Surname Saturday: Trowbridge

The Trowbridge surname was seen as early 1184 in Wiltshire County, England as “Trobigge”, probably derived from the Old English word which translated means someone dwelling near a wooden bridge.

Later recorded instances of the name include: Troubrug (1212); William de Trewebrugg (1275); Edward Trobridge of Yorkshire listed in 1379 on the Yorkshire Poll Tax; George Trobrydge enrolled at Oxford in 1583. Spelling variations also include: Troubridge, Trobridge, Trubbrudge, Trubbridge, Trawbridge and others, perhaps such as Strawbridge or Strowbridge.

Following are stories of the earliest Trowbridge to immigrate (sort of) to America and his youngest son.

Thomas Trowbridge

The first settler in America to bear the surname was Thomas Trowbridge, a mercer (dealer in fine fabrics) who immigrated from the town of Taunton in Somersetshire, England possibly as early as 1634 or 1636. He and his wife Elizabeth appear in 1636 records as Mr. And Mrs. and she was listed in 1638 church records. Their youngest son James was baptized in the Dorchester, Massachusetts church in 1637 or 1638.

He and his family moved to the New Haven colony in 1638, but Elizabeth only lived another year or two afterwards. Records seem to indicate that Thomas spent a lot of time traveling back and forth to England, throughout the colonies and to the West Indies, presumably in pursuit of business interests. Sometime after Elizabeth’s death an incident occurred when he left his three young sons in the care of his steward Henry Gibbons.

He and his family moved to the New Haven colony in 1638, but Elizabeth only lived another year or two afterwards. Records seem to indicate that Thomas spent a lot of time traveling back and forth to England, throughout the colonies and to the West Indies, presumably in pursuit of business interests. Sometime after Elizabeth’s death an incident occurred when he left his three young sons in the care of his steward Henry Gibbons.

Gibbons turned out to be an untrustworthy caretaker of Thomas’ estate. The citizens of New Haven were alarmed at his malfeasance, and in November of 1641 a court ordered an attachment be placed on Thomas’ property to pay off all indebtedness. The court also placed the children in the care of Thomas Jeffrey and his wife until “their father shall come over or send to take order concerning them”. In the meantime the Jeffreys were to make sure the children were well educated “and nurtured in the fear of God.”

Whether Thomas ever returned to the colonies is unclear – if he did it was only perhaps for brief visits. The only records thereafter seemed to be related to Gibbons’ mishandling of Thomas’ affairs. After Thomas’ father died he was the sole surviving son and likely took a prominent role in Taunton. Records indicate that he often wrote to authorities in New Haven (amazingly, Gibbons continued to handle his affairs, at least until his sons came of age).

It does seem strange that Thomas would be so detached from his sons’ upbringing, but it appears he must have been content with the court-ordered arrangement. His children received an excellent education under the tutelage of Ezekiel Cheever, who in 1643 or 1644 requested funds out of Thomas Trowbridge’s estate to cover the cost of his services.

After his son William came of age, he tried to ascertain the value of his father’s estate that remained in New Haven. His father, unable to obtain an accurate account from Gibbons, finally gave his sons power of attorney as the proprietors of his estate. Their later attempts to recover losses from Gibbons were not settled until after Thomas’ death on February 7, 1672.

Deacon James Trowbridge

Thomas’ youngest son James inherited land in Dorchester, and after reaching adulthood and having married, settled there. He married Margaret Atherton on December 30, 1659. To their marriage were born seven children: Elizabeth (1660), Mindwell (1662), John (1664), Margaret (1666), Thankful (1668), Mary (1670) and Hannah (1672).

The family moved to what is now Newton, Massachusetts in 1664 and James was made a freedman in May of 1665. Margaret died in 1672 and on January 30, 1674 he married Margaret Jackson, daughter of Deacon John and Margaret Jackson. He and Margaret had seven children together: Experience (1675); Thomas (1677); Deliverance (1679); James (1682); William (1684); Abigail (1687) and Caleb (1692).

James remained in Newton the rest of his life and was one of the first members of the Newton Congregational Church. When his father-in-law Deacon John Jackson passed away, he was chosen to succeed him and served in that office until his death.

James also served in King Philip’s War after being appointed as a lieutenant, resigning on October 10, 1677. He was involved in civic affairs in his community, serving on the grand jury of Massachusetts, as clerk of writs and in the general court in the early 1700’s. By the time he died on May 22, 1717, little remained of his estate because he had distributed gifts to his children throughout his lifetime.

Other Trowbridge families later immigrated to America. In case you missed yesterday’s Feisty Female article about Grandma Gatewood, check it out here. One of her ancestors, Levi Trowbridge, of a different line than Thomas Trowbridge, served as one of the Green Mountain Boys under the command of General Ethan Allen during the Revolutionary War.

Sources:

The Trowbridge Genealogy: History of the Trowbridge family in America (1908) by Francis Bacon Trowbridge

The Trowbridge family, or, Descendants of Thomas Trowbridge, One of the First Settlers of New Haven, Connecticut (1872) by Reverend F.W. Chapman

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Feisty Females: Grandma Gatewood (Part I)

After becoming the first woman to hike the Appalachian Trail solo at the age of sixty-seven in 1955, today’s “Feisty Female” remarked to Sports Illustrated upon completing the trek, “I would never have started this trip if I had known how tough it was, but I couldn’t and wouldn’t quit.” Such was the grit and determination of Emma Gatewood, a.k.a. Grandma Gatewood – how that spirit became embodied in her is the subject of today’s article, with her story concluding next Friday.

After becoming the first woman to hike the Appalachian Trail solo at the age of sixty-seven in 1955, today’s “Feisty Female” remarked to Sports Illustrated upon completing the trek, “I would never have started this trip if I had known how tough it was, but I couldn’t and wouldn’t quit.” Such was the grit and determination of Emma Gatewood, a.k.a. Grandma Gatewood – how that spirit became embodied in her is the subject of today’s article, with her story concluding next Friday.

