Wild West Wednesday: The Ruby Murders

In 1914 the Ruby Mercantile was sold by Julias Andrews to Philip Clarke, who moved his family to Ruby and built a bigger store up on a hill.

In 1914 the Ruby Mercantile was sold by Julias Andrews to Philip Clarke, who moved his family to Ruby and built a bigger store up on a hill.

The Clarke family soon discovered the dangers of living in Ruby with its proximity to the Mexican border and the presence of bandits in the area. According to Legends of America, store owner Philip Clarke and his wife kept guns in every room of their home and store. Clarke later moved his wife and children to a nearby town while he continued to operate the mercantile.

By 1920 Clarke had purchased substantial acreage and cattle in the area and sold his store to John and Alexander Fraser. The Fraser brothers were warned about Mexican bandits – to be forewarned was to be forearmed. They may not have heeded Clarke’s warning, however, because on February 27, 1920 both were found shot inside their store. Alexander had been shot dead in the back and head and John, still alive with a shot to his left eye, died five hours later.

By 1920 Clarke had purchased substantial acreage and cattle in the area and sold his store to John and Alexander Fraser. The Fraser brothers were warned about Mexican bandits – to be forewarned was to be forearmed. They may not have heeded Clarke’s warning, however, because on February 27, 1920 both were found shot inside their store. Alexander had been shot dead in the back and head and John, still alive with a shot to his left eye, died five hours later.

This article is no longer available for free at this site. It was re-written and enhanced (entitled “Mining and Murder”) with sources and has been published in the March 2018 issue of Digging History Magazine. Should you prefer to purchase the article only, contact me for more information.

This article is no longer available for free at this site. It was re-written and enhanced (entitled “Mining and Murder”) with sources and has been published in the March 2018 issue of Digging History Magazine. Should you prefer to purchase the article only, contact me for more information.

I invite you to check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

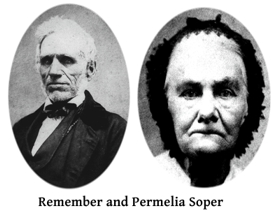

Tombstone Tuesday: Remember Elijah Soper

Remember Elijah Soper was born on May 4, 1794 in Milton, Chittenden County, Vermont to parents Mordecai and Naomi (Owen) Soper. According to The New Soper Compendium by Earl Soper, Mordecai’s place of birth is disputed – some believe he was born in England while others believe he was born in Connecticut in 1746.

Remember Elijah Soper was born on May 4, 1794 in Milton, Chittenden County, Vermont to parents Mordecai and Naomi (Owen) Soper. According to The New Soper Compendium by Earl Soper, Mordecai’s place of birth is disputed – some believe he was born in England while others believe he was born in Connecticut in 1746.

Mordecai married Naomi on April 4, 1770 in Salisbury, Connecticut. His residence was recorded later as “Nine Partners” in Dutchess County, New York, where Mordecai and Naomi lived a short time before settling in Poultney, Vermont in 1771. He served in the Revolutionary War and returned to Poultney then later moved to Milton. There he took the Freedman’s Oath on May 3, 1787 and raised his large family. Remember was the ninth child of thirteen.

Remember served in the War of 1812 as a Captain, and according to the Portrait and Biographical Album of Champaign County, Illinois (PBACC), was present at the battle of Plattsburg, “being in one of the volunteer corps, he was the means of saving the regular troops from defeat. His coolness and bravery inspired his men with courage to rush upon the enemy and put them to flight.”

Remember served in the War of 1812 as a Captain, and according to the Portrait and Biographical Album of Champaign County, Illinois (PBACC), was present at the battle of Plattsburg, “being in one of the volunteer corps, he was the means of saving the regular troops from defeat. His coolness and bravery inspired his men with courage to rush upon the enemy and put them to flight.”

His service was lauded in PBACC, stating that during the battle of Plattsburg “the movements of the volunteer troops commanded by Capt. Soper were so regular and precise that the British mistook them for reinforcements from the regular service, and withdrew from their position, abandoning the attack of the fort.” Captain Remember Elijah Soper, “although at the front with his men, escaped without a wound.”

Remember received a pension and a bounty of one hundred sixty acres of land. He returned home to Vermont and married Permelia McNall in 1819. Their first child Harriet died at the age of one month in 1820, followed by Adeline (1821), Julia; Amasa (1826-1827); Orange Phelps (1828); Eveline (1830); Rachel (1833); and Milton Hubble (1836).

An “R.E. Soper” was enumerated in Franklin County, Vermont in 1840 and in 1847 the family had migrated to Benton, Lake County, Illinois. The county was just south of Wisconsin’s border and near the shoreline of Lake Michigan. His son Orange married Jerusha Abels in Michigan, but returned to Vermont around 1863 with Remember and Permelia.

Jerusha died in 1865 and Orange married Laura Harrington in 1867, then returned to Illinois in 1868. His brother Milton had accompanied the family back to Vermont in 1863, but like Orange moved back to Illinois in 1868. Their daughters married and one migrated west to Wisconsin. Orange migrated the farthest west to South Dakota where he died in Watertown (date unknown).

