Tombstone Tuesday: Baron DeKalb Stansell

Baron DeKalb Stansell was born in Decatur, DeKalb County, Georgia on November 25, 1833 to parents David and Priscilla (Chastain) Stansell. DeKalb County was established in 1822 from parts of Henry, Gwinett and Fayette counties and named after Baron Johann de Kalb, a French military officer and Revolutionary War hero.

Baron DeKalb Stansell was born in Decatur, DeKalb County, Georgia on November 25, 1833 to parents David and Priscilla (Chastain) Stansell. DeKalb County was established in 1822 from parts of Henry, Gwinett and Fayette counties and named after Baron Johann de Kalb, a French military officer and Revolutionary War hero.

Baron de Kalb made his first visit to America in 1768 at the request of France’s foreign minister de Choiseul, a covert mission to find out what was really happening at that volatile time before the Revolutionary War. He returned in 1777 with Marquis de Lafayette and joined the Continental Army with the rank of Major General.

His dedication to the patriot cause was evident as he spent the winter that year at Valley Forge with Washington and Lafayette. De Kalb was later sent south to the Carolinas, although during the patriot defeat at the Battle of Camden was not in command. During that battle, De Kalb’s horse was shot from under him, causing him to fall to the ground. British soldiers shot him three times and stabbed him with a bayonet.

De Kalb and his aide Lieutenant Colonel Du Buysson were taken prisoners, yet the British officer tended to De Kalb’s wounds. Just before he died, de Kalb extended his hand in gratitude and said to the officer, “I thank you for your generous sympathy, but I died the death I always prayed for: the death of a soldier fighting for the rights of man.” Years later George Washington visited Camden and asked to see de Kalb’s grave. After viewing the grave for some time, Washington exclaimed, “So, there lies the brave De Kalb; the generous stranger who came from a distant land to fight our battles, and to water with his blood the tree of our liberty. Would to God he had lived to share its fruits!”1

De Kalb and his aide Lieutenant Colonel Du Buysson were taken prisoners, yet the British officer tended to De Kalb’s wounds. Just before he died, de Kalb extended his hand in gratitude and said to the officer, “I thank you for your generous sympathy, but I died the death I always prayed for: the death of a soldier fighting for the rights of man.” Years later George Washington visited Camden and asked to see de Kalb’s grave. After viewing the grave for some time, Washington exclaimed, “So, there lies the brave De Kalb; the generous stranger who came from a distant land to fight our battles, and to water with his blood the tree of our liberty. Would to God he had lived to share its fruits!”1

It seems likely that the son of David and Priscilla Stansell was named for this brave Frenchman and Revolutionary War hero. Baron remained in his father’s household until he married Caroline Jane “Carrie” Pritchard on May 9, 1861. The Civil War had just begun and the 1st Georgia Infantry Regiment had been formed in April in Macon. It’s unclear as to when Baron enlisted but his first child, Joshua Calvin, was born in 1862.

It appears that Private Baron Stansell was engaged in the Battle of Atlanta while serving in Company K of the 1st Georgia Infantry, since records indicate he was captured near there on August 7, 1864. He was first housed in a Union prison camp in Louisville, Kentucky then transferred to Camp Chase in Ohio. On March 18, 1865 he was transferred to Point Lookout, Maryland. When the war ended a few weeks later, he was released with other prisoners of war who eventually found their way home.

Baron and Carrie resided in Cobb County following the war where he farmed. Their family continued to grow: Sarah Ann Priscilla (1866); Margaret Elizabeth (1867); Mary Lomonia (1872); Hattie Delonia (1874); Colquitt (1876-died in infancy); Ida Corrine; Lillian Melessia (1880); James Elkin (1882) and William Arthur (1884).

In 1885 the Stansells left Cobb County and made their way to Cisco, Eastland County, Texas where they remained the rest of their lives. It appears that Carrie’s family (Pritchard) either came with them or were already in Texas because Baron was involved somehow (referred to as “B.D. Stansell”) in a case before the Texas State Supreme Court in October of 1886.

By 1900 their two youngest daughters and two youngest sons remained in their household. Carrie passed away on February 25, 1907 and three years later Ida, James and William were still residing with Baron, who still farmed at the age of seventy-six. The following year on June 10, 1911, Baron DeKalb Stansell passed away and was buried alongside Carrie in Cisco’s Oakwood Cemetery.

