Surname Saturday: Frisbie

Today’s surname is easy to identify as to its origins. After the Norman Conquest in 1066 the name appeared as a locational name. The family lived in Leicestershire in a town called “Frisby” (no longer in existence). There is a village in Leicestershire today called “Frisby on the Wreake”, however.

According to one source, there are several towns in England called “Frisby” and all derive from “frisir,” an Old Norman word which meant someone from Frisia or Friesland. The earliest instance of this surname appeared in the Domesday Book of 1086 as “Frisebi” (without surname). In 1198, another “Frisebi,” again without surname, lived in Leicestershire. For the Yorkshire Poll Tax of 1379, the name “Robertus de Frysby” was recorded and William de Frisseby was the rector of Filby, County York in 1412.

Spelling variations include: Frisbie, Frisby, Frisbee, Frisebie, Frisebye, Friseby and others. At the time of the Revolutionary War there were as many as fifteen spelling variations of this surname.

Richard Frisbie

Records and family histories appear to indicate that Richard Frisbie immigrated to Virginia from England in 1620. It is believed that Richard was born in 1591 in St. James, Clerkenwell, London, England. Most family genealogists believe that Richard married Margaret Emerson on November 30, 1618. In 1619 their first child Mary was born and christened on November 7 in St. James. It seems a bit uncertain as to when their next child, Edward, was born. Some say he was born in 1620 in England and others believe he was born in Virginia in 1621 after Richard and Margaret immigrated there.

What is known is that Richard departed in February of 1620 on board the Jonathan which carried two hundred passengers. The ship reached Jamestown on May 27, traveling fourteen weeks, losing twenty-five passengers and four crew members. One of the casualties appears to have been young Mary (or perhaps she died soon after arrival).

Some family historians speculate that perhaps Richard came over as a half-share tenant of the Virginia Company of London. If so, the terms would have included the Company paying the cost of his passage. In exchange he would have agreed to work for them for a certain number of years and during that time would receive half of what he produced. The crop he raised was likely tobacco.

Some family historians speculate that perhaps Richard came over as a half-share tenant of the Virginia Company of London. If so, the terms would have included the Company paying the cost of his passage. In exchange he would have agreed to work for them for a certain number of years and during that time would receive half of what he produced. The crop he raised was likely tobacco.

Seven years was a common term for an indenture agreement at that time. That would have meant he was bound to the Company until 1627. However, in 1624 the Virginia Company’s charter was withdrawn by King James and placed directly under royal commission. Some speculate that his indenture agreement may have been voided as a result because Richard returned to London in 1625. At this time it appears that he and Margaret had at least two children, Edward and Ann.

Apparently their timing for returning to England was not good as there was a plague epidemic which would sicken Ann. She was buried in August of 1625. Another son, Richard, was born in 1626 and died in 1629. In 1628 twins Zechariah and Henry were born and both died in 1629 (although not the same date). Peter was born in 1630, George in 1633 (died in infancy) and Jane in 1634. It is believed that the family left to return to America in 1635 (Peter, however, was left behind in England for some reason).

There don’t seem to be any more records of Richard, Margaret or Jane. Some speculate they died soon after returning to Virginia or possibly died at sea, leaving fourteen year-old Edward as the family’s sole survivor. Therefore, Edward Frisbie is considered the progenitor of all Frisbies born in America.

Edward Frisbie

Family historians record that Edward, after being banished from the Virginia Colony for his Puritan beliefs, removed to the New Haven Colony in 1644, settling in Branford, Connecticut. Edward married Hannah Rose (or Hannah Rose Culpepper) in Branford in 1649. Eleven children were born to their marriage, including a set of twins:

John – 1650

Edward – 1652

Samuel – 1654

Benoni – 1656

Abigail – 1657

Jonathan – 1659

Josiah – 1661

Caleb – 1666

Hannah – 1669

Silence – 1672

Ebenezer – 1672

All their children lived to adulthood and died in Branford. Some historians have speculated that Edward had more than one wife, but others indicate that Hannah lived until 1690. He was apparently a wealthy landowner since in his will there are references to several tracts of land in Branford. His estate was inventoried on May 26, 1690 – his surname signed as “Frisbye”.

Many of Edward’s Connecticut descendants served in the Revolutionary War. As noted above there were several spelling variations, including: Frisby, Frissbee, Fruisbie, Frisbee, Fresbee, Fresbie, Frisbe, Frisbea, Frisbees, Frisbies and Frisbey.

William Russell and Joseph P. Frisbie

No article about the Frisbie family would be complete without the story of how the round disk known as the “Frisbee” came to be. Historians trace it back to 1871 when William Russell Frisbie moved to Bridgeport from Branford, Connecticut (he, obviously a descendant of Edward). His father Russell operated a grist mill in Bridgeport and William took a job managing the local branch of the Olds Baking Company.

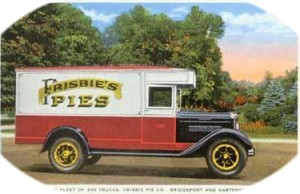

William later purchased the bakery and changed the name to “Frisbie Pie Company”. Upon his death in 1903, his son Joseph took over management of the company. Under Joseph’s leadership the company grew from six routes to two hundred fifty, opening stores in Hartford, Poughkeepsie, New York and Providence, Rhode Island. In his book What’s in a Name?, Philip Dodd describes Joseph’s inventions and management practices:

William later purchased the bakery and changed the name to “Frisbie Pie Company”. Upon his death in 1903, his son Joseph took over management of the company. Under Joseph’s leadership the company grew from six routes to two hundred fifty, opening stores in Hartford, Poughkeepsie, New York and Providence, Rhode Island. In his book What’s in a Name?, Philip Dodd describes Joseph’s inventions and management practices:

The family house became the site of a factory with baking rooms, delivery bays and new machinery, much of it invented by Joseph P., who preferred to custom-design and build his own equipment: a pie rimmer using the principle of the potter’s wheel, meat tenderers, a cruster that could process eighty pies a minute. Since there was no electricity for the bakery, he had a power plant constructed in the basement.

He had high standards of cleanliness and hygiene, a trait learned from his father. The deliverymen in their fleet of trucks and the factory staff wore snappy uniforms, the salesmen crisp jackets with bow ties and peaked caps. They had good wares to sell, up to thirty varieties of individual and family-size pies, delivered hot to a network of grocery stores.

Production levels steadily increased and by 1940 the bakery was churning out two hundred thousand pies a day, employing almost eight hundred workers. Joseph had a heart attack in the 1930’s and in 1941 he passed away at the age of sixty-three. His widow Marion ran the business for several years until it was sold in 1958.

