Ghost Town Wednesday: Cloverdale, New Mexico

Cloverdale is believed to have been established sometime in the 1880’s. On May 2, 1882 The Critic (Washington, D.C.) had a story about an Indian fight at Cloverdale between Apaches and the Sixth Cavalry, led by Captain T.C. Tupper. One soldier was killed in the battle, two wounded and fourteen Apaches were killed. It was not the first battle with Indians in the area and certainly not the last – the war with Apaches continued until about 1924.

Cloverdale is believed to have been established sometime in the 1880’s. On May 2, 1882 The Critic (Washington, D.C.) had a story about an Indian fight at Cloverdale between Apaches and the Sixth Cavalry, led by Captain T.C. Tupper. One soldier was killed in the battle, two wounded and fourteen Apaches were killed. It was not the first battle with Indians in the area and certainly not the last – the war with Apaches continued until about 1924.

This article has been updated and published in the September-October 2021 issue of Digging History Magazine, included in an article entitled “Tales From the Bootheel and Beyond: The Ghost Towns and Storied History of Southwestern New Mexico”. You may purchase the issue in the magazine store: September-October 2021 Issue.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues and a selection of sample articles here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Tombstone Tuesday: Tales From Cloverdale Cemetery (Cloverdale, NM)

I just never know where a story idea will pop up. This one came from some bantering back and forth on Facebook between my brother and one of our cousins about the “Bootheel” area of New Mexico. Today’s article features one family who started out in Texas, wandered up and down the Pecos Valley of New Mexico for years, and finally ended up in Hidalgo County at a volatile time in history.

I just never know where a story idea will pop up. This one came from some bantering back and forth on Facebook between my brother and one of our cousins about the “Bootheel” area of New Mexico. Today’s article features one family who started out in Texas, wandered up and down the Pecos Valley of New Mexico for years, and finally ended up in Hidalgo County at a volatile time in history.

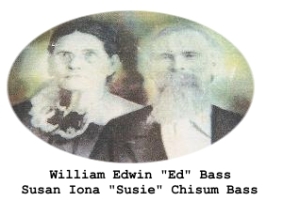

The Bass Family

The patriarch of the Bass family, William Edwin “Ed” Bass, was born in July of 1854 to parents Richard and Sarah Francis (Means) Bass in San Patricio County, Texas. In 1872 he married Susan Iona Chisum in San Patricio County. Together they raised a large family of twelve children:

Richard Isom (1873)

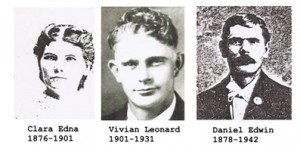

Clara Edna (1876)

Daniel Edwin (1878)

William Holland (1880)

Susan Iona (1882)

Margaret (1885)

Ludie Mary (1888)

Eva May (1890)

Frederic (1894)

Clyde (1895)

Edgar (1898)

Vivian Leonard (1901)

Note: Susie’s obituary noted that she raised fourteen children. However, available census records indicate only twelve.

Ed and Susie resided in Bandera County, Texas in 1880 with four young children. Sometime after the 1880 census, the family moved to the Pecos Valley of New Mexico. They settled in an area called Hackberry Draw, then moved back to the plains and later returned to the valley on land near the Black River. Ed and his neighbors built a school house there which was also used as a community gathering place.

Ed and Susie resided in Bandera County, Texas in 1880 with four young children. Sometime after the 1880 census, the family moved to the Pecos Valley of New Mexico. They settled in an area called Hackberry Draw, then moved back to the plains and later returned to the valley on land near the Black River. Ed and his neighbors built a school house there which was also used as a community gathering place.

The Bass family were wanderers apparently and later moved to Eddy (now Carlsbad), where Ed owned and operated a livery stable, ranched in Artesia and finally sold out and moved to Cloverdale, Hidalgo County in 1917. The family picked an historic time to live in the Bootheel of New Mexico when they settled in an area near the Mexican border (their home was within a half-mile of the border).

The Mexican Revolution had begun in 1910 and continued until at least 1920. One of the most well-known Mexicans in the area would have been Francisco “Pancho” Villa. Indian raids were not uncommon (occasionally) either, all of which meant that everyone was armed and on guard. Susie was known for her generosity and kindness, according to her obituary:

If Mother Bass ever had to defend herself from the rougher element of the Old West, no one ever heard of it. She lived a life of unselfishness and generosity, and was loved by the bad as well as the good. The worst “hombre” would have defended her, for the night was never too dark or cold for her to leave her bed and prepare a meal for a hungry traveler, or go see some sick woman or child among her neighbors.

Their sons raised sheep in Hidalgo County and Ed remained in Cloverdale until his death on March 9, 1925. His obituary included the following description: “Ed Bass had a heart of gold and a cursing vocabulary that would reach from hell to breakfast.” His tombstone is inscribed with the words “Life’s work all done, he rests in peace.”

Their sons raised sheep in Hidalgo County and Ed remained in Cloverdale until his death on March 9, 1925. His obituary included the following description: “Ed Bass had a heart of gold and a cursing vocabulary that would reach from hell to breakfast.” His tombstone is inscribed with the words “Life’s work all done, he rests in peace.”

Susie returned to Eddy County and lived there until her death on March 27, 1950. In her obituary, she was remembered as “one of New Mexico’s best-known and loved pioneer women of the Old West” and an adherent of the Baptist faith for seventy-eight years. She died at the age of ninety-two, having entered the hospital a week earlier for the first time in her long life.

Two of their children, although adults, had died young. Their son Vivian Leonard, born in 1901, was just a few weeks short of his thirty-second birthday when he was thrown from his horse while riding the range just east of the Arizona border. He was killed instantly when his head struck a rock (December 11, 1931). Their oldest daughter, Clara Edna, had married Len Scott in Eddy County in 1898. At the time of her death in 1901, she was pregnant with their first child. She died of smallpox.

Two of their children, although adults, had died young. Their son Vivian Leonard, born in 1901, was just a few weeks short of his thirty-second birthday when he was thrown from his horse while riding the range just east of the Arizona border. He was killed instantly when his head struck a rock (December 11, 1931). Their oldest daughter, Clara Edna, had married Len Scott in Eddy County in 1898. At the time of her death in 1901, she was pregnant with their first child. She died of smallpox.

