Off the Map: Ghost Towns of the Mother Road – Glenrio, Texas (and New Mexico)

This ghost town was originally named “Rock Island” but was later changed by the Rock Island and Pacific Railroad to “Glenrio” or “Glen Rio”. The name was a curious choice, however, since “glen” means “valley” and “rio” means “river” – neither of those geographical features are anywhere near this town that sprung up in the early 1900’s.

This ghost town was originally named “Rock Island” but was later changed by the Rock Island and Pacific Railroad to “Glenrio” or “Glen Rio”. The name was a curious choice, however, since “glen” means “valley” and “rio” means “river” – neither of those geographical features are anywhere near this town that sprung up in the early 1900’s.

The area was opened to farmers for settlement as early as 1905 with 150-acre tracts of land for sale. A railroad depot was established the following year, and with farmers and ranchers settling in the area, freight and cattle shipments and the introduction of farming created the need for other businesses.

The area was opened to farmers for settlement as early as 1905 with 150-acre tracts of land for sale. A railroad depot was established the following year, and with farmers and ranchers settling in the area, freight and cattle shipments and the introduction of farming created the need for other businesses.

This article has been enhanced and published in the June 2018 issue of Digging History Magazine. Other articles in this issue include: “On a Whim and a Bet: America’s First Coast-to-Coast Road Trip”, “Victorian Pastimes: Girdling the Globe”, “Victorian Fashion: Bicycles, Bloomers and Suffrage”, and more. Preview the issue here or purchase here.

This article has been enhanced and published in the June 2018 issue of Digging History Magazine. Other articles in this issue include: “On a Whim and a Bet: America’s First Coast-to-Coast Road Trip”, “Victorian Pastimes: Girdling the Globe”, “Victorian Fashion: Bicycles, Bloomers and Suffrage”, and more. Preview the issue here or purchase here.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Tombstone Tuesday: The Preacher Sons of Enoch and Tabitha Holton

Enoch Holton was born on October 19, 1796 in North Carolina, and his wife Tabitha Pipkin was born on November 28, 1796. Enoch and Tabitha married on April 2, 1822 and had a family of at least five children (my estimates):

Enoch Holton was born on October 19, 1796 in North Carolina, and his wife Tabitha Pipkin was born on November 28, 1796. Enoch and Tabitha married on April 2, 1822 and had a family of at least five children (my estimates):

Elvira (1823 or 1824)

Jesse Walker Pipkin (1826)

Tabitha (1830)

Isaac Pipkin (1833)

Alonzo Jerkins (1837)

The Holtons were a deeply religious family and of the Free Will Baptist faith until they, along with others of the same faith became part of the Disciples of Christ, which at the time was attracting congregants from both the Free Will Baptists as well as the “Regular Baptists”. The transition appears to have taken place for the Holton family in the late 1830’s or early 1840’s. The Broad Creek Church was established by Henry Smith on January 6, 1844 in Craven County (later Pamlico County), and Enoch Holton was the first Elder of the church.

The Holtons were a deeply religious family and of the Free Will Baptist faith until they, along with others of the same faith became part of the Disciples of Christ, which at the time was attracting congregants from both the Free Will Baptists as well as the “Regular Baptists”. The transition appears to have taken place for the Holton family in the late 1830’s or early 1840’s. The Broad Creek Church was established by Henry Smith on January 6, 1844 in Craven County (later Pamlico County), and Enoch Holton was the first Elder of the church.

The Disciples of Christ movement arose out of disagreements over leadership and perhaps the rigidness of other denominations in regards to such things as baptism and communion. According to North Carolina Disciples of Christ: A History of Their Rise and Progress, and of Their Contribution to Their General Brotherhood, their slogan was “Back to Christ”. The establishment of the Disciples of Christ was an outgrowth of the so-called “Restoration Movement” with an emphasis on Christian education and an appeal to worship with both one’s head and heart.

The Holton sons took their faith very seriously and became ordained ministers (and farmers) – in 1927 one son was the oldest living Disciples of Christ minister in North Carolina, another was known as the “walking preacher” and another known as a “singing master”.

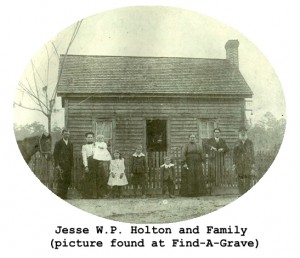

Jesse Walker Pipkin Holton

Jesse was born on April 28, 1826, the first son of Enoch and Tabitha. According to a biographical sketch written by George T. Tyson following Jesse’s death, Jesse was born into a humble Christian home. He was uneducated but learned to read and write.

On July 1, 1849, Jesse confessed his sins and was baptized by Henry Smith. In 1850 Jesse was still single and enumerated for the 1850 Census as a laborer living in Craven County. On January 19, 1854, Jesse married Barbara Eleanor Bennett, daughter of William and Barbara Brinson Bennett.

Jesse preached his first sermon (of many) on February 1, 1858 at his home church. On August 9, 1858 Jesse was “set apart to the ministry” and ordained by J.B. Respess. Jesse began his ministry and was listed as a “minister” on the 1860 census, along with Barbara and three children:

Jesse preached his first sermon (of many) on February 1, 1858 at his home church. On August 9, 1858 Jesse was “set apart to the ministry” and ordained by J.B. Respess. Jesse began his ministry and was listed as a “minister” on the 1860 census, along with Barbara and three children:

Jesse was likely both a farmer and a minister since in 1870 he is enumerated as a farmer and in 1880 as a preacher/farmer. In 1880 the children of Jesse and Barbara are listed as Sarah, Tabitha, Enoch, Jesse, Alexander and Barby, just one year old. The last census to enumerate Jesse Holton was in 1900 when he was still a farmer at the age of 74 years. He and Barbara had been married for 47 years.

George Tyson wrote his tribute to “Uncle Jesse” in the October 7, 1904 issue of the Disciples of Christ Watch Tower publication:

Uncle Jesse was familiar with the Bible. He told me he had read the New Testament through as many times as the number of years he had been engaged in the ministry.

Through rain and sunshine, through summer’s heat and winter’s cold he has gone for forty-six years, more than four-fifths of this time on foot. For thirty-eight of those years he had no team. His longest pastorate was a Bay Creek Church, for which he preached eighteen years, and never missed a visit. There was not a year during his ministerial life but that he had the care of one or more churches. He was a good preacher; but, perhaps, his strongest characteristic was his daily walk, modest in manners, and chaste in conversation. For forty-six years he has preached, in church, in school-house, in barns, and in homes; of righteousness, temperance and the judgment to come, calling people to repentance. His life was an exemplification of the gospel which he preached. His Christian life was faithful to the end, his faith unwavering from his baptism to death. And for all of this his compensation fell far behind in affording sustenance. He told me just a short while before his death that he “preached the gospel for the love of the gospel.” Not in state, but in church, his counsel was often sought.

Jesse’s first sermon was in 1858 and his last sermon, a “funeral discourse,” was preached about a month before he died on August 9, 1904. In January of that year, Jesse and Barbara had celebrated fifty years of marriage.

Isaac Pipkin Holton

Isaac was born on January 24, 1833, the second son of Enoch and Tabitha. Isaac became a Christian at the age of 22 and was baptized on July 4, 1855 by Gideon Allen. He was ordained as a minister of the Christian Church in 1861 by William Dunn, Japtha Holton (his uncle I believe) and J.W. Holton (Jesse).

Isaac volunteered to join the Confederate Army on January 24, 1862. At the time of the first muster he was listed as “absent – sick”. On March 23, 1862, the records indicate that Isaac “deserted in Craven Co.”.