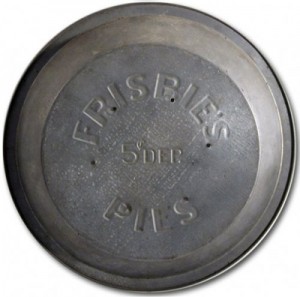

One historian believes that the company’s truck drivers were the first to toss Frisbie Pie tins on the loading docks when they had down time. The tins were engraved with “Frisbie’s Pies” and had six small holes, centered in a star pattern, so that the tin would “hum” as it flew. It is believed that the “sport” of Frisbie migrated to several Eastern colleges, perhaps first at Yale. Students would shout “Frisbie!” to warn of the incoming pie tin – a new sport called “Frisbie-ing” had been invented.

Sometime in the mid-1940’s two men, Walter “Fred” Morrison and Warren Franscioni, saw possibilities in marketing a plastic flying disk. Their first version was called “The Flyin’ Saucer” and wildly popular cartoon character Lil’ Abner was used to sell it. After their efforts failed, Morrison launched his own version in 1955, calling it the “Pluto Platter Flying Saucer.”

That version caught the eye of executives at Wham-O and, as the old saying goes, the rest is history. Wham-O changed the spelling and on January 13, 1957 the Frisbee was introduced to the world. Since 1957 over two hundred million Frisbees have been sold – all attributable to a Bridgeport, Connecticut pie company run by the Frisbie family which could, of course, be traced all the way back to immigrant Edward Frisbie.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

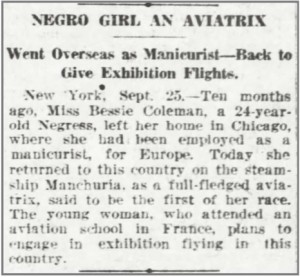

Feisty Females: Bessie Coleman

Elizabeth “Bessie” Coleman was born on January 26, 1892 to parents George and Susan Coleman, she being the tenth of their thirteen children. George Coleman was part African American and part Cherokee, a sharecropper in Atlanta, Texas which had been settled by former Georgia residents. While there were opportunities to make money in the local industries (railroads, oil, lumber), the Coleman family struggled. George moved his family to Waxahachie in 1894, hoping to do better for himself and his family.

Elizabeth “Bessie” Coleman was born on January 26, 1892 to parents George and Susan Coleman, she being the tenth of their thirteen children. George Coleman was part African American and part Cherokee, a sharecropper in Atlanta, Texas which had been settled by former Georgia residents. While there were opportunities to make money in the local industries (railroads, oil, lumber), the Coleman family struggled. George moved his family to Waxahachie in 1894, hoping to do better for himself and his family.

George purchased a quarter-acre plot of land and built a small three-room house in the black section of Waxahachie. By all accounts, Bessie’s early childhood was a happy one. She began school at the age of six and walked four miles each day to the all-black school where she excelled, especially in math.

In 1901, George Coleman left his family and headed to Indian Territory (Oklahoma) to pursue better opportunities, citing racial barriers too difficult to overcome in Texas. Susan, however, refused to accompany him and was left with four girls under the age of nine after her older sons also left home. Susan obtained employment as a cook and housekeeper. The family she worked for allowed her to live in her own home and also provided clothing for the girls.

In 1901, George Coleman left his family and headed to Indian Territory (Oklahoma) to pursue better opportunities, citing racial barriers too difficult to overcome in Texas. Susan, however, refused to accompany him and was left with four girls under the age of nine after her older sons also left home. Susan obtained employment as a cook and housekeeper. The family she worked for allowed her to live in her own home and also provided clothing for the girls.

Their routine, however, was disrupted every year when the Coleman family participated in the cotton harvest. Bessie continued to excel in school and when she had completed the eighth grade (probably all the primary education available to her at the time), she saved her money and entered the Colored Agricultural and Normal University in Langston, Oklahoma in 1910. Her money was exhausted after one term and she returned to Waxahachie where she worked as a laundress. By 1915 Bessie Coleman wanted more out of life so she headed to Chicago where her brother Walter lived.

She found work as a manicurist in the White Sox Barbershop and Susan and her remaining children joined her in 1918. Her brothers came home after World War I with war stories, including those of French female pilots. In 1919 the worst race riot in history took place in Chicago and Bessie would soon conclude she wanted something more out of life. Her ambition was to become a pilot like the French women her brothers boasted about.

At the age of twenty-seven she began pursuing a career in aviation, but first she had to find someone willing to train her. However, for a black woman those opportunities just didn’t exist in America at that time. Still determined to pursue her dream of becoming a pilot she obtained funding and a passport and headed to France in November of 1920.

The course, taught at Ecole d’Aviation des Freres Caudon, was normally ten months in length – Bessie completed it in seven. On June 15, 1921 Bessie Coleman received her pilot’s license from the Federation Aeronautique Internationale. She was the first black person, male or female, ever to do so and the only woman of the sixty-two candidates that year eligible for licensing.

Upon her return to America in September she received widespread press coverage:

At that time in history flight exhibitions were a popular form of entertainment in the United States. Lacking skills to perform as a stunt pilot at those shows, Bessie returned to France for more training. She returned to the States in August of 1922, and on September 3 she was billed as “the world’s greatest woman flier” at an event held at Curtiss Field in New York City. Six weeks later she returned to Chicago to enthrall a crowd at the Checkerboard Airdome (now Midway Airport).

She continued to work as a stunt flier, but still had ambition to do more. Briefly she considered a movie career and traveled to California to earn money to purchase a plane of her own. She crashed the plane on February 22, 1923 and returned to Chicago to pursue her ultimate goal of opening her own flight school. It would take awhile to accomplish since along the way she had to overcome the barriers of both race and gender.

Back in Texas she began appearing in towns big and small across the state to give lectures and perform exhibitions. One stipulation she always insisted upon for her exhibitions – everyone, regardless of race, was to be admitted without being segregated. She was able to make a down payment on another plane and then continued lecturing in Georgia and Florida. Still planning to open a flight school, she also opened a beauty shop in Orlando to earn more money to put towards the flight school. Because she was still making payments on her plane, she borrowed planes and continued to perform exhibitions, even occasionally parachuting.

By spring of 1926 she had finally made the final payment on her plane and arranged to have it flown to Jacksonville, Florida where she would be performing on May 1. On April 30, Bessie and her mechanic took the plane up for a test flight. The mechanic was piloting and suddenly lost control of the plane. Bessie, who was not wearing her seat belt, was thrown from the open cockpit, plummeting two thousand feet to her death. The plane crashed and burned, killing the mechanic as well. It was later discovered that a wrench had accidentally slid into the gearbox, jamming it.

