Ghost Town Wednesday: Proffitt, Texas

This ghost town in Young County, Texas was named after a part-time Methodist minister and storekeeper from Tennessee, Robert S. Proffitt, who migrated to Hood County, Texas in 1852 and then moved to Young County in the early 1860’s. Robert and his sons were cattle ranchers and settled in area along the Brazos River and Elm Creek near Fort Belknap.

This ghost town in Young County, Texas was named after a part-time Methodist minister and storekeeper from Tennessee, Robert S. Proffitt, who migrated to Hood County, Texas in 1852 and then moved to Young County in the early 1860’s. Robert and his sons were cattle ranchers and settled in area along the Brazos River and Elm Creek near Fort Belknap.

In 1862 the town was founded and Robert’s son John later donated land for a cemetery, a Methodist Episcopal church, a school and a Masonic Lodge following the Civil War. The area was perfect for cattle raising, but was plagued with Indian depredations. Before the Civil War ended, a horrible event occurred on Elm Creek on October 31, 1864. It came to be known as the Elm Creek Raid.

In 1862 the town was founded and Robert’s son John later donated land for a cemetery, a Methodist Episcopal church, a school and a Masonic Lodge following the Civil War. The area was perfect for cattle raising, but was plagued with Indian depredations. Before the Civil War ended, a horrible event occurred on Elm Creek on October 31, 1864. It came to be known as the Elm Creek Raid.

This area of Texas is of particular interest to me since my great-great-grandmother Louisa Elizabeth “Eliza” Boone Hensley Brummett Dodson (there’s a story there I assure you!) and her family were ranchers in Jack County, east of Young County during this same period. Her obituary stated that she lived through those dangerous times of Indian depredations long before nearby Fort Richardson was established in that county. “She participated in the dangers and the privations of these formative days, attending the winning of the frontier when courage and determination were required in such large measure of those who could survive the trying ordeals of such a life.”

This area of Texas is of particular interest to me since my great-great-grandmother Louisa Elizabeth “Eliza” Boone Hensley Brummett Dodson (there’s a story there I assure you!) and her family were ranchers in Jack County, east of Young County during this same period. Her obituary stated that she lived through those dangerous times of Indian depredations long before nearby Fort Richardson was established in that county. “She participated in the dangers and the privations of these formative days, attending the winning of the frontier when courage and determination were required in such large measure of those who could survive the trying ordeals of such a life.”

On the day of the 1864 raid, several hundred Kiowa and Comanche Indians attacked settlers. Ten people were killed that day, including one young lady who was scalped, and the son of a black slave. Five soldiers belonging to a Confederate company were killed while pursuing the Indians. Two women and five children were also taken captive, but by the end of 1865 all had been returned or rescued.

Another raid occurred on July 17, 1867 in the same area. Three young men were herding cattle and an Indian party came upon them, killed and scalped them. One of the young men was Robert Proffitt’s son, Patrick Euell Proffitt. Patrick and the other men, Rice Carlton and Reuben Johnson, all nineteen years old, were buried in a common grave which is today commemorated with an historical marker. Their grave was the first in what came to be called the Proffitt Cemetery.

John Proffitt, Robert’s son, started a freighting business and later opened a store in 1894. In 1880 a post office was established and later a Baptist church was also built. The town thrived for several years, although by 1925 the post office was closed, the same year John Proffitt died. The town’s population dwindled down to about fifty residents until in 1960 it rose to one hundred and twenty-five. County maps of the 1980’s, however, indicated a rural settlement near Elm Creek that consisted only of a church, community center and cemetery.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Tombstone Tuesday: Simpson Socrates Nix (and a little Civil War history)

Simpson Socrates Nix was born on April 10, 1841 in Weakley County, Tennessee to parents Riley and Mary Ann (Alexander) Nix. Riley and Mary Ann were born in North Carolina, both in 1820, and they married on October 17, 1838 in Henry County, Tennessee. Their family was enumerated in Weakley County in 1850, but by 1860 they had relocated to Calloway County, Kentucky.

Simpson Socrates Nix was born on April 10, 1841 in Weakley County, Tennessee to parents Riley and Mary Ann (Alexander) Nix. Riley and Mary Ann were born in North Carolina, both in 1820, and they married on October 17, 1838 in Henry County, Tennessee. Their family was enumerated in Weakley County in 1850, but by 1860 they had relocated to Calloway County, Kentucky.

According to The History of Jasper County, Missouri, Riley was a farmer and also involved in local politics, serving as sheriff and public administrator. A posting at Find-A-Grave seems to indicate that Riley’s father was a slave owner in Tennessee, but it’s unclear whether Riley owned slaves. He and his family did, however, live in a part of Kentucky that was more sympathetic to the Southern slave states.

According to The History of Jasper County, Missouri, Riley was a farmer and also involved in local politics, serving as sheriff and public administrator. A posting at Find-A-Grave seems to indicate that Riley’s father was a slave owner in Tennessee, but it’s unclear whether Riley owned slaves. He and his family did, however, live in a part of Kentucky that was more sympathetic to the Southern slave states.

This article was enhanced, complete with sources, and published in the April 2018 issue of Digging History Magazine. The entire issue was devoted to the Civil War. Should you prefer to purchase the article only, contact me for more information.

This article was enhanced, complete with sources, and published in the April 2018 issue of Digging History Magazine. The entire issue was devoted to the Civil War. Should you prefer to purchase the article only, contact me for more information.

I invite you to check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Surname Saturday: Noel

Noel is an English surname with French origins, according to most sources. Some Noel family historians believe the name may have originated among the Gallic tribes of Normandy in northern France, possibly those who lived in Noailles (pronounced no-ay). In France the name would have appeared as “Noël” and often associated with a person who was born on Christmas Day.

Noel is the French word for Christmas, with origins dating back before the Normandy invasion of 1066. Apparently a common practice, the Internet Surname Database points out that names like Easter and Midwinter were likewise associated with either holidays or seasons of the year. The spelling was slightly changed when it appeared in England in the mid-twelfth century – Robert fitz Noel.

French Noel family historians point out that Frenchmen bearing the surname Noël who came to America had their names recorded as “Noel” by the English. In England the name may have been associated with someone whose duty as a servant was to provide a yule log to his master.

French Noel family historians point out that Frenchmen bearing the surname Noël who came to America had their names recorded as “Noel” by the English. In England the name may have been associated with someone whose duty as a servant was to provide a yule log to his master.

Spelling variations include: Noel, Noël, Noell, Nole, Nowell, Naull and others. The name is not exclusively French or English, nor necessarily a Christian name either. While researching this surname I came across Abraham Noel who was of Jewish ancestry and a 1904 Russian immigrant. Based on historical New York immigrant passenger lists, Germany ranks the highest (93), followed by France (73).

Edmond Favor Noel

Edmond Favor Noel was born on March 4, 1856 to parents Leland and Margaret (Sanders) Noel in rural Holmes County, Mississippi. According to The Official and Statistical Register of the State of Mississippi, his ancestors were probably French Huguenots (Protestants) who fled to England. Large numbers of this persecuted religious group began to flee France in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries.

From England his ancestors came to settle in Essex County, Virginia in 1680. The Noel family remained there until Leland migrated to Mississippi. He later served in the Confederate Army, was captured by the Union Army in 1863 and while imprisoned lost his eyesight. He remained blind the rest of his life.

Edmond’s education was irregular until he entered high school in Louisville, Kentucky. Although he never attended college, he read law under his uncle, Major D.W. Sanders, a Louisville attorney. Before the American Bar Association began lobbying in the late nineteenth century to discontinue the practice of “reading the law” versus attending an accredited law school, this had been a common practice in America since early colonial days.

Edmond’s education was irregular until he entered high school in Louisville, Kentucky. Although he never attended college, he read law under his uncle, Major D.W. Sanders, a Louisville attorney. Before the American Bar Association began lobbying in the late nineteenth century to discontinue the practice of “reading the law” versus attending an accredited law school, this had been a common practice in America since early colonial days.

After passing an open examination in court, Edmond was admitted to the bar in March of 1877. He returned to Mississippi and opened a law practice. During the Spanish-American War he served as a captain in the Second Mississippi Volunteer Infantry. Following his admittance to the practice of law, he had pursued elective office, variously serving in the state legislature, as District Attorney of the Fifth Judicial District and as state senator.

He unsuccessfully ran for governor of Mississippi in 1903. In 1907 he was elected governor and served for one term. He married his second wife, Alice Tye Neilson, in 1905. Interestingly, her ancestry included her great uncle Nathaniel Alexander, one of the first governors of North Carolina. Her great-grandfather Abraham Clarke was one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence.

After leaving office in 1912, Noel returned to his law practice in Lexington. He remained active in politics, making an unsuccessful run for national office (Senate) in 1918. In 1920 he was elected to the Mississippi State Senate and served there until his death on July 30, 1927.

Edmond Noel’s grave stone has to be one of the most interesting ones I’ve ever seen and a bonanza for genealogists. Although succinct, quite a bit of his and Alice’s genealogical data is engraved on the stone.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Far-Out Friday: Honeymoon In The Corn Field

Their May-December marriage made headlines in early June of 1946, right along with worries over sky-rocketing milk prices (up one cent per quart!) and possible meat and bread shortages. One newspaper article noted that mothers were thinking about feeding their children cake instead of bread that night (let them eat cake!). However, for Mattie Large and her teenage husband, their marriage wasn’t such a big deal to them in the hills of eastern Kentucky near Louisa. It did raise eyebrows around the country though.

Their May-December marriage made headlines in early June of 1946, right along with worries over sky-rocketing milk prices (up one cent per quart!) and possible meat and bread shortages. One newspaper article noted that mothers were thinking about feeding their children cake instead of bread that night (let them eat cake!). However, for Mattie Large and her teenage husband, their marriage wasn’t such a big deal to them in the hills of eastern Kentucky near Louisa. It did raise eyebrows around the country though.

Did you enjoy this article snippet? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. This article has been updated and is available in the July-August 2021 issue of the magazine.

Did you enjoy this article snippet? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. This article has been updated and is available in the July-August 2021 issue of the magazine.

Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-90 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads, just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? Samples available here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Wild Weather Wednesday: Yet Another 1913 Historic Storm

From beginning to end, the year 1913 was a meteorologically-challenging year. Earlier this year, “Wild Weather Wednesday” articles covered two 1913 historic weather events: The Great Flood of 1913 (Part One and Part Two) and The White Hurricane. On July 10, 1913 the highest temperature ever recorded in the United States occurred in Death Valley – 134 degrees.

From beginning to end, the year 1913 was a meteorologically-challenging year. Earlier this year, “Wild Weather Wednesday” articles covered two 1913 historic weather events: The Great Flood of 1913 (Part One and Part Two) and The White Hurricane. On July 10, 1913 the highest temperature ever recorded in the United States occurred in Death Valley – 134 degrees.

That year would end with an historic blizzard which buried the eastern slope of Colorado in early December. As the Daily Journal of San Miguel County reported on December 1, snow was “general throughout Colorado”, but the eastern slope would take the brunt of the storm. Days later the Steamboat Pilot reported their part of the state had entirely escaped the storm.

That year would end with an historic blizzard which buried the eastern slope of Colorado in early December. As the Daily Journal of San Miguel County reported on December 1, snow was “general throughout Colorado”, but the eastern slope would take the brunt of the storm. Days later the Steamboat Pilot reported their part of the state had entirely escaped the storm.

This article is no longer available for free at this site. It was re-written and enhanced, complete with footnotes and sources and has been published in the February 2018 issue of Digging History Magazine. Should you prefer to purchase the article only, contact me for more information.

This article is no longer available for free at this site. It was re-written and enhanced, complete with footnotes and sources and has been published in the February 2018 issue of Digging History Magazine. Should you prefer to purchase the article only, contact me for more information.

I invite you to check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

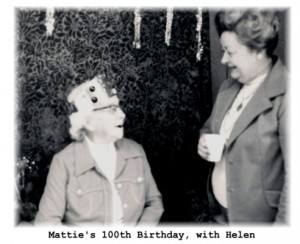

Tombstone Tuesday: Mattie Grace Grob Large (1892-1992)

Some Tombstone Tuesday articles just beg to be written because the subject lived such a long and purposeful life. Today’s article is one of those.

Some Tombstone Tuesday articles just beg to be written because the subject lived such a long and purposeful life. Today’s article is one of those.

Mattie Grace Grob was born on January 16, 1892 in Leavenworth, Kansas to parents Mathias and Martha (Kuellmer) Grob. Mathias was born in Germany in 1849 and immigrated with his parents to Ohio when he was four years old. Martha was the daughter of German immigrants and was born in Ohio in 1854. Mathias and Martha married on November 4, 1879 and to their marriage were born nine children, six of them living to adulthood, although their oldest child Elizabeth died at the age of thirty-six.

Mathias and Martha migrated to Kansas in 1883, where Mathias engaged in farming. His obituary noted that he was a self-made man, well-informed and a prosperous land owner. Early in adulthood he had become a Christian and loved to attend church. He was a generous person who diligently studied the Bible, able to hold forth on perplexing issues. In reading about Mattie’s life, it’s obvious her parents and their faith provided a great example to follow.

Mathias and Martha migrated to Kansas in 1883, where Mathias engaged in farming. His obituary noted that he was a self-made man, well-informed and a prosperous land owner. Early in adulthood he had become a Christian and loved to attend church. He was a generous person who diligently studied the Bible, able to hold forth on perplexing issues. In reading about Mattie’s life, it’s obvious her parents and their faith provided a great example to follow.

Mattie married Leo Seth Large on July 28, 1914. According to family historians, Leo’s father wasn’t around much during his childhood. His mother struggled to support her own children as well as those from James Large’s first marriage. In 1916 his mother disappeared and Leo and Mattie took care of some of the younger children. Perhaps this is why they had only two children of their own: Helen Kathryn (1916) and Leo Harvel (1918).

Leo was a truck farmer in Leavenworth County, Kansas, well known and respected by the community. After his retirement from farming, Leo and Mattie lived in DeSoto (Johnson County), Kansas. Mattie was a telephone operator for the city of DeSoto for several years. She was an active member of the local Methodist Church, volunteering her time to prepare meals for church dinners. She was also an expert gardener and a seamstress.

Leo was a truck farmer in Leavenworth County, Kansas, well known and respected by the community. After his retirement from farming, Leo and Mattie lived in DeSoto (Johnson County), Kansas. Mattie was a telephone operator for the city of DeSoto for several years. She was an active member of the local Methodist Church, volunteering her time to prepare meals for church dinners. She was also an expert gardener and a seamstress.

Leo died in 1962 of lung cancer and was buried in the DeSoto Cemetery. All through her life it appears Mattie Grace kept busy. I found several accounts of people who posted remembrances at Find-A-Grave. Mattie made such an impression on them and their memories are still vivid.

Like her father, she was a generous person, one friend remembering “you never left her house empty handed, whether it was a magazine, jar of jelly or a plant from her flower bed.” Her children, six grandchildren and eleven great-grandchildren adored her.

Mattie Grace Grob Large had a long and purposeful life. She celebrated her one hundredth birthday in early 1992 and was residing in a Topeka nursing home. She passed away a couple of months shy of her one hundred and first on November 8, 1992. Some of the stories I write make me wish I’d known the person. Mattie is one of those people and I hope you enjoyed her story.

Mattie Grace Grob Large had a long and purposeful life. She celebrated her one hundredth birthday in early 1992 and was residing in a Topeka nursing home. She passed away a couple of months shy of her one hundred and first on November 8, 1992. Some of the stories I write make me wish I’d known the person. Mattie is one of those people and I hope you enjoyed her story.

I was actually researching another husband and wife, Abraham and Sarah Large, when I came across Mattie’s story. In this holiday season of giving and goodwill, it seemed appropriate to tell Mattie’s heartwarming story instead. I ran across another Mattie Large while researching Mattie Grace. I’ll tell her story on Far-Out Friday – a true story you just can’t make up!

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Surname Saturday: Butter (and a little apple history)

Butter

Today’s surname is also a common word and another one which presents a research challenge, but with an interesting historical twist – the story of an apple. According to immigration passenger lists, people with the Butter surname, or some variation thereof, came from Ireland, England, Scotland and Germany. 1920 census records indicated a substantial number of the Butter family in Texas, as well as New York, Pennsylvania, Michigan and Tennessee.

The theories as to its origins are as follows:

Forbears: This web site notes that the surname Butter (or some variation of it, and there are many) is the 33,215th most common in the world. The highest incidences of the name today occur, surprisingly, in Nigeria, Germany and the Netherlands, with the United States ranked fourth. According to Forbears, the surname is a nickname: “the butur”; “Buture, the bittern”; “Botor, a bustard” (Source: Dictionary of English and Welsh Surnames). In 1273 the name John le Butur of Cambridgeshire was listed on the Hundred Rolls, as well as John Botere of Huntingsdonshire. In 1581 Richard Butter was on the rolls of the University of Oxford.

Internet Surname Database: This web site concurs with Forbears in regards to a nickname origin and elaborates a bit more. The nickname would be for someone having a certain vocal characteristic the call of a bittern, a wading bird in the heron family. Both the Middle English word “botor” and the Old French word “butor” both mean bittern. Another observation is an Old English word “butere” which meant “butter” and referred to an occupational name for a dairyman or someone who sold butter or ran a buttery.

House of Names: In Scotland the name was first seen among the Pictish clans and the family lived in Perth and Fife counties. One village was named “Buttergask” or “Buttercask” in the Ardoch parish.

ScotClans: Butter was the name of an old family in Perthshire. The name Adam Butir was recorded in 1331 and William Butyr and Patrick Butirr are found in 1360 records.

4Crests: The surname was as official name, meaning “at the buttery” or one who kept butter, or a store for liquor. Richard of the Bottery was mentioned in a 1399 record. John Butterey married Elizabeth Burnell in 1531, and a daughter of John Buttereye was baptized in 1669 in London.

Variations of this name include: Butter, Butters, Butterlaw, Butterwick, Butterworth, Butterton, Buttar, Buttars, Butere, Putter, Buttry, Batter, and many, many more.

When did the Butter (or Butters) family make its way to America? According to The Genealogical Registry of the Butters Family, published in 1896, the name first appeared following the arrival of Scottish prisoners, referring to them as “romantic young followers of Charles II” who had been captured at Dunbar and Worcester by Cromwell and sent to the colonies as indentured servants.

When did the Butter (or Butters) family make its way to America? According to The Genealogical Registry of the Butters Family, published in 1896, the name first appeared following the arrival of Scottish prisoners, referring to them as “romantic young followers of Charles II” who had been captured at Dunbar and Worcester by Cromwell and sent to the colonies as indentured servants.

Tradition holds that in the early days of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, three Butter brothers came from Scotland: John, Isaac and William Butter. One was said to have gone off somewhere and never heard from again, and another was captured by Indians, and upon his escape returned to Scotland. The records for John and Isaac were so sparse that the nineteenth century family genealogists concluded that William Butter, who settled in Woburn, Massachusetts was likely the progenitor of their family in America.

The Butters Apple

According to the family history cited above, the area where William settled and many of his descendants remained for over two hundred years was an area known as “Butters Row District”, situated in a new town near Woburn called Wilmington. A map included in the Butter history book lists the following people who lived in the era continuously from 1665 to 1895:

William Butters

James Butters

Abiel Butters

Samuel Butters

John Butters

Lorenzo Butters

Walter Butters

Oliver Butters

Simeon Butters

In the same district was a school called the Butters Row School. In the middle of all of these Butters family members and their properties is a landmark simply called “Apple Tree.” Why would a map like this include a prominently marked “Apple Tree”. This particular apple tree was planted by William Butters (1711-1784) who was the grandson of William Butter, the immigrant. The tree had been transplanted from a neighboring farm in Wilmington.

The tree was situated near William’s house and as the tree grew it attracted a large number of birds, namely woodpeckers. The apple was first called the “Woodpecker” or “Pecker”, but also known as the “Butters Apple”. The tree flourished and produced fruit for a number of years before Deacon Samuel Thompson discovered it while surveying the Middlesex Canal.

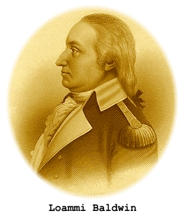

Thompson mentioned his discovery to canal engineer Loammi Baldwin, who was so impressed with the apple that he visited the Butters farm and obtained his own cuttings for transplantation near his home in Woburn. He gave cuttings to friends and later the apple variety was named after him.

Baldwin, a Revolutionary War veteran who crossed the Delaware with Washington, was a scientist and civil engineer, who also happened to be (appropriately) the second cousin of Johnny Appleseed. Baldwin apples were a hearty and flavorful variety used for making pies and hard apple cider. The bright-colored fruit is a winter apple and easily shipped. Harvested in October, they can be stored for several months.

Baldwin, a Revolutionary War veteran who crossed the Delaware with Washington, was a scientist and civil engineer, who also happened to be (appropriately) the second cousin of Johnny Appleseed. Baldwin apples were a hearty and flavorful variety used for making pies and hard apple cider. The bright-colored fruit is a winter apple and easily shipped. Harvested in October, they can be stored for several months.

The Baldwin became the most popular apple grown in New England. In 1833 the New American Orchardist noted that “no apple in the vicinity of Boston is so popular as this, at the present day.” By the mid-nineteenth century the apple was seen in other states like New York and Pennsylvania.

The Baldwin became the most popular apple grown in New England. In 1833 the New American Orchardist noted that “no apple in the vicinity of Boston is so popular as this, at the present day.” By the mid-nineteenth century the apple was seen in other states like New York and Pennsylvania.

In 1895 the Rumford Historical Society erected a monument to the Baldwin apple near its original location in Wilmington. The inscription reads:

In 1895 the Rumford Historical Society erected a monument to the Baldwin apple near its original location in Wilmington. The inscription reads:

This monument marks the site of the first Baldwin Apple Tree found growing wild near here. It fell in the gale of 1815. The apple first known as the Butters, Woodpecker or Pecker apple was named after Col. Loammi Baldwin of Woburn. Erected in 1895 by the Rumford Historical Association.

The popularity of the Baldwin declined in the early twentieth century, however, with the introduction of the Jonathan variety. In 1934 a devastatingly cold winter in the northeast destroyed several orchards across New England. Though not as popular today, it’s still considered a good cider apple.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Feisty Females: Harriet Quimby

Her life, though short, was full of many accomplishments. Harriet Quimby was born on May 11, 1875 in Arcadia, Michigan to parents William and Usrula Quimby. The Quimbys had several children, but only Harriet and her older sister Kittie survived to adulthood. Historians note that her father was an unsuccessful farmer who left the Midwest in the early 1900’s and headed West.

Her life, though short, was full of many accomplishments. Harriet Quimby was born on May 11, 1875 in Arcadia, Michigan to parents William and Usrula Quimby. The Quimbys had several children, but only Harriet and her older sister Kittie survived to adulthood. Historians note that her father was an unsuccessful farmer who left the Midwest in the early 1900’s and headed West.

This article is no longer available on the web site. It will, however, be rewritten (complete with footnotes and sources) and included in a future issue of Digging History Magazine.

This article is no longer available on the web site. It will, however, be rewritten (complete with footnotes and sources) and included in a future issue of Digging History Magazine.

I invite you to check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

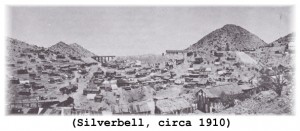

Ghost Town Wednesday: Silverbell, Arizona

There were actually two towns in Arizona with the same name, one “Silverbell” and one “Silver Bell”, situated about four miles apart. Both were mining towns, but “Silverbell” has the most colorful history.

There were actually two towns in Arizona with the same name, one “Silverbell” and one “Silver Bell”, situated about four miles apart. Both were mining towns, but “Silverbell” has the most colorful history.

According to the Arizona State Museum, the first time any mining operations were recorded in the area was in the early 1870’s when Charles O. Brown from Tucson began prospecting. Throughout the 1870’s Brown and his partners staked several claims, opened mines and built a smelter. At the time Arizona was still a territory, and it would be several years before that part of the west was tamed enough to become a full-fledged state. In that era without strong territorial authority, mining districts were established.

Miners elected a leader and recorder and committees set boundaries and enforced rules. Brown’s operations fizzled and in 1890 two English companies came to the so-called Silver Bell Mining District, but their tenure was short-lived and there was little to show for the investment.

At the turn of the century, new mining interests bought up a substantial number of claims in the district. By 1901 there was enough activity in the area to warrant the establishment of a public school, with an enrollment of seventy-five students the first year. The two communities, Pelton and Atlas Camp, although small in numbers, were enumerated for the 1900 census.

Claims were sold in 1903 to the Imperial Copper Company, and soon afterwards the town of Silverbell was established. By 1905 the population of Silverbell had reached around one thousand. In 1904 a post office was opened. Silverbell, like many towns throughout the west, including a company store and the company’s offices. The town also had a school, saloons, a Chinese bakery, barber, doctor, justice of the peace and a deputy sheriff.

Silverbell continued to expand and other businesses, including a company-owned hotel were added. There were some challenges for Silverbell, however. Good drinking water was hard to come by and had to be brought in by wagon or train. The water, stored in tanks, was piped to the town’s residents.

Another challenge for the town was its penchant for violence. Despite the presence of a lawman, the area was plagued with murders and other acts of lawlessness. Before Deputy Sheriff Joe McEven arrived three murders had already occurred. James and Barbara Sherman, authors of Ghost Towns of Arizona, wrote that Silverbell was known as the “hell-hole of Arizona.”

The lawlessness and drinking water issues bring up an interesting observation I made while researching the town’s cemetery at Find-A-Grave. At the web site there are eighty-five interments listed, and someone has taken the time to find and post each and every person’s death record. The cemetery has several young children buried there, some who died of enteritis, which I’m guessing might have been due to the lack of potable water.

The lawlessness and drinking water issues bring up an interesting observation I made while researching the town’s cemetery at Find-A-Grave. At the web site there are eighty-five interments listed, and someone has taken the time to find and post each and every person’s death record. The cemetery has several young children buried there, some who died of enteritis, which I’m guessing might have been due to the lack of potable water.

There were a few people who died of illnesses such as typhoid fever, dysentery and tuberculosis. There were miners who died in mine accidents and there were some who were killed by violence. The majority of those buried (at least those listed at Find-A-Grave who probably had grave markers) in the Silverbell cemetery were originally from Mexico it appears, although the Arizona State Museum said other ethnic groups such as Papago, Chinese and Japanese made their home in Silverbell.

In 1910 the population of Silverbell was 1,118 persons living in 327 households. There were grocers, butchers, restaurant owners, musicians, teachers, carpenters, and more – and of course, as seen in most mining towns, prostitutes. The company operated a hospital and in 1910 there was also a movie house. The town’s fortunes changed the following year, however.

In 1910 the population of Silverbell was 1,118 persons living in 327 households. There were grocers, butchers, restaurant owners, musicians, teachers, carpenters, and more – and of course, as seen in most mining towns, prostitutes. The company operated a hospital and in 1910 there was also a movie house. The town’s fortunes changed the following year, however.

By 1911 many businesses began to depart when Imperial overextended itself and declared bankruptcy. Its holdings were leased to American Smelting & Refining Company (ASARCO) and by 1919 ASARCO had acquired all of the assets of Imperial, including the railroad and smelter. The post office had closed in 1911 but was reopened in 1916.

The population of Silverbell temporarily rebounded after ASARCO assumed ownership, but by 1920 the price of copper fell and ASARCO turned their attention to other mining operations. Between 1920 and 1930 about five hundred people populated Silverbell, but by 1930 all copper mining had been shut down. In 1931 there were only about forty-five people and the post office closed for the last time in 1934. By 1954, Silverbell was totally abandoned.

ASARCO, although abandoning mining operations in Silverbell, continued to work other mines in the area. In 1954, just four miles southeast of Silverbell, they established the town of “Silver Bell”. Mining operations at the new site actually seemed to have faired better until 1984 when copper prices again plummeted. The availability of potable water and a viable sewage system again added to the challenges. Houses fell into disrepair and in the late 1980’s only a few homes and company buildings remained.

ASARCO purchased an old mine near the original Silverbell town site in 1989. It was noted in 2007, however, that the town is now abandoned with only a few company buildings, mine shafts and some junked vehicles remaining.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Tombstone Tuesday: Greenup Raney

Greenup Raney was born on August 7, 1846, according to an entry at Find-A-Grave (and his grave stone), although he could have been born anywhere from 1847 to 1849, based on various records. It appears from an 1860 census record that his mother was named Celia and he had a brother James who had been born around 1852. Greenup was eleven in 1860 on the 21st day of July.

Greenup Raney was born on August 7, 1846, according to an entry at Find-A-Grave (and his grave stone), although he could have been born anywhere from 1847 to 1849, based on various records. It appears from an 1860 census record that his mother was named Celia and he had a brother James who had been born around 1852. Greenup was eleven in 1860 on the 21st day of July.

