Tombstone Tuesday: America Virginia Palmer Bell (Lake City, Colorado)

America Virginia Palmer was born on June 11, 1848 in Cass County, Missouri to parents William Henry and Jane Francis (Cowherd) Palmer. The Palmer family is enumerated on the 1850 Census with William listed as a farmer with property worth $340 with three young children (America is one year old). By the 1860 Census William’s property has increased to $5,000 and now there are eight children ranging in age from seventeen to two – America was eleven years old.

America Virginia Palmer was born on June 11, 1848 in Cass County, Missouri to parents William Henry and Jane Francis (Cowherd) Palmer. The Palmer family is enumerated on the 1850 Census with William listed as a farmer with property worth $340 with three young children (America is one year old). By the 1860 Census William’s property has increased to $5,000 and now there are eight children ranging in age from seventeen to two – America was eleven years old.

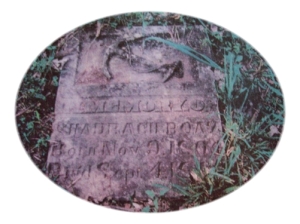

By 1870 I suspect the Palmer family had migrated to Colorado to pursue interests in silver mining, but I found no census record for them that year. In 1880 America had married (some family trees list the date of marriage as either August 15, 1871 or 1872) and was living in Crookeville, Hinsdale County, Colorado. Her husband Thaddeus P. Bell was listed as being forty-two years old and working in a silver mine. Jennie, as she was known, was thirty years old and kept house. Their daughter, baby Jennie, was listed as one month old(?). Baby Jennie, according to her gravestone died in 1879:

Another daughter, Mary Wilina, was born on August 27, 1880. On January 16, 1885 another child, Charles Jasper Bell, was born to Jennie and Thaddeus. On June 1, 1885 the Colorado State Census was taken and Thaddeus (T.P.) was still employed as a miner and Jennie keeping house. The couple has two young children: Mary W. who is listed as three years of age (should be five) and Charles J. who is four months old.

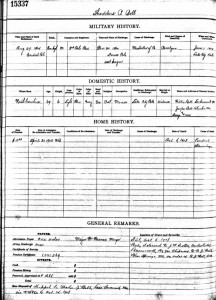

Jennie passed away on March 29, 1891 in Lake City, Hinsdale County, Colorado. The cause of death is not specifically known but a good guess would be influenza. About that time a wave of influenza was sweeping through the country and around the world. Other than Baby Jennie, there are no other family members buried in the Old Cemetery in Lake City, Hinsdale County, Colorado. It appears that her young children were sent back to Missouri to be raised and cared for by her parents (Jennie’s parents had relocated back to Missouri at some point). In the 1900 United States Census Jennie’s father William is listed as being seventy-six years old and living with him are Mary W. Bell age eighteen and Charles J. Bell age fifteen. I was not able to locate a 1900 census record for Thaddeus, although I found a United States Military Pension record — he was still living in Colorado and listed as “invalid” in 1902:

Jennie passed away on March 29, 1891 in Lake City, Hinsdale County, Colorado. The cause of death is not specifically known but a good guess would be influenza. About that time a wave of influenza was sweeping through the country and around the world. Other than Baby Jennie, there are no other family members buried in the Old Cemetery in Lake City, Hinsdale County, Colorado. It appears that her young children were sent back to Missouri to be raised and cared for by her parents (Jennie’s parents had relocated back to Missouri at some point). In the 1900 United States Census Jennie’s father William is listed as being seventy-six years old and living with him are Mary W. Bell age eighteen and Charles J. Bell age fifteen. I was not able to locate a 1900 census record for Thaddeus, although I found a United States Military Pension record — he was still living in Colorado and listed as “invalid” in 1902:

On October 6, 1908 Thaddeus died of a cerebral hemorrhage at the Veterans Home in Leavenworth, Kansas. This is a very interesting record, however. Thaddeus, who had been born in North Carolina, was sixty-nine years old at the time of his death. His body was shipped to his son C.J. Bell of Blue Springs, Missouri. According to a biography of Charles Jasper Bell, he graduated from the Kansas City (Missouri) School of Law in 1913 so it is likely that Charles was a student at the time. More on Charles a bit later… stay tuned.

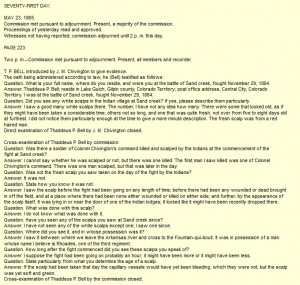

The most interesting part about Thaddeus’ military record (click photo above to enlarge) is this — Thaddeus was present at the Sand Creek Massacre (see this recent blog article), serving in the 3rd Colorado Cavalry under Colonel John Chivington. On the Veterans Home record there is an notation regarding his time and place of discharge – December 30, 1864 in Denver and listed as “asst surgeon”. This is particularly intriguing because I believe this is the gravestone of Thaddeus Bell in Blue Springs Cemetery, Blue Springs, Missouri. It matches the information listed on the Veterans Home record.

Regarding the Sand Creek Massacre, Thaddeus was called to testify and he recounted some gruesome details:

At one point in the testimony (not shown above) there is a reference to more specificallly “Dr. Thaddeus P. Bell”. I did find a record in the Directory of Deceased American Physicians, his specialty listed as “allopath”, often called “heroic medicine” (bloodletting, for instance) in the 19th century.

At one point in the testimony (not shown above) there is a reference to more specificallly “Dr. Thaddeus P. Bell”. I did find a record in the Directory of Deceased American Physicians, his specialty listed as “allopath”, often called “heroic medicine” (bloodletting, for instance) in the 19th century.

Maybe after leaving the military Thaddeus decided to head back to the mountains, become a silver miner, find a wife and start a family, leaving those gruesome memories behind. Why he stayed in Colorado after his wife’s death and why he sent his children away to be raised by her family is a mystery. But it does appear that he kept in contact with his children all those years since Charles was to receive his body for burial.

Now a little more about Charles Jasper Bell. After graduating from law school in 1913, he started his own practice. On September 12, 1918 Charles registered for the World War I draft and listed his occupation as attorney and his wife Grace was his nearest relative. From 1926 to 1930 Charles served as a member of the Kansas City, Missouri City Council. In 1931 he began serving as a circuit judge until 1934 when he resigned to run for Congress. He was elected as a Democrat to the Seventy-Fourth Congress and served six consecutive terms (1935-1949) before returning to his law practice. He died on January 21, 1978 and is buried in the same cemetery as his father in Blue Springs, Missouri.

