Digging History Magazine – North and South: Profiles in Courage

When I decided to feature a Civil War theme for the April issue of Digging History Magazine, I knew I needed to find two compelling stories of men who fought on opposite sides. While researching stories for the March issue related to the Zimpelman family (“Who Were You Roy Simpleman?” and “Feuding and Fighting: The El Paso Salt War”), I decided the character I would feature to represent the Confederacy was George Bernhard Zimpelman, a German-born Texan. What I didn’t fully realize was just how valiantly he served.

When I decided to feature a Civil War theme for the April issue of Digging History Magazine, I knew I needed to find two compelling stories of men who fought on opposite sides. While researching stories for the March issue related to the Zimpelman family (“Who Were You Roy Simpleman?” and “Feuding and Fighting: The El Paso Salt War”), I decided the character I would feature to represent the Confederacy was George Bernhard Zimpelman, a German-born Texan. What I didn’t fully realize was just how valiantly he served.

I also looked for a Union soldier to feature and found the riveting story of Francis Jefferson Coates. He grew up as a Wisconsin farm boy and joined the much-heralded “Iron Brigade”, an amalgamation of hard-scrabble farmers and lumberman of Wisconsin. After being wounded at South Mountain he was promoted to corporal and later sergeant, about four months before Gettysburg. Gettysburg would be his last military battle, but not his final life challenge.

Two different backgrounds, two brave soldiers, two powerful stories. The April issue is available on sale as a single issue, or start a subscription of any length (3-month, 6-month or one year) and receive it as your first issue.

Sharon Hall, Publisher and Editor, Digging History Magazine

Adventures in Research: Solving Family History Mysteries (Digging and DNA)

I love what I do — helping clients discover who they are, where they came from, did their ancestors make history (good or bad) and more. I take a slightly different approach perhaps than many genealogists who are looking for land and census records and clipping obituaries. I look for those too, but what I really enjoy finding are the stories. I never know what I’ll uncover. When I come across something that is either challenging or unexpected (a real “family history mystery”) you can expect to see it written about in Digging History Magazine. I want to share what I’ve learned in hopes of helping other researchers who are challenged by their own “family history mysteries”.

I love what I do — helping clients discover who they are, where they came from, did their ancestors make history (good or bad) and more. I take a slightly different approach perhaps than many genealogists who are looking for land and census records and clipping obituaries. I look for those too, but what I really enjoy finding are the stories. I never know what I’ll uncover. When I come across something that is either challenging or unexpected (a real “family history mystery”) you can expect to see it written about in Digging History Magazine. I want to share what I’ve learned in hopes of helping other researchers who are challenged by their own “family history mysteries”.

One such memorable mystery actually began right around the time I began writing articles for the Digging History blog. One of the first articles I wrote was to commemorate the 100th anniversary of a tragic coal mine explosion in Dawson, New Mexico. Approximately one month later I wrote a “Feudin’ and Fightin’ Friday” article about a seemingly obscure Texas feud. Turns out the two articles were amazingly linked, something I wouldn’t discover until contacted by someone in 2015 requesting a change in the Dawson article.

As an editor, the request, ironically, involved a misspelled name. It had been misspelled in the newspaper article used as a source and Doug Simpleman, great grandson of the man with the misspelled name, wanted to set the record straight. In fact Doug had been working for awhile to set the record straight about Roy Simpleman — and to find out who he really was. You see, Roy had been born as Refugio Badial, the illegitimate son of Ramona Badial. How did he become Roy Simpleman?

Doug contacted me in July of 2015 and by September we were reconnecting about the article and Doug’s ongoing research. On September 19 we exchanged a flurry of emails back and forth for about four hours. Then, everything began to fall into place — who Roy really was and that his likely birth father was the son of a German immigrant, George B. Zimpelman. A Y-DNA test would soon prove Doug’s theories. Doug and I reconnected recently when I decided to include the story in the March issue. I’ve since uncovered even more details and was able to significantly enhance the Texas feud story. It wasn’t an insignificant event, but one that had been simmering for years in the post-Reconstruction era.

It was such an interesting research adventure, and despite my part in it being rather minuscule, I had to write about it. As a matter of fact, I’m still writing about it as I’ve uncovered more about the Zimpelman family. Several days ago I contacted other members of the Zimpelman family and now they are becoming aware of this amazing story.

