Ghost Town Wednesday: Moonville, Ohio

Not only is Moonville, Ohio a ghost town in the classic sense of the term (a once thriving town completely abandoned), stories abound about the haunting of various locales in and around the town.

No one seems to know where the town name originated, although some have theorized folks with the last name of “Moon” lived in the area, or that the railroad named the town in honor of a local grocery store owner. The land upon which the town was built belonged to Samuel Coe. Samuel was born on July 20, 1813 in Pompey, New York to parents Chester and Roxanna Coe. The family eventually migrated to Ohio, where Samuel met and married Emaline Newcomb on August 27, 1836 in the Rome township of Ashtabula County. Soon thereafter the Coes moved to Rue in Athens County.

Samuel’s uncle Josiah Coe had purchased land in that area of southeastern Ohio in 1803 so it’s possible that Samuel already knew of the abundant natural resources. At some point, Samuel purchased 350 acres in the Brown Township near where Moonville would eventually be situated. In the 1850’s, the railroads were beginning to boom and expand westward. One of those railroads, the Marletta and Cincinnati Railroad (M&C) had been experiencing financial difficulties and decided to offer stock subscriptions to encourage property owners to allow M&C track to be routed through their land.

Samuel’s uncle Josiah Coe had purchased land in that area of southeastern Ohio in 1803 so it’s possible that Samuel already knew of the abundant natural resources. At some point, Samuel purchased 350 acres in the Brown Township near where Moonville would eventually be situated. In the 1850’s, the railroads were beginning to boom and expand westward. One of those railroads, the Marletta and Cincinnati Railroad (M&C) had been experiencing financial difficulties and decided to offer stock subscriptions to encourage property owners to allow M&C track to be routed through their land.

Samuel Coe, in entrepreneurial spirit, offered to allow M&C to lay track through his property for free – the caveat being that he would have a railroad at his disposal to haul away the coal on his property to sell to the burgeoning coal markets.

The rail company was not in a great financial position at that time and had already made plans to lay track in another area, but the deal was so enticing that they agreed to Coe’s offer. In approximately 1856 the town of Moonville sprung up as a railroad town, surrounded by coal and clay mining operations. The town was never more than about one hundred residents, but it did have a school, cemetery, post office, store, train depot and a saloon. Homes were built up in the hills and hollows surrounding the town and for awhile the area boomed with mining production – even providing iron ore to build weaponry for the Civil War.

By the late 1880’s the M&C was bought out by the Baltimore & Ohio (B&O) Railroad. The town of Moonville gradually declined as natural mining resources were depleted. In 1947 the last family left the town and today all that remains are building foundations and the nearby Moonville Tunnel, which is the subject of ghost stories and legends.

<Ghost stories here>

The job of brakeman was one of the most dangerous in the railroad business. As the job title implies, they were responsible for helping the train brake, sometimes in precarious situations such as turns and downhill runs. In those railroad boom years, brakeman accidents and deaths were all too common. Some claim that they have seen a “ghost” walking along the tracks and under the tunnel, supposedly a brakeman:

The story of the engineer who died in the head-on collision of his train with another spawned a legend about a ghostly figure walking along the tracks carrying a lantern:

“A ghost (after an absence of one year) returned and appeared in front of a freight at the point where Engineer Lawhead lost his life. The ghost is seen in a white robe and carrying a lantern. “The eyes glistened like balls of fire and surrounding it was a halo of twinkling stars” – Chillicothe Gazette, 17 Feb 1895″

One of the more “colorful” ghost stories is the one about a man named David “Baldie” Keeton . He is said to walk above the Moonville Tunnel and toss rocks and pebbles below. Baldie was 65 years old and his death was of a suspicious nature. He was known as a brawler of sorts and one night he had stopped in at the local saloon on his way home. Trouble ensued and on his way home some have theorized that Baldie was attacked and murdered and perhaps thrown on the tracks where he was run over possibly by several trains … his body horribly mangled. If it was murder, no one ever confessed.

According to a web site devoted to Moonville and its history, there isn’t much left to see at the cemetery. Many head stones are missing (web site says that a custom was to take grave stones and use them for walkways and steps).

Directions to the ghost town of Moonville are here http://www.moonvilletunnel.net/Directions_To_Moonville.htm

should you ever find yourself in southeastern Ohio and up for a ghost hunt.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Tombstone Tuesday: Sylvester (Syl) and Emma Gambllin – Alma, New Mexico

These two gravestones caught my eye. I suspected they were husband and wife, being the only Gamblins in this cemetery. Both Syl (Sylvester) and Emma also lived into their 90s so I’m thinking they must have led full and interesting lives.

These two gravestones caught my eye. I suspected they were husband and wife, being the only Gamblins in this cemetery. Both Syl (Sylvester) and Emma also lived into their 90s so I’m thinking they must have led full and interesting lives.

Emma was born on May 12, 1869 in Ohio (according to various U.S. Census records) and passed away on August 3, 1966. According to Syl’s gravestone he was born in 1856 and died in 1947. In the 1860 Census, Sylvester Gamblin was three years old and living in Gap, Montgomery County, Arkansas. His parents were James and Emenella Gamblin.

Emma was born on May 12, 1869 in Ohio (according to various U.S. Census records) and passed away on August 3, 1966. According to Syl’s gravestone he was born in 1856 and died in 1947. In the 1860 Census, Sylvester Gamblin was three years old and living in Gap, Montgomery County, Arkansas. His parents were James and Emenella Gamblin.

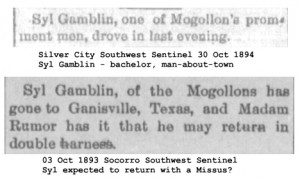

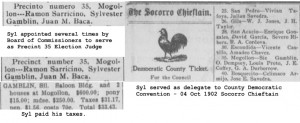

In the 1870 Census, Syl lived in Texas, and in 1880 he lived in Center, Polk County, Arkansas, listed as a boarder with the Davis family. The missing data which could be gleaned from the 1890 U.S. Census records (burned in a fire in 1921) leaves some gaps in Syl’s history and his migration from Arkansas to New Mexico Territory. However, according to various snippets in the Socorro Chieftain and the Silver City Southwest-Sentinel, Syl was in the area in the early 1890s:

I also found a source citation from the 1900 US Census taken in Nome, Alaska, listing Syl Gamblin as a partner in relation to the head of the household and working in the mining industry, along with several other men. That census was taken from May 1 to June 1, 1900. The date of birth, age and place of birth match Syl’s vital data. So, perhaps Syl had decided at some point to try his hand at mining in Alaska.

If true, he apparently didn’t find riches in Alaska and sometime after June 1, 1900 he returned to Mogollon, as evidenced by an IRS Tax Assessment List for taxes due from October 1, 1900 (the date his business commenced) to June 30, 1901 (click to enlarge all graphics).

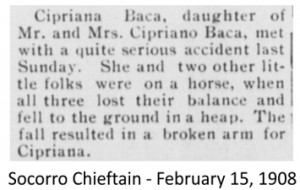

In 1910, according to that year’s census, Syl was still living in Mogollon and single. A mention of Syl in a book about a local law enforcement officer, Cipriano Baca, made a short reference to Syl but did not include dates. In this short blurb (“Cipriana” in the quote below was Cipriano Baca’s daughter) the author mentions Syl:

So the information and graphic above about tax assessments would likely be for the saloon.

