time). The July 1953 issue of Popular Mechanics depicted a baby cage accompanied with a description of its purpose:

If the image looks a little odd just sort of hanging out there, it’s because it was designed to hang that way – outside a window! These cages began to take off in the 1930s, especially in London (not exactly the healthiest air quality in the world at that time). The July 1953 issue of Popular Mechanics depicted a baby cage accompanied with a description of its purpose:

Apartment-Window Cage Protects English Tots

Apartment-Window Cage Protects English Tots

Enclosed in a wire cage suspended from an apartment window, English children play in the sunlight and fresh air while their mothers are busy with housework. The cage, made of wire netting, is strongly braced and is guarded on the apartment side by a cloth net which prevents children from crawling back into the room. Loaned by an infant welfare center to families with no gardens, the portable balcony is apparently popular with children and mothers. The demand exceeds the supply.2

The idea of “airing” one’s baby came about in the late nineteenth century as Dr. Luther Emmett Holt explained the concept in his 1894 book, The Care and Feeding of Children. In a chapter entitled “Airing” Holt wrote:

Of what advantage to the child is going out? Fresh air is required to renew and purify the blood, and this is just as necessary for health and growth as proper food.

What are the effects produced in infants by fresh air? The appetite is improved, the digestion is better, the cheeks become red, and all signs of health are seen. . .

What are the objections to an infant’s sleeping out of doors? There are no real objections. It is not true that infants take cold more easily when asleep than awake, while it is almost invariably the case that those who sleep out of doors are stronger children and less prone to take cold than others.3

It would seem the so-called baby cage was in use before Emma Read’s invention in 1922, however. In his book entitled The Health Care of the Baby: A Handbook for Mothers and Nurses, Dr. Louis Fischer, also stressing the importance of fresh air, included illustrations of a device called “Boggins’ Open-Air Sleeping Compartment”, one a view from the street and the other from the inside room.

In 1906 the concept of “airing” one’s baby seems to have taken an extreme turn. In June of that year a women’s club in St. Paul, Minnesota was hosting a clinic on “The Care of Infants and How to Make Child Rearing Easy”. The headline proclaimed:

FROST YOUR BABE, MOTHER’S ADVICE

Clubwomen in St. Paul Told That Chilly Treatment Will Make Their Infants Fat

SNOWBANK BEST CRADLE

Models Shown of “Cage” to Keep Baby In When Mother Attends Meeting of the Club4

Frost your babe? Snowbank best cradle? What was that about!?!

Mrs. Winona S. Abbott was the “expert” and she had been brought to the club meeting by Mrs. Lydia Avery Coonley Ward of Chicago. All ladies present were in St. Paul for a convention of the General Federation of Women’s Clubs, founded in 1890. President Sarah Platt Decker had announced the day before that Mrs. Abbott knew everything there was to know about babies and their care.

There were both married and single women in attendance, clamoring to know more from the “expert”. Some were mother-in-laws with an intense interest in their grandchildren, while some were just struggling with the stresses of raising children.

Mrs. Abbott came well-prepared and stood ready to demonstrate the cadre of “patented appliances for the use of young mothers”.5 She proclaimed a so-called “mechanical baby tender” could mechanically care for the babe whilst its momma attended her club meeting, thus reducing “maternal cares to a minimum and place club life within the reach of all”.6

The newspaper’s description seems to indicate the device was a crib, resembling a cage without a top. Since the mid-1800s several devices deemed “baby tenders” had been patented. Which one she was referring to is unclear, however.

The bars were made of white willow, about two and a half feet high. On one side was a rack for a milk bottle and the other a rack for a rattle. Go ahead and leave little Johnny in the “baby tender” and run off to your club meeting – just make sure he has milk and rattler!

Everything that could possibly keep an infant entertained or provided for was within its grasp. It was noted, however, there was no compartment for “soothing sirup [sic]” – too deleterious, Mrs. Abbott advised.

Her advice included how to dress a squirming baby, serve a five-course meal without getting up from the table, furnish an entire night’s supply of sterilized milk for your baby without making a six trips to the fridge, prevent children from becoming bowlegged or knock-kneed and how to button your infant to its bed to prevent an accidental fall. Whew! What didn’t this woman know about child care?

As one might imagine Mrs. Abbott had “an inviolable set of bylaws for the government of the babe”.7 Her list included, among other things:

● Never use the “indispensable” safety pin. Use buttons instead.

● Always put clothes on a baby by way of the feet – never via the head.

● Never let a baby cry. Crying does not develop the lungs. No baby will cry if treated rightly.

● Give a baby plenty of physical culture. Begin Indian club exercises as soon as possible.

● Never make a baby’s clothes more than twenty-two inches long. 8

As a staunch advocate of the cold air and chilled water treatment for children, she also recommended the child be set outdoors immediately after birth – even if born in the dead of winter. Wrap it in woolen clothes, place in a Klondike bag, hammock or specially-made box and set it outside in the cold to sleep.

Mrs. Abbott claimed her own child had slept outside in -26 degrees, and all the better for it. At 26 months old the child was able to “hold its own weight on a horizontal bar for a minute and a half”.8 At six months old bundle up the babe and plop him or her out in the snow to enjoy the cold weather. You can always warm them up with a nice warm bath, right?

