Ghost Town Wednesday: Coolidge, Montana

The Elkhorn-Coolidge Historic District is located in the northern part of Beaverhead County, Montana and south of Butte. In 1872 silver was first discovered by Preston Sheldon, and his first shipment of ore yielded 300 ounces per ton. He supposedly named the mine “Old Elkhorn” after finding a pair of elkhorns near the site. In 1874, Mike Steele discovered the Storm Claim just west of the Old Elkhorn, his ore find yielding 260 ounces per ton. Other veins were discovered and increasingly more miners arrived.

The Elkhorn-Coolidge Historic District is located in the northern part of Beaverhead County, Montana and south of Butte. In 1872 silver was first discovered by Preston Sheldon, and his first shipment of ore yielded 300 ounces per ton. He supposedly named the mine “Old Elkhorn” after finding a pair of elkhorns near the site. In 1874, Mike Steele discovered the Storm Claim just west of the Old Elkhorn, his ore find yielding 260 ounces per ton. Other veins were discovered and increasingly more miners arrived.

Although there was plenty of silver to be mined, operations were restricted due to a lack of affordable transportation. The process of smelting was quite expensive – first the ore was hauled by animal teams to Corrine, Utah to be loaded on railroad cars headed for San Francisco. From San Francisco the ore was loaded on ships headed to Swansea, Wales where the smelting process would take place. Even with that long and arduous process of mining, transportation and smelting, miners still managed to eke out a small profit.

Although there was plenty of silver to be mined, operations were restricted due to a lack of affordable transportation. The process of smelting was quite expensive – first the ore was hauled by animal teams to Corrine, Utah to be loaded on railroad cars headed for San Francisco. From San Francisco the ore was loaded on ships headed to Swansea, Wales where the smelting process would take place. Even with that long and arduous process of mining, transportation and smelting, miners still managed to eke out a small profit.

In the 1880’s profitability improved with the construction of the Utah and Northern Railway to Silver Bow (Montana) which was completed at the end of 1881. In 1893, however, the silver market crashed and all mines were closed for ten years. In 1903 mining activity was revived in the area but still struggled due to problems with financing the operations.

In 1911 a former Montana Lieutenant Governor, William R. Allen, began buying claims in the area and in 1913 established the Boston-Montana Development Corporation. Allen had resigned his position as Lieutenant Governor to devote all his efforts toward the revival of silver mining in the Elkhorn District. The Boston-Montana Mining and Power Company was established to further develop the mines and to construct a mill and small railroad line. In 1914 the town of Coolidge was established, named after Allen’s friend Calvin Coolidge, he being the Lieutenant Governor of Massachusetts at that time and future President of the United States.

A wagon road was built but a rail line would make the task of transporting the ore much more efficient. Plans were laid out and some machinery was purchased, but financial backing was scarce with the outbreak of World War I. Construction of the railroad finally began in May of 1917 and completed in late 1919. The line was 38 miles long and ran along the Big Hole River from Divide up to Wise River and from there south to the Pioneer Mountains and into Coolidge. It was possibly the last narrow gauge railroad to be built in the country.

With the railroad operational, heavy equipment and machinery for the mill could more easily be transported. Work on the mill was begun and also a 65,000 volt power line that would stretch from Divide to the mine and Coolidge. The mill cost approximately $900,000 to complete and the power line $150,000 – at the time it was the largest mill in Montana.

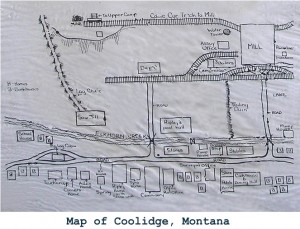

The town of Coolidge sprung up alongside the mining and mill operations. Although it was named after Calvin Coolidge, he never visited the area, although some believe he may have invested in the mining operations. At first there weren’t many permanent structures and miners lived in tents. Later the town began to be populated with buildings common for “company towns” of that day. A company store sold food, supplies and equipment to the miners and a boarding house provided meals. There was a pool hall, but no saloons. However, liquor was said to be obtainable from a still outside of town.

The company offices and living quarters for the miners were also built. Electricity and telephone service were provided, but plumbing was a bit primitive with few facilities for bathing. One of William Allen’s daughters, Elizabeth Patterson, lived in Coolidge when she was young and related that residents would trek up to the mill for a shower. There were no churches in Coolidge, and probably at the peak of its existence was home to about 350 residents.

A school was established in 1918 and the post office was in operation from 1922 to 1932. In the early 1930’s the population began to decline so the school and post office closed. Most of the mining development project had been completed by 1922, and approximately five million dollars had been poured into the project. However, the financial dominoes began to fall. In 1920-1921 there was a recession and the company’s bond and note issues were starting to come due. Also it had been discovered, after all the work and money put into development, that the projections for ore to be taken out of the mine were underestimated. The company was forced to mine lower-grade ore as well but the math just didn’t add up.

In 1927 the Wise River Dam burst and flooded out several miles of track and bridges. By 1930 the repairs were completed, but by then, of course, the Great Depression was having a huge impact on the country. By 1932, much of the town of Coolidge was abandoned. In 1933 the company was reorganized and through the years changed hands several times. The Elkhorn Mines had literally cost William Allen a fortune, but he continued to try and find other investors until 1953.

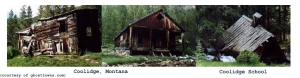

The town site of Coolidge is located south of Butte and a few dilapidated buildings remain. The mill remains are not accessible, however.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Tombstone Tuesday: Leo Leroy and Pansy Mae (Willey) Hagel – Briston, Montana

Leo Leroy and Pansy Mae (Willey) Hagel, husband and wife, are buried in the Briston Cemetery in Beaverhead County, Montana – near the area called Big Hole. They were born in different places and their families made their way to Montana in the late 1890’s for different reasons.