Most of their children remained in Cisco, but three married and moved elsewhere. Of interest to me were daughters Sarah (“Sallie”) and Lillian who migrated to West Texas and eastern New Mexico. Sarah married Richard Thomas Shields and was living near Petersburg, Texas when she died in 1925.2 Lillian married Luther Carmichael and they moved to Roosevelt County, New Mexico. After her children began attending Texas Technological College, Lillian maintained a second home in Lubbock to be near them. Following her husband’s death in 1930 she continued to manage their ranch in New Mexico, but retired in Lubbock where she died in 1962.3

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Feisty Females: Theodate Pope

Today’s feisty female, Theodate Pope Riddle, dared to be different. She was born at the stroke of midnight on February 2 (or 3), 1867 in Salem, Ohio to well-to-do parents Alfred Atmore and Ada Lunette (Brooks) Pope. Her birth name was Effie Brooks, but despising it so much and refusing to answer to it, at the age of nineteen she changed it to her grandmother’s first name (Theodate Stackpole). In part, she chose the name to honor her grandmother’s strong “belief in the Quaker principle of emphasizing the spiritual over the material.”3

Today’s feisty female, Theodate Pope Riddle, dared to be different. She was born at the stroke of midnight on February 2 (or 3), 1867 in Salem, Ohio to well-to-do parents Alfred Atmore and Ada Lunette (Brooks) Pope. Her birth name was Effie Brooks, but despising it so much and refusing to answer to it, at the age of nineteen she changed it to her grandmother’s first name (Theodate Stackpole). In part, she chose the name to honor her grandmother’s strong “belief in the Quaker principle of emphasizing the spiritual over the material.”3

Her family lived on Euclid Avenue in Cleveland, also known as “Millionaires’ Row”, but she wanted nothing to do with the path young women born to wealth were expected to travel from debutante to society matron. Alfred and Ada were so busy with their lives – he as an iron tycoon and she as a societal matron – that there was scarcely any family time together. Theodate once wrote that she had no memory of ever sitting on her mother’s lap.

Perhaps it was her education at Miss Porter’s School in Farmington, Connecticut that sparked a desire to step away from the societal norms of the day. Her parents sent her there, no doubt expecting her to return to Cleveland and take her proper place in society. Sarah Porter founded her school in 1843 with only eighteen students, growing to prominence as more parents sent their daughters to receive a progressive education. Of course, young women were still expected to someday take their proper place in society and wives and mothers – that was tradition.

Perhaps it was her education at Miss Porter’s School in Farmington, Connecticut that sparked a desire to step away from the societal norms of the day. Her parents sent her there, no doubt expecting her to return to Cleveland and take her proper place in society. Sarah Porter founded her school in 1843 with only eighteen students, growing to prominence as more parents sent their daughters to receive a progressive education. Of course, young women were still expected to someday take their proper place in society and wives and mothers – that was tradition.

The school’s curriculum went beyond the traditional, however, and offered such courses as Latin, French, German, trigonometry, astronomy, geology, chemistry and more. Each student was allowed to select the courses that best met her needs and talents. Participation in the arts and physical exercise were also emphasized.

After graduating from Miss Porter’s School, Theodate traveled abroad through Europe in 1888 and actually began to have a closer relationship with her father. Her father, an art collector, took her to galleries, searching for paintings to add to his collection. Theodate was not impressed with Paris, however, but loved the English countryside and the country homes. From the age of ten she had sketched plans for homes and dreamed of one day designing and building her own farmhouse.

The tour of Europe brought father and daughter closer together and Alfred was the one who suggested she consider a career in architecture. However, at the time architecture wasn’t a field open to women. Never mind that – Theodate returned home and created her own architectural education by hiring private tutors from Princeton’s art department.

With her father’s blessing, she purchased a house on forty-two acres in Farmington. She restored the house, an eighteenth century cottage, and named it “The O’Rourkery”. Alfred planned to retire in Farmington and wanted a house built where he could display his art collection, an impressive one that included works by Monet, Whistler and Degas. Her father suggested she design the house under the supervision of an architectural firm.