No, actually, according to Mrs. Abbott not nearly so beneficial as a cold one. Again she held up her (apparently) heart and stout children as stellar examples: “my baby won’t get into the bath unless the water is extremely cold”, she explained. “He will sit in cold water for an hour and a half. I would not mind if he sat there three hours. It would do him good.”9

Drafts, however, were a different kettle of fish altogether. Drafts were dangerous! Take the baby out and wrap it so nary a draft strikes it!

Whether this woman was some sort of quack is certainly debatable. She laughed at her critics. One neighbor in the Illinois town where she lived a few years back had reported her to the authorities when she put her baby out in the snow – and now she had the world’s strongest baby! Furthermore, one of her sons had been born paralyzed from the waist down. Currently he was playing football for the University of Illinois, she claimed.

She brought out a prototype of a baby cage and explained the important features necessary to make it effective, claiming it would be a perfectly safe place for the baby to entertain itself – and leaving it there whilst mommy went to her club meeting, one woman piped up! “Exactly!”, exclaimed Mrs. Abbott. That was the point wasn’t it – Mommy need not be inconvenienced in any way in order to pursue her women’s club interest.

What about when the child can scale the two and a half foot “fence”? Mrs. Abbott (she had an answer for every challenge it seemed!) advised, “well, then take a clothes line and tie him to a post. I kept one of my boys tied with a clothes line until he was 6 years old.”10

One of the last devices she displayed was a buffet to be placed next to the bed, although it wasn’t stipulated in the article whether it was mommy’s or baby’s bed. Mrs. Abbott explained how the compartments on either side could hold up to twelve bottles of sterilized milk (a 24-hour supply) – everything needed to make it through the night, plus an upper compartment to hold medicines and a heater over which cereals could be placed. By morning breakfast cereal would be ready!

How much of her advice was taken seriously isn’t clear. Other than her appearance at the women’s club convention there are few (if any) references found for her – except a mocking little poem:

Rest little dear, in the ice chest now, snug as a chop, or a steak, or a roast; Mamma will sing you to sleep, somehow – Wonder which of us will chill the most! Tuck your toes where the chilblains are; Dear little nose – it is nice and blue! Baby must go to the Sleepland afar; Listen and mamma will sing to you. Woo-oo-oo! Br-r-r-r! Woo-oo-oo!11

The baby cage appears to have gained growing interest, however. In 1908 it was suggested in order to keep a baby out of mischief, just saw off the top of a barrel around the first hoop and take out every other stave. Voilà, your own DIY baby cage!

Of course, Emma Read wasn’t the only person to try and design a better baby cage. William Gibbs McAdoo, son-in-law of Woodrow Wilson, constructed an out-the-window cage for his months-old daughter. The son of Wilson’s Republican opponent Charles Hughes, Charles Hughes, Jr., heard about it and decided to give it a try.

Hughes’ children were rolled out in a wagon and placed inside the cage where they would spend their morning nap time. In the afternoon they were taken out to play with their toys. Save for a rainy day the cage worked quite well, although a little cold weather was no problem. Charles Hughes III was said to have become rather husky using this treatment. 12

So, the sermon about Baby Jesus and his manger (crib) led me to write this article – in a roundabout way. The more I read and researched the stranger it became. It’s hard to imagine such practices today – whether throwing your baby out in a snowbank or putting them in a baby cage!

Did you enjoy this article? This is a sample of the kinds of stories you’ll find in each issue of Digging History Magazine. The issue is available by single issue purchase. Subscriptions are the best way to enjoy Digging History Magazine, now published bi-monthly and averaging 75-85 pages (or more!). No ads, just stories of interest to history buffs and genealogists. Want to try a free issue? Pick up one (or two) here: Free Samples.

Deconstruction and Reconstruction: A Necessary Evil for Genealogical Research

Genealogy is not for the faint of heart. I don’t think any serious family history researcher would dispute. How many times have we moved our way up a particular line only to discover either a HUGE brick wall or something which negates all the research we’ve done up to that point? As this post’s title implies sometimes we have to take something apart (or outright destroy!) and put it back together in order to move forward.

Genealogy is not for the faint of heart. I don’t think any serious family history researcher would dispute. How many times have we moved our way up a particular line only to discover either a HUGE brick wall or something which negates all the research we’ve done up to that point? As this post’s title implies sometimes we have to take something apart (or outright destroy!) and put it back together in order to move forward.

Sometimes research for articles works that way too. Since beginning publication of Digging History Magazine in January 2018, I have taken a number of articles previously published at the blog and refreshed them with new research — often re-writing the entire story. Such was the case of the November-December 2019 issue and “The Dash” column. “The Dash” is basically the same premise as the “Tombstone Tuesday” blog articles — “The Dash” referring to a person’s life between birth and death (between the dash).

On April 8, 2014 I published a “Tombstone Tuesday” article about Lycurgus Dinsmore Bigger, someone I came across while researching a story of the family name “Bigger Head” (I have also refreshed this article — details below). This is how I ended the original (2014) 1100-word article:

So, today’s article presented a challenge but still yielded some information about Lycurgus Dinsmore Bigger and his family. Martha’s family genealogy was the most helpful in piecing together their lives and then following up with census, immigration and draft registration records. Still, it isn’t a complete picture, but certainly indicative of the difficulty of historical and ancestry research when one hits a “wall” due to inconsistent, or simply a lack of, reliable information.