Emma Rowena Caldwell was born on October 25, 1887 in the Guyan Township of Gallia County, Ohio to parents Hugh Wilson and Esther Evaline (Trowbridge) Caldwell, she being one of fifteen children (ten girls and five boys).

This article was featured in the May 2018 issue of Digging History Magazine. Emma Gatewood — what an amazing woman! The May issue also featured articles on the Civil War aftermath, including “Coughing up Relics”, “About Those Pensions” and “Left-Handed Penmanship”.

This article was featured in the May 2018 issue of Digging History Magazine. Emma Gatewood — what an amazing woman! The May issue also featured articles on the Civil War aftermath, including “Coughing up Relics”, “About Those Pensions” and “Left-Handed Penmanship”.

I invite you to check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Wild Weather Wednesday: The Great Galveston Hurricane of 1900

On September 8, 1900 a massive storm was raging and headed for the Texas coast. The storm, which may have originated off the western coast of Africa, had already inflicted heavy damage in New Orleans and was heading west.

On September 8, 1900 a massive storm was raging and headed for the Texas coast. The storm, which may have originated off the western coast of Africa, had already inflicted heavy damage in New Orleans and was heading west.

The city of Galveston, located on thirty mile-long Galveston Island, was incorporated as a city in 1839 and by 1900 had become a major United States port (third busiest), and approximately forty thousand residents called it home. The island’s highest point was a mere 8.7 feet above sea level, with most of it averaging about half that altitude. The city was fast becoming a metropolis on par with other U.S. cities like New Orleans and San Francisco. The New York Herald went so far as to call it the “New York of the Gulf”. Galveston had electricity, telephone and telegraph services, several hotels, expensive restaurants and more.

The city of Galveston, located on thirty mile-long Galveston Island, was incorporated as a city in 1839 and by 1900 had become a major United States port (third busiest), and approximately forty thousand residents called it home. The island’s highest point was a mere 8.7 feet above sea level, with most of it averaging about half that altitude. The city was fast becoming a metropolis on par with other U.S. cities like New Orleans and San Francisco. The New York Herald went so far as to call it the “New York of the Gulf”. Galveston had electricity, telephone and telegraph services, several hotels, expensive restaurants and more.

This article is no longer available for free at this site. It was re-written and enhanced, complete with footnotes and sources and has been published in the March 2018 issue of Digging History Magazine. Should you prefer to purchase the article only, contact me for more information.

This article is no longer available for free at this site. It was re-written and enhanced, complete with footnotes and sources and has been published in the March 2018 issue of Digging History Magazine. Should you prefer to purchase the article only, contact me for more information.

I invite you to check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? That’s easy if you have a minute or two. Here are the options (choose one):

- Scroll up to the upper right-hand corner of this page, provide your email to subscribe to the blog and a free issue will soon be on its way to your inbox.

- A free article index of issues is available in the magazine store, providing a brief synopsis of every article published in 2018. Note: You will have to create an account to obtain the free index (don’t worry — it’s easy!).

- Contact me directly and request either a free issue and/or the free article index. Happy to provide!

Thanks for stopping by!

Tombstone Tuesday: General Washington Gentry of Johnson County, Tennessee

I gotta say this was a difficult article to research – so darn many General Washington Gentry’s or George Washington Gentry’s or General George Washington Gentry’s in Johnson County, Tennessee it seemed. I think (I hope) I have figured it out though. There are some interesting family stories and some very unique names given to his children. This family was also related by marriage to the “Ocean Sisters” I wrote about last week. In case you missed it, you can read it here.

I gotta say this was a difficult article to research – so darn many General Washington Gentry’s or George Washington Gentry’s or General George Washington Gentry’s in Johnson County, Tennessee it seemed. I think (I hope) I have figured it out though. There are some interesting family stories and some very unique names given to his children. This family was also related by marriage to the “Ocean Sisters” I wrote about last week. In case you missed it, you can read it here.

Today’s subject was born General Washington Gentry on September 14, 1810 to parents Benjamin and Rhoda (Wilson) Gentry. According to Gentry family research, there don’t seem to be any other children named General Washington in Benjamin’s generation, but there were perhaps nephews who were given the same or similar name in later generations, that is if census and military records are correct. Interestingly (at least to me) is that one of Benjamin Gentry’s brothers, William, ended up in Pulaski County, Kentucky which is where many of my ancestors lived.

There are two marriage records for General W. Gentry. His first wife, Minerva Blevins, apparently died not long after their marriage on August 25, 1841. His second marriage to Eliza Ann “Lizzie” Rambow (Rambo) occurred on March 24, 1842. Their first child, Mahlon, was probably born in 1843, according to census records, although at Find-a-Grave it says that his date of birth was February 14, 1841 – I think not. Their other children, with approximate birth dates, were, according to census records:

Cornelia (1845)

Andrew Nameyard (or Namyard) (1848)

Bartholomew (1850)

Carnassie Carrie “Sis” (1853)

Parnassie (1854)

Ferdinand (1858)

General Rosencrance (1860)

What is the meaning of the name “Nameyard” or “Namyard”? For the Burmese, “namyard” is a word for “libation water.” More than one web site points out that it is “Drayman” spelled backwards – yes, that’s true, but that would be really odd to give your child a backwards-spelled name. One reference was found in an archive of the Lubbock Avalanche-Journal: “For mod pulverized namyard manure delivered” – but perhaps this was actually supposed to be “farmyard manure” (I’m just throwing that out there). When a credible reference to the word is found on the internet, it seems to be associated with Asian cultures. Not sure about that one but plenty curious about its meaning — if anyone reading this article has an answer, please share!

