Far-Out Friday: Memento Mori (It Was A Victorian Thing)

Today it sounds kinda creepy, but post-mortem pictures were not uncommon, especially during the Victorian era. I’m not talking about taking pictures of the dearly departed in their casket – that is practiced even today as a way to have closure when a loved one passes. The term used for the practice is “memento mori”, which in Latin means “remember death.”

Today it sounds kinda creepy, but post-mortem pictures were not uncommon, especially during the Victorian era. I’m not talking about taking pictures of the dearly departed in their casket – that is practiced even today as a way to have closure when a loved one passes. The term used for the practice is “memento mori”, which in Latin means “remember death.”

This article has been removed from the web site. It will, however, be updated and published in the September-October 2019 issue of Digging History Magazine. The article will include pictures, complete with footnotes and sources.

This article has been removed from the web site. It will, however, be updated and published in the September-October 2019 issue of Digging History Magazine. The article will include pictures, complete with footnotes and sources.

I invite you to check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? That’s easy if you have a minute or two. Here are the options (choose one):

- Scroll up to the upper right-hand corner of this page, provide your email to subscribe to the blog and a free issue will soon be on its way to your inbox.

- A free article index of issues is available in the magazine store, providing a brief synopsis of every article published in 2018. Note: You will have to create an account to obtain the free index (don’t worry — it’s easy!).

- Contact me directly and request either a free issue and/or the free article index. Happy to provide!

Thanks for stopping by!

Ghost Town Wednesday: Cayuga, Oklahoma

Today it’s still considered a census-populated area but there’s not much left of the original town site. Mathias established successful businesses and made some shrewd land deals while a resident of Kansas, a place he migrated to after being removed from the Sandusky, Ohio area with a large group of Wyandot Indians in 1843.

Today it’s still considered a census-populated area but there’s not much left of the original town site. Mathias established successful businesses and made some shrewd land deals while a resident of Kansas, a place he migrated to after being removed from the Sandusky, Ohio area with a large group of Wyandot Indians in 1843.

This article is no longer available for free at this site. It was re-written and enhanced, complete with sources and has been published in the September 2018 issue of Digging History Magazine. This particular issue features several stories related to Oklahoma history, including the state’s radical past. Other articles include: “When Red Meant Radical: Oklahoma’s Red Dirt Socialism”, “Give Me That Old Time Socialism”, “Dying (or Lying) to Get on the Dawes Rolls (or how my ancestors were Indians one minute and the next, not so much)”, and more. Should you prefer to purchase the article only, contact me for more information.

This article is no longer available for free at this site. It was re-written and enhanced, complete with sources and has been published in the September 2018 issue of Digging History Magazine. This particular issue features several stories related to Oklahoma history, including the state’s radical past. Other articles include: “When Red Meant Radical: Oklahoma’s Red Dirt Socialism”, “Give Me That Old Time Socialism”, “Dying (or Lying) to Get on the Dawes Rolls (or how my ancestors were Indians one minute and the next, not so much)”, and more. Should you prefer to purchase the article only, contact me for more information.

I invite you to check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Tombstone Tuesday: Mathias Splitlog

The subject of today’s Tombstone Tuesday article has been referred to as the “millionaire Indian”. By all accounts, like the 1980’s Smith-Barney advertisement, he “made money the old-fashion way” – he earned it. His story is widely available, but this article is a summary highlighting his life and accomplishments in honor of November being National Native American Heritage Month.

The subject of today’s Tombstone Tuesday article has been referred to as the “millionaire Indian”. By all accounts, like the 1980’s Smith-Barney advertisement, he “made money the old-fashion way” – he earned it. His story is widely available, but this article is a summary highlighting his life and accomplishments in honor of November being National Native American Heritage Month.

Most family historians believe that Mathias Splitlog was born in 1812, although exactly where he was born is unclear. Some believe he was born in Ontario, Canada and was one-half Cayuga Indian and one-half French, while others believe he was born in New York. One source indicates that some believe he might have been stolen by Indians and reared by Wyandot Indians in Ohio.

Most family historians believe that Mathias Splitlog was born in 1812, although exactly where he was born is unclear. Some believe he was born in Ontario, Canada and was one-half Cayuga Indian and one-half French, while others believe he was born in New York. One source indicates that some believe he might have been stolen by Indians and reared by Wyandot Indians in Ohio.

This article was enhanced, complete with sources, and featured in the September 2018 issue of Digging History Magazine, an issue featuring the great state of Oklahoma. Should you prefer to purchase the article only, contact me for more information.

I invite you to check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

I invite you to check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Military History Monday: Native American Code Talkers of World War I

November is the month we celebrate Veterans Day and it’s also National Native American Heritage Month. In honor of those designations and Military History Monday, today’s article will honor the Native American code talkers of World War I.

November is the month we celebrate Veterans Day and it’s also National Native American Heritage Month. In honor of those designations and Military History Monday, today’s article will honor the Native American code talkers of World War I.

The first thing to be noted is these Native American soldiers were not officially United States citizens at the time, nor were they allowed to vote, yet they served honorably and with distinction. According to research conducted by the Smithsonian Museum of the American Indian, over twelve thousand Native Americans, representing about one-fourth of the entire male population of American Indians at that time, were serving their country during World War I.

The first thing to be noted is these Native American soldiers were not officially United States citizens at the time, nor were they allowed to vote, yet they served honorably and with distinction. According to research conducted by the Smithsonian Museum of the American Indian, over twelve thousand Native Americans, representing about one-fourth of the entire male population of American Indians at that time, were serving their country during World War I.

The United States reluctantly entered the war in April of 1917. Throughout the war, the Germans had been able to break radio codes being transmitted from the other side. With secret codes being broken, runners between companies were used, but that didn’t work very well either because they were subject to German capture.