Bessie Coleman died on April 30, 1926 at the age of thirty-four. Her body was returned to Chicago for burial and several thousand mourners paid their respects. She would later have buildings and streets named in her honor. In 1995 the United States Postal Service honored her with a commemorative stamp. The accompanying resolution stated, “Bessie Coleman continues to inspire untold thousands even millions of young persons with her sense of adventure, her positive attitude, and her determination to succeed.”

Earlier this year I wrote an article about “Feisty Female” Cornelia Clark Fort, another pioneering aviator. If you haven’t yet read that article, check it out here. Also, Fannie Flagg’s latest book is a great read and loosely based on Cornelia’s story.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Wild West Wednesday: Buckshot Roberts and the Gun Battle at Blazer’s Mill

This gun battle at Blazer’s Mill, located on the Rio Tularosa, is considered part of the Lincoln County War of 1878. The most famous participant of that war was, of course, William H. Bonney, a.k.a. “Billy the Kid.” Billy and his fellow posse members called themselves the “Regulators” and were led by Dick Brewer. Their “opponents” were the Murphy-Dolan faction who aligned themselves with Lincoln County Sheriff William Brady.

This gun battle at Blazer’s Mill, located on the Rio Tularosa, is considered part of the Lincoln County War of 1878. The most famous participant of that war was, of course, William H. Bonney, a.k.a. “Billy the Kid.” Billy and his fellow posse members called themselves the “Regulators” and were led by Dick Brewer. Their “opponents” were the Murphy-Dolan faction who aligned themselves with Lincoln County Sheriff William Brady.

The Regulators were more or less the “extra-legal” force for the Tunstall-McSween faction who supported the town constable Dick Brewer (the Regulators’ leader). Tensions between the two factions had been brewing for awhile but erupted into a full-scale county war early in 1878. On February 18, John Tunstall was murdered, which precipitated the organization of Brewer’s posse.

Sheriff Brady was later killed on April 1. These two events set the stage for the gun battle at Blazer’s Mill. Andrew L. “Buckshot” Roberts would be drawn into the war whether he wanted it or not because the Regulators thought he might have been involved in Tunstall’s murder.

The history of Andrew Roberts is, at best, sketchy. Many stories and theories abound as to his origins. Some believe he was from Texas, others believe he was born farther east. His grave stone has a marker indicating he fought as a Confederate in the Civil War. Another theory has him joining the Texas Rangers after the war and fighting Indians – yet another story has him later doing battle against the Texas Rangers. Some historians suggest that he was once a buffalo hunter and rode with William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody.

The history of Andrew Roberts is, at best, sketchy. Many stories and theories abound as to his origins. Some believe he was from Texas, others believe he was born farther east. His grave stone has a marker indicating he fought as a Confederate in the Civil War. Another theory has him joining the Texas Rangers after the war and fighting Indians – yet another story has him later doing battle against the Texas Rangers. Some historians suggest that he was once a buffalo hunter and rode with William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody.

Whatever his true history, along the way he earned the moniker of “Buckshot” after he was shot up so bad his right arm was crippled. After that he wasn’t able to lift a rifle to his shoulder – he shot strictly from the hip. At some point, perhaps wanting to settle down with a more peaceful existence, he bought a little ranch near Ruidoso. While he officially took no sides in the Lincoln County Wars, it was generally believed that he aligned himself with the Dolan-Murphy faction.

Noted author and western historian Emerson Hough wrote about Roberts in his book The Story of the Outlaw: A Study of the Western Desperado:

When the Lincoln County War broke out, he was recognized as a friend of Major Murphy, one of the local faction leaders; but when the fighting men curtly told him it was about time for him to choose his side, he as curtly replied that he intended to take neither side; that he had seen fighting enough in his time, and would fight no man’s battle for him. This for the time and place was treason, and punishable with death. Roberts’ friends told him that Billy the Kid and Dick Brewer intended to kill him, and advised him to leave the country.

Roberts decided to do just that as he sold his property and prepared to leave. Again there are various theories as to why Roberts rode into Blazer’s Mill on April 4 (just three days after Sheriff Brady had been murdered). Hough mentions three theories or rumors: that he went to meet a friend who had been badly wounded; he went to confront Major Godfroy who he’d had a disagreement with; or he was headed there to kill none other than Billy the Kid. Hough thought it more likely he was there to visit his friend.

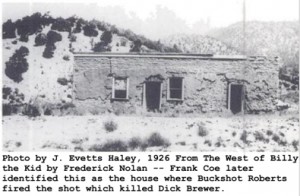

Yet another story, which might be the most plausible of all, was that he was there checking to see if payment for his land sale had arrived in the mail. Again, whatever the actual facts, it appears he unknowingly rode in to find the Regulators were also there. One member of the Regulators, Frank Coe, asked Roberts to give up his weapons, which Roberts refused to do. Meanwhile the rest of the Regulators had retreated behind a house.

One eyewitness said that suddenly the rest of the gang came from behind the house and began firing at Roberts. Rather than retreat inside the house, Roberts began firing on the Regulators (twelve or thirteen men). Roberts shot Jack Middleton (although not mortally wounded), shot off George Coe’s finger, grazed another one or two and almost got off a shot at Billy the Kid, but instead his gun misfired.

Charlie Bowdre came around the house next and Roberts fired at him, striking his belt and cutting it off. Bowdre almost simultaneously fired at Roberts and wounded him – although later other Regulators would claim they actually shot Roberts. Roberts now retreated back into the house. Having run out of ammunition for his own rifle, he picked up another rifle and pulled a mattress to the floor and laid upon it near the open window at the front of the house.

By this time, everyone had retreated, but Dick Brewer decided to take matters into his own hands. He approached the house by crossing the river over a foot bridge. When he found a strategic spot from which to take aim (about 125 yards west of the house), he fired into the house. While his shot did nothing but scatter bits of adobe, it gave Roberts a bead on where his target was hiding.

Even though Brewer’s eyes were barely visible above the pile of logs where he was hiding, Roberts, himself severely wounded, fired and struck Dick Brewer in the eye – blowing off the top of his head. With Brewer laying dead, Billy the Kid became the de facto leader and ordered his men to retreat. It was apparent to them that their scrappy opponent would kill them all if he had the chance. Billy the Kid would remember the gun battle by remarking, “Yes sir, he licked our crowd to a finish.”