Another son, Daniel Edwin, met an untimely death in 1942 at the age of 64 when he was murdered in Fort Huachuca, Arizona. He ran a bowling alley and was attacked with a bowling pin, crushing his head. His body was interred in Cloverdale Cemetery with his parents and Vivian.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Surname Saturday: Overhuls (Oberholzer)

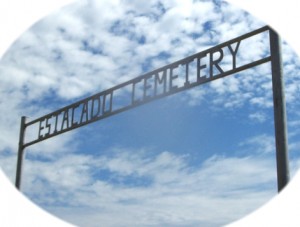

Who knew that a visit to a prairie cemetery in West Texas could generate so many articles (and I’m not done yet!)? Today’s Surname Saturday article focuses on another name found in the historic Estacado Cemetery. Other articles related to this cemetery can be found here, here and here.

James Edward and Emeline Jane (White) Overhuls are buried in the cemetery. As noted on his gravestone, James was a Civil War veteran who served in the 6th Kansas Cavalry. Emma must have been a special lady of fierce determination, as noted on her tombstone: “This marker is also dedicated to the strong-willed women who helped settle the western frontier.” The children born to their union were:

Josephine M. (12 Dec 1866)

George H. (14 Dec 1867)

Cornelius E. (14 Mar 1869)

Mary Ethel (25 Mar 1871)

Octavia (6 Dec 1873)

Emma (6 Dec 1875)

All of their children, except Emma, lived to adulthood; Emeline died in 1876. According to family history, James did not remarry until 1888 so for several years he was a single parent. He and May Jones Lewis had three children of their own:

Fannie M.

Marguerite

Ida Louise

James was a farmer and rancher and died on July 17, 1895.

So where does the surname Overhuls derive from? It is likely that the name derives from the surname Oberholzer which, according to House of Names was first found in Austria:

. . . where the name Oberhofen and Udelhofen were synonymous with the Teutonic Order. The Barons Oberhofen became noted for its branches in the region, each house acquiring a status and influence which was envied by the princes of the region. In their later history the name became a power unto themselves and were elevated to the ranks of nobility as they grew into this most influential family.

Other branches of the Oberholzer family originated from the Swiss region of Oberholz and over time the surname evolved to include variations such as: Oberholtz, Uberholtzer, Overhuls, Overhalt, Overhults, Oberheuser, Oberhofen, Udelhofen and more.

Another source indicates that the Oberholzer surname was derived from “Ober”, a German word which might have referred to someone living at the upper end of a village or perhaps someone who lived on the upper floor of a building. Other possible variations of the surname would also include: Obermann, Overmann, Oberth, Avermann and more.

When the Oberholzer name began to evolve is unclear, although 4Crests.com reports that many Germans anglicized their names after immigrating to America, often by dropping a single letter.

One of the earliest recorded Oberholzer immigrants was Jakob Oberholzer who arrived in 1731. The record included immigrants from Alsace-Lorraine (France), Switzerland and southern Germany. Another immigration record referred to “Swiss Mennonite Family Names”.

One of the earliest recorded Oberholzer immigrants was Jakob Oberholzer who arrived in 1731. The record included immigrants from Alsace-Lorraine (France), Switzerland and southern Germany. Another immigration record referred to “Swiss Mennonite Family Names”.

For James Overhuls’ family the name may have changed during his generation. One family tree indicates that his father was born Cornelius Overholser, but the children are all listed as “Overhuls”. It appears that Cornelius’ family had migrated from Pennsylvania to Darke County, Ohio in the early 1800’s, but no one seems to know much about his parentage. If the spelling which Cornelius’ family used was “Overholser” then it seems quite plausible that “Overhuls” would be derived from the Swiss (or German) surname of Oberholzer.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Feudin’ and Fightin’ Friday: A Bloody One in Arkansas

The Arkansas feud known as the Tutt-Everett War or the King-Tutt-Everett War or the Marion County War wasn’t over love, money, water or land – it was pure politics and it was bloody. The Marion County War might be the most appropriate name since it eventually seemed to have involved just about every citizen in the county.

The Arkansas feud known as the Tutt-Everett War or the King-Tutt-Everett War or the Marion County War wasn’t over love, money, water or land – it was pure politics and it was bloody. The Marion County War might be the most appropriate name since it eventually seemed to have involved just about every citizen in the county.

The Tutt family, led by Hansford “Hamp” Tutt, had come to Searcy County, Arkansas from Tennessee sometime in the 1830’s. The Tutts were members of the Whig Party and wielded political influence in Searcy County. They were also known to be a rough bunch – gambling, horse racing, fighting and drinking. Hamp was a merchant and also owned a saloon which served as a local hangout.

The Everett family of John, “Sim”, Jesse and Bart were members of the Democratic Party and wielded great influence in the area where they lived. Marion County was created in 1836 by the Arkansas legislature out of the area where the Everett family resided. It would also place the Tutts in the same county as the Everetts. To add a little more drama, the King family, fellow Whigs, joined up with the Tutts.

The Everett family of John, “Sim”, Jesse and Bart were members of the Democratic Party and wielded great influence in the area where they lived. Marion County was created in 1836 by the Arkansas legislature out of the area where the Everett family resided. It would also place the Tutts in the same county as the Everetts. To add a little more drama, the King family, fellow Whigs, joined up with the Tutts.

By 1844 most of the county’s three hundred or so residents had lined up behind one faction or the other. The first noted public confrontation between the two sides occurred in Yellville in June of 1844 at the site of a political debate. A brawl, which would later be seen as the match that “lit the feud”, broke out – no guns, just fists, rocks and whatever else they could grab.

In the middle of the fray one of the Tutt supporters, Alfred Burnes, struck Sim Everett in the head with the blade of a hoe, cutting a large gash. Burnes, thinking he’d killed a man, quickly fled the scene. Sim did recover but thereafter both sides never ventured out unarmed. A series of lawsuits and brawls in the ensuing years served only to continue fanning the flames.

As volatile as the situation was, the first gunfight didn’t occur until October 9, 1848 in Yellville. When the gun smoke cleared, several men lay dead, including Jim Everett. Retaliation was swift when two days later the remaining Everetts ambushed and killed Billy, Sr. and Loomis King. Billy’s son and a friend of the family were both wounded but managed to escape.

For the next several months, gun fights continued to erupt although there were no more fatalities. Tensions increased when Ewell Everett became an elected judge, while George Adams, a supporter of the Tutts, was elected constable. The Everett support waned a bit though by the end of the year when Jesse Everett and ally Jacob Stratton decided to move on to Texas.

By the summer of 1849 Sheriff Jesse Mooney, having a reputation as a tough and principled lawman, decided to organize a posse and end the feud. The posse was organized on July 4 and subsequently the biggest gun fight of the entire feud also occurred on that day. Before the posse was fully engaged, the Everetts already had a plan to ambush the Tutts who had assembled at the saloon.