Choctaw Code Talkers

According to Bishinik, the official publication of The Choctaw Nation, near the end of the war a group of Oklahoma Choctaws serving in the 141st and 142nd Infantry were called upon to help the American Expeditionary Force win several battles in the Mousse-Argonne campaign. One day a captain walking around the camp overheard Solomon Lewis and Mitchell Bobb talking in their native language.

He took Corporal Lewis aside and asked how many more Choctaw were serving in their battalion. Lewis and Bobb were asked to send a message in their native language to Ben Carterby, another Choctaw soldier stationed at headquarters. Upon receiving the message, Carterby translated it and delivered it in English to the commander – a successful secret transmission, undecipherable by the enemy.

Just hours later, eight men fluent in the Choctaw language were shifted around so that at least one of them was stationed in each field company headquarters. Messages were also written in Choctaw and delivered by runners between the companies. The strategy worked and within twenty-four hours the tide had turned in favor of American forces. The new American code had accomplished its goal – confound and confuse the Germans.

After their initial success, another eleven Choctaw Code talkers were pressed into service. The list of all Choctaw Code Talkers is as follows:

After their initial success, another eleven Choctaw Code talkers were pressed into service. The list of all Choctaw Code Talkers is as follows:

Albert Billy

Ben Carterby

Benjamin Colbert, Jr.

Benjamin Hampton

Calvin Wilson

George Davenport

James Edwards

Jeff Nelson

Joseph Davenport

Joseph Oklahombi

Mitchell Bobb

Noel Johnson

Pete Maytubbe

Robert Taylor

Solomon Lewis

Tobias Frazier

Otis Leader

Victor Brown

Walter Veach

You can read more about their service here. Look for an article next week on Tombstone Tuesday (also Veterans Day) honoring Joseph Oklahombi.

Cherokees serving in the 36th Infantry Division were also pressed into telephone service, tasked with the same mission – confound the enemy. One Cherokee soldier in particular, George Adair, was intensely patriotic and proud to serve.

George could trace his roots back to a Scottish ancestor by the name of James Adair. According to History of the Cherokee Indians and Their Legends and Folk Lore, he counted “this service among the proudest days of his life, for was he not fighting shoulder to shoulder with his kilted kinsmen of Scotland.”

In 1924 Congress granted United States citizenship to all Native Americans. For years, identities were kept secret, but in 2002 long overdue honors and recognition were accorded to all Native American code talkers of both World War I and II. Although many had passed away by that time, we still honor their service to our country. God Bless them all and God Bless America!

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Surname Saturday: Danforth

Danforth

The Danforth surname is a locational or habitational name, possibly meaning “ford in the valley” or someone dwelling in a hidden ford or settlement. It may refer to locations in England such as: Darnford in Suffolk, Great Durnford in Wiltshire or Derford Farm in Cambridgeshire (House of Names).

The name Derneford first appeared in the Domesday Book of 1086 without a surname and may have been a form of the Old English word “Dierneford”. In 1200 the name Darneford (no surname) was recorded in Surrey. There are several spelling variations: Danforth, Danford, Danforde, Danforthe, Damforth and more.

Four early immigrants of the Danforth clan came to New England in 1634: Nicholas Danforth, father and sons Thomas, Samuel and Jonathan Danforth.

Nicholas Danforth

Nicholas Danforth, a minister, was born in 1589 in Suffolk. He married Elizabeth Symmes, but she died in 1629 before the family emigrated in 1634. Nicholas brought his children Thomas, Samuel, Jonathan and daughters Anna, Elizabeth and Lydia. The Danforths were conservative Puritans who fled England to escape religious persecution.

After arriving in the Massachusetts Bay Colony, Nicholas immersed himself in civic affairs as a member of the general court, and became one of Cambridge’s leading citizens. When he died in 1638 he left his land to Thomas, as well as the care of his younger children.

Thomas Danforth

Thomas Danforth was born in 1623, so at the time of his father’s death he was but fifteen years old. By 1643 he had been admitted as a freeman to the colony, granting him the right to vote and to participate in civic affairs. He married Mary Withington in 1644, and like his father, was a conservative Puritan.

At that time, most Puritans would have been especially critical of the Quakers – in 1659 three Quakers were executed by public hanging in Boston. King Charles II was not pleased about the mistreatment of Quakers and demanded they be allowed to express their religious beliefs freely. Thomas helped draft a response to the King, declaring that colonists believed their government ultimately triumphed except in specific cases where there was conflict with English law.

At that time, most Puritans would have been especially critical of the Quakers – in 1659 three Quakers were executed by public hanging in Boston. King Charles II was not pleased about the mistreatment of Quakers and demanded they be allowed to express their religious beliefs freely. Thomas helped draft a response to the King, declaring that colonists believed their government ultimately triumphed except in specific cases where there was conflict with English law.

Thomas participated in the founding of Harvard College, serving as its treasurer from 1650 to 1669. By the 1670’s King Charles was placing more demands on colonists regarding trade and freedom to express one’s religious beliefs. Thomas staunchly opposed those demands and even ran for governor in 1684 – narrowly losing. The loss, however, did grant him some power with the post of deputy governor.

For a brief time in 1692, Thomas Danforth, as acting governor, played a small part in the initial Salem witch trial proceedings. Thomas served as one of the presiding judges of the Superior Court beginning in April.

Having inherited his father’s lands, Thomas started out well and continued to amass wealth and property. He lived near Harvard and also owned a large tract of land (ten thousand acres) in Framingham, once called “Danforth’s Farms.” Thomas and Mary had several children: Sarah, Mary, Samuel, Thomas, Jonathan (two named Jonathan), Joseph, Benjamin, Elizabeth and Bertha. Mary died in 1697, followed by Thomas’ death in 1699.