For census records there is listed a “Bartholomew” in 1860 but his 1870 marriage record has it spelled “Bartholamu”. Carnassie and Parnassie sound like twin names but they were born two years apart. To further complicate research, Parnassie married a cousin named General Leach Gentry, son of General George Washington (or possibly just George Washington, since only his initials were used on his gravestone) Gentry who was born in 1830. Parnassie may have died during the 1918 influenza pandemic, according to her death certificate.

For census records there is listed a “Bartholomew” in 1860 but his 1870 marriage record has it spelled “Bartholamu”. Carnassie and Parnassie sound like twin names but they were born two years apart. To further complicate research, Parnassie married a cousin named General Leach Gentry, son of General George Washington (or possibly just George Washington, since only his initials were used on his gravestone) Gentry who was born in 1830. Parnassie may have died during the 1918 influenza pandemic, according to her death certificate.

There don’t seem to be any ancestors or family members named “Rosencrance” or “Ferdinand”. Family historians believe that Rosencrance was named after a Northern general, possibly William Rosencrans, who served under Grant at one time. All in all, however, these names seem rather unusual, perhaps a bit exotic, for a Tennessee family to give to their children.

A Tennessean naming one’s child after a Union general also seems a bit odd, dangerous or offensive given the time when he was born, but another family legend says that General was hung by Rebel Home Guards because he refused to choose between the North or South. This is certainly possible because there aren’t any more records of General after the 1860 census, when his ninety-two year old widowed mother Rhoda was also residing with him. In 1870, Eliza was widowed and five of her children were still living with her.

The rest of the family legend goes like this: The Home Guards burned General’s house down and Eliza got thirteen children out and the family Bible off the fireplace mantle. Rosencrance, said to have been named after a famous Northern general was hidden in the hills with various relatives. Another part of the story has General’s nephew John Roe Gentry (Pacific’s husband – see last week’s article on the “Ocean Sisters” linked above) saying that his aunt, presumably Eliza, hid two boys under General’s bed when the Rebels came looking for men and boys to conscript – perhaps one was Rosencrance and the other Ferdinand?

This may very well be just a “legend” – for one thing there is no record indicating General and Eliza had thirteen children. There is a gravestone which appears to belong to General, although the name is “W.G. Gentry”. It states that he died on September 14, 1864, his fifty-fourth birthday. Eliza, about thirteen years younger than General, according to her gravestone, died in 1902. However, the 1870 census records her age as fifty-nine, which would mean she had been been born in approximately 1811.

A research note – Ferdinand Gentry is actually how I discovered the Gentry’s of Johnson County (and the Ocean Sisters). After my recent visit to Estacado Cemetery, I was researching a grave belonging to Margaret D. Gentry. On her tombstone she was referred to as the wife of Ferdinand Gentry. I doubt General’s Ferdinand was her husband because of the age difference, but I just never know what a search will lead to – in this case two interesting Tombstone Tuesday about related families in Johnson County, Tennessee.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Surname Saturday: Kitten

Those who regularly read the Surname Saturday articles know that there are usually multiple theories as to a surname’s origin. Such is the case again today with the Kitten surname.

Those who regularly read the Surname Saturday articles know that there are usually multiple theories as to a surname’s origin. Such is the case again today with the Kitten surname.

According to House of Names, the Kitten surname is of Anglo-Saxon origin, possibly residents of a village in Durham or Rutland called Ketton. Alternatively, there was also a place called Keaton in County Devon. Therefore, this source proposes that Kitten is a habitational name. Spelling variations include: Keaton, Keeton, Ketton, Keton, Ketyn and Keetyn and more.

One early American immigrant to Maryland, Theophilus Kitten, is said to have changed his name to Caton. According to the Patronymica Britannica:

CATON. Until the close of the XVI. cent., Catton and De Catton; from the manor of Catton near Norwich, which in Domesday is spelt Catun and Catuna. The family were located in Norfolk from time immemorial till the middle of the last century. The latinizations Catonus, Gathonus, and Chattodunus occur in old records.

In 1736, Stephen Kitten (parents Edward and Mary) was baptized in the St. Faiths District of Norfolk and his sister Ruth was baptized in 1742. According to 1891 England and Wales census data, Norfolk had the highest concentration of families with the Kitten surname (29% or 4 of 14).

Another theory (Ancestry.com) suggests Kitten is a “reduced form of Irish or Scottish McKitten, of uncertain etymology; perhaps a variant of Mac Curtáin (or McCurtain)”. New York passenger lists verify that a significant number of Kitten immigrants came from Ireland, followed by England, Germany, Prussia, Denmark and Bavaria – which leads to the third theory.

Again, Ancestry.com theorizes that the surname may also be a variant of the German name “Gitten” or “an altered spelling of German Kütten”. Some family historians believe that the name possibly derives from various locations in Germany:

Possibly the name of a farm near Ibbenbueren in the Steinfurt district (North Rhine-Westphalia) region.

The Kittendorf Castle was built in 1853, approximately one hundred kilometers north of Berlin.

In the Bavarian district of Oberallgäu, there is a village by the name of Kutten.

In Saxony, another village by the name of Kütten.

With the last theory in mind, following is the story of German-born Florenz Kitten, whose family fled the political upheaval in Prussia and settled in Ferdinand, Indiana after arriving in America in either the late 1840’s or 1850.

Florenz Kitten

Gerhard Florenz Kitten, the son of Henrich and Theresia (Heeke) Kitten, was baptized on September 4, 1840 in Katholisch, Ibbenbueren, Westfalen, Prussia. This is according to records of German baptisms which occurred between 1558 and 1898. Curiously, however, most family researchers record October 25, 1840 as his birth date with sources coming from other ancestry family trees. If he indeed was baptized on September 4, perhaps he was born on August 25 rather than October 25(?).