Theodate, being the strong-willed young woman she was, acquiesced to her father’s suggestion – with a twist. Her father suggested a firm and she wrote to the founding partner of McKim, Mead & White, William Rutherford Mead. In no uncertain terms she declared her intention to use her own plans and make her own decisions – the house would be a “Pope house” rather than a McKim, Mead & White-designed house.

It was an exhausting project for an apprentice but paved the way for a successful career path as a practicing architect. By 1910 she was fully accredited – the first female architect licensed in Connecticut. Three years later Alfred died and Theodate determined someday to build a boys preparatory school in his honor.

The campus would look like a quaint New England town with shops, town hall, post office and a working farm. The curriculum would emphasize character-building and students required to perform community service. Her most ambitious project had been completed earlier when the Westover School for Girls was established in Middlebury, Connecticut in 1909. The school’s architecture is still highly regarded, even today.

Even though she had become a seasoned and successful professional there were still those who refused to accept her as a female architect. In 1914 she was to be featured in a book honoring prominent New York architects. The publisher, however, upon learning that Theodate was a woman’s name, refused to include her photograph. In addition, her work had left her physically and emotionally depleted, slipping into one of her periodic bouts with depression.

A trip abroad was in order and on May 1, 1915, Theodate boarded a ship in New York with her companion and friend, Edwin Friend, and her maid Emily Robinson. It turned out to be a fateful journey for many, however, as the RMS Lusitania was torpedoed and sunk by a German U-20 submarine off the coast of Ireland on May 7. Almost twelve hundred people lost their lives, most dying by drowning or hypothermia – Theodate, however, was one of the survivors.

Passengers had been awakened at 5:30 a.m. on the 6th to see crew members running emergency drills. Although the voyage had been largely uneventful to that point, there was an uneasiness which hung over it all. On the morning of the scheduled departure an ominous notice had appeared on the shipping pages of various New York City newspapers. The German Embassy reminded readers about the war zone (World War I was in full swing in Europe by this time, although the United States had not yet joined their allies), cautioning that “vessels flying the flag of Great Britain, or of any of her allies, are liable to destruction.” Traveling on one of these ships was to be undertaken at one’s own risk.

No specific ship was named but the notice was positioned next to an advertisement for one of Cunard’s most luxurious liners at the time, the Lusitania. Several passengers no doubt had read the morning newspaper, and the veiled threat became a popular topic of conversation once the ship sailed. Theodate was convinced the Germans intended to target the Lusitania, but also believed that, like many ocean liners during that volatile time, would be convoyed to safety by the British navy.

Theodate and Edwin were lunching on the 7th with another party and one guest at the table jokingly remarked after ice cream was served that “he would hate to have a torpedo get him before he ate it.”4 Theodate and Edwin exited the dining room to the tune of The Blue Danube and began a stroll together on the B Deck promenade. Turning a corner, they heard a “dull explosion”, water and timbers flew past and Edwin struck his fist with his other hand and exclaimed, “By Jove, they’ve got us!”

They immediately ran inside but were thrown against a wall as the ship began listing starboard. Having previously agreed to meet friends on the Boat Deck portside in case of an emergency, Theodate and Edwin headed that way. The deck was crowded, time was running out and finding a good place to jump from was difficult. They saw a lifeboat which was rapidly filling, and although Edwin urged his friend to get in without him, she refused because there were other women still in need of rescue.

LusitaniaThey came upon Emily the maid and decided instead to locate life jackets. They found three and quickly tied them on, but the ship was going down so quickly it was time to jump. Theodate urged Edwin to jump first; she and Emily waited until he resurfaced before making their own. Immediately upon reaching the water, Theodate found herself sinking between the two decks and wondering if in her life she had “made good.”

Opening her eyes, she saw the lifeboat’s keel just above her, but hit her head which temporarily affected her vision. She surfaced and saw a “hundred of frantic, screaming, shouting humans in this grey and watery inferno.” A man without a life jacket panicked and jumped on her shoulders for flotation and she pleaded with him to stop. He let go and then Theodate lost consciousness and went back under.