By the way, the Zimpelman saga continues next month as April will feature a focus on stories from the Civil War. This month’s story arc includes not only the “family history mystery” but an updated article on the El Paso Salt War. Additionally, a ghost town story and a repeat of the Dawson mine explosion article are both related to Doug’s family history mystery.

One good story begets another, I say! Read the entire story arc (and more) in the March issue, available on sale here. Or, purchase a subscription here (buy a subscription during March and it will begin with March issue).

Keywords: Family history mystery, Roy Simpleman, George B. Zimpelman, George Walter Kyle Zimpelman, El Paso Salt War, solving genealogy problems with DNA, breaking down brick walls with DNA, Digging History Magazine, Dawson New Mexico 1913 mine explosion, Digging History, mining history, historic mine disasters.

Galveston: Ellis Island of Texas and the Storm That Changed Everything

Here are some excerpts from the March issue of Digging History Magazine. It’s packed with stories, beginning with a series of articles on Galveston, Texas:

Here are some excerpts from the March issue of Digging History Magazine. It’s packed with stories, beginning with a series of articles on Galveston, Texas:

- Galveston: The Ellis Island of Texas

- The Storm That Changed Everything

- Isaac Cline’s Fish Story

So much emphasis has been placed on Ellis Island, and certainly thousands of immigrants passed through there (as well as other ports like Baltimore and Philadelphia). However, many immigrants actually came through Gulf of Mexico ports like New Orleans and Galveston. If immigrants were headed for the American Midwest states and territories of Kansas, Missouri and Nebraska, Galveston landed them hundreds of miles closer to their destination than arriving at an Atlantic port.

The first residents of the island weren’t the most welcoming. One historian called the Karankawas, whose presence on the island dates back to the 1400s, a “remarkably antisocial tribe”. Although thought to have been cannibalistic, evidence seems to indicate that is probably not true.

Between 1817 and 1821 it was home to Jean Lafitte and his band of pirates. Following their departure the Port of Galveston was established as a small trading post in 1825. By 1835 it was the home port of the Texas Navy.

Norwegian and Swedish immigrants began arriving in Texas in the 1830s and 1840s, some over land and some making entry at Galveston. Most notably during this same time period, large groups of German immigrants also arrived in the port.

By the late nineteenth century and early twentieth Galveston had become a cosmopolitan gateway city. What happened to the city in early September 1900 would change everything, however. A storm which had been birthed thousands of miles away along the western coast of Africa was about to impact the Gulf of Mexico, something Isaac Cline, Galveston’s resident meteorologist, had stated nine years earlier could never happen. How wrong he was.

Thousands of tourists were on the beach, restaurants were full and a massive storm was about to wipe out much of the beach city of Galveston.

Even today no one seems sure just how many people died, except to say that it was the most disastrous hurricane in history – estimates range from six to eight thousand fatalities. Cora’s body was later found on September 30 underneath the very wreckage that Isaac, his daughters and Joseph clung to during the height of the storm. Her body was identified by her wedding ring. Among the dead were ten nuns and ninety children of the St. Mary’s Orphans Asylum.

By the following day, headlines across the country began to report the tragedy, albeit having somewhat sketchy details to report since Galveston’s communication lines had been severed in the midst of the storm. Survivors were met with horrible conditions in the aftermath. Corpses of both humans and animals were strewn about everywhere. Early on Monday, September 10, efforts were underway to try and bury the humans. City officials, however, abandoned that plan – there were simply too many bodies. By Monday afternoon they were planning to have a mass burial at sea.

The bodies would have weights attached and transported out into the Gulf on barges. This was a gruesome task, to say the least, and to entice men to carry it out the city offered free whiskey. Enough men signed up, but after becoming exceedingly drunk, were incapable of securing the weights properly, causing hundreds of bodies to wash back up on the beach on Tuesday morning. The only option left was to burn the bodies. The smell of burning flesh and plumes of smoke hung in the air for several weeks.

Isaac Cline’s Fish Story

The Galveston hurricane notwithstanding, Isaac Cline had witnessed some unusual weather events during his career. Probably the most unusual one sounds like a far-fetched tall Texas fish tale — how it happened and why it happened were astonishingly true, however.

