Ghost Town Wednesday: Swastika, New Mexico

Today, this would be considered an unfortunate name for a town, ghostly or otherwise. Believe it or not, years ago the swastika symbol was widely used. It was also used by Native American tribes like the Navajos, Hopis, Apaches and others (although later abandoned). The 45th Infantry Division of the United States military used the symbol until the 1930’s. Apparently, it was in wide use in the state of New Mexico, and not just by the Native Americans.

Today, this would be considered an unfortunate name for a town, ghostly or otherwise. Believe it or not, years ago the swastika symbol was widely used. It was also used by Native American tribes like the Navajos, Hopis, Apaches and others (although later abandoned). The 45th Infantry Division of the United States military used the symbol until the 1930’s. Apparently, it was in wide use in the state of New Mexico, and not just by the Native Americans.

This article is no longer available for free at this site. It was re-written and enhanced with sources as part of an article entitled “Bullets, Barons, Boom and Bust: The Ghost Towns and Storied History of Colfax County”, published in the July-August 2020 issue of Digging History Magazine. Should you prefer to purchase the article only, contact me for more information.

This article is no longer available for free at this site. It was re-written and enhanced with sources as part of an article entitled “Bullets, Barons, Boom and Bust: The Ghost Towns and Storied History of Colfax County”, published in the July-August 2020 issue of Digging History Magazine. Should you prefer to purchase the article only, contact me for more information.

I invite you to check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? ???? No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Surname Saturday: Munger

There at least two schools of thought regarding the origins of today’s surname. Ultimately, it appears to me that its origins were most likely Germanic, although the first settlers who came to America in the 1630’s came directly from England. Two sources indicate the name had English origins with different meanings, and they state:

- An English variant of Monger (Dictionary of American Family Names).

- *The name was brought to England during the Norman Conquest of 1066 and was a locational name “of de la Monceau”, meaning hill or mound. In the thirteenth century records show two people, one named Robert de Muncella in County Wiltshire and another named Robert de Munceaux in County Norfolk (4Crests.com)

For the English theory, spelling variations of the name might include “Monger”, “Mungor” or “Mounger” (and probably others).

The other source, House of Names, traces the name back to its Germanic origins. Their theory is that the name derives from the German word “ungarn” which means “someone from Hungary (a Magyar).” The name, was first seen in Bohemia, “where the name was closely identified in early medieval times with the feudal society that played a prominent role throughout European history. Bearers of Munger would later emerge as a noble family with great influence, having many distinguished branches, and become noted for involvement in social, economic and political affairs.”

The other source, House of Names, traces the name back to its Germanic origins. Their theory is that the name derives from the German word “ungarn” which means “someone from Hungary (a Magyar).” The name, was first seen in Bohemia, “where the name was closely identified in early medieval times with the feudal society that played a prominent role throughout European history. Bearers of Munger would later emerge as a noble family with great influence, having many distinguished branches, and become noted for involvement in social, economic and political affairs.”

Spelling variations of the German surname include Unger, Ungerer, Ungarer, Ungare, Ungars, Ungers, Ungert and many more, according to House of Names.

If true regarding Germanic roots, why did the first Munger immigrating to America come from England and not Germany? In 1915, the Munger family history was published by J.B. Munger of Springfield, Massachusetts, spanning the years from 1639, when J.B.’s ancestor Nicholas Munger arrived, until 1914.

J.B. believed that Nicholas was “the individual personally responsible for our being here.” He further explained:

As to the individual, I have answered: NICHOLAS MUNGER. As to the nationality, English; evolved through the “melting pot” from several of the Teutonic tribes who came across from the far east of Europe, gradually moving westward. The historian has said that “The tribes which later constituted the German nation, lived along the shores of the Caspian Sea. The vanguard of the tribes which swept across the middle of Europe from Asia to the West, were the Celts. After them came the Teutonic tribes, and the hard crowded Celts were forced out upon the westernmost edge of Europe, across the channel to the British Isles, where they are represented to this day by the Welsh, the Irish, and the Highland Scots.”

Immigration records, at least those of the nineteenth century, seem to lean more heavily in favor of Germanic origins (Germany, Switzerland and Bohemia), this according to New York passenger lists. Nevertheless, J.B. Munger believed that the majority of those bearing the Munger surname at the time his research was published were directly descended from Nicholas Munger, an Englishman. Oh, and he had his own theory as to the name’s meaning as well:

Monger: Anglo-Saxon Mancgere. Originally a merchant of the highest class. Aelfric’s Mancgere is represented as trading in purple and silk; gold, wine, oil &c. The Mancgere (merchant) of Saxon times was a much more important personage than those who, in our day, bear the name. He was the prototype of the merchant princes of the nineteenth century; he was a dealer in many things which the ships-men brought from many lands.” (From English Surnames)

Admittedly, J.B. Munger was aware that the name was seen among English, German and the Dutch (with various spellings). A Swedish variation of the name would be “Mungerson.” He related a story that a United States government official, once visiting Geneva, Switzerland, was told his name (Munger) was German and was to be written as “Münger” which would have rendered the pronunciation of the “u” as “e” or “ew”.

He stated he had never attempted “researches on the ‘other side,’ but have confined our labors to this country [England]. We know the first arrival came from England; that he spelled his name MUNGER, as did his children and grandchildren, and following generations, and as it is yet spelled by his descendants in the territory where he first established himself in AMERICA as a ‘Freeman.’”

Nicholas Munger

J.B. Munger claimed to have very little definitive information regarding Nicholas. Although his name did not appear in ship passenger records, many believed that Nicholas came to America with the Henry Whitfield colony and was apprenticed to William Chittenden, a member of the company which settled the town of Guilford, Connecticut.

In 1652 Nicholas took the Oath of Fidelity and became a Freeman. In that day one had to have attained the age of at least twenty-one before being granted such status, so perhaps Nicholas was born around 1630 or 1631. He was referred to in Henry Goldham’s will as a son-in-law, which could have also meant step-son, according to J.B. Munger. Given the fact that Nicholas later married, the step-son theory seems the most plausible.