Syl was apparently civic-minded. He was appointed as Precinct Election Judge several times, served as a delegate to the County Democratic Convention and he paid his taxes.

Syl Gamblin knew plenty of hardship as well. Like today, the area around Mogollon is prone to both fires and floods:

Syl Gamblin knew plenty of hardship as well. Like today, the area around Mogollon is prone to both fires and floods:

Thus, Syl Gamblin was a prominent citizen of the area as shown by the news articles posted above. NOTE: I searched extensively to locate a picture of Syl without success.

Thus, Syl Gamblin was a prominent citizen of the area as shown by the news articles posted above. NOTE: I searched extensively to locate a picture of Syl without success.

A little more research turned up some interesting information about Emma. Emma (maiden name Williams) married Charles Alfred Shellhorn on January 12 ,1898. I noticed that there were several Shellhorns buried in this cemetery as well. On January 3, 1899 their son Herman was born and died on July 12, 1899. Another child, Harriet, was born one year to the day after Herman’s death, on July 12, 1900. Charles, whose occupation on the 1900 Census was listed as “teamster” died on February 9, 1908. He probably worked in the mines and perhaps died on the job, although I could find no news article about such a disaster around that time.

While searching for a news item about Charles Shellhorn’s death, I came across this news item about little Cipriana Baca, Hattie Shellhorn’s best friend (see book excerpt above):

This accident happened on the same day as Charles Shellhorn, Hattie’s father, died.

In 1910, Emma is listed as a widow on that year’s U.S. Census, living in Mogollon and working as a housekeeper, with one child, Harriet aged 9. Harriet (“Hattie”) died on October 14, 1918 and is buried in the same cemetery. I suspected Hattie was a victim of the 1918 Spanish Flu Pandemic, although according to her death certificate she died of pneumonia. (Hattie Shellhorn Death Certificate) Many people in Mogollon fell ill and died that year, and it is known that in the fall of 1918 the flu strain was much more virulent and deadly (see Albert Samsill Tombstone Article).

So, by 1918, Emma had suffered one loss after another. Her entire family, including her first husband Charles had died. From the book excerpt cited above, it sounds like perhaps Syl had known Emma awhile before they married because he knew Hattie when she was younger. By the 1920 Census, Syl and Emma had married, he being 63 and she 51 and were living in Hansonburg, Socorro County, New Mexico where Syl worked as a stockman or stock raiser. (One record I found suggested Syl and Emma married in 1912, but it was a subscription site, so I couldn’t view the documentation. A search of a New Mexico Marriage database yielded no results either. However, that certainly fits the theory that they married sometime between the 1910 and 1920 Census.) Hansonburg was a mining district.

I found no record of the Gamblins in the 1930 Census, but in the 1940 Census Syl is 82 years old and his occupation is listed as “miner” and living in Mogollon, Catron County, New Mexico. Hmmm…perhaps Syl had been part of the Nome gold strike of 1900 after all and now he was trying his hand again at mining? Come to think of it, there was gold fever in Polk County, Arkansas in the 1880s and Syl lived in Polk County according to the 1880 Census.

Digitized newspapers at the Library of Congress are only available through 1922, and the 1940 Census is the last one available at this time. So the only remaining information I could find about the Gamblins is on their tombstones — Syl died in 1947 and Emma in 1966.

Perhaps Syl Gamblin was a restless soul, wandering near and far, in search of riches and success – or dare I say a “gamblin’ man”. Maybe when he found Emma he found real happiness and contentment at last. Doesn’t that sound like material for a historical fiction/romance book?

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Military History Monday – The Utah War a.k.a. Buchanan’s Blunder

Early Mormon History

During the early 19th century, a revival movement called The Second Great Awakening was sweeping the nation. One particular area in western New York became known as the “Burned Over District”. The area had been so heavily evangelized and saturated with revival that no fuel (unconverted souls) was left to burn (in other words, convert). Many religious and socialist experiments (utopian) sprung from that area – the Shakers, Oneida Society, Millerites (later Seventh Day Adventist) and Latter Day Saints (Mormons). Joseph Smith, the founder of Mormonism, lived in the Burned Over District and was influenced as were many others by the revival.

In 1831, Mormons began to move west into Ohio and Missouri, and in 1840 a new colony was established in Nauvoo, Illinois. For many years the Mormons had faced opposition to their religion, even engaging in armed conflicts. When Joseph Smith moved to Nauvoo he again experienced anti-Mormon sentiment. In 1844 he was arrested, and while in jail a vigilante mob killed him on June 27, 1844.

Mormon Westward Migration

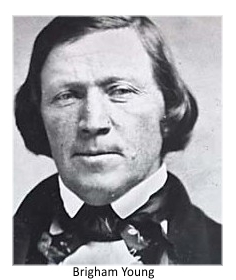

Eventually, leadership of the church passed to Brigham Young, and he led a group west to territory that was at the time still part of Mexico. On July 24, 1847 Young and his group arrived in the Salt Lake Valley with the desire to live out their faith in isolation. Meanwhile, ownership of territory in the West was shifting following the Mexican-American War. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo brought an end to the war in 1848. Now the territory where the Mormons had settled changed hands to the United States.

Eventually, leadership of the church passed to Brigham Young, and he led a group west to territory that was at the time still part of Mexico. On July 24, 1847 Young and his group arrived in the Salt Lake Valley with the desire to live out their faith in isolation. Meanwhile, ownership of territory in the West was shifting following the Mexican-American War. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo brought an end to the war in 1848. Now the territory where the Mormons had settled changed hands to the United States.

In 1849, the Mormons proposed entrance into the Union by joining as the State of Deseret. However, they did not want any outside governing influences (“carpetbaggers”), but rather to be led by those of like faith. Only by governance through their church did they feel they could truly have religious freedom. Congress created the Utah Territory as part of the Compromise of 1850, and President Millard Fillmore appointed Brigham Young as its first territorial governor.

Polygamy was still a major tenet of the Mormon faith and even in their isolation in Utah Territory, the group still remained controversial. The practice of multiple marriages in the rest of the country was considered immoral. Included in the planks of the Republican platform in 1856 was a promise “to prohibit in the territories those twin relics of barbarism: polygamy and slavery.”

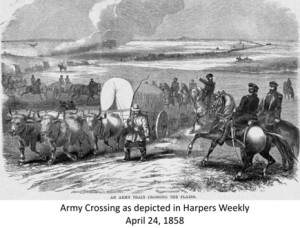

When President James Buchanan came into office in 1857, one of his first initiatives was to address the Mormon issue. By that summer, Buchanan had appointed Alfred Cumming as the new territorial governor to replace Brigham Young and sent out an expedition led by Colonel Albert Sidney Johnston. Once Young became aware that the army was approaching he ordered territory residents to prepare to evacuate. The plans included the burning of homes and stockpiling of food, and LDS missionaries were recalled to return to the territory.

