Ghost Town Wednesday: Stiles, Texas

“It isn’t likely that a tourist will ever see the old Reagan County Courthouse at Stiles unless he is looking for it, or just flat lost.” That’s what a contributor on the Ghost Towns web site had to say about Stiles, Texas. It’s a bit off the beaten track these days.

“It isn’t likely that a tourist will ever see the old Reagan County Courthouse at Stiles unless he is looking for it, or just flat lost.” That’s what a contributor on the Ghost Towns web site had to say about Stiles, Texas. It’s a bit off the beaten track these days.

Stiles had a storied history dating back to the mid-seventeenth century when Captains Diego del Castillo and Hernán Martin were sent out to explore an area which would later be Texas. Castillo and Martin passed through the area and camped a night or two near where Stiles was eventually located near the Centralia Draw. A short-cut to the Santa Fe Trail would later be carved out nearby as well.

Around 1890 Gordon Stiles and Gerome W. Shields came to the area and were later joined by P.H. Coates, a rancher who had already begun building a sheep ranch in the 1880’s. In 1894, Stiles submitted an application for a post office which was accepted. By the early 1900’s the area had increased enough in population to warrant a split from Tom Green County.

Around 1890 Gordon Stiles and Gerome W. Shields came to the area and were later joined by P.H. Coates, a rancher who had already begun building a sheep ranch in the 1880’s. In 1894, Stiles submitted an application for a post office which was accepted. By the early 1900’s the area had increased enough in population to warrant a split from Tom Green County.

In 1903, by a vote of 40-1, Reagan County was formed. Since no other village or town of any size existed, Stiles was the natural choice as county seat and the location of the county courthouse. An amusing story about the county’s founding was related in a 1964 article by Joe Mosby in the Big Springs Daily Herald:

The move for forming the new county had a brush with disaster, though. Texas statutes required that a petition for a new county had to be submitted bearing names of a percentage of residents of the area. Promoters of the petition for Reagan’s formation fell two names short, and there was despair for a moment. But at the last minute the signatures reading “John Donohu” and “Bill Donohu” were added. No one said much, but John and Bill were the names of a pair of outstanding mules that had labored hard in the early days at Stiles. “Donohu” had a mighty similar sound to “Do Know Who” so the settlers later chuckled.

Before a permanent courthouse was built, Sheriff Henry Japson would chain prisoners to a hitchrack. As Mosby related in his article, “[O]ne later prominent citizen of the area vows that the end of his drinking days came right there at that hitchrack.” When the bond election to fund the courthouse and jail was held in August of 1903, the results were the same as the election to form the county – 40-1.

A frame building replaced the temporary structure, but by 1911 an even more substantial two-story structure was built. Gordon Stiles owned the general store where the many of the town’s activities were centered, so the town was named after him. The land where the permanent courthouse was built had been donated by Stiles and Shields.

The new courthouse, constructed of stone quarried from the Centralia Draw, was said to have been the nicest in West Texas at the time, perhaps valued as much as $25,000. By this time, there were also around one hundred homes in Stiles, along with a newspaper and telephone service. All Stiles needed to prosper and survive long-term would have been railway access.

The new courthouse, constructed of stone quarried from the Centralia Draw, was said to have been the nicest in West Texas at the time, perhaps valued as much as $25,000. By this time, there were also around one hundred homes in Stiles, along with a newspaper and telephone service. All Stiles needed to prosper and survive long-term would have been railway access.

In 1910 the Kansas City, Mexico and Orient Railroad wanted to run their line from San Angelo through Stiles to Fort Stockton and Toyahville. However, one of the largest landowners in Reagan County refused to grant access across his land. The rail line instead was located about twenty miles south near a big lake (said to be full of huge catfish and alligators). The result? The town of Big Lake was established in 1912 and by 1919 was approximately the same size as Stiles.

But, of course, Big Lake had a railroad and Stiles had lost out. For several years, Big Lake fought to become the new county seat. Their fate and that of Stiles seemed to have been sealed, however, when in 1923 the Santa Rita oil well just west of Big Lake brought more people to the area and a booming economy. The oil strike also greatly benefited the University of Texas – quite a bit of the land in Reagan county was owned by the school.

In 1925 the vote finally swung in favor of Big Lake (292-94) and Stiles began to decline. The abandoned courthouse served as a school, and a sometimes community center and dance hall for a time. Mosby reported in 1964 that the building served as storage for the county road department and residence for a county worker. It’s only governmental function at that time was its use as a voting precinct.

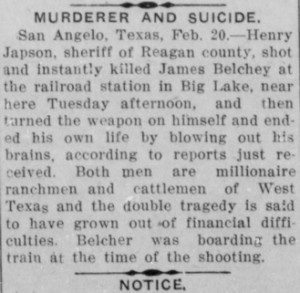

One tragic event marred the history of Stiles, however. Henry Japson had served as the county sheriff for years – in fact the only sheriff the county had ever employed – and was said to have been quite wealthy. He was a long-time friend of James Belcher, an English immigrant who had built a prosperous ranching operation in the area and was himself quite wealthy.

In 1964, in a retraction of sorts to Mosby’s January 26 article, James Belcher’s daughters stated that they believed a disagreement had arisen over the recent appointment of their father to represent the Drover Cattle Loan Company of Kansas City, a post which Henry Japson had previously held. According to the daughters, the two men had encountered one another in the county clerk’s office on February 19, 1918.

As Belcher stepped out into the hallway, shots were fired by Japson and Belcher fell dead. Sheriff Japson was said to have gone to his car, returned to his office, shut the door and then killed himself, or as one newspaper related it – he blew his brains out.

According to the Texas Escapes web site, someone tried to set the courthouse on fire in 1999. The building is now gutted and appears to be surrounded by a security fence. Historical markers have been placed near the courthouse and at the Stiles Cemetery. To reach the abandoned town site, head north on Highway 37 out of Big Lake and at 12.5 miles make a hard left turn. The courthouse will be on the south side of the highway.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Mothers of Invention: Patsy O’Connell Sherman

Today’s “mother of invention” article features another “parent-friendly” product (last week it was disposable diapers). As you will see, she could also be characterized as a “feisty female”.

Today’s “mother of invention” article features another “parent-friendly” product (last week it was disposable diapers). As you will see, she could also be characterized as a “feisty female”.

Patsy O’Connell Sherman was born on September 15, 1930 in Minneapolis, Minnesota to parents James and Edna O’Connell. During her high school years, Patsy took an aptitude test which showed her best career choice would that of housewife. In that day, how many young women do you think received that same recommendation? Patsy, however, refused to accept that result and demanded to take the boy’s aptitude test.

According to the Minnesota Science and Technology Hall of Fame, she wanted to attend college but certainly didn’t want to spend all that time and money educating herself only to become a housewife. The aptitude test for boys revealed a much different career path – she would be well-suited to be either a dentist or a scientist.

According to the Minnesota Science and Technology Hall of Fame, she wanted to attend college but certainly didn’t want to spend all that time and money educating herself only to become a housewife. The aptitude test for boys revealed a much different career path – she would be well-suited to be either a dentist or a scientist.