Nicholas married Sarah Hall on June 2, 1659 at Guilford and died on October 16, 1668 after he and Sarah had two sons, John and Samuel, in the early 1660’s.

Asahel Munger

Asahel Munger was born in Fairhaven, Connecticut in 1805 to parents Daniel and Eunice Munger. J.B. Munger had very little to say about Asahel in his book, but history records that Asahel met a tragic end around 1840 while serving as a missionary.

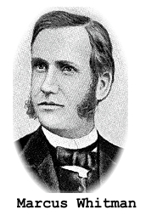

In the preface to his published diary, it indicates that Asahel and his wife Eliza were sent out from the North Litchfield Congregational Association of Connecticut and left for the journey west from Oberlin, Ohio. They were sent out as missionaries in 1839 with fellow missionary J.S. Griffin to the Oregon Territory. They were said to have traveled with fur trappers and wintered with Marcus Whitman, a missionary to the Cayuse Indians.

Asahel began a journal on May 4, 1839, essentially a long letter to his mother which detailed their arduous journey. Eliza was sick quite a bit and along the way they encountered bands of Indians in late May. However, on June 1 Asahel recorded that they hadn’t been “molested at all by the Indians.”

It appears that their journey continued seven days a week, perhaps even on the Sabbath. Asahel would often record the Sabbath as “a dreary day”. On June 9, “this is a gloomy Sabbath only for the presence of Jesus.” A week later he wrote again of a dreary Sabbath:

Oh how we need a Sabbath, our hunters went out to kill game, slaughtered 2 Buffalo and one Elk either of which had more meat than was consumed. The trust of my soul is in God. I will lean on Him. It is good to get near Him in time of trouble.

On June 30, they traveled on, Asahel communing with God as he traveled along. By July 7 they had reached the encampment of the American Fur Company and had the opportunity to have church services, preaching to both white men and Indians.

After learning that Marcus Whitman was in need of a carpenter, Asahel struck a deal and the Mungers would spend the winter with the Whitmans. Their relationship was cemented early on – Whitman’s wife Narcissa declaring, “It seems as if the Lord’s hand was in it in sending Mr. and Mrs. Munger here just at this time, and I know not how to feel grateful enough.”

After learning that Marcus Whitman was in need of a carpenter, Asahel struck a deal and the Mungers would spend the winter with the Whitmans. Their relationship was cemented early on – Whitman’s wife Narcissa declaring, “It seems as if the Lord’s hand was in it in sending Mr. and Mrs. Munger here just at this time, and I know not how to feel grateful enough.”

The missionary board that was sponsoring the Whitmans warned, however, against fraternizing with so-called “independent” missionaries. Still, Marcus found the Mungers to be quite useful in service to his own mission. He wrote his board that: “He is a good house carpenter. In that time I hope he will finish our house & make some comfortable furniture & some farming implements.”

The Whitmans, notwithstanding their Board’s warnings, seemed to be pleased with their association with the Mungers. However, a few months later something went wrong – Asahel seemed to have gone quite mad. Narcissa wrote a friend: “Our Brother Munger is perfectly insane and we are tried to know how to get along with him.”

Marcus concluded that the Mungers must be sent home. “He has become an unsafe man to remain about the Mission as he holds himself as the representative of the church & often having revelations.” However, by this time the fur caravans were no longer operating and no one could be found to escort the Mungers back East. By this time, Asahel and Eliza also had a young child.

Instead of heading back East, the Mungers traveled further west to the Willamette Valley with two other missionary families. The move apparently did nothing to improve Asahel’s mental state. Just before Christmas of 1840, Asahel died after “attempting to demonstrate a miracle by driving nails into his hands, then burning them in the fire”, according to the National Park Service web site.

What caused Asahel to lose his sanity is unknown, and certainly a tragic tale given how his life ended. Eliza married Henry Buxton not long afterwards it appears, perhaps in 1841. The Whitmans later met their own tragic end in 1847 (look for that story one day on this blog).

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Ghost Town Wednesday: “Old Ulysses” Kansas

I was looking for an interesting ghost town to feature this week, preferably short and sweet since I’m under the weather this week with some nasty upper respiratory thing-y. I opened up one of my trusty ghost town books, Ghost Towns of Kansas by Daniel Fitzgerald. It fell open to “Old” Ulysses – what’s that about “Old”?

I was looking for an interesting ghost town to feature this week, preferably short and sweet since I’m under the weather this week with some nasty upper respiratory thing-y. I opened up one of my trusty ghost town books, Ghost Towns of Kansas by Daniel Fitzgerald. It fell open to “Old” Ulysses – what’s that about “Old”?

I soon found that there was an “Old” and a “New” Ulysses in western Kansas in Grant County. Get ready for it – it was named for who else but Ulysses S. Grant! Okay – I thought this might make an interesting article. Little did I know . . . read on.

In 1885 a town company had been formed and the town platted. On July 16, A.J. Hoisington, president of the company, signed on the dotted line. I was surprised to discover, however, that one of my Earp cousins, George Washington Earp, surveyed the town site. George was Wyatt’s first cousin and Wyatt is my third cousin, three times removed (see article here), so I suppose that would make George and I the same relation.

In 1885 a town company had been formed and the town platted. On July 16, A.J. Hoisington, president of the company, signed on the dotted line. I was surprised to discover, however, that one of my Earp cousins, George Washington Earp, surveyed the town site. George was Wyatt’s first cousin and Wyatt is my third cousin, three times removed (see article here), so I suppose that would make George and I the same relation.

George Washington Earp was born on December 13, 1864 in Montgomery County, Missouri to parents Jonathan Douglas and Dorcas (Cox) Earp. He would have heard the stories about Wyatt, and at the age of eighteen he had a “burning ambition to be a cowboy”, according to Legends of America. He headed to Dodge City about the time Wyatt and his brothers were moving on to Tombstone, Arizona (and we all know what happened there). Wyatt refused to help his cousin, believing the town too rough-and-tumble, so he instead sent George to Garden City.

