This “battle” only lasted about ten minutes, and perhaps only receiving historical mention because from it emerged the legend of James “Jim” Bowie, expert knife-fighter, who less than a decade later famously perished at the Battle of the Alamo.

This “battle” only lasted about ten minutes, and perhaps only receiving historical mention because from it emerged the legend of James “Jim” Bowie, expert knife-fighter, who less than a decade later famously perished at the Battle of the Alamo.

James Bowie was born in Kentucky in 1796, the son of Rezin and Elve Ap-Catesby (Jones) Bowie. By 1801 his family had migrated to Rapides, Louisiana and sworn allegiance to the Spanish government. During his teen years, James hauled lumber down the river to market. Fond of fishing and hunting, it is said that he also rode wild horses and alligators (maybe more legend than fact). James and his brother Rezin decided to join Andrew Jackson’s forces during the War of 1812, but soon after their decision to join the war had officially ended.

After the war James and his brother were involved in the slave trade. Bowie would purchase slaves from the pirate Jean Lafitte and then sell them in St. Landry Parish. When they had accumulated a fortune of $65,000, they exited the slave trade business and turned to land speculation, making friends with local wealthy plantation owners.

After the war James and his brother were involved in the slave trade. Bowie would purchase slaves from the pirate Jean Lafitte and then sell them in St. Landry Parish. When they had accumulated a fortune of $65,000, they exited the slave trade business and turned to land speculation, making friends with local wealthy plantation owners.

When James applied for a loan from the local bank, he was turned down. Major Norris Wright was a bank director and neighbor of the Bowies, and said to have been responsible for blocking the loan. Their relationship was contentious at times – the Bowies had once opposed him in a sheriff’s election, supporting Wright’s opponent. When the two men met unexpectedly in Alexandria, Wright shot Bowie point-blank — although the bullet was deflected, some say by a silver dollar in his pocket. Bowie’s gun misfired (or perhaps he was unarmed) so he wasn’t able to defend himself. Legend has it that Rezin then gave James a large butcher-type knife to carry for his protection so he would never be without a means to defend himself. Later the knife would be called a “Bowie Knife,” especially after the incident that happened the following year.

Two men, Samuel Levi Wells III and Dr. Thomas Maddox, had challenged each other to a duel. The face-off was to be held on a sandbar just north of Natchez, Mississippi on September 19, 1827. Samuel Wells later gave his own account:

I was invited by Dr. Maddox, not long since, to an interview without the limits of the state, I met him at Natchez, on the 18th inst. and on the 18th I was challenged by him. I appointed the 19th for the day, and the first sand beach above Natchez, on the Mississippi side, for the place of meeting. We met, exchanged two shots without effect, and made friends.

Wells and his friend Major George McWhorter and Wells’ surgeon, Dr. Cuney (everyone needs to have their surgeon present at a duel!) were invited by Dr. Maddox and his friend Colonel Crain and surgeon Dr. Cuney to the woods where other friends, excluded from the dueling field, had stationed themselves. As they were walking over to the area where they would partake of “after-dueling refreshments,” they were met by General Cuney, James Bowie and Thomas Jefferson Wells, Samuel’s brother.

General Cuney inquired as to how the affair had been settled and Wells told him that he and Dr. Maddox had “exchanged two shots and made friends.” Wells continued his version of the events:

He [General Cuney] turned to Colonel Crane [sic] who was near me, and observed to him that there was a difference between them, and that they had better return to the ground & settle it as Dr. Maddox and myself had done. Dr. Cuney and myself interposed and stated to the General that that was not the time nor the place for the adjustment of their difference; the General immediately acquiesced; and his brother had turned to leave him, when Crane [sic], without replying to General Cuney, or saying one word fired a pistol at him, which he carried in his hand, but without effect. I then stepped back one or two paces, when Crane [sic] drew from his belt another pistol, fired at and wounded Gen. Cuney in the thigh; he expired in about fifteen minutes.

Apparently Colonel Crain had pre-meditatively planned the confrontation with Cuney. Crain had been overheard earlier telling friends in Natchez that if the General made an appearance at the duel he intended to kill him, and as Wells puts it, “and well has he kept his promise.” A man referred to only as “Dr. Hunt” had tried to warn Cuney the night before but was unable to locate him.