Samuel Danforth

Samuel Danforth, born in 1626, came to New England with Nicholas in 1634. Following Nicholas’ death, Samuel went to live with Thomas Shepard, pastor of a Cambridge church. By 1643, he had graduated from Harvard, remaining there until 1650 as a tutor. According to Danforth Genealogy, “he was destined for the ministry in accordance with the expressed desire of his mother, who died when he was but three years old.”

Samuel studied astronomy at Harvard and later published three almanacs containing his own original poetry, as well as calendars, tide and astronomical dates and brief bits of New England history. Samuel kept meticulous church records and a journal which contained details of significant events such as the comet Orion in 1652, eclipses and more.

In 1651 he married Mary Wilson and together they had several children, many who died in infancy (and their names used again): Samuel, Mary, Elizabeth, Sarah, John, Mary, Elizabeth, Samuel, Sarah, Thomas, Elizabeth and Abiel, born after Samuel died. Samuel Danforth, pastor of a church in Roxbury at the time, died at the age of forty-eight years in 1674.

Jonathan Danforth

Jonathan Danforth, youngest son of Nicholas and Elizabeth Danforth, was born in 1628. He married Elizabeth Powter in 1654 and a few years later moved to Billerica, a new town established by residents of Cambridge. Like his father and brothers, he participated in civic affairs as a selectman, town clerk and captain of the local militia.

His skills as a land surveyor were put to use as the town of Billerica was settled. He helped lay out farms, towns and highways in Massachusetts and throughout the region. Records indicate that he surveyed parts of New Hampshire as early as 1659. His last survey was dated March 1702, so Jonathan was active well into old age. His surveys of New England helped further expansion and settlement throughout Massachusetts and beyond.

Jonathan and Elizabeth had eleven children: Mary, Elizabeth, Jonathan, John (twice and both died in infancy), Lydia, Samuel, Anna, Thomas, Nicholas and Sarah. Elizabeth died in 1689 and the next year Jonathan married Esther Champney. Jonathan died in 1712 at the age of eighty-five.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

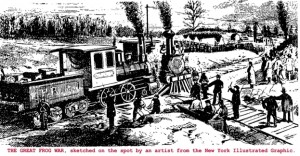

Feudin’ and Fightin’ Friday: The Great Hopewell Frog War

While doing some family research last week, I came across something called a “frog war”. What’s a frog war? I’ve done some “frog” stories, one called “The Battle of the Frogs” and one about an old horned toad named Rip, but this one isn’t about an amphibious creature or a lizard. This one had to do with railroad lines.

While doing some family research last week, I came across something called a “frog war”. What’s a frog war? I’ve done some “frog” stories, one called “The Battle of the Frogs” and one about an old horned toad named Rip, but this one isn’t about an amphibious creature or a lizard. This one had to do with railroad lines.

Hopewell Frog War

In the late eighteenth and into the early nineteenth century, the fledgling new American government began building a series of turnpikes, toll roads and canals to facilitate transportation of goods, as well as westward expansion. A Revolutionary War veteran, lawyer and politician by the name of John Stevens III experimented with steam in the early 1800’s and was the first to construct a steam-powered locomotive in the United States, testing it on a track which ran around his Hoboken, New Jersey estate.

The railroad boom between 1830 and 1860 saw numerous long-distance and regional rail lines established, accompanied by fierce competition for business and less dependence on waterways for transporting goods. New Jersey, on the eastern seaboard, was an important launch point to transport goods westward.

The railroad boom between 1830 and 1860 saw numerous long-distance and regional rail lines established, accompanied by fierce competition for business and less dependence on waterways for transporting goods. New Jersey, on the eastern seaboard, was an important launch point to transport goods westward.

In April of 1846 the Pennsylvania Railroad, or “Pennsy” as it was sometimes called, received its charter to begin the process of surveying and laying track. Its main objective was to provide a link between Philadelphia and the West, as well as compete with the likes of the Baltimore and Ohio (B&O). By 1852, the Pennsy was on-line and doing well – revenues greatly exceeded expectations.

In 1850 the Pennsy had also become the first railroad to operate its own coal mining operations in northeastern Pennsylvania. Steadily the Pennsy would grow to be one of the largest railroads in the country, with an operating budget exceeding that of the United States government, according to Pennsylvania Railroad History. With control of ten thousand miles of track and affiliations with hundreds of other rail lines, the Pennsy was one mighty railroad – considered by some to hold a monopoly.

The Delaware and Bound Brook Railroad (DBB) was established in 1874, a year after New Jersey had passed a law allowing smaller lines to challenge the likes of the Pennsy and compete for routes taking passengers from Philadelphia to New York. The Delaware and Bound Brook would connect Jenkintown in Pennsylvania to Bound Brook, New Jersey and then connect with the New Jersey Central line to Jersey City and beyond.

The Pennsy had a branch in the Hopewell, New Jersey area called the Mercer & Somerset Railway, lying directly in the path of the right-of-way for the Delaware and Bound Brook. To accommodate the “conflict”, the DBB would need to construct a “frog”. In simple terms, a frog refers to the common point where two rails cross, or as the Scotch Plains Times described it in a 1963 article: “an intersection whereby trains on one line cross the tracks of another.”

That shouldn’t have been a big deal, as the newspaper continued, “normally frogs could be laid with no more noise than the sound of sledges striking spikes.” This frog was different because it audaciously challenged the Pennsy monopoly in western New Jersey. On the morning of January 5, 1876 the DBB would lay down the gauntlet, so to speak – but not without a show of Pennsy might.

The Pennsy had little regard for the law passed in 1873 and sent a train to sit idling at the exact spot where the frog was to be installed. When the 7:15 a.m. southbound Mercer & Somerset was approaching (an affiliate of the Pennsy), the Pennsy train was backed onto a siding. However, DBB workers had been watching from surrounding bushes and suddenly ran out toward the sidelined train.

