Surname Saturday: Lawson

The Lawson surname has “truly ancient origins”, according to The Internet Surname Database (ISD). Originating in the Holy Land, it was brought back to England and Scotland by the crusaders of the twelfth century in the form of “Lawrence”, and the baptismal name “Lawson” means “son of Lawrence”. The earliest form of Lawrence used was simply “Law” and considered an endearing name.

According to ISD, there were at least seventeen coats of arms and all could be traced back to Richard III and “The War of the Roses”. The arms suggested a “loyal person who lived by the sword, having no estates to support him.” The Lawson surname appears to have been localized in the north, specifically Yorkshire, Lancashire, Cumberland and Westmorland.

The names of Christopher and Thomas Lawson are found on a list of names of individuals living in Virginia on February 16, 1623. This was an important census, for on March 22, 1622 the Jamestown Massacre had occurred, and approximately one-third of the settlers of Jamestown were killed in a series of surprise attacks by the Powhatan Indians. Following are stories of other early and notable American Lawsons and a nineteenth century Lawson with an interesting background as an aviation pioneer and the founder of his own religion.

Epaphroditus Lawson

Epaphroditus Lawson was the son of John and Sarah Rowland Lawson. His exact date of birth is unclear – ranging from 1600 to 1610 according to most sources. It appears that Epaphroditus and his three brothers, Rowland, Richard and Christopher (not sure if this is the same Christopher mentioned above) all immigrated to America.

Epaphroditus was mentioned as a witness to a land transaction on July 20, 1633. Thereafter, there are several records indicating that Epaphroditus had extensive land holdings and business dealings. According to Ancestors of Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter, Epaphroditus had business dealings with an ancestor of President Jimmy Carter – John Carter, to whom Epaphroditus, according to his will, owed money to at the time of his death.

Epaphroditus was mentioned as a witness to a land transaction on July 20, 1633. Thereafter, there are several records indicating that Epaphroditus had extensive land holdings and business dealings. According to Ancestors of Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter, Epaphroditus had business dealings with an ancestor of President Jimmy Carter – John Carter, to whom Epaphroditus, according to his will, owed money to at the time of his death.

Epaphroditus married Elizabeth Medestard and they had one child, Elizabeth. Although Epaphroditus and Elizabeth had no male children, his name continued when his brother Rowland named his son after his uncle. I also found other lines who were related to the Lawsons – Epaphroditus Lawson Waring and Epaphroditus Lawson Fort.

John Lawson

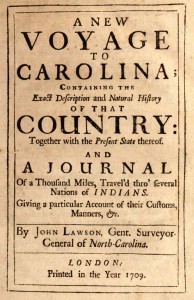

John Lawson was born in England on December 27, 1674 to parents John and Isabella Love Lawson. John Lawson was highly educated, likely schooled by the Anglicans and later at Gresham College near the family home in London. A friend later encouraged John to travel to America, suggesting that Carolina was the best country to visit. James Moore, a resident of Charles Town, who was in London at the time seeking the governship, granted John free passage on his ship. They arrived on August 15, 1700.JohnLawsonOn December 28, 1700 he set out on a 57-day expedition of the Carolina back country, accompanied by five other Englishmen and four Indians (three men and one woman). He possessed a keen eye for details and recorded a vast amount of information during his journey.

After traveling about 550 miles he came to the Pamlico region, and there he built a house and continued to explore. Later he helped found the town of Bath, established on March 8, 1705 by an act of the General Assembly, and becoming North Carolina’s first incorporated town. He was one of the town’s first commissioners and helped layout the town.

In 1709 John sailed back to England to oversee the publication of his extensive journal, A New Voyage to Carolina. In the book he included his journal notes, observations of the Native American population and drawings of animals and native plants.

John Lawson had also co-founded the town of New Bern with Christopher deGraffenreid. Arriving back from England on April 27, 1710, he brought with him three hundred Palatines who would settle the town of New Bern. Relations with the Indians were deteriorating, but John proposed a trip up the Neuse River in the summer of 1711 to see how far the river was navigable and whether it might lead to a shorter route to Virginia. John assured deGraffenreid that they would be safe.