A little more history on the brothers was found in the Portrait and Biographical Album of Champaign County, Illinois. Milton was remembered as a “gentleman of education and refined tastes who has made the most of his opportunities in life.” He was a highly respected member of the Harwood Township farming community. At the age of sixteen he had entered Waukegan Academy and then attended Lawrence University in Appleton, Wisconsin. Thereafter he matriculated at the University of Michigan, graduated with honors and returned home to find Remember in ill health.

Milton had been hired to superintend the public schools in Memphis, Tennessee, but cancelled his plans and returned to Vermont with Remember and Permelia. The timing was fortuitous since the Civil War was still being fought in that part of the South. Even though Milton had desired at one time to pursue the field of medicine, or perhaps a military career, he put aside those dreams and accompanied his parents home to Vermont.

Instead, he purchased a farm in Franklin County and worked with his father for four years. He and Orange made plans to establish a sheep ranch in southwest Missouri and began the search for land. Apparently it was a little too far south for their tastes: “They looked over the country and found a suitable location, but also found that an ultra Yankee had very little to encourage him in settling there.” Perhaps the deep-seated wounds of war were yet too fresh.

Milton instead returned to Illinois, first purchasing over five hundred acres of speculative land from the Illinois Central Railroad Company. After selling the majority of it he established his own “beautiful farm of 240 acres, with a handsome modern residence, a good barn and all other buildings necessary for the shelter of stock and the storage of grain.” The farm was one of the finest and Milton one of the most esteemed members of the community.

After returning to Vermont in 1863 due to ill health, Remember spent the remainder of his life there. He passed away on November 4, 1872 in Fairfax, Franklin County. Permelia passed away on May 1, 1878. Both are buried in the Miltonboro Cemetery in Chittenden County.

What caught my attention about this story was the name “Remember Elijah” where did that come from? I had seen a list of the children of Mordecai and Naomi and noticed they had a son named Elijah born in 1773 and then in 1794 Remember Elijah was born. Why two sons named Elijah? According to family historians, the first Elijah drowned when his canoe overturned in the Lamoille River. To remember Elijah, they named their next son “Remember Elijah”.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Surname Saturday: Blackwell

Blackwell

Sources agree that the Blackwell surname was a locational name, a place in the counties of Derbyshire, Durham and Worcestshire. It was an ancient surname, traced back to Olde English and Anglo-Saxon orgins.

The name was recorded in the Saxon Cartularium of Durham in 964 as “Blacwaelle”, according to the Internet Surname Database. An instance of the name was also recorded in Derbyshire as “Blacheuuelle” in the 1086 Domesday Book.

This locational name meant “black stream”, stemming from the Olde English word “blaec” which meant “dark-colored”, likely referring to the color of the water. The name may have also referred to someone who lived next to a “black stream”.

This locational name meant “black stream”, stemming from the Olde English word “blaec” which meant “dark-colored”, likely referring to the color of the water. The name may have also referred to someone who lived next to a “black stream”.

The spelling variations of this surname are varied and numerous, including Blackwell, Blackwall, Blackwill, Blakewell, Blakewill, Blaikewall, Blakwill, Blackville, Plackwell, Plakewell, Plackville, Blatswill and more.

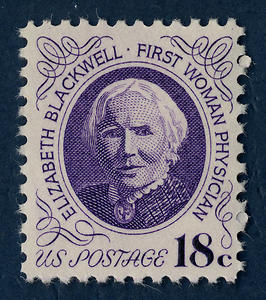

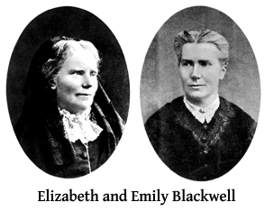

Yesterday, I wrote about the early life of Elizabeth Blackwell, America’s first female medical school graduate. Following is the conclusion of her amazing story. If you missed Part I, you can read it here.

Elizabeth Blackwell: Medical School and Beyond

“With an immense sigh of relief and aspiration of profound gratitude to Providence”, Elizabeth Blackwell accepted Geneva Medical College’s invitation to enroll. Within days she was on her way to western New York. Upon her arrival she was interviewed by the dean of the college and assigned as student No. 130 in the medical department.

Although the medical program was short in comparison to today’s requirements, the task ahead was nonetheless daunting. One of the professors read her letter of introduction from Dr. Warrington, the Quaker who had advised her to give up, and then Elizabeth entered the lecture hall.

She later surmised the professor was reminding his students that a lady would grace their presence. Apparently it wasn’t uncommon in that day for students to make all sorts of crude remarks and jokes aimed at their professors. As the story goes, Elizabeth’s presence in the classroom made it more likely that her male counterparts would behave themselves.

While gradually being accepted by the faculty and her fellow students, the townspeople, specifically the women folk, weren’t as approving. In her autobiography, Pioneer Work in Opening the Medical Profession to Women, Elizabeth remarked:

Very slowly I perceived that a doctor’s wife at the table avoided any communication with me, and that as I walked backwards and forwards to college the ladies stopped to stare at me, as at a curious animal. I afterwards found that I had so shocked Geneva propriety that the theory was fully established either that I was a bad woman, whose designs would gradually become evident, or that, being insane, an outbreak of insanity would soon be apparent.