In August of 1857 Utah’s militia, Nauvoo Legion, was reassembled by Young and part of their assignment was to harass the U.S. Army. Before the main U.S. Army contingent was sent out, Captain Stewart Van Vliet had been dispatched with a small group of men to pave the way for the new appointees to be introduced as leaders in the territory.

Van Vliet moved cautiously into the territory expecting little or no resistance (he had previous dealings with Mormons in Iowa). However, Young made it clear that he would not allow the new governor and federal officers to enter the territory. In response to the turmoil and confusion, Young had declared martial law in early August, but the proclamation hadn’t been widely circulated. Upon Van Vliet’s exit from Salt Lake City in mid-September, Young again issued the proclamation – now residents were more aware of the situation and the impending “invasion” by the U.S. Army.

In late September, the Utah militia began to have contact with the U.S. troops and employed delaying tactics and harassment such as burning grass along the Army’s trail or causing the Army’s cattle to stampede. In early October, Fort Bridger was burned down to prevent the Army from encamping there, and soon after that the militia and Army troops were involved in a skirmish in which no one was killed. By late October and into November, weather became a factor with the onset of heavy snowstorms. The Nauvoo Legion had also fortified Echo Canyon which led down to the Salt Lake Valley.

On November 21 the new territorial governor, Alfred Cumming, while on his way to Utah issued a proclamation declaring the residents of the territory to be in rebellion. Soon after a grand jury convened at Camp Scott where Brigham Young and sixty other men were indicted for treason. Meanwhile, there was little that could be accomplished now that winter weather had set in.

On November 21 the new territorial governor, Alfred Cumming, while on his way to Utah issued a proclamation declaring the residents of the territory to be in rebellion. Soon after a grand jury convened at Camp Scott where Brigham Young and sixty other men were indicted for treason. Meanwhile, there was little that could be accomplished now that winter weather had set in.

Back in August Young had contacted a perceived ally, Thomas Kane, who had previously been sympathetic to the Mormon’s plight in dealing with their ongoing controversies before they had headed west. Kane contacted President Buchanan and volunteered to serve as a mediator to resolve the conflict, but the President was concerned that if somehow the Mormons prevailed and destroyed his army, he would pay a heavy political price. Buchanan eventually agreed to allow Kane to attempt mediation so Kane made his way to Utah traveling first to Panama and then up to San Francisco (eventually landing in San Pedro, California because of heavy snow blocking Sierra passes). He was taken across through San Bernardino and Las Vegas and on to Salt Lake City.

Kane was successful in convincing Brigham Young to agree to the installment of Alfred Cumming as the new territorial governor. Kane traveled to Colonel Johnston’s winter encampment to escort Cumming into Salt Lake City in early March of 1858, and by mid-April Cumming had been installed as the new governor. However, tensions continued as there was still the possibility that the U.S. Army would enter Utah. Northern Utah settlers had already begun migrating south in March, boarding up their homes and, if necessary, burn their homes. Yet, even with Cumming’s successful installation, the migration continued.

In their book, The Story of the Latter-Day Saints, LDS historians James B. Allen and Glen M. Leonard noted the following:

It was an extraordinary operation. As the Saints moved south they cached all the stone cut for the Salt Lake Temple and covered the foundations to make it resemble a plowed field. They boxed and carried with them twenty thousand bushels of tithing grain, as well as machinery, equipment, and all the Church records and books. The sight of thirty thousand people moving south was awesome, and the amazed Governor Cumming did all he could to persuade them to return to their homes. Brigham Young replied that if the troops were withdrawn from the territory, the people would stop moving…. (p. 308)

Meanwhile, President Buchanan had come under increasing pressure from some members of Congress who did not want to start a war with the Mormons. Conversely, there were others who supported the efforts and even wanted to increase the size of the Army to deal with the situation. In April, the President sent a Peace Commission to negotiate a settlement, offering a pardon to all Mormons who had any involvement in the conflict with the U.S. government (or preventing the U.S. Army from entering the territory). The commissioners emphasized that the U.S. government did not want to interfere with the Mormons’ right to practice their religion.

Brigham Young eventually agreed to the terms of the proclamation but did not admit that Utah had ever been in direct rebellion of the U.S. government. Near the end of June, the U.S. Army troops made their way into Utah without any resistance. Soon after that, northern Utah settlers began to return to their homes and the army settled into a valley southwest of Salt Lake City. Eventually the troops moved out in 1861 as the Civil War began.

Buchanan’s Blunder

The conflict has been referred to as “Buchanan’s Blunder” in part because (1) Governor Young was not properly notified of his replacement, (2) troops were perhaps dispatched before knowing just how serious (or not) the Utah situation was, (3) supplies were inadequate and (4) the expedition was sent out too late and thus forced to encamp and wait out the winter of 1857-1858.

Aftermath and Consequences

The Mormons themselves lost out because of those who had their lives and livelihoods disrupted, and with the troop occupation the situation still remained tense – many of those troops reportedly reviled the Mormons. Another consequence of the Utah War was the creation of the Pony Express. The Utah militia, in their attempts to harass and keep out unwanted outsider intervention, had burned over fifty mail wagons. That business (Russell, Majors and Waddell) was never reimbursed by the federal government and in 1860 the Pony Express was created so they could obtain a government mail contract and avoid financial ruin.

The Utah War ultimately resulted in the decline of Mormon isolation. By 1869 the Transcontinental Railroad had been completed and with that came an influx of “Gentiles”. Polygamy still remained an issue with the federal government, but finally in 1896 Utah was granted statehood.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Feudin’ and Fightin’ Friday: The Lawless Horrell Brothers (From Lampasas, TX to Lincoln, NM and Back)

Horrells and Higgins – Early Lampasas County Settlers

John Holcomb Higgins and his wife Hester migrated to Lampasas County, Texas from Georgia with their young family. Their son, John Pinkney Calhoun Higgins was their first male child, born on March 28, 1851. The Higgins family was among the first settlers in the county. One source indicated that the Higgins family had moved to Texas in 1848, but I believe that is incorrect as John Pinkney was born in Georgia as noted in subsequent censuses – so not sure the exact date they arrived in Lampasas County.

In 1857 a family named Horrell migrated to the county from Arkansas. According to the 1850 Census, the Horrell family lived in Caddo, Montgomery County, Arkansas and father James (Samuel) was listed as being 30 years of age. Their children (all males) ranged in age from 11 to infant. By the 1860 Census the Horrells had moved to Lampasas County. Since 1850 two more sons and a daughter had been born.

According to at least one source, for several years the families lived peacefully as neighbors. Sometime in the 1870s, however, something changed. One event that surely devastated the Horrell family was the death of Samuel Horrell. I found the following story on Ancestry.com:

Traveling east from Las Cruces, New Mexico, the Horrell party was waylaid by Mescalero Apache Indians at the San Augustine Pass, where Samuel Horrell was killed (14 Jan 1869). It was reported that John’s wife Sarah and Thomas Horrell fought the Indians off with a six-shooter and a rifle. After fighting off the Indians the Horrell party continued on East to take refuge at the Shedd Ranch. By March of 1869, Samuel Horrell’s widow, Elizabeth, had returned to Lampasas, Texas. Elizabeth moved into a house in town near what is now known as the Cloud Warehouse.