Over five years later, here is how I began and ended the 5000+ word article which is included in the November-December 2019 issue of Digging History Magazine:

This article constitutes a major re-write of an early “Tombstone Tuesday” blog article. Back then I didn’t yet have access to the major subscription newspaper archive sites, and I struggled to find details about a man named Lycurgus Dinsmore Bigger and his family. Apparently I didn’t do a very good job of utilizing genealogical records either – boy was I green! This re-write is another great example of how vital newspaper research is to genealogists. . .

I’m fairly sure the 2014 article was chosen because of the unusual name – “Lycurgus Dinsmore Bigger” – that, and I had come across his name while successfully researching and writing an extensive article on a succession of people named “Bigger Head”.

Over five years later it’s evident newspaper research made the difference between an original 1100-word article to a 5000+ word article. I was likely frustrated with the lack of information available at the time, but this so often is the case for genealogists. The old adage “if at first you don’t succeed, try, try again” comes to mind.

Deconstruction (or outright destruction), followed by reconstruction, is a necessary evil for genealogical research. More than merely a “Dash” article this one turned out to be quite an “adventure in research” didn’t it? I hope you enjoyed reading it as much as I enjoyed FINALLY finding the real story of the Bigger family.

I thoroughly enjoyed rewriting the story of the Bigger family and, of course, loved digging around in newspaper archives to discover more about their very interesting lives. Regarding the “Bigger Head” article referenced above, that one was also refreshed and published in the March-April 2019 issue. It is included in an article entitled “Genealogically Speaking: Curious Kin” which features stories of some unusually-named people I’ve run across.

The November-December issue is now on sale and features stories about the War of 1812 — one of those forgotten American wars — and how to find records to help us discover more about our ancestors who served.

Sharon Hall, Publisher and Editor, Digging History Magazine

Family History Charts

This is a chart for someone who was adopted (with natural parentage).

One of my favorite services is creating custom-designed family history charts. It’s a great way to display your family history! I’ve recently added a link on the Services page so that it’s easier to view samples of charts I’ve done for clients. Each one is unique* and, as you can see, sometimes there are blank spaces (and that’s okay!).

Brick walls are inevitable in genealogical research and occur for any number of reasons (no records, flawed research, etc.). A chart can be updated as needed (may involve a small charge) and reprinted. That may sound like an expensive proposition, but it really isn’t. For example, Walgreens Photo offers poster printing up to 36×24 (currently the largest chart produced).. With a 50% off coupon it will cost just $15 (tax excluded) to reprint a chart. Clients receive a copy of the chart on a flash drive and may print as many copies as they like for family members.

Think you can’t afford a chart? When you’re ready to begin, contact me and we can set up a payment plan. Digging History also offers what it calls “Genealogy by Subscription”. For the duration of your project (whether it’s research, family history chart, etc.) you’ll be charged $35 per month, and as a bonus you’ll also receive a Digging History Magazine subscription (published bi-monthly). Chart prices vary according to how many generations will be displayed on the chart. Big or little they are all attractive and conversation pieces (see the Irish Heritage example).

Family history charts also make great gifts — Christmas, anniversary, birthday, family reunions and more! Contact me at [email protected] or give me a call at 806-317-8639.

Sharon Hall

* Charts are as unique as you want them to be and may include pictures, newspaper clippings, cattle brands, signatures and so on. It will be creative!

Digging History Magazine: July-August Issue Features Kansas

The July-August issue of Digging History Magazine features several articles about the great state of Kansas (and it’s the biggest issue yet with 100+ pages, just stories and no ads):

The July-August issue of Digging History Magazine features several articles about the great state of Kansas (and it’s the biggest issue yet with 100+ pages, just stories and no ads):

- “Drought-Locusts-Earthquakes-B-Blizzards (Oh My!)” – Perhaps no state is possessive of a more appropriate motto than Kansas: Ad Astra per Aspera (“To the stars through difficulties”, or more loosely translated “a rough road leads to the stars”1). By the time the state adopted its motto in 1876, fifteen years post-statehood, it had experienced not only a brutal, bloody beginning (“Bloody Kansas”) but had endured (and continued to struggle with) extreme pestilence, preceded by severe drought and even an earthquake in April 1867. In the early days being Kansan was not for the faint of heart.

- “Home Sweet Soddie” – For years The Great Plains had been a vast expanse to be endured on the way to California and Oregon. Now the United States government was making 270 million acres available for settlement – practically free if, after five years, all criteria had been met. The criteria, referred to as “proving up” meant improvements must be made (and proof provided) by cultivating the land and building a home. For many their first home would be a dugout, a sod-covered hole in the ground.

- “Wholesale Murder at Newton” – It’s called “The Gunfight at Hyde Park” or the “Newton Massacre”. One newspaper headlined it as “Wholesale Murder at Newton”, another called it an “affray” and another a “riot”. Whatever, it was bloody, and one of the biggest gunfights in the history of the Wild West, more deadly than the legendary gunfight at the OK Corral.