John Lawson had also co-founded the town of New Bern with Christopher deGraffenreid. Arriving back from England on April 27, 1710, he brought with him three hundred Palatines who would settle the town of New Bern. Relations with the Indians were deteriorating, but John proposed a trip up the Neuse River in the summer of 1711 to see how far the river was navigable and whether it might lead to a shorter route to Virginia. John assured deGraffenreid that they would be safe.

When they came upon the Indian village of Catechna, they were captured. The Indians refused to release them, thinking that deGraffenreid was the Governor – an important capture. A late-night dispute arose as to whether the prisoners should be bound, but since a trial hadn’t been held as of yet, Lawson and deGraffenreid were free to move about the village. The next day, the king of the village brought food, described by deGraffenreid:

Toward noon the king himself brought us some food in a lousy fur cap. This was a kind of bread made of Indian corn, called dumplins, and cold boiled venison. I ate of this, with repugnance indeed, because I was very hungry.

When the trial was held, Lawson and deGraffenreid were questioned as to the purpose of their journey and why they had not informed the king of their intentions. Apparently the king was upset that his people had been mistreated, specifically by Surveyor-General Lawson, but Lawson defended himself, and it was decided that the two prisoners would be set free the next day. The next day, however, Lawson quarreled with the king and according to deGraffenreid, “this spoiled everything for us.”

When they attempted to leave, they were seized, a council of war was held and both were condemned to death. deGraffenreid “turned toward Mr. Lawson bitterly upbraiding him, saying that his lack of foresight was the cause of our ruin; that it was all over for us; that there was nothing better to do than to make peace with God and prepare ourselves betimes for death; which I did with the greatest devotion.” When they arrived at the war council, deGraffenreid approached an Indian who he described as dressing like a Christian and speaking English. He took the Indian aside and persuaded him to plead his case before the chiefs. Lawson and deGraffenreid were “bound side by side” to wait the judgment of the council.

Christopher deGraffenreid’s pleas for mercy were heard and his life would be spared, “but the poor Surveyor-General would be executed.” How he was executed, deGraffenreid was not certain. Some at the time said that Lawson was killed by having his throat cut with a razor from his bag, others said he was hanged or burned.

Alfred Lawson

Alfred William Lawson was born on March 24, 1869. During the early days of professional baseball, Alfred pitched around the league (Boston Beaneaters and Pittsburgh Alleghenys) but never made an impact. He managed in the minor leagues and founded his own league known as the Union Leagues of Professional Ball Clubs of America – it failed within one month.AlfredWLawsonAlfred’s next entrepreneurial endeavor was publishing an aviation magazine, “Fly”, to stimulate interest in aviation which was then in its infant stages. After moving to New York City, he renamed the magazine “Aircraft” and published until 1914. Alfred learned to fly in 1913 and eventually became an expert pilot. After advocating aviation for ten years, Alfred Lawson built his first airplane in 1917 and founded Lawson Aircraft Corporation.

Although he attempted to build a plane for military use (World War I), the plans fell apart. After the war, Alfred began a project with the goal of building the world’s first airliner. In 1920 an 18-passenger biplane airliner was demonstrated on a two thousand mile tour. The positive publicity allowed him to secure additional financing for his next project, a 26-passenger model called Midnight Liner. Unfortunately, on its maiden flight, the plane crashed and was never repaired. He later developed plans for a 100-passenger airline which was never built by his company. Alfred received the Winged America award later and cited by Scientific Age magazine as the “world’s leading passenger aeroplane builder.”

During the Depression years, he developed a theory of “direct credits” and wrote a book on the subject. He proposed that the government rather than banks should provide loans to individuals and businesses. Under his system, the people would have direct ownership of the money system.

During the Depression years, he developed a theory of “direct credits” and wrote a book on the subject. He proposed that the government rather than banks should provide loans to individuals and businesses. Under his system, the people would have direct ownership of the money system.

The most interesting thing I found about Alfred Lawson, however, was that he founded his own philosophy or religion – Lawsonomy, which combined physics, religion and economics. He was a vegetarian who developed a theory which combined diet, hygiene, rest and exercise that he believed could potentially allow a person to live to the age of two hundred – he called it “Lawsonpoise”.