Isaac Cline had witnessed some unusual weather events during his lifetime. Following his graduation from medical school in March of 1885 Cline was assigned to the weather station at Fort Concho near San Angelo, Texas. Weather was what he was always interested in apparently, yet he received a medical degree to claim a scientific background. Instead, he surmised he could study weather and its affects on people, thus welding the two disciplines.

Isaac must have thought he’d arrived in hell. The landscape was largely barren and it was hotter than Hades during the summer months. The Concho River was dry during this particular season of the year. Yet, one evening in August as Isaac was strolling along, crossing the bridge over the river, he was startled to hear a distant roar. Was it thunder? No, but it wasn’t long before he saw with his own eyes where it was coming from.

Read the rest of these stories (and more) in the March issue, available on sale here. Or, purchase a subscription here (buy a subscription during March and it will begin with March issue).

Keywords: Cleng Peerson, Ellis Island of Texas, Erik Larson, Fort Concho, Galveston, Hotel Galvez, Isaac Cline, Isaac Cline fish story, Isaac’s Storm, Jean Lafitte, Jewish immigration, Karankawa, New York of the Gulf, Norwegian immigration, San Angelo Texas, St. Mary’s Orphans Asylum, Swiss immigration, Texas immigration, The Guide to Texas Emigrants, Galveston 1900 hurricane

Digging History Magazine: Subscription by Check?

Potential Digging History Magazine customers have been asking. “Can I pay by check?” The answer is “Yes” but for subscriptions only. Monthly and Special Edition issues are by Credit Card or PayPal only. Why is that? It would simply be too cumbersome to keep up with monthly individual issue purchases. However, since subscriptions are for a term of your choosing (3-month, 6-month or one-year) it’s a bit easier to accept checks and keep track of customers.

Potential Digging History Magazine customers have been asking. “Can I pay by check?” The answer is “Yes” but for subscriptions only. Monthly and Special Edition issues are by Credit Card or PayPal only. Why is that? It would simply be too cumbersome to keep up with monthly individual issue purchases. However, since subscriptions are for a term of your choosing (3-month, 6-month or one-year) it’s a bit easier to accept checks and keep track of customers.

If you’d like to buy a subscription, but prefer to pay by check, simply send a message on the Contact Page. I’ll contact you and make arrangements for payment by check. Note: Payment via Credit Card or PayPal is preferred because it’s easier to keep track of subscribers, but realize some customers aren’t comfortable making purchases online.

Payment by Credit Card or PayPal (safe and convenient payment gateways) assures you will receive your first issue immediately. Paying by check will delay delivery of your first issue because the check must be mailed and processed before you receive your first issue.

I appreciate your interest in Digging History Magazine and I’m proud to offer it to like-minded lovers of history! Subscriptions are now available. Purchase any subscription level this month (February) and you’ll also receive a free copy of the inaugural January issue.

Sharon Hall, Publisher and Editor, Digging History Magazine

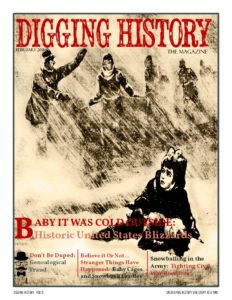

Baby, It Was Cold Outside: Historic United States Blizzards

The word “blizzard”, at least in terms of a violent snowstorm, hasn’t been around as long as one might think. “Blizzard” or “Blizard” are ancient family names, although speculation abounds as to its origin as a surname. One source proposes it may have been a variant of the word “blessed”, perhaps even a nickname.

The word “blizzard”, at least in terms of a violent snowstorm, hasn’t been around as long as one might think. “Blizzard” or “Blizard” are ancient family names, although speculation abounds as to its origin as a surname. One source proposes it may have been a variant of the word “blessed”, perhaps even a nickname.

Two instances in Olde English (”blieths”) and Middle English (”blisse”) mean joy and gladness, and by adding the French suffix “-ard” a term emerges which means a person with those particular qualities. It is only a theory, however.

The word “blizzard” came into usage in America, perhaps in the early nineteenth century, but not as a reference to a snow storm. Colonel David “Davy” Crockett used the term in a memoir of his tour to the “North and Down East”. At Delaware City he boarded a steamboat to Philadelphia and at dinner with his fellow passengers was called upon to offer a toast. Not knowing the sort of people he was dining with, nor what they thought of him personally, he wrote:

. . . . .