After re-surfacing and regaining consciousness she saw people at a distance from her and looked around for Edwin – he was nowhere in sight. Theodate headed toward a stray oar, thinking the scene “too horrible to be true” and lost consciousness again. That evening she was found by a trawler and fished out with boat hooks, laid on the deck, presumed dead. A fellow passenger, Belle Naish, spotted her and couldn’t believe her friend was dead. Belle asked the crew to provide resuscitation and after two hours her breathing returned to normal. It wasn’t until about 10:30 p.m. that Theodate realized what had happened and she was safe. At this point, however, she had no recollection of the day’s events.

She was taken to a “third-rate” hotel, as she recollected it later, to receive care. Theodate, still worried over Edwin’s fate, could not sleep. Another passenger later searched for him but to no avail. As a result of the shock of Edwin’s apparent death, her hair began to fall out. Theodate recovered and rewarded Belle with a pension life in gratitude for saving her life.

All her life Theodate considered herself a fiercely independent woman, a suffragist, and not particularly enamored with the idea of marriage. However, on May 6, 1916 she married a former Russian ambassador, John Wallace Riddle. She resumed her architectural career, and in 1920 purchased land to build the boys school which would honor her father, naming it Avon Old Farms. That project, with its unusual building design and progressive curriculum, would occupy her time for years to come.

The school closed during World War II and converted to Old Farms Convalescent Hospital for blinded Army veterans. In 1947 the school reopened, and today, as is the case with the Westover School, still a highly regarded architectural work. She and her husband traveled extensively and moved to Argentina for a time while he served as an ambassador.

The home she had designed and built for her parents became the Hill-Stead Museum, a public facility housing an exquisite art collection, as stipulated in her will. Theodate Pope Riddle died on August 30, 1946 at her home in Farmington. Although she had no children of her own, she left behind a legacy of education, as well as art and stunning architecture, to future generations.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Tombstone Tuesday: Aunt Lizzie Devers (Too Tough to Die)

I could just as well tell her story under the “Feisty Female” category of this blog, but I’m choosing to write about the woman known to the country throughout the 1930’s until her death in 1946 as “Aunt Lizzie Devers”. To research her entire life, however, would be a monumental challenge for even the most experienced and well-seasoned genealogist. In fact, there is only one person on Ancestry.com who has attempted and I’m not sure whether it’s correct or not.

I could just as well tell her story under the “Feisty Female” category of this blog, but I’m choosing to write about the woman known to the country throughout the 1930’s until her death in 1946 as “Aunt Lizzie Devers”. To research her entire life, however, would be a monumental challenge for even the most experienced and well-seasoned genealogist. In fact, there is only one person on Ancestry.com who has attempted and I’m not sure whether it’s correct or not.

If the hundreds of newspaper articles written about her are to be believed, however, Aunt Lizzie Devers had quite an interesting history. The following is compiled from those 1930’s and 1940’s newspaper articles.

If the hundreds of newspaper articles written about her are to be believed, however, Aunt Lizzie Devers had quite an interesting history. The following is compiled from those 1930’s and 1940’s newspaper articles.

I can’t say what her full birth name was, except her first name was probably Elizabeth since she went by Lizzie. Her father was said to have been full-blood Cherokee and her mother Dutch-Irish. The only definitive census records which indicate her Native American ancestry are for the years 1930 and 1940 where she is clearly enumerated as “Indian”.

This extensive article is no longer available on this site. However, it was enhanced and published in the September 2018 issue of Digging History Magazine. Aunt Lizzie was quite a colorful character — her story is not to be missed. Should you prefer to purchase the article only, contact me for more information.

This extensive article is no longer available on this site. However, it was enhanced and published in the September 2018 issue of Digging History Magazine. Aunt Lizzie was quite a colorful character — her story is not to be missed. Should you prefer to purchase the article only, contact me for more information.

I invite you to check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Ghost Town Wednesday: Tee Pee City, Texas

This ghost town in Motley County, Texas was once a Comanche village near where Tee Pee Creek merges with the middle fork of the Pease River. In 1875 it was established as one of the first Texas Panhandle settlements as a buffalo hunting and surveyor camp by Charles Rath and Lee Reynolds.