- “Kansas Ghost Towns” – It might be more appropriate to call this Kansas ghost town, established by Ernest Valeton de Boissière in 1869, a “ghost commune” (Silkville). Nicodemus. There was something genuinely African in the very name. White folks would have called their place by one of the romantic names which stud the map of the United States, Smithville, Centreville, Jonesborough; but these colored people wanted something high-sounding and biblical, and so hit on Nicodemus.

- “The Land of Odds: Kwirky Kansas” – For some of us the mention of Kansas invokes memories of one of the classic films of our childhood, The Wizard of Oz. With a tongue-in-cheek reference this article highlights some of the state’s history and people in a series of vignettes – some serious, some not so serious (the real “oddballs”) in a light-hearted fashion. A rollicking fun article covering a range of Kansas “oddities” and “oddballs”, including one of the most dangerous quacks to have ever practiced medicine, Dr. John R. Brinkley.

- “Mining Kansas Genealogical Gold” – One of my favorite “adventures in research” is to discover obscure genealogical records or perhaps stumble across a set of records at Ancesty.com or Fold3 which turns out to be a gold mine of information. This article highlights some real gems available at Ancestry.

- “Chautauqua: The Poor Man’s Educational Opportunity” – During an era spanning the mid-1870s through the early twentieth century, Kansans, like many Americans across the country, anticipated the summer season known as Chautauqua, an event Theodore Roosevelt called “the most American thing in America”. By 1906 when Roosevelt made such an astute observation the movement had evolved into a non-sectarian gathering, where “all human faiths in God are respected. The brotherhood of man recreating and seeking the truth in the broad sunlight of love, social co-operation.”

- And more, including book reviews and tips for finding elusive genealogical records.

This issue is available by single issue purchase here: July-August 2019 Issue OR by subscription (pay online or by check): Subscribe Online or By Check

Sharon Hall, Publisher and Editor, Digging History Magazine

A Free Offer (with nothing to lose) . . .

You might even gain a few brain cells ! You’ll certainly be able to see what Digging History Magazine is all about with a chance to download a free issue (or two)!

! You’ll certainly be able to see what Digging History Magazine is all about with a chance to download a free issue (or two)!

I’m currently busy putting the finishing touches on the July-August issue which features the great state of Kansas. The issue should be available on or before July 15, featuring articles like: “Drought-Locusts-Earthquake-B-B-lizzard (Oh My!)”, “Wholesale Murder at Newton”, “Kansas Ghost Towns”, “The Land of Odds: Kwirky Kansas”, “Mining Kansas Genealogical Gold”, “Chautauqua: The Poor Man’s Educational Opportunity” and more.

In the meantime I’ve decided to run a limited time offer. Go to the link (https://digging-history.com/free-samples/) and select either (or both) of the free issues being offered (January-February 2019 or March-April 2019). After reading them, I hope you’ll consider becoming a subscriber . . . Enjoy!

Uncovering history one story at a time . . .

Sharon Hall

Researcher, Writer, Graphic Designer, Editor and Publisher

Digging History Magazine

Currently Brewing: Kansas on my Mind

After writing, researching, editing and publishing the current issue (May-June 2019) of Digging History Magazine, swinging back to a bit of ancestry research for clients (and start a family history chart or two), I’m back to “W-R-E-P” mode again. I originally intended the May-June issue to feature articles about two great (neighboring) states: Colorado and Kansas. As it turned out Colorado stories just kept coming (until that issue grew to 100+ pages!), so I decided the next issue would be devoted to Kansas.

After writing, researching, editing and publishing the current issue (May-June 2019) of Digging History Magazine, swinging back to a bit of ancestry research for clients (and start a family history chart or two), I’m back to “W-R-E-P” mode again. I originally intended the May-June issue to feature articles about two great (neighboring) states: Colorado and Kansas. As it turned out Colorado stories just kept coming (until that issue grew to 100+ pages!), so I decided the next issue would be devoted to Kansas.

The current lineup, with more than one tongue-in-cheek homage to Kansas as the “Land of Oz”, includes:

- Drought-Earthquakes-Locusts (Oh My!) – Perhaps no state has a more appropriate motto than Kansas: Ad Astra per Aspera (“To the stars through difficulties”, or more loosely translated “a rough road leads to the stars”). By the time the state adopted its motto in 1876, fifteen years post-statehood, it had experienced not only a brutal, bloody beginning (“Bloody Kansas”) but had endured (and continued to struggle with) extreme pestilence, preceded by severe drought and even an earthquake in April 1867. In the early days being Kansan was not for the faint of heart.

- Home Sweet Soddie – Millions of acres were up for grabs after Abraham Lincoln signed the Homestead Act of 1862 into law. Southerners in Congress had opposed the idea for years, but following secession those obstacles had been temporarily removed. Lincoln truly believed expansion onto public lands with an opportunity to own something would alleviate poverty, while strengthening and growing the country (and benefit the Republican Party). He ran on the idea and signed the legislation into law on May 20, 1862. Weeks later the Pacific Railroad Act was signed into law on July 1. The stage was set for the United States to expand – while fighting to stay together.

For years The Great Plains had been a vast expanse to be endured on the way to California and Oregon. Now the United States government was making 270 million acres available for settlement – practically free if, after five years, all criteria had been met. The criteria, referred to as “proving up” meant improvements must be made (and proof provided) by cultivating the land and building a home. For a “sod buster” selecting a good site was paramount. Much of the Great Plains was near-treeless . . - Kansas Ghost Towns – A look at two or three ghost towns, which in their heyday held special significance in Kansas history.