He lectured and wrote books which attracted a following, so much so that he decided to found a school. The University of Lawsonomy was founded in Des Moines, Iowa in 1943, and the first group of seventy students grew vegetables (eating them raw) and flowers and studied Alfred Lawson’s writings.

The state of Iowa had designated the university as a non-profit organization, but in 1952 the IRS disagreed and revoked that status and demanded payment of back taxes. Lawson closed the school. He died in 1954. Alfred Lawson was definitely “one-of-a-kind”, a person with some “far-out” beliefs. One science writer later remarked that Lawson was “one of the nation’s unintentionally comic figures.”

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Ghost Town Wednesday: Nicodemus, Kansas

The American West has hundreds of abandoned ghost towns, but east of the Rockies some refer to towns that may still have a few residents as “quiet towns”. These towns have diminished over the years as residents moved away to bigger cities, post offices and schools closed and buildings fell into disrepair. Today’s ghost or “quiet” town has an interesting history with its founding in the post-Civil War Reconstruction years.

The American West has hundreds of abandoned ghost towns, but east of the Rockies some refer to towns that may still have a few residents as “quiet towns”. These towns have diminished over the years as residents moved away to bigger cities, post offices and schools closed and buildings fell into disrepair. Today’s ghost or “quiet” town has an interesting history with its founding in the post-Civil War Reconstruction years.

After the Civil War and Reconstruction, ex-slaves were eager to leave the South and strike out on their own in a new place. In 1877 an Indiana land developer, W.R. Hill, and a black minister, Reverend W.H. Smith, formed the Nicodemus Town Company. Smith became the town’s president and Hill the treasurer. How the name of the town originated is not exactly known, although some believe it was named after a slave who came to America and later purchased his freedom.

After the Civil War and Reconstruction, ex-slaves were eager to leave the South and strike out on their own in a new place. In 1877 an Indiana land developer, W.R. Hill, and a black minister, Reverend W.H. Smith, formed the Nicodemus Town Company. Smith became the town’s president and Hill the treasurer. How the name of the town originated is not exactly known, although some believe it was named after a slave who came to America and later purchased his freedom.

Did you enjoy this article snippet? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. This article has been updated significantly with new research and published in the July-August 2019 issue of the magazine. The magazine is on sale in the Digging History Magazine store and features these stories (100+ pages of stories, no ads):

- “Drought-Locusts-Earthquakes-B-Blizzards (Oh My!)” – Perhaps no state is possessive of a more appropriate motto than Kansas: Ad Astra per Aspera (“To the stars through difficulties”, or more loosely translated “a rough road leads to the stars”1). By the time the state adopted its motto in 1876, fifteen years post-statehood, it had experienced not only a brutal, bloody beginning (“Bloody Kansas”) but had endured (and continued to struggle with) extreme pestilence, preceded by severe drought and even an earthquake in April 1867. In the early days being Kansan was not for the faint of heart.

- “Home Sweet Soddie” – For years The Great Plains had been a vast expanse to be endured on the way to California and Oregon. Now the United States government was making 270 million acres available for settlement – practically free if, after five years, all criteria had been met. The criteria, referred to as “proving up” meant improvements must be made (and proof provided) by cultivating the land and building a home. For many their first home would be a dugout, a sod-covered hole in the ground.

- “Wholesale Murder at Newton” – It’s called “The Gunfight at Hyde Park” or the “Newton Massacre”. One newspaper headlined it as “Wholesale Murder at Newton”, another called it an “affray” and another a “riot”. Whatever, it was bloody, and one of the biggest gunfights in the history of the Wild West, more deadly than the legendary gunfight at the OK Corral.

- “Kansas Ghost Towns” – It might be more appropriate to call this Kansas ghost town, established by Ernest Valeton de Boissière in 1869, a “ghost commune” (Silkville). Nicodemus. There was something genuinely African in the very name. White folks would have called their place by one of the romantic names which stud the map of the United States, Smithville, Centreville, Jonesborough; but these colored people wanted something high-sounding and biblical, and so hit on Nicodemus.