The political upheaval in Prussia began the same year of his birth when King Frederick William III died. His oldest son, Frederick William IV, ruled from 1840 until 1861, a reign that was marked by disastrous economic conditions and political revolution. According to the Encyclopedia of 1848 Revolutions:

Most German historians of the nineteenth and early twentieth century negatively characterized Frederick William IV as gifted but mercurial and contradictory, an artist and aesthete rather than a hard-headed politician, a “Romantic on the throne” who was out of step with his times. . . .The young crown prince was less martially inclined than his younger brother and eventual successor, Prince William. Rather, he possessed a fertile artistic imagination, strong religious feelings, a passion (and a real talent) for architecture, an attachment to Romantic literature (especially the medieval fantasies of Fouqué), and an overabundant emotionalism. . . . After his father’s death in June 1840, Frederick William responded to pressures for change in Prussian society by embarking upon a series of experiments (the United Committees of 1842, the Evangelical General Synod of 1846, and the United Diet of 1847), to transform state and church on the basis of his organic-corporative ideals.

With the instability came uprisings and the inevitable bloodshed, all this eventually compelling the Kitten family to leave their homeland and immigrate to the United States for the hope of a better (and more peaceful) life. Heinrich (Henry) was a wooden shoemaker whose craft, in the mid-1800’s, would have been most needed in a German-populated area. That place turned out to be Dubois County, Indiana in the town of Ferdinand.

Ferdinand had been established on January 8, 1840 by Father Joseph Kundek who had served as a missionary to about forty German Catholic families settling the area in 1839. He acquired the land and planned the town’s grid. Not only would the town be a place for German Catholics to settle when they arrived in America, but lot sales would also fund the construction of the church.

To compel more German settlers to come to Dubois County, advertisements were placed in neighboring states’ newspapers. The town’s name was originally Ferdinandsstadt (a very German name) in honor of Ferdinand, the emperor of Austria at the time. Eventually the name was simplified and shortened to Ferdinand.

The German settlers were hard-working, honest folks. The Illustrated Historical Atlas of the State of Indiana (1876) stated that “Ferdinanders are a happy and industrious people.” It would be a perfect fit for the Kitten family.

Florenz was mostly likely around the age of ten when they arrived in Ferdinand. There he attended school, and like most children of the day, worked on the family farm. He was also a “tinkerer”. The Industrial Revolution had brought changes to manufacturing, farming, transportation and more, but “tinkering” wasn’t a recognized trade so Florenz worked on the family farm until the age of nineteen, when he began to work as a carpenter.

On June 29, 1869 he married Maria Katherina Luegers. Following their marriage, Florenz purchased a lot and built a house in Ferdinand. The second floor of their home was his workshop, where he began tinkering again, this time with steam. After a few years, he began to build steam engines and threshers around 1880. For the 1880 census he was enumerated as a manufacturer of threshing machines. He and Katherina (Catherina) had one son, Joseph, aged nine.

After his inventions found a solid market, Florenz built a two-story factory next to his home – The Kitten Machine Shop. He applied for and received a patent improvement for his threshing machine straw carrier, and in 1889 was granted a patent (#409,594) for his improved steam engine design. In 1882 Florenz had begun building traction engines. These engines no longer required “horse” power, representing one of the greatest improvements to date for engine machinery. The engine, however, weighed over seventeen thousand pounds and most were sold within a short radius of Ferdinand. His traction engines were unique and stood out with yellow and red paint.

After his inventions found a solid market, Florenz built a two-story factory next to his home – The Kitten Machine Shop. He applied for and received a patent improvement for his threshing machine straw carrier, and in 1889 was granted a patent (#409,594) for his improved steam engine design. In 1882 Florenz had begun building traction engines. These engines no longer required “horse” power, representing one of the greatest improvements to date for engine machinery. The engine, however, weighed over seventeen thousand pounds and most were sold within a short radius of Ferdinand. His traction engines were unique and stood out with yellow and red paint.

In 1900, Joseph, unmarried, was working as a foreman at the foundry alongside his father. Six years later Florenz stepped aside and handed the business over to Joseph. In 1908 Joseph sold the business to John Hassfurther and John P. Reinecker and the name was changed to Ferdinand Foundry and Machine Works.

By 1910, Joseph was married with a young family of three children, enumerated at the same residence as his parents. He took the business back in 1914 and he and his wife Elizabeth had three more children before his death in 1918. Just over two months after the 1920 census, Florenz died on March 22 at the age of seventy-nine.

Following Joseph’s untimely death, Elizabeth and her father managed the company until Elizabeth and Joseph W. Bickwermert bought the company. Bickwermert became the sole owner in 1935 and changed the name to Ferdinand Machine Company. The company changed hands again in 1945 and by the 1950’s had entered a new market: woodwork finishing.

A man by the name of Deere had designed a tractor and gradually the steam engine had gone the way of the dinosaur. To remain viable, the machine company added new products and in 1952 was incorporated as DuBois County Machine Company, Inc. Over the years the company changed hands several times and moved some of its operations elsewhere, although the Ferdinand shop remained open. In 1997 the machine company employed seven engineers.

Today the company, Dubois Equipment Company, Inc. is headquartered in Jasper, Indiana and proclaims itself a leader in the “wood finishing industry for over 50 years and has been the primary producer of complete flat line finishing systems for prefinished wood flooring for the past 25 years.” It’s unfortunate, however, to note the company’s history doesn’t include a mention of the man who founded the original machine shop in 1868.

A great resource for all things Kitten can be found at Amazon (The Whole Kitten Caboodle). I utilized this book and other resources recently to create a custom-designed family history chart for a Kitten family member. Want a chart of your own? Contact me: [email protected] for more information on pricing and ongoing special promotions. More chart samples here: https://digging-history.com/charts/

Note: All pictures are from the Ferdinand Historical Society collection.