DBB workers placed steel rails and wooden ties in front of the Pennsy train, chained it to the tracks, and erected a barrier to prevent other trains from coming through until they were able to lay down the frog. Pennsy headquarters got wind of what was happening and sent their own men to board a locomotive at Millstone, proceed to Hopewell and ram through the barricade.

DBB workers placed steel rails and wooden ties in front of the Pennsy train, chained it to the tracks, and erected a barrier to prevent other trains from coming through until they were able to lay down the frog. Pennsy headquarters got wind of what was happening and sent their own men to board a locomotive at Millstone, proceed to Hopewell and ram through the barricade.

The train from Millstone headed west to Trenton and then turned northward toward Hopewell at an incredible speed for that day – thirty-one miles in thirty minutes! A DBB locomotive had been pulled up to protect the area where the frog was to be installed, but the Millstone train, seeing no impediments at all, rammed through the barricade and into the DBB train. As you might imagine, this little “frog war” caused quite a stir in the surrounding area.

Both railroads sent reinforcements, the Pennsy sending a train which could feed up to six hundred men if necessary. Seeing hundreds of railroad workers facing off, with hundreds of spectators and the press watching, the Mercer County sheriff called on New Jersey governor Joseph Bedle to send the militia.

The militia arrived around midnight and you’d think things would calm down and no further challenges from either side would be made. However, the next morning it became apparent that the locals were standing with DBB when they helped ripped up Pennsy track, forcing the Pennsy engineer to head out over a trackless area – the crowd cheered at the departure.

The courts, enforcing the law on the books, quickly ruled that the Pennsylvania Railroad had no right to interfere with the frog-laying by the Delaware and Bound Brook. The Pennsy agreed to abide by the law, and the militia made a regal affair out of their “victory” by dressing up in full uniform and reading the court order at a ceremony.

he Pennsy wrecks were hauled away, and as the crowd watched, the frog was put in place at 2:00 p.m. on January 8. DBB Locomotive No. 37 was the first train to cross the frog. The “Great Hopewell Frog War” was thus concluded and had brought an end to railroad monopolies in New Jersey. Perhaps the Reading Railroad liked the DBB’s “moxie” – in 1879 they leased the Delaware and Bound Brook for 999 years, essentially merging the two lines.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

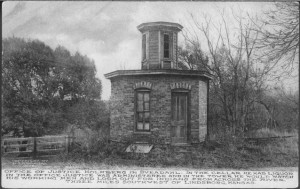

Ghost Town Wednesday: Sveadal (McPherson County, Kansas)

I’ve been reading a series of books about Swedish immigrants who came to America and settled in central Kansas beginning in the late-1860’s. According to the Kansas Historical Society, eastern immigration companies sent agents to Europe to encourage settlement in the western part of America. For many Europeans it was seen as an opportunity to have access to good farm land and a chance to make a better life for their families. Many of those Swedish communities that sprung up in central Kansas are still around today and thrive. Today’s ghost town, obviously, was one that didn’t make much of itself.

I’ve been reading a series of books about Swedish immigrants who came to America and settled in central Kansas beginning in the late-1860’s. According to the Kansas Historical Society, eastern immigration companies sent agents to Europe to encourage settlement in the western part of America. For many Europeans it was seen as an opportunity to have access to good farm land and a chance to make a better life for their families. Many of those Swedish communities that sprung up in central Kansas are still around today and thrive. Today’s ghost town, obviously, was one that didn’t make much of itself.

In 1868 Major Leonard N. Holmberg, a man claiming to have royal Swedish blood coursing through his veins, came to the area in Kansas which would later become McPherson County. The story goes that he had been a lieutenant in the Swedish army and had been given the position of Major in the Union Army during the Civil War. Thereafter, he preferred to be referred to as “Major”.

In 1868 Major Leonard N. Holmberg, a man claiming to have royal Swedish blood coursing through his veins, came to the area in Kansas which would later become McPherson County. The story goes that he had been a lieutenant in the Swedish army and had been given the position of Major in the Union Army during the Civil War. Thereafter, he preferred to be referred to as “Major”.

Holmberg named the town he proposed to build on his property “Sveadal”, a derivative spelling of his homeland Sweden, and built a general store. In 1869 he was appointed as both the postmaster and justice of the peace, but according to Ghost Towns of Kansas, “the latter was a dubious title since he always carried a gun and often used it to scare his farm laborers, just to ‘get ‘em going.’”

His neighbors on the other side of Smoky Hill River weren’t too happy about how he treated his fellow man – some claimed he was “possessed of the devil.” His reputation didn’t earn him any high marks and he eventually lost his government positions. In addition to the general store, Holmberg had built an odd-looking eight-sided house with a wooden tower which he used to watch his farm laborers and keep an eye out for Indians.

The general store would also become the first court house and on March 6, 1870 a meeting was held there to organize McPherson County. Even though there wasn’t much to Sveadal at that time, it was named temporary county seat after an election held on May 2. That summer a military company was organized and Major Holmberg took command of the unit.

Settlers were still streaming to the area, but by 1871 Sveadal showed little sign of growth or the promise of future growth. Whether that was due to the behavior and reputation of its “leading citizen” is not clear. Nevertheless, the post office was closed that year and the county seat was moved to nearby Lindsborg. Lindsborg, another Swedish settlement, and perhaps built on more solid values and reputation, would thrive and Sveadal would fade away.

Settlers were still streaming to the area, but by 1871 Sveadal showed little sign of growth or the promise of future growth. Whether that was due to the behavior and reputation of its “leading citizen” is not clear. Nevertheless, the post office was closed that year and the county seat was moved to nearby Lindsborg. Lindsborg, another Swedish settlement, and perhaps built on more solid values and reputation, would thrive and Sveadal would fade away.