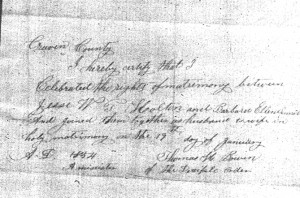

Perhaps Isaac was not well-suited to Army life. On May 31, 1865, Isaac married Rebecca Ann Robinson in front of a Justice of the Peace in Craven County. Their first child, Enoch Tyson, was born in 1865 – perhaps this was a “shotgun wedding”(!?)

Isaac was enumerated as a farmer in 1870 and he and Rebecca then had three children: Enoch (5), Mary (3) and Tomlin (1). Curiously, in 1880 they have another daughter named “Mary F.” (in addition to the Mary enumerated in 1870) and one named “Mecora B.” Isaac continued to work as a farmer.

For the last census before his death in 1907, Isaac still worked as a farmer. He was a part-time minister and farmer following his conversion and ordination, according to George Tyson’s biographical sketch:

Bro. Holton was deprived of school advantages, but he was endowed with more than average natural ability, loved literature and read much. He was familiar with the Bible from the beginning of Genesis to the end of Revelation. He read many books and was especially fond of poetry. A day or two before his death, prostrate on his bed, he repeated and sang one or two hymns and preached a short sermon, using for his text, “If a man die, shall he live again?” Bro. Isaac did not give his full time to the ministry, however he did a great deal of preaching and singing (he was a singing master) until the latter years of his life. Two years before his death he had the care of a church. He was called upon to preach a great many funerals. He delivered a funeral address only about a year before his death.

Bro. Holton was one of the most active and energetic of men; a good conversationalist; and his home “given to hospitality.”

Isaac died on November 10, 1907 and was buried in Pamlico County. His wife Rebecca lived until 1916.

Alonzo Jerkins Holton

Alonzo was the youngest son of Enoch and Tabitha, born on July 20, 1837. It appears that Alonzo was perhaps named after either a family friend or relative. I found a reference to an Alonzo T. Jerkins of Cravens County who signed a bond for a negro boy in 1855.

Alonzo married Mary Frances Holton on July 21, 1860 with Jesse performing the ceremony. Whether Mary Frances was a cousin or had been married before to another Holton I do not know. Something, however, must have happened to Mary Frances because on September 19, 1867 he married Mary Jane Lewis – Isaac officiated that ceremony.

On January 1, 1866, the Broad Creek Church had been reorganized and Isaac was chosen as the pastor and Clerk; Alonzo was chosen assistant Clerk. On October 9, 1866, Alonzo was ordained to the ministry at Broad Creek. His father Enoch had died on June 9, 1865 and in 1870 Tabitha, aged 74, was living with Alonzo and Mary Jane, along with their two young children Alexander (2) and Augustus (1). Alonzo was a farmer.

In 1880 Alonzo and Mary Jane’s family had grown, adding children Ella, Isaac, Minnie and Cally. Alonzo was then occupied as both a preacher and a farmer. He had apparently become more active in ministry as he had joined the North Carolina Christian Missionary Society in 1877. In 1871, he had preached at the Antioch Convention, and “Brother Holton acquitted himself well.” In 1877 he again spoke at the annual convention and his ministry was chronicled:

On Friday night we had the pleasure of hearing Brother A.J. Holton, who preached an earnest, zealous and pathetic discourse. This is the first time I ever heard Brother Holton. I was pleased with his efforts. I have understood that much of his time is employed on his farm, which prevents him from doing what he might do under different circumstances.

Alonzo’s family continued to grow. By 1900 he and Mary Jane had added three more children: Cornelia (19), Wilford H. (16) and Hattie E. (12). Alonzo continued to farm, but according to the Chalice News, a newsletter of the First Christian Church in Richland, North Carolina, Alonzo served as pastor of that church in 1891 – as noted above he did more farming, presumably to make a living and feed his family.

In 1910, at age 72, he was still a farmer and only Hattie remained at home with her parents. His primary occupation in 1920, however, was “Preacher” and his industry was “Gospel” – he was 82 and Mary Jane 76 years old. In 1930, at the age of 92 he was still preaching, a clergyman in the Christian Church according to that year’s census.

On January 1, 1935, at the age of 97, Alonzo Jerkins Holton passed away and was buried in the Alonzo Holton Cemetery in Pamlico County. Mary Jane passed away in 1937. On his tombstone, the inscription reads: “I hope to see my pilot face to face when I have crossed the bar.”

At the time of his death he was one of the two surviving members of the original North Carolina Christian Missionary Society members. According to the Pamlico Profile, “he read the Bible religiously; a large part of his money was spent for books; he died saying he had no grudge against any person.”

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Surname Saturday: Kerfoot

The surname Kerfoot (or alternately spelled Kearfott), like many other surnames, was a locational name and would have meant “dweller at the hill-slope at the foot of the hills (or valley)” or simply a family who lived at the foot of a hill or in a valley. Surnames such as Kerfoot were used by those who lived near some landscape feature like a hill, valley, tree, etc.

As with most early surnames, there were spelling variations including: Kyrfytt, Kearfott, Kerfut, Carefoot, Carefoote, Cearfoot, Kerfoote and Kearfoote, just to name a few. There was one instance of the same soldier, William Kearfott, whose name was spelled three different ways on the historical register of Virginians in the Revolutionary War – Carefeet, Karfatt and Kerfoot.

A quick search at Find-A-Grave yielded these surnames: Carefoot, Carefoote, Kerfoot, Kearfoot, Kerfott and Kearfott. The most reliable records regarding the first Kerfoot to land in America appear to be those researched in Kerfoot, Kearfott and Allied Families in America (KKAFA). The history of that family is taken from that volume and summarized below.

According to KKAFA, there were at least three family branches in North America – one in Virginia in the mid-1700’s, one in Lancaster, Pennsylvania in 1818 and another one in Canada around 1820. These three branches are believed to have migrated from Ireland. Earlier colonial records indicate the presence of a Thomas Kerfitt (1624) who came over as an indentured servant and Elizabeth Kerfoote (1637), another indentured servant. “Margaret Kearfoote, of Wigan, (Lancashire) spinster, bound to Ezekiel Parr for 4 Yeares” appears on the ship Concord’s passenger list in 1638.

According to KKAFA, there were at least three family branches in North America – one in Virginia in the mid-1700’s, one in Lancaster, Pennsylvania in 1818 and another one in Canada around 1820. These three branches are believed to have migrated from Ireland. Earlier colonial records indicate the presence of a Thomas Kerfitt (1624) who came over as an indentured servant and Elizabeth Kerfoote (1637), another indentured servant. “Margaret Kearfoote, of Wigan, (Lancashire) spinster, bound to Ezekiel Parr for 4 Yeares” appears on the ship Concord’s passenger list in 1638.

One record indicates “Thos. Buttler, Son of Wm. Butler, (bound) to Ganther Carefoot for 4 Yeares.” According to KKAFA and at the time of that research, no additional mention of Ganther Carefoote was found – no land or grant records in Virginia, Maryland or Pennsylvania from 1701 until William Kerfoot bought a plantation in 1763. From William Kerfoot onward the records appear to be the most reliable and considered by many as the founder of that family in Virginia.

William Kerfoot

It has been presumed that William Kerfoot immigrated to Virginia from Ireland, bringing with him his wife and three sons. The first evidence of his presence in Frederick County is shown on a deed for 192 acres of land along the Opequon Creek – the name on the deed was William Carefoot. The Kerfoots, along with the Glasses, Allens and Vances were named as the earliest settlers of this region of Virginia in A History of the Valley of Virginia by Samuel Kercheval.

William Kerfoot’s house was said to have been:

… sturdily built of logs after the fashion of pioneer dwellings, with doors and blinds of strong batten work made of double layers of wood strongly fastened with hand wrought nails. The strength of the doors suggest that they have been constructed with an eye to defences again the Indians who remained a menace to the settlers for some years after 1750.

