Feisty Female (or Not): The Legend of Hattie Cluck, Pioneer Woman

Today’s “Feisty Female” more than likely lived a fairly ordinary life. However, as time went on the stories of her exploits as the purported first woman to travel the Chisholm Trail, would make her an almost “larger than life” figure as a legendary Texas pioneer woman. Whether deserved or undeserved, Hattie Cluck nevertheless earned a special place in Texas history, feisty or not.

Today’s “Feisty Female” more than likely lived a fairly ordinary life. However, as time went on the stories of her exploits as the purported first woman to travel the Chisholm Trail, would make her an almost “larger than life” figure as a legendary Texas pioneer woman. Whether deserved or undeserved, Hattie Cluck nevertheless earned a special place in Texas history, feisty or not.

Harriet Louise Standefer was born on April 14, 1846 in Cherokee County, Alabama to parents James Stuart and Caroline (Randall) Standefer. Her paternal grandfather, Israel Standefer, had migrated to Texas in 1841, received a land grant in 1843 and represented Milam County at the Texas constitutional convention in 1845. Not long after Hattie’s birth the Standefer family made their way to Williamson County, Texas.

On October 8, 1849 Jimmie Standefer registered his cattle brand in Williamson County. By 1860 the family owned a large ranch where they raised cattle, corn and a few swine. Hattie began attending newly founded Salado College in Bell County that year. While attending a dance she met her future husband, George Washington Cluck. George was born in 1839 and came from a large family of eleven children (as did Hattie).

On October 8, 1849 Jimmie Standefer registered his cattle brand in Williamson County. By 1860 the family owned a large ranch where they raised cattle, corn and a few swine. Hattie began attending newly founded Salado College in Bell County that year. While attending a dance she met her future husband, George Washington Cluck. George was born in 1839 and came from a large family of eleven children (as did Hattie).

When the Civil War broke out, two of George’s brothers and at least one of Hattie’s brothers joined the Confederate Army. George, twenty-one years old when the war broke out, somehow avoided service in the war. On June 25, 1863 he and seventeen year-old Hattie were married. Before the end of the decade, George and Hattie were the parents of three children: Allie Annie (1864), George Emmett (1866) and Harriet Minnie (1869).

Before George met Hattie he had already established himself in the cattle business, registering his brand in Williamson County in November of 1859. The land around that area was free-range which meant there were very few, if any, costs associated with grazing or water. While there were nice profits to be made selling one’s cattle locally, those willing to herd the cattle farther away could make even more money.

In April of 1871 George and another rancher prepared to round up their cattle and drive them to Abilene, Kansas. Fourteen more men joined them, as did Hattie and their three young children, the oldest six and the youngest just over two. A trail drive could be treacherous and not considered a place where you would find a woman with young children, who was also pregnant with her fourth child. Years later she would remark that George “took all he had in the world with him, and we wanted to be together no matter what happened.”

Hattie’s granddaughter told a somewhat different story years later, indicating that it was Hattie who had been adamant about joining George on the trail. By all accounts, Hattie was not a physically imposing woman, but rather of slight and slender build. The granddaughter later remarked that never in her life did Hattie weigh more than one hundred pounds.

The cattle drive from Texas to Kansas was long and arduous, as one can imagine, and it appears that Hattie Cluck could have been the first woman to ever travel the Chisholm Trail. With her pregnancy and the care of her young children, she may not have contributed much along the way, but she did have some harrowing experiences. When they reached the Red River the water was flowing so swiftly that Hattie and the children had to cross on horseback rather than ride on the wagon. Instead, the wagons were floated across the river.

At one point they encountered a band of robbers. George and the other men gathered around Hattie’s wagon and prepared to confront the gang. The robbers demanded some of their cattle but George and his friends would defend their herd with guns if necessary. One legend says that Hattie helped the cowboys load their guns while others think that seems less likely. Nevertheless, the bandits rode away without any cattle.

They arrived in Abilene with a still-healthy herd and sold it. However, since Hattie was then closer to her due date they decided to wait for their fourth child, Euell Standefer Cluck, to be born on October 17, 1871. They remained in Kansas for a time and George engaged in various cattle transactions, which unfortunately also resulted in several lawsuits. Kansas farmers were hostile toward the Texas folks who drove cattle through their lands, damaging their crops.

That might have been the impetus for the Clucks to return to Texas. In October of 1873 George registered another cattle brand in Williamson County under Hattie’s name. In the ensuing years George made several good land deals and prospered in the cattle business. After a post office opened at Running Brushy, George donated money and land for a school. In 1874 Hattie became the postmistress until it closed in July of 1880.

When the railroads began laying track throughout the area, the Clucks made money after allowing the rail company water rights. With the railroad the new town of Cedar Park sprung up. During this period of time George and Hattie had six more children: Clarence Andy (1874), John Ollie (1876), Julie Maude (1878), David Albert (1881), Alvin Blain (1884) and Thomas Edison (1889). Hattie was forty-three years old when her last child was born. Her first child, Allie Annie, was twenty-five and had been married for eight years. George and Hattie later brought one more child into their family by informally adopting their nephew Joseph Matison Cluck, born in 1878.

HattieCluckFamilyGeorge died on August 23, 1920. According to Texas Women on the Cattle Trails:

Left a widow, Hattie Cluck lived quietly, making quilts, reading popular detective stories and Westerns, writing poetry, dreaming up plots for plays, and collecting Indian arrowheads, which she excavated from a productive site on her ranch less than two hundred yards from her home.

In 1930 Hattie was enumerated as the head of household whose occupation, at the age of eighty-three, was listed as “Run Farm”. Curiously, her son Tom lived with her and his occupation was “None”. That was also the year that the legend of Hattie Cluck was birthed. The founding of the Old Time Trail Drivers Association in 1915 had generated new interest in the history of trail drives. In 1930, and for the next several years, Hattie was interviewed for newspaper and magazine articles (and one book).

One of the first articles appeared in the April 20, 1930 issue of the Waco Sunday Tribune-Herald, in honor of Hattie’s eighty-fourth birthday. It seems, though, that the newspaper stretched their own journalistic credibility in reporting Hattie’s life history. The article included mention of her grandfather Israel, but also went on to report that at her birthday party she related stories about Indian warfare, saying: “She claims to have been the first white woman to go over the trail, made only three days behind Custer and his soldiers, who were massacred by Indians.”

Why the newspaper would attempt to associate her life experiences with Custer’s Last Stand (which, incidentally, occurred in 1876, five years after the trail drive) is unclear. The Austin American-Statesman seems to have strayed even farther from the truth: “Aged Central Texas Woman, Once a Fighter of Indians, Reads Tales of Adventure.” Again, according to Texas Women on the Cattle Trails, American-Statesman reporter Lorraine Barnes wrote:

. . . on their trail drive, the Clucks came across ashes that were “mute testimony” that, one day earlier, in what was “clearly a forerunner of the famous Custer massacre which took place a few years later,” Indians had attacked some travelers and burned a wagon. Barnes had been drawn to Hattie Cluck’s story by a recent celebration of her birthday and obviously interviewed Cluck. She more definitely stated that Cluck was “the first white woman to ride up the famous old Chisholm Trail” but indicated that Hattie was not entirely sure when the drive occurred. Cluck was pictured holding a nineteenth-century rifle. In Barnes’s account, when the Clucks were on the trail, they had a skirmish with a group of Indians. She attributed a quote to Hattie that describes her role in the skirmish: “I had to load the guns for the men and keep handing them out.”