For the 1875 Kansas census and the 1880 United States census, Leonard Holmberg was enumerated as a farmer and resident of the Smoky Hill township. In the late 1980’s when Ghost Towns of Kansaswas published, the courthouse/general store was still standing and being used for a tool shed, situated on the outskirts of Lindsborg.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

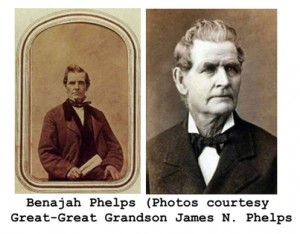

Tombstone Tuesday: Benajah Spelman Phelps (1800-1903)

I was trolling through Vermont cemeteries looking for a subject for today’s article when I came across four graves in the Alburgh Tongue Cemetery in Grand Isle County, all children of “B.S. (or Benajah S.) and Asenath Phelps” … hmm. The children were: Belinda, Cynthia, Horace and Ruth. The grave stone pictures are hard to distinguish as far as dates but it appears that at least three of their children were very young when they died. Their parents Benajah Spelman and Asenath (Fletcher) Phelps are buried, however, in Fond du Lac, Wisconsin… double-hmm.

I was trolling through Vermont cemeteries looking for a subject for today’s article when I came across four graves in the Alburgh Tongue Cemetery in Grand Isle County, all children of “B.S. (or Benajah S.) and Asenath Phelps” … hmm. The children were: Belinda, Cynthia, Horace and Ruth. The grave stone pictures are hard to distinguish as far as dates but it appears that at least three of their children were very young when they died. Their parents Benajah Spelman and Asenath (Fletcher) Phelps are buried, however, in Fond du Lac, Wisconsin… double-hmm.

I found that Benajah lived a very long life, dying at age one hundred and three in Colorado Springs, Colorado – again with the “hmm”. Talk about an intriguing history to investigate — so off I went on the search for more about Benajah.

Benajah Spelman Phelps was born on March 24, 1800 on South Island, Grand Isle County, Vermont to parents Abel and Mary (Pelton) Phelps, their second son. His fourth great-grandfather, William the immigrant, was born in 1599 and Benajah’s great-grandfather Captain Abel Phelps was a Revolutionary War veteran. Benajah’s father was a veteran of the War of 1812. In fact, the island where the family lived was in the middle of Lake Champlain, scene of significant battles which occurred in both the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812.

Benajah Spelman Phelps was born on March 24, 1800 on South Island, Grand Isle County, Vermont to parents Abel and Mary (Pelton) Phelps, their second son. His fourth great-grandfather, William the immigrant, was born in 1599 and Benajah’s great-grandfather Captain Abel Phelps was a Revolutionary War veteran. Benajah’s father was a veteran of the War of 1812. In fact, the island where the family lived was in the middle of Lake Champlain, scene of significant battles which occurred in both the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812.

In 1901 a New York magazine called The Outlook provided the details of the September 11, 1814 battle through the eyes of Benajah, just fourteen years old on that day. Eighty-seven years later Benajah well-remembered the day, “just the same as if it was yesterday.” His father, a farmer was an “orderly sergeant in the milishy”. Abel knew the British had intentions to attack Plattsburgh, New York just across the bay, so knowing he must go and serve with his company he left Benajah in charge of the farm.

On the morning of the September 11, the family arose early, and seeing the British ships in the distance, hastened to leave their home and proceed to a hill about two miles away where they could have a better view of the action. Benajah gave a colorful account in his interview for The Outlook – you can read it here.

One of the things he remembered most was the blood – blood everywhere. After the fighting had ended, he took his family home so he could perform his evening chores. The family was, of course, concerned about Abel and his safety, but he eventually returned to his family and the British had retreated something during the night following the battle. In 1901, Benajah surmised that the British had intended to take Plattsburgh and keep on marching all the way to Washington. Eighty-seven years later he was still elated with the American defeat of the British:

You know General Prevost started from Montreal with thirty thousand soldiers. He calc’lated to go straight to Washington and burn every town and city he came to. That’s what he was calc’latin’; but – here Mr. Phelps indulged in a chuckle of intense satisfaction – he didn’t even git through the first county! No sir! He didn’t. Lost five hundred men, too, and all his shippin’. The British wanted the lake the worst kind. If they could git control of it, it would be very handy for transportin’ men and supplies. But they didn’t git it.

On November 7, 1824, Benajah married Asenath Fletcher, daughter of Calvin and Lydia (Dixon) Fletcher in South Hero, Grand Isle County. The first census record (1850) listing all family members enumerated their children as: Abel (21); Sarah (16); Frederick (14); Charles (12); George (10); Marietta (7) and Lydia (5). Their oldest child, Calvin, was married in 1850 and living in Clinton County, New York (same county as Benajah) with his wife and young family.

On November 7, 1824, Benajah married Asenath Fletcher, daughter of Calvin and Lydia (Dixon) Fletcher in South Hero, Grand Isle County. The first census record (1850) listing all family members enumerated their children as: Abel (21); Sarah (16); Frederick (14); Charles (12); George (10); Marietta (7) and Lydia (5). Their oldest child, Calvin, was married in 1850 and living in Clinton County, New York (same county as Benajah) with his wife and young family.

I’m guessing that there were two or three children born between Calvin and Abel, and those may have been some of those listed at Find-A-Grave as the infant children of Benajah and Asenath. Benajah was likely a farmer, among other things. A Vermont geology report indicates that in 1834 Benajah and a business associate named Horace Wadsworth built a hotel called the “Mansion House” in Alburgh. The reason the hotel would be mentioned in a geology report, I presume, is because Alburgh was known for its “medicinal waters”.

In 1836, records of the Vermont legislature indicate that Benajah was “inspector of hops” for Grand Isle County. I presume that had something to do with the business of brewing spirits. According to early New England history, hops was an important crop during colonial days and became more commercially important in the late eighteenth century. This may have been a trade or skill passed down in Benajah’s family because hops had been a major crop in the Tewksbury area of England where his ancestors lived.