Did you enjoy this article snippet? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. This article has been updated significantly  with new research and published in the July-August 2019 issue of the magazine. The magazine is on sale in the Digging History Magazine store and features these stories (100+ pages of stories, no ads):

with new research and published in the July-August 2019 issue of the magazine. The magazine is on sale in the Digging History Magazine store and features these stories (100+ pages of stories, no ads):

- “Drought-Locusts-Earthquakes-B-Blizzards (Oh My!)” – Perhaps no state is possessive of a more appropriate motto than Kansas: Ad Astra per Aspera (“To the stars through difficulties”, or more loosely translated “a rough road leads to the stars”1). By the time the state adopted its motto in 1876, fifteen years post-statehood, it had experienced not only a brutal, bloody beginning (“Bloody Kansas”) but had endured (and continued to struggle with) extreme pestilence, preceded by severe drought and even an earthquake in April 1867. In the early days being Kansan was not for the faint of heart.

- “Home Sweet Soddie” – For years The Great Plains had been a vast expanse to be endured on the way to California and Oregon. Now the United States government was making 270 million acres available for settlement – practically free if, after five years, all criteria had been met. The criteria, referred to as “proving up” meant improvements must be made (and proof provided) by cultivating the land and building a home. For many their first home would be a dugout, a sod-covered hole in the ground.

- “Wholesale Murder at Newton” – It’s called “The Gunfight at Hyde Park” or the “Newton Massacre”. One newspaper headlined it as “Wholesale Murder at Newton”, another called it an “affray” and another a “riot”. Whatever, it was bloody, and one of the biggest gunfights in the history of the Wild West, more deadly than the legendary gunfight at the OK Corral.

- “Kansas Ghost Towns” – It might be more appropriate to call this Kansas ghost town, established by Ernest Valeton de Boissière in 1869, a “ghost commune” (Silkville). Nicodemus. There was something genuinely African in the very name. White folks would have called their place by one of the romantic names which stud the map of the United States, Smithville, Centreville, Jonesborough; but these colored people wanted something high-sounding and biblical, and so hit on Nicodemus.

- “The Land of Odds: Kwirky Kansas” – For some of us the mention of Kansas invokes memories of one of the classic films of our childhood, The Wizard of Oz. With a tongue-in-cheek reference this article highlights some of the state’s history and people in a series of vignettes – some serious, some not so serious (the real “oddballs”) in a light-hearted fashion. A rollicking fun article covering a range of Kansas “oddities” and “oddballs”, including one of the most dangerous quacks to have ever practiced medicine, Dr. John R. Brinkley.

- “Mining Kansas Genealogical Gold” – One of my favorite “adventures in research” is to discover obscure genealogical records or perhaps stumble across a set of records at Ancesty.com or Fold3 which turns out to be a gold mine of information. This article highlights some real gems available at Ancestry.

- “Chautauqua: The Poor Man’s Educational Opportunity” – During an era spanning the mid-1870s through the early twentieth century, Kansans, like many Americans across the country, anticipated the summer season known as Chautauqua, an event Theodore Roosevelt called “the most American thing in America”. By 1906 when Roosevelt made such an astute observation the movement had evolved into a non-sectarian gathering, where “all human faiths in God are respected. The brotherhood of man recreating and seeking the truth in the broad sunlight of love, social co-operation.”

- And more, including book reviews and tips for finding elusive genealogical records.

Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Tombstone Tuesday: What Happened to Stephen Paul?

Stephen Paul was born in Robeson, North Carolina around 1836 to parents John H. and Mary (Wise) Paul. John and Mary had both been born in North Carolina and after they married in 1825 they produced a large family. By 1850 there were thirteen children enumerated, ranging from William (25) down to Catherine (3) – in the middle of the pack was Stephen, age 14.

Stephen Paul was born in Robeson, North Carolina around 1836 to parents John H. and Mary (Wise) Paul. John and Mary had both been born in North Carolina and after they married in 1825 they produced a large family. By 1850 there were thirteen children enumerated, ranging from William (25) down to Catherine (3) – in the middle of the pack was Stephen, age 14.

It’s likely that the Paul family had departed North Carolina sometime between 1848 and 1850, settling in Henry County, Tennessee where they were enumerated in 1850. Around the age of twenty, young Stephen Paul was married to fourteen year-old Narcissa Ann Gresham (spelled Grissum on their marriage record) in Carter County, Missouri, where the Paul family had migrated to following the 1850 census.

It’s likely that the Paul family had departed North Carolina sometime between 1848 and 1850, settling in Henry County, Tennessee where they were enumerated in 1850. Around the age of twenty, young Stephen Paul was married to fourteen year-old Narcissa Ann Gresham (spelled Grissum on their marriage record) in Carter County, Missouri, where the Paul family had migrated to following the 1850 census.

This article was enhanced, complete with sources, and published in the April 2018 issue of Digging History Magazine. The entire issue was devoted to the Civil War. Should you prefer to purchase the article only, contact me for more information.

I invite you to check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

I invite you to check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Mining History: The Rock Springs Massacre

By the mid-nineteenth century there were few Chinese immigrants who had made their way to America. In early 1849, there were only fifty-four in the entire state of California, but that would change as word spread and gold rush fever took hold.

By the mid-nineteenth century there were few Chinese immigrants who had made their way to America. In early 1849, there were only fifty-four in the entire state of California, but that would change as word spread and gold rush fever took hold.

The prospect of work, either in the mines or whatever supporting job could be found, brought Chinese men fleeing rebellion and poverty in their own country to California and beyond. Chinese immigration continued apace until in 1876 there were over 150,000 Chinese immigrants in the United States, 116,000 in California alone.