Buckshot Roberts did indeed hold his own against the Regulators, but on April 5 he died after attempts to save his life failed. Before he died he was so desperately in pain that two men had to hold him down. Eyewitness Johnny Patten claimed that he built a coffin in the shape of a big “V” so that both Roberts and Brewer could be buried side by side. “We just put them both in together,” said Patten, “and there they lie today grim grave-company.”

When Emerson Hough visited the battle site in 1905 he verified and measured the distances reported. It was indeed a 125-yard downhill shot made by Roberts which killed Dick Brewer. For someone with such great odds against him, not to mention his inability to lift a rifle to shoulder-level, Buckshot Roberts put up one heck of a fight. According to one source, it was later proven that he had nothing to do with Tunstall’s murder.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Mothers of Invention: Sarah Mather and Martha Coston (Also Making Civil War Naval History)

The subjects of today’s article were not only “mothers of invention” but also made a bit of naval history as well, contributing to the Union’s cause during the Civil War.

The subjects of today’s article were not only “mothers of invention” but also made a bit of naval history as well, contributing to the Union’s cause during the Civil War.

Sarah Mather

Unfortunately, for history’s sake, little is known about inventor Sarah Mather. One source believes her to have been married with at least one daughter. There don’t appear to be any records of other inventions by Sarah Mather (except an improvement on the first). However, her submarine telescope was an important naval innovation.

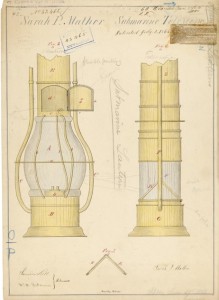

On April 16, 1845, Brooklynite Sarah Mather was granted a patent (US Patent No. 3995) for an invention she called a “submarine telescope” – an “Apparatus for Examining Objects Under the Surface of the Water”.

On April 16, 1845, Brooklynite Sarah Mather was granted a patent (US Patent No. 3995) for an invention she called a “submarine telescope” – an “Apparatus for Examining Objects Under the Surface of the Water”.

The nature of my invention consists in constructing a tube with a lamp attached to one end thereof so to be sunk in the water to illuminate objects therein, and a telescope to view said objects and make examinations under water. . . .

It will at once be obvious that the above named lamp and telescope can be used for various purposes, such as the examination of the hulls of vessels, to examine or discover objects under water, for fishing, blasting rocks to clear channels, for laying foundations or geological formations, the lamp being used for lighting the objects while inspected by the telescope.

Primarily, her invention was used to examine a ship’s hull without having to remove it from the water. On July 5, 1864 she was awarded US Patent No. 43465 for an “Improvement in Submarine Telescopes”. With the beginnings of submarine warfare during the Civil War, her invention was also useful in detecting Confederate underwater activity.

Martha Jane Hunt was born in Baltimore, Maryland in 1826. After her mother was widowed, her family moved to Philadelphia sometime in the 1830’s. By the age of fourteen, Martha, in her own words, was “unusually tall and mature in appearance for my age.” She attended school and studied hard. One summer day she was attending a picnic in the park and met nineteen year-old inventor Benjamin Coston.

His prowess as a skillful inventor was well-known in Philadelphia. He had been working on a “submarine boat or torpedo” which could operate underwater up to eight hours without resurfacing. The air needed to survive underwater was a chemical process which he had also invented. She was obviously impressed with his skills as an inventor, not to mention his handsome features. In her autobiography, A Signal Success, she remarked, “to tell the truth, I was a little too much in awe of his genius to be quite at my ease with him.”

They began to spend a great deal of time together, he assisting with her school work, especially in mathematics, grammar and history. As long as he remained in the city she excelled, but during his absences her grades suffered. She began to depend on him and, needless to say, she was falling in love with Mr. Coston, and he with her. Her mother was shocked to hear from Benjamin that he was in love with her “baby girl”, but agreed to allow their marriage when Martha reached the age of eighteen.

Benjamin’s work had caught the attention of Admiral Charles Stewart, a.k.a. “Old Ironsides”. The admiral urged Benjamin to join the navy and arranged a meeting with the Secretary of the Navy. Benjamin received an appointment as master in the service of the Navy at the Washington Navy Yard. Realizing that they would be separated for an extended time, and having grown so fond of each other, they decided to elope.

With her sister (Nellie) and Nellie’s fiancé Tom Blair as witnesses:

We proceeded at once to the house of a minister, unworthy of the gospel he preached, and willing for the sake of an extra fee to ask no embarrassing questions and agree to make no revelations. . . . and in a few moments it was over, and I, a sixteen-year-old girl, a wife.

Because of Benjamin’s assignment to the Washington Navy Yard (instead of a two-year scientific expedition at sea), the young couple relocated to Washington, D.C. After four years of marriage they had two young sons. Benjamin’s worked in a pyrotechnic laboratory where he developed and tested rocketry for the government. Although his work was well received, Benjamin and the Navy were at odds in regards to promotions and credit for his work. He resigned and accepted a position as president of Boston Gas Company.

The family continued to grow after they moved to Boston. After the birth of their fourth son, Benjamin was called to Washington on business. As he was returning, he became seriously ill and three months later died. Martha returned to Philadelphia to live with her mother, but not long afterwards her baby son Edward became ill and died as well.

The tragedies continued as her mother also died a short time later. Martha, always close to her mother, was devastated, remarking “I had lost both my anchor and my pilot, and was at the mercy of unknown seas.” As she was dealing with multiple tragedies, the family’s finances had not been tended to properly and Martha realized that her source of income from Benjamin’s business was depleted. At twenty-one she was penniless with three small children.

One rainy afternoon in November she began going through some of Benjamin’s papers, some of which consisted of his notes for unfinished inventions and chemical experiments while working with pyrotechnics for the Navy. She came upon a large envelope which contained a detailed plan for signals which could be used at night much like signal flags were used during the day. Each signal was numbered and a certain fire color assigned to each one, corresponding to colors used by signal flags during the day.

She began corresponding with Navy officials, trying to find someone interested in the perfection of Benjamin’s plans. Some of her husband’s naval co-workers assisted her efforts to develop flares for testing. The tests, unfortunately, were utter failures. In the meantime, tragedy struck again when her second son became ill and died – just as her initial communication efforts were rebuffed. Still, the Secretary of the Navy encouraged her to continue.

Martha pursued the task, giving over the care of her two remaining sons to friends so she could dedicate herself full-time to the project. It would take years of working with chemists to perfect the flares, as well as find a manufacturer. The task was arduous, but they finally were successful in developing a pure white and vivid red light. A third color was needed, however.