In 1932 another reporter employed by the Austin American-Statesman, interviewed Hattie and toned down her story somewhat. In Irma Brown Cardiff’s account, Hattie told the story of the trail drive, but the bandits were white men, not Indians. There was no attempt this time, however, to link Hattie to Custer. Still, Hattie claimed to be the first white woman to travel the Chisholm Trail.

In 1935 a reporter published yet another article for the Farm and Ranch magazine, but unable to locate Hattie he used the 1932 Cardiff article as his source. Hattie had left Cedar Park and was then living with one of her children in Waco.

In 1936 two articles, both written by Thomas Ulvan Taylor, the dean of the engineering department at the University of Texas, were published. Taylor apparently fancied himself an historian. In his articles, one entitled “The Stork Rides the Chisholm Trail” and the other “The Stork Travels the Chisholm Trail”, Hattie’s story was again sensationalized:

In Taylor’s accounts, the Clucks encountered both white bandits and Indians. Hattie loaded guns for the cowboys, who were so “nervous and white under the gills” that she offered to stand and fight in their place if, as he had her say, “any of you boys are afraid to fight.” At the Red River, Hattie Cluck is similarly dauntless, planning the crossing for the timid men in the outfit. As one can tell by his titles, Taylor devoted considerable attention to Cluck’s pregnancy, which had not been mentioned by previous writers. (Texas Women on the Cattle Trails)

Taylor’s account seems to have cemented the legend of Hattie Cluck. On March 1, 1937, Hattie was interviewed by James Britton Buchanan Boone Cranfill, a leader in the Texas Baptist church and a vice presidential nominee for the Prohibition Party in 1892. Cranfill, a journalist, once again sought to rewrite history it seems. His piece was entitled “Mind My Babies and I’ll Fight These Rustlers; That’s Cry of Texas Woman on Chisholm Trail”:

Cranfill, who stated that Cluck was “the first Texas woman to ride up the trail,” described her as a bronco-busting crack shot, compared her courage to that of Joan of Arc, declared her to be intellectually brilliant, described her bearing and appearance as regal, and called her “the queen of the Chisholm Trail.” (Texas Women on the Cattle Trails)

In Cranfill’s account the Clucks’ encounter was with white men and not Indians, but Hattie’s story was again sensationalized when he had her holding a shotgun and George declaring her one of the best shots in Texas. Taylor had mentioned a fiddle in his story and Cranfill decided to embellish that reference for his piece. Cranfill claimed that one of the Cluck cowboys, an accomplished musician, was a man by the name of Buchanan Boone, which begs incredulity since that name just happened to be part of Cranfill’s own elongated name.

Hattie died in Waco at her daughter’s home on March 2, 1938, aged ninety-two. She was buried next to George in Williamson County in the Cedar Park Cemetery. While there was no mention in her obituary of the cattle drive and her purported exploits, her story was kept alive in the ensuing years. In 1989 a state historical marker was placed in the Cedar Park Cemetery. In 2003 the city of Round Rock dedicated a park to commemorate the spirit of the Chisholm Trail. A sculpture of Hattie Cluck was created and is located on the park grounds.

HattieCluckStatueI read various accounts of Hattie’s life before writing this article. The book which I used as source material, Texas Women on the Cattle Trail, was the only one that presented a detailed, yet balanced, view of Hattie Cluck’s history and written by Bill Stein. Stein’s chapter appears to have been thoroughly sourced, and therefore the most credible. As to the claim she was the first woman to travel the Chisholm Trail, Stein provided the following summary to close out his chapter for the book:

Whether she was the first white woman to go up the Chisholm Trail or not is of little consequence. If she was, as is certainly possible, it was mere happenstance. She made no conscious effort to overcome any perceived barriers, and nothing she did induced other women to follow her example. Except for her trip up the Chisholm Trail with a cattle drive, she led a conventional life. If she had not made that journey, other women certainly would have. However, before Hattie Cluck, it seems, no woman ever had.

Feisty female, legendary pioneer woman? You be the judge.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

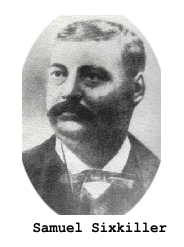

Wild West Wednesday: Samuel Sixkiller

Samuel Sixkiller was born circa 1842 in the Going Snake District (now Adair County, Oklahoma) of Indian Territory to parents Redbird and Permelia (Whaley) Sixkiller. Samuel was of mixed blood Cherokee heritage, his father being the son a half-breed Cherokee mother and a full-blood Cherokee father.

Samuel Sixkiller was born circa 1842 in the Going Snake District (now Adair County, Oklahoma) of Indian Territory to parents Redbird and Permelia (Whaley) Sixkiller. Samuel was of mixed blood Cherokee heritage, his father being the son a half-breed Cherokee mother and a full-blood Cherokee father.

As you might imagine, the Sixkiller surname is unique and believed to have its origins during a time when the Cherokee and Creek nations were at war. A man, possibly a great grandfather to Samuel, was said to have killed six men before being killed himself. He was thereafter called Sixkiller and the name was passed down to his descendants. Sam’s ancestors had been among those Native Americans removed from the southeastern part of the nation to reservations in the 1830’s.

As you might imagine, the Sixkiller surname is unique and believed to have its origins during a time when the Cherokee and Creek nations were at war. A man, possibly a great grandfather to Samuel, was said to have killed six men before being killed himself. He was thereafter called Sixkiller and the name was passed down to his descendants. Sam’s ancestors had been among those Native Americans removed from the southeastern part of the nation to reservations in the 1830’s.

Did you enjoy this article snippet? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. This article has been updated with new research and published in the January-February 2020 issue of the magazine. The magazine is on sale in the Digging History Magazine store and features these stories (140+ pages of stories, no ads):

This issue of Digging History Magazine is PACKED with stories! Generally, the main theme is the U.S. Census, but there are articles for both genealogists and history buffs to enjoy:

Since It’s a Census Year – What better way to launch 2020 than with an article on this important decennial event. You might be expecting a rather dry recitation of data gathered by the United States government, dating back to the first one conducted in 1790. You would be wrong! I’ve seen the data and accompanying documentation which the government used, and heaven knows only they must understand exactly what it meant!

Census data is vital to genealogical research, yet it’s more than just tick marks (up until the 1850 census), name, age, marital status, occupation and so on. There are literally thousands (more like MILLIONS) of stories to be gleaned – not that I will attempt that feat here, however. This extensive article will look at each decennial census beginning with the first in 1790, through the 1940 census.