Still, however, she discovered that she was barred from certain lectures or demonstrations which were deemed too delicate for woman’s sensibilities – the reproductive anatomy lecture would not be appropriate for a lady. Elizabeth disagreed, argued her case and won the support of her fellow students.

Following her first term Elizabeth began searching for a hospital or institution where she could conduct her summer studies in practical medicine. She returned to Philadelphia and decided to study at the Blockley Almshouse. Her first assignment took her to the third floor, the women’s syphilitic department, “the most unruly part of the institution.”

The director thought her presence might have a positive effect on the “very disorderly inmates.” Instead, she was thought of as a curiosity. She made the acquaintance of the resident matron whose appearance belied her gruff mannerisms in dealing with patients; Elizabeth referred to her as Mrs. Beelzebub. She was, however, enraptured with the head physician, Dr. Benedict, whose patient and kind ministrations to his terminally ill patients touched Elizabeth.

The Irish potato famine brought scores of immigrants, many who had been afflicted with famine fever while making their way across the seas. Blockley was overwhelmed with the epidemic, but proved a valuable lesson for Elizabeth — she used her experiences and observations of that summer to later write her graduate thesis on typhus.

Elizabeth returned to school following her summer practicum and renewed her determination to complete her course of study. By this time she was more at ease and confident in her own capabilities, and even though she could have concurrently pursued a social life, she chose not to do so. In her words, “I lived in my room and my college, and the outside world made little impression on me.”

By mid-January of 1849 she was preparing to sit for her exams. On January 19 she wrote that she had passed her final examinations with flying colors, first in her class. Perhaps realizing they were about to witness a momentous event in history, her fellow students greeted her with applause. In four days she would become the first women in U.S. history to receive a medical degree.

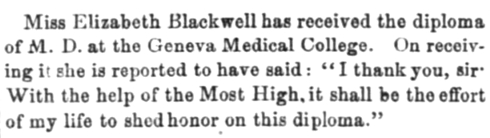

With thankfulness to God on her mind, Elizabeth entered the Presbyterian church where the graduation ceremony was held on January 23. After all other students had received their degrees, Elizabeth was called to the platform. After receiving her diploma from the school’s president, she addressed him, “Sir, I thank you; it shall be the effort of my life, with the help of the Most High, to shed honour on my diploma.”

Keenly aware of her momentous accomplishment, Elizabeth knew that it was only the first step. She returned to Philadelphia for a short time, intending to continue her medical studies. Instead, at the invitation of a cousin, she traveled abroad in April and studied in Paris and London. Her colleagues and advisers had encouraged her specifically to consider studying in Paris where opportunities for women were more readily available. In June her post-graduate work continued as she accepted a position in Paris at its maternity hospital, La Maternité.

She began working in the field of obstetrics and had planned to become a surgeon. However, in November of 1849 while treating a baby’s eye infection, she contracted what was most likely gonorrhea (which was probably passed to the baby as it passed through the birth canal) and lost sight in her left eye. She would never become a surgeon.

After completing her term of study at La Maternité, and now blind in one eye, Elizabeth traveled around Europe for a time. Her studies at St. Bartholomew’s in London, however, presented a challenge as she noted in journal entries and letters to her family. One professor in charge of Midwifery and the Diseases of Women and Children had basically written her off, politely informing her of his disapproval of women in medicine.

While in London, one of her more pleasant experiences was a social one, making the acquaintance of Miss Florence Nightingale (although they later had a falling out). By May of 1851 it was time to consider whether it would be more profitable for her to remain in England or return to America. Encouraged by attempts in Philadelphia and Boston to found schools for women to pursue medical careers, Elizabeth finally departed England in July of 1851.

Elizabeth chose to begin her formal practice in New York, but the first seven years were “uphill work”. As a solo practitioner, with a largely empty waiting room, she began to feel isolated and in 1853 established a dispensary among the New York’s poor, near Tompkins Square in Manhattan.

In 1857 the dispensary expanded into the New York Infirmary for Women and Children. The third woman in U.S. history to receive a medical degree, her sister Emily, joined the practice. Emily’s presence lifted her spirits, her “working powers more than doubled.” While Elizabeth focused on the practice of obstetrics and gynecology, Emily handled the surgical practice.

Still, the hospital caused a stir because it was one thing for a woman to receive a medical degree, but yet another to found a hospital and purport to train other women in the practice of medicine. They had been warned that no one would lease them a facility, and they would be looked upon with suspicion purely because they were female doctors. The critics believed that without male doctors at such a facility there was no way the women could control the situation should some incident or accident occur.

Elizabeth and Emily plowed ahead, determined that their hospital would be staffed entirely by women. Perhaps to assuage the public’s doubts, the board of physicians which oversaw their operations was entirely male, all supporters of the Blackwell sisters and their enterprise.

Elizabeth traveled throughout Europe and immersed herself in social reform, specifically in areas concerning women’s rights, health issues, medical education for women and more. She traveled back and forth to London several times in the 1860’s and 1870’s, and in 1874 helped establish the London School of Medicine for Women.

She and Emily had experienced a rift in their relationship, disagreeing over the management of the hospital and medical college. In 1869 she left America behind, having become somewhat disenchanted with the women’s medical movement there, and returned to England. She worked for a time at the London School of Medicine for Women but was gradually pushed aside as a physician. In 1877 she left the active practice of medicine and continued to push for social reforms.