This ghost town in Motley County, Texas was once a Comanche village near where Tee Pee Creek merges with the middle fork of the Pease River. In 1875 it was established as one of the first Texas Panhandle settlements as a buffalo hunting and surveyor camp by Charles Rath and Lee Reynolds.

Rath and Reynolds brought the town with them when they arrived from Dodge City, Kansas, hauling in wagons, cattle, mules and dance hall equipment. Of the one hundred-wagon train of settlers who had departed Kansas with them, about a dozen families remained to become the first settlers of Motley County. Rath and Reynolds later moved on to the Double Mountain Fork of the Brazos and left others to run the camp.

Rath and Reynolds brought the town with them when they arrived from Dodge City, Kansas, hauling in wagons, cattle, mules and dance hall equipment. Of the one hundred-wagon train of settlers who had departed Kansas with them, about a dozen families remained to become the first settlers of Motley County. Rath and Reynolds later moved on to the Double Mountain Fork of the Brazos and left others to run the camp.

Some of the first homes were crude dugouts built into the creek bank and covered with brush and grass, temporary housing while waiting until more appropriate building materials could be purchased. Picket houses were built with Chinaberry poles left behind by the Comanches and plastered with mud. According to the Famous Trees of Texas web site, the town was logically named Tee Pee City.

Isaac O. Armstrong and his partner were left to oversee operations in the camp after Rath and Reynolds moved on. Armstrong was the proprietor of a two-room picket building – one room a hotel and one a saloon complete with dance hall girls. He was also the owner of a general store which sold supplies to buffalo hunters in the area.

The buffalo herds were plentiful and the hides traded in Tee Pee City were the greatest source of income for the camp as hunters exchanged them for ammunition and food. A post office was established in 1879 with A.B. Cooper serving as the first postmaster, and in 1880 there were twelve individuals enumerated in the camp for the census. By the beginning of the 1880’s, however, the buffalo herds had been depleted.

A school was later established and used from 1895 until 1902, but after the herds were diminished the camp was more famously known for its dance and gambling halls, street brawls and shootings. Texas Ranger George W. Arrington and his men were often called from their camp in Blanco Canyon to restore order.

The railroad bypassed the area, but ultimately the camp’s lawlessness and rowdiness was its downfall. The owners of the nearby Matador Ranch ordered their cowboys to avoid Tee Pee City and its corrupting influences. The owners bided their time and in 1904 purchased the land and shut the camp down permanently.

Today, a Texas State Historical Marker and a small cemetery, where Isaac Armstrong and two young children of A.B. Cooper and their aunt are buried, are all that remain at the site.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Tombstone Tuesday: What Really Happened to Sidney Pettit?

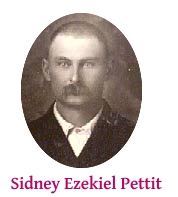

In case you missed last week’s Tombstone Tuesday article, you might want to read it first since I promised to clear up the mystery of what really happened to the son of Ezekiel and Ella Pettit. The story posted by a family friend at Find-A-Grave left me with more questions than answers, and this compelled me to do a little digging to discover what really happened to Sidney Ezekiel Pettit.

In case you missed last week’s Tombstone Tuesday article, you might want to read it first since I promised to clear up the mystery of what really happened to the son of Ezekiel and Ella Pettit. The story posted by a family friend at Find-A-Grave left me with more questions than answers, and this compelled me to do a little digging to discover what really happened to Sidney Ezekiel Pettit.

The following information for Sidney was posted at Find-A-Grave:

Birth: Sep. 2, 1886

Boulder

Boulder County

Colorado, USA

Death: Jan. 9, 1906

Carbondale

Garfield County

Colorado, USA

Sidney E. Pettit was the youngest son of Ezekiel & Ella Pettit. Born Sept. 2nd 1886, he was killed on Jan. 9th 1906 near Carbunkle Colorado. His body was never recovered and lies today in that now abandoned silver mine. Since he had no grave his name was added to his mother’s grave stone upon her death in Nov. 1915.

Sidney E. Pettit was the youngest son of Ezekiel & Ella Pettit. Born Sept. 2nd 1886, he was killed on Jan. 9th 1906 near Carbunkle Colorado. His body was never recovered and lies today in that now abandoned silver mine. Since he had no grave his name was added to his mother’s grave stone upon her death in Nov. 1915.