Leo Leroy Hagel

Leo Leroy Hagel was born on January 21, 1888 in Limestone, Peoria County, Illinois to parents Franklin Charles and Matilda (Harris) Hagel, their second oldest child of ten. Leo’s father was a Doctor of Osteopathy as noted in the Lewis County, Idaho telephone directory in 1912 and various census records. The 1900 census referred to Frank as a “Magnetic Healer” – the practice of magnetic healing being a forerunner to chiropractic medicine.

Leo’s family was of German ancestry – his paternal grandparents were born in Prussia (grandfather) and Bavaria (grandmother). The Hagel family migrated to Salmon, Idaho (eastern Idaho, near the Montana border) in approximately 1894.

In 1907, Leo made his first trek over Big Hole Pass, a Continental Divide pass crossed over by Lewis & Clarke in 1805 or 1806. On the other side of the pass was the town of Briston, where he would meet Pansy Mae Willey and marry her on November 10, 1912.

According to family history, Leo trapped “red fox, weasel, skunks, coyotes and anything else he could get a dollar out of. His favorite fur-bearer was the pine marten.” Leo lived in Gibbonsville, Lemhi County, Idaho and worked as a gold miner, perhaps with his older brother Elmer (also a gold miner), according to the 1920 census. It was unlikely that their gold mining work produced much income, however. The Gibbonsville mine, although it had produced a considerable amount of gold, was beginning to play out by the early 1900’s. After a 1907 fire, official company mining operations ceased, although sporadic mining continued for a time.

According to family history, Leo trapped “red fox, weasel, skunks, coyotes and anything else he could get a dollar out of. His favorite fur-bearer was the pine marten.” Leo lived in Gibbonsville, Lemhi County, Idaho and worked as a gold miner, perhaps with his older brother Elmer (also a gold miner), according to the 1920 census. It was unlikely that their gold mining work produced much income, however. The Gibbonsville mine, although it had produced a considerable amount of gold, was beginning to play out by the early 1900’s. After a 1907 fire, official company mining operations ceased, although sporadic mining continued for a time.

In 1930 Leo and Pansy were living in the Noble precinct of Lemhi County and Leo was a farmer. In 1940 they continued to farm in the Gibbonsville precinct, with Leo at age 52 working 72 hours per week. Pansy, alongside him, put in the same amount of hours as a “laborer”. In 1940 the census, for the first time, enumerates information regarding levels of education – Leo had a fifth grade education and Pansy and eighth grade education.

Pansy died at the age of 59 in 1952, just a month short of her 60th birthday. Leo married Ruth Frederickson Schlagel, a widow, on February 11, 1954 at the age of 66. At the time of his death on July 18, 1986, Leo was residing in North Fork, Lemhi, Idaho, but according to death records he died in Missoula, Montana.

Pansy Mae Willey Hagel

Pansy Mae Willey was born on September 30, 1892 in Glidden, Iowa to parents Thomas Henry and Sophia Butterworth Pendleton Willey. Her mother had been born in England in 1849 and immigrated to America in 1850. Both of Thomas’ parents were born in England and he was born in Wisconsin in 1849.

Thomas, a farmer and cheese maker, died on February 23, 1895, leaving Sophie with six children to care for. According to family history, some cousins in Mississippi offered to help and Pansy’s brother Asa (age 13) piloted a flatboat down the Mississippi River with the family’s livestock on board. The rest of the family joined him and they remained there for approximately four years.

Their cousin, Frank Pendleton, visited them in 1898. He had a ranch in the Big Hole Valley in Montana and convinced Asa to come for a visit. At age 18 Asa left for Big Hole and settled in Wisdom. When the rest of his family joined him in Montana, they settled in Briston, where Pansy and Leo met.

After their marriage, Leo and Pansy had a child, Arlo, who was born on June 14, 1914. Sadly, Arlo died on January 2, 1917 – perhaps a victim of the flu pandemic. Leo and Pansy never had any more children.

On August 30, 1952 Pansy died and was buried in the Briston Cemetery in Beaverhead County, Montana. Years later, in 1986, Leo was buried next to her.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Military History Monday: The Battle of Big Hole (Montana)

In 1805, Lewis and Clark named them “Nez Perce”, which literally means “pierced nose”, except this tribe didn’t perform nose piercings – that was the Chinook tribe. The tribe’s name was actually “Nimi’puu” (Nee-Me-Poo) and meant “the people” or “we the people”. This tribe was indigenous to a vast area of land (17 million acres) which covered present day Washington, Oregon, Idaho and Montana. Rather than being one distinct tribe, this group actually consisted of various bands with somewhat different languages, managing to live together peacefully – the tribes (Shoshonis, Bannack and Blackfoot) to the south were not quite so friendly, however.

In 1805, Lewis and Clark named them “Nez Perce”, which literally means “pierced nose”, except this tribe didn’t perform nose piercings – that was the Chinook tribe. The tribe’s name was actually “Nimi’puu” (Nee-Me-Poo) and meant “the people” or “we the people”. This tribe was indigenous to a vast area of land (17 million acres) which covered present day Washington, Oregon, Idaho and Montana. Rather than being one distinct tribe, this group actually consisted of various bands with somewhat different languages, managing to live together peacefully – the tribes (Shoshonis, Bannack and Blackfoot) to the south were not quite so friendly, however.

The Nez Perce acquired horses sometime in the mid-1700’s, becoming expert horseman, and by the nineteenth century were the largest owner of horses in North America. They were a nomadic tribe, moving with the seasons to fish, hunt and gather – salmon, deer, elk, berries, pine nuts, sunflower seeds, wild potatoes and carrots.

The Nez Perce acquired horses sometime in the mid-1700’s, becoming expert horseman, and by the nineteenth century were the largest owner of horses in North America. They were a nomadic tribe, moving with the seasons to fish, hunt and gather – salmon, deer, elk, berries, pine nuts, sunflower seeds, wild potatoes and carrots.