- “The Land of Odds: Kwirky Kansas” – For some of us the mention of Kansas invokes memories of one of the classic films of our childhood, The Wizard of Oz. With a tongue-in-cheek reference this article highlights some of the state’s history and people in a series of vignettes – some serious, some not so serious (the real “oddballs”) in a light-hearted fashion. A rollicking fun article covering a range of Kansas “oddities” and “oddballs”, including one of the most dangerous quacks to have ever practiced medicine, Dr. John R. Brinkley.

- “Mining Kansas Genealogical Gold” – One of my favorite “adventures in research” is to discover obscure genealogical records or perhaps stumble across a set of records at Ancesty.com or Fold3 which turns out to be a gold mine of information. This article highlights some real gems available at Ancestry.

- “Chautauqua: The Poor Man’s Educational Opportunity” – During an era spanning the mid-1870s through the early twentieth century, Kansans, like many Americans across the country, anticipated the summer season known as Chautauqua, an event Theodore Roosevelt called “the most American thing in America”. By 1906 when Roosevelt made such an astute observation the movement had evolved into a non-sectarian gathering, where “all human faiths in God are respected. The brotherhood of man recreating and seeking the truth in the broad sunlight of love, social co-operation.”

- And more, including book reviews and tips for finding elusive genealogical records.

Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Tombstone Tuesday: John Baptiste Priquet (Saratoga, Wyoming)

John Baptiste Priquet, according to his death certificate, was born in Paris, France on April 18, 1843. Curiously, his gravestone (added later) says that he was born in 1846 and various family research sites indicate an April 14, 1846 date as well. His daughter’s signature is on the death certificate, thus I would assume she would have more intimate knowledge of his correct birth date… more on the death certificate later. Through the years of census records, his name was spelled, variously, Priquet, Priquette and Prickett.

John Baptiste Priquet, according to his death certificate, was born in Paris, France on April 18, 1843. Curiously, his gravestone (added later) says that he was born in 1846 and various family research sites indicate an April 14, 1846 date as well. His daughter’s signature is on the death certificate, thus I would assume she would have more intimate knowledge of his correct birth date… more on the death certificate later. Through the years of census records, his name was spelled, variously, Priquet, Priquette and Prickett.

According to census records, John immigrated to America in 1854 and at some point became a citizen. I found no immigration records, no census records for 1860 and 1870 and thus no record of his parents (likely due to misspelled names which hindered an accurate search). Various family histories indicate that John migrated to Idaho Springs, Colorado around the age of twenty-one. Whether he served in the Civil War is unknown. If the year was 1864, that was the year of the Sand Creek Massacre and as a previous Tombstone Tuesday article indicated, there was a mining boom in Colorado around that time.

The family of the woman he met and married, Adaline Melissa Schenck, migrated to Idaho Springs from Boone County, Illinois sometime after the 1860 census. At the time of the 1860 census, Melvin and Sarah Ann (Lanning) Schenck had four children, ranging in age from 3 to 15 – Adaline was 8 years old. Melvin and Sarah Ann were married on February 14, 1844 in Boone County, Illinois.

The family of the woman he met and married, Adaline Melissa Schenck, migrated to Idaho Springs from Boone County, Illinois sometime after the 1860 census. At the time of the 1860 census, Melvin and Sarah Ann (Lanning) Schenck had four children, ranging in age from 3 to 15 – Adaline was 8 years old. Melvin and Sarah Ann were married on February 14, 1844 in Boone County, Illinois.

It may not have been long after the 1860 census before the Schenck family headed to Colorado – one story said they traveled either with Mormons or as Mormon pioneers. Sarah Ann passed away on March 11, 1862, aged 35 years and 5 months. She was buried in what is now the foothill town of Evergreen, Colorado. The solitary grave is now on private property and surrounded by a small fence, left undisturbed all these years.

One genealogy researcher had thought that perhaps Melvin had died in 1860 (or perhaps soon after their arrival) at Pikes Peak. If that was the case, and Sarah died in 1862, their children were left as orphans. In 1870, Melvin and Sarah Ann’s son James was living in Golden City, Jefferson County, Colorado in the home of William Trotter, a hotel keeper. James’ occupation was listed as a 25 year-old hotel cook. According to one family tree, John and Adaline were married on April 4, 1867.

One genealogy researcher had thought that perhaps Melvin had died in 1860 (or perhaps soon after their arrival) at Pikes Peak. If that was the case, and Sarah died in 1862, their children were left as orphans. In 1870, Melvin and Sarah Ann’s son James was living in Golden City, Jefferson County, Colorado in the home of William Trotter, a hotel keeper. James’ occupation was listed as a 25 year-old hotel cook. According to one family tree, John and Adaline were married on April 4, 1867.

In 1866, John Priquet & Co. was assessed a tax of $3.60 for nine head of cattle. Unless John worked as a miner on the side he was a farmer or rancher.

In 1880 the census enumerated a family of six living in the Idaho District (Soda Creek) of Clear Creek County. John’s occupation was listed as “log hauler” and their four children at the time ranged in age from 1 to 11. The births of their children up until 1880 were as follows with six live births and two deaths:

Joseph Riley – b. August 18, 1869

Mary – b. February 6, 1871 (died February 12, 1871)

Sarah Ann – b. February 26, 1872

Wilbert Henry – b. April 6, 1875 (died May 4, 1875)

Leone Leota – b. May 4, 1876

William Lorenzo – b. July 7, 1878

The 1890 census records are unavailable but family historians believe that sometime in 1900 the family moved to Saratoga, Wyoming, after that year’s census. The 1900 census enumerated on June 15, 1900, lists the remainder of their children born after the 1880 census:

Etta Mable – b. August 23, 1880

Oscar Melvin – b. August 14, 1882

Claud Antoine – b. August 28, 1884

Carrie Felicia – b. September 24, 1886

Gertrude Valoria – b. May 24, 1889

The family was still living in Colorado in what then was called Idaho Springs. John was a wood hauler and sons William, Oscar and Antoine were “wood choppers” – presumably operating a family-run lumber business or sawmill.

It is not clear if John’s entire family migrated with him to Saratoga. Family history seems to indicate that all but perhaps Sarah Ann (who had married James H. McDonald in 1890) left with John and Adaline. In 1900, Sarah Ann was living in Cimarron, Oklahoma – one of her children was named “Idaho” and another “Arizona”. John and his sons cut wood at the Ferris-Haggerty Mine, one of the richest mines (copper) in Carbon County, Wyoming.

Joseph is said to have had an argument with his father around 1901, wherein he left Saratoga, moved to Montana and on to Oregon and never to be heard from again by his family. Claud Antoine passed away in 1903 (details unknown). According to the Saratoga Sun (April 8, 1907), William Priquet was instantly killed in a stagecoach accident at the Cow Creek Station of the Saratoga-Encampment Stage Line. The stage, stopped to water the horses, had three passengers. Two male passengers had stepped out of the coach and the female passenger remained inside. A sudden and sharp clap of thunder spooked the horses and:

Priquet caught the wheelers by the bridles and grabbed for the lines of the leaders, but stumbled into a depression in the ground. The leaders trampled on him and both wheels of the coach passed over him, crushing his skull, breaking his collar bone and his right leg below the knee. Death was instantaneous.

Deceased would have been 29 years of age the 7th of next July and was the eldest son of Mr. and Mrs. John Priquet of this place. He was a young man of excellent character and habits and was esteemed by all who knew him. His death fell with crushing force on his family and was a severe shock to the entire community.

By 1910, the remaining children had married and left home, except 24 year-old Carrie. John, Adaline and Carrie were still living together in Saratoga. John’s occupation was listed as “teamster”. Carrie was listed as “Hello Girl Telephone”. Carrie was said to have been crippled all her life (her nickname was “Tadpole”) and by the 1930 census she had married James Mauk (she still worked for the telephone company).

On May 7, 1913, Gertrude (who had married Fred Myers in approximately 1908 or 1909), died as a result of Bright’s disease and heart dropsy ten days after the birth of her son. She was laid to rest beside her brother William and her infant who had died two years before her death.