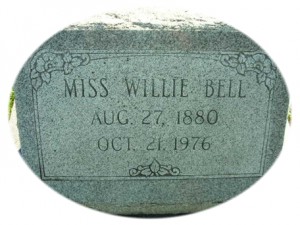

It appears that Mary Wilina Bell (known as “Willie”) never married — she is buried in the same cemetery as her father and brother:

So, I didn’t find a lot of specific information on Jennie (her given name “America Virginia” initially caught my eye) but found some very interesting stories about her husband and children — remember I just picked her randomly without knowing about these additional facts. I wonder if she could have ever imagined that her son would grow up to be a United States Congressman, serving with a future President (Harry S. Truman) in the Missouri delegation of Representatives and Senators?

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Mothers of Invention: Mary Anderson (Windshield Wiper)

Wintry and snowy weather is upon us early this year and one of the most essential devices in our cars is the windshield wiper. Alabama-born Mary Anderson was visiting New York City in 1902. The weather was sloppy and wet and trolley car drivers had to keep the windshield down, letting the cold and blustery weather in to the discomfort of driver and passengers alike.

Wintry and snowy weather is upon us early this year and one of the most essential devices in our cars is the windshield wiper. Alabama-born Mary Anderson was visiting New York City in 1902. The weather was sloppy and wet and trolley car drivers had to keep the windshield down, letting the cold and blustery weather in to the discomfort of driver and passengers alike.

She wondered if there might be a solution and began to sketch a design while still on the trolley. She returned home and after several attempts finally came up with a workable device – the wiper arms were made of wood and rubber attached to a lever near the steering wheel of the vehicle. Pulling the lever would move the arm back and forth in a fan shape and clear away rain or snow.

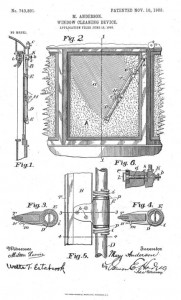

On November 10, 1903 Mary was granted a 17-year patent for a “window cleaning device for electric cars and other vehicles to remove snow, ice or sleet from the window” – Patent No. 743,801:

Mary attempted to sell the device to a Canadian manufacturer but was rejected – to them the device had no marketable value. In 1913, however, mechanical windshield wipers were included as standard equipment on all cars, but Mary Anderson never received any monetary compensation for her invention. In 1917 another woman, Charlotte Bridgewood, received a patent for the “Electric Storm Windshield Cleaner,” a device which used rollers instead of blades. Curiously, Charlotte’s daughter Florence Lawrence invented the turn signal. Charlotte, like Mary, never received any compensation for her invention.

Mary attempted to sell the device to a Canadian manufacturer but was rejected – to them the device had no marketable value. In 1913, however, mechanical windshield wipers were included as standard equipment on all cars, but Mary Anderson never received any monetary compensation for her invention. In 1917 another woman, Charlotte Bridgewood, received a patent for the “Electric Storm Windshield Cleaner,” a device which used rollers instead of blades. Curiously, Charlotte’s daughter Florence Lawrence invented the turn signal. Charlotte, like Mary, never received any compensation for her invention.

Mary Anderson was born in 1866 on Burton Hill Plantation in Greene County, Alabama. Mary moved to Birmingham in 1889 with her mother and sister, and Mary and her widowed mother built the Fairmont Apartment Building soon after arriving in Birmingham. From 1893 to 1898, Mary lived in Fresno, California and operated a cattle ranch and vineyard. Mary Anderson remained single her entire life and died on June 27, 1953 at her summer home in Tennessee at the age of 87.

Interesting Update: This Fox News story mentions that the windshield wiper, invented in 1903, may become obsolete.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Surname Saturday: Sparhawk

The surname “Sparhawk” is derived from the Middle English name “Sparhauk” or “Sparrowhawk” which was derived from the Old English name of “Spearheafoc”. The name is also thought to have been a nickname for someone resembling a sparrow-hawk.

The Sparhawk family is one of the oldest and well-known in New England. Lewis Sparhawk, born in Dedham, Essex, England in approximately 1530, is the first English ancestor who can be connected to the American branch of the family line. Church records show that Lewis Sparhawk married Elizabeth Bayning in Dedham on February 17, 1560. Their children were named: Patience, Nathaniel, Daniel, Clement and Samuel. I noticed that the names “Samuel” and “Nathaniel” are common as the ancestral line progresses.

Samuel, son of Lewis, was born in Dedham in approximately 1565. His children were named: Daniel, John, Lewis, Nathaniel, Mary, Benjamin and Clement. Nathaniel, the fourth child of Samuel’s, was baptized on February 16, 1598 and the spelling variations surrounding the record of that event were: “Sparhawke”, “Sparhauk”, “Sparhauke”, “Sparohauke”, “Sparrowhauke” and “Sparrow Hawke”. Nathaniel(1) was the first Sparhawk emigrant ancestor of the American Sparhawk line.

Nathaniel(1) arrived in Cambridge, Massachusetts sometime in 1636 and was admitted as a freeman there on May 23, 1639.

To be admitted as a freeman had nothing to do with servitude in early colonial days, but simply that the person was then a full citizen and had the right to hold public office and participate fully in civic affairs, including payment of taxes. Qualifications included:

Swear allegiance to the Crown

Be a male at least 21 years of age

Church membership

Own personal property valued at least £40

Possess a quiet and peaceable demeanor

Be endorsed by fellow freemen

The Freeman’s Oath (in Modern English):

I ________being by gods providence, an Inhabitant, and Freeman, within the Jurisdiction of this Commonwealth; do freely acknowledge myself to be subject to the Government thereof: And therefore do here swear by the great and dreadful Name of the Ever-living God, that I will be true and faithful to the same, and will accordingly yield assistance and support there unto, with my person and estate, as in equity I am bound; and will also truly endeavor to maintain and preserve all the liberties and privileges thereof, submitting myself to the wholesome Laws and Orders made and established by the same. And further, that I will not plot or practice any evil against it, or consent to any that shall so do; but will timely discover and reveal the same to lawful Authority now here established, for the speedy preventing thereof.

Moreover, I do solemnly bind myself in the sight of God, that when I shall be called to give my voice touching any such matter of this State, in which Freemen are to deal, I will give my vote and suffrage as I shall judge in mine own conscience may best conduce and tend to the public weal of the body, So help me God in the Lord Jesus Christ.

Nathaniel(1) became a leading citizen of Cambridge and a deacon in his church. In 1642 records show he possessed five houses and five hundred acres of land (by his death he owned at least one thousand acres). In 1639 he was granted permission to sell wine and strong water. His first wife, Mary, died in 1643 or 1644 and Nathaniel(1) married Katherine ?. Nathaniel(1) died on June 28, 1647 at the age of fifty years; his wife Katherine died a week later on July 5. His oldest child, Nathaniel(2), was born in Dedham in approximately 1630 so he was possibly six years old when he arrived in Cambridge with his family.