Most men came alone, calling themselves “Sojourners,” implying they never intended to stay, but rather someday would return to their homes and families in China. As menial and low-paying as some of the jobs they took, the Chinese still earned more money in America – and if they were careful and saved it, would amass what to them would be quite a fortune.

When it became necessary to build a railroad heading east out of Sacramento, it was the Chinese workers who took on the back-breaking and dangerous work of laying track and blasting tunnels through the mountains. Of the approximately twelve thousand Chinese who helped build the Central Pacific railroad line, about one-tenth, or twelve hundred, were killed.

When it became necessary to build a railroad heading east out of Sacramento, it was the Chinese workers who took on the back-breaking and dangerous work of laying track and blasting tunnels through the mountains. Of the approximately twelve thousand Chinese who helped build the Central Pacific railroad line, about one-tenth, or twelve hundred, were killed.

When the Central Pacific met the Union Pacific in Utah in 1869 there was a great ceremony – and then thousands of jobs disappeared, many of which had been filled by the Chinese. Yet, they stayed even without their families and continued to find ways to continue working, especially in the West during the mining boom years, from Tombstone, Arizona to the mining camps of Montana.

Today, the saying goes that illegal immigrants should be welcomed because “they do the work most Americans won’t”. To a certain extent that was true in the mid-to-late 1800’s for Chinese immigrants. They were willing to work and, truth be told, were probably exploited.

It became apparent that in many cases, however, Chinese workers accepting lower pay were displacing (or replacing) Caucasian workers. In the summer of 1870 white workers in San Francisco held large demonstrations – the Chinese were no longer welcome. The following year a riot broke out in Los Angeles and twenty-three Chinese were killed, yet no one was charged with their murders.

In 1882, the United States Congress unsuccessfully tried to limit the number of Chinese immigrants by passing stricter immigration laws. Years before the Chinese had worked in the gold mines, but now they were being hired to work in the coal mines, often replacing other immigrant miners of Scandinavian, Italian, Welsh or Irish heritage. Again, the Chinese were simply willing to work for much lower wages.

The Union Pacific line stretched across southern Wyoming in large part because of the area’s large deposits of coal, and the Union Pacific owned some of those mines. When the railroad became bogged down in financial difficulties, they cut miners’ pay. To continue boosting their bottom line, the company required its employees to shop in their company stores where prices were much higher. Unsurprisingly, this brought labor unrest and strikes.

After one such strike in 1875, Union Pacific brought in Chinese miners. The Chinese miners outnumbered white miners three to one at that point, and by 1885 there were six hundred Chinese and three hundred white miners working the mines of Rock Springs, Wyoming. Newspapers across the country were already filled with articles and editorials calling for stricter Chinese immigration.

After one such strike in 1875, Union Pacific brought in Chinese miners. The Chinese miners outnumbered white miners three to one at that point, and by 1885 there were six hundred Chinese and three hundred white miners working the mines of Rock Springs, Wyoming. Newspapers across the country were already filled with articles and editorials calling for stricter Chinese immigration.

On the second day of September 1885, after white immigrant miners had struck and failed in their attempts to establish a union, tensions boiled over. The Chinese, brought in ostensibly to break the strikes, were allowed to work the richest coal seams, according to History.com.

An armed mob of white miners converged on the area of Rock Springs known as “Chinatown” and began killing the Chinese, even as they scrambled to flee the mob. That day was a Chinese holiday and most of the miners were not at work. Paul W. Papa, author of It Happened in Wyoming, described the scene:

They fell upon the Chinese, beating men with the butts of their guns and robbing them. If a Chinese man didn’t have a weapon, he was released – after, of course, he was robbed of all his possessions. If a Chinese man didn’t stop, he was shot. The Chinese panicked. They ran to their homes, but found no safe haven. The mob easily broke down the doors of the hastily built shacks and beat the men as the screaming women wrapped their arms around crying children – partially to protect them and partially to prevent them from seeing their fathers being so severely beaten.

Not only were the Chinese killed, some were mutilated, scalped, decapitated or hung – some acts so despicable and heinous I won’t mention them here. At least twenty-eight Chinese were killed and about fifteen wounded, although some sources believe the toll could have been higher.

When the Chinese returned the following week, escorted by United States troops, they discovered horrifying scenes of the carnage left behind. In an essay entitled The Rock Springs Massacre, author Tom Rea describes the scene encountered by a trainload of Chinese miners:

When the Chinese returned the following week, escorted by United States troops, they discovered horrifying scenes of the carnage left behind. In an essay entitled The Rock Springs Massacre, author Tom Rea describes the scene encountered by a trainload of Chinese miners:

Perhaps the odor of burnt things gave the men some idea of what they were about to see. Mixed with it was a sicker, sweeter smell – the smell of dead things that had started to decay. The 600 Chinese coal miners had been traveling all day – toward San Francisco, Calif., they had been told, and safety. Then they stopped, and the sound of the boxcar doors being slid open came rumbling down the train. . . . the men knew immediately where they were. They were right back in Rock Springs, Wyoming. . . . Rock Springs’ Chinatown was gone. Even more horrifying, there still were bodies in what had been Chinatown’s streets. . . . Some had been buried by the coal company, but some [these] had not. Many were in pieces. These were bodies of their friends, sons, fathers, brothers and cousins, murdered by a mob of white coal miners.

The railroad, however, presumably brought the miners back to bury their dead and then get back to work. Understandably, some of the Chinese were afraid to return to work, but after the threat of being fired (and never hired again) if they didn’t return, many acquiesced and went back to the mines. Some found a way to leave Rock Springs and never returned.

Even after all of the carnage and willful murder of the Chinese, in broad daylight no less, no one would step forward as a witness. No charges were ever filed against the white miners. After Chinese diplomats tallied damages in the amount of almost $150,000, Congress finally agreed to reimburse the miners for their losses.

