Early Mormon History

During the early 19th century, a revival movement called The Second Great Awakening was sweeping the nation. One particular area in western New York became known as the “Burned Over District”. The area had been so heavily evangelized and saturated with revival that no fuel (unconverted souls) was left to burn (in other words, convert). Many religious and socialist experiments (utopian) sprung from that area – the Shakers, Oneida Society, Millerites (later Seventh Day Adventist) and Latter Day Saints (Mormons). Joseph Smith, the founder of Mormonism, lived in the Burned Over District and was influenced as were many others by the revival.

In 1831, Mormons began to move west into Ohio and Missouri, and in 1840 a new colony was established in Nauvoo, Illinois. For many years the Mormons had faced opposition to their religion, even engaging in armed conflicts. When Joseph Smith moved to Nauvoo he again experienced anti-Mormon sentiment. In 1844 he was arrested, and while in jail a vigilante mob killed him on June 27, 1844.

Mormon Westward Migration

Eventually, leadership of the church passed to Brigham Young, and he led a group west to territory that was at the time still part of Mexico. On July 24, 1847 Young and his group arrived in the Salt Lake Valley with the desire to live out their faith in isolation. Meanwhile, ownership of territory in the West was shifting following the Mexican-American War. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo brought an end to the war in 1848. Now the territory where the Mormons had settled changed hands to the United States.

Eventually, leadership of the church passed to Brigham Young, and he led a group west to territory that was at the time still part of Mexico. On July 24, 1847 Young and his group arrived in the Salt Lake Valley with the desire to live out their faith in isolation. Meanwhile, ownership of territory in the West was shifting following the Mexican-American War. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo brought an end to the war in 1848. Now the territory where the Mormons had settled changed hands to the United States.

In 1849, the Mormons proposed entrance into the Union by joining as the State of Deseret. However, they did not want any outside governing influences (“carpetbaggers”), but rather to be led by those of like faith. Only by governance through their church did they feel they could truly have religious freedom. Congress created the Utah Territory as part of the Compromise of 1850, and President Millard Fillmore appointed Brigham Young as its first territorial governor.

Polygamy was still a major tenet of the Mormon faith and even in their isolation in Utah Territory, the group still remained controversial. The practice of multiple marriages in the rest of the country was considered immoral. Included in the planks of the Republican platform in 1856 was a promise “to prohibit in the territories those twin relics of barbarism: polygamy and slavery.”

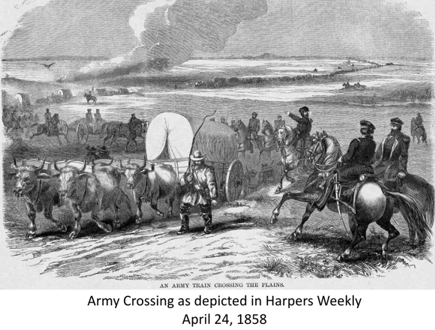

When President James Buchanan came into office in 1857, one of his first initiatives was to address the Mormon issue. By that summer, Buchanan had appointed Alfred Cumming as the new territorial governor to replace Brigham Young and sent out an expedition led by Colonel Albert Sidney Johnston. Once Young became aware that the army was approaching he ordered territory residents to prepare to evacuate. The plans included the burning of homes and stockpiling of food, and LDS missionaries were recalled to return to the territory.

In August of 1857 Utah’s militia, Nauvoo Legion, was reassembled by Young and part of their assignment was to harass the U.S. Army. Before the main U.S. Army contingent was sent out, Captain Stewart Van Vliet had been dispatched with a small group of men to pave the way for the new appointees to be introduced as leaders in the territory.

Van Vliet moved cautiously into the territory expecting little or no resistance (he had previous dealings with Mormons in Iowa). However, Young made it clear that he would not allow the new governor and federal officers to enter the territory. In response to the turmoil and confusion, Young had declared martial law in early August, but the proclamation hadn’t been widely circulated. Upon Van Vliet’s exit from Salt Lake City in mid-September, Young again issued the proclamation – now residents were more aware of the situation and the impending “invasion” by the U.S. Army.

In late September, the Utah militia began to have contact with the U.S. troops and employed delaying tactics and harassment such as burning grass along the Army’s trail or causing the Army’s cattle to stampede. In early October, Fort Bridger was burned down to prevent the Army from encamping there, and soon after that the militia and Army troops were involved in a skirmish in which no one was killed. By late October and into November, weather became a factor with the onset of heavy snowstorms. The Nauvoo Legion had also fortified Echo Canyon which led down to the Salt Lake Valley.