Nathaniel(2) was also a distinguished citizen of Cambridge, serving as selectman for nine years, and as a deacon in his church. He married Patience Newman on October 3, 1649, she being the daughter of Reverend Samuel Newman (author of the Newman Concordance). Nathaniel(2) and Patience had seven children, two of them named “Nathaniel” – Nathaniel(3) died as a very young infant and Nathaniel(3a) was baptized on November 3, 1667. The other children born to them were: Mary, Sybil, Esther, Samuel and John (the subject of this week’s Tombstone Tuesday article).

Nathaniel(2) was also a distinguished citizen of Cambridge, serving as selectman for nine years, and as a deacon in his church. He married Patience Newman on October 3, 1649, she being the daughter of Reverend Samuel Newman (author of the Newman Concordance). Nathaniel(2) and Patience had seven children, two of them named “Nathaniel” – Nathaniel(3) died as a very young infant and Nathaniel(3a) was baptized on November 3, 1667. The other children born to them were: Mary, Sybil, Esther, Samuel and John (the subject of this week’s Tombstone Tuesday article).

Continuing where I left off Tuesday with Reverend John(1) Sparhawk, he and his wife Priscilla had two sons: John(2) and Nathaniel who were young children at the time of their father’s death in 1718. John(2) graduated from Harvard University in 1731 and became pastor of a church in Salem, Massachusetts. John, like his father, died in his forties on April 30, 1755.

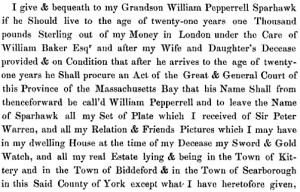

John(1)’s youngest son, Nathaniel, was born on March 27, 1715 and later became a successful businessman in Boston. In the social circles in which Nathaniel moved, he met his future wife, Elizabeth Pepperell who was the only daughter of Colonel William Pepperell (later Sir William) of Kittery, Maine. Colonel Pepperell sent away to London for his daughter’s dress, the ceremony was held in Kittery and he gave the newlyweds a new home. Nathaniel’s brother John had this to say about his younger brother’s marriage (click to enlarge):

Nathaniel opened a mercantile house in Kittery but also continued pursuing his business interests in Massachusetts. In Kittery, Nathaniel participated in civic affairs, becoming a justice of the peace in 1744-45 and in 1746 he represented the town of Kittery in the General Court of Massachusetts Bay. Later his father-in-law was promoted to general and received the title of Sir William Pepperell, traveling to London to meet with King George II in 1749. Nathaniel, by this time, had also taken on the position of special justice in York and had turned over his business interests to a clerk. He had also received a commission and served as a colonel in the militia.

The French war was costly and taxes had been raised (as high as two-thirds of income), and in 1758 Nathaniel was bankrupt and experienced financial embarrassment. As a result of Sir William’s death in 1759 Nathaniel was appointed to fill the vacancy of justice of the Inferior Court of Common Pleas for York County, an office Nathaniel served in until 1772. Nathaniel died in Kittery on December 21, 1776, intestate.

Nathaniel and Elizabeth had seven children, two of them dying young. The first child, William Pepperell died young, followed by Nathaniel, another William Pepperell, John (died young), Andrew Pepperell, Samuel Hirst and Mary Pepperell. Sir William requested in his will that upon his death his grandson William Pepperell Sparhawk take his name “William Pepperell” and leave the name of Sparhawk (click to enlarge):

Thus in October 1774, William Pepperell Sparhawk assumed his grandfather’s name and title (Sir William Pepperell, Baronet). However, he soon fell into disfavor over disagreements with fellow colonists who were then beginning to contemplate breaking away from England (William considered himself a Royalist). To avoid conflict, William sailed to England (his wife died on the voyage) and was well received, later becoming one of the founders of the British and Foreign Bible Society. However, in 1778, back in America, he was officially banished. He died in London in December 1816.

This is just one fascinating branch of the Sparhawk family tree. Sparhawks continued to immigrate to America from England, settling throughout the colonies and beyond. By 1920 the Sparhawk name was most prevalent in Massachusetts and Pennsylvania, with five to eight percent of recorded family names in Ohio, Missouri, Wisconsin and Nebraska.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Ghost Town Wednesday: Washoe, Montana

The land in Carbon County, Montana which eventually grew into this company mining town was purchased in 1903 by Fred and Annie Bartels. Carbon County had been created out of portions of Park and Yellowstone Counties in 1895, and so named for the rich coal deposits in the area.

The land in Carbon County, Montana which eventually grew into this company mining town was purchased in 1903 by Fred and Annie Bartels. Carbon County had been created out of portions of Park and Yellowstone Counties in 1895, and so named for the rich coal deposits in the area.

In 1906 the Anaconda Copper Company purchased the land which was situated at the foot of the Beartooth Mountains near the headwaters of the Bearcreek river. Although I couldn’t locate an exact map location of Washoe, I assume it lies somewhere between Bearcreek (town) and Red Lodge.

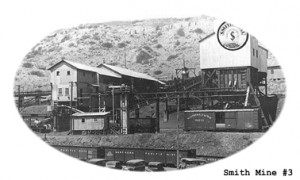

Anaconda Copper Mining Company and its subsidiary, Washoe Coal Company, developed the land into a company mining town, presumably to provide coal to the Anaconda mining operations in Anaconda and Butte. The name “Washoe” was a Nevada Indian tribal name and even today that name is seen on buildings and landmarks in Anaconda. In 1907 a post office was built and residents of Washoe (approximately 950), nearby Smith Mine and Scotch Coulee received mail in Washoe. Daily shipments of twelve hundred tons of coal left Washoe via the Northern Pacific Railroad.

Washoe was no different than most company mining towns – a company store, community hall and company housing were built. The first school was held in 1907 in one of the houses on Company Row and later a two-story school building was built near the company store with eight rooms, bell tower, playground and outhouses. The school burned down and classes were again held on Company Row until a new brick building replaced it in 1924. The school closed in 1955 and is now a private residence.

Washoe was no different than most company mining towns – a company store, community hall and company housing were built. The first school was held in 1907 in one of the houses on Company Row and later a two-story school building was built near the company store with eight rooms, bell tower, playground and outhouses. The school burned down and classes were again held on Company Row until a new brick building replaced it in 1924. The school closed in 1955 and is now a private residence.

Other buildings in the town included a church, teacherage, boarding houses, and train depot. Even though residents did not own the land they still built their own homes. The Women’s Club of Washoe purchased one of the homes for club meetings and it was also used for Sunday school and regular church services when a minister was available.

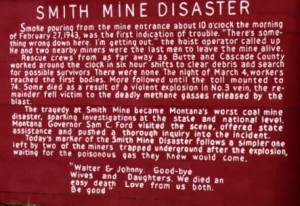

By 1936 the town began to decline because Anaconda no longer required coal for their smelting operations (in 1912 the Montana Power Company had been established in Butte — electricity was less expensive). On February 27, 1943, the worst mining disaster in Montana history occurred at the nearby Smith Mine #3, operated by the Montana Coal and Iron Company. That day was a Saturday and there were only 77 men working the mine that day – being paid time and a half for weekend work. World War II dominated the world news and miners who had in recent years experienced the Great Depression were eager to work and contribute to the war effort.