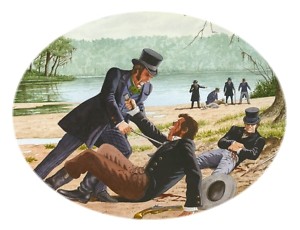

After Crain killed Cuney, he drew his gun, fired and wounded Bowie in the hip. Bowie drew his knife and rushed Crain. However, Crain struck Bowie’s head with his empty pistol, bringing Bowie to his knees, breaking the pistol. Virgil E. Baugh, author of Rendevous at the Alamo: Highlights in the Lives of Bowie, Crockett, and Travis, provides the rest of the story, taken from the recollections of a Bowie family historian and a Southern newspaper article:

Before [Crain] could recover he was seized by Dr. Maddox who held him down for some moments, but, collecting his strength, he hurled Maddox off just as Major Wright approached and fired at the wounded Bowie, who, steadying himself against a log, half buried in the sand, fired at Wright, the ball passing through the latter’s body. Wright then drew a sword-cane, and rushing upon Bowie, exclaimed, “Damn you, you have killed me.” Bowie met the attack, and seizing his assailant, plunged his “bowie-knife” into his body, killing him instantly. At the same moment Edward Blanchard shot Bowie in the body, but had his arm shattered by a ball from [Thomas] Jefferson Wells.

The aftermath of the “fight at the duel”: Major Wright and General Cuney killed; Bowie, Crain and Blanchard badly wounded. According to the family historian, Colonel Crain brought water for Bowie. Bowie “politely thanked him, but remarked that he did not think Crain had acted properly in firing upon him when he was exchanging shots with Maddox. In later years Bowie and Crain became reconciled, and, each having great respect for the other, remained friends until death.”

Bowie was taken away and presumed to have been mortally wounded – but Bowie recovered. What would also become legendary was Bowie’s ability to survive. The earliest news articles (even though published weeks after the actual incident) were reporting that Bowie was not expected to survive. But survive he did to fight another day.

Bowie was taken away and presumed to have been mortally wounded – but Bowie recovered. What would also become legendary was Bowie’s ability to survive. The earliest news articles (even though published weeks after the actual incident) were reporting that Bowie was not expected to survive. But survive he did to fight another day.

Witnesses began to spread the word of Bowie’s knife skills – they all remembered Bowie’s “big butcher knife.” Thus began the legend of Jim Bowie and his formidable knife-fighting skills. Thereafter, newspaper articles written about fights and disputes would often make mention of a “Bowie Knife.” A blacksmith by the name of James Black made the first official Bowie Knife for Bowie in 1830. After Jim Bowie’s death at the Alamo in 1836, Black did a brisk business selling the knives to pioneers headed to Texas.

The “Battle of the Sandbar” wasn’t the last duel/fight that Jim Bowie would be involved in. In 1829 he tangled with John “Bloody” Sturdivant in Natchez. He had traveled to Natchez to help the son of a family friend, Dr. William Lattimore. The son had been duped by Sturdivant in a crooked faro game and Bowie was there to help even the score. Bowie, although not an expert card player, was able to win back the son’s losses.

Sturdivant was bragging that had he been at the Sandbar duel he would have made sure Bowie had died that day. When Bowie returned to respond to Sturdivant’s threats, he was challenged to a knife fight with these rules: the two men would have their left hands tied together across a table. Bowie accepted the terms and swiftly knifed his opponent’s right arm. Although not mortally wounded, Bowie had made his point with Sturdivant. According to Rendevous at the Alamo, Sturdivant hired three assassins to hunt down and kill Bowie. Although no official accounts remain, it is said that Bowie killed all three men “in his first fight using Black’s knife.”

Bowie knives are still made today and sold ubiquitously, even at Walmart, where they are advertised as: “This Winchester Large Bowie Knife is a gargantuan, multi-purpose tool that will come in handy in nearly any situation. Its beefy 8.75″ fixed blade is made from stainless steel, so it is durable and dependable.”

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Trackbacks/Pingbacks