In 1952 Patsy graduated from Gustavus Adolphus College with a Bachelor of Science degree in chemistry and mathematics – and the first female attending the school to do so. As an example of how things have drastically changed, after graduating Patsy took a “temp job” at Minnesota-based 3M Corporation. She was contracted to assist in developing a new type of fuel line for jet aircraft through the use of fluorochemicals. The reason her job was considered temporary? At that time women hired to work in laboratories were considered temporary employees, assuming they would leave to get married and have a family.

In 1953 while working on the fuel line project, a lab assistant spilled some of the chemicals she had been experimenting with on her white canvas shoes. Attempts to clean off the spilled drops were unsuccessful, but she noticed that later the area where the chemicals had spilled were clean while other parts of her shoes where dirty.

She and fellow scientist Samuel Smith worked together and on April 13, 1971 received approval for United States Patent 3574791 for “invention of block and graft copolymers containing water-solvatable polar groups and fluoroaliphatic groups.” The fluorochemical polymer that Patsy and Samuel developed was marketed by 3M under the trademark name of Scotchgard™. Development of their invention presented another challenge for Patsy, however – at that time women weren’t allowed to be inside the textile mill where performance tests were conducted.

3M continued to develop the Scotchgard™ line of products and Patsy received sixteen other patents, sharing thirteen of them with Samuel Smith. Patsy was the first person to develop an “optical brightener” – something that gave detergent manufacturers the right to boast that clothes washed in their product would be “whiter than white.”

Patsy O’Connell married Hubert Sherman and had children, but she defied the “norm” and remained at 3M her entire career. By the time she retired in 1992, she had advanced through the ranks and was manager of technical development. She received several prestigious honors throughout her career and beyond, including induction into 3M’s Carlton Society (1974) which honors the company’s best scientists, the Minnesota Inventors Hall of Fame (1989) and the National Inventors Hall of Fame (2001).

Her husband died in 1996 and Patsy died on February 11, 2008. She apparently passed on her love of science to her two daughters – one is a chemist at 3M and the other a biologist. Patsy Sherman, the “accidental inventor” once remarked:

You can encourage and teach young people to observe, to ask questions when unexpected things happen. You can teach yourself not to ignore the unanticipated. Just think of all the great inventions that have come through serendipity, such as Alexander Fleming’s discovery of penicillin, and just noticing something no one conceived of before.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Surname Saturday: Tinker

Most sources agree that today’s surname is of occupational origins, perhaps referring to someone who was a mender of pots and pans (“tinner”). The earliest individuals bearing a particular surname, especially an occupational one, were usually employed in that profession. The occupational name passed to succeeding generations even if the occupational tradition was not, especially after The Middle Ages.

The Internet Surname Database disagrees with the type of occupation, believing that the name did not necessarily refer to someone who mended pots and pans, but perhaps one who sold them – a peddler. Their premise is that the name derived from the Middle English word “tink(l)er” because “they made their approach known by tinking, by either ringing or making a tinkling noise.” Another reason for their theory is that during King Edward VI’s reign a law was passed basically outlawing peddling: “No person or persons commonly called Pedler, Tynker, or Pety Chapman, shall wander or go from one towne to another . . . and sell pynnes, poyntes laces, gloves, knyves, glasses, tapes, or any suche kynde of wares whatsoever or gather connye skynnes.”

A person bearing this surname was recorded in 1244 in “The History Of St. Bartholomew’s Hospital”, but one of the first instances may have been recorded in 1243, during King Henry III’s reign, in County Somerset for Robert le Tinker. The name may also have appeared as “Tinkler” at times – Edward Tinkler was listed in the Yorkshire Poll Tax of 1379.

Thomas Tinker

Thomas Tinker, thought to have been the first Tinker to come to America, was a passenger on the Mayflower and made the journey because of religious persecution. Before their arrival in the New World, forty-three Pilgrims signed their names on November 11, 1620 to a document called the “Mayflower Compact” which would govern the settlers. His name is also inscribed on the Plymouth Rock Monument.

The Compact had been signed while still on board the ship and the original intent was to disembark in the colony of Virginia, but storms forced them to take refuge in Cape Cod, Massachusetts, later named Plymouth after the port city in County Devonshire.

The Compact had been signed while still on board the ship and the original intent was to disembark in the colony of Virginia, but storms forced them to take refuge in Cape Cod, Massachusetts, later named Plymouth after the port city in County Devonshire.

Thomas, his wife and son were likely English separatists who had resided in Leiden, Holland for a time to escape persecution. Thomas Tinker was a wood sawyer by trade. The names of his wife and son were not noted, recorded by William Bradford as “Thomas Tinker, and his wife and a sone.”

The journey was not an easy one and two deaths occurred before landing in Massachusetts. Sickness had already been rampant and upon arrival the Pilgrims were faced with even more challenges. Sadly, Thomas Tinker and his family all perished – “all dyed in the first sicknes” according to William Bradford. That would have occurred sometime between December 1620 and January 1621, but no specific date was recorded for the Tinker family’s death. They were likely buried in unmarked graves in an area referred to today s “Cole’s Hill”.

John Tinker

John Tinker was born in England around 1614 perhaps and his name began to appear in Boston records around 1635. It’s possible that John’s parents also immigrated around the same time. In 1639, while away in England, John wrote a letter to John Winthrop, governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony and enclosed a letter for his mother.

It appears that John Tinker was a well-educated man who had obtained a social position worthy of being addressed as either “Mr. Tinker” or “Master Tinker”. Records show that he was a merchant or trader as well as an attorney. John married Mrs. Sarah Barnes, a divorceé with two daughters (her husband had deserted his family), but it’s unclear when their marriage occurred.

Curiously, her divorce from William Barnes was not recorded until 1649 – and Sarah died in 1648. Following her death, the care of her daughter Mary was entrusted to Richard Cooke, a tailor in Boston and Alice was cared for by John Tinker. Some speculate that perhaps Cooke was Mary’s uncle, his wife being Sarah’s sister.

Sometime prior to December 9, 1649 John married his second wife Alice Smith (Alice signed her name “Alice Tinker” as witness to a land transaction on that date). In 1654 John was made a freeman and in 1655 was offered a sizable piece of property in Lancaster, Massachusetts in exchange for his governmental service as the town’s clerk. In 1659 he and his family removed to Pequot in the Connecticut Colony.

In Pequot John was again active in governmental as well as church affairs. Not long after his arrival the minister of the First Congregational Church in New London departed and John filled in until a new pastor arrived.

While serving as the Chief Magistrate of New London’s Court, John refused to prosecute someone who had spoken out against the King of England. Three of his fellow citizens took exception and charged him with treason, after which John charged them with defamation.

The suit went to the General Court at Hartford, but before it could be settled John Tinker died in October of 1682. The Court, however, regarded those charges as attempts to malign Tinker’s character and levied fines against his accusers. Out of respect for his reputation, the expenses of John Tinker’s illness and funeral were borne by the Colony of Connecticut.

One more Tinker story. In 1663, too long after John’s death, his wife Alice was found to be “with child.” Of course, this type of thing was not tolerated in the Puritan community and Alice had to appear before the General Court. Before the Court she shockingly admitted that the father of her child was Jeremiah Blinman, son of a former minister. Apparently, Alice only paid a fine – otherwise she could have been subjected to more stringent and obvious forms of punishment (think “scarlet letter”). Jeremiah also paid a fine in 1663.