Other article sources: Farm Collector (here and here), Ferdinand Historical Society.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Feudin’ and Fightin’ Friday: Colorados y Azules (Some Things Never Change)

As the political rule-of-thumb goes, most people don’t pay attention to upcoming national elections until after Labor Day. Here’s a look back at an era gone by – or is it? As another saying goes, “some things never change”.

As the political rule-of-thumb goes, most people don’t pay attention to upcoming national elections until after Labor Day. Here’s a look back at an era gone by – or is it? As another saying goes, “some things never change”.

Today we are accustomed to the color-coded political classification system of “red states” vs. “blue states”. The concept, however, is not a new one. Following the Civil War, political parties in South Texas used a system to help illiterate or Spanish-speaking voters utilize ballots which were printed in English. This practice started in the 1870s and continued until the 1920s.

The system revolved around what was called “boss rule”. In that era, elections were a big deal (they still should be, but that’s another story) with each side attempting to outdo the other with parades, bands and dances. Democrats Stephen Powers and James G. Browne organized the Democrats of Cameron County into a Blue Club, with about one hundred members, both Anglo and Hispanic.

The system revolved around what was called “boss rule”. In that era, elections were a big deal (they still should be, but that’s another story) with each side attempting to outdo the other with parades, bands and dances. Democrats Stephen Powers and James G. Browne organized the Democrats of Cameron County into a Blue Club, with about one hundred members, both Anglo and Hispanic.

The Republicans of Cameron County founded their own organization, the Red Club. Surrounding counties soon organized their own Red and Blue (“Colorado y Azule”) Clubs. Again, here is where not much has changed, for the Blues’ success depended on the votes of Mexican Americans, Mexicans living in Texas AND Mexicans living on the other side of the border.

Essentially, the Mexican vote was “bought” since the dances were held with all kinds of merriment and libation, where the attendees were “taught” how to vote. In 1902 a new direct primary system was developed, so after being taught how to vote the Mexicans would receive poll-tax receipts. It was also common for voters to receive transportation to and from the polls, especially those who lived in remote areas.

A Mexican alien need only declare his intent to become a citizen (whether he actually did or not I would imagine) to be allowed to vote in elections held in those counties along the border. Hundreds of Mexicans would be brought to the county clerk offices of those border counties, declare their intent to become U.S. citizens and then were shuffled off and allowed to vote.

To further assist these aliens in voting “correctly” the ballots were color-coded: red for Republican and blue for Democrat (although in some counties the coding was reversed). Party officials and interpreters were on hand to make sure the aliens voted according to the officials’ preference. Of course, this made the whole voting process a total sham with the ballot boxes controlled by party or “boss rule”. However, that didn’t stop the practice from continuing until 1927.

Typically, on the day before an election was held, potential voters assembled in town and were fed plenty of food and liquor – and maybe a little cash too. In Starr County, the Blues were Republicans and the Reds were Democrats. The Reds had been in power since 1868 and in 1898 the Blues were challenging. W.W. Shely, a former Texas Ranger and sheriff of the county since 1884, was the leader of the Reds. Shely had already deputized about one hundred officers to guard the polling places and work for the Democratic ticket.

Complaints were filed alleging that mescal, an illegal alcoholic beverage, had been smuggled in from Mexico, presumably to ply voters with liquor the day before the election. John Spalt, a Customs Inspector, met up with two suspected smugglers and attempted to search them until a Democrat candidate for county clerk, Fred Marks, showed up to intervene. Marks fatally wounded Spalt in the back and was jailed. A few days later one of the special Blue deputies shot and killed Joe Magena, a Red, in retaliation.

During the 1906 elections, Starr County was the scene of more political violence, followed by another incident in early 1907:

On January 27, 1907, Gregorio Duffy, the unsuccessful candidate for sheriff, was gunned down in a saloon by the elected sheriff and his two deputies. This killing, the most notorious murder in the history of Rio Grande City, was far more than just a barroom fight, but a fitting culmination for an extremely violent county election that had impact far beyond its boundaries. This election that began with the murder of Judge Stanley Welch on its eve and saw the killing of four unidentified Mexicans by the Texas Rangers before the count of the ballots was complete, defined South Texas for generations. The Starr County Election of 1906 marks the violent and painful transition to Boss Rule. (Origins of Boss Rule in Starr County, by Hernán Contreras, p. 3)

Texas border counties operated a highly-charged political environment, especially during the post-Civil War era. The Jaybird-Woodpecker War was another example of explosive Texas politics. Today, political parties battle back and forth in the mass media, social media and Twitter. In days gone by, the two parties often settled their differences at the point of a gun – today we can be thankful that some things DO change.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

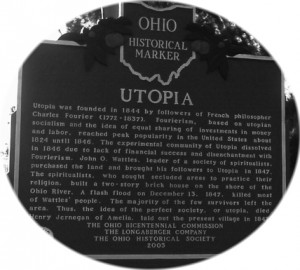

Ghost Town Wednesday: Utopia, Ohio

The period of history encompassing the early to mid-1800’s was marked by the emergence of several utopian societies in America, presumably founded to establish their own version of “heaven on earth”. Sir Thomas Moore had first coined the Greek term for his 1516 book entitled Utopia. Utopia was a fictional island society located in the Atlantic Ocean. The term is often used to describe an intentional community that is established to engender an ideal society.

The period of history encompassing the early to mid-1800’s was marked by the emergence of several utopian societies in America, presumably founded to establish their own version of “heaven on earth”. Sir Thomas Moore had first coined the Greek term for his 1516 book entitled Utopia. Utopia was a fictional island society located in the Atlantic Ocean. The term is often used to describe an intentional community that is established to engender an ideal society.