The gun fight was a fierce one, and when the ammunition was spent the fighting continued with rocks, sticks, bricks, again whatever they could lay their hands on. This time the body count was much higher – ten men, including one King (Jack), two Everetts (Bart and Sim), and three Tutts (Davis, Ben and Lunsford) lay dead. Dave Sinclair, an ally of the Tutts who presumably killed Sim, was killed by Everett allies the following day.

When Jesse Everett learned of the deaths of his family members, he returned to Arkansas to avenge their killings, unsuccessfully attempting to kill Hamp Tutt several times. Stepping in again, Sheriff Mooney sent his son Thomas to the capitol to ask the governor to intervene and send the state militia. The governor agreed to intervene but Thomas never made it home, presumably ambushed by one of the factions or the other. His body was never found, although the carcass of his horse later washed up in a creek.

On August 31, 1849 three King family members were ambushed by the Everetts. In September a militia was raised in neighboring Carroll County and later relieved Mooney of his duties. Several members of the Everett faction were arrested, but following the militia’s retreat were freed after a jail break. So much for martial law.

In September of 1850 the feud was essentially over when Hamp Tutt was killed, some believe by a mysterious man from Texas hired by the Everetts. It would become known as the most famous and bloody feud in Arkansas history.

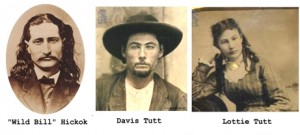

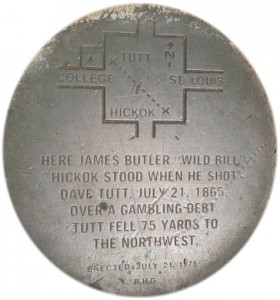

Interestingly, Davis Tutt, only a child at the height of the Tutt-Everett feud, made history of his own on July 21, 1865. Said to have been the date of the first Western gunfight, James B. “Wild Bill” Hickok killed him over a gambling debt on the town square in Springfield, Missouri. The event is commemorated at the spot where Hickok stood with an historic marker:

Davis’ sister, was Wild Bill’s girlfriend.

Davis’ sister, was Wild Bill’s girlfriend.

Story update from reader C C Hoop: I am related to Hansford Tutt. He was my 4th Great Grandfather. Davis Tutt was my 3rd Great Uncle. He did not have a sister named Lottie. His sisters were Susan, Rachel, Sara, Dulcenia and Josephine. We have heard several different scenarios where Wild Bill supposedly had an affair with one of Davis’ sisters. Some scenarios say it was Dulcenia but she died in 1863. Josephine, however, had two children out of wedlock. They were to have been the children of a man named Lindville. Josephine later married a man by the name of Dr. Simms. She and her husband took her youngest son and they moved out of Marion County. The oldest son, Calvin was raised by Hansford’s wife, Nancy Tutt. It is said that this is the child that is believed to be the son of Wild Bill and that he later became a police officer in Oklahoma City, but there is no proof that Calvin Lindville was actually Wild Bill’s birth son. However, all research indicates that Calvin was in fact a police office in Oklahoma City.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

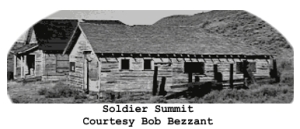

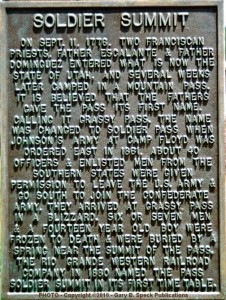

Ghost Town Wednesday: Soldier Summit, Utah

Today’s ghost town was both the name of a Wasatch Mountain pass in Utah and the town which was founded at the top of the pass early in the twentieth century. In 1776 the area was discovered by Francisco Atanasio Domínguez and Silvestre Vélez de Escalante, Franciscan priests, who trekked through the area on their way to present-day California.

Today’s ghost town was both the name of a Wasatch Mountain pass in Utah and the town which was founded at the top of the pass early in the twentieth century. In 1776 the area was discovered by Francisco Atanasio Domínguez and Silvestre Vélez de Escalante, Franciscan priests, who trekked through the area on their way to present-day California.

The name Soldier Summit originated in 1861 when a group of soldiers commanded by General Philip St. George Cooke crossed the pass on their way to join the Confederate Army. Caught in a snow storm in July of 1861, some of them died and were buried on the summit.

Following the Civil War, expansion continued as gold, silver and coal were discovered across the West. Railroads, small and large, were built throughout the region to transport massive quantities of mined materials. The Soldier Summit railroad line was opened by the Utah & Pleasant Valley Railway to transport coal from newly opened mines in Scofield, with a narrow-gauge railway added in 1877 to connect to the Utah Southern Extension Railway.

Following the Civil War, expansion continued as gold, silver and coal were discovered across the West. Railroads, small and large, were built throughout the region to transport massive quantities of mined materials. The Soldier Summit railroad line was opened by the Utah & Pleasant Valley Railway to transport coal from newly opened mines in Scofield, with a narrow-gauge railway added in 1877 to connect to the Utah Southern Extension Railway.

In 1882 the Denver & Rio Grande Western Railway (D&RGW) purchased the U&PV with plans to continue their route to Grand Junction, Colorado. They upgraded the tracks and a new narrow gauge route took the line over Soldier Summit, a climb of four percent grade. In 1890 the line was converted to standard gauge after D&RGW became Rio Grande Western.

The four percent grade heading up to Soldier Summit was a bottleneck, and in 1913 fourteen miles of new line was built between Detour and Soldier Summit. Today that four percent grade route is part of US Highway 6 between Detour and Soldier Summit. Over the years the railroads continued to improve, realign and relocate their routes. One relocation led to the obliteration of the mining town of Thistle in 1983 – you can read about it here in a recent ghost town article.

In 1919 the railroad made Soldier Summit a division point. According to railroad enthusiast Dave Husman:

A division is the portion of the railroad under the supervision of a superintendent. A subdivision is a smaller portion of a division. A subdivision is typically a crew district or a branch line. A division point is just a big yard at one end of the division or another. A regional railroad is basically a cast off portion of a former class one. Division points were important back in the steam era days. Trains would run from division point to division point and completely reswitch and change engines at each division point.

Real estate developer H.C. Mears surveyed the town site, began selling lots and the town was incorporated in 1921. People came to work in the railroad machine shops and growth continued as stores, hotels, restaurants, saloons, churches and a school were built. A branch of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints was established on June 21, 1921, and by 1927 there were enough Mormons living there to organize a ward.