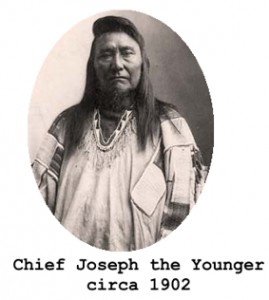

Two of the most prominent tribal leaders were Chief Joseph the Elder and Chief Joseph the Younger. The elder had taken the Christian name of “Joseph” when he converted to Christianity and was baptized at the Lapwai mission in 1838. His son was born in 1840 and given the name “Hin-mah-too-yah-lat-kekt” or “Thunder Rolling Down the Mountain”, but became known as “Joseph the Younger”.

Joseph the Elder promoted peace with the white man, signing a treaty with the United States government in 1853 which set up a large reservation spanning across Oregon and into Idaho. When the gold rush brought more white settlers, in 1863 the government took more land and relegated the tribe to an area of land in Idaho which was one-tenth the size of the original allocation. At this point, Joseph the Elder denounced the United States government, destroyed the American flag and his Bible, refused to move his people to the Wallowa Valley and refused to sign another treaty. One faction of the tribe, headed by the Head Chief Lawyer and others decided to honor the treaty, and thus the tribe was split.

Joseph the Elder promoted peace with the white man, signing a treaty with the United States government in 1853 which set up a large reservation spanning across Oregon and into Idaho. When the gold rush brought more white settlers, in 1863 the government took more land and relegated the tribe to an area of land in Idaho which was one-tenth the size of the original allocation. At this point, Joseph the Elder denounced the United States government, destroyed the American flag and his Bible, refused to move his people to the Wallowa Valley and refused to sign another treaty. One faction of the tribe, headed by the Head Chief Lawyer and others decided to honor the treaty, and thus the tribe was split.

When Joseph the Elder died in 1871, leadership passed to Joseph the Younger. Like his father before him, Joseph refused to cede the land originally given to the tribe in 1853. Through negotiations and debates with the federal government, Joseph elevated his stature as a statesman, however. In 1873, it appeared that his efforts had been successful in allowing his people to remain, but the government reversed itself and beginning in 1877 threats of military enforcement and engagement were circulated.

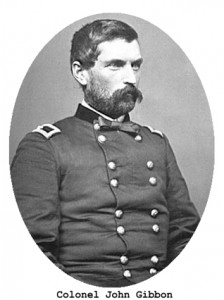

Chief Joseph began to sense that he would not succeed and decided to lead his people towards Canada. His band of warriors fought a series of skirmishes and four major battles along the way – the third was called the Battle of Big Hole. Major General John Gibbon had served in the Mexican-American War and the Civil War. After the Civil War he continued to serve, but reverted to the rank of Colonel while commanding the infantry based at Fort Ellis in Montana Territory.

Colonel Gibbon received a telegram from General Oliver Howard directing him to cut off the fleeing Nez Perce. On his way to intercept and attack the Nez Perce, he was joined by forty-five citizens who believed that the Indians should be punished. Gibbon and his troops were averaging thirty to thirty-five miles per day and estimated that for every day the Nez Perce traveled, they were traveling the equivalent of two, so it was only a matter of time until they caught up to them. Along the route they gathered information – there were still at least 400 warriors and approximately 150 women and children, in addition to 2,000 horses and plenty of guns and ammunition.

Colonel Gibbon received a telegram from General Oliver Howard directing him to cut off the fleeing Nez Perce. On his way to intercept and attack the Nez Perce, he was joined by forty-five citizens who believed that the Indians should be punished. Gibbon and his troops were averaging thirty to thirty-five miles per day and estimated that for every day the Nez Perce traveled, they were traveling the equivalent of two, so it was only a matter of time until they caught up to them. Along the route they gathered information – there were still at least 400 warriors and approximately 150 women and children, in addition to 2,000 horses and plenty of guns and ammunition.

When some of the citizen troops wanted to turn back to attend to affairs at home, Gibbons implored them to continue knowing that without them they would likely be outnumbered. After a promise that any horses captured would be equally divided among them, the citizens enthusiastically agreed to continue. The Colonel then sent Lieutenant James H. Bradley, who was joined by Lieutenant J.W. Jacobs, to take their troops and strike the Nez Perce camp before daylight the next day. They thought if they were able to stampede the stock the Indians would begin to disperse and victory would be certain.

However, the trail proved to be more difficult than anticipated and they were unable to reach the camp before daylight. Consequently, the Indians had broken camp and traveled on – but their journey that day was short and they again encamped at the mouth of Trail Creek. Lt. Bradley would then conceal his troops in the hills and await the arrival of the infantry. Gibbons pressed on through the day and arrived at Bradley’s camp around sundown. He was then informed by Bradley that it was likely the Nez Perce would remain at that camp for several days since the women were seen cutting and peeling lodge poles to erect shelter.

Before Colonel Gibbon’s arrival, Bradley had sent out men to ascertain the exact position of the camp and its activities. Gibbon took a nap and at 10:00 p.m. he was awakened to begin preparations for the troops to move as quickly and quietly as possible to the encampment. After five miles without detection, the troops reached an area which opened up into the valley of the Big Hole River. They could see smoldering camp fires in the distance and were able to proceed to within a few hundred yards of the quiet, sleeping camp.

The troops encountered a group of horses and Gibbon was cautioned that if they tried to move the animals out they might lose the element of surprise. If he had known there was in fact no one guarding the horses that night, the Indians would have been placed in an extremely vulnerable situation, all without the Army firing a shot. By 2:00 a.m. on the morning of August 9, 1877, the troops were within approximately 150 yards of the camp, waiting quietly in the cold for stirrings in the camp. Around 3:00 squaws came out of their tents to stoke the waning fires and then returned to their beds.

At dawn the troops began to quietly move again. An Indian had arisen and mounted his horse and headed toward the herd. As he emerged from a thicket of willows, he and his horse were shot. The standing orders were to charge the camp as soon as the first shot was fired. The troops were more than ready and the element of surprise was complete. According to The Battle of the Big Hole by George O. Shield, “squaws yelled, children screamed, dogs barked, horses neighed and snorted, and many of them broke their fetters and fled.”