The next public record I found for Benajah was a notice in the Burlington Weekly Free Press on December 2, 1842 – apparently Benajah had declared bankruptcy, so perhaps he had over-extended himself with the hotel. By 1850, he had moved his family across the bay and into New York’s Clinton County where oldest son Calvin also resided.

In son George’s obituary years later it was noted that George and his family moved to Fond du Lac, Wisconsin when he was a young boy, so perhaps Benajah moved his family west not long after the 1850 census. In 1860 he was a farmer in Fond du Lac and five of his children were still residing at home: Frederick, Charles, George, Mariette and Lydia.

On June 1, 1865, Asenath died at the age of sixty-two and was buried in Fond du Lac’s Empire Cemetery. After her death, it appears that Benajah lived with his children at various times until his death. No record could be found of him in 1870, but it’s likely he was still in Fond du Lac because his children and their families were enumerated there (his name was often misspelled on census records).

In 1880, Benajah was living with George and his family in Taylor County, Wisconsin, eighty years old and a gardener. Sometime between 1880 and 1900, George moved west to Colorado Springs, Colorado and was the proprietor of Phelps Hotel in 1900. His one hundred year-old father Benajah was living with him and his family. The following year, Benajah would become somewhat of a celebrity as articles began to be published about his amazing longevity.

The Outlook article published in 1901 began by introducing Benajah to its readers:

On a typical New England March day, seven months more than one hundred and one years ago, in an island on Lake Champlain, Benajah Phelps first opened his eyes on scenes of earth. It seems as if there entered his physical constitution that day something of the ruggedness of the New England winter and of the strength of his native hills, for still he abides among us. Perhaps when in accord with the pious custom of New England, he was named Benajah, after him of Kabzeel, the captain of David’s guard, there came upon him something of the superb physical endowment of this son of Jehoiada, who slew a lion in the pit in time of snow and laid low “an Egyptian, a man of great stature, five cubits high; and in the Egyptian’s hand was a spear like a weaver’s beam; and he went down to him with a staff, and plucked the spare of the Egyptian’s hand, and slew him with his own spear.” However this may be, Mr. Phelps is not only living but very much alive.

He was interviewed on his one hundred and first birthday, and when asked about his health, declared that it was “toler’ble, toler’ble. I don’t eat much meat. I’m gettin’ old. My teeth ain’t as good as they was.” He was described as an observant and intelligent man and was proud to have voted in the last presidential election in the “woman-suffrage State of Colorado”.

He was interviewed on his one hundred and first birthday, and when asked about his health, declared that it was “toler’ble, toler’ble. I don’t eat much meat. I’m gettin’ old. My teeth ain’t as good as they was.” He was described as an observant and intelligent man and was proud to have voted in the last presidential election in the “woman-suffrage State of Colorado”.

On November 21, 1903, Benajah Phelps “passed away very quietly, the lamp of his life merely flickered out”, according to his obituary in the Colorado Springs Weekly Gazette. By that point in his life, he had “no property to dispose of, but in his dreams and fancies he often imagined that he was on the farm and that he must sell portions of it for one purpose or another.” He was taken back to Fond du Lac and buried next to Asenath.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Military History Monday: The Battle of Middle Creek

I’ve been reading an excellent book about James Abram Garfield, the twentieth President of the United States (look for a book review soon). I didn’t really know that much about him, except that he was assassinated not long after he was inaugurated in 1881. Not a lot of books have been written about him, but he lived an amazing life, rising from poverty to the presidency.

I’ve been reading an excellent book about James Abram Garfield, the twentieth President of the United States (look for a book review soon). I didn’t really know that much about him, except that he was assassinated not long after he was inaugurated in 1881. Not a lot of books have been written about him, but he lived an amazing life, rising from poverty to the presidency.

One event that caught my attention, and made him famous, was the Civil War Battle of Middle Creek in eastern Kentucky. The description provided by author Candice Mallard reminded me of the Bible story of Gideon and his rout of the Midianites.

James Garfield had been pursuing an academic career as a professor, and later president of the Eclectic Institute, when an Ohio state senator died unexpectedly. Garfield was asked to take his seat and later won it outright. When the Civil War began, he was eager to enlist, although Ohio Governor William Dennison, Jr. convinced him his service in the legislature was needed more urgently at the time.

James Garfield had been pursuing an academic career as a professor, and later president of the Eclectic Institute, when an Ohio state senator died unexpectedly. Garfield was asked to take his seat and later won it outright. When the Civil War began, he was eager to enlist, although Ohio Governor William Dennison, Jr. convinced him his service in the legislature was needed more urgently at the time.

In the summer of 1861 Garfield entered the Union Army as a lieutenant colonel, and after reaching the age of thirty in November, was promoted to full colonel. His first task was to assemble the 42nd Ohio Regiment which he would command. Defending Kentucky, a strategic border state, from Rebel advances, was his first assignment. Kentucky was also the birth home of President Abraham Lincoln, who emphasized, “I hope to have God on my side, but I must have Kentucky.”

As it turned out, however, Garfield and his regiment were outnumbered (not to mention inexperienced) and faced an Confederate general, Humphrey Marshall, who had graduated from West Point in 1832, one year following Garfield’s birth. Garfield, an academic, was up against Marshall, a seasoned military tactician.

Still, Garfield didn’t hesitate to take on the challenge – his first step was to pour over maps of eastern Kentucky so he could familiarize himself with the area his troops had been tasked to defend. The battle for eastern Kentucky, however, would come down to one decisive campaign in early 1862.

Garfield and his troops (which included not only the 42nd Ohio Infantry but the 14th and 22nd Kentucky Infantries) departed on their mission in November of 1861. In the early days of January 1862 they were approaching Paintsville, Kentucky where Marshall’s troops were encamped. The Rebels, although outnumbering Garfield’s troops, were low on both supplies and morale. At that time Garfield was about eighteen miles away, so instead of advancing on the enemy, Marshall decided to stay put, hold Paintsville and see what transpired.