As it turns out though, Jeremiah was not the father, but a married man by the name of Samuel Smith, a New London commissioner. Samuel deserted his wife and moved to Virginia before Alice’s baby was born – records and depositions seem to indicate that he admitted responsibility after his wife Rebecca filed for divorce on the grounds of desertion. The divorce was finalized in 1667.

Meanwhile, Alice Tinker had married another man, an attorney by the name of William Measure, in 1664. Alice, her five children by John Tinker and William Measure moved to Lyme, Connecticut soon after their marriage and remained there until their deaths.

What happened to the illegitimate child? Sarah Tinker was born in Lyme in 1664 (whether before or after Alice’s wedding to Measure is unclear). A record exists in the land records of Lyme listing Sarah as the “daughter of John Tinker”, entitling her to an allowance of land equal to that of any heir of the land’s original owner.

Sources:

Descendants of James Stanclift of Middletown, Connecticut and Allied Families, by Robert C. and Sherry [Smith] Stancliff

The Ancestors of Silas Tinker in America from 1637, by A.B. Tinker (1889)

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

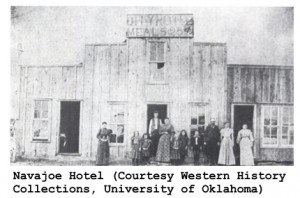

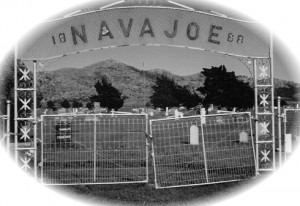

Ghost Town Wednesday: Navajoe, Oklahoma

Some historians credit Joseph S. “Buckskin Joe” Works, a Texas land promoter, with the founding of today’s ghost town around 1887. Another historian, Dr. Edward Everett Dale who was a research professor of history at the University of Oklahoma, wrote in 1946 that the town had its origins in 1886 when two brothers-in-law, W.H. Acers and H.P. Dale, built a general store in hopes of trading with the Indians and garnering business from cattle herders heading north to Kansas. At the time the men came to the area, it was actually part of Greer County, Texas.

Some historians credit Joseph S. “Buckskin Joe” Works, a Texas land promoter, with the founding of today’s ghost town around 1887. Another historian, Dr. Edward Everett Dale who was a research professor of history at the University of Oklahoma, wrote in 1946 that the town had its origins in 1886 when two brothers-in-law, W.H. Acers and H.P. Dale, built a general store in hopes of trading with the Indians and garnering business from cattle herders heading north to Kansas. At the time the men came to the area, it was actually part of Greer County, Texas.

Acers and Dale applied for the establishment of a post office under the name of “Navajo”, presumably named after the nearby Navajo Mountains. They got their post office which opened for business on September 1, 1887 under the name “Navajoe” – the extra “e” would differentiate it from the post office in Navajo, Arizona (this long before the days of postal zip codes).

A general store and a post office doesn’t necessarily a town make, but after Buckskin Joe arrived on July 4, 1887 he immediately launched efforts to formally lay out an eighty-acre town site. In return for his agreement to promote the town he was granted half of the lots. For those efforts, even though Acers and Dale had been there first, Works was considered the town’s “father”. Before the year was over a Baptist Church, the first Protestant church to be established in what would eventually become Oklahoma Indian Territory, was established. The following year the Navajoe School was opened.

On February 8, 1860, Governor Sam Houston had established Greer County, carved out of a portion of Young County, and named after John Alexander Greer, a veteran of the Texas War for Independence. The Civil War interrupted the formal establishment proceedings, however, but by July of 1886 the county had been organized with a government in place – this despite the fact that for years the United States government and the State of Texas had been embroiled in a dispute over boundaries.

On February 8, 1860, Governor Sam Houston had established Greer County, carved out of a portion of Young County, and named after John Alexander Greer, a veteran of the Texas War for Independence. The Civil War interrupted the formal establishment proceedings, however, but by July of 1886 the county had been organized with a government in place – this despite the fact that for years the United States government and the State of Texas had been embroiled in a dispute over boundaries.

A brief was submitted to the United States Supreme Court and on March 16, 1896 the Court ruled in favor of the United States government, concluding:

The territory east of the 100th meridian of longitude, west and south of the north fork of Red river, and north of a line following westward, as prescribed by the treaty of 1819 between the United States and Spain, along the south bank both of Red river and of the Prairie Down Town fork or south fork of Red river until such line meets the 100th meridian of longitude, which territory is sometimes called Greer county, constitutes no part of Texas, but is subject to the exclusive jurisdiction of the United States.

Translation: the border dispute was over whether the south fork or the north fork of the Red River was the natural boundary. Navajoe lay within the area bounded by the two forks.

Buckskin Joe had big plans for Navajoe. Upon arrival he built a home for his family, a half-dugout type which he claimed cost only thirty-five dollars to build. His next venture was a hotel for those coming to the territory in search of land. He also established a publication called “The Emigrant’s Guide” to circulate throughout Texas to attract settlers to “his” town. Despite his obvious enthusiasm in settling the area, Works remained there for only a year or two. By 1891 he was promoting the town of Comanche near Chickasaw territory.

Still, his efforts continued to pay off and others benefited from it. Acers and Dale prospered with their general store and settlers came despite the border dispute. The establishment of a post office had helped as well since before that time mail service came sporadically from Vernon, Texas. Afterwards the mail carrier rode down to the Red River and met the carrier from Vernon. The post office was located in a corner of the general store and was the meeting place every evening as the men gathered to await the posting of that day’s mail around eight o’clock. Dr. Edward Dale described the nightly ritual:

Still, his efforts continued to pay off and others benefited from it. Acers and Dale prospered with their general store and settlers came despite the border dispute. The establishment of a post office had helped as well since before that time mail service came sporadically from Vernon, Texas. Afterwards the mail carrier rode down to the Red River and met the carrier from Vernon. The post office was located in a corner of the general store and was the meeting place every evening as the men gathered to await the posting of that day’s mail around eight o’clock. Dr. Edward Dale described the nightly ritual:

Here they sat on the counter, smoked cigarettes, chewed tobacco, and told yarns or indulged in practical jokes while waiting for “the mail to be put up”. Once this was accomplished and the window opened each and every one walked up to it and solemnly inquired: “Anything for me?” Few of them ever got any mail; most of them would have been utterly astonished if they ever had got any mail but asking for it was a part of a regular ritual and missing the experience was a near tragedy.

Other business establishments followed, including another general store just north of Acers and Dale’s store – not nearly as successful as theirs, however. Ed Clark opened a saloon down the street with a room for poker, seven-up and dominoes. It was, of course, a popular place for cowboys and “the town’s loafers” as Dr. Dale called them. However, the church-going folks objected (their house of worship was across the street) and eventually voted the town dry, with the exception of certain patent medicines.

W.H.H. Cranford was the town “druggist” who sold those patent medicines especially to the local Indians because under federal laws they were not to be sold liquor (so-called patent medicines were notoriously constituted of significant amounts of alcohol). Other stores were built, some busy and some not. Most had a porch where the men could sit around and “shoot the breeze”. The town’s doctor, H.C. Redding, had his office across the street from Cranford’s establishment. Redding disliked Cranford intensely since his “medicine” often deprived the doctor of patients and a fee.