Camp Pilot Butte was built between Rock Springs and Chinatown and troops were stationed there for several more years. The Chinese, however, gradually departed Wyoming, even as the federal government continued to look for ways to limit their immigration to America.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Surname Saturday: Purchase

The Purchase surname originated as an occupational name, although it’s uncertain when the name began to be used as a surname and passed down to succeeding generations. According to New Dictionary of American Family Names, the name referred to “one who acted as a messenger or courier; a nickname for one who obtained the booty or gain; one who pursued another.”

House of Names indicates this surname is “a classic example of an English polygenetic surname, which is a surname that was developed in a number of different locations and adopted by various families independently. That is what I came across when researching this week’s Tombstone Tuesday article (read it here) on Philander Purchase.

House of Names indicates this surname is “a classic example of an English polygenetic surname, which is a surname that was developed in a number of different locations and adopted by various families independently. That is what I came across when researching this week’s Tombstone Tuesday article (read it here) on Philander Purchase.

The spelling variations encountered in my research for that article proved to be a bit overwhelming to trace (at least in the limited amount of time normally assigned to research for an article). Some of the known spelling variations of this surname include: Purchas, Purchass, Purches, Purchis, Purkiss, Purkess, Purkis, Purkeys, Purkys, Purkes … and I’m sure more. Possibly all related, but confusing for family researchers.

Aquila Purchase

One of the first people bearing this surname to make, or should I say attempt to make, the trek across the Atlantic to New England was Aquila Purchase. Aquila was born in 1589 to parents Oliver and Thomazine Purchase in Sommerset, England. In 1625 he was appointed as master of the Trinity School in Dorchester, a position he held until he departed for New England in 1632.

Aquila, his wife Ann and their children (it appears Ann was with child) left Weymouth, England, headed for Dorchester, Massachusetts. However, Aquila never made it to the shores of America. He died at sea but his family survived; his son John appears to have been born in 1633 after Ann arrived with her children.

Despite the fact that Aquila never lived in America, he still had an impact on its history. Interestingly, from his line came the thirteen President of the United States, Millard Fillmore:

Henry Squire (c1563-bef1649); Somersetshire, England, had a daughter:

Ann Squire (1591-1662), who married Aquila Purchase (c1588-c1633), in 1614, and had a daughter:

Abigail Purchase (1624-1675), who married Sampson Shore (c1615-c1679), in c1639, and had a son:

Jonathan Shore (1649-1724), who married Priscilla Hathorn (b. 1649), in 1669, and had daughter:

Phoebe Shore (1674-1717). who married Nehemiah Millard (1668-1751), in 1697, and had a son:

Robert Millard (1702-c1784), who married Hannah Eddy (c1704-1739), in 1726, and had a son:

Abiathar Millard (1744-c1811), who married Tabatha Hopkins (b. 1745), in 1761, and had a daughter:

Phoebe Millard (1780-1831), who married Nathaniel Fillmore, Jr. (1771-1863), in 1796, and had a son:

Millard Fillmore (1800-1874), 13th President of the United States.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Ghost Town Wednesday: Graham, New Mexico

Gold and silver were discovered in the late 1880’s in what is now southwest Catron County, New Mexico. Preferably, in order to contain costs, gold and silver needed to be processed as close as possible to the mines. However, the problem in this particular area was that Whitewater Canyon, where the majority of the mines like the Confidence, Blackbird, Bluebird and Redbird were located, was too narrow.

Gold and silver were discovered in the late 1880’s in what is now southwest Catron County, New Mexico. Preferably, in order to contain costs, gold and silver needed to be processed as close as possible to the mines. However, the problem in this particular area was that Whitewater Canyon, where the majority of the mines like the Confidence, Blackbird, Bluebird and Redbird were located, was too narrow.

The next best location was at the mouth of the canyon and in 1893 John T. Graham arrived to build the mill, and in so doing had the mill town that would spring up named after himself. The mill location, however, had its own set of challenges since there wasn’t enough water to run the steam generators. Nor was there sufficient water to supply the town of around two hundred residents.

This problem necessitated the construction of a four-inch water pipe which ran from the high mountain waters down to Graham, a distance of about three miles. To prevent freezing, the pipe was packed around with sawdust and encased in wood. By 1897, mining operations had increased substantially enough to require a larger generator, which in turn required a larger water supply.

This problem necessitated the construction of a four-inch water pipe which ran from the high mountain waters down to Graham, a distance of about three miles. To prevent freezing, the pipe was packed around with sawdust and encased in wood. By 1897, mining operations had increased substantially enough to require a larger generator, which in turn required a larger water supply.

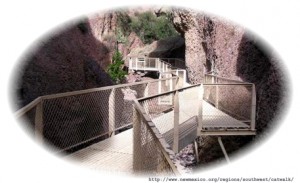

An eighteen-inch pipe was constructed parallel to the original four-inch line, and, at least for that period of history, considered to be quite an engineering feat. In order to provide adequate support for the pipes, holes had to be drilled into the canyon walls to ensure the pipes were braced sufficiently to remain in place. At various places, the pipeline rose some twenty feet above the canyon floor.

The pipeline, of course, required monitoring and repair, which meant walking along the eighteen-inch pipeline – referred to as the “catwalk”. After all the extraordinary efforts and engineering feats undertaken to provide sufficient water for the mining operations, the mill never proved to much of a success. The post office, established in 1895, closed in 1904. After the mill closed for good in 1913, the town faded away.

Still, the short-lived town of Graham and the surrounding area had its share of famous (or infamous) folks. Whitewater Canyon was a favorite hideout for Butch Cassidy and his Wild Bunch, as well as Apache warriors like Geronimo. William Henry McCarty, Jr., a.k.a. “Billy the Kid,” may have passed through the area at some point – William Antrim, his step-father, was the town’s blacksmith.

Today all that remains of the town of Graham are a few remnants of the mill. The Catwalk, however, has become a national scenic trail. Long after the town closed down and the pipelines had fallen in disrepair, the Civilian Conservation Corps, a public works project enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in response to The Great Depression, rebuilt the catwalk. Amazingly, some of the original eighteen-inch pipes provide support for the present structure. The Catwalk today is approximately a 1.1 mile hike from trail head to the end (2.2 miles out and back).