Mining the 1880 Census Mother Lode – Family Search refers to the 1880 census as the “mother lode of questions pertaining to physical condition, criminal status, and poverty.” Talk about stories! It took the better part of the 1880s decade to process, but was it ever worth it, all courtesy of the “Supplemental Schedules for Defective, Dependent, and Delinquent Classes” (sometimes referred to simply as the “Defective Schedules”).

Up in Smoke: 1890 and Genealogy’s “Black Hole” (or is it?) – Put on your thinking caps. What event which took place ninety-nine years ago has since become an ever-present challenging obstacle to genealogists? On January 10, 1921 most of the 1890 census went up in smoke – “most” being the operative word. A March 1896 fire had already destroyed a number of these records.

Anyone who has been researching for any length of time likely realizes finding one’s ancestors involves trying many “keys” to unlock hidden caches of records, photos, and so on. Genealogists love census records because they are fairly easy to both access and assess, making the missing 1890 census a discouraging “black hole” for some who haven’t yet tried a little creativity. Why guess (or fudge) when you can do a little extra digging and maybe find a really interesting story! This article is filled with information about this genealogical “black hole” and how to find substitute records utilizing some “research adventure” stories.

The So-Called Calendar Riots and Modern-Day Genealogical Research – Most of us don’t think about time and its measurement in terms of historical context. It’s just time – something we never seem to have enough of in our “gotta-have-it-now” world. Twice each year our internal time clocks (for the majority of Americans) are re-set because we observe what is called “Daylight Savings Time”. We “lose” an hour of sleep in the Spring, only to “gain” it back in the Fall – “spring forward” and “fall back”. World travelers jet around the world every day, losing a day or gaining one by crossing the International Date Line.

We typically grumble about the loss of zzz’s but our bodies (eventually) adapt fairly well. We certainly aren’t particularly exercised over the loss are we? An hour here, or even a day, is not of much concern. But what if it were eleven days? In the mid-eighteenth century a stir rippled throughout England (although less so in its American colonies) as Parliament enacted calendar reforms in 1751. This calendar-altering event affects genealogical research to this day, yet not as dramatically as it seems to have stirred up the rural populace of England at the time – or perhaps we should say as much as political satirists of the time made of the change and (supposed) uproar.

It all seems to involve a bit of revisionist history. In 21st century vernacular let’s call it “fake news”. While researching this article which was to focus on the differences between the Julian and Gregorian calendar systems (sometimes called, respectively, “Old Style” and “New Style”) and how it affects genealogical research, I came across the phrase: “Give us our eleven days!”

Subsequent references to the phrase implied there had been “calendar riots” circa 1752 when England decided to join the rest of continental Europe and adopt the Gregorian calendar which had been around since the 1580s. Attempts to locate the phrase “give us our eleven days” or “give us back our eleven days” in the eighteenth century yielded a big goose egg, although simply using “eleven days” yielded a few references in both England and America around the time of the calendar shift. . . Plus, the story of “setting standard time” in the late nineteenth century (to avoid “fifty-three kinds of time”).

What in the Blue Blazes . . . happened to my ancestor’s (fill-in-the-blank) record? – Family Tree Magazine (May/June 2018) called them “Holes in History” – destructive fires throughout United States history with far-reaching effects on modern-day genealogical research. It might have been the deed to your third great-grandfather’s land in Mississippi, your grandfather’s World War II service record, or the missing 1890 census records. This article will take a look at the stories behind these devastating events and provide tips for finding substitutes.

Here’s something we can all agree on: nineteenth and early twentieth century courthouse fires are the bane of genealogists everywhere. Have you ever wondered why so many courthouse fires occurred in the latter half of the nineteenth century? Would it surprise you to find that many of them were set nefariously? (It shouldn’t.)

Getting Knocked Up (a Queer English Custom) – Once upon a time everyday working folks paid someone to “knock them up”. This, of course, elicits winks and giggles amongst 21st century denizens as “knocked up” often refers to what Merriam-Webster calls “sometimes vulgar: to make pregnant”. There was nothing vulgar intended or implied as this quaint and curious English and Irish custom, begun during the Industrial Revolution and carried forward into the early twentieth century (and beyond for some locales), was an honorable occupation. Before alarm clocks were available and affordable, “getting knocked up” was essential to ensure working men and women avoided fines for arriving late to work.

OK, I Give Up . . . What is It? (Did my ancestors ever violate intercourse(!) laws?) – First, I write an article about getting “knocked up” and now “intercourse laws”. Ahem. Lest anyone think I’m referring to the world’s oldest profession, let me explain. I run across many interesting phrases and curious terms while researching family history for my clients or research for the magazine. One phrase popped up recently and curiosity got the best of me (as it so often does!).

True Grit: Heck Thomas and Sam Sixkiller – This is a companion article to “Did my ancestors ever violate intercourse laws? The short answer — yes, if your ancestor lived near or among Indians they may have at one time or another “violated intercourse laws”. These two legendary “bad-ass” lawmen were kept plenty busy in Indian Territory back in the day.

Family History Tool Box, May I Recommend (Book Reviews) and more!

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Tombstone Tuesday: America Waldo Bogle

While researching this past weekend’s Surname Saturday article on the Waldo surname, I came across today’s subject. Her story is interesting and a bit intriguing, especially in regards to her parentage.

While researching this past weekend’s Surname Saturday article on the Waldo surname, I came across today’s subject. Her story is interesting and a bit intriguing, especially in regards to her parentage.

America Waldo was born on June 2, 1844 in Missouri. For years it was purported that Daniel Waldo was America’s father. However, it appears that couldn’t be true because Daniel and his family left for Oregon in 1843. His single brother Joseph, however, remained in Missouri (later going to Oregon in 1846). It seems more plausible that America was the child of Joseph Waldo and an unnamed slave. Also of note is the fact that the 1840 census indicates that Daniel did not possess slaves at that time, although his two brothers did.

America Waldo was born on June 2, 1844 in Missouri. For years it was purported that Daniel Waldo was America’s father. However, it appears that couldn’t be true because Daniel and his family left for Oregon in 1843. His single brother Joseph, however, remained in Missouri (later going to Oregon in 1846). It seems more plausible that America was the child of Joseph Waldo and an unnamed slave. Also of note is the fact that the 1840 census indicates that Daniel did not possess slaves at that time, although his two brothers did.

This article is no longer available for free at this site. It was re-written and enhanced, complete with footnotes and sources and has been published in the January-February 2019 issue of Digging History Magazine. Should you prefer to purchase the article only, contact me for more information.

This article is no longer available for free at this site. It was re-written and enhanced, complete with footnotes and sources and has been published in the January-February 2019 issue of Digging History Magazine. Should you prefer to purchase the article only, contact me for more information.

I invite you to check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? That’s easy if you have a minute or two. Here are the options (choose one):

- Scroll up to the upper right-hand corner of this page, provide your email to subscribe to the blog and a free issue will soon be on its way to your inbox.

- A free article index of issues is available in the magazine store, providing a brief synopsis of every article published in 2018. Note: You will have to create an account to obtain the free index (don’t worry — it’s easy!).

- Contact me directly and request either a free issue and/or the free article index. Happy to provide!

Thanks for stopping by!