Like her five sisters, Elizabeth never married. She simply had no use for, nor the time to pursue a marriage relationship. She had always possessed a strong personality and could be quite critical in her views of others.

Her memoirs were published in 1895, and Elizabeth remained a professor of gynecology until 1907 when she fell down a flight of stairs. The accident left her not only physically challenged, but mentally disabled as well. On May 31, 1910 she suffered a stroke at her home in Sussex and died at the age of eighty-nine.

Her memoirs were published in 1895, and Elizabeth remained a professor of gynecology until 1907 when she fell down a flight of stairs. The accident left her not only physically challenged, but mentally disabled as well. On May 31, 1910 she suffered a stroke at her home in Sussex and died at the age of eighty-nine.

Her sister Emily died four months later in Maine on September 7 at the age of eighty-three. Their pioneering work had paved the way for wider acceptance of women in medicine. In 1915 the American Medical Association admitted its first female members.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Feisty Females: Elizabeth Blackwell (Part I)

On January 23, 1849, Elizabeth Blackwell became the first woman in U.S. history to receive a medical degree at New York’s Geneva Medical College. Today, a momentous first of any kind would be trumpeted all over the world in a series of instant tweets. In 1849 it registered barely a mention six days later in New York’s Evening Post, squeezed between random news tidbits like “The harbor is clear of floating ice“ and “Capital punishment for murder in the first degree has been restored in Michigan.”

On January 23, 1849, Elizabeth Blackwell became the first woman in U.S. history to receive a medical degree at New York’s Geneva Medical College. Today, a momentous first of any kind would be trumpeted all over the world in a series of instant tweets. In 1849 it registered barely a mention six days later in New York’s Evening Post, squeezed between random news tidbits like “The harbor is clear of floating ice“ and “Capital punishment for murder in the first degree has been restored in Michigan.”

This article has been removed from the web site, but will appear (rewritten, complete with footnotes and sources) in a future issue of Digging History Magazine.

This article has been removed from the web site, but will appear (rewritten, complete with footnotes and sources) in a future issue of Digging History Magazine.

I invite you to check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Ghost Town Wednesday: Ruby, Arizona

According to Southern Arizona Guide, this is one of the best preserved ghost towns in Arizona. Off the beaten track and twelve miles south of Arivaca, visitors are warned to NOT rely on their GPS to find Ruby. The Spaniards discovered minerals there in the 1700’s but only mined a short time before moving on.

According to Southern Arizona Guide, this is one of the best preserved ghost towns in Arizona. Off the beaten track and twelve miles south of Arivaca, visitors are warned to NOT rely on their GPS to find Ruby. The Spaniards discovered minerals there in the 1700’s but only mined a short time before moving on.

Mining was revived when Charles Poston and Henry Ehrenberg found the old Spanish mines, started digging and found rich veins of gold and silver. Gold and silvers finds like that always brought more miners seeking their fortune, but it took until the 1870’s before prospectors came en masse to the area due to the strong Apache presence. When they finally came, “Montana Camp” was setup, so-called because it lay at the foot of Montana Peak.

Mining was revived when Charles Poston and Henry Ehrenberg found the old Spanish mines, started digging and found rich veins of gold and silver. Gold and silvers finds like that always brought more miners seeking their fortune, but it took until the 1870’s before prospectors came en masse to the area due to the strong Apache presence. When they finally came, “Montana Camp” was setup, so-called because it lay at the foot of Montana Peak.

This article is no longer available for free at this site. It was re-written and enhanced (entitled “Mining and Murder”) with sources and has been published in the March 2018 issue of Digging History Magazine. Should you prefer to purchase the article only, contact me for more information.

This article is no longer available for free at this site. It was re-written and enhanced (entitled “Mining and Murder”) with sources and has been published in the March 2018 issue of Digging History Magazine. Should you prefer to purchase the article only, contact me for more information.

I invite you to check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Tombstone Tuesday: Dr. Jesse Lovask Green (His Quiver Was Exceedingly Full)

Jesse Lovask Green was born on February 1, 1802 to parents Amos and Elizabeth (Searcy) Green in Rutherford County, North Carolina. Amos and Elizabeth were the parents of several children, possibly as many as twelve or thirteen. In 1810 there were eight household members enumerated in Amos Green’s household and in 1820 there were thirteen.

Jesse Lovask Green was born on February 1, 1802 to parents Amos and Elizabeth (Searcy) Green in Rutherford County, North Carolina. Amos and Elizabeth were the parents of several children, possibly as many as twelve or thirteen. In 1810 there were eight household members enumerated in Amos Green’s household and in 1820 there were thirteen.

Although no slaves had been enumerated in the two previous censuses, in 1830 the Amos Green family possessed three slaves – two females between 10 and 23 and one male under 10. However, by that time Jesse and his wife Mary Ann had migrated to Cherokee County, Georgia, arriving there in 1824. There Jesse purchased land along the Etowah River and settled among the Cherokee Indians.