According to Matt Stump of Montana State University Billings (Billings Gazette – February 26, 2013), the miners were quite patriotic. While doing research for his senior thesis, he discovered records indicating that one miner, a native of Austria, increased his bi-weekly purchase of war bonds from $75 to $132. The crew had just over an hour and half earlier descended approximately seven thousand feet underground to begin work.

No one is sure exactly what caused the explosion but it was likely due to an unusually high buildup of methane gas. The explosion was powerful enough to blow a 20-ton locomotive off the tracks, although the site of the explosion was so deep it wasn’t detected at the mine entrance. Smoke began pouring from the entrance and sirens sounded, bringing both family members and emergency crews to the site.

The Bureau of Mines reported that 30 miners were killed instantly in the explosion and the rest died later as a result of injuries or suffocation from carbon monoxide and methane fumes. Rescue efforts began immediately as telephone line was strung down the mine shaft to enable communications with crews on the surface. While some family members remained hopeful of their loved ones being rescued, it soon became apparent that would not be possible. On March 7 the last body was removed – mine foreman Elmer Price aged 53, who left behind a widow and five children.

According to the Billings Gazette, a few miners lived long enough to scribble farewell messages to their families:

“Goodbye wifes and daughters. We died an easy death. Love from us both. Be good.”

“We try to do our best but couldn’t get out.”

“It’s five minutes pass 11 o’clock. Dear Agnes and children I am sorry we had to go this way — God bless you all.”

There were 58 widows and 125 fatherless children left behind. Many miners were buried in the Bearcreek cemetery.

Coupled with the devastating explosion and the eventual cessation of railroad operations in 1953, coal mining was no longer a viable enterprise. A few residents still live in the area – the Washoe Quilt Shop web site indicates when everyone is home there are 21 residents. Nearby, Smith and Scotch Coulee mine buildings remain standing, albeit dilapidated, while the Washoe mine buildings were long ago torn down and the land reclaimed. The area is located between Belfry and Red Lodge on Highway 308.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Tombstone Tuesday: Reverend John Sparhawk – Bristol, Rhode Island

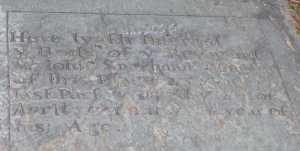

“Here lyeth interred the body of the Reverend Mr. John Sparhawk minister of this place 23 years last past and dyed the 29th of April, 1718 in the 46th year of his age.”

This is the epitaph of Reverend John Sparhawk, buried at the Congregational Cemetery in Bristol, Bristol County, Rhode Island.

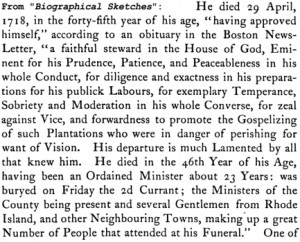

According to his biography in Biographical Sketches of Graduates of Harvard University: In Cambridge, Massachusetts, Volume 3, John Sparhawk was born in “1673?” (most sources believe his birth year was either 1672 or 1673) in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

John’s parents were Nathaniel and Patience Sparhawk. Patience was the daughter of Reverend Samuel Newman of Rehoboth, who was also the author of the Newman Concordance. Because the following information is an important part of John Sparhawk’s heritage, I want to elaborate a bit on his grandfather’s life and accomplishments before continuing with John’s story.

Samuel Newman was born in May of 1602 in Banbury, Oxfordshire, England. One note of interest – Samuel’s parents were Richard Newman and Susan Sparhawk Newman. At age 16 he entered Oxford and graduated with honors from Trinity College in 1620. He was then ordained to serve in the Church of England, but was later prosecuted for non-conformity. In 1636, Samuel and his wife Sibbell (Featly) immigrated to Massachusetts with their children, arriving in Dorcester and later settling in Bristol.

Samuel Newman was born in May of 1602 in Banbury, Oxfordshire, England. One note of interest – Samuel’s parents were Richard Newman and Susan Sparhawk Newman. At age 16 he entered Oxford and graduated with honors from Trinity College in 1620. He was then ordained to serve in the Church of England, but was later prosecuted for non-conformity. In 1636, Samuel and his wife Sibbell (Featly) immigrated to Massachusetts with their children, arriving in Dorcester and later settling in Bristol.

In 1644, Newman traveled with several of his parishioners to found the town of Rehoboth, Massachusetts. Newman was said to be a remarkable man. Reverend Richard Mather said of Newman, “He loved his church as if it had been his family, and taught his family as if it had been his church.” According to Mather, Newman’s Concordance was prepared in the wilderness and “properly called a Herculean labor”. The first edition was published in London in 1643 and after moving to Rehoboth Newman worked to improve it before the revised edition was printed in 1650.

John’s father, Nathaniel Sparhawk, was a man of wealth and a deacon in the Cambridge church, as well as a town Selectman. After all his debts were settled, Nathaniel left an estate of £700, careful to provide for his wife and son John. He provided the following in case Patience remarried after his death (The Genealogical Magazine: 1907 – New England):

It appears that John was well thought of by his father and thus well provided for. John graduated from Harvard in 1689, receiving a Master of Arts degree. According to The Genealogical Magazine, “[H]is part at graduation was the negation of the proposition ‘An Bona Intentio sufficiat ad Bonitatem Actionis’.” His fellow classmates went on to become merchants, ministers, a military commander and a judge.

John was invited to preach at Bristol, Rhode Island, a town of prominent and wealthy families, on October 6, 1693. The first offering he received on October 8 was £1 2s (one pound, two shillings). On September 19, 1694 records show that the congregation:

Voted, that for the love & honor we bear to the Rev. John Sparhawk, & in hopes of his speedy settlement among us, we do hereby promise to pay him by weekly contribution or otherwise the sum of £70 per annum whilst he remains a single man, & £80 per annum when he comes to keep a family. (Biographical Sketches…, p. 421)

By the laying on of hands of the presbytery (pastors of neighboring churches), John Sparhawk was ordained the pastor on June 12, 1695 and remained there until his death in 1718. Several sources indicate that during John’s life he did not enjoy robust health (and perhaps that’s why his father made special mention of provision for him in his will). Another minister noted in 1717 that “Mr. Sparhawk preaches now but seldom.” On July 16, 1717 a committee had been chosen to provide assistance to carry on public worship for the period of three months.