Real estate developer H.C. Mears surveyed the town site, began selling lots and the town was incorporated in 1921. People came to work in the railroad machine shops and growth continued as stores, hotels, restaurants, saloons, churches and a school were built. A branch of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints was established on June 21, 1921, and by 1927 there were enough Mormons living there to organize a ward.

Between 1925 and 1930, the population peaked around twenty-five hundred. Railroad towns, like mining towns which disappeared after mines were depleted, became virtual ghost towns based on the decisions of corporate executives. The railroad realized that the high cost of doing business in Soldier Summit, not to mention the harsh winters, was not cost-effective. In 1930 the division point was moved to Helper and Soldier Summit began to decline.

The town still contributed to the rail line until diesel engines were introduced and the grade was reduced from four to two percent – there was no longer a need for helper engines. In January of 1930 the LDS ward was downgraded once again to a branch. By 1949 the school’s enrollment dropped to just eleven students, although it remained open until 1973.

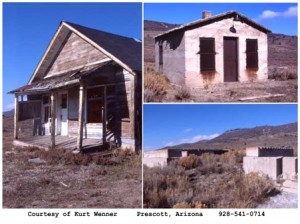

In the late 1970’s there were still a handful of residents and four part-time police officers, but the town was totally disbanded in 1984. Today only a gas station, empty houses and crumbling foundations are all that remain.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Tombstone Tuesday: Dorothy Trimmer Bryant

Dorothy Trimmer Bryant was born to parents Joseph Aaron and Florence Pauline (Schlosser) Trimmer on March 13, 1914 in Glen Rock, York County, Pennsylvania. Her father’s occupation for several years was telephone operator and in 1930 the family was residing in Wrightville, York, Pennsylvania.

Dorothy Trimmer Bryant was born to parents Joseph Aaron and Florence Pauline (Schlosser) Trimmer on March 13, 1914 in Glen Rock, York County, Pennsylvania. Her father’s occupation for several years was telephone operator and in 1930 the family was residing in Wrightville, York, Pennsylvania.

Sometime after the 1930 census the family relocated to Baltimore, Maryland since Dorothy appears in The Eastern Echo yearbook (Eastern High School, Baltimore) in 1932. Her senior class picture implies that she may have joined the class that school year.

The yearbook lists her address as 538 East 22nd Street (I have never heard of a yearbook listing a student’s home address!). Dorothy must have been athletically inclined because it states that “[S]he is going to teach gym in the not too distant future.” Whatever Dorothy decided to do after graduating from high school, however, is unclear since it was difficult to find records which provided residence and occupation data.

Her obituary states that she worked for the Glenn L. Martin Company, the forerunner of one of today’s prominent defense contractors, the Lockheed Martin Corporation. The company had been founded in California in 1912 and merged (briefly) with Wright Company (see my book review of Birdmen for more on the Wright brothers and their rivals) in 1916. The merger was unsuccessful and in 1917 and Glenn Martin founded another Glenn L. Martin Company, basing his operations in Cleveland, Ohio.

Her obituary states that she worked for the Glenn L. Martin Company, the forerunner of one of today’s prominent defense contractors, the Lockheed Martin Corporation. The company had been founded in California in 1912 and merged (briefly) with Wright Company (see my book review of Birdmen for more on the Wright brothers and their rivals) in 1916. The merger was unsuccessful and in 1917 and Glenn Martin founded another Glenn L. Martin Company, basing his operations in Cleveland, Ohio.

The company built bombers which flew in World War I and in 1929 the operations in Cleveland were closed and relocated to the Baltimore metropolitan area in Middle River, Maryland. The company, of course, played a significant role during World War II as the country rallied to mass produce military equipment, both for the United States and its allies. (Don’t miss this week’s Book Review Thursday: The Arsenal of Democracy)

The war in Europe was raging, and although the United States would not formally enter the conflict until December 11, 1941, in October of 1940 men between 21 and 35 began to receive draft notices. Congresswoman Edith Nourse Rogers of Massachusetts introduced a bill in May of 1941 which called for the creation of a volunteer women’s army corp. In May of 1942 a bill passed the House and Senate, creating the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC).

The women who joined the WAAC were not technically in the military, rather they were civilians working with the Army. By the spring of 1943 sixty thousand women had already volunteered, and in July of that year a new congressional bill changed the name to Women’s Army Corps (WAC), making those who volunteered full-fledged members of the military. Whether Dorothy first joined the WAAC or WAC is unclear as her obituary (and her gravestone) merely indicates she was a member of the WAC.

The date she joined is unclear as well since her obituary merely states she served overseas for three years. Her rank was TEC4, or Technician Fourth Grade, which would have placed her in a pay grade similar to that of Sergeant, although not having authority to issue commands or orders.

She married Robert D. Bryant in Frankfurt, Germany on June 5, 1948. Robert, the son of Arthur and Hattie Bryant of Estacado, Texas, had joined the military in 1938. According to the Crosby County TXGenWeb Project, Robert was an engineer who built bridges, contributing significantly during the Battle of the Bulge.

Dorothy’s family had a history of military service dating back to the Revolutionary War. Her brother Joseph, the only surviving family member at the time of her death and mentioned in her obituary, filed an application for the Sons of the American Revolution in 1968. Their ancestor, John Trimmer, was born in 1750 and served in the Sixth Company of the Fifth Battalion of York County, Pennsylvania.

Whether the couple lived overseas until Robert was discharged in 1952 is unclear as no record of his discharge (and for that matter his enlistment) could be found at Fold3 or Ancestry.com. However, the couple did eventually return to live in the Lubbock or Crosby County area where Robert was a farmer. Neither of Robert or Dorothy’s obituaries mentions children so presumably they were childless.

Whether the couple lived overseas until Robert was discharged in 1952 is unclear as no record of his discharge (and for that matter his enlistment) could be found at Fold3 or Ancestry.com. However, the couple did eventually return to live in the Lubbock or Crosby County area where Robert was a farmer. Neither of Robert or Dorothy’s obituaries mentions children so presumably they were childless.

Robert died on May 15, 1983 at Methodist Hospital in Lubbock following a lengthy illness. Dorothy continued to live in the area until she passed away at St. Mary’s Hospital in Lubbock on April 2, 1996. They are both buried in the Estacado Cemetery, having both served their country during World War II as signified by their gravestones.