Marshall must have realized that it would have done him little good to attempt a direct attack because of the lack of supplies. Garfield also knew that he, with mostly “green” recruits, was not only outnumbered but “out-experienced” – plus the fact that the Kentuckians weren’t all that well-armed or likely predisposed to be fighting their fellow Kentuckians in the first place. Like Marshall, Garfield could have decided to just sit and wait.

Instead, Garfield, according to Garfield: A Biography by Allan Peskin, “a strong believer in ‘vigorous and well directed audacity,’ was eager for action.” His staff was far more cautious and advised he wait, but instead Garfield was determined to advance. At the time, the 40th Ohio had not yet caught up to the 42nd and the Kentuckians under Garfield’s command. Considering that, his plan going forward was indeed audacious – Garfield chose to divide the small force into three detachments and try to deceive the Rebels into believing they were facing a much larger force.

There were three roads leading into Paintsville and Garfield began by sending the first detachment down the river road. Marshall had already stationed Confederate pickets along each road leading to the town, so it wasn’t surprising when the two sides met. Garfield’s troops made a lot of noise, which after the Confederates reported back to Marshall, brought more Rebels to defend the river road.

About an hour later Garfield sent the second detachment up the second road, also making lots of noise. Marshall sent reserves not already fighting the first Union detachment down that road. Garfield’s last detachment was sent down the third road, and in the ensuing skirmishes, Marshall’s forces became convinced (wrongly, of course) that they were facing an overwhelming force. Already low on morale and scurrying about to respond to Garfield’s “advances”, the Rebels instead decided to flee from the area, leaving Paintsville deserted.

From this point on, the Rebels were forced to continue retreating toward Prestonsburg and the Middle Creek area. In the meantime the 40th Ohio arrived under the command of Colonel Cranor. Cranor wanted his men to rest before continuing on, but Garfield wanted to seize the opportunity to pursue Marshall.

Around noon on January 9, about eleven hundred men with three days of rations, started in the direction of the fleeing Rebels. As they drew closer to Marshall’s position it became apparent they were about to encounter the enemy, so Garfield sent word back to Paintsville to send reinforcements. That night his troops spent the night shivering in an icy cold rain, too near enemy lines to risk camp fires.

As it turned out, Marshall’s troops on the very same night had become dispirited enough to demand retreat from Kentucky. At three o’clock on the morning of January 10, Garfield rallied his troops and an hour later were again advancing toward their target. Garfield thought Middle Creek would be a good place for his troops to entrench themselves, thinking that Marshall was a few miles upstream at Abbot’s Creek.

Instead, as they approached Middle Creek, shots were exchanged with the Rebels. By midday they had seized one prisoner. Garfield paused at one spot and could see enemy positions in the distance. His plan had been to cut off Marshall’s retreat, but instead realized he was now facing most of Marshall’s troops.

Again, however, Garfield chose audacity. He sent two companies to clear one side of the valley of Rebels, and then instead of waiting to see the results, he ordered the rest of his troops into a battalion drill, marching as if they were on parade – “for the sake of bravado and audacity”.

Very recent history would be repeating itself, because his intention again was to make the Rebels think they were facing a more overwhelming force. It worked because Marshall later related that he was convinced that Garfield had at least five thousand men. Even with the deception and ensuing confusion, it wasn’t an easy victory, with each side advancing and falling back throughout the day. As Peskin wrote:

This was the pattern of the day’s fighting: a succession of uncoordinated charges and withdrawals, with a great deal of shooting and very little bloodshed – a “regular ‘bushwacking’ battle.” Garfield handled his troops with little imagination or enterprise, flinging them against the rebel line in driblets, never committing more than two or three hundred at any one time. . . Marshall, for his part, fought a completely passive battle, content, by and large, merely to maintain his original position. At various times during the afternoon a well-directed charge could have sent Garfield’s disorganized men reeling down the valley, but Marshall did not really want a victory. He was satisfied to continue his retreat in peace.

As Civil War battles went, this one wasn’t particularly bloody, although there were casualties – and more on the Confederate side. After the battle ended, however, both sides greatly exaggerated the others one’s casualties – Garfield was sure at last 125 Confederates had been killed and Marshall thought his troops had killed 250 and wounded another 300. Who knows what would have happened, for either side, had Marshall and his troops not been confused and dispirited by Garfield’s deceptive tactics in the first place at Paintsville.

For James Garfield, it earned him a reputation for “bravado and audacity” and a promotion to brigadier general. That’s not to say his triumph didn’t give him pause. As author Candice Mallard related in her book, Destiny of the Republic, Garfield, upon seeing the enemy mortally wounded and strewn about, realized he was responsible for the carnage. She continued: “It was in that moment, Garfield would later tell a friend, that ‘something went out of him . . . that never came back; the sense of the sacredness of life and the impossibility of destroying it.’”

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Surname Saturday: Brinson

Brinson

I don’t usually write about surnames from my own family tree, but I’ve been researching this line a bit and there are some pretty interesting characters – so why not? One of my ancestors appears to be perhaps the first Brinson to immigrate to America in 1677. But, first a bit about the origins of the surname. This one has several theories and they are as follows:

House of Names – The Brinsons lived in the village of Brinton in County Norfolk. The name was first found in Herefordshire where a family seat had been held from ancient times, and well before the Norman Conquest. Interesting, because another source believes the name actually had French (Normandy) origins and came to England as a result of the Norman Conquest.

Internet Surname Database – Brinson is of Old French origin, originally a locational name from “Briencun” in Normandy. Presumably following the Norman Conquest, a family assigned a place name as “Brimstone Hill” in County Essex. This source also adds that the name may derive from a form of the Middle English word “brem(e)” or “brim(me)” (vigorous or fierce), which was originally derived from an Olde English word “breme” – add “-son” to it and you get “Brimson” (close). For more information click the link above.