Even the warriors, usually so stoical, and who always like to appear incapable of fear or excitement, were, for the time being, wild and panic-stricken like the rest. Some of them fled from the tents at first without their guns and had to return later, under a galling fire, and get them. Some of those who had presence of mind enough left to seize their weapons were too badly frightened to use them at first and stampeded, like a flock of sheep, to the brush.

The soldiers shot to kill and “[M]any an Indian was cut down at such short range that his flesh and clothing were burned by the powder from their rifles.” The Indians, however, recovered from the overwhelming surprise and began to fight back. Only twenty minutes had transpired after the first shot was fired when the troops had secured victory – orders were then given to burn the camp, but several Indians had already fled and because of the dampness of the grass from the early morning dew the destruction was not complete.

The death toll was significant for both sides – the Army had lost 29 men with 40 wounded and they counted 89 Nez Perce bodies, mostly women and children. The battle had rendered a major blow, but not a fatal one, as the Indians continued fleeing to the northeast, intent on reaching Canada and a new home.

Two months later troops led by Colonel Nelson Miles again overtook the Nez Perce, decisively defeating them at the Battle of the Bear Paw Mountains. Chief Joseph and his remaining tribe members had traveled to within 40 miles of the Canadian border when he finally gave up saying:

I am tired of fighting. My people ask me for food, and I have none to give. It is cold, and we have no blankets, no wood. My people are starving to death. Where is my little daughter? I do not know. Perhaps even now she is freezing to death. Hear me, my Chiefs, I have fought; but from where the sun now stands, Joseph will fight no more.

The Nez Perce were sent to Kansas and then to Oklahoma Indian Territory, although General Miles had promised they would be allowed to return to their country. Many years later a small band was allowed to return to the Colville Reservation in eastern Washington, however. Chief Joseph was allowed to travel to Washington, D.C. to tell his story and he gave an impassioned speech, which was published in the April 1879 issue of the North American Review:

I only ask of the Government to be treated as all other men are treated. If I cannot go to my own home, let me have a home in some country where my people will not die so fast. I would like to go to Bitter Root Valley. There my people would be healthy; where they are now they are dying. Three have died since I left my camp to come to Washington.

When I think of our condition my heart is heavy. I see men of my race treated as outlaws and driven from country to country, shot down like animals.

I know that my race must change. We can not hold our own with the white men as we are. We only ask an even chance to live as other men live. We ask to be recognized as men. We ask that the same law shall work alike on all men. If the Indian breaks the law, punish him by the law. If the white man breaks the law, punish him also.

Let me be a free man—free to travel, free to stop, free to work, free to trade where I choose, free to choose my own teachers, free to follow the religion of my fathers, free to think and talk and act for myself—and I will obey every law, or submit to the penalty.

Whenever the white man treats the Indian as they treat each other, then we will have no more wars. We shall all be alike—brothers of one father and one mother, with one sky above us and country around us, and one government for all. Then the Great Spirit Chief who rules above will smile upon this land, and send rain to wash out the bloody spots made by brothers’ hands from the face of the earth. For this time the Indian race are waiting and praying. I hope that no more groans of wounded men and women will ever go to the ear of the Great Spirit Chief above, and that all people may be one people.

In-mut-too-yah-lat-lat has spoken for his people.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Surname Saturday: Titcomb

Titcomb is an English surname which referred to someone who came from Tidcombe in Wiltshire. In Old English the name was “Titicome”, or someone who dwelt at a place where birds habitated. In Wiltshire, this family held a seat as “Lords of the Manor of Tidcombe”.

Early records show the name used, but without a surname: “Titicome” in 1086 and “Titecumba” in Wiltshire in 1197 and “Titecumbe” in 1242. William Tittacombe was documented in Somerset County in the 1300’s. By the mid-1400’s, the usage of surnames became more common. Other spelling variations include: Tytcomb, Tidcom, Titcum, Tidcum, Titchcume, Titchcumb, Titchcomb and Tichcomb.

Perhaps the first Titcomb to venture across the ocean to New England is highlighted below, along with one of his descendants, many of whom fought valiantly in the Revolutionary War.

William Tytcombe

William Tytcombe was born on August 6, 1618 in Wiltshire, England to parents Edward and Alice (Coleman) Tytcombe. Young William took passage on the Mary and John with a group of Puritans on March 24, 1634. However, William was one of six men who were left behind to “oversee the chattle” (cattle) which departed Southampton on April 16, 1634. Both ships arrived in late May or early June and most passengers went first to the village of Ipswich in Massachusetts Bay Colony.

A year later the group moved up the coast and founded the town of Newbury. Prior to 1640, William married Joanna Bartlett, daughter of Elder Richard Bartlett, Sr. Their first child, Sarah, was born on February 17, 1640, followed by the birth of several more children:

Hannah – January 3, 1642

Mary – February 17, 1644

Millicent – July 7, 1646 (died January 20, 1664)

William – March 18, 1648 (died June 2, 1659)

Penuel – December 16, 1650

Benaiah – June 28, 1653

Joanna died on the same day that Benaiah was born so she died in childbirth. On March 3, 1654 William married widow Elizabeth (Bitfield) Stevens. To their union were born the following children:

Elizabeth – December 12, 1654

Rebecca – April 1, 1656

Tirzah – February 21, 1658

William(2) – August 14, 1659

Thomas – October 11, 1661

Lydia – June 13, 1663

John – September 11, 1664

Ann – July 7, 1666

William fathered fifteen children, all living to full adulthood with the exception of the first William, Hannah (not mentioned in his 1676 will) and Millicent.

William was a farmer and active in the affairs of both his church and town. On June 22, 1642, he took the oath of freeman, becoming a full-fledged member of the colony. In 1646 he was a selectman, served on various town committees, a commissioner in 1655, 1658 and 1670, a deputy to the General Court in 1655, a constable in 1651, as well as serving as a juror several times.