In August of 1858 Martha was in New York City attending the celebration of the first transatlantic telegraph cable being laid. A fireworks display gave her the idea that a pyrotechnics company might be able to help her develop the third color. She inquired with several firms, requesting either a blue or green color. They worked together for several weeks and finally in February of 1859, a naval review board gave her a favorable report. On April 5, 1859, Martha Coston was granted US Patent No. 23,536 for a pyrotechnic night signal and code system. Benjamin, however, was listed as the inventor and she as the administratix.

For the next two years, the Navy tested the new system around the world with satisfying results. The perfection and successful testing couldn’t have come at a better time. After Fort Sumter, Congress passed a funding bill and Martha and her partner immediately began production of the Coston signal flare – they sold one million flare signals during the Civil War. The signals were, of course, important tools to issue orders before and during battles. For the Navy, however, it allowed them to identify whether an approaching vessel was friend or foe, since the Union exclusively used the signals.

So successful were the Coston signal flares, David Dixon Porter, a Mississippi River squadron commander, would later write:

at night the signals can be so plainly read that mistakes are impossible, and a commander-in-chief can keep up a conversation with one of his vessels distant several miles, and say what is required almost as well as if he were talking to the captain in his cabin. This was the case in the Mississippi and also in the North Atlantic Squadron during the war, where we read hundreds of these signals (nay, thousands), which were frequently kept going all night long.

Martha continued to improve the device and in 1871 received a patent for a “Twist Ignition” device. Coston Signals were used on April 17, 1912, the fateful night when the Titanic sunk. Naval and Coast Guard services utilized the signals until marine radios came into usage in the 1930s.

Martha continued to improve the device and in 1871 received a patent for a “Twist Ignition” device. Coston Signals were used on April 17, 1912, the fateful night when the Titanic sunk. Naval and Coast Guard services utilized the signals until marine radios came into usage in the 1930s.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Surname Saturday: Nutting

The Nutting surname is Anglo-Saxon and derives from the Middle Ages English name of “Cnute” which became popular after a Dane by the name of “Cnut” became King of England in 1016. According to the Patronymica Britannica:

Ferguson derives this name and Nutt from Knut, or Canute, the Danish personal name; Knut was derived from a wen or tumour on his head. It is however worthy of remark, that the hazel, Anglo-Saxon hnut-beam, gave rise to several names of places, from some of which surnames have been derived, as Nutfleld, Nuthall, Nuthurst, Nutley, Nuthampstead. The names Nutter and Nuttman are also probably connected with this tree-signifying, perhaps, dealers in its fruit.

Another possibility as to origin is that the surname was derived from the Old English word “hnutu”, which meant brown. It could have been a nickname given to someone with a brown complexion since the English have an old saying “brown as a nut”. For instance, in A Study in Scarlet (Sherlock Holmes), one line reads: “Whatever have you been doing with yourself, Watson?” he asked in undisguised wonder, as we rattled through the crowded London streets. “You are as thin as a lath and as brown as a nut.”

Another possibility as to origin is that the surname was derived from the Old English word “hnutu”, which meant brown. It could have been a nickname given to someone with a brown complexion since the English have an old saying “brown as a nut”. For instance, in A Study in Scarlet (Sherlock Holmes), one line reads: “Whatever have you been doing with yourself, Watson?” he asked in undisguised wonder, as we rattled through the crowded London streets. “You are as thin as a lath and as brown as a nut.”

A 1379 Yorkshire poll tax record lists a “Willelmus Nutyng”. Other spelling variations include Nutt, Nutter, Nudd, Nuttman, Knutt, to name a few. John Nutting immigrated from England as John Winthrop’s land steward and is considered the progenitor of all Nuttings in America – his story follows.

John Nutting

Some believe that John Nutting was born sometime between 1620 and 1625 to parents John and Elizabeth Rawlings Nutting. There is, however, a theory that he may have been a child in 1618 since a copyhold deed found among (John) Winthrop papers read: “John Nutton (Nutting) a lifelong tenant of one moiety of the lands of Groton Manor”. The grantee named was John Nutton, Senior. This would imply that there was a John Nutton (Nutting), Jr., and therefore that he had been born prior to 1618.

One source believes that John Nutting (Junior) immigrated in 1639, although it seems unclear as to when exactly he made the voyage across the Atlantic. Nevertheless, the first solid reference to his presence in the Massachusetts Colony was the record of his marriage to Sarah Eggleton on August 28, 1650 in the town of Woburn. Before their fifth wedding anniversary, three children were born:

John – 25 Aug 1651

James – 30 Jun 1653

Mary – 10 Jan 1655

The town of Chelmsford was incorporated in 1655 and the Nutting family decided to migrate westward. More children were added to their family:

Josiah – 10 Jun 1658 (died 10 Dec 1658)

Sarah – 07 Jan 1659 (died in infancy)

The pastor of their church in Chelmsford, Reverend John Fiske, kept a notebook and recorded the following about the Nutting family:

“Their Admission to the Church “29 of 4*, ‘56 (1656)”

“This day testim: was giuen touching Jo: Nutting & his wife, by Isa. Lernet, Sim: Thompson, and Abram Parker.”

“13 of 5, ‘56, …. there was joyned to the Church Jo: Nutting, after his Relation made, . . . assent given to the p’fession of faith & Cov’t of the Church.”

“It. Jo: Nuttin’s wife, hr Relation being repeated by the officer of the Church.”

“Three of Jo: Nutting’s Children baptized, – John, James, Mary. 3 of 6, ‘56.”

“(Date uncertain) Josiah Nutting, Br. Nutting’s child, baptized.”

“13 or 12, 59, Sarah Nutting, dau. of Br and sister Nutting, baptized.”

Around the time John and his family removed to Chelmsford, John Winthrop petitioned the Great and General Court for a new plantation at Petapawag which bordered Chelmsford. The Nutting family, being longtime friends of the Winthrops, began to consider yet another removal to the new settlement which would be called Groton, named after Groton Manor, England.

Perhaps surprisingly, the Nuttings and two other families who were considering the move to Groton were met with opposition from the Church. Nutting family historian Reverend John Keep Nutting wrote:

To us it would seem strange for a member about to remove from one town to another, to be expected to ask leave from the church. In those days it was quite different. Each new settlement was in reality, so far as all local interests were concerned, a small nation by itself. Its voting citizens were the members of the church – none others. And upon these the town rested for defence and for up-building. Solemn vows bound these to mutual defence and helpfulness. When therefore three leading families proposed to leave Chelmsford, it was no small matter.