The area where Jesse and Mary Green settled was home to several tribes at various times in history and place names in that region reflect that culture. However, by the end of the 1830’s Cherokee Indians were expelled from their native lands and removed to Indian Territory, later to be called Oklahoma. According to the Georgia Encyclopedia, the removal “was a product of the demand for arable land during the rampant growth of cotton agriculture in the Southeast, the discovery of gold on Cherokee land, and the racial prejudice that many white southerners harbored toward American Indians.”

It’s presumed that Jesse had a friendly relationship with his Cherokee neighbors, since according to family historians he used herbs and remedies imparted to him by the Indians. Some family researchers believe, although they have no solid proof, that Jesse may have been married first to an Indian woman, presumably in North Carolina before he migrated to Georgia. While Jesse was enumerated in 1850 and 1860 as a “physician” it is unclear whether he had received conventional medical training or had merely observed the practices of his Cherokee neighbors.

It’s presumed that Jesse had a friendly relationship with his Cherokee neighbors, since according to family historians he used herbs and remedies imparted to him by the Indians. Some family researchers believe, although they have no solid proof, that Jesse may have been married first to an Indian woman, presumably in North Carolina before he migrated to Georgia. While Jesse was enumerated in 1850 and 1860 as a “physician” it is unclear whether he had received conventional medical training or had merely observed the practices of his Cherokee neighbors.

Jesse and Mary Green are believed to have had eleven or twelve children before Mary passed away on March 23, 1850 in Ball Ground, Cherokee, Georgia. The 1850 census, recorded five months following Mary’s death, indicates that Jesse was a widower with nine children living in his home: Lewis (25); Louisa (18); Lucinda (16); William (13); Juliann (11); Mary Ann (9); Joseph Hanson (7); Jasper (5); and Elizabeth (3). Their daughter Sarah (b. 1827) had married Edward Bagby in 1848.

Following Mary’s death, Jesse married Louisa Johnston in 1851 and she bore him several more children: Sophronia (1852); Emeline (1853); Henry (1855); Margaret (1856); Louvenia (1858); Virgil (1860); Jesse (1863); Lisena (1864); Martha Ellen (1865); Amanda (1869) and Delia (1875). There may have been a contagious illness in the family, years after Jesse’s death, when Delia and Virgil both died in May of 1889.

In fact, Jesse died on April 16, 1875 just a few months before Delia was born on July 1, and he was buried in the same cemetery as Mary Ann, and later, several of his children. Louisa was enumerated in 1880 as a widow and the head of her household. In 1900 she was living with her son Jesse B. Green and his family before they moved to Grayson County, Texas between 1900 and 1910. Louisa died there on September 3, 1905 and is buried in the Christian Chapel Cemetery. Inscribed on her tombstone she is noted as the wife of Dr. Jesse Green, late of Georgia.

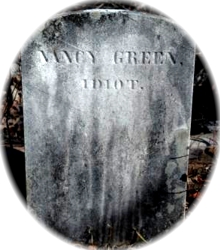

While researching Jesse Green and his family, I stumbled on a bit of history which provides insight on how the less fortunate, especially mentally handicapped individuals, were regarded by some in those days. Amos and Elizabeth Green had migrated to Cherokee County between 1830 and 1840. In 1850, two individuals, presumably two of their children, were residing in the same household: Oliver P. (30) and Nancy (27).

Oliver and Nancy apparently had a mental handicap as they were both noted in column 13 of the census form as “idiot”. When Nancy died is unclear, however, because there doesn’t appear that a date was ever inscribed on her tombstone – merely the notation “IDIOT”. How sad is that?

The 1850 census was the first one that all members of the household were enumerated separately and the census taker was required to inquire as to the full health of each occupant. In 1850 the choices in column 13 of the form were “dumb”, “blind” or “idiotic” (left blank if “normal” it appears).

The 1850 census was the first one that all members of the household were enumerated separately and the census taker was required to inquire as to the full health of each occupant. In 1850 the choices in column 13 of the form were “dumb”, “blind” or “idiotic” (left blank if “normal” it appears).

In 1860 and 1870 the questions were the same, but in 1880 there were separate schedules for: Insane (Schedule 2); Idiots (Schedule 3); Deaf-Mutes (Schedule 4); Blind (Schedule 5); Homeless Children (Schedule 6); Prisoners (Schedule 7); and Pauper and Indigent (Schedule 7a).

If, for instance, a person was enumerated in 1880 as an “idiot”, you can find additional information about them on Defective Schedule 3. For “idiot”, information such as date of onset, supposed cause and size of head is provided. Interesting, huh?

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Surname Saturday: Ping-Pang-Pung-Pagan-Paine

These surnames emanate from different parts of Scotland, but all are rooted in the personal name Payne. The Old English word “payn” was a name given to a villager or someone who lived in the country.

According to House of Names, the west coast of Scotland and the Hebrides Islands were home to both the Ping and Pang families, while a northern region of Scotland, Dalriada, was home to the Pung and Pagan families. In ancient times it was a Gaelic kingdom which comprised parts of western Scotland and northeastern Ulster in Ireland.

Pagan is noted as a spelling variation of Ping, Pang and Pung, including other spellings such as Paganell, Paganel, Pagnell, Paine, Payne, Pain and others. Immigration records show that some of the Scottish settlers who crossed the ocean to North America went to Canada. And, some who landed in America went north to Canada during the Revolutionary War, considering themselves Loyalists to the King of England.