- The Land of Odds: Kwirky Kansas – A little tongue-in-cheek reference to Kansas and the Wizard of Oz. A look at the famous and the infamous characters and unique events which shaped Kansas history and more.

- Wholesale Murder at Newton – It’s called “The Gunfight at Hyde Park” or the “Newton Massacre”. One newspaper headlined it as “Wholesale Murder at Newton”, another called it an “affray” and another a “riot”. Whatever, it was bloody, and one of the biggest gunfights in the history of the Wild West, more deadly than the legendary gunfight at the OK Corral. In 1871 the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad had extended its line past Abilene, Kansas and established a terminal at Newton. In a pattern repeated numerous times throughout the West during that era – discover gold or silver or put in a railroad line, and towns would quickly go from bucolic to rambunctious. . .

- Mining Kansas Genealogical Gold – A look at some unique records which will help researchers uncover more about their Kansas ancestors, especially those who were European immigrants.

- Ways to (Fashionably) Go in Days of Old: Part 2 – The May-June issue featured an article on some of the “fashionable” ways the fairer sex met their demise in days of old. The article concludes with a look at the gents. Wondering what fashion had to do with someone’s death? Subscribe (the best deal) or purchase by single issue.

- American Self-Portrait: The Federal Writers Project – A look at one part of Franklin Roosevelt’s “New Deal” program known as the Works Progress Administration (WPA) — from travel guides to slave narratives — writers were recruited in an effort to get the country back on its feet and working again during the Great Depression. We’ll explore what these projects were and how to find the records (and use them in your research).

- Chautauqua: The Poor Man’s Educational Opportunity – A look back at a unique piece of Americana which began in the late nineteenth and carried through well into the twentieth century — when summertime meant Chautauqua and a chance for rural Americans to afford themselves of some of the same educational opportunities as city-dwelling citizens enjoyed.

- Research tips, book reviews and more.

These are just a few highlights. Issues tend to expand as I go along — like peeling an onion, uncovering history one story at a time. The issue should be out on or before July 15. Thanks for stopping by — if you’d like to sample an issue of the magazine, subscribe to the blog and a free issue will be on its way to your inbox. Or, if already a blog subscriber, email me ([email protected]) and request a free issue.

Cheers,

Sharon Hall, Publisher and Editor, Digging History Magazine

Test Tube Tots: A 21st Century Moral Dilemma?

Since this is Father’s Day weekend I thought I’d share an article from a recent issue of Digging History Magazine (March-April 2019). In the last few days I’ve noticed other articles along the lines of moral dilemmas regarding DNA tests which are now readily available (and heavily promoted). Yes, it’s fun to find out “who you are” as in what are your ethnic origins, but what if you discover some deep, dark family secret?

This issue has featured a wide range of articles and this one is inspired by the book reviewed on page 23 (Inheritance: A Memoir of Genealogy, Paternity, and Love, by Dani Shapiro). While reading the book I pondered Ms. Shapiro’s story and thought about how others had been unbeknownst-to-them conceived artificially as she was decades ago, and years before established ethical guidelines were in place. My question: does this present a potential 21st century moral (ethical) dilemma?

This issue has featured a wide range of articles and this one is inspired by the book reviewed on page 23 (Inheritance: A Memoir of Genealogy, Paternity, and Love, by Dani Shapiro). While reading the book I pondered Ms. Shapiro’s story and thought about how others had been unbeknownst-to-them conceived artificially as she was decades ago, and years before established ethical guidelines were in place. My question: does this present a potential 21st century moral (ethical) dilemma?

As DNA technology advances at an unprecedented pace I anticipate more stories like hers will come to light. For Shapiro, taking the DNA test was a casual afterthought, yet the results rocked her world – forcing her to adjust to new realities of who she really was in terms of heredity and heritage. Ponderous thoughts . . . and now a little history.

Knocked out, then knocked up (in a colloquial sort of way) is more or less how the first full-term American “test tube tot” was conceived. The year was 1884 when a 31-year-old Quaker woman visited Dr. William Pancoast, a physician at Philadelphia’s Jefferson Medical College. She and her husband wished to have children but as yet had been unable to conceive.

While Pancoast originally assumed the inability to conceive was due to the woman’s infertility, a series of examinations revealed the more likely cause to have been her husband’s low sperm count. Her husband, a wealthy 41-year-old Philadelphia merchant, was healthy – save for a case of gonorrhea years earlier. A two-month course of treatment yielded no change – his sperm remained “absolutely void of spermatozoons”.6

Pancoast made the decision, without informed consent of either the woman or her husband (the moral dilemma part) to proceed with treatment as follows:

In front of six medical students, Pancoast knocked out his patient using chloroform, inseminated her with a rubber syringe, and then packed her cervix with gauze. The source of the semen was one of the medical students in the room, determined to be the most attractive of the bunch.7

Was Pancoast a scientist or some sort of quack, or as one 1965 article suggested, perhaps he submitted to pressure from his students.8 By all accounts William Pancoast was a reputable physician. He was born in Philadelphia in 1835, the son of Joseph Pancoast, a renowned surgeon. After graduating from Haverford College William entered Jefferson Medical College and graduated in 1856. Following extended studies abroad he returned to Philadelphia in 1858, cultivating his own well-regarded reputation as a surgeon.