Surname Saturday: Waldo

There are two theories as to the origins of the Waldo surname. One source believes the surname is Low German, the name having first been seen there in the thirteenth century along the Franconian-Bavarian border. It is believed that the name is one of the oldest in Germany and also belongs to some of the wealthiest landowners of that time. The family’s ancestral castle was named Waldau. Spelling variations for this surname of Germanic origins include Waldau, Waldauer, Waldov, Waldow, Zumwalt and others.

The second theory points to a baptismal name which meant “son of Walter” and derived from the Old Norman name “Valporfr”. Early records list someone (without surname) in the Domesday Book of 1086 as “Walteif.” Later Adam Walthef was recorded in Yorkshire in 1219 and Thomas de Walthe was recorded in Sussex in the next century. Spelling variations include Walthew, Waldie, Walde, Watthey, Waddy, Wealthy and Wilthew.

Peter Waldo

One of the early historic figures bearing this surname was Peter Waldo, a merchant who later became a minister in Lyon (France). The Christian sect he founded, the “Waldensians”, adhered to a strict interpretation of scriptures as well as advocating voluntary poverty.

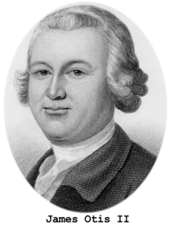

Another minister made his mark on American history after living to be one of only six remaining Revolutionary War veterans to be interviewed and photographed for a history book published in 1864, entitled The Last Men of the Revolution.

Daniel Waldo

Daniel Waldo was born on September 10, 1762 in Windham, Connecticut to parents Zacheus and Tabitha (Kingsbury) Waldo. He was the ninth of thirteen children. His great-great grandfather, Deacon Cornelius Waldo, was one of the earliest Waldos to arrive in America, landing at Ipswich, Massachusetts in 1654. Daniel’s great-grandmother was an Adams with direct ties to the family of Presidents John and John Quincy Adams.

Daniel Waldo was born on September 10, 1762 in Windham, Connecticut to parents Zacheus and Tabitha (Kingsbury) Waldo. He was the ninth of thirteen children. His great-great grandfather, Deacon Cornelius Waldo, was one of the earliest Waldos to arrive in America, landing at Ipswich, Massachusetts in 1654. Daniel’s great-grandmother was an Adams with direct ties to the family of Presidents John and John Quincy Adams.

In 1778, at the age of sixteen, Daniel joined the Continental Army. The following year he was taken prisoner by the Tories in Horseneck, Connecticut. He was later taken to New York along with other members of him company. There they were imprisoned in Sugar House, a sugar refinery, but released in a prisoner exchange two months later.

Around the age of twenty Daniel became a Christian and decided to devote his life to ministry. He enrolled at Yale University and graduated in 1788 with an M.A. in theology. He was licensed to preach the following year on October 13, 1789 and on May 24, 1792 was ordained. He married Nancy Hanchett and together they had five children. However, in 1805 she became insane but lived until 1855. Daniel would later remark, “I lived fifty years with a crazy wife.”

He continued serving as both a minster and missionary and in 1856, at the age of ninety-four, was appointed as Chaplain of the House of Representatives. During his tenure he officiated at the funeral of Preston Brooks who famously assaulted fellow representative Charles Sumner on the House floor over the issue of whether Kansas would be admitted as slave or free state (click here to read an article addressing the controversy). During his tenure with Congress, Daniel Waldo spent a lot of time reading, and was heard to say of congressional proceedings that he didn’t wish to hear “the quarrels in the House.”

He continued serving as both a minster and missionary and in 1856, at the age of ninety-four, was appointed as Chaplain of the House of Representatives. During his tenure he officiated at the funeral of Preston Brooks who famously assaulted fellow representative Charles Sumner on the House floor over the issue of whether Kansas would be admitted as slave or free state (click here to read an article addressing the controversy). During his tenure with Congress, Daniel Waldo spent a lot of time reading, and was heard to say of congressional proceedings that he didn’t wish to hear “the quarrels in the House.”

Although he believed that the Union Army would prevail in the Civil War and he deemed President Lincoln an honest man, though not decisive enough, “he thought that the leaders of the rebellion should be dealt with in such a manner that no one would dare, in the future, to repeat the experiment.” In his closing years, Daniel lived with his eldest son while still serving as the House Chaplain. After falling down a flight of stairs, Daniel Waldo died on July 30, 1864, just a few weeks short of his 102nd birthday.

Another minister, Elias Hillard, had earlier set out to locate the last six surviving veterans of the Revolutionary War, all of them over the age of one hundred. The nation was still fighting the Civil War, but Hillard was determined to interview the six veterans and photograph them. At the time, Hillard remarked, “our own are the last eyes that will look on men who looked on Washington; our ears the last that will hear the living voices of those who heard his words.” Daniel Waldo was one of the six remaining veterans, although he never met or saw George Washington in person.

Hillard wrote of Daniel’s philosophy of life, perhaps his secret to longevity:

Hillard wrote of Daniel’s philosophy of life, perhaps his secret to longevity:

In his personal habits, Mr. Waldo was very careful and regular. His standing advice was to “eat little.” He drank tea and coffee. The control of the temper he deemed one of the most important conditions of health, declaring that a fit of passion does more to break down the constitution than a fever. His mental vigor he retained wonderfully to the last. His memory was excellent, differing from that of most aged people, in that he retained current events with the same clearness as the earlier incidents of his history.

To close his sketch of Daniel Waldo, Elias Hillard quoted a friend of Daniel’s:

Mr. Waldo possessed naturally a clear, sound, well balanced mind, with little of the metaphysical or the imaginative. He was a great reader, eagerly devouring every work of interest that came within his reach. His spirit was eminently kind and genial, and this, united with his keen wit and large stores of general knowledge, made him a most agreeable companion.

He was one of the most contented of mortals. Though he experienced many severe afflictions, and had always from an early period of his ministry one of the heaviest burdens of domestic sorrow resting upon him, his calm confidence in God never forsook him, nor was he ever heard to utter a murmuring word. As a preacher, he was luminous, direct, and eminently practical; his manner was simple and earnest, and well fitted to command attention. At the close of a life of more than a hundred years, there is no passage in his history which those who loved him would wish to have erased.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Feisty Females: Mercy Otis Warren

Tomorrow marks the 226th anniversary of the United States Constitution’s ratification when New Hampshire became the ninth state to approve. In honor of that occasion, today’s “feisty female” is a woman whose writings no doubt helped shape that historic document. Her activism both before and during the Revolutionary War served to rally the cause for liberty from British tyranny.

Tomorrow marks the 226th anniversary of the United States Constitution’s ratification when New Hampshire became the ninth state to approve. In honor of that occasion, today’s “feisty female” is a woman whose writings no doubt helped shape that historic document. Her activism both before and during the Revolutionary War served to rally the cause for liberty from British tyranny.