Traveling east from Las Cruces, New Mexico, the Horrell party was waylaid by Mescalero Apache Indians at the San Augustine Pass, where Samuel Horrell was killed (14 Jan 1869). It was reported that John’s wife Sarah and Thomas Horrell fought the Indians off with a six-shooter and a rifle. After fighting off the Indians the Horrell party continued on East to take refuge at the Shedd Ranch. By March of 1869, Samuel Horrell’s widow, Elizabeth, had returned to Lampasas, Texas. Elizabeth moved into a house in town near what is now known as the Cloud Warehouse.

According to the Texas Muster Rolls, four of the Horrell brothers had enlisted in a local militia commanded by George E. Haynie. The brothers Benjamin, Mart and Merritt are listed as joining on September 11, 1872 and service was 17 days, but the final muster date wasn’t until March 10, 1874. Tom Horrell’s signup date was September 12, 1872 and he served 16 days with the same final muster date as his brothers.

According to one internet source (Legends of America), the brothers’ first run-in with the law occurred in January 1873, but the young men were already known to have been troublemakers. At this period of time, the county was a wild and woolly place to live. The Sheriff of the county, Shadick T. Denson, attempted an arrest of two friends of the brothers, but the Horrells intervened and the Sheriff was shot and later died.

The county judge appealed to Governor Edmund J. Davis to intervene, and on February 10, 1873 the Governor issued a proclamation which banned small arms in Lampasas. In March, seven members of the Texas State Police came to enforce the Governor’s proclamation. On the 19th of March, Bill Bowen, brother-in-law of the Horrell brothers, was arrested for possession of a gun. According to Legends of America, the law officers entered a saloon with Bowen and a gunfight ensued. Four officers lay dead.

Horrell War – Lincoln County, New Mexico

Now the Horrell brothers were wanted for murder. Law enforcement finally arrested Mart Horrell and three others and took them to the jail in Georgetown, Texas, but on May 2 the men escaped from jail after Mart’s brothers and several other cowboys descended on the town and freed them.

The brothers remained around the area for awhile and then headed to Lincoln County, New Mexico, camping on the Rio Ruidoso near present day Hondo. On December 1, 1873, Ben Horrell and two others rode into Lincoln and begin to carouse and cause trouble. When the local Constable Juan Martinez demanded their guns be turned over they complied, but soon found replacements and continued on through the town making trouble.

According to Legends of America, one of the men with Ben Horrell (Dave Warner) had a long-standing grudge against Martinez. When confronted again by the Constable, Warner shot and killed Martinez. The other lawmen with Martinez shot and killed Warner on the spot, but Ben and the other man, Jack Gylam (himself an ex-Lincoln County Sheriff), fled. The lawmen pursued the two and when they caught up with them, killed them (Ben 9 times and Gylam 14 times).

Retaliation by the remaining Horrell brothers came swiftly when they killed two Hispanics who were prominent citizens of the area. On December 20, the brothers returned to Lincoln to continue their vendetta by killing four men and wounding a woman. Efforts to arrest the Horrells were fruitless and eventually in early 1874 the brothers and their friends made their way back to Texas. Along the way, they still had some sort of revenge against Hispanics on their agenda. Deputy Sheriff Joseph Haskins of Pichaco, New Mexico was killed (sources suggest he was killed because he was married to an Hispanic woman). Approximately fifteen miles west of Roswell, New Mexico the gang killed five other Hispanics.

Horrells vs. Higgins

The Horrells finally arrived back in Texas and in 1876 were tried for the death of State Police Officer Captain Thomas Williams – they were acquitted. Tensions with the Higgins family, specifically John Pinkney “Pink” Higgins, came to a head. In May of 1876, Higgins filed a complaint accusing Merritt Horrell of stealing his cattle. Merritt was tried, but again a Horrell brother was acquitted. Higgins vowed to settle the matter with a gun.

On January 22, 1877, Pink carried out his threat and killed Merritt Horrell in a Lampasas saloon. Of course, the other Horrell brothers vowed revenge on Higgins and his brother-in-law, Bob Mitchell and friend Bill Wren. On March 26, Tom and Mart Horrell were ambushed by the Higgins group but were only wounded. A warrant was issued for Higgins and friends’ arrest. They each posted a $10,000 bond and were released. However, on June 4, the courthouse was burglarized and their records were stolen (coincidence? – I think not!).

Shortly after the break-in, Higgins and friends rode into Lampasas and a gunfight ensued with the Horrells and their friends. Bob Mitchell’s brother, Frank, lay dead along with two others who were friends of the Horrells. Subsequently, the Texas Rangers were dispatched to negotiate a cease fire. By early August, both parties had agreed to stop their feuding. The next year, however, Tom and Mart Horrell, were suspects in a robbery/murder case of a storekeeper in Bosque County. They were jailed and later a mob stormed the jail and shot both of them to death.

The one Horrell brother, Samuel, said to be the oldest and most peaceable, eventually moved to Oregon and died there in 1936. Pink Higgins moved his family to the Spur, Texas area and died there of a heart attack in 1914.

The one Horrell brother, Samuel, said to be the oldest and most peaceable, eventually moved to Oregon and died there in 1936. Pink Higgins moved his family to the Spur, Texas area and died there of a heart attack in 1914.

History Bonus: Here’s a PDF File of Pink Higgins’ story found at Find-A-Grave (Pink Higgins ). He certainly lived an interesting life if this is all true – definitely worth a read.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Ghost Town Wednesday – Daisy Colony: Oklahoma’s “Amazon Women”

I had seen this “ghost town” mentioned in my recent research for ghost town stories, so I will loosely place it under that category because it’s pretty interesting. Over the years, some people have thought this might be the same group of women who formed Bathsheba (which lasted only a short time – see this blog article), but it does appear to be a different group of women.

I found one reference, actually an article written anonymously. This person constructed the story of “Daisy Colony” with newspaper articles written about a group of “venturesome” women. The group was led by a woman referred to as Annetta (or Annette) Daisy.

I found one reference, actually an article written anonymously. This person constructed the story of “Daisy Colony” with newspaper articles written about a group of “venturesome” women. The group was led by a woman referred to as Annetta (or Annette) Daisy.

This humorous and informative article has been re-written and enhanced, and published (complete with footnotes and sources) in the May 2018 issue of Digging History Magazine. Should you prefer to purchase the article only, contact me for more information.

This humorous and informative article has been re-written and enhanced, and published (complete with footnotes and sources) in the May 2018 issue of Digging History Magazine. Should you prefer to purchase the article only, contact me for more information.

I invite you to check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Tombstone Tuesday: A.E. Sipe (Glenwood Cemetery – Catron County, New Mexico)

At the suggestion of my cousin, Terrie Henderson, I decided to check out some cemeteries in Catron County, New Mexico. Several of the sites I perused had extensive details of both the lives and deaths on the individual Find-A-Grave web page. For instance, the Boot Hill Cemetery has but 8 interments. Initially I thought this might be a good one to research but since a lot of information has already been documented, I wanted to find something more challenging.

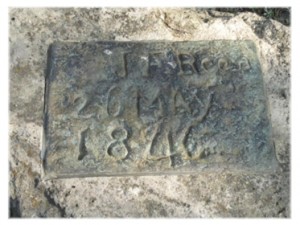

I continued looking through the Catron County cemeteries and came upon the Glenwood Cemetery. I saw a picture of a sign with the name of the cemetery:

The name of the founder, A.E. Sipe, caught my eye and the fact that the precise founding date was noted. Would I find A.E. Sipe himself buried in this cemetery?

This article has been “snipped”. The article was updated, with new research and sources, for the September-October 2020 issue of Digging History Magazine. It is included in the article entitled “The Dash: A.E. Sipe (1855-1909)” with much more research about Adolphus Elijah Sipe and his family, plus what really happened to him. How and where did he die? This issue is Part II of a short series of articles dedicated to New Mexico history and how to find the best genealogical records. The September-October 2020 issue is available here: https://digging-history.com/store/?model_number=sepoct-20

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Military History Monday – Obscure U.S. Civil Wars – The Walton War

In this border war which occurred in the first decade of the 1800s, ambiguities in border delineation were again the center of controversy. The strip of land, approximately twelve miles wide, was called the “Orphan Strip”. That strip of land bordered the three states of North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia.

In this border war which occurred in the first decade of the 1800s, ambiguities in border delineation were again the center of controversy. The strip of land, approximately twelve miles wide, was called the “Orphan Strip”. That strip of land bordered the three states of North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia.

Originally, after the Revolutionary War, there was a dispute between North and South Carolina. States who previously had claims to land west of the Appalachian Mountains to the Mississippi River were asked to cede those lands back to the federal government. North Carolina ceded their western land (eventually becoming Tennessee) and South Carolina only needed to cede a small strip of land in order to comply with the federal government’s wishes. Georgia agreed to cede the land that would later become Alabama and Mississippi, and in return the federal government agreed that Georgia would receive the small strip of land that South Carolina had ceded. That occurred in 1802, so now Georgia and North Carolina shared a border.

Originally, after the Revolutionary War, there was a dispute between North and South Carolina. States who previously had claims to land west of the Appalachian Mountains to the Mississippi River were asked to cede those lands back to the federal government. North Carolina ceded their western land (eventually becoming Tennessee) and South Carolina only needed to cede a small strip of land in order to comply with the federal government’s wishes. Georgia agreed to cede the land that would later become Alabama and Mississippi, and in return the federal government agreed that Georgia would receive the small strip of land that South Carolina had ceded. That occurred in 1802, so now Georgia and North Carolina shared a border.

The problem likely arose because the land was never properly surveyed (duh!). At the eastern edge of the land strip was an area that North Carolina believed to be its Buncombe County. In 1785 settlers had begun to cross the Blue Ridge Mountains and settled that area. By 1802 there were about 800 residents and many of those settlers had received their land grants from South Carolina (remember that officially South Carolina had ceded that strip back to the government who in turn had ceded it to Georgia), while others had received grants from North Carolina.

Of course, agitation and confusion ensued because these settlers didn’t want to lose their land. In 1803, Georgia decided to intervene by proceeding to create Walton County out of the disputed territory, named for one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence, George Walton. Farmers who held South Carolina land grants supported the new county government but rejected any jurisdiction asserted by Buncombe County (North Carolina). Conversely, those who held North Carolina land grants supported Buncombe County but not Walton County (Georgia).

By December 1804 the dispute came to a head when Walton County officials decided to settle the dispute once and for all, seeking to evict any remaining Buncombe County supporters. John Havener, a Buncombe County constable, was struck in the head with the butt of a musket and died. Buncombe County immediately called for militia to be dispatched to the area. On the 19th of December, Major James Brittain with a group of seventy-two militia marched into the area and was joined by twenty-four other North Carolinians who lived in the area.

Ten suspected Walton County officials were captured and sent to Morganton, North Carolina to stand trial for the murder of Havener. The dispute continued until in 1807 a commission was formed in order to settle the matter. After surveying the area properly, the true boundary was found to be a few miles south of its original presumed position. Georgia commissioners finally admitted that all of Walton County rightly belonged to North Carolina.

In the end, all was forgiven (with the exception of the ten men accused of murder – however, those men escaped and were never seen again). North Carolina eventually recognized the South Carolina land grants.

I ran across one person’s story about her genealogical research in which this dispute actually caused some confusion (this might solve someone else’s confusion as well):

For many years I was puzzled by the fact that so many of my ancestors seemed to move around so much, back and forth between North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia. Moving would have caused tremendous work, time and hardship back then due to the mountainous, inaccessible terrain. There was also so much conflicting information on various census: on one census a person would state that her mother was born in Georgia and on the next census state North Carolina or South Carolina. Then I remembered the Walton War and what confusion it must have caused the inhabitants of this area. For many several years they were claimed as citizens of three different states. I wondered if perhaps they might never have moved at all but were unsure of which state they were being claimed by at the moment. These people could have stayed where they were and yet have technically lived in North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia during this time period. This was verified by finding some of my ancestors listed on the census of Walton County, Georgia when I know for sure that they were living on land located near the Jackson-Transylvania County, North Carolina border. So if you are working on your genealogy and have relatives in this area, remember the Walton War! – Shawna Hall (no relation that I know of).

Today, the originally disputed land is now part of the North Carolina county of Transylvania.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Ghost Town Wednesday – Alcove Springs, Kansas

I found the subject of today’s article on another blog which listed the ten best “ghost” towns to visit in Kansas. The author’s caveat was that it never became a town, but it is quite historical (and worth a trip to see) – known as the most historic place in Kansas on the Oregon Trail.

The name was given to the springs by a member of the Donner-Reed Party in 1846, although it was a known place along the trail which fur trappers traversed in the late 1820s and 1830s. The first mention of the springs was made by travelers of the “Great Migration” in 1843.

“Alcove” was the name given the springs for its appearance, a shelving of rocks over which water flowed.

The springs became a popular place to stop because quite often when the emigrants reached this point in their journey the Blue River was at flood stage – Alcove Springs became a place to wait until the river level went down so they could continue. According to the Oregon-California Trails Associate web site, there are several carvings on the ledge and rocks surrounding the area, as well as wagon ruts. It is undoubtedly true that some people who stopped to rest at this location and made their carvings, never made it to their final destination. Mormons heading west probably passed through that area as well – it is said some may have been buried there after dying of cholera. The Oregon Trail has been referred to as “the world’s longest graveyard”.

There are probably more than a few emigrants buried in and around the area. One of the most notable emigrants was the subject of yesterday’s Tombstone Tuesday, Mrs. Sarah Keyes. One of the carvings was made by James Reed, Mrs. Keyes son-in-law. The picture below was taken by Don Weinell (as well as the one above); however, he wasn’t sure if this was the original carving or had been moved to another location:

Alcove Springs had an unusual “post office” system. In 1849, William Johnson observed the following:

“We found here also one of the kind of postoffices peculiar to the plains — a stick driven into the ground, in the upper end of which, in a notch, communications are placed, intended for parties following. A letter in this postoffice was found addressed to Captain Pyle. It was from Captain Paul, giving information that at this place his driver, John Fuller, had accidentally shot and killed himself whilst removing a gun from the wagon.”

(I’m not entirely sure, but William Johnson may have been one of the Donner Party rescuers in the winter of 1846-1847.)

(I’m not entirely sure, but William Johnson may have been one of the Donner Party rescuers in the winter of 1846-1847.)

From the pictures I’ve seen, this “ghostly” place in Kansas sounds like a beautiful place to visit, officially listed as one of the “8 Wonders of Kansas Geography”. The site is also listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The springs are located approximately 2 miles north of Blue Rapids, Kansas; turn right at the sign and head west for 6 miles on a gravel road.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Tombstone Tuesday – The Tale of Two Sarahs

Today I’m starting a “mini-series” for this week of all things spooky and haunting (if you’re into that kind of thing). The articles today through Friday will be about different events and places surrounding the ill-fated Donner Party. Today’s article is about the tale of two Sarahs – one who died not long after the trip’s beginning and the other who actually made it to California after being caught in Nevada in the snow storm and subsequent events that doomed so many.

Sarah (Handley) Keyes

According to the Find-A-Grave web site, Sarah Handley Keyes was born in 1776 in Monroe County, Virginia (no specific date of birth given, however, and I wasn’t able to locate more detailed information). Her parents were Major John Handley and Mary (Harrison) Handley. The grave stones of the Major, his wife and Sarah all have commemorations indicating John Handley was an American Revolutionary patriot (DAR plaques). I found conflicting information indicating that perhaps this John Handley did not serve in the Revolutionary War, but had been a Major of the Virginia Militia during the Whiskey Rebellion of 1793.

Sarah Handley married Humphrey Keyes on April 21, 1803 in Monroe County, Virginia. She and Humphrey had six children. I found one reference that seemed to indicate that Humphrey might have been a lawyer or judge. As noted in both the 1820 and 1830 United States Censuses, the Keyes family lived in Monroe County (Peterstown), Virginia. The Keyes family, according to “History of Early Settlers of Sangamon County, Illinois” arrived in Springfield, Illinois on November 10, 1830. The book also notes that Sarah was Humphrey’s second wife. With his first wife (Strider or Streider last name), he had five children before she died. Humphrey died in 1833.

Sarah Handley married Humphrey Keyes on April 21, 1803 in Monroe County, Virginia. She and Humphrey had six children. I found one reference that seemed to indicate that Humphrey might have been a lawyer or judge. As noted in both the 1820 and 1830 United States Censuses, the Keyes family lived in Monroe County (Peterstown), Virginia. The Keyes family, according to “History of Early Settlers of Sangamon County, Illinois” arrived in Springfield, Illinois on November 10, 1830. The book also notes that Sarah was Humphrey’s second wife. With his first wife (Strider or Streider last name), he had five children before she died. Humphrey died in 1833.

Sarah was now widowed at age 57 and her daughter, Margret, was widowed that same year. In 1835 Margret married James Frazier Reed. According to the 1840 Federal Census, a female between the ages of 50 and 60 resided in the Reed household, so it’s safe to assume that would be Sarah Keyes. James Reed would be one of the leaders, along with George and Jacob Donner, of a group heading west in 1846. Reed was a wealthy businessman who had served with Abraham Lincoln in the Black Hawk War of 1832 (Lincoln with the Fourth Regiment and Reed with an Independent Company).

In 1845 Reed, along with the Donners, planned their trek to California and started from the Springfield, Illinois area on April 14, 1846. By this time, Reed’s mother-in-law, Sarah Keyes, was in poor health (consumption) but was determined to make the journey with her daughter’s family because she had hopes of seeing one of her sons, Robert Cadden Keyes, who had headed west a few years prior.

According to Daniel Brown, author of “The Indifferent Stars Above”, Reed deemed himself to be the natural leader of the group – also that those who traveled with him thought him to be quite full of himself. According to Brown, one of the reasons for the Reeds to relocate to California was to cure his wife’s migraines or “sick headaches”. He goes on to say that Margret was so frail that at her wedding she had lain in bed during the ceremony while James held her hand.

The Reeds were quite well-to-do and set off on their journey in a wagon described by Reed’s stepdaughter, Virginia Reed Murphy, in 1891:

Our wagons, or the “Reed wagons,” as they were called, were all made to order and I can say without fear of contradiction that nothing like our family wagon ever started across the plains. It was what might be called a two-story wagon or “Pioneer palace car,” attached to a regular immigrant train. My mother, though a young woman, was not strong and had been in delicate health for many years, yet when sorrows and dangers came upon her she was the bravest of the brave. Grandma Keyes, who was seventy-five years of age, was an invalid, confined to her bed.

Her sons in Springfield, Gersham and James W. Keyes, tried to dissuade her from the long and fatiguing journey, but in vain; she would not be parted from my mother, who was her only daughter. So the car in which she was to ride was planned to give comfort.

The entrance was on the side, like that of an old-fashioned stage coach, and one stepped into a small room, as it were, in the centre of the wagon. At the right and left were spring seats with comfortable high backs, where one could sit and ride with as much ease as on the seats of a Concord coach. In this little room was placed a tiny sheet-iron stove, whose pipe, running through the top of the wagon, was prevented by a circle of tin from setting fire to the canvas cover. A board about a foot wide extended over the wheels on either side the full length of the wagon, thus forming the foundation for a large and roomy second story in which were placed our beds.

Under the spring seats were compartments in which were stored many articles useful for the journey, such as a well filled work basket and a full assortment of medicines, with lint and bandages for dressing wounds. Our clothing was packed–not in Saratoga trunks–but in strong canvas bags plainly marked. Some of mama’s young friends added a looking-glass, hung directly opposite the door, in order, as they said, that my mother might not forget to keep her good looks, and strange to say, when we had to leave this wagon, standing like a monument on the Salt Lake desert, the glass was still unbroken. I have often thought how pleased the Indians must have been when they found this mirror which gave them back the picture of their own dusky faces.

We had two wagons loaded with provisions. Everything in that line was bought that could be thought of. My father started with supplies enough to last us through the first winter in California, had we made the journey in the usual time of six months. Knowing that books were always scarce in a new country, we also took a good library of standard works. We even took a cooking stove which never had had a fire in it, and was destined never to have, as we cached it in the desert. Certainly no family ever started across the plains with more provisions or a better outfit for the journey; and yet we reached California almost destitute and nearly out of clothing.

If you’d like to read the entire account you can do so by clicking here.

The Reeds traveled on through Missouri, reaching the western side (St. Joseph and Independence) which was the commonly known jumping off point for those traveling west on the Oregon and California Trails. For travelers, it was a chance to stock up on supplies or see a doctor before heading out beyond the borders of the United States. Here are prices for various medical procedures:

50 cents – tooth extraction

$1 – seek medical advice or receive an enema

$5 – a toe or finger amputated; $10 for an arm and $20 for a leg

$5 – per baby delivered

After crossing the Missouri River, those headed west would travel into what is now known as Kansas. The Reeds and the Donners and another party (Russell Party) stopped at a bucolic site which was named by one member of the party as “Alcove Springs” and carved into one of the rocks. The Big Blue River had risen after thunderstorms and they were waiting for the level to drop so they could cross and continue their journey.

On May 29, 1846, Sarah Handley Keyes, age seventy years passed away. She had not been able to fulfill her wish of seeing her son Robert one more time. Her granddaughter Virginia wrote to her cousin in Illinois about the passing of her grandmother:

We buried her verry decent. We made a nete coffin and buried her under a tree we had a head stone and had her name cut on it and the date and yere verry nice, and at the head of the grave was a tree we cut some letters on it the young men soded it all ofer and put flores on it. We miss her very much every time we come into the Wagon we look at the bed for her.

After the river level dropped, the travelers were able to use a log ferry to cross and continue on their journey. The Donners and Reeds reached Fort Laramie on June 27, now known as the “Boggs Company” – named after it’s leader Lilburn W. Boggs, a former Missouri governor. The group celebrated the Fourth of July before continuing on their journey to Fort Bridger to meet up with Lansford Hastings who was to guide them to California. However, upon arrival at Fort Bridger they learned that Hastings had already left a week prior so they had to head out without his leadership (encouraged by Jim Bridger) – they hoped to make it to Captain Sutter’s fort in California territory in seven weeks. Just a few days out they found a note left by Hastings telling them that the road ahead was treacherous and impassable, so James Reed and two other men set out to find Hastings and get the new instructions. On August 11, 1846, just after receiving the new instructions, the group was joined by the family of Franklin Graves.

Franklin Graves had set out with his family from Steuben Township on the Illinois River on April 12, 1846. His group included: his wife, Elizabeth and their children: Sarah (and her new husband, Jay Fosdick), Mary, William, Eleanor, Lovina, Nancy, Jonathan, Franklin, Jr., youngest daughter Elizabeth and a teamster named John Snyder.

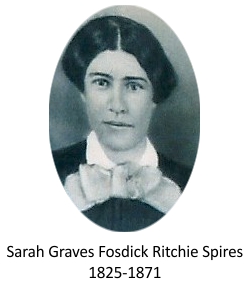

Sarah Graves Fosdick (Ritchie Spires)

Sarah Graves was born in Indiana on January 25, 1825 to Franklin and Elizabeth Graves. Sarah was their oldest child, following the death in infancy of their first child. According to Daniel Brown, the family moved to Illinois in 1831 and expanded to a total of nine children. Many people in the 1830s and 1840s began to grow restless to pick up and move to other lands in search of more prosperity and opportunities. Fueling that restlessness was a book published by Lansford Warren Hastings in 1845, called “The Emigrant’s Guide to Oregon and California”. The drier and warmer climate, along with the promise of “unexhausted and inexhaustible resources” was enticing to many. Franklin became restless too and planned a move west to seek a better life for his family. On April 2, 1846 Franklin sold his land. He had originally purchased the 500 acres in 1836 and 1838, according to Illinois Land Purchase Records, for $1.25 per acre. That day he sold the land for $3.00 an acre, a tidy sum of $1,500. Upon returning to their home, he made preparations to secure the money by secreting it away in wooden cleats (cabinets) and then nailing them to the bottoms of his three wagons. He did it in such a way as to make it look like these pieces were in place to support the wagon.

His eldest daughter, Sarah, was in love with a young man named Jay Fosdick. Sarah was torn between her love for Jay and the love and nearness of her family. On the same day that her father had gone to the courthouse to sell his land, she and Jay stood before a Justice of the Peace and were married. They would leave Illinois together headed to the unknowns of California (and everything in between) as newlyweds.

The Graves family and teamster John Snyder set out from Illinois on April 12, 1846. They followed much the same route and experienced much the same things that others who had traveled the route before them. On August 11, 1846 they met up with the larger Donner/Reed (Boggs) party and began traveling with them. There were even more challenges ahead with tempers flaring and exhaustion setting in, even death. Just after the first of November, the group reached Truckee Lake and spent the night – overnight it began to snow. The Donner group had earlier split but eventually they met up again and discovered they were now trapped and unable to go any further.

The winter was brutal and, as we now know, turned decent Christian people into cannibals to survive. Jay and Sarah joined a group in mid-December which left on snow shoes to try and cross over the mountains. The group became known as “Forlorn Hope”. On Christmas Eve, Sarah’s father, Franklin, died in her and sister Mary Ann’s arms. On January 7, 1847 Jay died, but Sarah and Mary Ann continued on.

Late on the night of January 18, Sarah and Mary Ann approached a cabin situated by the Bear River. The survivors who made it through were described by a young woman from England:

I shall never forget the looks of those people, for the most part of them was crazy & their eyes danced & sparkled in their heads like stars.

Sarah and Mary Ann were nurtured back to health. Their siblings William, Eleanor, Lovina, Nancy and Elizabeth were all rescued. Franklin, Jr. had been rescued and then abandoned and died on or about March 11, 1947. Their mother Elizabeth, like Franklin, Jr. was rescued and abandoned and died probably about the same time as her son. Little Elizabeth died soon after arriving at Sutter’s Fort.

The children of Franklin and Elizabeth Graves who survived went on to marry and have large families of their own. Sarah married William Dill Ritchie (one of the rescuers) in 1848. They had three sons: George, Gus and Alonzo (one died in infancy). William was hanged as a horse thief near Sonoma on May 30, 1854, even though he claimed innocence. In 1856, Sarah remarried once again, this time to Samuel Spires, with whom she had four children: Lloyd, William, Eleanor and Alice Barton.

On March 28, 1871, Sarah died suddenly and unexpectedly in Santa Cruz County, California. The following is noted on her Find-A-Grave page:

Find a Grave contributor, J.D. Larimore, has done extensive research on Corralitos Cemetery and the Graves family and has discovered that Sarah Graves Spires was probably buried in the Corralitos Cemetery first, and then removed to the Pioneer Cemetery when Corralitos Cemetery was turned into an orchard. She has also been unable to find a record or a headstone for Sarah, but believes that she is among the more than 100 unidentified graves in Pioneer Cemetery.

Two Sarahs – both determined to make the ill-fated trip west. One was old and frail and didn’t live long enough to see her son one more time. The other, young and full of life, probably had to grow up considerably because of the tragic events that ensued – and then she died much too young.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Obscure U.S. Civil Wars – The Toledo War (1835-1836)

Here is another United States “civil war” or boundary dispute that portended a fierce and future college football rivalry. This one was between Ohio and Michigan.

Ohio became a sovereign state of the United States in 1803. Michigan, still a territory in 1835, would soon petition for statehood. As with last week’s “Honey War” between Iowa and Missouri, this conflict had its basis in another misunderstanding of geographic features – this time the Great Lakes.

In 1787 the Northwest Ordinance had been enacted which established the Northwest Territory. The Ordinance specified that at least three and no more than five states were to eventually be carved out of that territory. This part of the Ordinance was apparently misunderstood:

…if Congress shall hereafter find it expedient, they shall have authority to form one or two States in that part of the said territory which lies north of an east and west line drawn through the southerly bend or extreme of Lake Michigan.

Without going into a lot of detail, it appears that the basis of the two states’ conflict over the border stemmed from either unreliable or outdated maps. The U.S. Congress had relied on the so-called “Mitchell Map” to map out the boundaries of Ohio. In 1802 at the Ohio Constitutional Convention, the delegates may have received reports from trappers that claimed that Lake Michigan extended further south than first thought. Thus, this would be significant to know precisely as the Northwest Ordinance had specifically mentioned the southernmost end of Lake Michigan.

In the minds of the Ohio delegates, that meant that Ohio would have more land accorded it. When Congress created Michigan Territory in 1805, they were using the Northwest Ordinance as a guideline and had actually already advised Ohio before its admission that the correct boundary was yet to be determined.

In the minds of the Ohio delegates, that meant that Ohio would have more land accorded it. When Congress created Michigan Territory in 1805, they were using the Northwest Ordinance as a guideline and had actually already advised Ohio before its admission that the correct boundary was yet to be determined.

The contested border ran along an area that would eventually become the city of Toledo. Residents of that area wanted the dispute resolved so they petitioned Congress in 1812. Congress approved but the actual survey wasn’t done until 1816 (War of 1812 caused the delay) after Indiana joined the Union. As it happened, the U.S. Survey General, Edward Tiffin, was a former Ohio governor. Tiffin’s surveyor, William Harris, determined that the disputed territory was in Ohio.

When the results were made public the governor of Michigan Territory, Lewis Cass, was none too pleased. Cass commissioned his own survey, which was done by John A. Fulton. Fulton’s survey was based on the 1787 Ordinance and he found the Ohio boundaries to be south of the disputed area (mouth of the Maumee River). This disputed region then became known as the “Toledo Strip”.

Ohio refused to cede the land, but that didn’t stop Michigan from quietly occupying that territory, even collecting taxes. The area was, and still is, significant. At that point in history, the railroads weren’t in wide use yet so most of the transport of goods was done via rivers and canals. During the conflict over the Toledo Strip, the Erie Canal was built, completed in 1825. This event opened up all kinds of possibilities for transportation, trade and agriculture, so it’s easy to see why the conflict heated up – it largely became a matter of economics and which state or territory would benefit the most.

By the early 1820s, Michigan had reached the minimum population to begin the process of applying for statehood. In 1833, Michigan wanted to hold a state constitutional convention but their request was rebuffed by the U.S. Congress because the issue of the still-disputed Toledo Strip had not been resolved. Of course, Ohio still claimed that the disputed area was within their legal boundaries.

Acting Michigan Territory Governor, Stevens T. Mason, decided to move forward with the Michigan constitutional convention to be held in May of 1835 – despite the ongoing stalemate (Congress was still opposed). Meanwhile in February of 1835, Ohio passed legislation to set up county governments in the Toledo Strip. To add insult to injury, the county where Toledo was situated was named “Lucas” after the sitting Ohio governor, Robert Lucas.

Michigan’s governor was young (24) and said to be “hot-headed”. Six days after Lucas County, Ohio was formed, he responded by passing a bill called the “Pains and Penalties Act”. The Act made it unlawful for Ohioans to carry out governmental activities in the Toledo Strip; the fine was up to $1,000 and/or a five-year prison sentence. Mason, acting as commander-in-chief of the territory, sent Brigadier General Joseph W. Brown of the U.S. Brigade to head the state militia, instructing him to be ready to act against any trespassers in case the need arose. Mason also received approval for a militia of his own and sent them to the Strip. The Toledo War was on.

On March 31, 1835, Governor Lucas sent his own troops (600) to the area, encamping in an area about ten miles southwest of Toledo. Not long after, Mason arrived with his troops numbering around 1000 men. Meanwhile, President Andrew Jackson was determined to avoid an armed conflict, so he asked his Attorney General, Benjamin Butler, to look into the matter and write an opinion regarding the border dispute.

Politically speaking, Ohio was a powerhouse at the time, having nineteen representatives and two senators in the U.S. Congress. Michigan, still a territory, had only one non-voting delegate. As the case is today, Ohio was considered a swing state, too crucial for the Democratic Party to lose in a presidential election. Jackson, of course a loyal Democrat, sided with Ohio in the dispute. But, his attorney general had a different opinion – in his opinion the disputed land should remain as part of Michigan Territory until Congress resolved the issue.

Jackson’s response was to send two representatives, Richard Rush of Pennsylvania and Benjamin Howard of Maryland, to arbitrate the conflict. Their recommendation was to let the residents of the Strip hold an election to decide on their own which side would govern them. Governor Lucas reluctantly agreed to the proposed compromise and ordered his militia to begin disbandment. The elections were held a few days later but Governor Mason would not back down and continued to prepare for armed conflict.

Governor Lucas sent out surveyors to again mark the original Harris line survey. However, on April 26, 1835 the surveyors were attacked by General Brown’s militia in what was called the Battle of Phillips Corners. Each side disputed whether actual shots were fired, but it did “up-the-ante” considerably. Governor Lucas responded by officially establishing Toledo as the county seat of Lucas County. In the meantime, Michigan’s legislature funded a budget of $315,000 for its militia (after Ohio had approved its own militia funding of $300,000). The legislature also drafted its constitution, even though Congress was still not willing to allow entrance to the Union because of the dispute.

In the month of June and into July minor skirmishes occurred, each side trying to “one-up” the other. On July 15, the one and only wound and bloodshed was incurred in the conflict, the result of a Michigan Sheriff being stabbed with a pen knife. By August, President Jackson intervened and removed Mason from his office as Governor of Michigan Territory, replacing him with John S. Horner. Up until the end of his time in office, Mason still tried unsuccessfully to prevent the county government of Lucas County, Ohio from proceeding.

Horner’s tenure was unpopular and short – he was burned in effigy! During the 1835 Michigan election, the people returned the feisty Mason to office. On June 15, 1836 President Jackson signed a bill admitting Michigan to the Union, provided they cede the disputed strip of land to Ohio. As a consolation, Michigan was offered land in the Upper Peninsula which was perceived as worthless and ultimately rejected.

Michigan was facing increasingly more financial problems due to its excessive funding of the militia – they were near bankruptcy. But, they had heard that the U.S. government was soon to distribute a $400,000 surplus to states. Michigan, still a territory because they had rejected Jackson’s stipulation, would not be eligible. Well, well …. there’s nothing like the promise of a “government bailout”!

On December 14, 1836, delegates in Ann Arbor passed a resolution agreeing to all the terms set forth by Congress. There was some controversy at the time as to whether the convention was even legal, but Congress decided to accept their resolution and move forward with statehood. On January 26, 1837, Michigan was officially the 26th state admitted to the Union (sans the Toledo Strip).

As it turned out, the settlement of the conflict was a win for both sides. Even though Michigan had initially rejected the land in the Upper Peninsula, it was later found to be an area rich in natural resources. The port of Toledo probably benefited as well from the mining boom and subsequent commerce. Today, Michiganders and Ohioans just duke it out on the football field!

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!