During the Civil War he served as chief surgeon at a Philadelphia military hospital and in 1862 was appointed Demonstrator of Anatomy at Jefferson. In 1868 he became an adjunct professor and five years later replaced his father as Professor of Anatomy.

Upon retiring from Jefferson, William Pancoast took a new position as a professor at the Philadelphia Medico-Chirurgical College in 1886. His career had been steady, rather uneventful actually, as evidenced by a brief obituary published in The British Medical Journal in 1897:

He contributed largely to the literature of his profession, and his writings were always marked by width and accuracy of knowledge and soundness of judgment.10

It doesn’t sound like William Pancoast was a “roll-the-dice” kind of guy. As a professor of anatomy he perhaps possessed special knowledge about infertility, or perhaps he had read of earlier attempts by J. Marion Sims, founder of New York’s Women’s Hospital. After the hospital’s opening in 1855 Sims attempted fifty-five artificial inseminations on six different women, yet only one procedure resulted in pregnancy before ending in miscarriage.

Pancoast never told the woman the details of her last “examination” before conceiving, and only told the father following the child’s birth. Together, the two men decided it best to keep the circumstances a secret from the mother. Pancoast never wrote of this particular “accomplishment” even though he wrote extensively throughout his career.

The world only became aware of it after one of his students, Addison Davis Hard, present on that day, divulged details of the procedure in an April 1909 letter to the editor of The Medical World. It had been twenty-five years, Dr. Pancoast had died in 1897, and perhaps Dr. Hard decided it was time to unburden his soul. His opening remarks suggest he may have thought for some time regarding the procedure and its ethical implications:

Editor Medical World: – It has been twenty-five years since Professor Pancoast performed the first artificial impregnation of a woman, in the Sansom Street hospital of Jefferson Medical College, in Philadelphia. At that time the procedure was so novel, so peculiar in its human ethics, that the six young men of the senior class who witnest [sic] the operation were pledged to absolute secrecy.13

A.D. Hard described how treatment had progressed to the point where no one had a clue as to how to remedy the husband’s blocked seminal ducts. He continued:

A joking remark by one of the class, “the only solution of this problem is to call in the hired man,” was the probable incentive to the plan of action which followed. The woman was chloroformed, and with a hard rubber syringe some fresh semen from the best-looking member of the class was deposited in the uterus [swearing everyone to secrecy]. . . subsequently the Professor repented of his action, and explained the whole matter to the husband. Strange as it may seem, the man was delighted with the idea, and conspired with the Professor in keeping from the lady the actual way by which her impregnation was brought about. In due course of time the lady gave birth to a son, and he had characteristic features, not of the senior student, but of the willing but impossible father.14

Dr. Hard had recently met the boy who was by then a New York City businessman. His article took on a bolder tone after suggesting a society for propagating the practice of artificial insemination was in order. It sounded very much like eugenics which, at the time, was “all the rage”. Interestingly, the term “eugenics” had been coined in 1883, one year before Pancoast’s experimental procedure, by Francis Galton, a cousin to Charles Darwin. The word, derived from Greek, means “good in birth” or “noble in heredity.”15

Hard went on to expound regarding artificial impregnation, marriage and venereal disease:

Marriage is a proposition which is not submitted to good judgment or even common sense, as a rule . . . Artificial impregnation by carefully selected seed, alone will solve the problem. It may at first shock the delicate sensibilities of the sentimental who consider that the source of the seed indicates the true father, but when the scientific fact becomes known that the origin of the spermatozoa which generates the ovum is of no more importance than the personality of the finger which pulls the trigger of gun, then objections will lose their forcefulness, and artificial impregnation become recognized as a race-uplifting procedure.16

“Race-uplifting procedure” was no doubt a phrase lifted from the ethos of that era amidst growing interest in the “science” of eugenics. The more he wrote, the more he sounded like a hard-core eugenicist:

It is gradually becoming well establisht [sic] that the mother is the complete builder of the child. It is her blood that gives it material for its body, and her nerve energy which is divided to supply its vital force. It is her mental ideals which go to influence, to some extent at least, the features, the tendencies, and the mental caliber of the child. . . It is the predominating mental ideals prevailing with the mother that shapes the destiny of the child. . .

A scientific study of sex selection without regard to marriage conditions, might result in giving some men children of wonderful mental endowments, in place of half-witted, evil-inclined, disease-disposed offspring which they are ashamed to call their own…

The man who may think this idea shocking, probably has millions of gonnococci swarming in his seminal ducts, and probably is wife has had a laparotomy which nearly cost her life itself, as a result of his infecting her with the crop reaped from his last planting of “wild oats.” . . .