Some cattle ranchers leased Indian lands to graze their cattle and had money to pay their hands fairly well, but most settlers in the area were very poor. The occasional odd job and perhaps a small crop of wheat yielded very little income. Some would spend their winters poisoning and skinning wolves or killing prairie chickens and quail.

The general population of the area may have been impoverished but that didn’t prevent them from enjoying what life they had – “characterized by abundant leisure” as Dr. Dale put it. Merchants were seldom too busy to gossip and “chew the fat” with their customers or whoever wandered into their stores. The town had its share of colorful characters as well.

One such character was Uncle Billy Warren, described by Dr. Dale as “a small, dried up old fellow who had been a scout for the United States Army in earlier days.” Warren received a pension of thirty dollars a month, which likely made him one of the most “wealthy” men in town. A gambler known as “eat ‘em up Jake” got his nickname allegedly following a hand of cards containing five aces. His opponent, of course, had something to say about that, but Jake crumpled the fifth card and ate it to avoid a confrontation.

Interestingly, another man by the last name of Harlan lived at the hotel. He appeared to be an educated man and when he had been drinking would use legal terms and refer to himself as “Judge”. As it turns out, he was the brother of Supreme Court Justice John Marshall Harlan who would deliver the Court’s opinion regarding the border dispute. A letter from Justice Harlan had arrived addressed to the postmaster inquiring about his brother’s welfare. The postmaster promptly replied that his brother “as highly respected when sober and well cared for when drunk so it was not necessary to feel any uneasiness about him.”

Despite its relaxed atmosphere the town had its share of excitement in the way of gunfights and a nearby battle with Kiowa Indians in 1891. Acers and Dale eventually sold out and left the area. The post office was moved to Cranford’s store and he increased his inventory, adding dry goods, clothing, notions – and a stock of coffins in an attic above the store.

Following the Court’s decision in 1896 the town went through a series of changes as people moved on and others came into the area then known as Oklahoma Territory. Some of the more “colorful” characters may have departed, but after new settlers came to farm the area acquired a little more sophistication, according to Dr. Dale. In the late 1890’s a brief mining boom occurred – for years it had been speculated that the Navajo Mountains held treasures of gold.

The boom turned out to be more of a bust but another wave of settlers would come in 1901 following the opening of Kiowa-Comanche lands to white settlement. One would think that would have improved the long-term viability of the town of Navajoe. However, it effected just the opposite. Many citizens of Navajoe secured some of that land and left the town. The new settlement areas would have railroad access.

As was the case many times over during that era, towns without a nearby railroad slowly died away. Navajoe was never a big town but had plenty of character as evidenced by its array of colorful and interesting citizens. As Dr. Dale phrased it, “[I]n the full vigor of youth it simply vanished from the earth.”

The area is now situated in Jackson County, Oklahoma. The Navajoe Cemetery remains, and according to Find-A-Grave has over seven hundred interments, some very recent. Dr. Dale lived in Navajoe for a time and remembered it this way (in reference to the cemetery):

The area is now situated in Jackson County, Oklahoma. The Navajoe Cemetery remains, and according to Find-A-Grave has over seven hundred interments, some very recent. Dr. Dale lived in Navajoe for a time and remembered it this way (in reference to the cemetery):

Here lies the bodies of more than one may who died with his boots on before the blazing six gun of an opponent and others who died peacefully in bed. Here also lie all that is mortal of little children, and of the tired pioneer women who came west with their husbands seeking a home on the prairie only to find in its bosom that rest which they had so seldom known in life.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Tombstone Tuesday: Lieutenant Nathaniel Bowditch (Part Two)

Nathaniel Bowditch arrived at Hilton Head and discovered the temperature to be 120 degrees in the shade! NOTE: If you missed Part One of this story, you can read it here. His regiment was ordered to Aquia Creek on August 25 and he was resigned to the inevitability that they would be engaged in battle. He asked his family to “not feel anxious if you do not hear from me for several days. I go forward with perfect confidence in my heavenly Father, and know that whatever he does is for the best.”

The regiment did indeed engage the enemy and on September 7 they lost thirty men (some taken prisoner). They were on the move constantly that month, although they missed the bloody engagement at Antietam. What Nathaniel didn’t mention to his family was that in truth his regiment was not doing well at all, primarily due to the condition of their horses, but in general morale was especially low as well.

Nevertheless, he had plenty to do and occasionally engaged the enemy. Late in September he was dispatched as a scout with a team of eight men. They came upon the enemy, numbering perhaps seventy-five to one hundred and decided to retreat. Even in retreat Nathaniel still lost three men, and was later upbraided by his commanding officer for not firing at the enemy. From that point he vowed to never let that happen again: “If I ever get another chance, no man shall accuse me of not doing my whole duty. I will do so, even if I fall in the attempt.”

October of 1862 began with a policing action involving Union soldiers who were drunk and disorderly and later court-martialed. It was not a pleasant task confronting his fellow soldiers. “This is the first time I have ever had any thing of the kind happen to me, and I hope it will be the last.” Meanwhile, conditions were worsening for the troops – rain, wind and inadequate covering made for a miserable existence. The horses continued to struggle and there had been no pay for over four months. To his family: “You will excuse me if have said any thing I ought not – I am alive and well.”

October of 1862 began with a policing action involving Union soldiers who were drunk and disorderly and later court-martialed. It was not a pleasant task confronting his fellow soldiers. “This is the first time I have ever had any thing of the kind happen to me, and I hope it will be the last.” Meanwhile, conditions were worsening for the troops – rain, wind and inadequate covering made for a miserable existence. The horses continued to struggle and there had been no pay for over four months. To his family: “You will excuse me if have said any thing I ought not – I am alive and well.”

On October 30, Nathaniel was promoted to first lieutenant and by November 3 the regiment had arrived at Hagerstown, “penniless with their rags and tags”. By the end of the month his regiment had arrived at their winter headquarters near Falmouth, Virginia. Upon inspection, his regiment gained the approval of the commanding General for appearance and discipline.

In recognition of his skills and leadership, Nathaniel was promoted to Adjutant of his regiment on December 1, 1862. Although grateful for the appointment, he found some of his duties “irksome” enough to consider resigning. His family, as always, encouraged him to remain in his new position. His mother made remarks that proved to be the deciding factor: “There’s no such word as fail . . . ‘what man has done, man can do,’ is another homely phrase, but a good one to think of.”

Nearing the end of January, 1863 Nathaniel had received orders from General Burnside that his regiment would be advancing to Fredericksburg. He realized the mission would be dangerous, and in a letter to his mother, prepares his family for the possibility they may never see him again:

My Darling Mother,

To-morrow morning we leave, and shall probably have some hard work; for we are going to cross the river. I have just received an order from General Burnside, which certainly looks like it. I will give you a copy of it . . . I send this order that you may see what is expected of us. This may be the last letter you will receive from me. If so, you must know that I have always tried to do my duty to the best of my ability, although it has been at times hard work to please everybody. . . I must now bid you good-by, with love to all my friends and relations.

In early February his regiment was sent on an expedition to destroy a bridge over the Rappahannock River, undertaken in harsh weather – “It was one of the hardest times we have ever had.” February continued to bring even harsher weather and by the 22nd (Washington’s birthday) he was writing about the “ignoramuses of the North demanding an onward movement while the snow is a foot and half deep.”