Pagan is noted as a spelling variation of Ping, Pang and Pung, including other spellings such as Paganell, Paganel, Pagnell, Paine, Payne, Pain and others. Immigration records show that some of the Scottish settlers who crossed the ocean to North America went to Canada. And, some who landed in America went north to Canada during the Revolutionary War, considering themselves Loyalists to the King of England.

Thomas Paine, American patriot and activist, spurred the colonists to revolution with his fiery rhetoric, published in pamphlets such as Common Sense and The American Crisis. Clearly, he was not a fan of the King, and his works were viciously attacked by Loyalists. Surprisingly, some of his works weren’t welcomed by other American revolutionaries. Late in his life John Adams was quoted as saying of Common Sense: “What a poor, ignorant, malicious, short-sighted, crapulous mass.”

After the war, Paine returned to England in 1787 and became involved in yet another revolution – the French Revolution. As an enthusiastic supporter of the French Revolution, he published pamphlets and was given honorary French citizenship (Benjamin Franklin, George Washington and Alexander Hamilton were also so honored).

He eventually found himself on the wrong side of the faction known as the Girondins who wanted to do away with the monarchy. Paine, siding with Louis XVI because he was personally opposed to capital punishment, was arrested and thrown in prison in December of 1793. Claiming that he was an American citizen didn’t help his cause either.

Through a quirk of fate he narrowly missed being executed. The jailer went through the prison and placed a chalk mark on the door of those who were awaiting execution. The mark was placed on the outside, but for some reason Paine’s door was open and the mark was placed on the inside. He was released the following year and remained in Paris until 1802.

In 1796, incensed that George Washington had done nothing on his behalf while imprisoned, he fired off a scathing letter, calling the President of the United States a dishonorable and treacherous man: “The world will be puzzled to decide whether you are an apostate or an impostor; whether you have abandoned good principles or whether you ever had any.”

Paine eventually returned to America, but found himself out-of-favor with many after his recent writings and his very public attack on George Washington. He died on June 8, 1809 and disdained was he in his own country, the Quakers (he was Quaker) wouldn’t allow him to be buried in their graveyard. He was buried near a walnut tree on his farm.

Some newspapers made only a passing mention of his death. The New York Evening Post printed the original obituary, which was then copied by newspapers across the country. One statement summed up widespread American sentiment of Thomas Paine at that point in history: “He had lived long, did some good, and much harm.”

Pings in Pulaski County, Kentucky

My Tombstone Tuesday article this week (read it here if you missed it) was about Iredel and Siotha Ping Wright of Pulaski County, Kentucky. I generally don’t write Tombstone articles about people who are related to me, but Iredel and Siotha lived in the county where many of my ancestors settled. Many distant relatives still live there, and although I’ll probably never meet any of them, I saw names familiar to me when researching these articles.

I thought “Ping” might not break my rule-of-thumb, but as it turns out the Ping family is probably related, at least by marriage in some cases, to at least two of my ancestral lines, Brinson and Earp. It’s quite possible they also married others of my line like the Stogsdills, Chaneys, Alexanders, Fulchers and more. It just fascinates me to no end how, I believe, we are all somehow related to one another. Maybe that’s the way the good Lord intended it, eh?

Research Note: These surnames aren’t exclusively Scottish or English. Ping and Pang are also Oriental or Asian surnames; Pagan (also spelled Pagán) is Hispanic.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

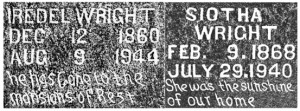

Tombstone Tuesday: Iredel and Siotha Ping Wright

Iredel Wright was born to parents Henry Monroe and Rebecca (Cordell) Wright in December of 1859, according to the 1860 Census, this despite the fact that his tombstone reads December 12, 1860. According to family historians, Henry who was born in 1826 had been adopted by a woman named Elizabeth Wright, so it’s unclear who his parents were, or if in fact their names were also Wright.

Iredel Wright was born to parents Henry Monroe and Rebecca (Cordell) Wright in December of 1859, according to the 1860 Census, this despite the fact that his tombstone reads December 12, 1860. According to family historians, Henry who was born in 1826 had been adopted by a woman named Elizabeth Wright, so it’s unclear who his parents were, or if in fact their names were also Wright.

Henry and Rebecca married in Tennessee and later moved to Pulaski County sometime in the 1850’s and lived there the remainder of their lives. It appears that Henry registered in October of 1863 for service in the Union Army (the record was a bit hard to locate because he was listed as “Henry Right” – beware of bad spellers when you’re looking for long-lost relatives!). Whether he ever served is unclear since his name didn’t appear on an 1883 list of pensioners1, although there is a Henry Wright listed as a member of a Kentucky Union Regiment.2

Pulaski County, according to The Kentucky Encyclopedia (p. 748), had Confederate sympathizers, but the majority of the population were Unionists. Unlike last week’s subject, Simpson Socrates Nix (also a Kentucky resident), the Wrights (and Pings) were on the side of the North. Pulaski County sent twelve hundred men to the Union Army, and one of the worst Confederate defeats in the mountains occurred in the county on January 19, 1862.

Pulaski County, according to The Kentucky Encyclopedia (p. 748), had Confederate sympathizers, but the majority of the population were Unionists. Unlike last week’s subject, Simpson Socrates Nix (also a Kentucky resident), the Wrights (and Pings) were on the side of the North. Pulaski County sent twelve hundred men to the Union Army, and one of the worst Confederate defeats in the mountains occurred in the county on January 19, 1862.

Siotha Ping was born on February 12, 1868 in Pulaski County to parents William Green and Elizabeth Ping. Will was also a veteran of the Civil War, having enlisted sometime in the summer or early fall of 1863. Will’s father Lewis also served and later applied for and received a government pension for his service.

According to family historians, Lewis enlisted as a Private in Company B of the 12th Regiment of the Kentucky Volunteer Infantry for a three-year term on October 12, 1861, and was mustered in on January 30, 1862. Lewis served faithfully until falling ill at Corinth, Mississippi, scene of one of the most devastating defeats for the Confederates in terms of casualties and deaths.

After being transferred to a hospital in Louisville, Kentucky he was mustered out on February 24, 1863. Sometime during his service, Lewis had contracted measles, which along with other diseases like typhoid fever, caused more deaths than battle wounds. As a result, Lewis wasn’t able to perform manual labor for the rest of his life.

Iredel married Siotha Ping on December 28, 1882. Siotha was a couple of months shy of turning fifteen and Iredel had just turned twenty-three. Various family trees record that Matilda Elizabeth Wright was born on October 24, 1882. More children followed, as enumerated in the 1900, 1910 and 1920 censuses: Telia, William, Mary, Maggie, Smith, Millard Fillmore, Esau, and Marion Curry, Alva and Edward Harmon. The 1910 census indicates that Siotha was the mother of eleven children and ten were still living at that time.

On November 25, 1901, Iredel was appointed as U.S. Postmaster for Randall. Sometime between that date and the 1910 census, however, the Wright family moved to Oklahoma. In 1910 they were living in Carr, Tillman County, Oklahoma and in 1920 residing in Grayson, Jefferson County, Oklahoma. However, by 1930 Iredel and Siotha had returned home to Pulaski County and were living with Alva and his family.

On July 29, 1940 Siotha died at the age of seventy-two of kidney disease and hypertension. She and Iredel had been enumerated for the 1940 census in April and he was still farming at the age of eighty. Iredel lived four more years until his death on August 9, 1944 at the age of eighty-four. Iredel and Siotha are buried in the Goodwater Cemetery in Somerset.

I’ve been doing some research of late on my Pulaski County ancestors and had stumbled across some unique names (first and last) – that is, by the way, how I sometimes select subjects for these articles. In researching today’s article, I found a family tree which included Will Ping and interestingly the tree was named “Ping-Stout family tree” which immediately piqued my interest because I have Stout ancestors. In fact, I have recently discovered that I have three Stout cousins who are also members of our local genealogical society.

Sure enough, this person and I share ancestors, Richard and Penelope Stout of Middletown, New Jersey. Theirs is a fascinating (and in the case of Penelope, harrowing) story which I’ll have to write about sometime – stay tuned.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Motoring History: Ford 999 Ices A Record

Granted, the record didn’t last for long, but on this day in 1904 Henry Ford set a land speed record on the frozen surface of Lake St. Clair in Michigan. After founding the Detroit Automobile Company in August of 1899, only to have it go under by January 1901, Henry Ford still loved cars and racing. It was time to re-invent himself.

Granted, the record didn’t last for long, but on this day in 1904 Henry Ford set a land speed record on the frozen surface of Lake St. Clair in Michigan. After founding the Detroit Automobile Company in August of 1899, only to have it go under by January 1901, Henry Ford still loved cars and racing. It was time to re-invent himself.

In October of 1901 he thought his best chance to restore himself financially was to race and win against the best race car driver in America at the time, Alexander Winton. Winton’s cars were more advanced and Henry wasn’t favored to win, but win he did. In the annals of Ford Motor Company history it is referred to as “The Race That Changed Everything”. You can read an article from last year here.

In October of 1901 he thought his best chance to restore himself financially was to race and win against the best race car driver in America at the time, Alexander Winton. Winton’s cars were more advanced and Henry wasn’t favored to win, but win he did. In the annals of Ford Motor Company history it is referred to as “The Race That Changed Everything”. You can read an article from last year here.

This article is no longer available at this site. However, it will be enhanced and published later in a future issue of Digging History Magazine, our new monthly digital publication available by individual purchase or subscription. To see what the magazine is all about you can preview issues at our YouTube Channel. Subscriptions are affordable, safe and easy to purchase and the best deal for getting your “history fix” every month.

This article is no longer available at this site. However, it will be enhanced and published later in a future issue of Digging History Magazine, our new monthly digital publication available by individual purchase or subscription. To see what the magazine is all about you can preview issues at our YouTube Channel. Subscriptions are affordable, safe and easy to purchase and the best deal for getting your “history fix” every month.

I invite you to check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Surname Saturday: Reeve (and America’s first law school)

This English surname is occupational, an official one for a steward or bailiff. According to House of Names, the name can be traced back to the Anglo-Saxon tribes of Britain, and one that was given to the member of a family who “worked as a local representative of a lord.” The surname is derived from the Middle English word “reeve” which was derived from an Old English word, “(ge)refa”.

Early records show Sampson le Reve on the Hundred Rolls of Suffolk in 1273 and James le Reve appeared in the Calendar of Letter Books (London, 1281). Spelling variations include: Reeve, Reeves, Reve, Reave, Reaves, Rives, Reavis and more.

Early records show Sampson le Reve on the Hundred Rolls of Suffolk in 1273 and James le Reve appeared in the Calendar of Letter Books (London, 1281). Spelling variations include: Reeve, Reeves, Reve, Reave, Reaves, Rives, Reavis and more.

In researching the Reeve surname I came across an early American with an interesting forename I had never seen before. As it turns out, he made quite an impact on American history and the shaping of our judicial system.

Tapping Reeve

Although I saw one reference to his name being “Tappan”, most sources have his name as “Tapping”, his mother’s surname. Tapping was born on October 17, 1744 to parents Reverend Abner and Deborah (Tapping) Reeve in Fire Place (now Brookhaven), Suffolk, New York.

Tapping graduated from the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University) in 1763, and while continuing his post-graduate education was the headmaster of a school in Elizabeth, New Jersey. During that time he was also hired as the private tutor of the orphaned children of Reverend Aaron Burr, Sr. and his wife Esther Edwards Burr.

Reverend Burr’s children, Sally and Aaron (who later served as the third Vice President of the United States under President Thomas Jefferson), were under his tutelage for several years. Tapping fell in love with Sally, but because their age difference was so great and he hadn’t yet established himself financially, he was refused permission to marry her.

Tapping went to Hartford, Connecticut (he had received his Masters from the College of New Jersey in 1766) and read the law under Judge Jesse Root. With his commitment to a promising career as a jurist, his request to marry Sally was then granted. On June 4, 1771 the couple married. The following year Tapping received his credentials and the couple moved to Litchfield, Connecticut where he began his law practice.

With the success of his law practice, Tapping was able to build a home for Sally across the street from Governor Oliver Wolcott. In 1774, his brother-in-law Aaron moved to Litchfield so he could study law with Tapping. However, revolution was more on the mind of young Aaron when he departed the following year to join the Continental Army.

Tapping’s poor health prevented him from being an active participant in the Revolutionary War, although he was fervently patriotic. In 1776 he undertook the task of recruiting volunteers for the Continental Army and was later commissioned as an officer (ceremonially only it appears), accompanying his recruits to New York and then returning to Connecticut to care for ailing wife Sally.

Tapping’s skills as a lawyer brought other young men to study under his tutelage like Aaron Burr had before the war. Apprenticing under another attorney or judge was common practice, but as his reputation spread and brought more students Tapping decided to develop a series of lectures that would help his students pass the bar exam and practice law.

At this point in American history there were no colleges or universities which offered law degrees. Thus, when Tapping began to develop curriculum the process became more formalized. At first, students met in his law office, but when the numbers increased dramatically he built a one-room building next door to his home.

After an eighteen-month course of lectures, the young men were well-prepared to succeed in the practice of law, should they pass the bar exam. Students took detailed notes in their classes then later re-copied them and bound them into leather volumes, forming the basis for their own personal “law library”. For the remainder of their careers as lawyers, these students possessed valuable reference material to guide them.

Tapping Reeve, of course, practiced law himself in addition to molding the minds of young men. One of his most prominent cases led to the abolition of slavery in Massachusetts (Brom & Bett vs. Ashley). He was joined by another prominent attorney, Thomas Sedgwick, and together they were successful in helping their client Elizabeth Freeman (Bett), a slave, secure her freedom. The basis of their argument was a phrase contained in the Massachusetts Constitution, written in 1780, which stated “all men are born free and equal.”

Tapping Reeve, of course, practiced law himself in addition to molding the minds of young men. One of his most prominent cases led to the abolition of slavery in Massachusetts (Brom & Bett vs. Ashley). He was joined by another prominent attorney, Thomas Sedgwick, and together they were successful in helping their client Elizabeth Freeman (Bett), a slave, secure her freedom. The basis of their argument was a phrase contained in the Massachusetts Constitution, written in 1780, which stated “all men are born free and equal.”

Graduates of the Litchfield Law School went on to make their own mark on the American judicial system. According to the Litchfield Historical Society, the list of alumni included “two vice-presidents, 101 United States congressmen, twenty-eight United States senators, six cabinet members, three justices of the United States Supreme Court, fourteen governors and thirteen chief justices of state supreme courts.”

Tapping Reeve continued to teach his students until 1798 when he was appointed to sit as Judge of the Superior Court of Connecticut. At that time he hired one of his former students, James Gould, to run the school. He was later appointed to the state supreme court and was named its Chief Justice in 1814, serving just one year in that position before retiring. He died on December 13, 1823.

And that is how the first law school came into existence in America. The one-room school house, the original law school, and Tapping Reeve’s home were given status as National Historical Landmarks in 1965.

Tapping’s father Abner, who although a successful minister and an “extraordinary man” in the words of one biographer, experienced some moral failings. An article about Abner is included in the Early American Faith Special Edition on sale here.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!