His obituary was full of praise for a steadfast and faithful man:

John Sparhawk had been married two or three times and his wife at the time of his death, Priscilla, survived him by several years. John had at least two sons: John and Nathaniel Sparhawk. According to Abstracts of Bristol County, Massachusetts probate records (Genealogical Publishing Company, 1987), p. 4:

Will of John Sparhawk, Minister of the Gospell in Bristol, “being Sick & very Weak”, dated 28 Apr 1718, probated 15 Mar 1726/27, mentions wife Priscilla [executrix] and 2 sons John & Nathaniel Sparhawk [both under 21].

Priscilla remarried (Jonathan Waldo) and lived until 1755. She died near the home of her son, Nathaniel, in Kittery, Maine.

It is apparent that John Sparhawk had a rich spiritual heritage (and an interesting surname). This Saturday I will begin a new series of articles called “Surname Saturday” (I should note the name is not original as I’ve recently found other genealogy and history blogs who write under the same title on Saturdays). So, this Saturday’s article will be a continuation of the story of the Sparhawk family — and maybe some more on Samuel Newman since his mother was also a Sparhawk.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Home Remedies and Quack Cures (and a “Royal Touch”): Curing Consumption

It’s known by various names – most commonly tuberculosis, but at times throughout history referred to as: “consumption” because the patient experienced severe weight loss and was almost literally “consumed” with the disease; phthisis (derived from Latin-Greek phthinein meaning to waste away); scrofula or Pott’s disease; White Plague (making patients appear pale).

Evidence of tuberculosis has been found in both human and animal remains known to be between 15,000 to 20,000 years old. Egyptian mummies were infected with the bacterium and Hippocrates identified “phthisis” as one of the most widespread diseases of his time, observing that autumn was a particularly bad time of the year for persons with consumption.

Evidence of tuberculosis has been found in both human and animal remains known to be between 15,000 to 20,000 years old. Egyptian mummies were infected with the bacterium and Hippocrates identified “phthisis” as one of the most widespread diseases of his time, observing that autumn was a particularly bad time of the year for persons with consumption.

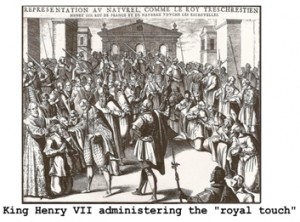

Tuberculosis in the Middle Ages was known as “scrofula” which affected the lymph nodes. Alternatively it was known as “king’s evil” because it was thought to be curable by the touch of royalty. In King Henry VII’s time, the diseased were given amulets or charms to wear that had been “touched” by the King. Charles II may have touched as many as 90,000 victims between 1660 and 1682. By 1712 the practice had declined in England but continued in France until around 1830.

In eighteenth century Europe the disease killed 900 out of every 100,000 persons. Contributing factors were poor sanitation, malnutrition and overcrowded conditions. During this epidemic the disease became known as the “White Plague”. By the next century, it was discovered that the disease was communicable so the idea of isolating patients came about through the use of “sanatoriums”. The first sanatorium was founded in the United States in 1884 by Edward Livingston Trudeau.

In eighteenth century Europe the disease killed 900 out of every 100,000 persons. Contributing factors were poor sanitation, malnutrition and overcrowded conditions. During this epidemic the disease became known as the “White Plague”. By the next century, it was discovered that the disease was communicable so the idea of isolating patients came about through the use of “sanatoriums”. The first sanatorium was founded in the United States in 1884 by Edward Livingston Trudeau.

In isolating patients from society, a sanatorium provided rest, improved nutrition and the chance to recover. These institutions were most widely used before the discovery of either vaccines or antibiotics to treat the disease. Locations in the dry and arid American West were among the most popular because it was thought that drier air was more helpful for the patient than the more humid climes in other parts of the country.

For the wealthy, sanatoriums were set up to run more like what we call a “spa” today. Arizona, and specifically Tucson, was the most popular location – boasting twelve such hotel-like facilities by the early 1900’s. At one point there were so many people who had come to Arizona that tent cities sprang up to house the sick – many sleeping in the open desert. One such location was near what is now central Phoenix, called Sunnyslope, where tents were pitched along the mountainside north of the city.

Quack Cures

Before a vaccine and antibiotic treatments were discovered or widely used, however, there was widespread use of so-called consumption cures or nostrums, or as I like to call them “quack cures”. Given the seriousness of the disease and its characteristic weakening and wasting of a patient, these so-called “miracle treatments” came to be seen as cruel in their promises to cure the diseased.

One such cure extensively advertised was “Addiline” and typically the ad would have a picture of a person when they were ill and before taking Addiline, one after taking Addiline and one taken as “latest photo”. Another version of the ad heralded “I CURED MYSELF OF TUBERCULOSIS” – and, of course, it was only available by mail order.

According to the Journal of the Outdoor Life, The Anti-Tuberculosis Magazine (December 1920), the usage of Addiline was compared to the foolishness of a child thinking he could catch a bird by putting salt on its tail (Putting Salt on the Germ’s Tail, by Philip P. Jacobs, PhD). Addiline was purported to act as a germicide, in effect overcoming the germs (bacilli). From the Addiline booklet:

Addiline3A laboratory affiliated with the Journal conducted an analysis of Addiline and found it to be comprised of “petroleum oil with a certain amount of pine oil or oil of thyme, possible a mixture of several essential oils”. A leading tuberculosis researcher made the following observation:

The effect of these oils on tuberculosis would of course be fatal . . . In fact it is a great deal like the Frenchman and the flea powder: if you can catch the flea and put the powder on him, you can certainly commit homicide! The same thing might happen to the tubercle bacillus if he should happen to fall into this Addiline oil.

The Ohio State Board of Health did its own analysis and found it to contain petroleum and turpentine oil which essentially cost about 35 cents, but sold for $5.00 – what a profit margin! The Journal referred to Addiline’s composition as nothing more than Russian oil – a common remedy for constipation “or for other diseases that need a powerful and steady cleanser of the bowels”.

The accompanying booklet advised that often after taking Addiline one would experience belching – but not to worry because that was actually beneficial, you see, because that brought the remedy (via vapors) up into the lungs to directly attack the tuberculosis germs! It was the opinion of the Journal that there was no physical possibility for that sort of benefit to be derived. In their opinion, “[L]ong before any such germicidal effect would be experienced, the patient would be in condition for the undertaker.”

The guarantee issued by the Addiline Medicine Company claimed that upon receipt of $5.00 they would send a four-week “trial treatment”. If at the end of four weeks the patient would sign a statement saying no benefit was derived from faithfully following the directions (the company also suggested that the patient follow the practice of good nutrition, adequate rest, etc.), then a refund would be issued. The Journal article pointed out that it was an established fact that tuberculosis patients who were given a so-called cure and strongly believing it to be a cure, would most certainly feel better (psychologically) after taking the treatment.