William was a farmer and active in the affairs of both his church and town. On June 22, 1642, he took the oath of freeman, becoming a full-fledged member of the colony. In 1646 he was a selectman, served on various town committees, a commissioner in 1655, 1658 and 1670, a deputy to the General Court in 1655, a constable in 1651, as well as serving as a juror several times.

William became embroiled in a church controversy beginning in 1645. The faction that William aligned himself with preferred to be governed by elders and a presbytery, rather than the Congregational consent and election method of governance. The controversy continued until in 1671 a trial decision determined that William, along with five others (including his brother-in-law Richard Bartlett) were “guilty of very great misdemeanors, though in different degrees, deserving of severe punishment.” William’s fine was four nobles (coins) – the leader of the opposition was fined twenty nobles.

William died on September 24, 1776. Judge Samuel Sewall noted in his diary that he died “Sabbath day, after about a fortnight’s sickness of the Fever and Ague,” and “one week thereabout lay regardless of any person and in great pain.” His will had been written six days before his death wherein he bequeathed varying amounts of money to eleven of his children. To his wife Elizabeth he left one-third of all his lands for her use and benefit until she died. The remainder of his land and holdings passed to his oldest surviving son, Penuel.

Brigadier General Jonathan Titcomb

The great grandson of William Titcomb was a prominent officer during the Revolutionary War. Jonathan Titcomb was born to Josiah and Martha (Rolf) Titcomb on September 12, 1727 – Josiah was Benaiah’s son. Jonathan was appointed a Brigadier General and “manifested great zeal and activity in his country’s cause throughout the war.” His leadership during the Battle of Rhode Island was noted by Lafayette as “the best fought battle of the war.”

In 1784 he received an appointment from General Washington as a naval officer, and was appointed again in 1790. General Washington visited Newbury in 1790 and Jonathan served as one of his escorts, as noted in Washington’s diary. No doubt, great grandfather William would have been proud.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Tombstone Tuesday: Nancy Crawford Bray (b. 16 Feb 1801 d. 12 Mar 1902)

Nancy Crawford Bray was born on February 16, 1801 in Virginia (possibly Greenbrier, which is now West Virginia). Her mother died when Nancy was but seven years old — family histories and newspaper articles record that she helped raise her three young brothers. Her father, William, moved his family to Ohio in the early 1820’s, possibly 1823.

Nancy Crawford Bray was born on February 16, 1801 in Virginia (possibly Greenbrier, which is now West Virginia). Her mother died when Nancy was but seven years old — family histories and newspaper articles record that she helped raise her three young brothers. Her father, William, moved his family to Ohio in the early 1820’s, possibly 1823.

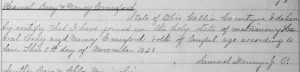

On November 7, 1823, Nancy Crawford married a Baptist minister, Harrell Bray, in Gallia, Ohio. The Justice of the Peace, Samuel Denny, was related to Harrell’s mother, Elizabeth Denny Bray.

The children born to Harrell and Nancy were (as best I can determine, although one source said they had ten children): Elisha, Elizabeth, Louisa, William, Harrell, Jr., Nathaniel, Nancy and Reuben.

According to the 1830 census, the Bray family lived in Starr, Hocking County, Ohio. Census records for 1840 weren’t found but it’s possible the Bray family had already migrated to Dallas County, Missouri. A newspaper story referred to Harrell Bray participating in the 1841 founding of Buffalo, Missouri (county seat). He helped survey the town site and Nancy prepared meals for the camp (referring to Nancy as an “energetic woman”), according to the article.

Polk County, Missouri marriage records indicate that Harrell performed marriages in early 1841, and he received a land grant for 80 acres in Dallas County on April 10, 1843. Apparently, Harrell was bi-vocational – a Baptist minister and a farmer. However, in 1849 Harrell got a case of gold fever. Gold was first discovered in early 1848 and by the end of the year hundreds of people made their way west to seek their fortunes.

Polk County, Missouri marriage records indicate that Harrell performed marriages in early 1841, and he received a land grant for 80 acres in Dallas County on April 10, 1843. Apparently, Harrell was bi-vocational – a Baptist minister and a farmer. However, in 1849 Harrell got a case of gold fever. Gold was first discovered in early 1848 and by the end of the year hundreds of people made their way west to seek their fortunes.

Harrell headed to California sometime after the 1850 census (enumerated on August 10, 1850), leaving Nancy and his children behind. In 1853, Nancy began her journey to California. In 1901, the Guernville Republican told her story:

This undaunted woman who had braved the perils of Missouri frontier life, started westward at the head of an emigration train. Instead of oxen for draft animals, as was the custom, she had 15 cows shod in leather boots for the protection of their feet and drove them in two teams, guiding one team with her own hands. The cows furnished milk enroute and were sold for large sums of money when they reached California. They were worth far more than the gold nuggets which were dug and washed up.

The newspaper article said that the Bray family joined the local First Baptist Church around 1855 or 1856 and the next two censuses indicate that Harrell had returned to farming. The 1860 census recorded that Harrell and Nancy and four of their sons (Harrell, William, Nathaniel and Reuben) were living in Santa Rosa, Sonoma County, California. A young Elisha Bray, 9 years old, was enumerated with them and I assume that perhaps he was their grandson.

In 1870, Nancy and Harrell were enumerated with their son Reuben in Santa Rosa. Two of their grandchildren, Samuel and Joseph Culbertson (daughter Nancy’s children) were present in the same household. Nancy was only 16 years old and married to William Culbertson (age 27) in 1860 and bore at least twelve (possibly thirteen children) of her own.

On February 2, 1877, just two weeks before Nancy’s seventy-sixth birthday, Harrell passed away. According to the Guernville Republican, Nancy had an accident, injuring her hip in 1881 or 1882. At the time the article was written, she had been confined to the County Hospital for nineteen years. “She refused to leave this place, fearing that in death she might be separated from her husband who is buried here”, according to the article.