I found no 1920 census records for John and Adaline, although they were both still living in Saratoga. Their daughter Leone had married David Davis and was living in Littleton, Colorado when apparently her father (and perhaps her mother) were visiting since her name is on John’s death certificate. Find-A-Grave lists John’s year of death as 1925 (and for whatever reason, his birth is listed as being in 1846 in Gilpin County, Colorado – clearly incorrect information). John’s death certificate tells a tragic story, although I found no record of any compelling circumstances which lead to his death:

Death Certificate for John BapOn March 15, 1927, at age 83 years, 10 months and 27 days, John Baptiste Priquet died as a result of a revolver wound to the head – a suicide. His daughter, Leone, signed the death certificate as informant. He was buried in Saratoga Cemetery on March 17. After John’s death, Adaline’s health declined rapidly. Her last three years were spent as an invalid. In 1930 at the age of 79, she was living with James and Carrie Mauk in Saratoga. Adaline passed away the following year.

There were several gaps in John and Adaline’s history, but they most certainly experienced tragedies in their lives. Adaline had likely lost both parents after her family came to Colorado, perhaps leaving her and her siblings orphaned in a place of strangers. They experienced the death of both their very young and adult children and the estrangement of their oldest son Joseph. Whatever were the circumstances of John’s death, I could find no information – it even appeared in family histories to gloss over the fact that he committed suicide or that he died in Colorado rather than Wyoming. John and Adaline’s remaining family members, except for daughters Sarah and Leone, remained in Carbon County after the deaths of their parents.

I ran across a great story while researching this article. A blogger, known as “The Traveling Genealogist”, wrote an article in 2011 for Mother’s Day about Sarah Ann Schenck’s grave in Evergreen, Colorado. The blogger had some of the same questions I had – did her husband Melvin die at the same time but buried elsewhere or in an unmarked grave? Why did they come to Colorado from Illinois? In 2013, a commenter thanked him for finding his long-lost ancestor! I also hope my Tombstone Tuesday articles might help someone find some overlooked or missing piece of information – making all the time spent researching and writing the article more rewarding and well-worth the effort.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Surname Saturday: Pimple

This was a difficult surname to research – what with the Google results of “blemish control advice” or “family history of acne” interspersed and all. I came across the surname “Pimple” on a list of Revolutionary War soldiers last week when I was researching the “Pierson” surname. Along with Shadrack and Meshack Pierson, Private Paul Pimple from Pennsylvania received 200 acres of land for his war service. Private Pimple was injured while serving in the war and was pensioned in 1788 – 1835 pension records indicate he received an annual compensation of $60.

I found two other similar spellings of the name as well — “Pimpel” and “Pimpl”. I would assume that the ancestral homeland of Paul Pimple would be England or Wales. However, I do not know whether that was the original spelling or perhaps it was “Pimpl” and the “e” was added later. Information about the origin of the surname was hard to come by and even today it appears that the name is certainly not a common one.

I found two other similar spellings of the name as well — “Pimpel” and “Pimpl”. I would assume that the ancestral homeland of Paul Pimple would be England or Wales. However, I do not know whether that was the original spelling or perhaps it was “Pimpl” and the “e” was added later. Information about the origin of the surname was hard to come by and even today it appears that the name is certainly not a common one.

A search at Find-A-Grave of the entire United States yielded only 36 records (that is to say, those are the only ones recorded at Find-A-Grave as I’m sure there are many more but this was just a quick search for a point of reference). According to Ancestry.com the surname “Pimple” was most concentrated in Colorado in 1920. The search conducted at Find-A-Grave bore that out as there were far more entries for Colorado, specifically in Boulder and Logan County and all were buried in Catholic cemeteries. Wisconsin represented the next highest number of graves in the data base, followed by Kansas with two and one buried in Iowa, and again all buried in Catholic cemeteries.

A search at Find-A-Grave of the entire United States yielded only 36 records (that is to say, those are the only ones recorded at Find-A-Grave as I’m sure there are many more but this was just a quick search for a point of reference). According to Ancestry.com the surname “Pimple” was most concentrated in Colorado in 1920. The search conducted at Find-A-Grave bore that out as there were far more entries for Colorado, specifically in Boulder and Logan County and all were buried in Catholic cemeteries. Wisconsin represented the next highest number of graves in the data base, followed by Kansas with two and one buried in Iowa, and again all buried in Catholic cemeteries.