An experiment had been conducted in New York where tuberculosis patients were intravenously administered a “cure” which really was just milk and water. And lo and behold many patients seemed to recover almost immediately – less coughing and reduced fevers. Eventually organizations like the National Vigilance Committee of the Associated Advertising Clubs of the World began to address the issue of fake advertising in order to give a better impression of advertising as being good and useful for the general public. An analysis done by chemists affiliated with the organization had their own (humorous) conclusion in regards to Addiline: “[I]t would make a better furniture polish than tuberculosis remedy”.

Legitimate Cures

By the end of World War II major medical advances to treat the disease were made when a vaccine known as “BCG” came to be more widely used. In 1944 scientists discovered that streptomycin could be effectively used to treat tuberculosis. In the years following other treatments were developed which led to a significant decline of the disease until the 1980’s when the disease began to experience a resurgence. Contributing to that resurgence was the emergence of HIV and drug-resistant strains of tuberculosis.

Thank goodness modern medicine has better tools today to deal with the disease than a quack cure from the early twentieth century that would have made a “better furniture polish than tuberculosis remedy”.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Feudin’ and Fightin’ Friday: Graham-Tewksbury Feud (Bovine vs. Ovine)

This range war conducted in the 1880s, sometimes called The Pleasant Valley War or Tonto Basin Feud, was anything but pleasant. It turned out to be one of the more bloody and vicious feuds in American history, certainly in Arizona history. So fierce and violent was this feud that Zane Grey memorialized it in his book “To the Last Man”.

The feud pitted the Graham family (joined by the Blevins family) against the Tewksbury family – the Grahams were cattlemen and the Tewksburys were cattlemen who supported the sheepherders. The Tewksbury family worked as sheepherders for the Dagg Brothers who owned a large sheep ranch. As early as 1882 tensions began to arise over grazing and water rights and property boundaries, continuing for several years. Some of the conflict was fueled by personal distaste for the other side – the Tewksburys were half Indian. Plus, cattlemen just didn’t like sheepherders.

The feud pitted the Graham family (joined by the Blevins family) against the Tewksbury family – the Grahams were cattlemen and the Tewksburys were cattlemen who supported the sheepherders. The Tewksbury family worked as sheepherders for the Dagg Brothers who owned a large sheep ranch. As early as 1882 tensions began to arise over grazing and water rights and property boundaries, continuing for several years. Some of the conflict was fueled by personal distaste for the other side – the Tewksburys were half Indian. Plus, cattlemen just didn’t like sheepherders.

The feud pitted the Graham family (joined by the Blevins family) against the Tewksbury family – the Grahams were cattlemen and the Tewksburys were cattlemen who supported the sheepherders. The Tewksbury family worked as sheepherders for the Dagg Brothers who owned a large sheep ranch. As early as 1882 tensions began to arise over grazing and water rights and property boundaries, continuing for several years. Some of the conflict was fueled by personal distaste for the other side – the Tewksburys were half Indian. Plus, cattlemen just didn’t like sheepherders.

In the 1880s cattle rustling had become a huge problem in the area known as Tonto Basin, and the Graham and Blevins families were suspects. One of the first disputes arose when cattle belonging to James Stinson were stolen. As tensions escalated, the Tewksburys began to side with the sheepherders and protect the Dagg Brothers’ sheep. The conflict wasn’t just between the Grahams and Tewksburys – other ranchers had similar issues with sheep grazing on grassland meant for their cattle, so the entire valley eventually became involved. The deadly part, though, was between the Grahams and Tewksburys.

In the 1880s cattle rustling had become a huge problem in the area known as Tonto Basin, and the Graham and Blevins families were suspects. One of the first disputes arose when cattle belonging to James Stinson were stolen. As tensions escalated, the Tewksburys began to side with the sheepherders and protect the Dagg Brothers’ sheep. The conflict wasn’t just between the Grahams and Tewksburys – other ranchers had similar issues with sheep grazing on grassland meant for their cattle, so the entire valley eventually became involved. The deadly part, though, was between the Grahams and Tewksburys.

In February of 1887 a Navajo man who was employed by the Tewksburys was killed while herding sheep in an area known as Mogollon Rim – very close to the area where sheep were not supposed to be grazing. Tom Graham shot and killed the man and destroyed the herd of sheep. The bloody part of the war had begun.

In February of 1887 a Navajo man who was employed by the Tewksburys was killed while herding sheep in an area known as Mogollon Rim – very close to the area where sheep were not supposed to be grazing. Tom Graham shot and killed the man and destroyed the herd of sheep. The bloody part of the war had begun.

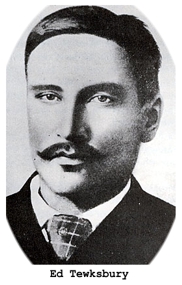

Later that year in August, William Graham was shot and killed at his home, living long enough to identify Ed Tewksbury as his killer. Ed had already fled into the hills, but a trial was held despite his absence – even so the jury found him guilty. Just a few weeks later in September, John Tewksbury and William Jacobs were gunned down by the Grahams in front of one of their cabins. The Grahams remained and continued firing at the cabin for hours, stopping only when John’s wife came out with a shovel to bury the dead.

The Blevins family were drawn into the spotlight when Andy Blevins bragged around the town of Holbrook that he had killed Tewksbury and Jacobs. Holbrook Sheriff Commodore Perry Owens already had a warrant for Blevins’ arrest for cattle rustling so it seemed like a good time to go ahead and bring him in. On September 4, the Sheriff attempted to arrest Andy Blevins but Andy refused to interrupt his Sunday dinner. Andy’s half-brother John opened the door and took a few shots at the Sheriff, who immediately returned fire, hitting John and Andy both.

Fifteen year-old Sam Blevins shot at the Sheriff, as did Mose Roberts who was a Blevins family friend. The Sheriff escaped unscathed, but Andy and Sam Blevins and Mose Roberts were dead, while John Blevins was wounded. The gunfight made Sheriff Owens a legend, but it didn’t save his job – the county later fired him.

Commodore Perry-275Another sheriff and his posse soon caught up with Tom and John Graham and Charles Blevins in Prescott. Sheriff Mulverson demanded the trio surrender but instead a gunfight ensued – when it was over John Graham and Charles Blevins lay dead and Tom Graham escaped. Murders and lynchings continued, none of them ever solved.

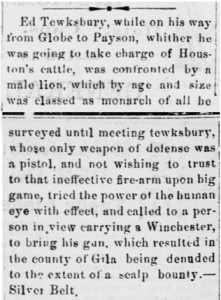

The feud finally came to an end when Tom Graham was shot in Tempe – before dying he identified the shooter as Ed Tewksbury. Ed was arrested and tried twice – the first trial resulted in a hung jury. In the second trial he was convicted but because of some legal technicality the verdict was deferred, and in 1895 the case was dismissed. So, Ed Tewksbury was the last man standing and he got way with murder not just once, but twice. I found a couple of stories about Ed tangling with bears and lions – if true, he was one tough hombre:

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Ghost Town Wednesday: Bara-Hack, Connecticut

Obadiah Higginbotham and Jonathan Randall and their families moved from Cranston , Rhode Island to the land situated on the outskirts of Pomfret, Connecticut in an area called “Ragged Hills”. Obadiah and Jonathan were both of Welsh descent and named their settlement “Bara-Hack” which meant “breaking of bread”. One source suggested that their migration occurred at a time when the British were battling along the Rhode Island coast. The story goes that Obadiah was a deserter from the British Army, so he may have been stationed in Cranston and met his wife Dorcas there.