The Washington and Jefferson Snow Storm of 1772

This historic storm, called the Washington and Jefferson Snow Storm of 1772, was one of the largest snow storms to ever hit the northern Virginia and Washington, D.C. area . At the time, George Washington and Thomas Jefferson were prominent landowners and both were interested in the weather and how it affected their agricultural interests. We know this because both future presidents recorded weather details in their personal diaries.

. . . . .

The School Children’s Blizzard

This epic storm is reminiscent of an episode of Little House On The Prairie, entitled “Blizzard”. It may well have been based on the 1888 storm which came to be called “The School Children’s Blizzard” or the “School House Blizzard.”

On January 12, 1888 the weather had cleared after a late December-early January storm system dropped massive amounts of snow across the northern and central plains, which was then followed by a four-day cold blast of extremely low temperatures. Between January 11 and the early morning of January 12, many places saw temperatures rise dramatically, twenty to forty degrees.

The temperatures had risen in advance of a significant Arctic cold front being fed by Gulf of Mexico moisture. Many had been home-bound for days because of the snow, ice and brutally cold temperatures. The “balminess” of January 12 lured people out of their homes – little did they realize how quickly the weather was about to change.

, , , , , ,

1913: The Year of Epic Weather Disasters

From beginning to end, the year 1913 was a meteorologically-challenging year. In 1912 the Mississippi River had flooded, killing two hundred people and causing $45 million in damages.

1913 would bring even more catastrophic weather events with extremes from epic blizzards to rain in near “biblical proportions” to scorching summer heat. On July 10, 1913 the highest temperature ever recorded in the United States occurred in Death Valley (134 degrees!).

. . . . . These are but a few snippets of the feature article on historic United States Blizzards. To read the entire article (complete with footnotes and sources), purchase the February issue of Digging History Magazine ($3.99). A few sample pages are available for download at this link if you’d like to see the entire table of contents. This issue features several articles, most related to snow in some way — amazing how much history one can find about snow, blizzards and such — baby cages and snowbank cradles, the ghost town of Snowball, Arkansas, Civil War snowball fights and more. An information-packed 52-page issue which includes a bibliography and a special supplement relating to an article about genealogical fraud.

Keywords: The Big Die-Up, The Great White Hurricane, Children’s Blizzard, Washington and Jefferson Snow Storm of 1772, Great Blizzard of 1888, Knickerbocker Theater Disaster, Great Appalachian Storm of 1950, Washed Way by Geoff Williams, David Laskin, School Children’s Blizzard, Davy Crockett, blizzard, historic blizzards, Blizzard surname, Snowball Arkansas, Ghost Towns, baby cages, snowbank cradles, genealogical fraud, Gustave Anjou, Fighting Civil War Boredom, Civil War snowball fights, 1913 weather events

Digging History Magazine: February 2018

The February issue of Digging History Magazine has been posted and is available for purchase here: February 2018

The February issue of Digging History Magazine has been posted and is available for purchase here: February 2018

It’s winter and it’s all (mostly) about snow. Who knew snow had so much history — 52 pages packed with lots of history, footnotes and sources and a special supplement!

- Baby, It Was Cold Outside: Historic United States Blizzards

- Believe it or not . . . strangers things have happened: Baby Cages and Snowbank Cradles

- Don’t be Duped: Genealogical Fraud

- What’s in a (Sur)name? . . . “Snowy Surnames” and Snow Ships

- Ghost Towns: Snowball, Arkansas

- The Dash: Isaac Lafayette and Arabazena Ottalee Castleberry . . . and more!

The Early American Faith special edition is available for $5.99.

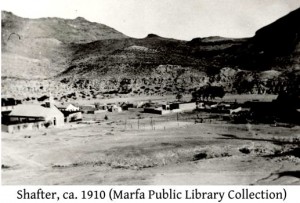

Ghost Town Wednesday: Shafter, The Silver Capital of Texas

This area of Texas is home to just a handful of residents these days, but once boasted a population of four thousand. The town was named for Colonel (later General) William R. Shafter, commander at Fort Davis, and located about eighteen miles north of Presidio. It became a mining town after rancher John W. Spencer found silver ore there in September 1880.

This area of Texas is home to just a handful of residents these days, but once boasted a population of four thousand. The town was named for Colonel (later General) William R. Shafter, commander at Fort Davis, and located about eighteen miles north of Presidio. It became a mining town after rancher John W. Spencer found silver ore there in September 1880.