This is just a snippet as this article was enhanced with new research and featured in the September-October 2019 issue of Digging History Magazine. If interested in purchasing a subscription to the magazine, you can receive this issue for free upon request (see subscription details below).

Did you enjoy this article snippet? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article snippet? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Yankee Doodle “Dandies”: Silk Stocking Regiments

The Upper East Side is one of the most affluent neighborhoods in New York City and once referred to as the “Silk Stocking District”. Within its boundaries lies some of the most expensive real estate in the country, home to some of the wealthiest people in the world. Through the years the area has been home to Rockefellers, Roosevelts, Kennedys and Astors, just to name a few prominent families.

The Upper East Side is one of the most affluent neighborhoods in New York City and once referred to as the “Silk Stocking District”. Within its boundaries lies some of the most expensive real estate in the country, home to some of the wealthiest people in the world. Through the years the area has been home to Rockefellers, Roosevelts, Kennedys and Astors, just to name a few prominent families.

During the Civil War, the Confederate cause was often referred to as a “rich man’s war, poor man’s fight” since certain men of wealth and stature could pay someone to fight in their stead. After the Enrollment Act was passed in Congress in 1863, that term applied throughout the North as well since the new law provided two ways to avoid the draft: substitution or commutation.

During the Civil War, the Confederate cause was often referred to as a “rich man’s war, poor man’s fight” since certain men of wealth and stature could pay someone to fight in their stead. After the Enrollment Act was passed in Congress in 1863, that term applied throughout the North as well since the new law provided two ways to avoid the draft: substitution or commutation.

This article is no longer available for free at this site. It was re-written and enhanced, complete with footnotes and sources and has been published in the April 2018 issue of Digging History Magazine. Should you prefer to purchase the article only, contact me for more information.

This article is no longer available for free at this site. It was re-written and enhanced, complete with footnotes and sources and has been published in the April 2018 issue of Digging History Magazine. Should you prefer to purchase the article only, contact me for more information.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Feisty Females: Neta Snook

When Amelia Earhart wanted to learn how to fly an airplane, the deal she struck with her parents required she be taught by a woman pilot. That pilot, Neta Snook, was a woman of many “firsts” – one of the first female aviators, she was the first woman accepted into a flying school, the first to run a commercial airfield and the first woman to run her own aviation business.

When Amelia Earhart wanted to learn how to fly an airplane, the deal she struck with her parents required she be taught by a woman pilot. That pilot, Neta Snook, was a woman of many “firsts” – one of the first female aviators, she was the first woman accepted into a flying school, the first to run a commercial airfield and the first woman to run her own aviation business.

Mary Anita “Neta” Snook was born in Mount Carroll, Illinois on February 14, 1896 to parents Floyd and Adella Snook. At an early age Neta was fascinated with machinery and shared her father’s love of automobiles. Her father allowed her to sit on his lap at the age of four and steer his Stanley Steamer and taught her the inner workings of the car as well.

Mary Anita “Neta” Snook was born in Mount Carroll, Illinois on February 14, 1896 to parents Floyd and Adella Snook. At an early age Neta was fascinated with machinery and shared her father’s love of automobiles. Her father allowed her to sit on his lap at the age of four and steer his Stanley Steamer and taught her the inner workings of the car as well.

This article is no longer available for free at this site. It was re-written and enhanced (11-page article), complete with footnotes and sources and has been published in the November 2018 issue of Digging History Magazine. Should you prefer to purchase the article only, contact me for more information. This issue featured several articles on World War I, the Great War, including: “Mining Genealogical Gold: Finding Records of the Great War (and the stories behind them)”, “Rolling Up Their Sleeves: World War I and the Road to Suffrage”, “Pandemic! On the Home Front: Blue as Huckleberries and Spitting Blood” and more).

I invite you to check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

I invite you to check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

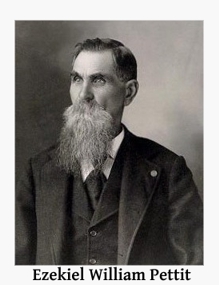

Tombstone Tuesday: Ezekiel William Pettit

Ezekiel William Pettit was born in 1837 to parents Samuel and Polly Pettit in the province of Ontario, Canada, not far from the United States border in the township of Townsend. One source indicates that his parents were actually United States citizens, but there are some conflicting records that seem to indicate otherwise. Through the years, some census records indicated that Ezekiel’s parents were both born in Canada and some indicate they were born in New York.