I should note that today’s article was a bit challenging to research as there was more than one Dorothy Trimmer in York County, Pennsylvania and all were born approximately the same year apparently. I was, however, able to definitively trace parentage after reading her obituary and backtracking to search instead for information on her brother Joseph E. Trimmer.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Mothers of Invention: Bette Nesmith Graham

As the saying goes, “necessity is the mother of invention.” In the late 1940’s single mother Bette Nesmith was an executive secretary at Texas Bank and Trust in Dallas. To cover up her typing mistakes she mixed a batch of tempera water-based paint to match the company’s stationery. She used a thin paint brush to “paint over” her mistakes and her boss couldn’t tell the difference.

As the saying goes, “necessity is the mother of invention.” In the late 1940’s single mother Bette Nesmith was an executive secretary at Texas Bank and Trust in Dallas. To cover up her typing mistakes she mixed a batch of tempera water-based paint to match the company’s stationery. She used a thin paint brush to “paint over” her mistakes and her boss couldn’t tell the difference.

Bette Claire McMurray was born on March 23, 1924 in Dallas, Texas to parents Jesse and Christine (Duval) McMurray. Raised in San Antonio, she married Warren Audrey Nesmith before he departed to serve during World War II. Their son, Robert Michael Nesmith, was born on December 30, 1942. Folks of a certain age will remember him as a member of The Monkees and cast member of a television show of the same name.

Bette Claire McMurray was born on March 23, 1924 in Dallas, Texas to parents Jesse and Christine (Duval) McMurray. Raised in San Antonio, she married Warren Audrey Nesmith before he departed to serve during World War II. Their son, Robert Michael Nesmith, was born on December 30, 1942. Folks of a certain age will remember him as a member of The Monkees and cast member of a television show of the same name.

Warren returned from the war, although he and Bette divorced in 1946. After Bette’s father died and left her some property in Dallas, she returned there and found work as a secretary. IBM electronic typewriters were in usage, but if one small error occurred the entire page had to be retyped – what a waste of time!

She was an amateur artist and while working on a freelance project it occurred to Bette that painters didn’t have to start over when they made a mistake – they simply painted over it. Thus, the idea to mix her own batch of tempera water-based paint. For a time she kept the invention to herself, but other secretaries eventually heard of it, so she began bottling it with the name “Mistake Out”, selling her first bottles in 1956.

She was an amateur artist and while working on a freelance project it occurred to Bette that painters didn’t have to start over when they made a mistake – they simply painted over it. Thus, the idea to mix her own batch of tempera water-based paint. For a time she kept the invention to herself, but other secretaries eventually heard of it, so she began bottling it with the name “Mistake Out”, selling her first bottles in 1956.

She continued to work on Mistake Out at home with the help of her son and a team she recruited to improve the product. By 1957 Bette was selling about one hundred bottles per month. According to Women Invent!: Two Centuries of Discoveries That Have Shaped Our World, she did not patent her invention (although some sources claim she did). Rather she trademarked the name “Liquid Paper”. An article in a stationery magazine highlighting her invention pushed sales higher.

According to the Liquid Paper corporate web site, Bette was fired from the bank in 1958. The timing couldn’t have been better because the product had been perfected by then and sales were substantial enough that she could afford to devote her time to the business of selling Liquid Paper, albeit working out of her home instead of an office. Part-time employees were hired and by 1961 she hired her first full-time employee.

According to the Liquid Paper corporate web site, Bette was fired from the bank in 1958. The timing couldn’t have been better because the product had been perfected by then and sales were substantial enough that she could afford to devote her time to the business of selling Liquid Paper, albeit working out of her home instead of an office. Part-time employees were hired and by 1961 she hired her first full-time employee.

In 1962 Bette married Robert Graham and he helped to run the company. The couple later divorced in 1975. By 1967 the company had its own corporate headquarters and production facilities. Sales were soaring in excess of one million units per year in 1975, prompting another move to an even larger facility – thirty-five thousand square feet – in Dallas. The new headquarters included a library and childcare center.

In 1979 Bette sold Liquid Paper to the Gillette Corporation for $47.5 million. At that time the company employed two hundred people who produced twenty-five million bottles of Liquid Paper per year. Unfortunately, Bette Nesmith Graham passed away the following year on May 12, 1980 at the age of fifty-six. Her son Michael inherited half of her sizable estate.

The product continued to sell well for Gillette, which later added correction pens and tape to the product line. In 2000 the Liquid Paper brand was acquired by Newell Rubbermaid and new products continue to be introduced. All in all, an amazing success story of a single mother with only a high school education who went on to become a multi-millionaire – and we think to ourselves, “Why didn’t I think of that!?!”

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

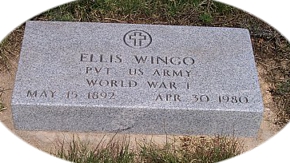

Surname Saturday: Wingo

I ran across this surname while walking through a prairie cemetery in Lubbock County, Texas:

My curiosity was piqued to find out its origins.

My curiosity was piqued to find out its origins.

As always there will be more than one opinion as to a surname’s origin – here are three theories:

One source believes that the name was locational in Berkshire. Possible spelling variations were Wingrove, Winger, Wingrave and Winge. An early instance of the name “Witungraue” (no surname) was recorded in the 1086 Domesday Book, which would have derived from an Olde English word – wioig (a willow) and graf (a grove).

Another source purports that the name was a variation of the following names: Winpenny, Wimpenny, Wimpory, Wimpery, Wimpeny, Wynngold and more. Yet another source, The Dictionary of American Names, indicates that the name is likely an Anglicized version of the French Huguenot name “Vigneau.” Their evidence for believing the surname is of French origin:

Another source purports that the name was a variation of the following names: Winpenny, Wimpenny, Wimpory, Wimpery, Wimpeny, Wynngold and more. Yet another source, The Dictionary of American Names, indicates that the name is likely an Anglicized version of the French Huguenot name “Vigneau.” Their evidence for believing the surname is of French origin:

A habitational name for someone from a place so named in Vienne, or from places in Aube and Indre called Les Vigneaux, or

A status name for the owner of a vineyard, from a derivative of Occitan vinhier “vineyard”. This is found as a Huguenot name.

The latter explanation actually seems more plausible after finding evidence offered by family historians who have found records of the Wingo surname appearing in or near Manakin, a Huguenot settlement in Virginia. According to The Huguenot Society of the Founders of Manakin in the Colony of Virginia web site, French Huguenots began arriving in Virginia as early as 1620. Like many early settlers, the Huguenots were fleeing religious persecution.