Shafter had the sample assayed and found it contained enough silver to make it profitable to mine – profitable enough for Shafter himself to invest. Spencer had thought it prudent to share his secret with Shafter since the area was prone to periodic Indian attacks. Protection would be needed to carry out successful mining operations.

Shafter called upon two of his military associates, Lieutenants John L. Bullis and Louis Wilhelmi to join his venture (and clear the area of unfriendlies). The following month Shafter and his partners asked the state of Texas to sell them nine sections of school land in the Chinati Mountains. Eventually only four sections were purchased, but lacking capital the partners leased part of their acreage to a California mining group. Shafter later obtained financial backing in San Francisco and the Presidio Mining Company was organized in the summer of 1883.

Shafter called upon two of his military associates, Lieutenants John L. Bullis and Louis Wilhelmi to join his venture (and clear the area of unfriendlies). The following month Shafter and his partners asked the state of Texas to sell them nine sections of school land in the Chinati Mountains. Eventually only four sections were purchased, but lacking capital the partners leased part of their acreage to a California mining group. Shafter later obtained financial backing in San Francisco and the Presidio Mining Company was organized in the summer of 1883.

The company contracted with Shafter, Wilhelmi and Spencer individually to purchase their interests, each receiving five thousand shares of stock and $1,600 cash. Bullis had purchased two sections in his wife’s name, but when the company’s manager William Noyes found deposits on the Bullis acreage (valued at $45 per ton), a dispute arose. Bullis claimed the two sections had been purchased outright by his wife with inherited funds and not part of the partnership. An injunction was filed to halt mining in that section until the spring of 1884 when operations resumed.

The town of Shafter, situated on Cibolo Creek at the east end of the Chinati Mountains, grew up around the mining operations and a post office was established in 1885, this despite the fact supplies and other resources were hard to come by given its remote location. After legal wrangling over the Bullis sections was concluded, Noyes hired around three hundred men.

Mexicans from both sides of the border, as well as African-Americans, were hired and paid well, and until the Alaska gold rush in 1897 California miners also worked the Presidio Mine. Just like mining towns across the West, miners lived in company housing, shopped at the company store and were treated by the company doctor.

By the turn of the century the town’s population was growing with two saloons, a dance hall, church and a school. A wood-cutting firm was contracted to provide fuel for the furnaces, but by 1910 the wood was exhausted and oil from Marfa was trucked in. Silver pockets were found at around seven hundred feet, some yielding as much as five hundred dollars per ton of ore. By 1913 mules had been replaced by a tram to haul the ore out.

Not long after the town was founded, Texas Rangers were called upon to handle sporadic violence. Then came 1914 – the Mexican Revolution and Pancho Villa – and cause for increased vigilance. Although the mine closed and reopened several times in the 1920’s and 1930’s and the Presidio Mining Company sold out to the American Metal Company in 1928, operations continued unchanged. However, in the throes of the Great Depression, silver prices in 1931 had dropped to twenty-five cents an ounce.

At one time the town’s population had grown to four thousand and employed five hundred miners, but by the early 1930’s had fallen to around three hundred. President Roosevelt’s economic initiatives had brought about some relief, but the mine closed again in 1942. In 1943, no longer strictly a mining town, Shafter had a population of fifteen hundred. Two nearby military bases, the Marfa Army Air Field and Fort D.A. Russell, were served by the twelve remaining businesses.

When the military bases closed following the end of World War II, the town rapidly declined to less than one hundred residents. In 1954 the Anaconda Lead and Silver Company sent surveyors and prospectors, raising the hopes of locals that mining operations at some level would resume. However, Anaconda left and never return despite finding deposits of high grade lead and silver.

Other attempts to revive and sustain mining operations have been made over the years, the most recent when Aurcana Corporation acquired the Shafter mine in 2008. The company spent a considerable amount of money on equipment and hiring, but by 2013 had scaled back considerably and by year’s end had notified 170 employees of a “permanent layoff”.1

Between 1883 and 1942 the mines yielded 30,290,556 troy ounces of silver, 8,389,526 pounds of lead, and 5,981 troy ounces of gold. With severe water shortages in the region, it seems unlikely the mines could ever again be profitably and responsibly operated. The few remaining residents of the area are served by the Marfa school district about thirty-five miles away. The Cibolo Creek Ranch, located between Marfa and Shafter, was where Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia recently died.

If you’d like to see pictures of the area and what remains of the town, maps and various other historic memorabilia, go to Portal to Texas History and type “Shafter” in the search box. Other sources for this article include: Texas State Historical Association and Ghost Towns of the West, by Lambert Florin, 1973, pp. 667-671. Other articles here at Digging History about this area include: Ghost Town Wednesday: Glenn Springs, Texas and two Tombstone Tuesday articles about a bit of Texas history relating to the Pancho Villa era here and here.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Far-Out Friday: Death By Pimple

I ran across this intriguing subject while researching an early Surname Saturday article about the Pimple surname. I found several references to so-called “death by pimple” and researched further. Clearly, the problem was due to lack of an effective way to treat infection prior to the late 1920’s and early 1930’s.

That’s not to say doctors didn’t try to treat infections. There were advertisements galore during the nineteenth century hailing various “miracle cures” for all sorts of maladies, pimples included. The first instance found in a search of “pimple” at Newspapers.com yielded an article about a suspect in the disappearance of a surgeon who “hath been set upon by some ill people.”

That’s not to say doctors didn’t try to treat infections. There were advertisements galore during the nineteenth century hailing various “miracle cures” for all sorts of maladies, pimples included. The first instance found in a search of “pimple” at Newspapers.com yielded an article about a suspect in the disappearance of a surgeon who “hath been set upon by some ill people.”

This article will be included in the March-April 2020 issue of our digital publication — Digging History Magazine. The magazine article, entitled “Ways to Go in Days of Old”, will explore the numerous (and sometimes tragic) ways our ancestors met their demise.

This article will be included in the March-April 2020 issue of our digital publication — Digging History Magazine. The magazine article, entitled “Ways to Go in Days of Old”, will explore the numerous (and sometimes tragic) ways our ancestors met their demise.

Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads, just carefully-researched stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue (or two)? Go to the free sample page and download either or both of January-February 2019 or March-April 2019 issues. Totally free for you to enjoy and decide whether you’d like to become a magazine subscriber.

Thanks for stopping by!

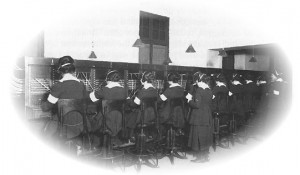

Military History Monday: Hello Girls of World War I

During World War I they were officially known as the Signal Corps Female Telephone Operators Unit, but more informally known as “Hello Girls”. The United States had been reluctant to join its European allies in the conflict, but when Germany began an all-out effort in early 1917 to sink American vessels in the North Atlantic, President Woodrow Wilson’s hand was forced. He asked Congress for a declaration of war, “a war to end all wars”. On April 6, 1917 Congress officially did so, engaging the Germans and hoping to make the world once again safe for democracy.

During World War I they were officially known as the Signal Corps Female Telephone Operators Unit, but more informally known as “Hello Girls”. The United States had been reluctant to join its European allies in the conflict, but when Germany began an all-out effort in early 1917 to sink American vessels in the North Atlantic, President Woodrow Wilson’s hand was forced. He asked Congress for a declaration of war, “a war to end all wars”. On April 6, 1917 Congress officially did so, engaging the Germans and hoping to make the world once again safe for democracy.

The British had been at war with German for nearly three years when the United States joined the effort. With their men away fighting the war, large numbers of women were working in munitions factories throughout Britain. Their work was dangerous as explosives and chemicals caused deaths. The greatest single loss occurred in early January 1917 when a munitions factory in Silvertown, England exploded due to an accidental fire – seventy-two women were severely injured and sixty-nine perished.

The British had been at war with German for nearly three years when the United States joined the effort. With their men away fighting the war, large numbers of women were working in munitions factories throughout Britain. Their work was dangerous as explosives and chemicals caused deaths. The greatest single loss occurred in early January 1917 when a munitions factory in Silvertown, England exploded due to an accidental fire – seventy-two women were severely injured and sixty-nine perished.

This article is no longer available for free at this site. It was re-written and enhanced, complete with footnotes and sources and has been published in the November 2018 issue of Digging History Magazine. This particular issues featured articles about World War I, including how to find genealogical records. Should you prefer to purchase the article only, contact me for more information.

This article is no longer available for free at this site. It was re-written and enhanced, complete with footnotes and sources and has been published in the November 2018 issue of Digging History Magazine. This particular issues featured articles about World War I, including how to find genealogical records. Should you prefer to purchase the article only, contact me for more information.

I invite you to check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Feisty Females: Sara Payson Willis, aka Fanny Fern

March is Women’s History Month and what better way to kick it off than to highlight the accomplishments of first female newspaper columnist and highest paid nineteenth century newspaper writer Sara Payson Willis, a.k.a. “Fanny Fern”.

March is Women’s History Month and what better way to kick it off than to highlight the accomplishments of first female newspaper columnist and highest paid nineteenth century newspaper writer Sara Payson Willis, a.k.a. “Fanny Fern”.

Sara was born in Portland, Maine on July 9, 1811, the daughter of Nathaniel and Hannah (Parker) Willis. Her parents had planned to name their fifth child after Reverend Edward Payson, pastor of Portland’s Second Congregational Church (five years later they named a son after the reverend). Instead, she was given the middle name of Payson.

Six weeks following her birth Nathaniel moved his family to Boston where he founded the first religious newspaper published in the United States, The Puritan Recorder. As a deacon at Park Street Church and a strict Calvinist, Nathaniel frowned on dancing and other ungodly pursuits and worried about the soul of his free-spirited daughter Sara. Hannah, however, was the polar opposite of her husband and the parent Sara most identified with.

Six weeks following her birth Nathaniel moved his family to Boston where he founded the first religious newspaper published in the United States, The Puritan Recorder. As a deacon at Park Street Church and a strict Calvinist, Nathaniel frowned on dancing and other ungodly pursuits and worried about the soul of his free-spirited daughter Sara. Hannah, however, was the polar opposite of her husband and the parent Sara most identified with.

Her older brother Nathaniel Parker Willis experienced his own religious conversion at the age of fifteen, but after his rising success as a poet resulted in his being excommunicated from the Congregational Church, the elder Willis was more determined to see Sara embrace his faith as her own, sending her to Catherine Beecher’s Female Seminary in Hartford, Connecticut.

Sara, however, had no intention of conforming to her father’s strict faith. Years later Catherine Beecher would tell Sara she remembered her as the worst behaved child in the school – and the best loved! Harriet Beecher Stowe, a pupil-teacher at her sister’s school, remembered Sara as a “bright, laughing witch of a half saint half sinner.”2

While Sara struggled with arithmetic, she excelled in writing. Her compositions, full of satire and clever wordplay, were sought after by the editor of the local newspaper. After returning to Boston in 1830 or 1831 she edited and wrote articles for her father’s publications, The Recorder and The Youth’s Companion, without remuneration and not a thought of someday making a career of her talents as a writer.

In 1837 Sara married Charles Harrington Eldredge and together they had three daughters: Mary (1838); Grace (1841) and Ellen (1844). The first seven years of their marriage were happy and fulfilling until a series of tragedies changed the trajectory of Sara’s life forever. In February of 1844 her sister Ellen died from complications of childbirth. When Hannah died six weeks following Ellen’s death it created a life-long void for Sara. Sara had always had a special bond with Hannah, they being of similar temperaments.

One year later and six months following her youngest daughter Ellen’s birth, Mary died of brain fever. Still more tragedy awaited Sara as Charles contracted typhoid fever and passed away in 1846. Charles had been involved in a lawsuit (which he lost) and after all accounts were settled, Sara found herself destitute without means to support herself and her two remaining daughters.

Nathaniel Willis provided a small portion of Sara’s support following Charles’ death, although he resented his son-in-law having been such a poor steward of his finances. The Eldredge family blamed their daughter-in-law, yet also reluctantly agreed to provide some support as well. Still, Nathaniel (who had soon remarried himself following Hannah’s death) urged his daughter to remarry.

Sara capitulated and entered into an admittedly loveless marriage with Samuel P. Farrington, a widower, on January 15, 1849. Not surprising, it turned out to be a terrible mistake as Farrington relentlessly criticized her for just about everything – from her appearance to her friends to the memory of Charles. Although she tried to be a good parent to his children, Farrington used them to spy on their stepmother.