On September 9, 1661 the following was recorded:

“On this day the three Bre: Ja: Parker, Ja: Fiske, Jo: Nutting, ppounded to the church: That they, haueing some thoughts and inclinations to a Remoue, desired to ppound it to the church, that (as they may see God to make a way for them) they may have the church’s loueing leaue so to doe, &their prayers for them, for a blessing of God vpo: their undertaking.”

The pastor . . . put it to vote, to see if . . . they should giue their grounds. . . .”

“Heerpo: scarce a man in the church but p’sently said, ‘The grounds The grounds!’”

The discussion (and controversy) continued for awhile apparently:

“After much Agitation, . . . ca: to this Result for answr. That the case was doubtful to us at present . . . (but if the brethren) shall in the meane time setle them in their pposed way . . . we shall leaue the matter with God.”

Following a vote on December 23, 1661, there are no more mentions of the three families until they are granted letters allowing them to join the Groton church. So, perhaps the removal took place either in late 1661 or early 1662. John Nutting had proposed that his move to Groton would allow him to settle near the meetinghouse there. On September 21, 1663 a vote was recorded wherein John Nutting was appointed the janitor of the meetinghouse:

Sep: 21:63 It is agreed by ye Towne with John Nuttin & voted that he the said John shall keepe cleane the meeting house this ye(ar) or cause it to be kept cleene & for his labors he is to h(ave) forrteen shillings.

John immersed himself in the civic affairs of his new hometown. In November of 1663 he was chosen as a selectman, the highest office in the town. He was subsequently re-elected to the same office in 1667 and 1669. In 1668 he took on the additional office of constable.

More children were born to John and Sarah after their move to Groton:

Sarah – 29 Mar 1663

Ebenezer – 23 Oct 1666

Jonathan – 17 Oct 1668

Deborah (not recorded)

Their home was said to have been large and secure enough to serve as a garrison in Groton, especially during King Philip’s War (1675-1678). King Philip was the name the English gave to Metacomet, the war chief of the Wampanoag Indians, he being the second son of Massasoit.

After the colonists arrived they made an alliance with Massasoit, and for the most part peace was maintained, although increasingly the English were making deeper incursions onto Indian lands. After Massasoit died, Metacomet ascended to leadership and began to realize that his land was slowly but surely being overtaken by colonists who wished to explore and live farther west than the original settlements. At the time, Groton was one of the most westward of settlements in the colony.

With stirrings of war the settlers began to prepare by fortifying five homes (John’s being one) which would serve as garrisons. Trouble began on March 2, 1676 when Indians pillaged deserted homes and took cattle and swine. On March 9, four settlers were attacked – one was killed, two escaped and one was taken prisoner (later escaping).

On March 13, approximately four hundred Indians made their way to Groton, led by a chief named Monoco or Monojo – the settlers called him “One-eyed John”. Early that morning, guards at John Nutting’s garrison saw two Indians “skulking about”. Those stationed at the garrison probably assumed there were no other Indians close by and decided to attack, but it turned out to be an ambush. John Nutting, a corporal, was one of the leaders.

As the attack escalated, panic ensued and several fled, including some of the men. A second ambush was mounted by Monojo and his warriors. They took over the garrison and kept the battle going until nightfall. According to family historian John Keep Nutting:

As the attack escalated, panic ensued and several fled, including some of the men. A second ambush was mounted by Monojo and his warriors. They took over the garrison and kept the battle going until nightfall. According to family historian John Keep Nutting:

Night put an end to active hostilities, but Monojo called up Captain Parker, reminding him that they were old neighbors, and held quite a conversation with him. He discussed the cause of the war and spoke of making peace. He naturally ridiculed the white man’s worship of God in the Meetinghouse, seeing that God had not helped them. He boasted that he had burnt Medfield and Lancaster, would now burn Groton, then “Chelmsford, Concord, Watertown, Cambridge, Charlestown, Roxbury, and Boston”, adding, “What me WILL that me DO!” The chronicler, however, is pleased to add to his account that not many months later this boaster was seen marching through the Boston streets which he had threatened to burn “with an halter about his neck, wherewith he was hanged at the town’s end”, in September of the same year.

John Nutting had been killed in the first attack. Historians presume that, as records indicate, the Indians cut off his head and “did set it vpon a pole, looking unto his own lande.” Apparently the rest of his family had safely escaped. John Nutting died defending his home, family and friends. Sarah’s name appeared a few months later in Woburn town records, referred to as “Widow Nutting”.

An apt summary of John Nutting’s life was penned by Reverend Nutting:

It is equally certain that he was truly a pious man. Among the things he coveted, was a home “nigh to the Meetinghouse”, so that he and his wife and his “smale childr:” might not miss the beloved “ordin:”. His humble position as sexton or janitor of the Meetinghouse, both at Chelmsford and at Groton, could not have been because he needed the trifling stipend, but rather because he felt it to be an honor to be “a door keeper in the house of the Lord.”

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Feuding’ and Fightin’ Friday: Spikes-Gholson Feud

This family feud simmered quite awhile before it ended in the early 1900’s in eastern New Mexico, in an area now known as Quay County. The feud began in east Texas during the Civil War when the two patriarchs of the Spikes and Gholson families crossed paths, or should I say just “crossed.”

This family feud simmered quite awhile before it ended in the early 1900’s in eastern New Mexico, in an area now known as Quay County. The feud began in east Texas during the Civil War when the two patriarchs of the Spikes and Gholson families crossed paths, or should I say just “crossed.”

This article has been “snipped”. The article was updated, with extensive new research and sources, for the September-October 2020 issue of Digging History Magazine. It is included in the article entitled “Feuds, Fugitives and the Founding of Quay County”. This issue is Part II of a short series of articles dedicated to New Mexico history and how to find the best genealogical records. The September-October 2020 issue is available here: https://digging-history.com/store/?model_number=sepoct-20

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

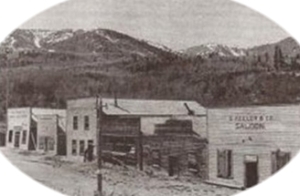

Ghost Town Wednesday: Eagle City, Idaho

This ghost town in the Coeur d’Alenes of Idaho, although once a thriving gold mining town, might not be worthy of a mention, but for the fact that Wyatt Earp and Josephine “Sadie” Marcus arrived there in early 1884 for the Coeur d’Alene gold rush. Titus Blessing, subject of a Tombstone Tuesday article awhile back, was also there and possibly crossed paths with the Earps.