A quick check of census records for Ellis Wingo reveals that his grandparents were born in South Carolina. In 1679, King Charles II sent two shiploads of French Huguenots to South Carolina for the purpose of cultivating grapes, olives and silkworms. One family history researcher found evidence in a book called Irish Pedigrees or the Origin and Stem of the Irish Nation which lists the names of refugees who settled in Britain and Ireland during Louis XIV’s reign. Louis XIV’s persecution of Huguenots began in 1685 but the name Vigneau had already been found in England long before that. One name listed was “De Vinegoy”.

So it’s possible that Ellis Wingo’s ancestors may have been French Huguenots. This is what I love about history – just one glimpse of an unusual surname on a grave stone and a little research – a little “diggin’ history”. I don’t think I’ll ever run out of material! Look for more articles later from my visit to historic Estacado Cemetery.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

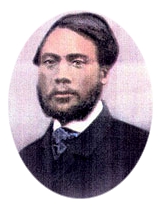

Feisty Females (and Fellows): Ellen and William Craft

In December of 1848 a man and woman, both born into slavery, devised a scheme – a ruse – which would lead them to freedom. Their reason for embarking on such a daring adventure was later eloquently stated in the opening lines of their memoir, Running A Thousand Miles:

In December of 1848 a man and woman, both born into slavery, devised a scheme – a ruse – which would lead them to freedom. Their reason for embarking on such a daring adventure was later eloquently stated in the opening lines of their memoir, Running A Thousand Miles:

Having heard while in Slavery that “God made of one blood all nations of men,” and also that the American Declaration of Independence says, that “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights; that among these, are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness;” we could not understand by what right we were held as “chattels.” Therefore, we felt perfectly justified in undertaking the dangerous and exciting task of “running a thousand miles” in order to obtain those rights which are so vividly set forth in the Declaration.

Ellen Craft, the light-skinned daughter of Maria and her white master, Colonel James Smith – and the half-sister of Smith’s other children – was born in Georgia in 1826. Often mistaken for one of Smith’s white children, and said to have been a great annoyance to the colonel’s wife, eleven year-old Ellen was given to her half-sister as a wedding present in 1837.

William Craft was put up for auction at the age of sixteen to settle his master’s debts and purchased by a bank cashier. William, a skilled carpenter, continued to work for a cabinet maker but following the auction his new owner took most of his wages. His parents and brother had been sold, locations unknown, and just before William had been sold he witnessed the sale of his tearful fourteen-year old sister.

William Craft was put up for auction at the age of sixteen to settle his master’s debts and purchased by a bank cashier. William, a skilled carpenter, continued to work for a cabinet maker but following the auction his new owner took most of his wages. His parents and brother had been sold, locations unknown, and just before William had been sold he witnessed the sale of his tearful fourteen-year old sister.

William and Ellen met, fell in love and were married in 1846, although not allowed to live together because they served different masters. The separation was difficult but William and Ellen knew if children were born to their marriage they would likely be taken away from them. The thought, William wrote, “filled my wife with horror.”

Admittedly, William and Ellen’s situation wasn’t as bad as some who were enslaved in the South. Rather, it was the thought that as chattels they were deprived of their legal rights, giving their wages to “a tyrant, to enable him to live in idleness and luxury – the thought that we could not call the bones and sinews that God gave us our own; but above all, the fact that another man had the power to tear from our cradle the new-born babe and sell it in the shambles like a brute, and then scourge us if we dared to lift a finger to save it from such a fate, haunted us for years.” (Running a Thousand Miles, p. 2)

Clearly, they believed something better awaited them in the North if they could devise a successful escape from Georgia. From his work as a carpenter, William was able to save some of the wages, small though they may have been. By December of 1848 they began to seriously discuss various plans. Using the premise that slaveholders were allowed to take their slaves to other states, whether those states were slave or free, led to a carefully-crafted ruse.

Clearly, they believed something better awaited them in the North if they could devise a successful escape from Georgia. From his work as a carpenter, William was able to save some of the wages, small though they may have been. By December of 1848 they began to seriously discuss various plans. Using the premise that slaveholders were allowed to take their slaves to other states, whether those states were slave or free, led to a carefully-crafted ruse.

Because Ellen was so fair-skinned the plan was to disguise her as a young white man since it would have been unusual for a young woman to travel with a male slave and certainly would have drawn unwanted attention. Ellen’s first reaction was one of panic, although as they talked she eventually warmed to the idea. Their plan was to ask for passes at Christmastime, something that slaveholders often granted to favored slaves.

On December 21, William cut Ellen’s long hair to neck-length. In order to disguise the lack of a beard her face was bandaged, and to disguise the fact she couldn’t read or write, her arm was placed in a sling since she (“he”) would have been asked to sign a hotel register. The bandage around her face would perhaps discourage strangers from wanting to converse. Ellen made a pair of men’s trousers, donned a top hat and chose a pair of green spectacles to further disguise herself. The hat and glasses had to be purchased so the disguise alone, save the trousers she sewed, was risky since it was forbidden for slaves to trade without their master’s consent.

On December 21, William cut Ellen’s long hair to neck-length. In order to disguise the lack of a beard her face was bandaged, and to disguise the fact she couldn’t read or write, her arm was placed in a sling since she (“he”) would have been asked to sign a hotel register. The bandage around her face would perhaps discourage strangers from wanting to converse. Ellen made a pair of men’s trousers, donned a top hat and chose a pair of green spectacles to further disguise herself. The hat and glasses had to be purchased so the disguise alone, save the trousers she sewed, was risky since it was forbidden for slaves to trade without their master’s consent.

Before leaving for the Macon train station the couple peeped out the window of the cottage to make sure no one was observing their movements. William whispered to his wife, “Come my dear, let us make a desperate leap for liberty!” Ellen, still in a panic, shrank back and began to sob. William assured her the plan was the only way to gain their freedom, and after a few encouraging words and a silent prayer she was able to continue.

After stepping out they shook hands and headed in different directions to the rail station. From that point on William would refer to Ellen as his master – even in his memoir William referred to Ellen as a “he.” Ellen purchased their tickets to Savannah and boarded the train. William had already hopped aboard the negro car and while waiting for the train to depart noticed his employer standing on the platform.

Of course, William feared the worst and expected at any moment to be caught. The cabinet maker looked around in Ellen’s car and headed to the negro car, but just in the nick of time the train departed and the Crafts were on their way. William later learned that his employer had heard a rumor about their planned escape, but by the time the rumor was confirmed the Crafts were safe in a northern free state.