Nancy was enumerated in the 1880 census with her son Elisha (56), a widower. In 1900, Nancy was counted as a resident (boarder) of the Santa Rosa Poor Farm – her son Elisha was a boarder in the same facility at the age of 77 on June 18, 1900. On July 19, 1900, Elisha passed away and was buried in the same cemetery (Santa Rosa Rural Cemetery) as his father.

Nancy was enumerated in the 1880 census with her son Elisha (56), a widower. In 1900, Nancy was counted as a resident (boarder) of the Santa Rosa Poor Farm – her son Elisha was a boarder in the same facility at the age of 77 on June 18, 1900. On July 19, 1900, Elisha passed away and was buried in the same cemetery (Santa Rosa Rural Cemetery) as his father.

The day of her 101st birthday, February 16, 1902, Reverend Gason and members of the First Baptist Church planned to visit, honoring her with a reception, “most likely the last honor which they will be able to bestow in her lifetime.” At that time, she was reported to have been too weak to leave her cot, but the reception would be held in a corner of the women’s ward. She was in “full possession of her faculties” and eager to greet her guests and celebrate her birthday that day.

A few weeks later, on March 12, 1902, Nancy Crawford Bray passed away and was buried next to her beloved husband. Nancy had 114 descendants – ten children, sixty grandchildren, forty great-grandchildren and four great-great grandchildren. What a life Nancy Crawford Bray must have lived! She outlived her husband and at least two of her children.

I randomly selected Nancy Crawford Bray for a tombstone article several weeks ago, and of course, my rule is that I don’t research known relatives or ancestors for these articles. I unexpectedly found a connection with the Bray family and my Grandmother Okle (Erp) Young’s family.

Harrell Bray was the son of William and Elizabeth Denny Bray. One of William’s brothers, Isiah Bray, married the daughter of my fourth great grandparents Johnathon and Belinda Taylor Brinson, Phoebe Brinson in Kentucky. Phoebe’s sister, Hannah (married to Singleton Earp), is my third great grandmother, so that would make Phoebe my second great grand aunt (if our calculations are correct). Phoebe would be Harrell Bray’s aunt by marriage, and thus Nancy a niece by marriage. The Brinsons lived in Pulaski County, Kentucky as did many other ancestors (Earp, Stogsdill, Sears, Chaney and Simpson).

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Motoring History: The Great Race of 1908 – New York to Paris (via Alaska and Siberia)

The first decade of the twentieth century had already seen its share of automobile races, beginning with the Gordon Bennett Races in France, sponsored by James Gordon Bennett, Jr. who owned the New York Herald newspaper. At the beginning, races were city to city (Paris to Lyon was the first) and after the 1905 the race was known as the French Grand Prix. William Kissam Vanderbilt, Jr. established the first American race event, the Vanderbilt Cup, held on Long Island from 1904 to 1910 and then on to Wisconsin, Santa Monica in 1912 and to San Francisco in 1916.

The races became progressively more daring. In 1907 the Peking to Paris race was held, spanning two continents and over ninety-three hundred miles. That race proved to the world that the automobile craze was not a fluke; however, the next major race would further convince all skeptics of the automobile and its capabilities. Audaciously, after the 1907 race, another race was proposed and this time the race would begin in New York City in the dead of winter and end in Paris, France – via Alaska and Siberia.

The races became progressively more daring. In 1907 the Peking to Paris race was held, spanning two continents and over ninety-three hundred miles. That race proved to the world that the automobile craze was not a fluke; however, the next major race would further convince all skeptics of the automobile and its capabilities. Audaciously, after the 1907 race, another race was proposed and this time the race would begin in New York City in the dead of winter and end in Paris, France – via Alaska and Siberia.

The Great Race of 1908

The Great Race of 1908, sponsored by the New York Times and Le Matin, a Paris newspaper, consisted of six teams (though thirteen had actually entered): one from the United States, one from Italy, one from Germany and three representing France.

This article is no longer available for free at this site. It was re-written and enhanced, complete with footnotes and sources and has been published in the June 2018 issue of Digging History Magazine. Should you prefer to purchase the article only, contact me for more information.

This article is no longer available for free at this site. It was re-written and enhanced, complete with footnotes and sources and has been published in the June 2018 issue of Digging History Magazine. Should you prefer to purchase the article only, contact me for more information.

I invite you to check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Surname Saturday: Doolittle

Doolittle

The surname Doolittle is of Norman origin and gradually Anglicized over time. One of the members of William of Normandy’s expedition was named “Du Litell” or “de Dolieta” (which meant “of Dolieta” a location along the Normandy coast). Rudolph of Dolieta, the Norman nobleman is likely the progenitor of most, if not all, Doolittles in England.

In the fourteenth century, mention is made of Robert Dolittel who received a royal pardon. In the sixteenth century, records mention the names “Dolittle”, “Dolitell”, “Dolitill”, “Dolitle” and “Doolitlie”. In the early seventeenth century the name “Doolittle” begins to appear. Anthony Doolittle, a glover, was married and had three sons and mentioned as an “honest and religious” citizen. His son Thomas was ordained as a Presbyterian minister, and a non-conformist which would be later be referred derisively to as “Puritan”.

In the fourteenth century, mention is made of Robert Dolittel who received a royal pardon. In the sixteenth century, records mention the names “Dolittle”, “Dolitell”, “Dolitill”, “Dolitle” and “Doolitlie”. In the early seventeenth century the name “Doolittle” begins to appear. Anthony Doolittle, a glover, was married and had three sons and mentioned as an “honest and religious” citizen. His son Thomas was ordained as a Presbyterian minister, and a non-conformist which would be later be referred derisively to as “Puritan”.

Some sources suggest that “Doolittle” was an English nickname for a lazy man. However, the man featured in today’s article was undoubtedly not lazy. He appears to be the first Doolittle to immigrate to New England and is considered the progenitor of most of the Doolittle family in America.