Mercy Otis was born on September 14, 1728 in West Barnstable (Cape Cod) to parents James and Mary (neè Allyne) Otis. Her father was an industrious and prosperous merchant, attorney and judge who fared well enough to send his sons to Harvard. While education was neither encouraged nor mandated in that day for girls, Mercy managed to receive an informal education, by accompanying her brothers who were tutored by their uncle Reverend Jonathan Russell. She was allowed to study side-by-side with her brothers all subjects except Latin and Greek.

Mercy Otis was born on September 14, 1728 in West Barnstable (Cape Cod) to parents James and Mary (neè Allyne) Otis. Her father was an industrious and prosperous merchant, attorney and judge who fared well enough to send his sons to Harvard. While education was neither encouraged nor mandated in that day for girls, Mercy managed to receive an informal education, by accompanying her brothers who were tutored by their uncle Reverend Jonathan Russell. She was allowed to study side-by-side with her brothers all subjects except Latin and Greek.

In many ways the path that Mercy chose was an unusual one for a young woman of that day. Her education broadened her horizons beyond that of the normally expected role of wife and mother (she didn’t marry until her mid-twenties). She possessed a quick-wit and enjoyed freewheeling political discussions with her father and brothers.

In 1754 she married James Warren and moved to Plymouth. James and Mercy had five sons: James (1757), Winslow (1759), Charles (1762), Henry (1764) and George (1766). While embracing a traditional role of wife and mother, Mercy continued to further her education as an avid reader of literature.

James Warren became involved in politics after being elected to the Massachusetts House of Representatives, later serving as the Speaker of the House and President of the Massachusetts Provincial Congress. Mercy supported her husband throughout his political career, becoming more active in civic and political affairs as acts of British tyranny increased. Their home was a meeting place for those of like-minded beliefs to gather and debate. At some point the Warrens made the acquaintance of John and Abigail Adams, and thereafter Mercy corresponded regularly with them. Although Mercy was sixteen years older than Abigail, the two became close friends and confidants.

James Warren became involved in politics after being elected to the Massachusetts House of Representatives, later serving as the Speaker of the House and President of the Massachusetts Provincial Congress. Mercy supported her husband throughout his political career, becoming more active in civic and political affairs as acts of British tyranny increased. Their home was a meeting place for those of like-minded beliefs to gather and debate. At some point the Warrens made the acquaintance of John and Abigail Adams, and thereafter Mercy corresponded regularly with them. Although Mercy was sixteen years older than Abigail, the two became close friends and confidants.

When Mercy began writing and publishing around 1772, she did so anonymously. She wrote plays and published propaganda-type articles in the newspapers – her husband referred to her as a “scribbler.” The colonists were establishing de facto “shadow governments” called “Committees of Correspondence.” In November of 1772 the Massachusetts Committee of Correspondence was formed in the Warren’s home by Samuel Adams and Joseph Warren. Years later Mercy wrote that these committees were so effective that “no single step contributed so much to cement the union of the colonies.”

The only play she wrote under her own name was The Group, a satire about what would happen if the King took away Massachusetts’ charter of rights. Mercy wasn’t the only member of her family to engage in political activism. Her brother James adamantly opposed British policies and coined the phrase “taxation without representation is tyranny.”

His activism put him in danger – he was attacked and severely beaten in a Boston coffee house in 1769. He never recovered from the brain injuries, slowly slipping into insanity. While under the care of his sister Mercy in 1775, and after hearing of the Battles of Lexington and Concord, he ran away and joined the militia to fight in the Battle of Bunker Hill. After the war, he moved to Andover and died in 1783 after being struck by lightning.

His activism put him in danger – he was attacked and severely beaten in a Boston coffee house in 1769. He never recovered from the brain injuries, slowly slipping into insanity. While under the care of his sister Mercy in 1775, and after hearing of the Battles of Lexington and Concord, he ran away and joined the militia to fight in the Battle of Bunker Hill. After the war, he moved to Andover and died in 1783 after being struck by lightning.

James Warren was appointed as a Major General in 1776 and also served as the Paymaster General of the Continental Army from 1776 to 1781. In his absence, Mercy was in charge of family affairs back in Plymouth, where she continued to write in support of the revolution. After the war, however, Mercy and James Warren fell out of favor with their friends John and Samuel Adams. As the new government was being formed following the war, Mercy argued against the federalists in favor of self-rule.

In 1788 she published a pamphlet entitled Observations on the New Constitution which expressed her strong anti-federalist (opposed to a central government) beliefs. Although unsuccessful in preventing the ratification of the Constitution, some historians believe the pamphlet may have influenced the later inclusion of the Bill of Rights which were adopted in 1789.

In 1805 Mercy published a three-volume book entitled History of the Rise, Progress and Termination of the American Revolution. Her work is set apart as one of the most knowledgeable and comprehensive histories written about the Revolutionary War, and the only written by a woman. The book was prefaced by her still-strong patriotic sentiments: “every domestic enjoyment depends on the unimpaired possession of civil and religious liberty.” The book further widened the schism in her relationship with John Adams, resulting in heated correspondence going back and forth until 1812. Adams believed he had been slighted and passed it off with a remark aimed at his antagonist: “history is not the Providence of Ladies.”

After returning from the war, James Warren, having fallen out of favor with leaders who were forming the new government, was prevented from holding office again. He died on November 28, 1808. On October 19, 1814, Mercy Otis Warren died at the age of eighty-six. She is buried at Burial Hill in Plymouth. Her activism in support of liberty earned her a place in the National Women’s Hall of Fame, as well as a World War II liberty ship named in her honor, the SS Mercy Warren.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

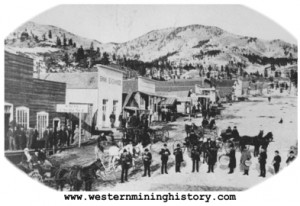

Ghost Town Wednesday: Maiden, Montana

In 1880 five prospectors, “Skookum Joe” Anderson, c.c. Snow, Eugene Ervin, Pony McPartland, and David Jones, discovered gold in the Judith Mountains near Lewiston, Montana. There are at least two theories as to how the mining town they founded got its name. One story says that one of the early prospectors was named Maden and put up a sign calling the location “Camp Maden” – and later an “i” was added to make it Maiden. Another theory is that the town was named after a friend’s daughter who was referred to as “Little Maiden.”

In 1880 five prospectors, “Skookum Joe” Anderson, c.c. Snow, Eugene Ervin, Pony McPartland, and David Jones, discovered gold in the Judith Mountains near Lewiston, Montana. There are at least two theories as to how the mining town they founded got its name. One story says that one of the early prospectors was named Maden and put up a sign calling the location “Camp Maden” – and later an “i” was added to make it Maiden. Another theory is that the town was named after a friend’s daughter who was referred to as “Little Maiden.”

Speaking of naming, here are some of the names attached to mines in the area: Tom Thumb, War Eagle, Sun Dance, Yankee Blade, Little Rhoda, Jessie Trim, Maginnis, Collar, Kentucky, Maggie C. Weeden, Pilgrim, Hailstorm, Lone Star, Sucker State, Spotted Horse, Bamboo Chief, Crow Girl, Niagra, Treasure Box, Wolverine and many others. Unique names with equally unique histories I’m sure.