Ellen had her own moment of panic while observing the other passengers in her car. She noticed a good friend of her master sitting nearby – he had known Ellen since her childhood! Like William, she assumed that he was there to capture her, but when Mr. Cray tried to start a conversation, Ellen looked away and feigned deafness. Cray got the hint and began conversing with others nearby – in the words of William Craft he began discussing “Niggers, Cotton, and the Abolitionists.” I’m sure Ellen breathed a sigh of relief when he exited the train at Gordon.

After the train arrived in Savannah the next step was to board a steamer bound for Charleston, South Carolina. Again, Ellen, posing as an ailing white gentleman, was able to easily board while William was consigned to walk about the deck and then rest on a pile of cotton bags until morning. Because his master was “invalid” William was allowed to accompany him to breakfast and help attend to him.

Lo and behold, Ellen was seated at the captain’s table and he (the captain) warned that Ellen should watch William like a hawk as he might get other ideas when they reached the North. A crude man, a slave dealer, interrupted and provided his own opinions: “I would not take a nigger to the North under no consideration. I have had to deal to do with niggers in my time, but I never saw one who ever had his heel upon free soil that was worth a damn.” Imagine the restraint it must have taken Ellen and William to resist responding to such crude sentiments! Instead, Ellen thanked the captain for his advice and walked out on deck to await the ship’s arrival in Charleston.

After arriving in Charleston the plan had been to continue on to Philadelphia by steamer, but they soon found there were no vessels traveling that route in the winter. Instead they took a steamer to Wilmington, North Carolina and then continued on to Richmond, Virginia via train. By Christmas Eve they had reached Baltimore, the last significant slave port before reaching a free state. Knowing that citizens and law enforcement were especially watchful of slaves attempting to reach Pennsylvania, William and Ellen were extra vigilant.

Their plans to board a train and head to Pennsylvania were almost thwarted when a railroad officer informed them that William had no right to accompany his master – another panicky moment. He thought to himself “that the good God, who had been with us thus far, would not forsake us at the eleventh hour.” After explaining the situation to Ellen they proceeded to the rail office to obtain permission to continue on together in their travels. “But, as God was our present and mighty helper in this as well as in all former trials, we were able to keep our heads up and press forwards.”

Ellen stated their case and convinced the officer that because of her injured arm she was unable to sign any documents (remember, in fact, she could neither read nor write) and after some deliberation the couple was allowed to board the train and continue their flight to freedom. Since leaving Macon three nights before the Crafts had very little opportunities for sleep, so William thought he would take a nap. However, he slept too soundly and when the train made a stop Ellen wondered where he was – quite naturally her first thought was that William had been captured and their plan had fallen apart. He was later found by a guard and hurried to assure his master that all was well.

The completion of their journey was at hand, William rejoicing and thanking God for protection and mercy. Upon arrival in Philadelphia he hurried to retrieve his master, or rather his wife, as he could now refer to her. After boarding a cab, she turned to William and exclaimed, “Thank God, William, we are safe!” – and promptly burst into tears. It was Christmas Day.

They were able to quickly connect with the underground abolitionist network in Philadelphia. Their first host was Barkley Ivens, a Quaker, and his family. Although somewhat nervous following their harrowing escape, the Crafts agreed to accept Ivens’ hospitality. Ellen’s fears were immediately allayed when she walked into the Ivens home and Mrs. Ivens assured her, “Ellen, I shall not hurt a single hair of thy head. We have heard with much pleasure of the marvelous escape of thee and thy husband, and deeply sympathise with thee in all that thou hast undergone. I don’t wonder at thee, poor thing, being timid; but thou needs not fear us; we would as soon send one of our own daughters into slavery as thee; so thou mayest make thyself quite at ease!”

After a sumptuous supper, the Ivens inquired as to whether Ellen and William could read. Upon finding they were illiterate, the Ivens family offered to teach them to read and write – now! The table was cleared and out came the spelling and copy books, pencils and slates. Both Ellen and William had a rudimentary knowledge of the alphabet but not the ability to write the characters. Even though they wondered whether at their advanced age they could learn, the Ivens family was insistent that they continue. After three weeks, Ellen and William were able to spell and write their names quite well.

Their plan was to continue on to Boston, but their parting with the Ivens family was bittersweet, having found friends who in a short time became like family to them. After settling in Boston, the Crafts found work, he as a cabinet maker and she as a seamstress. All was well until 1850 when the Fugitive Slave Bill was passed by Congress.

The new law mandated that persons in free states could no longer provide aid and comfort to fleeing slaves. Instead they would be compelled to report them so they could be returned to their masters. The Crafts’ former masters sent agents to find them, took out warrants and placed them in the hands of the United States Marshal. However, the Reverend Samuel May, a Boston minister, intervened with a letter outlining Ellen and William’s plight, including their daring escape two years earlier.

Still, their masters pressed for the Crafts’ return. After much deliberation, William and Ellen Craft decided to flee their country and migrate to Britain – slavery had been abolished there in 1833. Not until they reached Britain’s shores did they feel “free from every slavish fear.” They were aided by abolitionists who arranged for them to receive an education in Surrey. In 1852 Ellen, having learned to read and write quite well, published a pamphlet which was circulated widely in both Britain and the United States:

So I write these few lines merely to say that the statement is entirely unfounded, for I have never had the slightest inclination whatever of returning to bondage; and God forbid that I should ever be so false to liberty as to prefer slavery in its stead. In fact, since my escape from slavery, I have gotten much better in every respect than I could have possibly anticipated. Though, had it been to the contrary, my feelings in regard to this would have been just the same, for I had much rather starve in England, a free woman, than be a slave for the best man that ever breathed upon the American continent.

Ellen and William Craft had five children and remained in England for almost two decades before making the decision, despite what she wrote in 1852, to return to their homeland following the Civil War’s conclusion. Two of their children remained in England. In 1870 they purchased eighteen hundred acres of land near Savannah and founded the Woodville Cooperative Farm School in 1873. Ku Klux Klan members had burned their first plantation in South Carolina, and following white opposition in Georgia, resulting in bankruptcy, the school was closed in 1878.

The Crafts moved to Charleston in 1890 to live with their daughter Ellen. Ellen Craft passed away in 1891 and William in 1900. She had overcome so much in her life and in 1996 Ellen Smith Craft was named as a Georgia Woman of Achievement. If you would like to read more about Ellen and William Craft, you will find a free on-line version here – just 111 pages and an enlightening read.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Wild West Wednesday: Vigilante X

Historical accounts vary as to whether today’s Wild West character came by his name via the middle name of “Xavier” or it was a family nickname, or he just adopted “X” as his name after becoming a well-known member of the Montana Vigilantes. Following the big 1863 gold strike in Alder Gulch, waves of miners flooded the region and settled along an area known as the “Fourteen Mile City” – see last week’s Ghost Town article here for more background.