Go ask the blind children whose eyes were saturated with gonorrheal pus as they struggle thru the birth canal to emerge into this world of darkness to endure a living death; ask them what is the most shocking thing in this whole world. . . They will tell you it is the idea that man, wonderful man, is infecting 80 percent of all womankind with the satanic germs collected by him as his youthful steps wandered in the “bad lands.”17

A.D. Hard had unburdened his soul (rather ickily), “outed” Dr. Pancoast, sounded much like a male feminist, even more so a eugenicist (or so it seemed). However, in a July 1909 article published in the same journal, he brushed aside the original article’s bold assertions, implying “it had been embellished with radical personal assertions calculated to set men thinking.”18

He did in fact “set men thinking” as the next few issues published varying thoughts:

I greatly enjoyed his article and have given the idea much thought. I have personally used the impregnator with success o mares that were apparently steril [sic], and have read what I could find on the procedure in the human family. If, from a commercial standpoint, it be a paying process in the animal kingdom, why would not its influence be many times greater in the human family? Male colts that are not promising individuals are promptly castrated, and yet they are not diseased, and in this way the quality of horse flesh is looking forward; but we are standing idly by and witnessing thousands of infected young men of fine families select a pure, innocent young girl, perhaps your own, to deposit the deadly seed of his “prodigal” reaping, resulting in the train of symptoms in women so common to the surgeon today . . . Why not adopt the castration plan in the human family and save the state and Nation the responsibility of having the charge in the state institutions of these deaf, blind, insane, and criminals?19

Yikes! J. Morse Griffin of Sulfur Springs, Arkansas certainly didn’t mince words did he?

A doctor, writing to the editor in the same issue cited above, mistook Hard’s “hard-line” assertions, unable to believe the story of Dr. Pancoast was true at all:

Some notice, I think, should be taken of Dr. Hard’s dream (page 163). I wondered what he had eaten for supper, or what is his brand of drinking water. Dr. Pancoast was a gentleman, and would not countenance the raping of a patient under an anesthetic. . . The story of taking the gentleman’s seminal fluid to be examined by the students to see it it contained any “spermatozoons” is a flight of fancy worthy of Munchausen.20

Others opined:

“ridiculously criminal” (N.J. Hamilton, M.D., Buswell, Wisconsin);

“a ridiculous jumble of fact . . . I must admit that I do think this article shocking, not only to me but to any male or female who has a proper understanding of marital relations or the laws of God. . . Furthermore, I have as healthy and bright a child as one could wish for, and she was not begotten with a hard rubber syringe, either.” (C.L. Egbert, Glenville, Nebraska)21

Dr. Hard had to ‘fess up in the July issue, however, in answer to his many critics:

I cannot convey to you an idea of the amount of pleasure that the varied answers to my article on “Artificial Impregnation” have given me. In answer to all my critics and reviewers, I wish to say that while the article was based upon true facts, it was embellisht [sic] purposely with radical personal assertions calculated to set men to thinking on the subject of generativ [sic] influences and generativ [sic] evils. Bless my critics. I would not wish to own a child that was bred with a hard-rubber syringe. And I do not care to think that my child bears toward the millenium no traces of his father’s personality, humble tho it be. I am a firm disciple of impregnation in the good old orthodox manner, with all its esthetic features and risks of evil. Let us now pull the trigger of some other gun, and set free another explosion of cerebral action.22

Engendering “explosions of cerebral action” notwithstanding, the journal’s editor was not, it appears, amused by Hard’s repartee, adding “[And the editorial department will hereafter realize that you are not to be taken seriously, and act accordingly.–Ed.]”.

Dr. Hard, all kidding aside, had set off a firestorm of opinion, both for and against the practice of artificial impregnation – at least in regards to the human variety.

Actually, the term “artificial impregnation” had been around for quite some time. In terms of the proverbial “birds and bees” these references had been on the “bees” side, focused on creating hybrid seeds, various plants and flowers. By the late 1870s the subject of “artificial impregnation” of fish was openly discussed in newspapers.

When the original story was published in 1909, the world was still processing its exit from the prudish Victorian Era. Openly speaking of plants and fish in terms of artificial impregnation was one thing, the human variety quite another. Still, by the mid-twentieth century technology advanced and artificial insemination had taken place, just not openly. Dr. Edmond Farris, of the Institute for Parenthood on the campus of The University of Pennsylvania (Penn) in Philadelphia, was operating (more or less) in a “legal no-man’s-land.”23

Farris, aware of widespread and historical religious thinking, nevertheless believed he was acting ethically:

I see nothing wrong in trying to bring children of fine quality into the world. We’re not in this for monetary gain.

We select a donor who matches the father in everything but blood. Color of hair and eye is the same. We even consider build and religion.

He described the donors in his institute as the “best material that Philadelphia medical schools can offer.”24

The practice of artificial insemination was an “open secret”, with little or no regulation through the 1970s, as Dr. Michael Glassner remembers from his medical school days: “The ob-gyn walks down the hall and says: ‘How tall are you? Are you healthy? How’d you like to make $100? Here’s a cup.’”25

In 1958 Dr. Farris saw nothing wrong with bringing “children of fine quality” into the world via artificial insemination. The practice, colloquially known as “test-tube baby” was, however, making headlines around the world – in many cases not in a good way, either. The public was already questioning such things as “test-tube baby” legal rights:

Q. Do “test tube” babies have the same legal rights as other children?

A. If the husband is the father there seems to be no special legal problems. When the husband is not the father, things get pretty involved. Laws always lag behind scientific discoveries. When our laws were made no on had any idea that “test tube” babies were possible. Lawyers will have to start from scratch and determine what legal right such children have.26

In Edinburgh, Scotland a judge has just ruled that a wife who had given birth to a test tube baby after separating from her husband was not in fact committing adultery. Indeed, her defense counsel had admitted the case was “unique in the annals of our law.”27

Ronald G. MacLennan of Glasgow was suing wife Margaret (who had since removed to Brooklyn, New York) for divorce on the grounds of adultery. The two had separated in March of 1954 and the following year on July 10 she gave birth to a girl. Without her husband’s consent or knowledge she had been artificially inseminated.