Ezekiel William Pettit was born in 1837 to parents Samuel and Polly Pettit in the province of Ontario, Canada, not far from the United States border in the township of Townsend. One source indicates that his parents were actually United States citizens, but there are some conflicting records that seem to indicate otherwise. Through the years, some census records indicated that Ezekiel’s parents were both born in Canada and some indicate they were born in New York.

In 1851 the Pettit family was enumerated in Norfolk County, Ontario and both parents were listed as being born in “Upper Canada” (there was a “ditto” notation for an entry above theirs). The family moved to Rockford, Illinois sometime after that census, perhaps 1852 according to one source, although a later record (the 1900 census) indicated that Ezekiel had immigrated in 1847 (probably a miscalculation since the family was clearly living in Canada for the 1851 census).

In 1851 the Pettit family was enumerated in Norfolk County, Ontario and both parents were listed as being born in “Upper Canada” (there was a “ditto” notation for an entry above theirs). The family moved to Rockford, Illinois sometime after that census, perhaps 1852 according to one source, although a later record (the 1900 census) indicated that Ezekiel had immigrated in 1847 (probably a miscalculation since the family was clearly living in Canada for the 1851 census).

This is just a snippet as this article was enhanced with new research and featured in the September-October 2019 issue of Digging History Magazine. If interested in purchasing a subscription to the magazine, you can receive this issue for free upon request (see subscription details below).

Did you enjoy this article snippet? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article snippet? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Far-Out Friday: This Might Have Been a Victorian Thing (Get Me Out of Here, I’m Not Dead!)

A friend forwarded a story to me recently from Retro Indy (Indianapolis) about a device invented in the late eighteenth century, which led me to explore a bizarre series of patents granted from the 1840’s through the early twentieth century. The September 20, 1963 issue of Life magazine suggested that one peculiarity of the nineteenth century, the fear of being buried alive, may have been inspired by Edgar Allan Poe’s creepy stories. Victorians had a “thing” about death.

A friend forwarded a story to me recently from Retro Indy (Indianapolis) about a device invented in the late eighteenth century, which led me to explore a bizarre series of patents granted from the 1840’s through the early twentieth century. The September 20, 1963 issue of Life magazine suggested that one peculiarity of the nineteenth century, the fear of being buried alive, may have been inspired by Edgar Allan Poe’s creepy stories. Victorians had a “thing” about death.

This article has been removed from the web site, but will be featured in the September-October 2019 issue of Digging History Magazine. It will be updated, complete with footnotes and sources. Trust me — you don’t want to miss it! Other articles scheduled for that issue include “Ways to Go in Days of Old” and “O, Victoria, You’ve Been Duped!”.

This article has been removed from the web site, but will be featured in the September-October 2019 issue of Digging History Magazine. It will be updated, complete with footnotes and sources. Trust me — you don’t want to miss it! Other articles scheduled for that issue include “Ways to Go in Days of Old” and “O, Victoria, You’ve Been Duped!”.

I invite you to check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads, just carefully-researched stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? That’s easy if you have a minute or two. Here are the options (choose one):

- Scroll up to the upper right-hand corner of this page, provide your email to subscribe to the blog and a free issue will soon be on its way to your inbox.

- A free article index of issues is available in the magazine store, providing a brief synopsis of every article published in 2018. Note: You will have to create an account to obtain the free index (don’t worry — it’s easy!).

- Contact me directly and request either a free issue and/or the free article index. Happy to provide!

Thanks for stopping by!

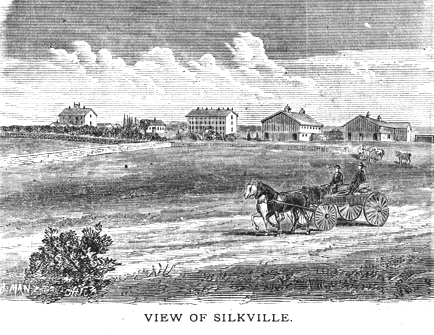

Ghost Town Wednesday: Silkville, Kansas (Socialism Doesn’t Work)

It would be more appropriate to call today’s ghost town a “ghost commune”, established by Ernest Valeton de Boissère in 1869. He was a wealthy Frenchman, born into a Bordeaux aristocratic family in 1810. When Napoleon III came into power after the Third French Revolution, de Boissère departed France in 1852 for political reasons and immigrated to America.