On February 26, Nathaniel informed his family of his promotion to serve Colonel Duffié as his Aide-de-camp, as well as the position of Acting Assistant Adjutant-General of the entire brigade. He was keenly aware of the challenges ahead.

Around March 5, in a letter to his mother, Nathaniel wrote of his contentment and happiness with his new job and pleased to be working with Duffié, whom he called “a very pleasant man.” In approximately ten days he was hoping to receive a furlough and be able to see his family. On March 12, he wrote that he was very happy with his new post, working until midnight some nights and up again early the next morning. “This gives you an idea of what my life is – at work from morning till night; but, for all that, I like it, and don’t think I ever felt happier in my life.”

On March 15, 1863 Nathaniel wrote what would be his last letter to his family. He alluded to leaving the next morning with “eleven hundred and sixty-six men, on some sort of a raid; but I don’t know, as yet, where. We are to be gone four days or so; and then I shall, in all probability, be on my way home; so that you must not be surprised if I pop in on you any night towards the end of the week, or the first of next.”

His “surprise visit” never happened, at least not as he envisioned. As his father Henry wrote, “He said the truth. ‘On the first day of the next week,’ his dear but dead body was resting again under his parents’ roof.” After returning from a bridal party of one of Nathaniel’s closest friends, Henry received a telegram, dated March 18, 1863 at Potomac Creek: “Nat shot in jaw; wound in abdomen; dangerous. Come at once.”

Henry rushed toward Washington, D.C., but Nathaniel had already died by the time he arrived. Nathaniel’s brigade had been dispatched to Kelly’s Ford, a crossing on the Rappahannock River. They had been ordered to cross it and, if possible, attack and cut off Generals Jeb Stuart and Fitzhugh Lee’s cavalry.

About 4:00 a.m. on Tuesday, March 17, most of the brigade headed out and later engaged the enemy that day. Many horses were shot and killed and several soldiers wounded. Colonel Duffié’s horse threw him into the river. Adjutant Bowditch, however, escaped unharmed in that day’s first engagement. Later in the day parts of the brigade again faced the enemy’s cavalry – the rebels “yelling like demons, and apparently confident of victory.”

The First Rhode Island surged ahead and met the enemy head-on causing them to flee. So excited were they to have routed the enemy and taken several prisoners, however, they didn’t notice another wave of rebel forces charging upon them. Eighteen Union soldiers were captured and, unfortunately, Lieutenant Nathaniel Bowditch was wounded after killing three rebels.

Apparently he had charged ahead into the enemy’s ranks, well ahead of the command he was leading and found out too late than he had no support. Upon discovering his dilemma he had attempted to turn back, but instead received a sabre blow to the head and was shot in the shoulder.

Henry, before publishing his memoir, had asked an officer who witnessed the battle scene whether his son had acted in a rash or un-military manner – did he perhaps throw his life away? The officer did not hesitate to state, “What he did, he did exactly in the line of duty, not rashly or carelessly. It was his place to lead; and he did so, most bravely, even to the sacrifice of his life.”

After being thrown from his horse, Nathaniel lay helpless and was fired upon several times – one man threatened to blow his brains out. He was shot in the abdomen and the attending surgeon later determined this was probably the fatal shot. Nathaniel continued to lay on the ground until he determined for certain the identity of a fellow soldier who was passing by. He asked for assistance and was lifted onto a horse, leaning over its neck as they proceeded out of the field.

Along the way two surgeons had seen him and believed him to be mortally wounded, to which Nathaniel replied, “Well, I hope I have done my duty; I am content.” One of the surgeons had asked having done his earthly duty was he ready for the next. The surgeon asked if he believed in Christ and had assurance of his sins being forgiven. Nathaniel answered in the affirmative.

Still, Lieutenant Bowditch lingered, suffering great pain, and two ambulance rides only added to his suffering. Around 11:00 p.m. on March 18 the attending doctors believed he was slipping away. Dr. Holland “gently drew up his arms, crossed them upon his manly breast, and spoke kindly to him.” He later fell gently asleep at the age of “twenty-three years, three months, and twelve days.”

His funeral service was held in the family home on March 25, led by Reverends C.F. Barnard and James Freeman Clarke. Reverend Clarke delivered words of comfort to those assembled and in his concluding remarks declared:

He was filled with an inward peace which, I believe, came direct from God. We do not now see the angels which come to strengthen us in such hours; but they are surely there. Such strength and peace only comes from the higher world. He did not look back regretfully; he was lifted above anxiety, above those he loved. He had no fear of the future; it was all well with him. It is all well with him.

His flag-draped coffin was transported to Emanuel Church where some of his fellow officers waited to bear his body to its temporary resting place inside the family vault. Lieutenant Nathaniel Bowditch was later permanently interred beside his grandparents Nathaniel and Mary Bowditch (see last week’s Surname Saturday article for more on Nathaniel the elder here).

Interestingly, following Nathaniel’s death and the battle at Kelly’s Ford, public opinion in the North changed in regards to their army’s ability to engage the enemy, especially as cavalrymen. As Henry Ingersoll Bowditch saw it:

Previous to that period, there had been a general feeling that the South was better able than the North to raise a cavalry force. Men in the South, owing perhaps as much to the want of good roads in that part of the country as to any other cause, had passed much of their time in the saddle. They were, moreover, in their own estimation at least, the only lineal descendants of the old Cavaliers. Northern men, on the contrary, born under the genial influences of freedom, and where good roads lead to every hamlet, had resorted to the less manly, but more luxurious, mode of traveling in carriages.

In both the press and the court of public opinion, a hopefulness arose in the North. Even though the battle at Kelly’s Ford was small in comparison to the other greater and bloodier battles of the Civil War, this one seemed to have raised the morale of the entire Union Army. Apparently, Lieutenant Nathaniel Bowditch did not die in vain after all.

Source: Memorial of Nathaniel Bowditch, by Henry Ingersoll Bowditch, 1865.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

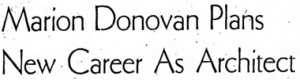

Mothers of Invention: Marion Donovan (Disposable Diapers)

Parents around the world can thank today’s “mother of invention” every time they pick up a Pampers®, Huggies® or Luvs® to change their little one’s diaper. Although her ideas were considered impractical at the time, they eventually led to the first truly disposable diaper coming to market in 1961.

Parents around the world can thank today’s “mother of invention” every time they pick up a Pampers®, Huggies® or Luvs® to change their little one’s diaper. Although her ideas were considered impractical at the time, they eventually led to the first truly disposable diaper coming to market in 1961.

Marion O’Brien Donovan was born October 15, 1917 to parents Miles and Ann (O’Connor) O’Brien in Fort Wayne, Indiana. Her career later as an inventor must have come naturally since she was born into a family of inventors. Her father and uncle John (they were twins) ran a manufacturing plant in South Bend and had invented an industrial lathe which ground automotive gears and gun barrels.

Apparently, her father, the son of Irish immigrants, was quite successful at his trade – in the 1920 and 1930 censuses the family employed two servants. Ann O’Brien, however, had died in 1925, leaving Miles with two daughters to raise – Frances and Marion. Marion spent quite a bit of time during her childhood observing operations at her father’s business, perhaps because her mother had died. Miles helped Marion with her first childhood invention – tooth powder (she would later invent a new type of dental floss).