Speaking of naming, here are some of the names attached to mines in the area: Tom Thumb, War Eagle, Sun Dance, Yankee Blade, Little Rhoda, Jessie Trim, Maginnis, Collar, Kentucky, Maggie C. Weeden, Pilgrim, Hailstorm, Lone Star, Sucker State, Spotted Horse, Bamboo Chief, Crow Girl, Niagra, Treasure Box, Wolverine and many others. Unique names with equally unique histories I’m sure.

The Spotted Horse mine was by far the most productive mine, operating from 1881 until 1902 it yielded in excess of five million dollars in gold, with the largest yields coming during the early years when high-grade ore was being extracted. The Maginnis mine was opened in 1880 and worked at various intervals until 1899, and finally closed in 1909. Over the years Maginnis produced almost two million dollars in gold.

The town site was established in 1881, although neither platted nor surveyed. Instead lots were designated by selecting one and building a fence around it. News spread quickly and soon the town was booming. By 1882 there were several businesses, including saloons, clothing stores, general merchandise and dry-goods stores, a blacksmith, barbers, one law and one doctor’s office, hotel and restaurant. Obviously, cash was flowing from the influx of both independent prospectors and capitalists.

The town site was established in 1881, although neither platted nor surveyed. Instead lots were designated by selecting one and building a fence around it. News spread quickly and soon the town was booming. By 1882 there were several businesses, including saloons, clothing stores, general merchandise and dry-goods stores, a blacksmith, barbers, one law and one doctor’s office, hotel and restaurant. Obviously, cash was flowing from the influx of both independent prospectors and capitalists.

After capitalists began to enter the mining district, existing mines began to be extensively worked and mills were built to process the ore. Investors poured thousands of dollars into the Collar Company Mine to ascertain the possible yields. Unexpectedly, the mine closed in late 1883 after only a nine-day run. As it turned out, the collapse of the Collar Company was due to corporate mismanagement. The value of the mine had been overestimated and when expenses were more than expected, investors balked.

The failure of the mine was devastating to the town, since the company was basically bankrupt. That meant that employees wouldn’t be paid until a sale could be arranged. Another threat to the town’s prosperity had occurred earlier in 1883 when nearby Fort Maginnis (the town was situated within the fort’s reservation) posted an order requiring all residents to vacate Maiden. Protests were lodged and the army decided to instead reduce the size of the reservation to exclude Maiden and the surrounding mines.

In June of 1884 investors formed the Maginnis Company. With new infusions of investment cash, mining picked back up and miners were put back to work, a boon to the town of Maiden. Not only was commerce booming but culturally the town had a brass and coronet band, as well as an amateur baseball team. Maiden would also become a stop for two stage routes.

In 1885 the new county of Fergus was created and Maiden vied for the honor of being the county seat, up against the cattle town of Lewiston. The rivalry brought boasts from both sides, but in the end Lewiston won the seat in 1886, with mining taking a back seat to the cattle and sheep industries. Even with the appearance of prosperity, the town of Maiden would continue to struggle as the realities of mining in a remote location began to sink in.

There were water shortages which forced the company to build a reservoir. Another complication was the remoteness of the area. Freight delivery was expensive with steeply-graded trails which were best traveled during the dry season. Over the next several years, the fortunes and misfortunes of mining operations would vacillate – some years better than others. After a time the higher-grade ore played out and with marginal qualities of ore being extracted in the mid-1890’s, the population began to dwindle.

In 1896 there were less than two hundred residents and many of the mines had closed. By the early 1900’s, towns like Lewiston prospered and grew while the mining towns were languishing. In 1905, a fire destroyed most of Maiden. With no interest in rebuilding, Maiden became a ghost town.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Mining History Monday: Vermilion Lake Gold Rush

During the nineteenth century thousands of people headed west to find their fortunes, but in 1865 gold was discovered in an unexpected place – in northern Minnesota, just south of the Canadian border. The discovery was more or less accidental since the original survey commissioned by Minnesota Governor Stephen Miller was meant to locate iron ore deposits.

During the nineteenth century thousands of people headed west to find their fortunes, but in 1865 gold was discovered in an unexpected place – in northern Minnesota, just south of the Canadian border. The discovery was more or less accidental since the original survey commissioned by Minnesota Governor Stephen Miller was meant to locate iron ore deposits.

In 1864 Miller sent Augustus Hanchett to the Lake Vermilion area of northern Minnesota “for the purpose of determining the existence, character and extent of the iron depots in that vicinity.” Hanchett began his survey in late September and soon confirmed the existence of deposits, but had little time to fully determine the quantities before winter set in.

The following year Governor Miller asked the legislature to fund a complete survey led by Henry Eames. Eames and his surveyors departed from Duluth in the spring and began to extensively survey Hanchett’s findings. Eames did indeed find iron ore and confirmed its presence but didn’t forward samples to the governor. Instead, Eames and his brother brought home samples containing quartz and then forwarded them to New York City for a chemical analysis. To ensure he would be the first to know the results of the analysis Eames ordered them sent to his attention. Not surprisingly, after receiving favorable results, Eames was eager to stake his claim.

The following year Governor Miller asked the legislature to fund a complete survey led by Henry Eames. Eames and his surveyors departed from Duluth in the spring and began to extensively survey Hanchett’s findings. Eames did indeed find iron ore and confirmed its presence but didn’t forward samples to the governor. Instead, Eames and his brother brought home samples containing quartz and then forwarded them to New York City for a chemical analysis. To ensure he would be the first to know the results of the analysis Eames ordered them sent to his attention. Not surprisingly, after receiving favorable results, Eames was eager to stake his claim.

Eames then forwarded samples of iron ore and quartz to the governor who ordered his own analysis. The findings were promising – the proportion of gold per ton was $25.63 and silver at $4.42 per ton. Governor Miller, like Eames, wanted the results telegraphed directly to him so that he would have personal knowledge before the general public. Thus, at least a week before the results were made public in the newspapers, he had already positioned himself to profit from the Lake Vermilion discovery.

In an article written for the Minnesota Humanities Commission, The Vermilion Lake Gold Rush, 1865-1866, Dana Miller observed that, of course, today such behavior would be unethical and illegal. However, the “gilded age” had begun, the period of time from 1865 to 1901 which was so-coined by Mark Twain. As Miller pointed out, these were perfectly acceptable practices and even thought to be “good business sense.”

The discovery of gold in those days caused waves of excitement no matter where it had been found. Before long newspapers across the country were reporting the news:

Even though the original estimates were less than thirty dollars per ton, speculations were already circulating as to the potential of fifty to sixty dollars per ton (without any apparent data to back it up). Daily news stories drove fortune hunters to Lake Vermilion, this despite the fact that the process of extracting the gold would be more difficult than that found in the West – some of the fortune-seekers even came from as far away as California. While there were plenty of individual miners, there were a number of small groups and corporations who wanted to invest time and money at Lake Vermilion.