Several of the Utopian religious societies which sprung up in the nineteenth century were off-shoots of the Second Great Awakening. Some had roots in the eighteenth century, both in America and Europe. The social experiment which sprung up in Ohio in 1844 had its roots in Europe as followers of French philosopher Charles Fourier.

Several of the Utopian religious societies which sprung up in the nineteenth century were off-shoots of the Second Great Awakening. Some had roots in the eighteenth century, both in America and Europe. The social experiment which sprung up in Ohio in 1844 had its roots in Europe as followers of French philosopher Charles Fourier.

Essentially, Fourier’s ideas were the forerunner to communism since he believed that the perfect society was one where everyone shared work and profits, all living together in self-contained and structured communities. He also designed the sprawling building commune residents would dwell in, calling it a phalanstère from the Greek word “phalanx”. The center portion of the complex would be for shared activities such as meetings, dining, libraries and so on.

One area off the center was for “noisier” work activities such as carpentry and the other for living quarters and social halls. The premise of the society was that very soon the world was about to enter a 35,000 year-long period of peace. Not surprisingly, two years after its founding the experiment failed because it wasn’t profitable, even after extracting fees from would-be residents of Utopia.

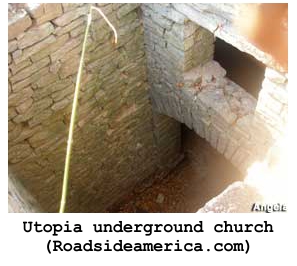

However, that didn’t stop another fellow by the name of John O. Wattles from attempting the exact same thing. Wattles, as it turns out, made a critical mistake when he purchased the land and brought his own followers to Utopia in 1847. He decided to move the community closer to the Ohio River. The structures, including an underground church where secret rituals were practiced, were completed in early December of that year — and the timing could not have been worse.

On December 13, 1847 one of the worst floods of the nineteenth century occurred along the Ohio River. Unfortunately, most of Wattle’s followers were killed when a flash flood collapsed the walls of one of the social halls where a dance was being held that night. The few that survived later left the area. Like Moonville, Ohio (see a past article here), the area is said to be haunted, especially on rainy nights (dripping ghosts and all kinds of spooky noises – ooooh!).

On December 13, 1847 one of the worst floods of the nineteenth century occurred along the Ohio River. Unfortunately, most of Wattle’s followers were killed when a flash flood collapsed the walls of one of the social halls where a dance was being held that night. The few that survived later left the area. Like Moonville, Ohio (see a past article here), the area is said to be haunted, especially on rainy nights (dripping ghosts and all kinds of spooky noises – ooooh!).

The next experimental society was organized by Josiah Warren, sometimes referred to as America’s first anarchist. His views clearly leaned in that direction: “statute laws are at best hindrances, and must be swept away, not by violence, but by the slowly evolved sense of justice and equity which eventually undermine all surviving forms of authority.”

Warren had been involved in the New Harmony community in Indiana, but after leaving there set out to establish his own experimental community. He had his own followers, but for his new community to grow, new settlers would be required to receive an invitation to join the original settlers. There were noted differences in the structure of Warren’s community; rather than shared property, land was owned individually but goods and services were traded by exchanging labor amongst residents rather than cash transactions, a sort of barter system.

The community did experience growth, but the invitation requirement for new settlers proved difficult to implement and maintain. Land prices were also rising and then the Civil War began. Also, Warren had departed Utopia the year after he founded it, returning occasionally to visit. By 1875 some of the original settlers remained, although the area was known then as Smith’s Landing.

In 2003, Ohio erected an historical marker for “Utopia”. As Roadsideamerica.com points out, the town of Utopia is not entirely abandoned today:

Utopia has a tiny general store, but the old couple inside, chain-smoking, couldn’t offer us any postcards or souvenirs. “Is it utopian here?” we asked. They hacked and laughed.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Tombstone Tuesday: The “Ocean Sisters” of Johnson County, Tennessee

Andrew Garfield Shoun and Elizabeth Powell married in 1817 and began raising a family in 1818 with the birth of their first child Andrew. Then came George Hamilton (1822), Rachel Catherine (1823), Isaac Harvey (1825) and Joseph Nelson (1827). In 1829 their first “Ocean” daughter, Elizabeth Atlantic Ocean, was born, followed by Mary and another “Ocean” daughter, Barbary Pacific Ocean, in 1834. They rounded out their family with Elva Olivene (1836) and Frances Eve (1838).

Andrew Garfield Shoun and Elizabeth Powell married in 1817 and began raising a family in 1818 with the birth of their first child Andrew. Then came George Hamilton (1822), Rachel Catherine (1823), Isaac Harvey (1825) and Joseph Nelson (1827). In 1829 their first “Ocean” daughter, Elizabeth Atlantic Ocean, was born, followed by Mary and another “Ocean” daughter, Barbary Pacific Ocean, in 1834. They rounded out their family with Elva Olivene (1836) and Frances Eve (1838).

Most of their children had somewhat “normal” names like Andrew, George and Mary, but for some reason they blessed two of their daughters with middle names of the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. Elizabeth was obviously named after her mother. Barbary, according to will records, appears to have been a family name (her grandmother was named either Barbara or Barbary).

Most of their children had somewhat “normal” names like Andrew, George and Mary, but for some reason they blessed two of their daughters with middle names of the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. Elizabeth was obviously named after her mother. Barbary, according to will records, appears to have been a family name (her grandmother was named either Barbara or Barbary).

This article has been removed from the free side of the site. It has been significantly updated with new research and featured in the March-April 2019 issue of Digging History Magazine. Purchase the issue here or contact me to purchase a copy of the article only.

Surname Saturday: Golightly

Most sources agree that today’s surname is of English or Scottish origin, although uncertain as to whether the name is merely habitational or perhaps derived from Old and Middle English. It’s possible that the Scottish version was habitational, named after a village, town or other locale – perhaps a place which no longer exists.