Apparently, her father, the son of Irish immigrants, was quite successful at his trade – in the 1920 and 1930 censuses the family employed two servants. Ann O’Brien, however, had died in 1925, leaving Miles with two daughters to raise – Frances and Marion. Marion spent quite a bit of time during her childhood observing operations at her father’s business, perhaps because her mother had died. Miles helped Marion with her first childhood invention – tooth powder (she would later invent a new type of dental floss).

In 1939 Marion earned a Bachelor’s Degree in English from Pennsylvania’s Rosemont College and afterwards worked briefly for Vogue magazine as an assistant beauty editor. In 1942 she married James F. Donovan and together they had three children: Christine, Sharon and James.

For years, several individuals had attempted to invent and market a disposable diaper. Robinsons and Sons of Chesterfield (England) had marketed wholesale “Destroyable Babies Napkins” in the 1930’s to hospitals, but apparently didn’t envision a market for the general public. In 1946 a Swedish company suggested the use of cellulose “wadding” inside a cloth diaper covered with rubber pants. That didn’t work very well as the wadding tended to crumble when moist and also caused skin discomfort.

In 1946 Marion crafted her own version of rubber pants out of shower curtain, using her own sewing machine. As Dr. Andrew Boyd, a faculty member in the Industrial Engineering Department at the University of Houston, put it: “motherhood proved to be the necessity of invention.” The rubber pants on the market at the time had drawbacks because they also caused skin discomfort and diaper rash. Hers were crafted to avoid discomfort and replaced pins with snaps. Because her invention looked like a boat, she called them “Boaters”.

In 1946 Marion crafted her own version of rubber pants out of shower curtain, using her own sewing machine. As Dr. Andrew Boyd, a faculty member in the Industrial Engineering Department at the University of Houston, put it: “motherhood proved to be the necessity of invention.” The rubber pants on the market at the time had drawbacks because they also caused skin discomfort and diaper rash. Hers were crafted to avoid discomfort and replaced pins with snaps. Because her invention looked like a boat, she called them “Boaters”.

Undeterred by manufacturers who had no interest in her invention, she conducted her own marketing campaign and successfully placed her product in Saks Fifth Avenue in 1949. In 1951 she received a patent and sold the rights to the Keko Corporation, a clothing manufacturer, for one million dollars. However, her efforts to invent a truly disposable diaper continued.

The diaper had to be made of a fully absorbent and strong paper that would repel moisture away from the baby’s skin. After perfecting her invention she again set out to present her idea to manufacturers, only to be rebuffed yet again for her “impractical idea”. However, in the 1950’s companies like Johnson & Johnson, Playtex and others were looking to develop such a product of their own. In 1961, Proctor & Gamble brought disposable diapers, marketed as Pampers®, after being perfected by a team headed by Victor Mills.

Marion continued to invent, receiving twenty patents between 1951 and 1996 for such products as dental hygiene products, hosiery clamp, combined envelope and writing sheet, and others which were geared to women as a matter of convenience. The DentaLoop, which eliminated the need to wrap floss around one’s fingers to use, was invented in 1985.

In one 1950’s article about housewives who had struck it rich, Marion’s accomplishments were downplayed, claiming she had no knowledge of science and any mechanism more complex than an egg beater would be baffling to her. Her life experience and education, however, stood in direct contradiction to that insulting insinuation.

In the mid- to late-1950’s she pursued an architecture degree at Yale University, graduating in 1958 as one of three women in her class that year. Her hometown newspaper lauded her accomplishments with the following headline:

The Bridgeport Post reported:

Determination plus talent multiplied by hard work equals realization of one’s dream. That seems to be the living equation worked out and practiced by Mrs. James F. Donovan of Harbor Road, Southport. A busy wife and mother and a successful designer for many years, Mrs. Donovan received her bachelor’s degree in architecture from Yale University this month and hopes to launch a career in that field soon.

She was described as a “tall, slim woman with classic Gaelic beauty”, succeeding “in more fields than most women would dream of attempting.” Indeed, she was always interested in educating herself and pursuing lofty goals of success. Her daughter remembered Marion setting up a reel-to-reel tape recorder in her car so she could learn French and dictate letters during her commutes back and forth to Yale.

Marion and James divorced in 1971 and she later married John Butler. In 1981 she designed her own home in Greenwich, Connecticut, later revealing in a 1994 interview that she had always been fascinated by structure. She continued to market her products, including DentaLoop, to retailers. But by 1995 she was ready to sell the rights to DentaLoop after her husband suffered a stroke in 1995.

John died in July of 1998 and Marion died four months later on November 4, 1998. Her daughter Christine later recalled her mother’s work ethic: “One thing that was fantastic about her: running into an obstacle made her approach the idea in a new way. Her philosophy was keep thinking and working to improve.”

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Surname Saturday: Bowditch

Bowditch

This unique surname is of Anglo-Saxon origin, believed to have derived from an estate in Dorsetshire (pre-Norman Conquest of 1066) and seen as well in the southern counties of Somerset and Devonshire. The place name in Devon was derived from an Olde English term “bupar dice” which meant “above the ditch”. Other locational derivations such as “boga (bow) dic (ditch)” would indicate a bow-shaped water channel, according to The Internet Surname Database. Spelling variations include Bowditch, Bowdiche, Bowdich, Bowdidge, Bowdyche and more.

In 1185 someone named “Bowditch” (no surname) was recorded in County Dorset. Eighty-eight years later in 1273, William Bowditch appeared in County Dorset records. Edwin Boditch appeared in records during the reign of Edward III and Richard Bowdiche was listed in the Yorkshire Poll Tax of 1379. Two marriage records: Richard Bowdyche and Joanna Savage married in London in 1554; Thomas Bowditch and Hannah Fowler: St. George, Hanover Square in 1769.

In 1185 someone named “Bowditch” (no surname) was recorded in County Dorset. Eighty-eight years later in 1273, William Bowditch appeared in County Dorset records. Edwin Boditch appeared in records during the reign of Edward III and Richard Bowdiche was listed in the Yorkshire Poll Tax of 1379. Two marriage records: Richard Bowdyche and Joanna Savage married in London in 1554; Thomas Bowditch and Hannah Fowler: St. George, Hanover Square in 1769.

The Bowditch surname was prominent in New England and many of those bearing it could be traced back to Thorncombe, a village in Dorset. Two men of that line were well-known in their fields of mathematics and medicine, Nathaniel Bowditch and his son Henry Ingersoll Bowditch, also a prominent abolitionist.

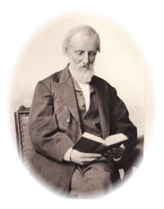

Nathaniel Bowditch

Nathaniel Bowditch was born on March 26, 1773 in Salem, Massachusetts to parents Habakkuk and Mary (Ingersoll) Bowditch, the fourth of seven children. At the age of ten, Nathaniel’s childhood abruptly ended when he was removed from school to work in his father’s cooperage (barrel maker). Two years later Nathaniel was apprenticed as a bookkeeper to a ship chandler for nine years.

Even though his education had been interrupted due to pressing family financial circumstances, Nathaniel began to undertake his own self-education at the age of fourteen by studying algebra, calculus, astronomy, Latin and French. When his apprenticeship ended he began making voyages to the East Indies as a ship’s clerk. During his free time on those voyages he pored over the navigational tables of John Hamilton Moore, a well-known English navigator. Astonishingly, Nathaniel discovered and corrected over eight thousand errors in Moore’s work, The Practical Navigator.