One company of twenty-five men each contributed $150 and formed the “Mutual Protection Gold Miner’s Company” (later adding twelve more partners). Thomas McLean Newson was the company’s president and founder. The “Mutuals” (as they called themselves) planned to travel to Vermilion to search for gold, but they also had plans to live there and “civilize” the place. Many of them were Civil War veterans who had muster pay to fund their venture. Newson, who served as a Major in the war, ran operations much like the military with an ordered chain of command.

One company of twenty-five men each contributed $150 and formed the “Mutual Protection Gold Miner’s Company” (later adding twelve more partners). Thomas McLean Newson was the company’s president and founder. The “Mutuals” (as they called themselves) planned to travel to Vermilion to search for gold, but they also had plans to live there and “civilize” the place. Many of them were Civil War veterans who had muster pay to fund their venture. Newson, who served as a Major in the war, ran operations much like the military with an ordered chain of command.

One wonders now if these men really knew what they were getting into, for they departed on December 26, 1865, in the dead of winter. The group encountered dense forests with only a wilderness trail, deep snow drifts and temperatures well below zero. But the Mutuals, especially Newson, were so sure they would be successful that they pressed on and arrived on March 6, 1866. Newson summed up their journey for the St. Paul Pioneer:

The work of cutting a road was one of greater magnitude than the reader will imagine. Nearly the whole force of the Mutuals were engaged in it, and day after day from dawn to dark, slashed away at the big trees in their road, scarcely any of them less than a foot thick. Of course slow progress was made, and many discouragements met with, but they pressed on perseveringly and undaunted, and finally reached the end of their route safe and sound . . . No accidents happened to any of them on the entire trip; and every man was tougher, fitter and heavier than he had ever been before.

While waiting for the spring thaw, the Mutuals began planning their town. By April, Winston City had about three hundred men, two stores, several houses, a city hall which doubled as the company’s headquarters, and several saloons. The Mutuals weren’t the first to arrive, and their presence and persistence in quickly establishing their city was met with some opposition. One of their opponents referred to Newson as “Generalissimo High Cochilorun Chief”.

Gold discoveries often brought out the worst in people, however, and it became necessary to set rules of conduct. As the weather changed and became more spring-like, the winter snows melted, which in turn brought muddy, swampy conditions and mosquitoes. Those conditions also made it especially difficult for supplies to be transported to the area.

By summer there were as many as five hundred men in the area and miners were working all around the area. It appears, though, that the work proved to be more difficult than most imagined. A full day’s sweat and toil may only have yielded precious few inches toward their goal. Even with less than encouraging results, the Mutuals continued to issue optimistic reports. However, as winter approached the realities of facing a harsh winter in such a remote location without tangible results caused many of the Mutuals to abandon the project and return home.

When the next spring arrived, some prospectors returned, although not in the numbers seen in 1866. It wasn’t even news any longer as newspapers had very little to say about the Vermilion “gold rush.” By 1868, what “rush” there had been was over.

Afterwards, critics claimed there never was any gold at Lake Vermilion, although Henry Eames had been so sure that gold did indeed exist there. Since early on he sought to profit from the government-funded survey, perhaps greed was part of the problem. After all, the original purpose of the survey had been to approximate the iron ore potential of the area, not the discovery of gold or other precious minerals. Their hopes and desires for fortune were likely influenced by the wildly successful gold rushes out West. However, prospecting gold in California with a pan down by the river was infinitely less physical work than what miners encountered at Vermilion.

Later, iron ore would indeed be discovered, as it turned out, by miners on their way to find gold.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Surname Saturday: Keep

Like many surnames of Early or Middle English origin, the spelling of the Keep surname evolved over time. These names were recorded, beginning in the fourteenth century:

Walter Kep (1230)

John Kepe (1290)

William atte Kep (1290)

Thomas ate Kepe (1327)

Robert de Keepe (1332)

William Keppe (1583)

Henry de Keepe (1611)

Mary Keep (1681)

One family historian discovered that during the eleventh century (before William the Conqueror’s invasion), the name was spelled “Cheppe”.

It is possible the name was either residential or occupational. If residential it might describe a person who lived at a castle (de Keep), or if occupational it may refer to someone who was a jailer. In Middle English the word “keep” derived from the verb “keepen,” meaning to hold or defend.

Keep family historians believe that John Keep of Longmeadow, Massachusetts was the progenitor of all Keeps in America, although the date of his arrival is unknown. With the advent of DNA testing, a link has been established to link John Keep with an early ancestor, Walter Kep (1230), he of the East Midland Keeps (Bedfordshire, Northamptonshire and Birmingham).

John Keep

The birth date of John Keep, as well as his arrival in New England, is unknown. The Great Migration of those fleeing religious persecution began in 1620 and continued through the early 1640’s. If John was indeed one of the early immigrants, wherever he landed he would have been faced with the dangers and challenges which all Pilgrims encountered, of which there are extensive historical records.

What is known is that at some point, perhaps in 1660 or just before, John moved inland to the town of Springfield. On February 18, 1660 it was recorded in town records: “John Keepe desiring entertaynmt in this Towne as an Inhabitant his desires were granted by the Select men ye day above said.” Springfield was a closed settlement and at that meeting John had been granted residence.

Less than a month later on March 13, John was granted five acres of meadow land, and over the ensuing years records indicate he acquired more. It is also evident from town records, that John Keep was a prominent citizen and held various offices in his community. On February 11, 1666 it was noted:

There was choise made of veuars of fences for the severall ffields. John Keepe and Samuel bliss veiwers for the long medo and the Home Lotts as far as the meeting house.

A fence viewer had authority to administer fence laws and would have inspected new fence and helped to settle disputes such as livestock trespassing on a neighbor’s land. He later was appointed to the office of surveyor and court records indicate he served as a juror at various times. Thus, he was obviously a prominent member of the town and considered to have good judgment.

On December 31, 1663, John married Sarah Leonard and to their marriage were born:

Sarah (1666)

Elizabeth (1668, died in 1675)

Samuel (1670)

Hannah (1673)

Jabez (1675, killed by Indians in 1676)

In 1676 youngest son Jabez, along with John and Sarah, met their untimely deaths. After Massasoit had died and his successor son Wamsutta also died, Philip became the leader of the Pokanokets. While his father had gotten along reasonably well with the colonists, Philip had a distrust and hatred of the colonists (his brother Wamsutta had died in their custody). In June of 1675 King Philip’s War began with an attack on the Plymouth colony of Swansea, killing ten colonists.