Today all that remains of the town of Graham are a few remnants of the mill. The Catwalk, however, has become a national scenic trail. Long after the town closed down and the pipelines had fallen in disrepair, the Civilian Conservation Corps, a public works project enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in response to The Great Depression, rebuilt the catwalk. Amazingly, some of the original eighteen-inch pipes provide support for the present structure. The Catwalk today is approximately a 1.1 mile hike from trail head to the end (2.2 miles out and back).

Note: According to this Forest Service web page, the area is undergoing some restoration, perhaps as a result of recent flooding in the area.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Military History Monday: Quattlebaum Military Service

Today’s Military History article continues the story of the Quattelbaum (Quattlebaum) family whose American progenitor, Petter Quattelbaum, arrived in America in October of 1736 (see this past week’s Surname Saturday article here).

Today’s Military History article continues the story of the Quattelbaum (Quattlebaum) family whose American progenitor, Petter Quattelbaum, arrived in America in October of 1736 (see this past week’s Surname Saturday article here).

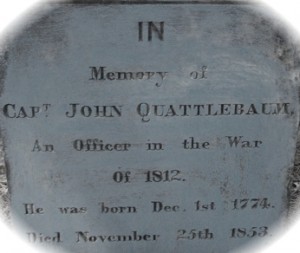

Johannes Quattelbaum, son of Petter, had seen action in the Revolutionary War, serving under Brigadier General Francis Marion, a.k.a. the “Swamp Fox”. His son John was born on December 1, 1774 in the Saxe Gotha Township, two miles north of present day Leesville, South Carolina. After the war Johannes moved his family to a Dutch settlement on Sleepy Creek, but John returned to his birthplace and married Sarah Weaver on August 5, 1798.

John and Sarah Quattelbaum had five children together before Sarah died on January 6, 1809. John was left with five young children to raise and the following year he married Metee Burkett, daughter of a fellow soldier who had fought alongside his father Johannes. He and Metee had four sons.

John and Sarah Quattelbaum had five children together before Sarah died on January 6, 1809. John was left with five young children to raise and the following year he married Metee Burkett, daughter of a fellow soldier who had fought alongside his father Johannes. He and Metee had four sons.

Sometime in 1809 John moved his family to a place on Lightwood Creek, about four miles south of Leesville, where he would establish mill operations: a flour mill, grist mill and lumber mill. There he gained a reputation as an industrialist who also manufactured cotton gins and rifles. The development of the last two industries were especially well-timed and profitable – demand for the cotton gin was high and the Quattelbaum rifle was well-known and sold throughout the country.

After receiving a commission as captain of his local militia company, John served during the War of 1812 with Lieutenant Colonel Rowe and the South Carolina Militia in defense of Charleston.

According to family history (Quattlebaum: A Palatine Family in South Carolina), “Captain Quattelbaum was a man of forceful character. He had positive opinions and expressed them readily. His integrity and devotion to duty gained him the respect of all who knew him.” John had been educated entirely in the German language, but would later acquire the English language.

On December 9, 1840, Metee died and near the end of his life John lost his eyesight and lived with his son, General Paul Quattlebaum, until he died there on November 25, 1853.

Brigadier General Paul Quattlebaum

Paul Quattlebaum was born on July 8, 1812 and at the age of three the family moved to the location where the mill operations were established. Perhaps a reflection of his father’s integrity and influence, Paul distinguished himself early in both military and public service. At the age of eighteen he was elected captain of his militia company. On September 3, 1835 he married Sarah Caroline Jones, widow of Samuel Prothro, and the daughter of Colonel Mathias Jones.

Just a short time after his marriage, the governor requested that Paul raise a company of volunteers to fight the Seminole Indians in Florida; he was again elected captain of the company. The following year his company was mustered into federal service in Georgia as part of the First Regiment, Infantry, South Carolina Volunteers. Their campaign in Florida was successful and upon his return home, Captain Quattlebaum was promoted to Colonel of the 15th Regiment, 3rd Brigade, South Carolina Militia in 1839.

When his boyhood friend, Brigadier General James H. Hammond, ascended to the governorship of South Carolina, Colonel Quattlebaum replaced him and was promoted to Brigadier General in 1843 and served in that position for ten years. Paul Quattlebaum was a busy man – not only serving in the military but in public service to his state and community.

When his boyhood friend, Brigadier General James H. Hammond, ascended to the governorship of South Carolina, Colonel Quattlebaum replaced him and was promoted to Brigadier General in 1843 and served in that position for ten years. Paul Quattlebaum was a busy man – not only serving in the military but in public service to his state and community.

Paul was many things it seems, including industrialist, following in John’s footsteps. He established a successful lumber mill operation – installing perhaps the first water-turbine wheel and the first circular saw to be used in the state. He improved upon John’s flour mill and Quattlebaum flour was marketed throughout South Carolina. The mill would also later furnish flour for the Confederate Army.

The Quattlebaum rifle continued to be manufactured as well, its reputation maintained by Paul’s leadership and oversight. It is believed that General Quattlebaum introduced the first percussion-cap locks in the state, mounted by on gun barrels made in his factory. Flint and steel locks were made obsolete by this innovation and the rifles were used by the Confederate Army.

From 1840 to 1843 he served as a state representative and from 1848 to 1851 as a state senator. In the 1830’s he had been a member of the short-lived Nullifier Party which supported states rights to the extent they believed that federal laws could be ignored (nullified). In line with advocating states rights, Paul later became a secessionist – as both a member of the Secession Convention and signing the Ordinance of Secession.