In January 1851 Sara reached her breaking point, and to the consternation of her family, contacted a lawyer and moved into a hotel with Grace and Ellen. Farrington publicly disparaged her, left Boston and later obtained a divorce in Chicago claiming desertion by his wife. Nathaniel was none too happy with the turn of events and refused to resume support.

Sara struggled for several months, working jobs too menial to allow her to put food on the table and adequately provide for her children. Grace was sent to live with her Eldredge grandparents while Ellen remained with her mother, both barely subsisting on bread and milk. In November of 1851 Sara decided to try her hand at writing again and published her first article in the Olive Branch, a new Boston newspaper. The article, entitled “The Governess” was soon followed up by short satirical articles in other publications under the pen name of “Fanny Fern”.

She sent articles to her brother Nathaniel, by then a magazine publisher. He turned her down, believing her irreverent writings to have little appeal outside of Boston. Nathaniel couldn’t have been more wrong as newspapers and periodicals began carrying the witty and irreverent columns of Fanny Fern. By the summer of 1852 she had been hired by publisher Oliver Dyer, becoming the first woman to have a regular column in a newspaper and doubling her previous salary. Little did Dyer know that one of his editors was Sara’s brother Richard, a musician and journalist who wrote the melody for It Came Upon a Midnight Clear.

Meanwhile, James Parton, Fanny Fern admirer and Nathaniel’s editor, had been clipping her articles and like other publications had been pirating them. Nathaniel demanded his editor stop clipping the articles but Parton refused and subsequently resigned.

Early in 1853 the publishing firm of Derby and Miller contacted Sara through her Fanny Fern column, offering to publish a book of her newspaper articles. She was offered the choice of payment by royalty of ten cents per book or one thousand dollars and an outright purchase of the copyright. Sara chose the royalty and was handsomely rewarded as the book, entitled Fern Leaves From Fanny’s Portfolio, sold seventy thousand copies in the United States in less than a year. Another twenty-nine thousand copies sold in England.

With a much improved financial outlook, Sara was able to take back Grace from the Eldredges and moved to New York. She secured a regular column in the New York Ledger at a salary of $100 per week, then the highest salary of any columnist, male or female, in the country. The column appeared each week until her death in 1872.

Under her pen name she began to write novels, first publishing Ruth Hall, a fictional work based on her own life story, in 1854. The book depicted her happy first marriage followed by poverty and included some less-than-flattering “payback” for her disparaging and disapproving relatives. After her actual name was publicized some critics expressed disdain for her scathing portrayal of family members. Nathaniel Hawthorne, however, wasn’t among her critics – rather, he quite enjoyed her style of writing.

Nevertheless, Sara took note of the criticism and set a different tone in her second autobiographical novel, Rose Clark. Never shy about her opinions nor immune to controversy, Fanny Fern defended Walt Whitman’s controversial work, Leaves of Grass, in May of 1856. She had this to say about herself, her critics and the city she left behind:

And here by the rood, comes Fanny Fern! Fanny is a woman. For that she is not to blame; tho’ since she first found it out, she has not ceased to deplore it. She might be prettier, she might be younger. She might be older and she might be uglier. She might be better and she might be worse. She has been both over-praised and over-abused, and those who have abused her worst have imitated and copied her most. One thing may be said in favor of Fanny: She was not, thank Providence, born in the beautiful, backbiting sanctimonious, slandering, clean, contumelious, pharasaical, phiddle-de-dee, peck-measure city – of Boston.3

At the age of forty-five Sara married her long-time admirer James Parton, living in New York City and later raising her granddaughter Ethel following Grace’s death in 1862. In 1859 she purchased a Manhattan brownstone as she continued to write for the Ledger. As a long-time supporter of the women’s suffrage movement, Sara co-founded Sorosis, following criticism directed at New York City’s all-male Press Club. Sorosis was America’s first professional club for women.

Sara Payson Willis died on October 10, 1872 following a six-year battle with cancer. Her close friends never knew she was ill until near the end of her life. After losing the use of her right hand she began writing her weekly column with the left. When that became impossible she dictated her column to Ellen or James, never missing a single column until the last one was published two days after her death.

She bucked the conventional Victorian ideas of how a lady was expected to conduct herself. Despite criticism of her unconventional and sometimes-coarse personality and writing style, her success as a writer proved that women could indeed make it in a man’s world. Sara knew that if a woman could achieve financial independence it was entirely possible that someday all women would achieve full and equal rights. How right she was.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!