In October Springfield was attacked and several houses and barns were burned, but Longmeadow was spared. The English retaliated on December 19 by attacking an Indian winter camp where several hundred Indian women, children and elderly were burned to death. The dangers were so great during the winter of 1675-1676 that residents of Longmeadow did not venture into Springfield to church. But, on Sunday, March 26, 1676 sixteen men on horseback intended to take their families, escorted by Captain Nixon, to church for the baptism of Jabez. It was a fateful decision, as recorded in the History of Hadley:

On Sunday, the 26th of March, some of the people of Longmeadow, men and women, with children, ventured to ride to Springfield to attend public worship, in company with several Colony troopers. There were 16 or 18 men in all, but some had women behind them, and some had children in their arms, and when they were near Pecowsic Brooks 7 or 8 Indians in the bushes fired upon the hindmost and killed a man and a maid, wounded others, and took two women with their babes, and retired into a swamp. Six are said to have been slain or mortally wounded. John Keep, his wife Sarah, and his infant son Jabez are three of them. (The names of the others are not in the Spring Field records.) Those forward rode some distance towards Springfield, set down the women and maids, and then returned, but could not find the two women and children.” A letter from Major Savage [to the Governor’s Council] dated at Hadley, 28 Mar 1676, states “On the 26th inst. we had advice from Springfield that 8 Indians assaulted 16 to 18 men besides women and children as they were going to meeting from a public place they call Longmeadow, and killed a man and a maid, wounded 2 men and carried away captive 2 women and 2 children. In the night I sent 16 horse in pursuit of them, who met with some that were sent from Springfield, and overtook the Indians with the captives, who as soon as they saw the English, killed the 2 children and sorely wounded the women in the heads with their hatchets and so ran away into the swamp where they could not follow them. The scouts brought back both the women and the children. One of the women remained still senseless by reason of her wounds and the other is very sensible and rational.

John, Sarah and Jabez were all killed and buried in Springfield. Their only remaining son, Samuel, would carry on the Keep family name. The Nutting family of Groton suffered a similar fate at the hands of Indians in 1676 as well (see this Surname Saturday article). The Nutting and Keep families would intermarry later.

Dr. Nathan Cooley Keep

This descendant of John Keep was born in Longmeadow on December 23, 1800. At the age of fifteen Nathan went to Newark, New Jersey to apprentice as a jeweler. He returned to Longmeadow and after becoming interested in dentistry, moved to Boston to attend Harvard Medical School, graduating in 1827.

During his forty-year dentistry practice, Nathan invented several dental tools and is credited with the development of porcelain teeth. He was also a practicing physician and in 1847 was the first doctor to use anesthesia during childbirth, administering it to Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s wife Fanny.

In 1850 he participated in the Parkman murder trial in Boston. In November of 1849 Dr. George Parkman, he of one of the most prominent Boston families, vanished. A week after his disappearance a janitor found body parts hidden in the laboratory of chemistry professor John Webster.

Nathan was Parkman’s dentist and was able to identify the “mineral teeth” found to be those of his patient. His emotional testimony was recorded by the New York Globe:

Nathan was Parkman’s dentist and was able to identify the “mineral teeth” found to be those of his patient. His emotional testimony was recorded by the New York Globe:

I was in New York at the time of Dr. Parkman’s disappearance, and received a letter stating that his artificial teeth had been found in the furnace of Prof. Webster’s laboratory. I soon afterward returned to Boston, and the teeth were brought to me, and I at once recognized them as the teeth which I had made for Dr. Parkman…. [Here the voice of Dr. Keep was frequently interrupted by sobs, and he was finally obliged to wait for some time, until his emotions would allow him to proceed.]… I was satisfied that the right upper teeth which were put into my hands by Dr. Lewis, were Dr. P’s. There could be no mistake about them.

With those words, the fate of mild-mannered professor John Webster was sealed. Webster was convicted and publicly hanged in Boston’s Leverett Square on August 30, 1850. With Nathan Keep’s testimony, the field of forensic dentistry had been introduced.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Ghost Towns of the Mother Road: Valentine, Arizona

The area around what became known as Valentine, Arizona was established in 1898 when President William McKinley set aside land for an Indian School. By the way, if you missed Monday’s article about “Henry P. Ewing, The Blind Miner,” check it out here. Henry was the first superintendent of the Indian School.

The area around what became known as Valentine, Arizona was established in 1898 when President William McKinley set aside land for an Indian School. By the way, if you missed Monday’s article about “Henry P. Ewing, The Blind Miner,” check it out here. Henry was the first superintendent of the Indian School.

The location was first named Truxton for some landmarks (named after a local family), but in 1910 the town name was officially changed to Valentine in honor of Robert G. Valentine, Commissioner of Indian Affairs. After the Indian School was built, a separate school for Anglo children was built, referred to as “The Red Schoolhouse.”

This article has been updated and published in the June 2018 issue of Digging History Magazine. Other articles in this issue include: “On a Whim and a Bet: America’s First Coast-to-Coast Road Trip”, “Victorian Pastimes: Girdling the Globe”, “Victorian Fashion: Bicycles, Bloomers and Suffrage”, and more. Preview the issue here or purchase here.

This article has been updated and published in the June 2018 issue of Digging History Magazine. Other articles in this issue include: “On a Whim and a Bet: America’s First Coast-to-Coast Road Trip”, “Victorian Pastimes: Girdling the Globe”, “Victorian Fashion: Bicycles, Bloomers and Suffrage”, and more. Preview the issue here or purchase here.

I invite you to check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Henry P. Ewing, The Blind Miner

While researching possible topics for today’s article, I was thinking perhaps mining history and then ran across a link to a story about a blind miner in Mohave County, Arizona. Hmm … that sounds interesting, so I researched a bit further. Just the story about Henry Ewing as a blind miner is fascinating enough, but I thought there must be more to his story, and indeed there is. But, first the story of Henry P. Ewing, the blind miner.

While researching possible topics for today’s article, I was thinking perhaps mining history and then ran across a link to a story about a blind miner in Mohave County, Arizona. Hmm … that sounds interesting, so I researched a bit further. Just the story about Henry Ewing as a blind miner is fascinating enough, but I thought there must be more to his story, and indeed there is. But, first the story of Henry P. Ewing, the blind miner.

The astonishing tale of a blind miner in Mohave County began to show up in the local newspaper in 1906 after Henry had a few mishaps. In his book Arizona, Prehistoric, Aboriginal, Pioneer, Modern: The Nation’s Youngest Commonwealth Within a Land of Ancient Culture, Volume 2, James McClintock had a short paragraph about Henry:

A Blind Miner and His Work

Mohave County has given the world many instances of rare courage in its pioneer days, but nothing finer than the tale how a blind miner, Henry Ewing, unaided sunk a shaft on his Nixie mine, near Vivian, not far from the present camp of Oatman. It was in 1904, after Ewing, a gentleman of culture, had lost his eyesight. Despite the warning of friends, he

This article is no longer available for free at this site. It was re-written and enhanced (5-page article), complete with footnotes and sources and has been published in the June 2018 issue of Digging History Magazine. Should you prefer to purchase the article only, contact me for more information.

This article is no longer available for free at this site. It was re-written and enhanced (5-page article), complete with footnotes and sources and has been published in the June 2018 issue of Digging History Magazine. Should you prefer to purchase the article only, contact me for more information.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? That’s easy if you have a minute or two. Here are the options (choose one):

- Scroll up to the upper right-hand corner of this page, provide your email to subscribe to the blog and a free issue will soon be on its way to your inbox.

- A free article index of issues is available in the magazine store, providing a brief synopsis of every article published in 2018. Note: You will have to create an account to obtain the free index (don’t worry — it’s easy!).

- Contact me directly and request either a free issue and/or the free article index. Happy to provide!

Thanks for stopping by!