The English version is thought to have derived from a combination of the pre-seventh century Old English word “gan” and the Middle English word “lihtly” or possibly both of Middle English – “gon” for “to go” and “lihtly”. The second part of the word, “lihtly”, could also have originally derived from the Old English word “leohylic”. Either way, the word would have most likely designated someone light of foot like a messenger.

Spelling variations include: Galletly, Gallightly, Gellatly, Gillatly, and more. William Galithli appeared at the beginning of the 13th century. The earliest recorded spelling of the name might have been Rannulf Golicthli in 1196 duirng the reign of Richard I (“The Lionheart”).

At the end of the 13th century, Henry Gellatly appeared as the illegitimate son of William the Lion. According to 4Crests.com, “in Ireland the name is the Anglicized form of the Gaelic Mac on Ghalloglaigh ‘the son of the gallowglass’. Other instances of the name include Henry Golitheby, Ranald Galychtly and John Galichly.

At the end of the 13th century, Henry Gellatly appeared as the illegitimate son of William the Lion. According to 4Crests.com, “in Ireland the name is the Anglicized form of the Gaelic Mac on Ghalloglaigh ‘the son of the gallowglass’. Other instances of the name include Henry Golitheby, Ranald Galychtly and John Galichly.

Ancestry.com lists but a few patriots with the Golightly surname during the Revolutionary War. The appearance of the name in America picks up, however, in the nineteenth century, with several serving in the Civil War, and predominantly for the Confederacy. Texas appears to have been home to more individuals bearing this surname than other states by the early 20th century, with perhaps the exception of South Carolina.

One of the earliest Golightly immigrants to South Carolina had an unusual forename: Culcheth Golightly. He arrived in that colony at least by 1733 according to family historians.

Culcheth Golightly

Culcheth Golightly was born to parents Robert and Dorothy Fenwick Golightly and christened on November 7, 1706 at Newcastle Upon Tyne in County Northumberland, England. His first name was the surname of his Fenwick grandmother, Ann Culcheth Fenwick. The family was an old and prominent family of County Northumberland and some believe that one of Culcheth’s ancestors, John Golightly, may have immigrated to Virginia in 1688 having previously lived in either Northumberland or Durham County, England.

South Carolina marriage records indicate that Culcheth Golightly married a widow, Mary Elliott (neè Butler), on April 7, 1746. Records also indicate that he was enumerated in the 1740 and 1741 South Carolina censuses in St. Bartholomew Parish. Whether or not he had been married prior to 1746 is unclear. He owned a plantation at Horseshoe Savannah in that parish and another on Charleston Neck.

Whether Culcheth “married up” or just added to his already sizable estate by marrying Mary Butler Elliott, the South Carolina Gazette recorded the following marriage notice:

We hear that Culcheth Golightly, Esq., was married on Monday to Mrs. Mary Elliott, a very agreeable young lady, with a good fortune. (Monday, April 7, 1746)

Culcheth and Mary had two daughters: Dorothy (1747) and Mary (1748). Culcheth’s daughters, however, would grow up without their father for he died in 1749. An interesting notation on one family tree indicates: “Poisoned By Slaves, Oligarchs Charleston South Carolina”. A search yielded no further information, but if true it would surely be an interesting story.

He died on December 14, 1749 and his will, proved on March 18, 1756, left £1,000 sterling to Mary and each of his daughters when they turned twenty-one or were married, “or within 12 months after Wife shall marry again and use of household stuff during time she is a Widow” (Mary remarried in 1759). His wife and children would have been well-cared for given his sizable estate.

One story by C. Irvine Walker in his book The Romance of Lower Carolina provided the following on Mary Golightly’s (daughter) marriage:

About 1765, Miss Golightly, the daughter of an English family now extinct in Carolina, was quite a belle. The following is one of the romantic stories that used to be told, as an instance of how, even in that formal age, “Love would find out the way.” Her family was averse to the man of her heart, Mr. Huger; why, it was not clear, for though not a rich man, was of high position and lofty character. So, Miss Golightly, one night at a ball, picked up a straw hat which chanced to be lying on a bench, and with no more preparation stepped out of the long window into the garden and ran away to be married. The adventurous bride did not live long, but died, leaving one son.

Mary’s husband served during the Revolutionary War as a major and was killed in Charlestown in 1779. Dorothy Golightly married William Henry Drayton. Drayton, a member of the Continental Congress, was one of the first South Carolinians to speak out in favor of breaking with England. He had been appointed as the first chief justice of South Carolina and died in Philadelphia in 1779, having served sixteen months in the Second Continental Congress. Their son, John, later became Governor of South Carolina from 1800-1802 and again from 1808-1810.

One other unusual Golightly forename I ran across was Avoid Golightly, born on January 2, 1925 to Luther and Odell Berry Golightly in Choctaw County, Oklahoma. He was a World War II Navy veteran who died on May 30, 1980 in Paris, Texas. It would have been interesting to know how he came by the name “Avoid” but research didn’t produce any further information.

Speaking of unusual names, be sure and checkout the next two or three weeks of Tombstone Tuesday articles. I found several unusual and unique names in a Johnson County, Tennessee family with interesting histories. This Tuesday will feature an article on “The Ocean Sisters” – stay tuned!

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Feisty Females: Alice Harrell Strickland

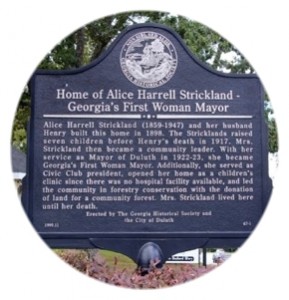

Her campaign slogan in 1921, just one year after women were granted the right to vote, was “I will clean up Duluth and rid it of demon rum.” She had been compelled into the race for mayor of Duluth, Georgia that year, having been a strong advocate for women’s suffrage in the years leading up to the amendment’s passage, and as an active participant in her city’s civic affairs. She would win and become the first female mayor ever elected in the state of Georgia.