It would be more appropriate to call today’s ghost town a “ghost commune”, established by Ernest Valeton de Boissère in 1869. He was a wealthy Frenchman, born into a Bordeaux aristocratic family in 1810. When Napoleon III came into power after the Third French Revolution, de Boissère departed France in 1852 for political reasons and immigrated to America.

Did you enjoy this article snippet? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. This article has been updated significantly with new research and published in the July-August 2019 issue of the magazine. The magazine is on sale in the Digging History Magazine store and features these stories (100+ pages of stories, no ads):

Did you enjoy this article snippet? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. This article has been updated significantly with new research and published in the July-August 2019 issue of the magazine. The magazine is on sale in the Digging History Magazine store and features these stories (100+ pages of stories, no ads):

- “Drought-Locusts-Earthquakes-B-Blizzards (Oh My!)” – Perhaps no state is possessive of a more appropriate motto than Kansas: Ad Astra per Aspera (“To the stars through difficulties”, or more loosely translated “a rough road leads to the stars”1). By the time the state adopted its motto in 1876, fifteen years post-statehood, it had experienced not only a brutal, bloody beginning (“Bloody Kansas”) but had endured (and continued to struggle with) extreme pestilence, preceded by severe drought and even an earthquake in April 1867. In the early days being Kansan was not for the faint of heart.

- “Home Sweet Soddie” – For years The Great Plains had been a vast expanse to be endured on the way to California and Oregon. Now the United States government was making 270 million acres available for settlement – practically free if, after five years, all criteria had been met. The criteria, referred to as “proving up” meant improvements must be made (and proof provided) by cultivating the land and building a home. For many their first home would be a dugout, a sod-covered hole in the ground.

- “Wholesale Murder at Newton” – It’s called “The Gunfight at Hyde Park” or the “Newton Massacre”. One newspaper headlined it as “Wholesale Murder at Newton”, another called it an “affray” and another a “riot”. Whatever, it was bloody, and one of the biggest gunfights in the history of the Wild West, more deadly than the legendary gunfight at the OK Corral.

- “Kansas Ghost Towns” – It might be more appropriate to call this Kansas ghost town, established by Ernest Valeton de Boissière in 1869, a “ghost commune” (Silkville). Nicodemus. There was something genuinely African in the very name. White folks would have called their place by one of the romantic names which stud the map of the United States, Smithville, Centreville, Jonesborough; but these colored people wanted something high-sounding and biblical, and so hit on Nicodemus.

- “The Land of Odds: Kwirky Kansas” – For some of us the mention of Kansas invokes memories of one of the classic films of our childhood, The Wizard of Oz. With a tongue-in-cheek reference this article highlights some of the state’s history and people in a series of vignettes – some serious, some not so serious (the real “oddballs”) in a light-hearted fashion. A rollicking fun article covering a range of Kansas “oddities” and “oddballs”, including one of the most dangerous quacks to have ever practiced medicine, Dr. John R. Brinkley.

- “Mining Kansas Genealogical Gold” – One of my favorite “adventures in research” is to discover obscure genealogical records or perhaps stumble across a set of records at Ancesty.com or Fold3 which turns out to be a gold mine of information. This article highlights some real gems available at Ancestry.

- “Chautauqua: The Poor Man’s Educational Opportunity” – During an era spanning the mid-1870s through the early twentieth century, Kansans, like many Americans across the country, anticipated the summer season known as Chautauqua, an event Theodore Roosevelt called “the most American thing in America”. By 1906 when Roosevelt made such an astute observation the movement had evolved into a non-sectarian gathering, where “all human faiths in God are respected. The brotherhood of man recreating and seeking the truth in the broad sunlight of love, social co-operation.”

- And more, including book reviews and tips for finding elusive genealogical records.

Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!