This ghost town in the Coeur d’Alenes of Idaho, although once a thriving gold mining town, might not be worthy of a mention, but for the fact that Wyatt Earp and Josephine “Sadie” Marcus arrived there in early 1884 for the Coeur d’Alene gold rush. Titus Blessing, subject of a Tombstone Tuesday article awhile back, was also there and possibly crossed paths with the Earps.

After leaving behind the OK Corral shootout in Tombstone and the Dodge City “war” in Kansas, Wyatt and Sadie headed to Idaho with Wyatt’s brother Jim, landing in Eagle City. Eagle City was the first mining camp to spring up in the area when gold was discovered by Andrew Pritchard in 1882. In early 1884, miners were arriving daily, many living in tents.

Wyatt and Sadie came to make their fortune as well, although not just as miners. They purchased a round circus tent – forty-five feet high and fifty feet in diameter – and opened a dance hall. Later they opened the White Elephant Saloon. Wyatt’s attempts at being a businessman always seemed to be thwarted by being drawn into some local controversy or conflict. Such was the case in Eagle City as well.

Wyatt and Sadie came to make their fortune as well, although not just as miners. They purchased a round circus tent – forty-five feet high and fifty feet in diameter – and opened a dance hall. Later they opened the White Elephant Saloon. Wyatt’s attempts at being a businessman always seemed to be thwarted by being drawn into some local controversy or conflict. Such was the case in Eagle City as well.

After A.J. Pritchard discovered gold, he began filing multiple claims in the area, his holdings being quite extensive. When the Earps came to Eagle City they formed their own mining company and decided to challenge Pritchard’s claims. The other partners in the company were Danny Ferguson, John Hardy, Jack Enright and Alfred Holman. Pritchard and the Earps found themselves in court frequently, arguing for miners’ rights and defending claim jumps. Pritchard won at least one suit where he claimed the Earps had jumped a claim.

Wyatt claimed four mines: the Consolidated Grizzly Bear, the Dividend, the Dead Scratch and the Golden Gate. His brother claimed the Jesse Jay. As if he wasn’t busy enough running the dance hall and saloon and mining, Wyatt took the job of deputy sheriff in Kootenai County. In late March, Wyatt would again be involved in a gunfight, although this time as peacemaker.

Wyatt’s partners (Ferguson, et al) were claiming to have legally purchased a lot in downtown Eagle City from Philip Wyman. Another gentleman, William Buzzard, claimed that he had purchased the lot from Sam Black whereon he built a cabin. Enright claimed the cabin was not located on the same lot he purchased. Nevertheless, Buzzard began hauling lumber to the site to begin construction of a hotel.

On March 29, Buzzard pointed a rifle at Enright and ordered him off his property. Enright left, but when he returned he was accompanied by Ferguson, Holman and William Payne who were, as they say, “armed to the teeth.” Bullets soon began flying, with two bullets hitting Buzzard’s hat and Enright narrowly missing a bullet in his face.

The Earp brothers stepped in, and as the report goes, took on the role of peacemakers:

with characteristic coolness, they stood where the bullets from both parties flew about them, joked with the participants upon their poor marksmanship, and although they pronounced the affair a fine picture, used their best endeavors to stop the shooting.

The Shoshone County sheriff ordered Buzzard to stop shooting, while Wyatt persuaded Enright and his friends to give up their guns. Later Buzzard and Enright had a smoke together and worked out their differences apparently. However, more than a decade later Buzzard would claim that Wyatt Earp was the instigator of the “lot-jumping claims” – again his reputation would be tainted.

A few months after Enright and Buzzard battled, Enright was involved in another gunfight, this time with the manager of the Eagle City Pioneer, Henry Bernard. Enright was shot by Bernard and died. Not long afterwards, the Earps sold out (at a loss) and left Eagle City. Presumably, the town of Eagle City began to fade away sometime later in 1884 or the following year since in 1885 the town of Murray, built just up the creek from Eagle City, became the county seat of Shoshone County.

Today not much remains of Eagle City except a few obscure graves. Murray’s population once numbered in the hundreds but today is home to mostly retirees and considered a “semi-ghost town.” The Sprag Pole Inn and Museum is said to be a “must-visit” for its exhibits highlighting the gold rush era and the history of the area.

Stay tuned for next week’s Tombstone Tuesday article highlighting three notable and/or infamous residents of Murray, Idaho.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Tombstone Tuesday: John Wesley Spikes

John Wesley Spikes was born in Alabama on September 29, 1841 to parents John Edward and Nancy (Colquehoune) Spikes. In 1843 his mother passed away and his father married Lucinda Carter on January 11, 1844. Lucinda was a widow with a young son, also named John, and she and John Edward had two children together before the family migrated west to Texas in 1846. They first settled along the Sabine River and later moved to Kaufman County, Texas in 1849.

John Wesley Spikes was born in Alabama on September 29, 1841 to parents John Edward and Nancy (Colquehoune) Spikes. In 1843 his mother passed away and his father married Lucinda Carter on January 11, 1844. Lucinda was a widow with a young son, also named John, and she and John Edward had two children together before the family migrated west to Texas in 1846. They first settled along the Sabine River and later moved to Kaufman County, Texas in 1849.

According to Kaufman County history, John Edward was a farmer and slave owner with a different philosophy. He treated his slaves as family, provided for their welfare and allowed them to be buried next to his own family’s plot. He helped to establish and build a school in Kaufman, while his family and farm continued to grow and prosper.

This article has been “snipped”. The article was updated, with new research and sources, for the September-October 2020 issue of Digging History Magazine. It is included in the article entitled “Feuds, Fugitives and the Founding of Quay County”. This issue is Part II of a short series of articles dedicated to New Mexico history and how to find the best genealogical records. The September-October 2020 issue is available here: https://digging-history.com/store/?model_number=sepoct-20

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Ghost Town Wednesday: Kimberly, Utah

Kimberly, Utah, located in the northwest part of Piute County, began to be settled in the 1890’s. In 1888 prospectors came to the Tushar Mountains to find a storied lost mine called “Trapper’s Pride.” It may not have been the mine they were searching for, but the men discovered two large veins of both gold and silver and founded the Gold Mountain Mining District in April of 1889.

Kimberly, Utah, located in the northwest part of Piute County, began to be settled in the 1890’s. In 1888 prospectors came to the Tushar Mountains to find a storied lost mine called “Trapper’s Pride.” It may not have been the mine they were searching for, but the men discovered two large veins of both gold and silver and founded the Gold Mountain Mining District in April of 1889.