Greenup’s father, however, is a mystery . . . and I’m not the only one scratching their head on this one. I came across several posts asking for information on Greenup’s father. For now, that remains a mystery.

Just as mysterious is what happened to Celia. After the 1860 census when she was enumerated as the head-of-household with two sons, she disappeared. She was a thirty eight year-old day laborer in 1860. Her name doesn’t appear in the 1870 census records, but a reference to her apparent demise is referenced on Greenup’s marriage record.

Greenup married Martha Ann Pointer on October 17, 1867 in Pulaski County, Kentucky. The record notes that Greenup did not know his father’s birth place, so it might be that his birth father and Celia perhaps never married. On that day, Greenup was nineteen years old which would indicate a birth year of 1848 (the 1900 census recorded August 1847). Martha Ann was a bit older, twenty-two at the time of their marriage. As to the whereabouts of either of Greenup’s parents, the remarks at the bottom of the record tell us that “groom has neither father, mother or guardian living.”

Greenup married Martha Ann Pointer on October 17, 1867 in Pulaski County, Kentucky. The record notes that Greenup did not know his father’s birth place, so it might be that his birth father and Celia perhaps never married. On that day, Greenup was nineteen years old which would indicate a birth year of 1848 (the 1900 census recorded August 1847). Martha Ann was a bit older, twenty-two at the time of their marriage. As to the whereabouts of either of Greenup’s parents, the remarks at the bottom of the record tell us that “groom has neither father, mother or guardian living.”

There is a record indicating that a Greenup Raney enlisted in Company B of Kentucky Hall’s Gap Infantry Battalion on April 16, 1865 in Stanford, Lincoln County, Kentucky. General Robert E. Lee had surrendered to General Ulysses S. Grant exactly a week earlier in Virginia.

Greenup’s service was short-lived, mustered out on July 27, 1865. Although his military service was brief, he applied for a pension on July 26, 1890. I suppose it’s also possible this might have been Greenup’s father and he was named after him, but records for anyone named Greenup Raney seem to all point to today’s subject.

Greenup’s service was short-lived, mustered out on July 27, 1865. Although his military service was brief, he applied for a pension on July 26, 1890. I suppose it’s also possible this might have been Greenup’s father and he was named after him, but records for anyone named Greenup Raney seem to all point to today’s subject.

No Civil War battles had been waged in southern Lincoln County, however the residents remained vigilant. Thus, this unit was formed to scout the area and protect it. In a book chronicling the history of Lincoln County, it was noted that the area had always been a perfect place to raise children. Most folks were farmers and there was an abundance of woods, filled with trees, plants and small animals. “The community was filled with good, decent, Christian people raising children and sharing the problems of each household.”

The children born to Greenup and Martha’s marriage were:

William Gaither (1868)

Emmaline (1869)

James Francis (1875)

Mary Elizabeth (1876)

Parlee Pearl (1879)

John (1882)

Mattie Bell (1885)

It appears the entire family remained in Pulaski County, the children also marrying spouses from the area and raising the grandchildren of Greenup and Martha there. Greenup, who went by the shortened name “Green” was a farmer. In 1900 four of their children remained in the home (Emmaline, Parlee, John and Mattie). Emmaline married later that year. By 1910, their nest was empty.

Greenup passed away on September 12, 1912 and was buried in Goforth Cemetery in Pulaski County. The grave stone appears to have been “homemade” and the date of his birth is listed as August 7 ,1846. In 1930 Martha Ann was living with her daughter Emmaline and her family, and this appears to be the last record available for her.

Lots of “Green” in Pulaski County

While researching this article, I came across a lot of males named “Green” in Pulaski County. It seems to have been a popular name. I found one other Greenup (Jones), but maybe like Greenup Raney he went by just “Green”. Not sure where the name came from but there is a Greenup County in northern Kentucky.

The most interesting “Green” name, however, was Green B. Rash (the “B” may be as in “Berry” – I’ve seen some other Kentucky men named Green Berry or Littleberry). It seems that Green Rash served with some of my kin (a Stogsdill cousin or uncle) during the Civil War – their names are listed on the 1890 Veterans Schedule in the same company.

In my research I came across more names from my own family. William G. Raney’s second marriage was witnessed by two people named Sears and Stogsdill (surnames both in my line). So, who knows – as thick as folks in that part of the world were, I might be related somehow to some of these Green fellows.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!