Paul Quattlebaum, however, would be precluded from field service during the Civil War due to a back injury and his advanced age. He did provide counsel to the Confederate Army and took a small part in defending the area around Columbia during the war. His home, as a signer of the Ordinance of Secession, was targeted for destruction by fire. The major in charge of carrying out the attack, personally set fire throughout the house while his men ransacked. However, the family’s slaves were able to help the family save the house.

Paul Quattlebaum died at the age of seventy-eight years in 1890. Two of his sons, Paul Jones and Theodore Adolphus served during the Civil War, both noted for distinguished and historic service.

Theodore Adolphus Quattlebaum

Theodore was born on May 11, 1842 and on January 1, 1860 entered the Arsenal Academy in Columbia to begin his military career. By the following January, it appears he had transferred to the Citadel in Charleston because he was on hand for what came to be considered the first shots of the Civil War (although it didn’t officially start for another three months).

South Carolina had just seceded a few weeks before and on January 9, 1861 Citadel cadets fired upon the Star of the West, a civilian steamship which had been hired by the federal government to deliver supplies to Fort Sumter. While the ship didn’t suffer serious damage, the captain decided it best to abandon the mission.

Theodore left the Citadel and enlisted as a private in Company K, 20th Regiment, Infantry under the command of Captain W.D.M. Harmon on December 31, 1861. By April of 1862 he had been promoted to second sergeant and steadily moved up the ranks until his promotion to lieutenant in 1864. Company K was engaged in fighting around Averysborough, North Carolina in 1865 at the Battle of Smith’s Farm.

Theodore left the Citadel and enlisted as a private in Company K, 20th Regiment, Infantry under the command of Captain W.D.M. Harmon on December 31, 1861. By April of 1862 he had been promoted to second sergeant and steadily moved up the ranks until his promotion to lieutenant in 1864. Company K was engaged in fighting around Averysborough, North Carolina in 1865 at the Battle of Smith’s Farm.

Although the battle ended as a draw, Lieutenant Theodore Adolphus Quattlebaum was mortally wounded on March 16, 1865 and died the following day. He had been fighting a rear guard action and covering the retreat of General Joseph E. Johnson when he was felled. His body was buried in a marked grave by his body servant and later his remains were transferred to the family cemetery in Lexington County, South Carolina.

Several other members of the Quattlebaum family served during the Civil War. In fact, according to Ancestry.com, there were forty-seven Quattlebaums who served the Confederacy – none in the Union Army, however. This family, with German roots, was Southern to the core.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Surname Saturday: Quattelbaum

For the first two generations after arriving in America, this German family from the Palatinate region, spelled their surname “Quattelbaum” but eventually settled on a slightly different spelling as “Quattlebaum”.

The second part of the name, “baum”, means “tree” in German. There are a couple of theories as to what “quattel” means, however. One theory is that “quattele” may have meant “quail” and the other that perhaps quattel was a fruit of the apple or quince family. In his family history, Quattlebaum: A Palatine Family in South Carolina, Paul Quattlebaum thought perhaps the fruit might have been more plum-like.

The quattel was thought to have been a “slow-growing tree, so slow-growing that the planter seldom lived to reap the fruit from the tree he planted. Hence, a man was said to ‘plant his quattels’ when he did something for posterity.”

Petter Quattelbaum

It is believed that all Americans who bear the Quattlebaum surname descend from Petter Quattelbaum (notice the different spelling), who arrived at the Port of Philadelphia on October 19, 1736. Of those who arrived that day from the Palatinate, Petter Quattelbaum was the second name on the list of those who not only swore an oath of allegiance to their new country, but also renounced citizenship of their former homeland.

Petter’s wife, Anna Barbara, three daughters (Gertraud, Maria Catherina and Anna Barbara), possibly son Mathias and his mother Maria made the journey with him. A pattern had developed as families from the Palatinate region began to immigrate to America, where they settled in New York, Pennsylvania or the Carolinas. Later generations migrated southward from Pennsylvania just before the Revolutionary War to Virginia and North or South Carolina. From the Carolinas those same people groups would venture farther out into new frontiers, first Alabama, Mississippi and Louisiana, and then on to places like Texas and Arkansas or the far west.

Petter’s wife, Anna Barbara, three daughters (Gertraud, Maria Catherina and Anna Barbara), possibly son Mathias and his mother Maria made the journey with him. A pattern had developed as families from the Palatinate region began to immigrate to America, where they settled in New York, Pennsylvania or the Carolinas. Later generations migrated southward from Pennsylvania just before the Revolutionary War to Virginia and North or South Carolina. From the Carolinas those same people groups would venture farther out into new frontiers, first Alabama, Mississippi and Louisiana, and then on to places like Texas and Arkansas or the far west.

In 1739 Petter’s name appeared on a petition for a road in Berks County and in 1742 his son Johannes was born in Williams Township (now Lehigh County). At some point, however, Petter and his family returned to Philadelphia, Paul Quattlebaum surmising that many Palatines were skilled artisans and that perhaps an urban vs. a frontier environment was more profitable for him and his family.

About ten years after the family’s arrival in America, Petter’s daughters began to marry, but before daughter Anna Barbara was married in 1749, Petter died on January 14, 1748. His death record was the second one to be entered into the Record Book of the First Reformed Church of Philadelphia. At the time of his death, he left behind Anna Barbara his wife and nine children. One month following his death the youngest child, two-year old Johanna, also died.

According to Paul Quattlebaum, her record of death was the last of that family’s to appear in Pennsylvania as the family headed south to Virginia. By the time of the Revolutionary War three of his sons, Mathias, Johannes and Peter, were living in what was called the Dutch Fork part of South Carolina, an area populated with German-Swiss families.

Johannes Quattelbaum

Johannes settled in an area south of where Mathias and Peter had remained. His first son, John, was born on December 1, 1774. In March of 1778 the South Carolina General Assembly adopted a new constitution and Johannes’ name appeared on the jury list for Saxe Gotha, the township where he lived in the Orangeburg District.