Obadiah Higginbotham and Jonathan Randall and their families moved from Cranston , Rhode Island to the land situated on the outskirts of Pomfret, Connecticut in an area called “Ragged Hills”. Obadiah and Jonathan were both of Welsh descent and named their settlement “Bara-Hack” which meant “breaking of bread”. One source suggested that their migration occurred at a time when the British were battling along the Rhode Island coast. The story goes that Obadiah was a deserter from the British Army, so he may have been stationed in Cranston and met his wife Dorcas there.

It is believed the Higginbothams moved to Connecticut sometime before 1780, as did the Randall family. There may also have been some sort of familial connection between the two families because there is a Randall-Botham Cemetery in Pomfret. At least two of their daughters and Dorcas are buried there – Phebe died at age 19 and Rhoda at age 30. Dorcas died at the age of 100.

According to Early Homesteads of Pomfret and Hampton, the Randall family was quite well-to-do and had many slaves whom they brought with them to Connecticut. Some of the slaves are said to have been buried in the family burial grounds (Find-A-Grave only lists nine interments but perhaps many of the graves are unmarked or have never been enumerated. I wish more had been listed and photographed though.). The slaves believed that ghosts sat in an elm tree near the cemetery at night, so they would never venture out after dark.

According to Early Homesteads of Pomfret and Hampton, the Randall family was quite well-to-do and had many slaves whom they brought with them to Connecticut. Some of the slaves are said to have been buried in the family burial grounds (Find-A-Grave only lists nine interments but perhaps many of the graves are unmarked or have never been enumerated. I wish more had been listed and photographed though.). The slaves believed that ghosts sat in an elm tree near the cemetery at night, so they would never venture out after dark.

Obadiah soon built a cabin on a bluff above the stone bridge he also built. According to Early Homesteads:

The walls and cellar of this house show the finest workmanship. There was a great stone chimney in the center, which the elements have never disturbed. Near the broad south doorstone remains the old well and leach stone where the ash barrel stood, for leaching the lye Dorcas used in making her soft soap. The fields he cleared and cultivated lie open upon the sunny hill.

Obadiah built a waterwheel and small mill along Nightengale Brook where he and Jonathan operated a business known as Higginbotham Linen Wheels. They made flax wheels (spinning wheels) and sold them to neighboring towns.

Obadiah built a waterwheel and small mill along Nightengale Brook where he and Jonathan operated a business known as Higginbotham Linen Wheels. They made flax wheels (spinning wheels) and sold them to neighboring towns.

The land and home were passed down through the generations, but at some point the family name was shortened to “Botham”. It is said that as late as the Civil War sheep still roamed the pastures and were washed at shearing time in the mill pond behind the stone bridge.

It is thought that perhaps Washington and Lafayette’s armies camped on one tract of Randall’s land and that both generals returned to the area and spent the night at Grosvenor House in Pomfret and had breakfast at the Randall house.

The Randall house, like Obadiah’s, was handed down to succeeding generations. In 1840, George Randall, Jr. manufactured shoes in a shop next to the house. The shoes were marketed in Southbridge and George employed several people. The last Randall to live in the house was Betty Randall who died in 1893, the last person to be buried in the cemetery.

The Randall house, like Obadiah’s, was handed down to succeeding generations. In 1840, George Randall, Jr. manufactured shoes in a shop next to the house. The shoes were marketed in Southbridge and George employed several people. The last Randall to live in the house was Betty Randall who died in 1893, the last person to be buried in the cemetery.

As the Randall and Higginbotham families died and business declined, the settlement was abandoned. Bara-Hack became an interesting place to explore when tales of ghosts brought the curious. According to ConnecticutHistory.org:

Visitors to Bara-Hack claimed they heard voices, sounds from domesticated animals, and noises made by ghostly horse-drawn buggies passing by. In addition, newspapers reported sightings of bright orbs and streaks of light swirling over the cemetery. Researchers even found records of the most common sighting, that of a infant apparition reclining in a tree, reported by slaves of the Randall family hundreds of years earlier.

Paul Eno, a paranormal researcher, went to the site in 1971 to investigate and reported seeing a bearded face hover over the cemetery (did Obadiah have a beard!?!). Some called Bara-Hack the “Village of Voices”. The attention brought many visitors to the site, but today the settlement is on private property and closed to the public.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Tombstone Tuesday: Shadrach Boaz

Shadrach Boaz (a strong Bible name!) was born on November 9, 1809 in Pittsylvania County, Virginia to Thomas and Lucinda (Davis) Boaz. I came across his name while researching another “Shadrach”. His family history is interesting so immediately following is some background information before proceeding with the story of Shadrach’s life.

Shadrach Boaz (a strong Bible name!) was born on November 9, 1809 in Pittsylvania County, Virginia to Thomas and Lucinda (Davis) Boaz. I came across his name while researching another “Shadrach”. His family history is interesting so immediately following is some background information before proceeding with the story of Shadrach’s life.

This article is no longer available at this site. However, it will be enhanced and published later in a future issue of Digging History Magazine, our new monthly digital publication available by individual purchase or subscription. To see what the magazine is all about you can preview issues at our YouTube Channel. Subscriptions are affordable, safe and easy to purchase and the best deal for getting your “history fix” every month.

This article is no longer available at this site. However, it will be enhanced and published later in a future issue of Digging History Magazine, our new monthly digital publication available by individual purchase or subscription. To see what the magazine is all about you can preview issues at our YouTube Channel. Subscriptions are affordable, safe and easy to purchase and the best deal for getting your “history fix” every month.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Military History Monday: Sand Creek Massacre

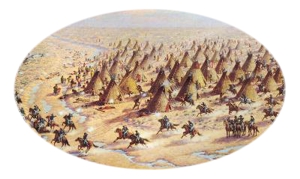

One hundred and forty-nine years ago, on November 29, 1864, perhaps the most atrocious and disturbing attacks in United States military history occurred at Sand Creek, an encampment in Colorado Territory of 700-800 Cheyenne and Arapaho Indians. The attack was led by John Milton Chivington, a particularly fierce and staunch abolitionist who also happened to be an ordained Methodist minister.