The Kerfoot family were of the Baptist faith, although it is not known if they practiced that faith before arriving in America. When the Kerfoots settled in that area, Indian attacks were not uncommon. According to KKAFA, the Church of England relaxed its standards to allow what the termed “dissenters” to populate the Shenandoah Valley. Quakers came from Pennsylvania and a group of Baptists came from New Jersey and persecution ensued:

The Kerfoot family were of the Baptist faith, although it is not known if they practiced that faith before arriving in America. When the Kerfoots settled in that area, Indian attacks were not uncommon. According to KKAFA, the Church of England relaxed its standards to allow what the termed “dissenters” to populate the Shenandoah Valley. Quakers came from Pennsylvania and a group of Baptists came from New Jersey and persecution ensued:

A particular victim of the Church’s wrath was the Rev. James Ireland, an eloquent and power Baptist preacher who performed the marriage ceremony for many of the Kerfoots during this period. It is related that the English authorities decided to “eliminate the Baptist from their midst” and that a Mrs. Sutherlin bribed her negro servant to poison the Ireland family. William Kerfoot, a member of Ireland’s congregation, was active in finding the poison and in securing the perpetrators of the attempt for trial. Ireland recovered only to meet imprisonment and fresh attempts upon his life.

This served to make the Baptists more determined to defend their faith and the right to worship as their consciences dictated. The Virginia branch of the Kerfoot family have largely remained true to the Baptist faith with family members serving in various leadership capacities within the denomination and local churches.

William and his wife Margaret had seven children: George, William, Samuel, Margaret, Elizabeth, Sarah and Mary. His name appears in court records, including law suits, at various times up until his death in 1779. His son George had preceded him in death in 1778.

In the first version of his will, William gave land to his remaining sons William and Samuel and ordered that the part of his plantation where George’s widow lived be sold “at publick vendue and the money arising by the sale thereof to be equally divided between my four daughters Margaret, Elizabeth, Sarah and Mary and each of them to have an equal share of my stocks as before mentioned and also an equal share of all my Household goods.” Samuel also received William’s “negro boy, Will” as part of his inheritance. About four months after the first will was signed, William revised his will and, instead of selling the land she lived on as stipulated in the first will, he changed his mind:

Peggy Kerfoot, widow of my late son, George, decsd, in consideration of natural love and affection and for the better enabling her to support her children and also for the sum of £1500, current money, a tract of land whereon the said Peggy now lives and all my other lands on that side of the Opequon, notwithstanding any will or bequest heretofore made.

It appears that his daughter Margaret perhaps never married or was married somewhere else other than Frederick County. Elizabeth, married twice, had no children. Sarah had eight children, two of them unmarried. Mary was the youngest daughter who married Arthur Carter, he from a prosperous Quaker family that had migrated from Bucks County, Pennsylvania to the Shenandoah Valley. Mary and Arthur had fifteen children – five died in infancy, however.

George’s children did quite well. Son John was one of the most prosperous farmers and land owners, his sons and daughters well provided for. His daughter Catherine married George Lewis Ball, whose family were ancestors of both George Washington and General Robert E. Lee. Descendant John David Kerfoot migrated to Texas, but upon hearing of the war between the states returned to his native Virginia and joined Lee’s Northern Virginia army. After the war he helped his father restore the plantation and then returned to Texas to later become mayor of Dallas.

Farther down the branch line, descendants of George Kerfoot served in World War II – one fought at Iwo Jima and Okinawa and saw the flag hoisted at Iwo Jima, another was a doctor in a Japanese prisoner camp, who on August 1, 1945 “observed an enormous white cloud in the distance which rose to tremendous height.”

William Kearfott

The spelling of surnames was so varied and uncertain in colonial times, but the gravestone of William Kerfoot’s second son’s gravestone is inscribed with “William Kearfott” and thus his descendants use that spelling. As noted above, records indicate various spellings of his name even on Revolutionary War records.

William married Mary Bryarly after the war ended and they had two children, William and Mary, before Mary died shortly after the second birth. His second marriage produced no more children. William Kearfott was perhaps the wealthiest of the three brothers, as evidenced by the taxes he paid on his various properties. William died on February 4, 1811.

His granddaughter Evaline Kearfott married Nickolas Coday, a cousin of Colonel William F. Cody, a.k.a. “Buffalo Bill”. His descendants fought and some died in the Civil War – one lived in Richmond and was a close friend of General and Mrs. Robert E. Lee. Of course, as it happened many times during the Civil War, families were divided in their loyalties. William’s son took his family, except for one son who was already a successful surveyor in Virginia, to Ohio. The Ohio Kearfoots fought for the Union and those who were still in Virginia for the Confederates. The two sons of John Piercall Kearfoot (who remained in Virginia) made their way through Union lines to visit their father only to find a Union solder already there – their first cousin from Ohio.

Samuel Kerfoot

Samuel had two sons, William S. Kerfoot and Samuel Kerfoot II. William served during the War of 1812 and remained in Virginia. Samuel, however, migrated to Kentucky in 1820 and in 1824 married Margaret Ann Lampton, sister of Jane Lampton Clemens and mother of Samuel Clemens, a.k.a. Mark Twain.

His descendants became more adventurous and continued to move further west. Great-grandsons Marion Munroe Kerfoot, George Henry Kerfoot and John Samuel Kerfoot participated in the “Oklahoma Run” in 1889 when the “Cherokee Strip” was opened for settlement, thus becoming pioneers of the Oklahoma Territory. They opened dry-goods and grocery stores and were among the founders of the town of El Reno.

Thus the descendants of William Kerfoot of the Shenandoah Valley became part of the fabric of America – they fought wars, built prosperous businesses, became doctors, ministers and educators, and were witnesses to world-changing events.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Feisty Females: Kate Gleason

Catherine Anselm “Kate” Gleason, like her good friend Lillian Moller Gilbreth, was an engineer and businesswoman long before those career choices were considered appropriate for a woman to pursue. Her father left Ireland in 1848, three years after the potato famine, married and had a son and then lost his wife and one-year old daughter to tuberculosis. The family had been living in Chicago, but William returned to Rochester following his wife and daughter’s death to work at a machine shop and study mathematics at night school. He married Ellen McDermott, also an Irish immigrant, at the age of twenty-seven. Kate was born on November 25, 1865 in Rochester.

Catherine Anselm “Kate” Gleason, like her good friend Lillian Moller Gilbreth, was an engineer and businesswoman long before those career choices were considered appropriate for a woman to pursue. Her father left Ireland in 1848, three years after the potato famine, married and had a son and then lost his wife and one-year old daughter to tuberculosis. The family had been living in Chicago, but William returned to Rochester following his wife and daughter’s death to work at a machine shop and study mathematics at night school. He married Ellen McDermott, also an Irish immigrant, at the age of twenty-seven. Kate was born on November 25, 1865 in Rochester.

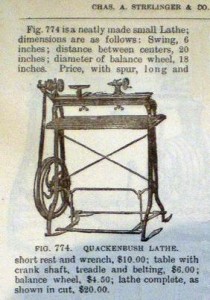

William established a machine shop with some other men and in 1867 he patented a device that held tools in a metal-working lathe – he called it Gleason’s Patent Tool Rest. When he and his partners disagreed on the direction of the company, William left and joined Kidd Iron Works as a supervisor. In 1875, William took over the company and renamed it Gleason Works. His oldest child, Tom, was his right-hand man.

William established a machine shop with some other men and in 1867 he patented a device that held tools in a metal-working lathe – he called it Gleason’s Patent Tool Rest. When he and his partners disagreed on the direction of the company, William left and joined Kidd Iron Works as a supervisor. In 1875, William took over the company and renamed it Gleason Works. His oldest child, Tom, was his right-hand man.

Kate attended an all-girls Catholic school, Nazareth Academy. She is said to have resisted the stereotype of the day that girls were second best. She remarked later, “Girls were not considered as valuable as boys; so I always jumped from a little higher barn, and vaulted a taller fence than did my boy playmates, just to prove that I was as good as they.” At age nine she was reading books on machinery and engineering, hardly subjects that were considered appropriate for a young girl.

Kate was eleven years old when Tom died of typhoid fever, a shocking blow to his family and the company. At the age of twelve Kate began working for her father, first as his bookkeeper and later “tinkering” in the machine shop and running the office.

In 1884, Kate became the first woman to ever enter the engineering program at Cornell University. She excelled but Gleason Works was struggling financially as companies were failing and unable to pay their bills, a result of the recession which occurred between 1882 and 1885. Her father wrote to ask her to return for a year to assist him.

In 1884, Kate became the first woman to ever enter the engineering program at Cornell University. She excelled but Gleason Works was struggling financially as companies were failing and unable to pay their bills, a result of the recession which occurred between 1882 and 1885. Her father wrote to ask her to return for a year to assist him.

Kate never returned to Cornell, but took night classes at the Mechanics Institute in Rochester, studying mechanical engineering. Again she was running the office at Gleason Works and traveling to the Midwest to sell the machinery. At age twenty-five, Kate she was officially named the Secretary-Treasurer of the newly reorganized Gleason Tool Company. According to Jan Gleason, wife of Kate’s grand-nephew James:

… it was her business and sales sense that grew the company. Kate convinced her father to concentrate on their bevel gear planer, a machine that made gears which could work on a bend. Their machine made gears faster and cheaper than any competitor’s. Beveled gears were a very important part of the fast-growing bicycle industry, and a major contributor to the rapidly expanding auto industry. (Women of Steel and Stone: 22 Inspirational Architects, Engineers and Landscape Designers)

Even without a degree, Kate was quite accomplished and knowledgeable in the field of mechanical engineering. Not only was she able to explain the processes of the products she was selling, she also possessed a breadth of knowledge about the engineering processes of the companies she was selling the products to. Fred Colvin, machinist and author, gave her the title “the Madame Curie of machine tools”.

At age twenty-nine her doctor recommended some rest and relaxation in Atlantic City, but Kate decided to board a cattle steamer and head across the ocean to Great Britain and Europe, the only woman passenger on the ship. By the time she arrived she felt better and set out to visit potential clients in Scotland, England, Germany and France. It was a successful trip with several large orders secured and Gleason Works became part of the first wave of American businesses to expand overseas.

Rochester played a major role in the women’s suffrage movement and Kate was undoubtedly influenced by it, perhaps emboldening her to step out and pursue non-traditional roles. Susan B. Anthony, a resident of Rochester, cast votes along with fourteen other women in the 1872 elections – she was later arrested for breaking a federal law. At age twenty-two Kate joined a business women’s club, the Fortnightly Ignorance Club, of which Anthony, a friend of her parents, was a member as well.

Susan Anthony had given Kate some advice early in her life, “[A]ny advertising is good. Get praise if possible, blame if you have to. But never stop being talked about.”

Anthony gave Kate set of books, History of Woman Suffrage, in 1903 and inscribed it with the following: “Kate Gleason, the ideal business woman of who I dreamed fifty years ago – a worthy daughter of a noble father.” Susan Anthony died a few months later at the age of eighty-six.

So impressive was Kate’s knowledge of the machine and tool industry, her father’s invention of the bevel gear planer was sometimes credited to her (even Henry Ford did so). Kate left Gleason Works in 1913, some say due to a family conflict and/or gender discrimination. After thirty-five years with her family’s company she began to work for Ingle Machine Company.

She received accolades and prestigious awards through the years of her illustrious career. In 1913 she was elected to the German Engineering Society, followed by election into the American Society of Mechanical Engineers. At an ASME dance a few months later, she was the only woman among four thousand men at the event.

When Ingle Machine Company experienced financial setbacks, Kate was appointed receiver by a bankruptcy court and later restored the company to solvency. Two years after going into receivership owing $140,000, the company was worth over one million dollars at the conclusion of the proceedings. Then came World War I, and one of her friends, the president of First Bank of East Rochester, was called to duty overseas. By a unanimous vote, Kate Gleason was elected president of the bank, the first woman (without benefit of family ties) to head a national bank and holding the position until 1919 when the war ended.

For years she had a vision for low-cost housing to be constructed in East Rochester and had bought land with that project in mind. Her first projects were turning a swamp into a park and designing and engineering a country club called Genundawah. With the end of World War I came a “wedding boom” – hundreds of soldiers returning to marry their sweethearts and there was a housing shortage. Kate’s plans were for a community to be built called “Concrest”.

The community would resemble a French village and she would employ the use of concrete instead of wood and bricks. The plans were standardized, and even with the use of mostly unskilled workers, one hundred six-room cement houses were efficiently and economically built. It gained her another prestigious membership in the American Concrete Institute, and again she was the first woman member.

Kate helped to restore the war-torn French village of Septmonts, and after leaving Rochester she headed to South Carolina to develop a resort in Beaufort. Later she started a development in Sausalito, California. On January 9, 1933, however, Kate Gleason died of pneumonia. Even after departing Rochester, it was still her home and she was buried there. The Rochester Institute of Technology as well as other institutions, libraries and parks in the Rochester area were recipients of her generosity at the time her personal fortune of over one million dollars was distributed.

Lillian Gilbreth, her long-time friend, was said to have received money from Kate’s estate. In the book Lillian Gilbreth – Redefining Domesticity, it was noted of their friendship:

A memorable visit to Rochester, New York, brought her together for the first time with a rare woman engineer by the name of Kate Gleason. Lillian had never met a woman like her – an unmarried middle-aged construction expert, who thought it perfectly appropriate to climb up the side of a steam engine to drive it and to not bother with traditional feminine clothing on construction sites.

And from the book, Women of Steel and Stone: 22 Inspirational Architects, Engineers and Landscape Designers:

Frank and Lillian Gilbreth occasionally consulted with Gleason Works. On one trip, Kate and Lillian sat in the cab of a small steam engine, and Kate showed Lillian how to run it. Kate applied Frank and Lillian’s time and motion techniques to the construction of Concrest houses and saved considerable time and money. Kate and Lillian also sailed together on the Scythia from New York on Thursday June 19, 1924, five days after Frank’s death. Lillian quickly scheduled a daily four o’clock tea in the Garden Lounge for all the ladies on the ship. Libby Sanders, Lillian’s companion, wrote in her diary, “A fascinating person, Miss Gleason, held the stage. She is the jolliest and most adorable person. She knows all there is to know about building houses.” Kate, Lillian and Libby were traveling companions in Europe and also sailed home together, returning to New York in August 1924. Kate and Lillian also traveled together to the World Engineering Congress in Tokyo in 1929. The women were such good friends that Kate even left money to Lillian in her will.

Kate Gleason was an outstanding business woman whose career continued to blossom through the years as she pressed ahead in business endeavors which were traditionally male only. She never married or had children, but then it doesn’t sound like she was unfulfilled in her life’s work by not having a family of her own. A quote from Kate aptly sums up her business and personal philosophy: “I had been developing a talent that almost amounted to genius for putting myself in places where other women are not likely to come.”

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

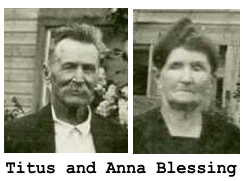

Tombstone Tuesday: Titus Walter Blessing – Medimont, Idaho

Titus Walter Blessing was born on August 4, 1855 in Dubuque, Iowa to parents Franz Joseph and Magdalena Rausch Blessing. His father, who went by his middle name Joseph, was born in Germany in 1826 and immigrated to America in 1850. His mother was born in Bavaria in 1825 and her date of immigration is unknown.

Titus Walter Blessing was born on August 4, 1855 in Dubuque, Iowa to parents Franz Joseph and Magdalena Rausch Blessing. His father, who went by his middle name Joseph, was born in Germany in 1826 and immigrated to America in 1850. His mother was born in Bavaria in 1825 and her date of immigration is unknown.

In 1860, Titus and his family were living in Porter, Freeborn, Minnesota, where his father was a farmer. In 1870, his family were still farmers and they had relocated to West Newton, Nicollet, Minnesota. Titus learned the mason trade and in 1876 he moved to Helena, Montana where he also mined and prospected across the state.

During the Indian Wars of the 1870’s, Titus fought Sitting Bull’s band of Indians and served as a private scout for Buffalo Bill, himself a scout for General Miles. When war broke out with the Nez Perce tribe, Titus joined eighty other citizens of Helena to fight, but the government wouldn’t allow them to fight unless they joined the military. They declined and returned home to Helena. Therefore, they apparently missed the Battle of Big Hole.

Titus met Anna Marguerite Hoffman, who had been born in Munster, Germany and immigrated to America in 1861, when she came from California to visit a cousin in Montana. On May 31, 1879 Titus married Anna and in 1880 they were enumerated in Helena, with Titus employed as a stone mason. Their first child, Amelia, had been born two months earlier.

Titus met Anna Marguerite Hoffman, who had been born in Munster, Germany and immigrated to America in 1861, when she came from California to visit a cousin in Montana. On May 31, 1879 Titus married Anna and in 1880 they were enumerated in Helena, with Titus employed as a stone mason. Their first child, Amelia, had been born two months earlier.

In 1881, another daughter, Anna, was born. In 1883 the family migrated across the Big Bend country to Spokane. Titus left his family there and went to Coeur d’Alene, arriving before the gold rush. He assisted in drafting a resolution barring Chinamen from coming into Coeur d’Alene County. It’s quite possible that Titus might have met Wyatt Earp who came to Idaho with his brother and common law wife Josephine Marcus for the Coeur d’Alene and Pritchard gold rush.

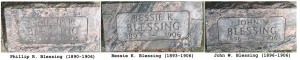

After mining for awhile, Titus sold his claims and became a rancher when the land previously occupied by the reservation opened up. There he built a homestead in Medimont, Idaho, and by 1900 Titus and his family had grown to include five more children: Rose Elizabeth (b. 1894), Walter Louis (b. 1888), Phillip Robert (b. 1890), Bessie Katie (b. 1893) and John Wesley (b. 1896). As of 1903, when a history of northern Idaho was compiled and published, Titus had one hundred and four acres of land and was doing well. Further, according to An Illustrated History of North Idaho: Embracing Nez Perces, Idaho, Latah, Kootenai and Shoshone Counties, State of Idaho:

Mr. Blessing has held the office of justice of the peace and is an excellent officer, being faithful and impartial. He has been active in the advancement of educational facilities and is a progressive man in all lines. He has some fine placer ground in the Saint Joe region and is developing it well. Mr. Blessing and his wife are true frontier people and have done a good work in development and building up the country.

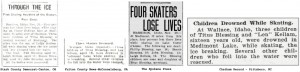

Tragedy struck the Blessing family in 1906, however. Interestingly, the story of their tragedy was found in newspapers across the country (perhaps taken from the wire service):

Titus and Anna’s three youngest children were skating on Lake Coeur d’Alene Lake on November 29, 1906. Other skaters were rescued but their children drowned along with another local resident. They were buried in the Medimont Cemetery in Kootenai County, Idaho.

Tragedy, unfortunately, struck again just three years later when their second daughter Anna died of an infection induced by surgical thread and scissors left in her body during surgery for cancer, according to family history. Anna was twenty-eight years old at the time of her death and was married to Eugene Leslie Lamb. Their son, Harvey Allen Lamb, had been born in 1906 and in 1910 Harvey (4 years old) was living with Titus and Anna in Medimont. His father remarried but it appears Harvey remained with his grandparents – he is again enumerated as their grandson in 1920.

Their daughter Rose, who had married John Ahlstrom, passed away in 1924 – like her sister Anna she died from complications following cancer surgery. She and her sister both were buried in the Medimont Cemetery with their younger siblings.

Titus continued to farm. At the age of seventy-four, he and Anna were enumerated in 1930 and living in Medimont. Their son Walter lived nearby and was employed as a farmer as well. On July 16, 1937, Titus Walter Blessing passed away at the age of eighty-one and was buried in the same cemetery as his children who had preceded him in death. His widow Anna and their son Walter would be buried in the same cemetery, Anna in 1940 and Walter in 1967.

Titus continued to farm. At the age of seventy-four, he and Anna were enumerated in 1930 and living in Medimont. Their son Walter lived nearby and was employed as a farmer as well. On July 16, 1937, Titus Walter Blessing passed away at the age of eighty-one and was buried in the same cemetery as his children who had preceded him in death. His widow Anna and their son Walter would be buried in the same cemetery, Anna in 1940 and Walter in 1967.

Titus Blessing was a pioneer settler of northern Idaho and highly esteemed by his fellow citizens:

A pioneer of the true grit and spirit, a man of sound principles and uprightness, a public minded citizen of worth and integrity, and always dominated with sagacity, keen foresight and manifesting energy and enterprise, the subject of this article is deserving of consideration in the history of this county.

A note of interest — the reader might notice links to previous articles I’ve written and published. I didn’t intend that there would so many links (Wyatt Earp, Josephine Marcus, The Battle of Big Hole) as Titus Blessing was, as is customary for the Tombstone Tuesday articles, picked randomly. I just love it when stuff like this happens though — and just another reason why I LOVE history and writing this blog!

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

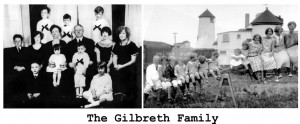

Mothers of Invention: Lillian Moller Gilbreth

Lillian Moller Gilbreth was born on May 24, 1878 in Oakland, California to parents William and Anne Moller. She grew up in a Victorian, German-American home, the second and oldest of ten children (the first child died in infancy). Lillie (she later changed her name to Lillian) was shy and introverted, so much so that she was schooled at home by her mother until the age of nine. Even then Lillian wasn’t able to “fit in” – academically she excelled but socially she was awkward. Home and domestic life were more suited to her, learning to sew and care for her siblings.

Lillian Moller Gilbreth was born on May 24, 1878 in Oakland, California to parents William and Anne Moller. She grew up in a Victorian, German-American home, the second and oldest of ten children (the first child died in infancy). Lillie (she later changed her name to Lillian) was shy and introverted, so much so that she was schooled at home by her mother until the age of nine. Even then Lillian wasn’t able to “fit in” – academically she excelled but socially she was awkward. Home and domestic life were more suited to her, learning to sew and care for her siblings.

By the time she entered high school she was actually eager to attend, although she still experienced social awkwardness with classmates. She dreaded the day when she would have to consider delving into the world of dating and courtship – she was petrified of boys and thought herself unattractive.

By the time she entered high school she was actually eager to attend, although she still experienced social awkwardness with classmates. She dreaded the day when she would have to consider delving into the world of dating and courtship – she was petrified of boys and thought herself unattractive.

While she resigned herself to perhaps remaining single, she yearned for something beyond remaining with her family to care for them and leading the life of a spinster. Writing, especially poetry, was a way for her to express herself, however. In the end, writing was what drew her out and she later found acceptance with her peers. One of her English teachers encouraged her to pursue a literary career. She admired her mother but she was inspired by her mother’s sister, Dr. Lillian Powers, a psychiatrist.

As the Victorian era came to a close in the late nineteenth century and the twentieth century dawned, there was a demographic shift in America from rural to urban – the country would soon become more mechanized. Social mores were changing as well. It became more acceptable for young ladies to pursue careers, although they weren’t welcomed as equals to their male counterparts in business and industry for years to come.

When she decided she wanted to pursue an academic career, her parents weren’t exactly thrilled, although they acquiesced when she rationalized to them that she would educate herself to become a teacher and to later care for her own children when she married. Deep down, however, Lillian hoped to avoid marriage and motherhood for awhile, if not altogether.

Lillian excelled at Berkeley, finishing at the top of her class with a degree in English. After graduating she wanted to continue her educational pursuits, but she wanted to attend school in the East, enrolling in Columbia’s Psychology Department. She had family in New York, but still her parents were concerned for her. She threw herself wholeheartedly into her studies, often skipping meals until she grew thin. When cold weather set in she became ill and had to return home to California.

Still determined to pursue a graduate education, she enrolled at Berkeley and planned to write a master’s thesis on Elizabethan literature. Having completed that degree, Lillian wanted to take a trip to Europe with friends before she began her doctoral program. Her parents would not allow here to travel un-chaperoned so one of the teachers at Oakland High School, Minnie Bunker, accompanied them. Before heading overseas, however, they made a stop in Boston to tour the city and meet Minnie’s family. There Lillian would meet her future husband, Frank Bunker Gilbreth, Minnie’s nephew.

Frank Gilbreth, being extremely gregarious and extroverted, was the polar opposite of Lillian, yet they later forged not only a strong and successful relationship as husband and wife, but as business partners. After their engagement, even before marriage, they forged a partnership. Frank was in the construction business and he relied on Lillian to edit manuscripts and prepare advertising materials. During their honeymoon trip, Frank requested of her a list of qualifications she was bringing to their “partnership”. However formal and rigid that might sound, the two made it work for years to come.

Frank Gilbreth, being extremely gregarious and extroverted, was the polar opposite of Lillian, yet they later forged not only a strong and successful relationship as husband and wife, but as business partners. After their engagement, even before marriage, they forged a partnership. Frank was in the construction business and he relied on Lillian to edit manuscripts and prepare advertising materials. During their honeymoon trip, Frank requested of her a list of qualifications she was bringing to their “partnership”. However formal and rigid that might sound, the two made it work for years to come.

Frank wanted to excel in the field of industrial management and motion study, and he spent a considerable amount of time away from home through the years of their marriage. He published several books and training materials over the year, under his name which were in actuality largely compiled and written by Lillian (while having babies, recovering from pregnancy and having yet another child soon after — thirteen in all, with eleven living to adulthood). In those times, of course, it wasn’t acceptable for women to receive recognition for achievements outside the societal norms of wife and mother.

Their business was successful, however, and Lillian added her own theories – she injected psychology, a human touch to the field of motion study and industrial management. Her profile would eventually be raised in that field, however, after Frank died suddenly in 1924, leaving her as the sole breadwinner for her large family. Although it was a struggle at times, Lillian Gilbreth more than arose to the occasion time and again over the remaining years of her long career.

When the Great Depression hit America, she was able to market herself effectively as she helped women stretch their money farther during that trying time. In 1926 she performed market research for Johnson & Johnson (sanitary napkins) and later helped improve management practices at Macy’s. She worked as an industrial engineer for General Electric, helping to re-invent and re-design the modern kitchen. Her work was thorough and meticulous as she interviewed over four thousand women to garner information regarding proper heights for stoves, sinks and other kitchen appliances and fixtures.

She designed an electric mixer, shelves for refrigerator doors and a trash can with a foot pedal and made “tweaks” and improvements on other appliances and devices. Amazingly, as skilled as she was with innovation in the kitchen, Lillian never learned to cook (for years her mother-in-law helped with household management). According to Lillian Gilbreth: Redefining Domesticity, “[P]rivately her children had referred to one of her culinary experiments as ‘Dog Vomit on toast’”.

She designed an electric mixer, shelves for refrigerator doors and a trash can with a foot pedal and made “tweaks” and improvements on other appliances and devices. Amazingly, as skilled as she was with innovation in the kitchen, Lillian never learned to cook (for years her mother-in-law helped with household management). According to Lillian Gilbreth: Redefining Domesticity, “[P]rivately her children had referred to one of her culinary experiments as ‘Dog Vomit on toast’”.

She was known as “Mother” for several things – “Mother of the Year” (1957), “Mother of Industrial Psychology” (1954), “Mother of Modern Management” and “the greatest woman engineer in the world” (1954). She received her doctoral degree before Frank passed away and later received over twenty honorary degrees and scores of awards for her work, even though she struggled early on to make a name for herself in the male-dominated field she chose to pursue.

Lillian raised successful children and worked tirelessly for years beyond the “normal” age of retirement. At the age of eighty-seven she was still traveling in both the United States and Europe to present lectures – even though her family encouraged her to slow down she continued to work. It was only after one of her children, Martha, died of cancer at the age of fifty-nine that her health began to decline. She moved in with one of her daughters in Arizona and later to a nursing facility. She died on January 2, 1972 at the age of 93.

In the book, Lillian Gilbreth: Redefining Domesticity, the author sums up her life this way:

Lillian Gilbreth never saw womanhood as biological destiny. As she modeled a strenuous life for her children, she proved that one could balance intellectual and family life, home and work, family and career on terms of ones choosing. She raised the status of homemakers by treating them as specialized experts of important work. But she also simplified housework enough to allow women to leave the home to achieve status and economic autonomy through other endeavors. If some of her idea seemed contradictory, she was proof of their liberating force.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Surname Saturday: Quackenbush

The Quackenbush surname has a unique distinction in American history. It is one of only a few surnames in North America which can be traced back to one single progenitor – Pieter van Quackenbosch. Records indicate that the name was primarily concentrated in a region of Holland (Leyden) and family genealogists have estimated that there were actually very few people with that name at any given point in time. One family researcher noted in The Quackenbush Family in Holland and America that the modern spelling (at least in the early 1900’s when the book was published) would be with “Kw” instead of “Qu” and even that spelling is unknown.

Records in Holland indicate that even though the family was few in number, they were established enough to serve in various civil offices. The “van” prefix didn’t necessarily imply any sort of rank as would the prefix “von” in Germany, perhaps just meaning “of” of “from”. “Quackenbosch” would be derived from “quakken”, or to croak like a frog and “bosch” would mean a bush or thicket. So perhaps the family lived in a wooded area near a pond where frogs were numerous and noisy.

The name had appeared as early as the fifteenth century and hadn’t varied one letter in spelling by the time the American progenitor immigrated in 1660, something quite unusual. Other spelling variations include: Quakenbaush, Quakenbush, Quakenbusc, Quackenbush, Quackinbush, Quackenbos, to name a few.

The name had appeared as early as the fifteenth century and hadn’t varied one letter in spelling by the time the American progenitor immigrated in 1660, something quite unusual. Other spelling variations include: Quakenbaush, Quakenbush, Quakenbusc, Quackenbush, Quackinbush, Quackenbos, to name a few.

Highlighted below are the American progenitor, Pieter van Quackenbosch and his family and a successful inventor and industrialist born in the nineteen century, Henry Marcus Quackenbush. The reference material for Pieter’s history is taken from The Quackenbush Family of Holland and America (QFHA).

Pieter van Quackenbosch

According to QFHA, Pieter van Quackenbosch was born in approximately 1639 and a resident of the village of Oegstgeest. At the age of twelve he enrolled first in Leiden University and then in Gronigen to study theology. However, he suddenly left in 1659, perhaps to join a group immigrating to the New World.

Since he came to North America with his wife and young son, presumably he had married while still in school. In 1660 at the age of twenty-one, Pieter arrived in New York (New Netherlands) and soon after his arrival he purchased property. This alone points to the fact that he was likely from a well-established family with a higher position in society than most immigrants (many came over as indentured servants, for instance).

Records indicate that he had intentions to settle somewhere other than Peter Stuyvesant’s colony. Since he eventually started a brick business, it’s possible he was looking for a more suitable location. Albany, or Beverwyck as it was called, would fit the bill since there was an abundance of clay in that region. The Dutch were well-known for their brick making, so it may have been the most natural occupation for him to pursue upon arrival in America, according to QFHA.

Accompanying Pieter to America were his wife Maritje, his young son Reynier and apparently his sister also named Maritje. His sister married Marten Cornelisse van Beuren, and interestingly, one of their descendants, Martin Van Buren was born in 1782 and in 1837 he became the eighth President of the United States. Not long after his arrival, another son was born. The children of Pieter and Maritje were:

Reynier

Johannes

Jannetje

Neeltje

Magdalena

Annetje

Wouter

Adriaan

Pieter

Classje

By 1668 Pieter had presumably prospered enough so that he was able to purchase the brick yard he had previously occupied (rented). His wife Maritje probably died in 1682 as records indicate he paid for the use of a large pall, a heavy cloth covering a coffin or tomb.

One of the oldest buildings in Albany today, the Quackenbush House, is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. It was built in the 1730’s by a descendant of Pieter. I found no more specific references to brick makers, although Pieter’s son Wouter probably inherited his father’s brick making business.

Colonel Hendrick (Henry) Quackenbush

The house was the home of Revolutionary War Colonel Hendrick (Henry) Quackenbosch, the son of Pieter Quackenbosch (Jr.). Henry was born in 1737 and died in 1813. The inscription on his grave marker read, in part:

Sacred to the memory of Col. Henry Quackenbush who having lived the life, died the death of the righteous. Col. Quackenbush was with Lord Amherst at Ticonderoga and General Gates at Saratoga. “In the days that tried mens souls”.

After the war, Henry had the distinction of being one of the presidential electors.

Henry Marcus Quackenbush

Henry Marcus Quackenbush was born on April 27, 1847 in Herkimer, New York to parents Isaac and Mary Anne (Rasbach) Quackenbush. Henry was said to have been mechanically-oriented, a tinkerer. At age fourteen he began an apprenticeship with Remington Arms where he became an expert metal worker and gun maker. On October 22, 1867, he received a patent for his first invention, the extension ladder and sold the patent for $500.

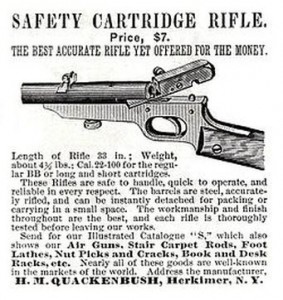

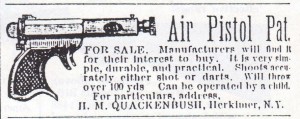

In 1871, the H.M. Quackenbush Company was founded in Herkimer. His first air gun pistol patent was issued on June 6, 1871. The patent was sold to the Pope Brothers of Boston who made and sold the gun. In 1876, the company began manufacturing air rifles. In the coming years the company would mass produce “gallery guns” for carnival and arcade shooting galleries.

However, guns weren’t the only thing Henry invented. Over the years he invented various kitchen gadgets (the Quackenbush Nutcracker), scroll saw, foot-powered wood lathe, darts, stair rails, bicycles and much more.

Henry Quackenbush married Emily Wood and they had two children together: Paul Henry and Amy. When Emily died in 1895 he married Flora Franks and they had two children: Franks and Henry Marcus, Jr., who was born in 1904 and died in 1910. Henry died at the age of 86 in 1933. His company was incorporated the year following his death and during World War II, the company manufactured military supplies such as bullet cores and shell casings.

In 1979 the company merged with Utica Plating Company and transferred the marketing and distribution of their products such as the nutcracker to another company. The downsized company experienced a gradual decline and in 2005 filed for bankruptcy and closed its doors.

There is a web site dedicated to “All Things Quackenbush” if you’re interested in knowing more about this family. You will find stories, news, blogs, photographs and much more about a proud American family, all of whom descended from Pieter van Quackenbosch.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Wild West Wednesday: Charles “Colorado Charlie” Utter

Charles H. Utter, a.k.a. “Colorado Charlie”, according to most sources was born around 1838 in New York state, near the Niagara Falls region. One individual in this past week’s Surname Saturday article, Abraham Utter, lived in New York state, so perhaps they were distantly related.

Charles H. Utter, a.k.a. “Colorado Charlie”, according to most sources was born around 1838 in New York state, near the Niagara Falls region. One individual in this past week’s Surname Saturday article, Abraham Utter, lived in New York state, so perhaps they were distantly related.

He is said to have grown up in Illinois and as a young man headed west, where he became a well- known guide, trapper and prospector in Colorado. In 1872 he was the guide who led a group of men and women up Gray’s Peak. A description of him was reported in the September 1872 Scribner’s Monthly:

Our guide is Charley Utter, who furnishes the twenty-eight saddle horses and the double wagon required by our somewhat numerous party. Dressed in his trapper-suit, Charley presents a figure well worth looking at. Buckskin coat and pantaloons–the latter ornamented with a leather fringe and two broad stripes of handsome bead-work; the former bordered with a similar fringe rimmed by a band of otter fur, and embroidered on the back and sleeves with many-colored beads, the handiwork of a Sioux squaw, and a wonderful specimen of Indian skill; vest of buckskin tanned with the hair on, and clasped with immense bear-claws instead of buttons; pistol, knife, and tomahawk in belt, the belt-buckle of Colorado silver and very large; a broad-brimmed hat and stout moccasins;–these are the externals of this famous Rocky mountain guide.

Said to be small in stature, he sported what many sources called a “dandified appearance” – extremely neat with long, flowing blond hair and a perfectly groomed moustache. One Colorado newspaper described him as a “courageous little man”. He wore handmade fringed buckskins, linen shirts and carried revolvers mounted in gold, silver and pearl. So fastidious was he about his appearance, he carried with him a mirror, combs and a whisk broom. While it was considered an oddity in the rough and tumble atmosphere of the mining camps, Charlie was said to have bathed each and every morning. According to one source, absolutely no one was allowed in his tent (not even his good friend James Butler, “Wild Bill” Hickok). Charlie met Wild Bill while working as a scout and hunter for the railroad in Kansas, according to one source.

Said to be small in stature, he sported what many sources called a “dandified appearance” – extremely neat with long, flowing blond hair and a perfectly groomed moustache. One Colorado newspaper described him as a “courageous little man”. He wore handmade fringed buckskins, linen shirts and carried revolvers mounted in gold, silver and pearl. So fastidious was he about his appearance, he carried with him a mirror, combs and a whisk broom. While it was considered an oddity in the rough and tumble atmosphere of the mining camps, Charlie was said to have bathed each and every morning. According to one source, absolutely no one was allowed in his tent (not even his good friend James Butler, “Wild Bill” Hickok). Charlie met Wild Bill while working as a scout and hunter for the railroad in Kansas, according to one source.

In 1866 he met and married fifteen-year old Matilda “Tilly” Nash, daughter of an Empire baker, in Colorado. In 1870, the census enumerated them in Georgetown, Clear Creek, Colorado Territory – he was 32 years old and she 19 years old. At that time, Charlie’s occupation was listed as “livery”, with the value of both real estate and personal property listed at $7,000 each. His brother Stephen was a miner and they worked together with mining agent William Bement. Charlie also ran a delivery service to the mining camps scattered around the Georgetown area.