Her campaign slogan in 1921, just one year after women were granted the right to vote, was “I will clean up Duluth and rid it of demon rum.” She had been compelled into the race for mayor of Duluth, Georgia that year, having been a strong advocate for women’s suffrage in the years leading up to the amendment’s passage, and as an active participant in her city’s civic affairs. She would win and become the first female mayor ever elected in the state of Georgia.

Alice Harrell Strickland was born on June 24, 1859 to parents Newton and Mary Ellender (Harris) Newton in Forsyth County, Georgia. Her grandparents, Edward and Nancy Strickland Harrell, were some of the original settlers of Forsyth County. Born about two years before the start of the Civil War, Alice was born in an era when young women would have been bred to be Southern belles or “plantation ladies.”

On November 10, 1881, Alice married her cousin Henry Strickland, Jr., a Duluth lawyer and businessman. In the early 1800’s the town was named Howell’s Cross Roads for early settler Evan Howell. This was also the time when the Stricklands, among others, moved to the area. Howell ran a plantation and cotton gin and became the town’s first successful merchant.

On November 10, 1881, Alice married her cousin Henry Strickland, Jr., a Duluth lawyer and businessman. In the early 1800’s the town was named Howell’s Cross Roads for early settler Evan Howell. This was also the time when the Stricklands, among others, moved to the area. Howell ran a plantation and cotton gin and became the town’s first successful merchant.

Years later his grandson Evan P. Howell encouraged the construction of a railroad system that would stretch to Duluth, Minnesota. After Congress approved the financing, the town was renamed Duluth. By the 1880’s Duluth had become a hub for the cotton industry and was also, unfortunately, known for drunken brawls and knife fights.

The Methodist Church had been founded in 1871 and Alice joined the church and the Duluth Civic Club. She and Henry had seven children: Henry, Jr., Newton Harrell, Glenn Beauregard, Anna May, Susan, Charles Edward and Ellyne Elizabeth. All their children attended college and “showed signs of their mother’s pioneering spirit and courage,” according to Georgia Women of Achievement.

In 1898 the Stricklands built a three-story home for their large family. Throughout the late nineteenth century and into the early 1900’s Alice remained active in civic affairs as a member of the Duluth Civic Club. Henry died at the age of 55 following an extended illness of several months. After returning from an operation he underwent in Baltimore, he suddenly passed away on June 4, 1915.

In 1898 the Stricklands built a three-story home for their large family. Throughout the late nineteenth century and into the early 1900’s Alice remained active in civic affairs as a member of the Duluth Civic Club. Henry died at the age of 55 following an extended illness of several months. After returning from an operation he underwent in Baltimore, he suddenly passed away on June 4, 1915.

Alice had never attended college and had remained at home raising her children throughout the years of their marriage. At the time of Henry’s death, two of their children, Charles and Ellyne, remained at home. Charles and Newton later served in World War I — Charles as a private in the 464th Engineers and Newton as an Army captain (promoted to major), both returning to Georgia in 1919.

Undeterred by her lack of professional skills, Alice immersed herself further in civic affairs. During her tenure as president of the Duluth Civic Club, she opened the second floor of her home as a clinic where children were treated for whooping cough, diphtheria and surgically for tonsillitis.

She was considered a “progressive” who was also an ardent conservationist. At one point, Alice challenged the power company who came to erect power lines across her land. “With a shotgun in her hands, she blocked the way of power company workers, keeping them from placing lines across her land.” (Georgia Women of Achievement) She later donated a portion of her land for the purposes of preservation and recreation to the town of Duluth.

The issue of women’s rights was being hotly debated, and on July 8, 1919 the Atlanta Constitution reported that Alice Strickland spoke out strongly in favor of passage of the so-called “Susan B. Anthony Amendment.” Her appeal was made on behalf of not only city women but those who lived in rural areas. She was agitated by the Jackson amendment which had blocked the amendment’s passage in the Georgia legislature, prompting her to demand: “Where is this man Jackson? I want to see him.”

Although the amendment’s defeat was a narrow one in the legislature, Georgia politicians boasted about being the first state to reject it. However, it was for naught because the 19th Amendment passed nationally and women were granted the right to vote in 1920. Alice Strickland must have seen this as her opportunity to make a difference and contribute even more to her community.

In 1921, at the age of sixty-two, she decided to run for mayor of Duluth. According to Georgia Women of Achievement, she campaigned in a politically hostile environment, yet won the election. She made history as the first female mayor ever elected in the state of Georgia. She was fearless but fair and “could not be hoodwinked in the execution of her duties.” (Forsyth County: History Stories, p. 77). True to her campaign promises, she pursued and prosecuted bootleggers in an effort to clean up her community and improve its reputation.

After her term as mayor , Alice continued to live in her family home until her death on September 8, 1947. Over a century after its construction, the home was placed on the Georgia Register of Historical Places in 1999. In 2002, Alice Harrell Strickland was designated as a Georgia Woman of Achievement – feisty like another Georgian female of note and recently profiled here, Nancy Morgan Hart.

, Alice continued to live in her family home until her death on September 8, 1947. Over a century after its construction, the home was placed on the Georgia Register of Historical Places in 1999. In 2002, Alice Harrell Strickland was designated as a Georgia Woman of Achievement – feisty like another Georgian female of note and recently profiled here, Nancy Morgan Hart.

Ninety-seven years and one day ago, on August 28, 1917, women suffragists and activists picketed President Woodrow Wilson, demanding the right to vote. Three years later, on August 26, 1920, their demands were met when the 19th Amendment was ratified by a majority of states.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!