At that point in time, however, there had been little or no fighting in that part of the state. As the war escalated, it became clear that soldiers were needed to defend their way of life and Johannes joined the fight, serving under Brigadier General Francis Marion, a.k.a. the “Swamp Fox”. Another soldier he served with, Thomas Burkett, would later become son John’s father-in-law when he married Meta Burkett.

Following the war, Johannes purchased land and was part of a Dutch settlement on Sleepy Creek and Little Stevens Creek. After his first wife died, he remarried at some point and perhaps had two more boys and two girls. While it is unclear exactly when he died, he deeded land to his son George on February 16, 1813. Since his name didn’t appear on the 1820 census, Johannes Quattelbaum died sometime between 1813 and 1820.

The next three generations following Johannes Quattelbaum – that of his son John, grandson Paul and great grandson Theodore Adolphus – were highlighted with distinguished military service. I’ll write more on the lives of these three men and their military service, spanning from the War of 1812 through the Civil War, in Monday’s Military History article.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Feisty Females: Ida Bell Wells-Barnett

Ida Bell Wells was the oldest daughter of James and Lizzie Wells, born in slavery (temporarily) on July 16, 1862 in Holly Springs, Mississippi. Less than six months later, all slaves were set free by Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation. James was a master carpenter and Lizzie, a deeply religious woman, was a cook for the Bolling family.

Ida Bell Wells was the oldest daughter of James and Lizzie Wells, born in slavery (temporarily) on July 16, 1862 in Holly Springs, Mississippi. Less than six months later, all slaves were set free by Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation. James was a master carpenter and Lizzie, a deeply religious woman, was a cook for the Bolling family.

Following the Civil War, Ida’s parents were both active in the Republican Party and James, as a member of the Freedmen’s Aid Society, helped to found Shaw University (now known as Rust College), a black liberal arts school in Holly Springs. Ida had been well-educated, but while away during the summer of 1878, her life changed drastically when a yellow fever epidemic swept through Holly Springs.

James and Lizzie and one of Ida’s siblings died, leaving Ida to care for her remaining siblings. She dropped out of school but eventually found a job as a teacher to support her family. In 1882 she and three of her youngest siblings moved to Memphis, Tennessee to be near other family members. Ida taught school and also continued her education at Fisk University.

James and Lizzie and one of Ida’s siblings died, leaving Ida to care for her remaining siblings. She dropped out of school but eventually found a job as a teacher to support her family. In 1882 she and three of her youngest siblings moved to Memphis, Tennessee to be near other family members. Ida taught school and also continued her education at Fisk University.

Following in her father’s footsteps, Ida became an activist for civil rights, as well as a teacher, journalist, crusader against lynching and a suffragist. In 1884 an incident occurred on a Chesapeake & Ohio train to Nashville when she was asked by the conductor to give up her first-class seat for a white man. The practice of segregation had been outlawed with the 1875 Civil Rights Act, but railroads often skirted the law and segregated their passengers.

On principle, Ida refused to move to the so-called “Jim Crow” car – this incident occurring over seventy years before Rosa Parks refused to give up her bus seat. As the conductor attempted to forcibly remove her from her seat, Ida bit the man’s hand. She related the details in her autobiography:

I refused, saying that the forward car [closest to the locomotive] was a smoker, and as I was in the ladies’ car, I proposed to stay. . . [The conductor] tried to drag me out of the seat, but the moment he caught hold of my arm I fastened my teeth in the back of his hand. I had braced my feet against the seat in front and was holding to the back, and as he had already been badly bitten he didn’t try it again by himself. He went forward and got the baggageman and another man to help him and of course they succeeded in dragging me out.

Upon her return to Memphis, Ida employed an attorney, sued the railroad and won a $500 settlement – only to have it overturned by the Tennessee Supreme Court. Ida began to write articles which were published in various black newspapers and periodicals. She would later become the owner of the Memphis Free Speech and Headlight, a larger platform from which to advance the causes she was fighting for.

She openly criticized the Memphis school system for its lack of funding for poor schools and was dismissed by the Memphis school board in 1891. Thereafter, she became a full-time journalist and activist. In 1892 three black men had opened a grocery store in Memphis and became successful enough to begin drawing customers away from another store (white-owned) in the neighborhood. After a confrontation with whites, the three men were arrested and taken to jail, only to have the jail overrun and the three African-Americans lynched.

Ida’s efforts to outlaw lynching were met with anger by white Tennesseans, and the offices of the Free Speech were destroyed. Yet, Ida was undeterred by their threats and continued to campaign for anti-lynching laws (which were never passed). Ida had been traveling in the South researching the practice of lynching when her newspaper offices were destroyed. She received death threats warning her against returning to Memphis, but continued to travel and lecture, both at home and abroad, with her anti-lynching message.

In 1898 she led a protest in Washington, D.C., calling on President William McKinley to act. That same year she also married attorney Ferdinand L. Barnett of Chicago. They had four children together, but Ida struggled to balance her home and activist, eventually forcing her to curtail her travel and speaking schedules.

Even though she was never able to compel legislators to enact anti-lynching laws, she fought on. In 1896 she founded the National Association of Colored Women and in 1909 helped to found the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). She and Mary Church Terrell, another civil rights activist, were the only two women to sign the petition which led to the organization’s founding.

She joined the national suffragist movement, integrating it by refusing to remain at the rear of a 1913 march in Washington, D.C. In 1928 Ida began writing her autobiography, Crusade for Justice, but never finished the book – the book ended in the middle of a sentence and her daughter later edited and published it posthumously.

In her final year Ida was running for the Illinois State Senate and kept up a demanding and busy schedule. Even though she had been a tireless crusader most of her life, some of the last pages she wrote in her journal were filled with doubts about what she had accomplished during her lifetime: “All at once the realization came to me that I had nothing to show for all those years of toil and labor.”

Ida Bell Wells-Barnett died on March 25, 1931 of kidney failure, active until her last days. She had once said: “I felt that one had better die fighting against injustice than to die like a dog or a rat in a trap.”

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!