In 1874, referring to the Black Hills gold rush, Charlie predicted a “lallapaloozer”. In the spring of 1876, he and Stephen, led a caravan of thirty wagon trains from Georgetown to South Dakota. One source reports that the caravan included prospectors, gamblers and 180 prostitutes. In Wyoming, Charlie met up with both Wild Bill and Calamity Jane who both joined his train and continued on with him to Deadwood. Some sources believe that Madame Moustache, known to be acquainted with Calamity Jane, also joined the caravan.

The caravan arrived in Deadwood in July of 1876. Soon after their arrival, Charlie established a livery and delivery service, and soon added an express mail service between Deadwood and Cheyenne, Wyoming – charging 25 cents per letter or parcel. It has been said that Utter was considered a protector of his friend Wild Bill, protecting Hickok from himself. Hickok was known to be both an excessive drinker and gambler.

On August 2, Charlie was away on a 48-hour mail run when his friend and “pard” Wild Bill was shot and killed by Jack McCall while playing cards in the Number 10 Saloon. Charlie returned to Deadwood to claim his friend’s body. He placed a notice in the Black Hills Pioneer:

On August 2, Charlie was away on a 48-hour mail run when his friend and “pard” Wild Bill was shot and killed by Jack McCall while playing cards in the Number 10 Saloon. Charlie returned to Deadwood to claim his friend’s body. He placed a notice in the Black Hills Pioneer:

Died in Deadwood, Black Hills, August 2, 1876, from the effects of a pistol shot, J. B. Hickok (Wild Bill) formerly of Cheyenne, Wyoming. Funeral services will be held at Charlie Utter’s Camp, on Thursday afternoon, August 3, 1876, at 3 o’clock, P. M. All are respectfully invited to attend.

Charlie sent a lock of Wild Bill’s hair to his wife, Agnes Lake. Wild Bill’s wooden grave marker read:

Wild Bill, J. B. Hickok killed by the assassin Jack McCall in Deadwood, Black Hills, August 2d, 1876. Pard, we will meet again in the happy hunting ground to part no more. Good bye, Colorado Charlie, C. H. Utter.

Scores of people came to pay their respects. Jack McCall’s trial was held at the same time as the funeral (justice was swift in those days!). Amazingly, McCall was found not guilty, but later it was discovered the trial was illegal. McCall was captured by U.S. marshals, retried and hung on March 1, 1877 in Yankton, South Dakota.

Charlie returned to Colorado the following year, but returned in 1879 to re-inter his friend’s body in the Mount Mariah Cemetery. Charlie remained in the Black Hills area and purchased the Eaves Saloon in Lead, another mining camp. He remained there for about a year, but was cited for operating without a proper liquor license. He returned to Deadwood only to lose everything in a devastating fire on September 26, 1879 which destroyed over three hundred buildings.

Charlie returned to Colorado the following year, but returned in 1879 to re-inter his friend’s body in the Mount Mariah Cemetery. Charlie remained in the Black Hills area and purchased the Eaves Saloon in Lead, another mining camp. He remained there for about a year, but was cited for operating without a proper liquor license. He returned to Deadwood only to lose everything in a devastating fire on September 26, 1879 which destroyed over three hundred buildings.

Again he returned to Colorado, and this time he was headed for Leadville in February of 1880. By June of that year he had moved on to Ruby City, Gunnison, Colorado where he was enumerated as a miner in the 1880 census. No mention of his wife, however (one source says that he and Tilly separated in 1880). He also spent time in Durango, Colorado and Socorro, New Mexico. In Socorro, he operated a saloon and gambling den (I wonder if he knew Syl Gamblin) and is thought to have married Minnie Fowler, a faro dealer. In 1884, he participated in Fourth of July festivities in Socorro, serving on the Grounds Committee, according to the Socorro Chieftain.

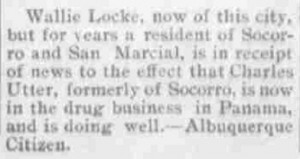

Sometime in 1888, Charlie was said to have left Socorro and went to Panama to operate a pharmacy, although historical records are hard to find. Some believe that he practiced medicine as well. A passenger list of the S.S. Turrialba notes that Charles H. Utter, druggist, sailed from Colon, Panama to New Orleans on July 21, 1910. The November 26, 1904 Socorro Chieftain verifies his residence in Panama:

Upton Lorentz, a druggist in Comfort, Texas related that the last time he saw his friend, Charlie was sitting “blind and grizzled” in front of his pharmacy in 1910. When and where Charles Utter died and was buried is unknown, however.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Tombstone Tuesday: Lieutenant Perrin Ross

Perrin Ross was born July 4, 1748 to parents Jeremiah and Anna Paine Ross in New London, Connecticut. Jeremiah Ross was one of the Connecticut settlers who helped form the Susquehanna Company in 1753. The Company acquired two thousand acres of land in the Wyoming Valley the following year, and the area would be disputed for several years between Connecticut and Pennsylvania. In 1773 Connecticut received permission from England to settle the area regardless of the dispute. Jeremiah migrated to the Wyoming Valley in 1774.

Perrin Ross was born July 4, 1748 to parents Jeremiah and Anna Paine Ross in New London, Connecticut. Jeremiah Ross was one of the Connecticut settlers who helped form the Susquehanna Company in 1753. The Company acquired two thousand acres of land in the Wyoming Valley the following year, and the area would be disputed for several years between Connecticut and Pennsylvania. In 1773 Connecticut received permission from England to settle the area regardless of the dispute. Jeremiah migrated to the Wyoming Valley in 1774.

Perrin married Mercy Otis, daughter of Joseph and Elizabeth Otis, date uncertain although some believe in 1768. Six children were born of their marriage: Jesse, Elizabeth, Joseph, John, Daniel, Perrin, Jr. (born after his father’s death).

Yesterday’s article on The Battle of Wyoming related the history of settlers from Connecticut populating the Wyoming Valley. Between 1769 and 1775 there were numerous clashes, an almost perpetual state of war. The conflicts were with both the Indians and Pennsylvanians who also laid claim to the area, and it’s likely that the Ross family experienced those dangers and participated in arming and defending the Valley.

Yesterday’s article on The Battle of Wyoming related the history of settlers from Connecticut populating the Wyoming Valley. Between 1769 and 1775 there were numerous clashes, an almost perpetual state of war. The conflicts were with both the Indians and Pennsylvanians who also laid claim to the area, and it’s likely that the Ross family experienced those dangers and participated in arming and defending the Valley.

On August 23, 1776, the Continental Congress established six companies to defend Pennsylvania. Two of those companies were stationed in the Wyoming Valley (Westmoreland). On August 26:

Congress proceeded to the election of sundry Officers, when Jonathan Dayton was elected Regimental Paymaster of Colonel Dayton’s Battalion; Robert Durkee and Samuel Ransom were elected Captains of the two Companies ordered to be raised in the Town of Westmoreland; James Wells and Perin Ross First Lieutenants; Ashbel Buck and Simon Spalding, Second Lieutenants, and Herman Swift and Matthew Hollomback Ensigns of the said Companies.

Some sources indicate that Perrin Ross and his companies had joined the Continental Army at some point and had fought in New Jersey. One record for application to the Iowa Sons of the Revolution, indicates that Perrin served with General Washington’s army beginning in January of 1777 and wintered at Valley Forge. According to The Massacre of Wyoming, The Acts of Congress for the Defense of the Wyoming Valley, Pennsylvania, Captain Ransom, Captain Durkee, Lieutenant Wells and Lieutenant Ross, all from the original companies formed in 1776, were home on furlough in July of 1778.