Abraham Doolittle

Abraham was born in either 1619 or 1620 and possibly a descendant of Reverend Thomas Doolittle. Abraham married Joane Allen (or “Alling”) and soon afterwards set out for New England. Records indicate Abraham’s presence in Boston in 1640, but he like many others, heard good reports of the fertile lands in what would become Connecticut. Sometime before 1642 the couple arrived in New Haven and built a home. (Note: Although I use the evolved surname of “Doolittle”, Abraham actually used “Dowlittell” as noted in early colonial records.)

Abraham quickly established himself as a well-respected citizen. In 1644, although he was perhaps just twenty-five years old, he was appointed the chief executive officer of the colony. Not only did Abraham deal with issues of concern to his fellow colonists (land, trade, public defense), he also had dealings with the Indians. His participation in New Haven civic affairs was notable as well – according to one historian when an individual of that day was prominent in public affairs it was guaranteed that he was of the highest moral character and an asset to his community.

Abraham quickly established himself as a well-respected citizen. In 1644, although he was perhaps just twenty-five years old, he was appointed the chief executive officer of the colony. Not only did Abraham deal with issues of concern to his fellow colonists (land, trade, public defense), he also had dealings with the Indians. His participation in New Haven civic affairs was notable as well – according to one historian when an individual of that day was prominent in public affairs it was guaranteed that he was of the highest moral character and an asset to his community.

His wife Jane died and in 1663 he married Abigail Moss, the daughter of John Moss. He and John Moss would later participate in the founding of Wallingford, Connecticut. It is believed that Abraham was the first white man to explore the land beyond the Quinnipac River. Wallingford was incorporate as a town on May 12, 1670.

Again, Abraham plunged into the civic affairs of his town, appointed to almost every position available in the town over the next twenty years until his death in 1690 – including treasurer, surveyor of highways and selectman. In 1673 he was appointed sergeant of the “first traine band” and thereafter bore that title. On February 15, 1675 he was appointed to a committee which would found the town’s first Congregational church.

Records indicate that Abraham served his community continuously until just before his death on August 11, 1690. His grave stone is still standing and quite interesting – a stone about four inches thick and perhaps a foot high and wide, which has his initials, age and date of death etched on it.

Theophilus was the youngest son of Abraham and Abigail Doolittle, born on July 26, 1678 in Wallingford. Theophilus was only twelve years old when his father died and when he became of age he received his share of Abraham’s land, becoming a farmer.

On January 5, 1698 he married Thankful Hall, daughter of David and Sarah Rockwell Hall. Theophilus and Thankful named their children: Thankful, Sarah, Henry, David, Theophilus, and Solomon Doolittle. Interestingly, the name Thankful was carried forward as Thankful Doolittle married Timothy Page and they named on of their daughters Thankful, who married Asher Thorpe – and of course, one of their daughters was named Thankful Thorpe.

I believe Thankful is quite possibly a distant relative of mine (note: as with the Tombstone Tuesday articles, I usually just pick a random surname to research). Although I haven’t traced out the entire Hall line, the information so far seems to point to my ancestors as part of the line descended from John and Jane Woollen Hall of England who immigrated and settled in Wallingford, Connecticut. Thankful’s father David was a son of John and Jane Hall.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Feuding’ and Fightin’ Friday: Boyce-Sneed Feud (Because This Is Texas) – Part One

A woman was at the center of this feud in early twentieth-century Texas, a love triangle in which two wealthy cattle ranchers fought over who would win her back – the husband or the lover. The feud might have started, innocently enough, years before when the two men, John Beal Sneed and Albert Boyce, Jr., vied for the attention of Miss Lenora (Lena) Snyder while attending Southwest University in Georgetown, Texas.

John Sneed won her hand in marriage, but after twelve years of marriage Lena wanted a divorce – and with good reason in her estimation as she had been carrying on an affair with none other than her husband’s college rival, Albert Boyce, Jr. Sneed, a cattle buyer and lawyer (Princeton graduate) reacted by committing his wife to a sanitarium in Fort Worth to treat her “moral insanity”. One source related that Lena was treated with calomel (mercury chloride). It had been common practice in the nineteenth and into the first part of the twentieth century to treat people in the advanced stages of syphilis, which typically would be accompanied by mental illness.

John Sneed won her hand in marriage, but after twelve years of marriage Lena wanted a divorce – and with good reason in her estimation as she had been carrying on an affair with none other than her husband’s college rival, Albert Boyce, Jr. Sneed, a cattle buyer and lawyer (Princeton graduate) reacted by committing his wife to a sanitarium in Fort Worth to treat her “moral insanity”. One source related that Lena was treated with calomel (mercury chloride). It had been common practice in the nineteenth and into the first part of the twentieth century to treat people in the advanced stages of syphilis, which typically would be accompanied by mental illness.

This extensive, four-part article is no longer available at the web site. It will, however, be republished in a future issue of Digging History Magazine, complete with footnotes and sources. In the meantime, I invite you to check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

This extensive, four-part article is no longer available at the web site. It will, however, be republished in a future issue of Digging History Magazine, complete with footnotes and sources. In the meantime, I invite you to check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Ghost Town Wednesday: Jollification, Missouri

On September 4, 1848, a forty-acre tract of land in Newton County, Missouri was sold by Frederick Hisaw to John and Thomas D. Isbell for $300. Upon this land the Isbells built a distillery and grist mill (Jolly Mill), perhaps with slave labor, according to local lore. In the 1840 census, Thomas Isbell owned four slaves, but one family history indicated that his slaves were not skilled at carpentry, so slaves belonging to neighbors were used.

On September 4, 1848, a forty-acre tract of land in Newton County, Missouri was sold by Frederick Hisaw to John and Thomas D. Isbell for $300. Upon this land the Isbells built a distillery and grist mill (Jolly Mill), perhaps with slave labor, according to local lore. In the 1840 census, Thomas Isbell owned four slaves, but one family history indicated that his slaves were not skilled at carpentry, so slaves belonging to neighbors were used.