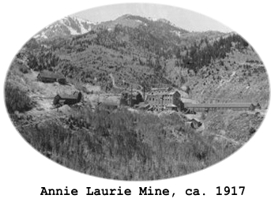

The Annie Laurie Mine, named after Newton Hill’s daughters, was opened in 1891 and became one of the most productive in the mining district. Another prospector, William Snyder, developed the Bald Mountain Line. The town site he founded was first called Snyder City, later changed to Kimberly after an investor from Pennsylvania, Peter Kimberly, bought the Annie Laurie and other area mines. He combined all his holdings into the Annie Laurie Consolidated Mining Company and constructed a cyanidation plant to process the gold.

With the mill in place and the abundance of gold, silver and other precious metals, Kimberly began to boom. The town was divided into Lower Kimberly and Upper Kimberly, the lower part being the business district and the upper residential. In the book A History of Piute County by Linda King Newell (1999), Lower Kimberly is described:

With the mill in place and the abundance of gold, silver and other precious metals, Kimberly began to boom. The town was divided into Lower Kimberly and Upper Kimberly, the lower part being the business district and the upper residential. In the book A History of Piute County by Linda King Newell (1999), Lower Kimberly is described:

Its main street twisted like a horseshoe around the contour of the canyon. Lower Kimberly had a post office, school, dance hall, doctor’s office, two or three general stores, several “specialty” shops, a slaughterhouse, three livery stables and as many saloons, two hotels, two barbershops, two boardinghouses, a dairy, and two newspapers, the Free Lance and the Nugget. The jail, one of the few brick structures in the town, stood toward the back of the small bench that provided a level area for some of the buildings. Inside were two iron cells, with only enough room on the front for the doors to open without hitting the wall. Those who supposedly knew said it was the strongest jail within a hundred miles.

A good jail was a good idea, since like many other mining booms town, it was a wild and woolly place. In 1900 the Gold Mountain School District was established and a school was built. Because of deep winter snows (the town was situated at approximately 9,000 feet), children attended school from April through November. Enrollment was at its highest in 1903 with 89 students.

A good jail was a good idea, since like many other mining booms town, it was a wild and woolly place. In 1900 the Gold Mountain School District was established and a school was built. Because of deep winter snows (the town was situated at approximately 9,000 feet), children attended school from April through November. Enrollment was at its highest in 1903 with 89 students.

The early 1900’s were the most productive for the area mines. After the cyanide mill was built in 1902, two hundred and fifty tons of ore could be processed in one day. Gold from the mines was shipped by stagecoach in bars measuring 6x10x10 inches and valued at over $20,000 each. The bars were stacked on the floor of the coach, between passengers’ feet, and of course, an armed guard always accompanied each shipment.

By 1902 the Annie Laurie alone employed three hundred miners, paid three dollars a day, and Kimberly’s population rose to five hundred. That year Peter Kimberly was said to have had an offer to sell out for five million dollars. By 1905 the mine was at its peak production level running three shifts, seven days a week.

Entertainment wasn’t lacking in Kimberly. The dance hall, built by the mining company, had one of the finest dance floors in the state. A young doctor, J.S. Steiner, established his medical practice by charging each family one dollar a year. If services were required, no additional fees were collected. There was constant traffic up and down the mountain roads carrying gold to the railroad at Sevier and supplies into Kimberly.

The town would begin its decline, however, in 1905 when Peter Kimberly died. The company was sold to a British company which lacked experience in managing mining operations. When the new owners instituted a scrip payment system, redeemable only at the company store, miners began to quit. The new company plunged into debt after building a new mill, followed by the Panic of 1907 which brought even more financial uncertainty.

In 1910 the Annie Laurie Consolidated Mining Company declared bankruptcy and with mine closure the demise of Kimberly soon followed. That year’s census enumerated only eight residents. The following year the company’s property, worth millions, sold at auction for a mere $49,000. Three men maintained the tunnels and buildings for a time for the new company, Sevier-Miller Coalition Company. In 1931, more workers were hired to remove a large block of ore. However, by 1938 the gold and silver were depleted and the mines were permanently closed. By 1942 most buildings had collapsed or were moved elsewhere.

One notable person born in Kimberly in 1905, Ivy Baker Priest, served as President Dwight Eisenhower’s Treasury Secretary from 1953 to 1961. She was the mother of Pat Priest, the actress who played Marilyn Munster on the television show The Munsters.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Tombstone Tuesday: Horatio Nelson Jackson

Horatio Nelson Jackson was born on March 25, 1872 in Toronto, Ontario, Canada to parents Reverend Samuel Nelson and Mary Ann (Parkyn) Jackson. Samuel was a minister who was also born in Canada (Brome), although according to census records Samuel’s father had been born in Massachusetts, thus it is possible that he could claim United States citizenship as well. Mary Ann was Canadian by birth and she and Samuel had seven children, the first two dying in infancy, followed by five sons who all lived to adulthood. Not long after she and Samuel married in 1866, Mary Ann completely lost her hearing and became an expert lip-reader in order to communicate.

Horatio Nelson Jackson was born on March 25, 1872 in Toronto, Ontario, Canada to parents Reverend Samuel Nelson and Mary Ann (Parkyn) Jackson. Samuel was a minister who was also born in Canada (Brome), although according to census records Samuel’s father had been born in Massachusetts, thus it is possible that he could claim United States citizenship as well. Mary Ann was Canadian by birth and she and Samuel had seven children, the first two dying in infancy, followed by five sons who all lived to adulthood. Not long after she and Samuel married in 1866, Mary Ann completely lost her hearing and became an expert lip-reader in order to communicate.

According to 1900 census records, Horatio entered the United States in 1873. Whether or not he claimed dual citizenship by virtue of his father perhaps claiming dual citizenship, is not clear. In the 1920’s Horatio applied for passports as a sworn citizen of the United States (although his birthplace is noted in all records as Toronto). Nevertheless, after completing his public school education, Horatio entered the University of Vermont to study medicine at the age of eighteen (his father has also received his degree in medicine from the same institution in 1871).

According to 1900 census records, Horatio entered the United States in 1873. Whether or not he claimed dual citizenship by virtue of his father perhaps claiming dual citizenship, is not clear. In the 1920’s Horatio applied for passports as a sworn citizen of the United States (although his birthplace is noted in all records as Toronto). Nevertheless, after completing his public school education, Horatio entered the University of Vermont to study medicine at the age of eighteen (his father has also received his degree in medicine from the same institution in 1871).

This article was enhanced, with sources, and published in the June 2018 issue of Digging History Magazine. Preview the issue here or purchase here. I invitey you to check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

This article was enhanced, with sources, and published in the June 2018 issue of Digging History Magazine. Preview the issue here or purchase here. I invitey you to check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!