In 1802 Nathaniel published The New American Practical Navigator in both America and England, reflecting the corrected tables. The book, nearly six hundred pages in length, also contained information on navigational laws and terminology. It was said to have been written in a format easily understood, even by uneducated sailors. It would become an essential part of every seaman’s gear. In recognition of his work, Harvard University awarded this self-educated man with an honorary Masters of Arts degree in 1802 (and later a Doctorate).

In 1802 Nathaniel published The New American Practical Navigator in both America and England, reflecting the corrected tables. The book, nearly six hundred pages in length, also contained information on navigational laws and terminology. It was said to have been written in a format easily understood, even by uneducated sailors. It would become an essential part of every seaman’s gear. In recognition of his work, Harvard University awarded this self-educated man with an honorary Masters of Arts degree in 1802 (and later a Doctorate).

In 1798 he had married Elizabeth Boardman, but she died seven months after their wedding. In 1800 he married Mary (Polly) Ingersoll Bowditch, his cousin. His mathematical skills led him to become the nation’s first insurance actuary as president of Essex Fire and Marine Insurance Company in 1804, and he successfully led the company through a difficult period of time which encompassed the War of 1812 and its aftermath. In 1823 he and his family moved to Boston where he worked for Massachusetts Hospital Life Insurance Company until 1838 – at five times the salary he received at Essex as its president.

Throughout his career in the insurance industry Nathaniel continued to work in the fields of mathematics and science, publishing several books and papers. His work was recognized widely and he was inducted into several foreign academies, including the Royal Societies of Edinburgh and London. Nathaniel Bowditch died on March 16, 1838 of stomach cancer and was buried in Mount Auburn Cemetery. Through public donations, a statue was later erected in his honor.

Henry Ingersoll Bowditch

Henry Ingersoll Bowditch was born on August 9, 1808 in Salem to Nathaniel and Mary Bowditch. His mother was described as “a woman of great piety without a trace of sanctimoniousness” (Life and Correspondence of Henry Ingersoll Bowditch, Vol. I, p. 2) and his upbringing instilled in him a deep religious faith.

Henry, the son of a self-educated scholar, received a well-rounded education. After the family moved to Boston, Henry entered the Public Latin School and in 1825 entered Harvard as a sophomore at the age of seventeen, eventually entering Harvard’s medical school. In 1832, Nathaniel sent his son abroad to Europe to continue his medical education. There he studied and came to be influenced by the teachings of William Wilberforce, renowned abolitionist.

Upon his return to America in 1834, he witnessed the attempted lynching of William Lloyd Garrison, an American abolitionist. Thereafter, Henry officially counted himself as one as well, vowing to devote “his whole heart to the abolition of that monster slavery”. On July 17, 1838 he married Olivia Yardley whom he had met while abroad.

For several years leading up to the Civil War he remained active in the abolitionist movement, even making the acquaintance of Fredrick Douglass. He especially targeted the slave-hunters who frequented Boston looking for runaway slaves, helping to organize the Anti-Man-Hunting League. Members were trained to capture and detain slave-hunters in exchange for a runaway slave’s freedom.

For several years leading up to the Civil War he remained active in the abolitionist movement, even making the acquaintance of Fredrick Douglass. He especially targeted the slave-hunters who frequented Boston looking for runaway slaves, helping to organize the Anti-Man-Hunting League. Members were trained to capture and detain slave-hunters in exchange for a runaway slave’s freedom.

When the Civil War began, his son Nathaniel, who was set to follow Henry in the field of medicine, considered joining the Second Massachusetts Regiment but an injury prevented that. However, when one of his former classmates was killed at Ball’s Bluff in Loudoun County, Virginia, Nathaniel announced his intentions: “I have decided to go, because I have made up my mind that it is my duty to do so.”

Tragically, Nathaniel was killed at Kelly’s Ford in Virginia which spurred Henry to write a pamphlet advocating a battlefield ambulance system to better care for the wounded. Later he wrote a memoir to honor Nathaniel. In case you missed it, this week’s Tombstone Tuesday article featured Part One of a two-part article on Nathaniel Bowditch – you can read it here.

Henry founded the Massachusetts State Board of Health in 1869 and served as its first chairman, and served as president of the American Medical Association in 1877. He was a professor at Harvard Medical School and continued practicing at Massachusetts General Hospital until his death on January 14, 1892.

Other prominent members of this family include Henry Pickering Bowditch (physician, dean of Harvard Medical School), Charles Pickering Bowditch (archaeologist and Henry’s brother) and more.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Ghost Town Wednesday: Ghost Towns of Sherman County, Kansas

This county in northwestern Kansas had been home to buffalo-hunting Native Americans and was named for General William Tecumseh Sherman of Civil War fame by the Kansas legislature in 1873. Cattle and sheep ranches were established in the early 1880’s on land available for little or no cost.

This county in northwestern Kansas had been home to buffalo-hunting Native Americans and was named for General William Tecumseh Sherman of Civil War fame by the Kansas legislature in 1873. Cattle and sheep ranches were established in the early 1880’s on land available for little or no cost.

A few towns had already been founded in 1885 and early 1886 as settlers made their way to the area, including a fair number of foreign immigrants from Sweden, Germany and Austria: Eustis, Sherman Center, Voltaire, Itasca and Gandy. On September 20, 1886 the county was officially organized and Eustis was named the temporary county seat. Other towns established in 1887 and 1888 were Goodland, Ruleton and Kanorado (near the Colorado state line, thus the hybrid name). Here is a brief history of those which quickly became ghost towns.

Eustis

In the spring of 1885, P.S. Eustis and O.R Phillips organized the Lincoln Land Company and laid out the town. P.S., as an agent of the Burlington & Missouri River Railroad, had the distinction of having the town named in his honor. In July of 1886 a post office was opened.

After being named the temporary county seat in September, an election was held on November 8 to allow voters to decide which town, Sherman Center or Eustis, would be the permanent county seat. Eustis won and construction began on a courthouse. The following spring another election was held and Eustis came out victorious.

For reasons unclear, another election was called for in August of 1887 by a county committee to once and for all determine the county seat. Representatives of Voltaire and Sherman Center and someone named B. Taylor who owned land in the central part of the county made their pitches before the committee. Eustis declined to make a presentation. At the next meeting of the county committee, representatives of newly-established Goodland made a well-received presentation.

Of the almost fifteen hundred votes cast in the fall election, Goodland won 872 of those votes. The official vote tallies could not be completed, however, after injunctions were filed which prevented county commissioners from canvassing the vote. Therefore, between November 1887 and January 1888 the county seat issue remained unsettled with court battles and more commission meetings.

Of the almost fifteen hundred votes cast in the fall election, Goodland won 872 of those votes. The official vote tallies could not be completed, however, after injunctions were filed which prevented county commissioners from canvassing the vote. Therefore, between November 1887 and January 1888 the county seat issue remained unsettled with court battles and more commission meetings.

On January 13, 1888 the matter began to reach a boiling point when a group from Goodland marched to Eustis intending to seize the county records. A war of words ensued in newspapers throughout the county. The rivalry heated up to the extent that Governor John Martin sent the Kansas National Guard to monitor the situation. However, by early May, Eustis had withdrawn its objections after Goodland had hired a posse of sorts which captured one of the county commissioners and forced him to allow the county records to be removed – no shots fired, end of dispute.