By the 1850 census, John was listed as a “distiller of spirits” and the value of his property was $5,000 (quite an appreciation!). Thomas was nearby living as a farmer with a property value of $1,500. In March of 1852, Thomas and his wife Rebecca sold their portion of the land to John for $2,000, perhaps retaining a small plot for themselves. Thomas died in 1855.

By the 1850 census, John was listed as a “distiller of spirits” and the value of his property was $5,000 (quite an appreciation!). Thomas was nearby living as a farmer with a property value of $1,500. In March of 1852, Thomas and his wife Rebecca sold their portion of the land to John for $2,000, perhaps retaining a small plot for themselves. Thomas died in 1855.

By that time, a small town had sprung up around the mill and the town was named “Jollification”. Listed on the 1850 census were carpenters and masons, so perhaps these individuals helped build the town. On the next census, John’s neighbors were merchants, grocers, clerks, millers and blacksmiths, indicating the town was well-established by 1860 – three general stores, dram shop, blacksmith shop, post office and church. Wagons headed to southern Kansas and the Indian lands beyond came through Jollification, a place to rest and restock supplies – and what frontiersman could resist some “spirits”. John Isbell was said to be one of the wealthiest men in the county.

In addition, John owned eight slaves in 1860. There were over one hundred slave owners in Newton County in 1860, and of course, slavery was a hotly debated topic at that time. The 1820 Missouri Compromise was repealed in 1854 as part of the Kansas-Nebraska Act and the nation was about to explode and split apart.

So as the Civil War neared, John Isbell was said to be quite wealthy – but then something curious and unexplained occurred. No one seems to know just why, but John mortgaged his property (totaling approximately $13,000) and left the area. In 1870, John was enumerated in Newtonia, Newton County, Missouri as a “retired manufacturer” at the age of 52. By 1880 John, at the age of 62, was again a miller. There were quite a few battles fought in Newton County during the Civil War. Newtonia was the site of two significant battles, one in 1862 and the other in 1864. The Second Battle of Newtonia was the last major battle fought west of the Mississippi River.

Some of the village of Jollification was burned, according to some accounts by either “baldknobbers” or “bushwackers” (vigilantes). However, the distillery was spared. Other activity recorded in Jollification during the war consisted primarily of merely “passing through” Jollification, although a few incidences occurred in 1862. On May 7, 1862 a rebel was killed in Jollification, in July a Missouri Cavalry unit (Union) killed 10 guerillas and on October 3, after the first battle of Newtonia, several Union prisoners were held in the Jollification blacksmith shop.

After John Isbell left, the mill and distillery had fallen into disrepair from neglect. After the war ended, George Isbell (perhaps a cousin of John’s) purchased the property for $200 at an auction. George had the property repaired and began to operate the mill and distillery once again. In 1875 George ceased operations of the distillery in protest of Federal taxes on whiskey, but continued to operate the mill until 1894 when he sold it to his nephew George Isbell Brown. The mill site would be referred to in Newton County records as the “Jolly Mill place”. George Brown may have planned improvements on the property but he sold it in 1895 to A.C. Lucas and Son who called it “Jolly Rolling Mills”. Ownership next passed to W.F. Haskins and in 1983 a nonprofit organization was formed to preserve the mill site. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places in October of 1983.

So how did the town gets its name? In the April 20, 1870 edition of the Neosho Times, the story is related how the editor of a rival newspaper learned about the town’s naming. The editor was told that a local man, Able Landers, would visit the distillery every Saturday. After he exchanged corn for whiskey he would gather the men around and call for a “jollification”. After drinking and fighting, the old man invariably using the word “jollification,” the name was applied to the town. However, the editor of the Times strenuously disagreed:

This statement in regard to the place getting its name is most assuredly erroneous, and not only that, but an outrage on old man Landers, who was one of the most high-minded, respectable citizens of the county, and was never known to come to town for the purpose of raising a jollification, which can be substantiated by numerous friends. Two fights only occurred near the distillery, neither of which he was involved in, and it is asserted by his friends that he had nothing to do with naming the place.

Jolly Mill Park is located about an hour southeast of Joplin near Pierce City, Missouri. Some artifacts and historic buildings, including the mill, remain. Looks like a beautiful place to visit!

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Tombstone Tuesday: Lawson Cemetery – Hickman County, Tennessee

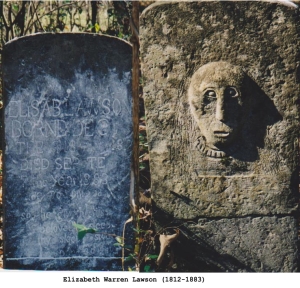

The first thing that intrigued me about this cemetery were two gravestones which are said to have been carved by the decedents’ son. They are unique in that the faces of his parents are carved into the back of each tombstone – the primitive art is striking.

Thomas and Elizabeth Warren Lawson are both buried in the Lawson Cemetery in Hickman County, Tennessee, along with several other Lawsons and Warrens (Elizabeth’s maiden name). Elizabeth died on September 7, 1883 and Thomas died shortly thereafter on December 21, 1883. According to various sources, their oldest son, Shadrach Warren, carved their headstones. The hand prints on the back of Thomas’ stone are said to be the hand prints of his grandchildren, Shadrach’s children, Callie Leona, Etta Lou and Lillie Eveline. The stones were carved from grindstone taken from Grindstone Hollow near Hassell’s Creek.

This article was incorporated in a feature article, entitled “Are You One of Those Kind of People?”, published in the October 2018 issue of Digging History Magazine. Should you wish to only purchase the article, contact me.

This article was incorporated in a feature article, entitled “Are You One of Those Kind of People?”, published in the October 2018 issue of Digging History Magazine. Should you wish to only purchase the article, contact me.

I invite you to check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!