On November 21 the new territorial governor, Alfred Cumming, while on his way to Utah issued a proclamation declaring the residents of the territory to be in rebellion. Soon after a grand jury convened at Camp Scott where Brigham Young and sixty other men were indicted for treason. Meanwhile, there was little that could be accomplished now that winter weather had set in.

On November 21 the new territorial governor, Alfred Cumming, while on his way to Utah issued a proclamation declaring the residents of the territory to be in rebellion. Soon after a grand jury convened at Camp Scott where Brigham Young and sixty other men were indicted for treason. Meanwhile, there was little that could be accomplished now that winter weather had set in.

Back in August Young had contacted a perceived ally, Thomas Kane, who had previously been sympathetic to the Mormon’s plight in dealing with their ongoing controversies before they had headed west. Kane contacted President Buchanan and volunteered to serve as a mediator to resolve the conflict, but the President was concerned that if somehow the Mormons prevailed and destroyed his army, he would pay a heavy political price. Buchanan eventually agreed to allow Kane to attempt mediation so Kane made his way to Utah traveling first to Panama and then up to San Francisco (eventually landing in San Pedro, California because of heavy snow blocking Sierra passes). He was taken across through San Bernardino and Las Vegas and on to Salt Lake City.

Kane was successful in convincing Brigham Young to agree to the installment of Alfred Cumming as the new territorial governor. Kane traveled to Colonel Johnston’s winter encampment to escort Cumming into Salt Lake City in early March of 1858, and by mid-April Cumming had been installed as the new governor. However, tensions continued as there was still the possibility that the U.S. Army would enter Utah. Northern Utah settlers had already begun migrating south in March, boarding up their homes and, if necessary, burn their homes. Yet, even with Cumming’s successful installation, the migration continued.

In their book, The Story of the Latter-Day Saints, LDS historians James B. Allen and Glen M. Leonard noted the following:

It was an extraordinary operation. As the Saints moved south they cached all the stone cut for the Salt Lake Temple and covered the foundations to make it resemble a plowed field. They boxed and carried with them twenty thousand bushels of tithing grain, as well as machinery, equipment, and all the Church records and books. The sight of thirty thousand people moving south was awesome, and the amazed Governor Cumming did all he could to persuade them to return to their homes. Brigham Young replied that if the troops were withdrawn from the territory, the people would stop moving…. (p. 308)

Meanwhile, President Buchanan had come under increasing pressure from some members of Congress who did not want to start a war with the Mormons. Conversely, there were others who supported the efforts and even wanted to increase the size of the Army to deal with the situation. In April, the President sent a Peace Commission to negotiate a settlement, offering a pardon to all Mormons who had any involvement in the conflict with the U.S. government (or preventing the U.S. Army from entering the territory). The commissioners emphasized that the U.S. government did not want to interfere with the Mormons’ right to practice their religion.

Brigham Young eventually agreed to the terms of the proclamation but did not admit that Utah had ever been in direct rebellion of the U.S. government. Near the end of June, the U.S. Army troops made their way into Utah without any resistance. Soon after that, northern Utah settlers began to return to their homes and the army settled into a valley southwest of Salt Lake City. Eventually the troops moved out in 1861 as the Civil War began.

Buchanan’s Blunder

The conflict has been referred to as “Buchanan’s Blunder” in part because (1) Governor Young was not properly notified of his replacement, (2) troops were perhaps dispatched before knowing just how serious (or not) the Utah situation was, (3) supplies were inadequate and (4) the expedition was sent out too late and thus forced to encamp and wait out the winter of 1857-1858.

Aftermath and Consequences

The Mormons themselves lost out because of those who had their lives and livelihoods disrupted, and with the troop occupation the situation still remained tense – many of those troops reportedly reviled the Mormons. Another consequence of the Utah War was the creation of the Pony Express. The Utah militia, in their attempts to harass and keep out unwanted outsider intervention, had burned over fifty mail wagons. That business (Russell, Majors and Waddell) was never reimbursed by the federal government and in 1860 the Pony Express was created so they could obtain a government mail contract and avoid financial ruin.

The Utah War ultimately resulted in the decline of Mormon isolation. By 1869 the Transcontinental Railroad had been completed and with that came an influx of “Gentiles”. Polygamy still remained an issue with the federal government, but finally in 1896 Utah was granted statehood.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!