Historical accounts vary as to whether today’s Wild West character came by his name via the middle name of “Xavier” or it was a family nickname, or he just adopted “X” as his name after becoming a well-known member of the Montana Vigilantes. Following the big 1863 gold strike in Alder Gulch, waves of miners flooded the region and settled along an area known as the “Fourteen Mile City” – see last week’s Ghost Town article here for more background.

The man who became known as “Vigilante X”, John Beidler, was born on August 14, 1831 in Pennsylvania to parents John and Anna Hoke Beidler. His father died in 1849 and his mother around 1850 before the census enumeration in August of that year. That year John was eighteen and his occupation was that of shoemaker.

John was a supporter of abolitionist John Brown and sometime in the 1850’s he made his way to Kansas to try his hand at farming. That means he would have been on hand during the period known as “Bloody Kansas”. Following Brown’s death by hanging for his part in the raid on Harper’s Ferry, John left Kansas for Texas.

John was a supporter of abolitionist John Brown and sometime in the 1850’s he made his way to Kansas to try his hand at farming. That means he would have been on hand during the period known as “Bloody Kansas”. Following Brown’s death by hanging for his part in the raid on Harper’s Ferry, John left Kansas for Texas.

From Texas he moved on to Colorado, and then news of gold strikes in what would soon be Montana Territory compelled John northward in 1863. According to the Society of Montana Pioneers, John arrived in Virginia City on June 10, just days after the discovery made by a group of miners. As was the case all over the West during that era, very little formal law enforcement existed in the boom towns which sprung up, and Virginia City was no exception.

Minor legal matters were handled by informal miner’s court proceedings, but for major crimes such as looting, robbery and murder there was no official law enforcement. One gang was led by Henry Plummer, who although a lawbreaker, somehow convinced the town of Bannack to elect him sheriff – History.com refers to him as a “charming psychopath.”

In defiance of the lawlessness, a secret vigilance committee was formed with concerned citizens of Virginia City and Bannack. After joining the Vigilantes, Beidler became one of its most active members and in December of 1863, along with twenty-four men, swore a secret oath. Their mission was to hunt down, capture and hang as many of the criminals, Plummer included.

The Vigilantes thought the only way to restore law and order was to completely rid the area of Plummer and his gang. In January and February of 1864 twenty-one men were captured and hanged – no trials, no appeals and no time to put one’s affairs in order.

Prior to the formation of the vigilance committee, one man, George Ives, did receive a jury trial after he was accused of murdering Nicholas Tbalt, a young man whose parents had been killed by Indians. During the trial Beidler stood guard over the proceedings. After Ives was convicted following a three-day trial, he pleaded for a stay of execution. From the rooftop above the proceedings, Beidler shouted out to the prosecutor, “Ask him how much time he gave the Dutchman!” George Ives was hanged that evening.

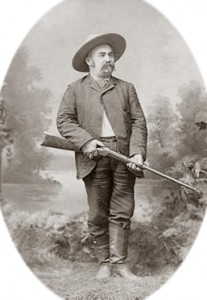

As more or less the face of the Vigilantes, Beidler or “Vigilante X” as he liked to be called, was accused of stepping over the line. Some lauded him as being trustworthy and fearless – others believed he was nothing more than a “pint-size bully” and braggart. As Jon Axline points out in his book Still Speaking Ill of the Dead: More Jerks in Montana History, he was a complex personality and all of those things, positive or negative, could be said of him.

Another description of him from Frederick Allen’s book A Decent, Orderly Lynching: The Montana Vigilantes: “John Xavier Beidler, known to one and all by his middle initial, “X,” was an energetic little plug of a man, shorter than his rifle at five-foot-three.” In his own words, Beidler described his penchant for impatience regarding delays, saying it would make him become “boiling, you bet, and indignant into the bargain.” He often dressed in clothes too big for his “squatty-body” and Axline points out that he had the “less savory” trait of taking items, including clothing, from corpses for his own use.

Another description of him from Frederick Allen’s book A Decent, Orderly Lynching: The Montana Vigilantes: “John Xavier Beidler, known to one and all by his middle initial, “X,” was an energetic little plug of a man, shorter than his rifle at five-foot-three.” In his own words, Beidler described his penchant for impatience regarding delays, saying it would make him become “boiling, you bet, and indignant into the bargain.” He often dressed in clothes too big for his “squatty-body” and Axline points out that he had the “less savory” trait of taking items, including clothing, from corpses for his own use.

Later in 1864, Beidler was appointed as a deputy U.S. marshal but continued his vigilante activities which led many to accuse him of overstepping the bounds of established law and justice. While serving as a law enforcement official he simultaneously helped to organize a vigilance committee in Helena. By 1867 he found plenty of work in Helena which was infested with a criminal element – practically every day there were reports of robberies and murders.

In 1870 his penchant for crossing the line almost resulted in his being arrested for murder. In January a Chinese miner by the name of Ah Chow had killed a man in Helena. When Beidler captured the Chinaman, he returned his prisoner to Helena and turned him over to the vigilantes who promptly hanged him. Beidler applied for Chow’s bounty, which raised the ire of the local paper’s editor:

We could not believe that any mere private citizens would engage in so lawless a proceeding and then have the temerity to acknowledge his guilt by applying for and receiving the reward.

Beidler claimed that he was thereafter threatened, allegedly receiving a note warning him, “We . . . will give you no more time to prepare for death than the many men you have murdered . . . . We shall live to see you buried beside the poor Chinaman you murdered.”

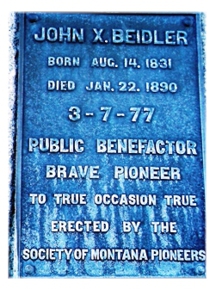

John Beidler continued to served as deputy U.S. marshal until the late 1880s. In 1888 his health began to fail, and being destitute, relied on the charity of friends. On January 22, 1890 he died at the Pacific Hotel in Helena from complications of pneumonia. Hundreds of friends and associates attended his funeral, paid for by contributions. The Great Falls Weekly Tribune summed up his life: “He dies poor, having served his territory much better than he served himself. Peace to his ashes.”

In 1903 his body was exhumed by the Montana Society of Pioneers and moved to Forestvale Cemetery. A “great rough boulder, emblematic of his rugged character” was later erected over his grave and inscribed with a plaque:

Even though he was known for his “extra-legal” vigilante activities, apparently the historical society and the annals of Montana history have chosen to honor him regardless. He was definitely one-of-a-kind.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!