One hundred and forty-nine years ago, on November 29, 1864, perhaps the most atrocious and disturbing attacks in United States military history occurred at Sand Creek, an encampment in Colorado Territory of 700-800 Cheyenne and Arapaho Indians. The attack was led by John Milton Chivington, a particularly fierce and staunch abolitionist who also happened to be an ordained Methodist minister.

John Milton Chivington

John Milton Chivington was born in Ohio in 1821. John was five years old when his father died, leaving John and his brothers to run the farm. Even though he had only been able to attend school sporadically, by the time he married in 1844 he had been running a timber business for several years. Although not a religious person, he became interested in Methodism and in 1844 he was ordained as a Methodist minister.

In 1853 he worked with a missionary to Wyandot Indians in Kansas. At this time, Kansas and Missouri were embroiled in a de facto civil war over the issue of slavery. John Chivington was a strict abolitionist in pro-slavery Missouri and he ruffled more than a few feathers. Members of his congregation even wrote a letter instructing him to stop preaching.

The next Sunday congregants came to church intending to tar and feather him – Chivington, however, walked up to the pulpit with his Bible and two pistols. He declared, “By the grace of God and these two revolvers, I am going to preach here today”. He soon became known as the “Fighting Parson”. The Methodist Church sent Chivington to Nebraska where he stayed until 1860, when he was named the presiding elder of the Methodist Rocky Mountain District. He moved to Denver, built a church and started Denver’s first Sunday School. It has been said that when he preached his booming voice could be heard three blocks away!

The next Sunday congregants came to church intending to tar and feather him – Chivington, however, walked up to the pulpit with his Bible and two pistols. He declared, “By the grace of God and these two revolvers, I am going to preach here today”. He soon became known as the “Fighting Parson”. The Methodist Church sent Chivington to Nebraska where he stayed until 1860, when he was named the presiding elder of the Methodist Rocky Mountain District. He moved to Denver, built a church and started Denver’s first Sunday School. It has been said that when he preached his booming voice could be heard three blocks away!

When the Civil War erupted the Colorado Territorial Governor William Gilpin offered Chivington a commission as a chaplain, an offer which Covington turned down. He was not interested in a “praying commission” – he wanted a “fighting” commission. In 1862 Major John Chivington, serving under Colonel John Slough, led troops of the Colorado 1st Volunteers on a forced march to Fort Union, covering 400 miles in just 14 days – an astounding feat in that day.

Colonel Slough was ordered by Colonel Edward Canby (Fort Union’s ranking officer) to remain at Fort Union; however, Slough disobeyed orders and headed to Glorieta Pass to engage Confederate forces led by Colonel William Read Scurry and Major Charles Pyron. Initially the battle was somewhat indecisive, but would later turn into a decisive Union victory. The Battle of Glorieta Pass would later become known as the “Gettysburg of the West”.

The Confederates had encamped at one end of the pass near Johnson’s Ranch. After battling for a couple days with the result being somewhat of a “draw”, Colonel Slough ordered a flanking maneuver. Chivington was accompanied by Lt. Colonel Manuel Chaves of the New Mexico Volunteers. Chaves’ scouts had spotted the Confederate supply train encamped at Johnson Ranch so Chivington positioned his troops above the ranch, watching and waiting. After about an hour they began descending to the encampment, surprising the small Confederate force guarding the supplies.

Major Chivington ordered the destruction of eighty supply wagons, some containing flammable liquids and ammunition – horses and mules were also killed. Someone later remarked that Chivington gave the commands with a “perverse glee”. To save bullets, the animals were killed by bayonet. The casualties incurred in the previous days’ battles, and the damage inflicted with the destruction of the Confederate supply train, gave the Union a decisive victory, and Pyron and his troops soon began to retreat back to Texas. Chivington was acclaimed as a military hero.

Chivington returned to Denver where he turned an eye toward politics. A strong advocate for Colorado statehood, he hoped to run for the state’s Congressional seat. Colorado was growing and so too was the conflict between the white man and the Cheyenne. Newspapers helped to fan the flames:

Self preservation demands decisive action and the only way to secure it is to fight them in their own way. A few months of active extermination against the red devils will bring quiet and nothing else will. – Daily Rocky Mountain News – August 10, 1864

That same day, the Weekly Rocky Mountain News endorsed John Chivington for Congress. Blustery as he tended to be, Chivington challenged the territorial governor to decisively deal with the Cheyenne, declaring “the Cheyennes will have to be roundly whipped — or completely wiped out — before they will be quiet. I say that if any of them are caught in your vicinity, the only thing to do is kill them.” A few weeks later Chivington was addressing a group of church deacons and said, “[I]t simply is not possible for Indians to obey or even understand any treaty. I am fully satisfied, gentlemen, that to kill them is the only way we will ever have peace and quiet in Colorado.”

Sand Creek Massacre

In November of 1864, just a few months after speaking out in favor of killing Cheyennes, Chivington led a regiment to the Sand Creek reservation. Earlier Chief Black Kettle had traveled to Fort Lyon to meet with officials and agreed to make peace. He and his group of Southern Cheyenne settled in Sand Creek, assured that they would not be considered hostile any longer by the government. In fact, an American flag and a white truce flag flew over the encampment.Black Kettle_et alBefore Chivington led his troops to Sand Creek many of them had been drinking, further inflaming the situation. Although he observed the American and white truce flags, Chivington ordered an attack on the unsuspecting Cheyenne. After several hours of fighting the death toll stood at somewhere between 150 to 200 Cheyenne massacred, while comparatively only a handful of Chivington’s troops were killed, some reportedly by friendly fire (perhaps due to the drunkenness). Most of the Cheyenne killed were women and children. To add to the horror, many bodies were mutilated and scalped – soldiers cut off fingers and ears for the jewelry and as “souvenirs”.

Initially, Chivington was hailed as a hero and a parade was held in Denver in his honor. But then reports began to surface of drunken soldiers butchering defenseless women and children. Chivington had six members of his regiment arrested and charged with cowardice in battle – the six soldiers had refused to participate in the massacre and were now reporting the atrocities. The Secretary of War arranged their release and ordered them to Washington to testify before Congress.

One of the six, Captain Silas Soule, a close personal friend of Chivington’s, was shot in the back and killed in Denver before he could testify. Court martial charges were eventually brought against Chivington, but by that time he was no longer a member of the military and could not be punished under military law. Criminal charges were never filed either. However, an Army judge summarized it well: “a cowardly and cold-blooded slaughter, sufficient to cover its perpetrators with indelible infamy, and the face of every American with shame and indignation.”

Chivington wasn’t criminally or militarily punished for his deeds, but he was forced to resign the militia and banned from Colorado politics – unable even to participate in the push for statehood. He moved to Nebraska, lived briefly in California and then returned to Ohio to run a small newspaper. He tried politics again in 1883 but withdrew when stories about his participation in the Sand Creek Massacre surfaced. He returned to Denver and served as a deputy sheriff for a short time before dying of cancer in 1894.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!