The ruling, in turn, set off a firestorm across Great Britain, despite “the traditional British reluctance to discuss sex in public.” The Archbishop of Canterbury vehemently denounced the practice as evil, demanding artificial insemination by anonymous donor (AID) be made a criminal offense!28

Was it “Blessing or Sin” as one British medical expert had gone on television to discuss? At the time of his interview, Dr. Alfred Byrne revealed there were already 1,000 to 1,500 so-called test-tube babies in Britain. Statistically speaking, Byrne revealed one in every eight marriages were unlikely to conceive without artificial means. In his opinion, however, the trouble (9 out of 10 times) lay with the woman.

One panel member, a lawyer, was of the opinion that AID rendered the child illegitimate. Public opinion was mixed in response to the television program:

● I am the mother of a test-tube baby. He is now five, and his coming, with my husband’s full knowledge and consent, made all the difference to our marriage. I say to the Archbishop of Canterbury: ‘If it is wrong to be happy, then we have done wrong’.

● A child conceived in this revolting way is a sin against all laws of nature. If, however, this method is right, it is not wrong for a child to be born out of wedlock.

● However evil artificial insemination may be, its result is to create children, rather than destroy them.29

And, for hundreds of families, the desire for children and the ability to produce them – whether naturally or artificially conceived – was the most salient point of all.

Following the uproar surrounding the Scottish case, reports of test tube babies, parental rights, as well as opinions both pro and con, erupted in newspapers. Test-tube baby court trials, often involving divorce proceedings, made for riveting headlines. Much like A.D. Hard’s provocative 1909 article, it “set men (and women) to think.”

An “ordinary” Australian housewife couldn’t understand (as the mother of four, trying to raise them with Christian training) “the medieval attitude of those who oppose artificial insemination on moral grounds.”30 Yes, clerics could argue if a woman was barren then it was surely God’s will. Then, again, God had also given man the knowledge and abilities to produce miracle-working medical procedures. Surely it was the right of every married woman, her primary right, to produce a child. If it was legal to place a child with a couple who weren’t its biological parents, then why was it wrong to conceive them artificially.

This ordinary Australian housewife had a point. Technology to help childless couples produce offspring was rapidly advancing, although one wonders how much thought (if any) these couples put into potentially ethically-challenging consequences decades into the future.

Modern DNA research rapidly advanced after Oswald Avery identified genes as discrete units of heredity in 1944. In 1959 Down’s syndrome was officially linked to the presence of an extra chromosome (21). Yet, DNA sequencing and mapping technology were still decades away in the 1950s.

Dani Shapiro was artificially conceived via AID in the early 1960s, her mother desperate to have a child of her own. As a child growing up with Jewish parents she would sneak down the hallway to the bathroom after her parents were asleep and stare into the mirror, searching for features which bore similarity to her parents.

Fast forward fifty-plus years and casually take a DNA test. Shapiro was at first merely confused by her results which showed only 52 percent Ashkenazi Jewish (Eastern European) ancestry. As far as she knew her parents were Jewish through-and-through. The rest of her DNA makeup was French, Irish, English and German.

Startlement set in, however, after discovering the person she always assumed to be a half-sister (her father’s daughter from a previous marriage) was not related biologically. DNA technology now makes it possible to pinpoint not only ancestral ethnicity, but the ability to link us to biological kin we never knew we had. That same technology also makes it possible to “un-link” them. A five-minute “spit test” can change a person’s perception of biological parentage – just like that.

If this had happened to me, how would I have responded? If it happened to you, would it turn your world upside down?

Ponderous thoughts, indeed.

The March-April 2019 issue featured several other articles which are summarized in this blog post. The issue is available by single issue purchase. Subscriptions are the best way to enjoy Digging History Magazine, now published bi-monthly and averaging 75-85 pages (the current issue is 100+ pages). No ads, just stories of interest to history buffs and genealogists. Want to try a free issue? If you’re not a subscriber to this blog, sign up today and receive a free issue to see what Digging History Magazine is all about. Already a blog subscriber and haven’t yet received a free issue? Email me: [email protected]. (You can even choose the issue you’d like to preview [current issue excluded] by perusing the list of magazine archives.)

The March-April 2019 issue featured several other articles which are summarized in this blog post. The issue is available by single issue purchase. Subscriptions are the best way to enjoy Digging History Magazine, now published bi-monthly and averaging 75-85 pages (the current issue is 100+ pages). No ads, just stories of interest to history buffs and genealogists. Want to try a free issue? If you’re not a subscriber to this blog, sign up today and receive a free issue to see what Digging History Magazine is all about. Already a blog subscriber and haven’t yet received a free issue? Email me: [email protected]. (You can even choose the issue you’d like to preview [current issue excluded] by perusing the list of magazine archives.)

Hope you enjoyed the article! To all the fathers out there — Happy Father’s Day!

Sharon Hall, Publisher and Editor, Digging History Magazine