4Crests – This was a locational name ‘of Branston’, a parish in a Lincoln diocese. If so, the name might have originally derived from an Old English word “Branstun” which mean someone who lived where broom grew.

Like the Internet Surname Database, both Ancestry.com and New Dictionary of American Family Names believe the surname origin is French, which of course, was likely introduced in England following the Norman Conquest. Interestingly, none of these sources mentions County Devon in England, which is where my ancestors hailed from.

Daniel Brinson (1653-1696)

Daniel Brinson was born on September 8, 1653 in County Devon, England to William and Margaret Brinson. Records show that Daniel arrived on these shores in 1677, according to The Philadelphia and Bucks County Register of Arrivals:

Daniel Brinson of membury parish in ye County of Devon – arived in this River the 28 day of the 7th month 1677 in the Willing mind of London of m[ast]er Lucome. maryed to ffrances green land of East Jersey the 8th day of the 8th month 1681.

In early records, the family name was sometimes referred to as “Brunson”, “Brynson”, “Brymson” or “Brimson”. One reference, the Somerset County Historical Quarterly (Volume III, 1914), has quite a bit of information on the Brinson and Greenland families, although I believe some of it to be incorrect based on more recently located historical records (more on that below).

In early records, the family name was sometimes referred to as “Brunson”, “Brynson”, “Brymson” or “Brimson”. One reference, the Somerset County Historical Quarterly (Volume III, 1914), has quite a bit of information on the Brinson and Greenland families, although I believe some of it to be incorrect based on more recently located historical records (more on that below).

As mentioned in the register of arrivals record above, Daniel married Frances Greenland on October 8, 1681. Frances’ father Dr. Henry Greenland was a prominent citizen, said to have been the first to settle in Princeton, New Jersey. According to Princeton history, Dr. Greenland built a “house of accommodation” (tavern) there in 1683 and part of it still survives as part of the Gulick House, an historic landmark.

Daniel settled along the same highway around 1685 on land that is the site of another historical site known as “the Barracks”. That house was built by Richard Stockton, one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence, and may have been used during the French and Indian War to house soldiers.

Daniel settled along the same highway around 1685 on land that is the site of another historical site known as “the Barracks”. That house was built by Richard Stockton, one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence, and may have been used during the French and Indian War to house soldiers.

Daniel may have had a violent temper and abused Frances, according to Riots and Revelry in Early America:

While court records for seventeenth-century New Jersey are relatively sparse, we do know, for example, that in 1694 Doctor Henry Greenland appeared in the Middlesex Court of quarter sessions on behalf of his daughter Frances to complain that she had been abused by her husband, Daniel Brynson.

In 1693, Dr. Greenland patented four hundred acres of land about a mile from what is today Princeton University, on the Millstone River, and on this plantation Daniel Brinson lived until his death in 1696. The children that Daniel and Frances had were: Barefoot, Margaret, Mary and Anne. According to Patents & Deeds & Other Early Records of New Jersey 1664-1703, an nuncupative (oral) will was recorded on June 9, 1696:

Nuncupative Will of Daniel Brymson of Milston R. declarede before Mary Davis, Sarah Gannett, Jonathan Davis and Samuel Davis. Wife Francis dau. of Dr. Greenland, son Barefoot, eldest daughter Ruth and apparently other children, Real and personal property. Proved Sept. 15, 1696.

After Daniel died, Frances married a Quaker, John Horner.

Barefoot Brinson

Barefoot Brinson was born in 1686 and said to have been named after his grandfather Henry Greenland’s friend, Dr. Walter Barefoote (who is also mentioned in Henry’s will). The Somerset County Historical Quarterly described Dr. Barefoote in this manner:

. . . Dr. Walter Barefoot (or Barford, as the name is given in England) who came to Kittery, Maine, in 1656 or 1657, and for thirty years till his death, 1688, was said to be the most litigating and scandal-raising personage connected with the Piscataqua region, whether as doctor, captain, prisoner, prison-keeper, Deputy Governor, land speculator or Chief Justice. He was well-educated and wrote a good hand. He was a churchman, but a sturdy and quarrelsome supporter of the Stuart policy, while most of his neighbors were Puritans. . .

I couldn’t locate an exact marriage record, but most family researchers believe Barefoot married Mary Lawrence (or Marritje Laurence Popinga) around 1721. At least two children, John and Ruth, were mentioned in his will. I believe, however that the Somerset County Historical Quarterly record was incorrect in saying that John married a woman by the surname of Arrowsmith, although I suppose she could have been a first wife.

Our research indicate that Barefoot’s son John married Hannah Anne Stout. Barefoot’s will was written in 1742 or 1743 and one of the witnesses was Joseph Stout, probably Hannah’s uncle, so John marrying into the Stout family seems more likely. It is presumed that Barefoot died sometime in 1748 because his will was proved on May 13 of that year.

On November 21, 1748 Mary Brunson (an alternate spelling) advertised about three hundred acres of land for sale in the New York Gazette. Executors for Barefoot’s will were Mary Brunson and Thomas Lawrence (her brother I presume).

Barefoot was also sheriff of Somerset County, New Jersey and according to History of Princeton and Its Institutions, Volume 1, serving until his death in 1748.

The Brinson family eventually made their way to Pulaski County, Kentucky and intermarried with the Earps, the family of my grandmother Okle Emma Erp (family changed spelling of name, as the legend goes, to distance themselves from their infamous relative Wyatt Earp). Just as I was concluding research for this article, I found a record that indicates that Daniel Brinson bought land from Thomas Budd on February 10, 1685, who it looks like may have been the grandfather of Mary Budd. Mary Budd married Joshua Earp, who is the common ancestor I share with Wyatt Earp, my third cousin three times removed.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!