Not long afterwards, the citizens of Eustis began to move to the new county seat, eventually leading to the town’s demise. For the same reasons, the town of Sherman Center also faded away.

Gandy

The town of Gandy had been founded in June of 1885, named after Dr. J.L. Gandy of Humboldt, Nebraska. Its post office was established in September and the first county newspaper, “The New Tecumseh” published its first issue on November 11, 1885. The first school in the county was also established in Gandy.

Gandy seemed to be taking root with these county “firsts”, but by early 1886 had begun to decline. In March the newspaper moved to Itasca and later that fall the post office was moved to Sherman Center, established in May of 1886. Itasca would eventually suffer the same fate as Sherman Center and Gandy. Like a row of dominoes, these fledgling communities continued to fall.

Voltaire

This town was founded by a group from Rawlins County, Kansas on June 15, 1885 and named for French philosopher Voltaire. By the summer of 1886 the town reached its peak with just over one hundred and forty residents and forty-five buildings and homes. As was the case in countless “county wars”, Voltaire began to decline after an unsuccessful bid to become the seat of government for Sherman County.

Voltaire had been established on government land, and therefore was required to maintain a certain population level until the land could be officially turned over to the town. With winter on its way following the election defeat, few residents wanted to remain in Voltaire, but the town’s founders hired a man and his family to remain there to hold the town until spring when more settlers would arrive and improvements could be made.

Those who left returned to Rawlins County (Atwood) for the winter, one which proved to be an especially harsh and deadly one. Instead of returning, residents decided to remain in Atwood and Voltaire began to decline. In 1889 the post office was closed and the town vacated by the Kansas legislature.

Today the towns of Goodland (still the county seat) and Kanorado remain; Ruleton is a small unincorporated community.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Tombstone Tuesday: Lieutenant Nathaniel Bowditch (Part One)

Nathaniel Bowditch (pronounced bau-ditch) was born to parents Dr. Henry Ingersoll and Olivia Jane Yardley Bowditch on December 6, 1839. As noted in the memoir written by his father, Memorial of Nathaniel Bowditch, he “received his grandsire’s name because he was the first grandson born.” His grandfather was a renowned early American mathematician who specialized in maritime navigation. More on Nathaniel the grandfather in this week’s Surname Saturday article.

Nathaniel, a well-behaved child, began school between the ages of four and five. His teacher remembered his “pleasant deportment, his affectionate disposition, his thoughtfulness of the comfort of others, his obedience, and his gentleness.” At one point, however, his mother thought his gentle spirit would prevent him from being able to defend himself later in life – after one incident he had run to his mother and said, “I hate to fight.”

Following his early schooling, Nathaniel entered Dr. Charles Kraitsir’s school in Boston which emphasized the structure and historical development of language. After two years there he entered public grammar school, followed by a private school and then spent six years under an uncle’s tutelage. By that time, Nathaniel’s father was ready for him to continue his educational pursuits at the Lawrence Scientific School, founded by Albert Lawrence and the precursor to Harvard’s School of Engineering and Applied Sciences.

In September of 1858 he entered the school for a three-year course of study. Henry believed it would prepare his son for a career in medicine, and Nathaniel diligently studied — in the words of his father, “with an intense love of his work, Nat devoted himself, day after day, to learn thoroughly everything that could be acquired concerning the structure of the class of the animal kingdom, to which he was devoting himself.”

He spent hours studying zoology and performing minute dissections, something that would be useful should be become a surgeon. His father reflected on his skills later, believing that, although it might have seemed absurd to some, Nathaniel “actually wielded the sabre on the fatal field of Kelley’s Ford in a more effective manner, in consequence of the hours and days of quiet labor passed at the feet of the great naturalist.”

He spent hours studying zoology and performing minute dissections, something that would be useful should be become a surgeon. His father reflected on his skills later, believing that, although it might have seemed absurd to some, Nathaniel “actually wielded the sabre on the fatal field of Kelley’s Ford in a more effective manner, in consequence of the hours and days of quiet labor passed at the feet of the great naturalist.”

In September of 1861 Nathaniel formally entered the study of medicine, intending to devote an entire year to the study of human anatomy and physiology. In addition to his studies, he began following Henry’s medical cases and visiting Massachusetts General Hospital on Saturdays to observe surgeries. Henry, of course, swelled with pride at his son’s accomplishments and none more so than the observation that “a deep religious feeling had been for months stealing over him, and high principle seemed to be his guiding star.”

After Fort Sumter’s fall in April of 1861, Nathaniel had considered joining the cause but an accident prevented him from joining the Second Massachusetts Regiment. His parents were, understandably, relieved since although proud of his patriotism were not eager for him to “offer himself as a champion, and possible as a martyr, to the cause.”

Everything would change, however, about two months after he entered medical school. On October 22, 1861 devastating news came of the carnage at Ball’s Bluff, a humiliating defeat for the Union in Loudoun County, Virginia. Lieutenant William Lowell Putnam, a former classmate of Nathaniel’s, died in that battle, his death affecting Nathaniel profoundly. “Nat felt that the die was cast, that his own hour had come.” He calmly and assuredly announced his intentions to his family: “I have decided to go, because I have made up my mind that it is my duty to do so.”

On November 5, 1861 Nathaniel Bowditch was commissioned as a Second Lieutenant of the First Regiment of Massachusetts Volunteer Cavalry by Governor John Albion Andrew. He immediately reported for duty at Camp Meigs under the command of Colonel Robert Williams. His transition to army life, however, was not a smooth one.

Just before he arrived at the camp, incidents of insubordination had resulted in violence in order to subdue it. Upon his arrival, Nathaniel was ordered to return to Boston and await further orders until order was restored. Nathaniel, as his father noted, was a lover of peace and one reluctant to resort to force. The incident affected him to the point that upon his return home he told Henry he wasn’t fit for the task – “I can never govern men, if it be necessary to do what is now done at camp. I must resign my commission.”

It must have pained him to do so, but Henry encouraged him to stick it out: “My boy, be of good cheer; you are new in this business. All things will be well, I have no doubt. You know, however, that it is not the custom for any of us to give up an important object, until we have either gained it, or have become convinced that we are unable to gain it. Then, and not till then, do we resign. . . go ahead, trusting in the Lord.”

This encouraged Nathaniel, and instead of brooding, he spent his time honing his sword and horsemanship skills. On Christmas Day he received urgent orders to return to the camp and on December 28, left Camp Meigs for New York with his regiment. Two weeks later they embarked on a rough voyage to Port Royal, South Carolina, arriving on January 17, 1862.

Nathaniel and his family began their correspondence – Nathaniel’s letters were about camp life, friendships, and both the mundane tasks and the hard times. His family had determined that it was their duty to encourage and support him and to “make light of hardship and annoyances.” They would regularly send him quotes from various authors and news clippings, which he carried with him until his death.

On February 17, Henry received word that Nathaniel had fallen ill on Hilton Head and went to visit his son. Henry was tempted to ask for a furlough or even his resignation, but Nathaniel eventually recovered and returned to full duty on May 1. On April 28, he had written his sister about the next campaign and expressed a decided resignation as to his possible fate: