Far-Out Friday: “Passing Strange”

Clarence King, a Yale-educated geologist, surveyed the American West and served as the first director of the United States Geological Survey. His close friend Henry Adams said that he had “that combination of physical energy, social standing, mental scope and training, wit, geniality and science, that seemed superlatively American and irresistibly strong.”

Clarence King, a Yale-educated geologist, surveyed the American West and served as the first director of the United States Geological Survey. His close friend Henry Adams said that he had “that combination of physical energy, social standing, mental scope and training, wit, geniality and science, that seemed superlatively American and irresistibly strong.”

At the age of twenty-two Clarence served as a volunteer geologist in the 1864 Survey of California, crossing the country with a group of pioneers who departed from St. Joseph, Missouri. His skills as a geologist astounded his co-workers – he scaled mountains, named peaks and drew extremely accurate maps.

This article has been removed from the web site, but will be featured in the September-October 2019 issue of Digging History Magazine. It will be updated, complete with footnotes and sources. Trust me — you don’t want to miss it! Other articles scheduled for that issue include “Ways to Go in Days of Old” and “O, Victoria, You’ve Been Duped!”.

This article has been removed from the web site, but will be featured in the September-October 2019 issue of Digging History Magazine. It will be updated, complete with footnotes and sources. Trust me — you don’t want to miss it! Other articles scheduled for that issue include “Ways to Go in Days of Old” and “O, Victoria, You’ve Been Duped!”.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? That’s easy if you have a minute or two. Here are the options (choose one):

- Scroll up to the upper right-hand corner of this page, provide your email to subscribe to the blog and a free issue will soon be on its way to your inbox.

- A free article index of issues is available in the magazine store, providing a brief synopsis of every article published in 2018. Note: You will have to create an account to obtain the free index (don’t worry — it’s easy!).

- Contact me directly and request either a free issue and/or the free article index. Happy to provide!

Thanks for stopping by!

Off the Map: Ghost Towns of the Mother Road – Amboy, California

The Amboy, California area was settled in the late 1850’s but wasn’t established as a town until 1883 or 1884. The town was named Amboy as part of civil engineer Lewis Kingman’s plan to alphabetically name a series of railroad stations across the Mojave Desert for the Atlantic and Pacific Railroad. Following Amboy would be Bolo (renamed Bristol), Chambless, Danby, Essex, Fenner, Goffs and so on. Because these railroad stops were so vital it is said that the railroad was the organization responsible for naming more towns in California in those days.

The Amboy, California area was settled in the late 1850’s but wasn’t established as a town until 1883 or 1884. The town was named Amboy as part of civil engineer Lewis Kingman’s plan to alphabetically name a series of railroad stations across the Mojave Desert for the Atlantic and Pacific Railroad. Following Amboy would be Bolo (renamed Bristol), Chambless, Danby, Essex, Fenner, Goffs and so on. Because these railroad stops were so vital it is said that the railroad was the organization responsible for naming more towns in California in those days.

When gold was discovered nearby in the late 1890’s the town began to boom. In 1926 the National Trails Highway (became Route 66) opened and Amboy was a major stop along that road. Even through the Depression years, Amboy didn’t fade much – travelers still needed a place to get gas, eat or sleep.

In 1938 Roy and Velma Crowl bought a gas station and café in Amboy which eventually became the now famous Roy’s Café and Motel. Herman “Buster” Burris partnered with his father-in-law Roy to build up the town (and their business) by adding a motor court (motel) for weary travelers. According to a January 17, 2007 Los Angeles Times article:

Amboy was the domain of Buster Burris, a rough-hewn entrepreneur with flinty eyes, sun-toasted skin and strong opinions about rowdy bikers and men with long hair. Burris and his father-in-law opened Roy’s in the 1930s and for decades did brisk business selling tires, thick malts and overpriced gas. At times so many cars awaited service that one might have thought they were running a used car lot too.

So even through the World War II years, Amboy continued to thrive as a small town stop on Route 66 although there were less than 100 residents. With the 1972 construction of Interstate 40 and the by-pass of old Route 66, the town began to decline, although people still wanted to stop for the nostalgia – Roy’s Café was known to be an excellent dining stop. Again, from the 2007 Times article:

So even through the World War II years, Amboy continued to thrive as a small town stop on Route 66 although there were less than 100 residents. With the 1972 construction of Interstate 40 and the by-pass of old Route 66, the town began to decline, although people still wanted to stop for the nostalgia – Roy’s Café was known to be an excellent dining stop. Again, from the 2007 Times article:

Their place hummed 24/7 with broken-down cars — so many that customers often had a long wait. So Crowl and Burris opened a diner to feed them double cheeseburgers and homemade chili. The boom in tourism after World War II brought even more stranded motorists. So Crowl and Burris built the motel and in 1959 erected the Roy’s sign.

Burris sold the town in 2000 before he died at the age of 92 – the new owners, however, defaulted and the property reverted back to Buster’s second wife, Bessie. She sold it again in 2005 for $425,000 cash to the founder of the Juan Pollo restaurant chain, Albert Okura. Apparently his promise to rebuild Roy’s sealed the deal. Okura seems determined to restore the town although there wasn’t much structure-wise included in the purchase. According to the Times article, Burris is said to have bulldozed quite a bit of the town when I-40 wrecked his business.

One amusing story I found dated from the 1930’s when local high school students decided to stage a “geological prank” (one source said it was a deputy sheriff!). That stretch of highway was infamous for broken down cars and flat tires strewn about and with a recent newly laid railroad track there were also old timbers scattered about – an eyesore. The students began to gather the “junk” over a period of months and then headed to the nearby Amboy Crater, dumped the debris and set it afire. The local residents panicked thinking the “volcano” was about to erupt!

Amboy is also known for its Salt Ponds – this picture is stunning! Hopefully, Albert Okura will be able to fulfill his promise to restore Roy’s Café and the town of Amboy. Nostalgic places like Amboy, California deserve a chance to be remembered for what they once were – back in the good old days.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

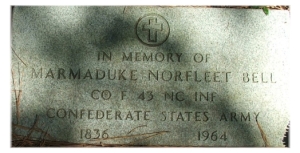

Tombstone Tuesday: Marmaduke Norfleet Bell

Marmaduke Norfleet Bell (III) was born in 1836 to parents Marmaduke Norfleet Bell, Jr. and Mary “Polly” Landing (or Landen) Bell. Marmaduke and Polly were married on February 23, 1826 and had seven children listed in the 1850 United States Census. That year, Marmaduke III was listed as being fifteen years old.

Marmaduke Norfleet Bell (III) was born in 1836 to parents Marmaduke Norfleet Bell, Jr. and Mary “Polly” Landing (or Landen) Bell. Marmaduke and Polly were married on February 23, 1826 and had seven children listed in the 1850 United States Census. That year, Marmaduke III was listed as being fifteen years old.

Marmaduke III paid a one thousand dollar bond to the State of North Carolina and obtained a license to marry (Margaret) Ann Walston on March 26, 1859 in Halifax County, North Carolina.

In 1860, Ann and Marmaduke’s first child Hassell was born. In June of 1861, daughter Virginia “Jennie” was born and on January 2, 1864 daughter Sarah was born. On February 4, 1862, Marmaduke enlisted in Company F of the North Carolina 43rd Infantry Regiment and was mustered in as a Private on April 2, 1862. On July 26, 1862, Marmaduke was promoted to Full Corporal.

The regiment had been organized at Camp Mangum in March of 1862, located about three miles west of Raleigh. The entire brigade was first dispatched to Wilmington and Fort Johnson on the Cape Fear River, remaining approximately one month and then advanced to Virginia. While occupying the road around Richmond the brigade came under fire from gunboats and Malvern Hill. Afterwards they were ordered to Drewry’s Bluff and became part of the forces led by Major General G.W. Smith, providing protection for Richmond in advance of General Lee’s troops which would advance to Maryland in September 1862.

The regiment had been organized at Camp Mangum in March of 1862, located about three miles west of Raleigh. The entire brigade was first dispatched to Wilmington and Fort Johnson on the Cape Fear River, remaining approximately one month and then advanced to Virginia. While occupying the road around Richmond the brigade came under fire from gunboats and Malvern Hill. Afterwards they were ordered to Drewry’s Bluff and became part of the forces led by Major General G.W. Smith, providing protection for Richmond in advance of General Lee’s troops which would advance to Maryland in September 1862.

After fortifying their quarters for winter the brigade was ordered to move to Goldsboro to reinforce other Confederates in advance of Union troops led by General Foster. The Union managed to burn a bridge which the Confederates quickly rebuilt. From early 1863 to late spring, the regiment experienced a few skirmishes, but nothing of much consequence. However, in June orders came through to begin to join General Lee at Brandy Station. The Union suffered heavy losses in that battle. Then it was on to Carlisle, Pennsylvania for that fateful battle at Gettysburg.

Youngest daughter, Sarah, was born on January 2, 1864, so apparently Marmaduke had secured at least a short leave sometime in 1863. On March 30, 1864, Marmaduke was promoted to Full Sergeant. By July the 43rd had advanced to Harper’s Ferry and by the 11th of July they were in sight of U.S. Capitol Dome in Washington, D.C. At this point, the 43rd had marched some five hundred miles and had participated in twelve battles or skirmishes which resulted in severe losses for the enemy.

The troops crossed the Blue Ridge at Snicker’s Gap on July 17 and that afternoon had driven the enemy into the river where several were killed or drowned. On the following day the Union returned and a major battle ensued. That day, July 18, Sergeant Marmaduke Norfleet Bell was mortally wounded. While there is a grave marker in North Carolina, it is doubtful that was his final resting place. I found no other family members in the cemetery where the marker is located.

I’m not sure if Marmaduke had ever met his daughter Sarah before heading into the heightened engagements of 1864. In 1870, twenty-six year old Margaret (Ann) was enumerated with the Watson family in Palmyra, Halifax, North Carolina. Her three children were ten (Hassell), nine (Jennie) and seven (Sarah). It doesn’t appear that Ann ever remarried after being widowed in 1864.

One other note about Marmaduke and his full name “Marmaduke Norfleet” – I suspect he is named after some ancestor. It appears that his great grandmother’s maiden name was Norfleet. There was a Marmaduke Norfleet, born in 1700 who sold land (swamp land, that is) to none other than George Washington in the 1760’s. Read about it here – it’s pretty interesting.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Honoring the Fallen: Ladies Hollywood Memorial Association

The Ladies Hollywood Memorial Association was founded at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church on May 3, 1866 and chartered on January 19, 1891. The group’s primary duties were to care for and honor the graves of the Confederate soldiers buried in Richmond’s Hollywood Cemetery, and they were one of many such associations organized by the women of the South. Indeed, immediately after the fall of the Confederacy these women sprang into action.

The Association’s primary objective was to care for and prevent the neglect of the graves of approximately twelve thousand Confederate soldiers who had died in the Richmond hospitals, whether by disease or war wounds. One of the first commemorations instituted was a Memorial Day, and soon adopted by other associations in the South.

The Association’s primary objective was to care for and prevent the neglect of the graves of approximately twelve thousand Confederate soldiers who had died in the Richmond hospitals, whether by disease or war wounds. One of the first commemorations instituted was a Memorial Day, and soon adopted by other associations in the South.

PLEASE NOTE: This article has been removed from the web site, but will be featured in the March-April 2020 issue of Digging History Magazine. It will be updated, complete with footnotes and sources as part of an extensive article entitled “Making Room for More: The Rural Cemetery Movement.”

I invite you to check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). We now have a special “trial” subscription. Purchase a trial one-year subscription with absolutely no obligation to re-subscribe. Check it out here.

Thanks for stopping by!

Surname Saturday: Harpending

It appears the first Harpending in America immigrated from Neuenhaus, Netherlands and his name was Gerrit Hargerinck. Gerritt arrived in America with his two sons in June of 1662 on the immigrant ship Hope. Other iterations of the surname were perhaps Harbendinck and Hargerinck and finally Harpending. At least one son of Gerrit’s, Johannes, had a son named John Harpending, so I assume that might have been the first usage of the Harpending surname. A few stories of some of the early Harpending family members follow.

John Harpending, according to “A History of American Manufactures, From 1608 to 1860″, was a “worthy citizen” who “by assiduous industry in his trade of tanner and shoemaker, had acquired a respectable fortune, and whose moral and religious character procured him the highest esteem.” Harpending, along with other businessmen and trademen, purchased a large tract of land that was later donated to the North Dutch Church.

John married Leah Cossart in 1716 and one of his children, Hendrik, was born around 1720 in either New York or Somerset, New Jersey. Hendrik followed in father John’s footsteps and excelled as a tanner and shoemaker. He married Mary Coons in 1742 and their son Peter not only served in the Revolutionary War it appears that he served directly under George Washington’s command at the Battle of Monmouth (New Jersey).

John married Leah Cossart in 1716 and one of his children, Hendrik, was born around 1720 in either New York or Somerset, New Jersey. Hendrik followed in father John’s footsteps and excelled as a tanner and shoemaker. He married Mary Coons in 1742 and their son Peter not only served in the Revolutionary War it appears that he served directly under George Washington’s command at the Battle of Monmouth (New Jersey).

Peter was a fiery patriot – he and fellow patriots of Somerset, New Jersey were labeled “arch-traitors” by British General William Howe, according to the Baker Family history blog. Peter operated a tavern and after the Declaration of Independence had been signed, a copy of it was read in his establishment to raucous cheers. According to the Baker Family site, Peter was a member of the Bound Brook Presbyterian Church’s “Radicals” – insistent on complete freedom from tyrannical British rule. Peter lived a good and long life, dying at the age of ninety-six in 1840.

In 1839 Asbury Harpending, Jr. was born to Asbury and Ann W. (Clark) Harpending. One family ancestry blog suggests that Peter and Asbury shared a common ancestor, Gerrit Hargerinck (Peter’s grandson was named Asbury, but this doesn’t appear to be the same person, however). According to Asbury, Jr., his father was one of the largest landowners in Kentucky. Young Asbury ran away from home to join General William Walker on an expedition to Nicaragua, but in 1855 his father sent him away to California where he accumulated a small fortune in the gold mining business.

Asbury Harpending, along with another Kentuckian, sought to halt California gold shipments to the United States Treasury and did his best to convince California to secede from the Union and join the Confederacy. Harpending was captured and detained at Fort Alcatraz to await trial. He was later found guilty of treason and served four months in a San Francisco jail, but in 1863 Abraham Lincoln pardoned him under the General Amnesty Act of 1863.

Asbury continued to build his gold mining business and helped found the company that sprung up as a result of what is now called The Great Diamond Hoax of 1872. He returned to Kentucky and built a $65,000 mansion to escape the embarrassing scandal. He left again in 1876 and until his death in 1923 he continued to pursue interests in California and the New York stock market.

While the early Harpending family appeared to have been upstanding, industrious and patriotic, it’s not clear that Asbury Harpending, Jr. was entirely cut from the same cloth. He was very successful but his dealings came into question when he became embroiled in the diamond hoax. John P. Young, in his book “San Francisco: A History of the Pacific Coast Metropolis” calls Harpending a “scamp”, so I’m sure he found it very difficult over the remaining years of his life to avoid his name being associated with the scandal.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Far-Out Friday: The Great Diamond Hoax of 1872

This story, without a doubt, has to be one of the most cunning and crafty hoaxes ever perpetrated on a group of learned men which included bankers, financiers and mining engineers. It reads more like a Hollywood script than actual fact, but it’s all true and quite fascinating how it was pulled off.

In February of 1872, Philip Arnold and John Slack strolled into the Bank of California in downtown San Francisco carrying a canvas bag and purported themselves to be prospectors who wanted to deposit their treasures in the bank’s vaults. The cashier demanded to see the contents of the bag and when the bag was opened discovered hundreds of uncut diamonds, sapphires, emeralds and rubies. The bank’s founder, William Ralston, was called into check out the deposit — intrigued, he wanted to know more.

In February of 1872, Philip Arnold and John Slack strolled into the Bank of California in downtown San Francisco carrying a canvas bag and purported themselves to be prospectors who wanted to deposit their treasures in the bank’s vaults. The cashier demanded to see the contents of the bag and when the bag was opened discovered hundreds of uncut diamonds, sapphires, emeralds and rubies. The bank’s founder, William Ralston, was called into check out the deposit — intrigued, he wanted to know more.

This article is no longer available here. It has been updated and enhanced for the September-October 2019 issue of Digging History Magazine, on sale here.

Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? That’s easy if you have a minute or two. Here are the options (choose one):

- Scroll up to the upper right-hand corner of this page, provide your email to subscribe to the blog and a free issue will soon be on its way to your inbox.

- A free article index of issues is available in the magazine store, providing a brief synopsis of every article published in 2018. Note: You will have to create an account to obtain the free index (don’t worry — it’s easy!).

- Contact me directly and request either a free issue and/or the free article index. Happy to provide!

Thanks for stopping by!

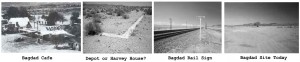

Off the Map: Ghost Towns of the Mother Road – Bagdad, California

The story goes that this Route 66 ghost town got its name in 1883 when the Southern Pacific Railroad named the station after Baghdad, Iraq (sans the “h”) because of its similar inhospitable climate. Curiously, the railroad named two other nearby towns “Siberia” and “Klondike”. A post office was added in 1889 and at one point the town bustled with activity, boasting a telegraph office, hotels, mercantile, a school and library, and a Harvey House restaurant.

The story goes that this Route 66 ghost town got its name in 1883 when the Southern Pacific Railroad named the station after Baghdad, Iraq (sans the “h”) because of its similar inhospitable climate. Curiously, the railroad named two other nearby towns “Siberia” and “Klondike”. A post office was added in 1889 and at one point the town bustled with activity, boasting a telegraph office, hotels, mercantile, a school and library, and a Harvey House restaurant.

Bagdad was an important stop along the train route since Ash Hill Grade heading northwest out of the town was quite a pull for westbound trains. Water was brought in from nearby Newberry Springs daily in 20-car trains. The Bagdad stop also provided coal and fuel oil, and during the 1900-1910 mining boom it was the station used to ship out product from the Orange Blossom and War Eagle mines. At its zenith, the town of Bagdad probably had close to 600 residents.

When mining in the area played out, the town began to decline. A fire in 1918 destroyed quite a few of the wooden buildings in town. In 1923 the post office was closed and in 1937 the library closed. In the 1940’s the depot, a few homes, the now famous Bagdad Café, a gas station and some cabins for Route 66 travelers remained. Former residents of Bagdad reminisce about the good old days when the Bagdad Café was the only place for miles around to have a juke box and dance floor, so it was known to be a lively place back in the day.

When mining in the area played out, the town began to decline. A fire in 1918 destroyed quite a few of the wooden buildings in town. In 1923 the post office was closed and in 1937 the library closed. In the 1940’s the depot, a few homes, the now famous Bagdad Café, a gas station and some cabins for Route 66 travelers remained. Former residents of Bagdad reminisce about the good old days when the Bagdad Café was the only place for miles around to have a juke box and dance floor, so it was known to be a lively place back in the day.

Of course, the Bagdad Café was the inspiration for the 1988 movie of the same name, although the film was shot at the Sidewinder Café in Newberry Springs (there is now a Bagdad Café in Newberry Springs). Even though Bagdad had ceased to be a thriving town long before, in 1972 Interstate 40 by-passed the town altogether – even the Bagdad Café closed its doors.

These days one might find a few pieces of junk or remnants of a time long gone by – there is a cemetery but most graves are unmarked. It is said that approximately fifty Chinese railroad workers were felled by cholera, I would presume in the 1880’s. One other interesting fact about Bagdad – true to its name and reputation as being inhospitable – from October 3, 1912 to November 8, 1914, the town of Bagdad was known as the driest place ever in the United States – 767 days without a drop of rain.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Ghost Town Wednesday: Christmas, Arizona

The first mining claim was filed in 1878 in Gila County, Arizona and another one was filed in 1882, but both were invalidated in 1884 when it was found the claims were located within the San Carlos Apache Indian Reservation.

Enterprising miner George B. Chittenden lobbied Congress to change the reservation boundaries and on December 22, 1902 President Theodore Roosevelt signed an executive order reverting the land back to the public domain. Chittenden and N.H. Mellor immediately staked their claims on Christmas morning – thus the name of both the mine and the town. According to an Arizona Republic article, the two men stated, “We filled our stockings and named the place Christmas in honor of the day.”

This article is no longer available for free at this site. It was re-written complete with footnotes and sources and has been published in the December 2018 issue of Digging History Magazine. Should you prefer to purchase the article only, contact me for more information.

This article is no longer available for free at this site. It was re-written complete with footnotes and sources and has been published in the December 2018 issue of Digging History Magazine. Should you prefer to purchase the article only, contact me for more information.

I invite you to check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Feudin’ and Fightin’ Friday: Fence Cutting War (Don’t Fence Me Out)

The first use of barbed wire in Texas occurred in 1857 when immigrant John Grinninger ran homemade barbed wire along the top of fencing around his garden. The first United States Patent for barbed wire was issued in 1867.

The first use of barbed wire in Texas occurred in 1857 when immigrant John Grinninger ran homemade barbed wire along the top of fencing around his garden. The first United States Patent for barbed wire was issued in 1867.

Barbed wire began to be mass-produced after another patent was granted to Joseph Farwell Glidden of Illinois. Prime range land consisted of treeless stretches of prairie. Without significant supplies of timber to build fences, barbed wire became more popular as cattle ranchers sought effective means to control access to their land.

The XIT Ranch in the Texas Panhandle put up some six thousand miles of barbed wire and farmers would fence their grain fields as well. Sometimes the fencing crossed roads and interfered with delivery of the mail — even public land was fenced. Open range cattle ranchers became alarmed when access was cut off to prime grazing pastures and water.

The XIT Ranch in the Texas Panhandle put up some six thousand miles of barbed wire and farmers would fence their grain fields as well. Sometimes the fencing crossed roads and interfered with delivery of the mail — even public land was fenced. Open range cattle ranchers became alarmed when access was cut off to prime grazing pastures and water.

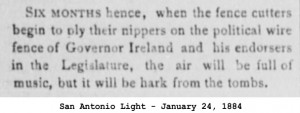

The situation reached a crucial stage in 1883, a year of severe drought. News and opinion articles across the state highlighted the work of the “nippers” as they were called. According to Texas, A Modern History: Revised Edition (p. 92):

Nipping became indiscriminate and was often done secretly at night by armed groups calling themselves Owls, Javelinas, or Blue Devils. They threatened fencers and burned pastures. Three people died and damage was estimated at $20 million.

The Galveston News reported that nippers had destroyed fencing around a 700 acre property on Tehuacana Creek near Waco. A threatening note regarding a pond on private property was left behind:

The Galveston News reported that nippers had destroyed fencing around a 700 acre property on Tehuacana Creek near Waco. A threatening note regarding a pond on private property was left behind:

You are ordered not to fence in the Jones tank, as it is a public tank and is the only water there is for stock on this range. Until people can have time to build tanks and catch water, this should not be fenced. No good man will undertake to watch this fence, for the Owls will catch him. There is no more grass on this range than the stock can eat this year.

While newspapers were vocal in their condemnation of nipping, state politicians were mostly silent on the issue. Meanwhile, however, Governor John Ireland was being urged to intervene. One of the strongest lobbyists for intervention was a woman by the name of Mabel Doss Day.

In 1881 her husband had died after his horse fell during a stampede, leaving his widow with a debt-ridden ranch. She successfully worked to put the ranch company back on solid financial ground and in 1883 her land was the largest fenced ranch in Texas. Mabel became a victim of the fence cutters and lobbied in Austin for a law to make it felonious to cut fencing. A special legislative session was called by Governor Ireland to meet on January 8, 1884 to craft a solution.

After weeks of debate, the legislature passed a bill that made the crime of fence-cutting punishable by one to five years in state prison, while the crime of burning a pasture was punishable by two to five years in prison. It became a misdemeanor to willfully and knowingly fence public lands or someone else’s property without consent. Offenders had six months to comply with the new law, and for fences that crossed public roads, gates were required every three miles.

The law apparently wasn’t necessarily popular state-wide:

And, the law didn’t necessarily solve the problem either. It appears that the crime of “nipping” continued for years (click to enlarge):

Drought years would heighten nipping activity even after the law’s passage, until in 1888 local law enforcement in Navarro County called on the Texas Rangers to intervene. Sergeant Ira Aten (who would later be instrumental in settling the Jaybird-Woodpecker War) and Jim King were dispatched to the area. Disguised, the two Rangers secured jobs picking cotton and kept their eyes and ears open, soon discovering who the cutters were. Aten placed dynamite charges along fence lines so that when the wire was cut an explosion would occur. While the Adjutant General did not approve and ordered the practice to cease, fence cutting was curbed significantly and eventually the Fence Cutting War subsided.

Route 66 Ghost Towns: Ludlow, California

Route 66 – it was called “The Mother Road” – stretching from Chicago, Illinois to Santa Monica, California. The 2448-mile road opened in 1926 and wasn’t completely paved until 1937, crossing eight states and three time zones. The Dust Bowl refugees of John Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath traveled Route 66, songs were written about it (“Get Your Kicks on Route 66″), and a 1960’s television series was inspired by this iconic road.

Route 66 – it was called “The Mother Road” – stretching from Chicago, Illinois to Santa Monica, California. The 2448-mile road opened in 1926 and wasn’t completely paved until 1937, crossing eight states and three time zones. The Dust Bowl refugees of John Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath traveled Route 66, songs were written about it (“Get Your Kicks on Route 66″), and a 1960’s television series was inspired by this iconic road.

Towns that had sprung up (or revived when Route 66 opened) were deserted when Route 66 began to gradually be replaced by more modern four-plus-lane highways, which became increasingly necessary as America became more prosperous and mobile. In some towns there might be a building or gas station two and maybe a handful of residents, but in many cases little else remains except perhaps shells of long abandoned buildings.

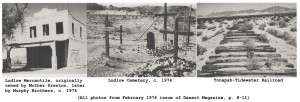

Ludlow, California

It is said that the town of Ludlow died not once but twice, although today there are still a few remaining residents. Ludlow was founded in 1882 as a water stop on the Atlantic and Pacific Railroad (later taken over by the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad in 1897) and named after rail car repairman William B. Ludlow.

The town took off once gold was discovered in the nearby Bagdad-Chase Mine in 1900. The first samples milled from the mine yielded about $17,000 per one thousand tons of ore so mine production was stepped up. However, there wasn’t enough water at the actual mine to process the ore (Ludlow was famously short on water), so it had to be shipped out via the Ludlow-Southern Railroad, beginning in 1903. From Ludlow the ore was transferred to the mill at Barstow.

The town took off once gold was discovered in the nearby Bagdad-Chase Mine in 1900. The first samples milled from the mine yielded about $17,000 per one thousand tons of ore so mine production was stepped up. However, there wasn’t enough water at the actual mine to process the ore (Ludlow was famously short on water), so it had to be shipped out via the Ludlow-Southern Railroad, beginning in 1903. From Ludlow the ore was transferred to the mill at Barstow.

The superintendent of the Bagdad-Chase Mine declared the company town of Rochester (later named Steadman) as a “closed camp” – no women and no liquor! This gave Ludlow entrepreneurs a boost as miners came to town on Saturday night looking for entertainment. Most of the town of Ludlow was owned by the Murphy Brothers. Another entrepreneur, known as Mother Preston, owned several buildings in town, including a store, hotel, boarding house, saloon, café, pool hall and three homes. She was known to be a good businesswoman and an expert poker player – when she sold out to the Murphy Brothers, she retired to France.

When borax was discovered in the area, Francis Marion “Borax” Smith built a railroad which ran from Ludlow to Beatty, Nevada. The railroad, the Tonopah and Tidewater Railroad, was 169 miles long. Having three railroads running through Ludlow was a boon to the town – as long as the mines were operational – but as the saying goes “nothing lasts forever.”

In 1927-1928 the Pacific Coast Borax Company began shutting down operations so the need for the T & T Railroad declined, with the coming Depression hastening its complete demise. The railroad line ceased operations in 1933 and by 1943 the tracks had been torn up. The Ludlow-Southern Railroad had ceased operations in 1916, but apparently not because gold mining 0perations ceased. According to author David Myrick (Railroads of Nevada and Eastern California), from 1880 to 1970 the Bagdad-Chase mine produced half of all the gold mined in San Bernardino County.

After the two railroad lines ceased operations, Ludlow began to decline. Ludlow was revived when Route 66 opened and for awhile it thrived again. But, when I-40 was built and the town was by-passed, Ludlow died again. Today, remains of the first and second ghost town of Ludlow still stand: a shell of the Ludlow Mercantile Company (originally Mother Preston’s and then the Murphy Brothers), railroad tracks, a neglected and deteriorating cemetery and the old Ludlow Café.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!