My research of records indicated that both the Pimpel and Pimpl surnames belonged to immigrants from Austria, Germany, Bavaria or the Czech Republic (Bohemia). It also appears that some of those immigrants changed their name to “Pimple” at some point. One immigrant, Wendelin Pimpl, appears to have added the “e” after he was naturalized in Minnesota – subsequent census and land records add the “e” (original “Pimpl” surname on his father’s gravestone, however) – more on Wendelin and his family later.

I ran across, surprisingly, names of people who were of Indian (the country India) origin with the surname “Pimple”. I checked a database of Indian surnames and found Pimple listed as being associated with the Yajurvedi sub-caste (whatever that means, I don’t know).

Historical information about this surname was hard to come by – even Ancestry.com didn’t offer much help. While there were several family trees, the majority had no records or sources attached. What I did find were lots of military records – through the years there were many who served in the military with the surnames Pimple, Pimpl and Pimpel. Here are a few:

Paul Pimple – Revolutionary War (Pennsylvania)

Jacob Pimple – Revolutionary War (Pennsylvania)

Paul P. Pimple – Civil War (Pennsylvania)

Joseph Pimple – World War I (Colorado)

Edward Earl Pimpel – World War I (Kentucky)

Lawrence Pimpl – World War I (Wisconsin)

Reverend Edward M. Pimple – World War II Prisoner of War

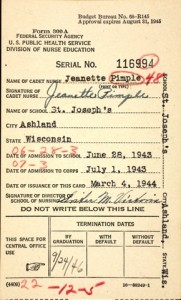

Jeanette Pimple – World War II Cadet Nursing Corps (Wisconsin)

I’m sure these were hard working individuals who answered the call to serve, and no doubt either immigrants or children and grandchildren of immigrants. Edward Earl (along with a relative named Henry) were employed as “varnishers” or “varnish sprayer” when called to serve in World War I. Reverend Edward M. Pimple was a Japanese prisoner of war, held in the Franciscan House (Shanghai), along with fifty-five other Catholic clergymen. Jeanette Pimple, the single daughter of John and Elizabeth (Yousten) Pimple of Almena, Wisconsin was twenty-two years old when she joined the Cadet Nursing Corps on July 1, 1943.

Jeanette was the granddaughter of Wendelin Pimple who immigrated to America from Bohemia (Austria) in 1855.

Wendelin Pimple

Wendelin Pimpl was born in Rojau, Bohemia, Austria on July 23, 1852 to parents Reimund and Kathrina (Wudinger) Pimpl. In 1855, Reimund brought his wife and three children to America. It appears that the family migrated to Wisconsin, and the first reliable census records I located were for 1870 in Calumet, Fond du Lac, Wisconsin. Their names were “butchered”, to put it mildly, but then again census takers notoriously weren’t the greatest spellers. I did find Wendelin in the 1860 census but not with his parents. Wendelin’s name was misspelled several different ways over the years:

Wendell (1860)

Windalen (1870)

Wendlin (1900-1920-1930)

Babdlin (1910)

Kenndell (1940)

Wendelin was naturalized as a United States citizen in Sterns County, Minnesota (date unknown). In the 1900 census, Wendelin’s wife Theresia was “Tracy”. Wendelin had married Theresia in 1884, so the 1900 census is the first one where most of their large family (twelve children) are enumerated. One family tree lists the children of Wendelin and Theresia as:

John Frederick – b. 1884

Elizabeth – b. 1885

Katrine – b. 1888

Christina – b. 1890

Theresa – b. 1891

Jacob – b. 1893

Frank – b. 1895

William – b. 1897

Emma – b. 1899

Ottilia (Della) – b. 1899 (twins)

Edith Marie – b. 1901

Edward Joseph – b. 1905

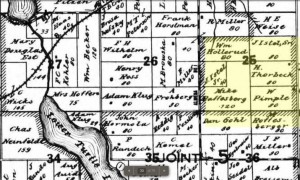

In 1900 Wendelin was a farmer living in Cedar, Nebraska. By 1910 the family had returned to Wisconsin, living in Almena, Barron County. This 1914 map shows a modest farm of 80 acres belonging to Wendelin:

In 1920 the family still lived in the same location; however, in 1924 Theresia passed away at the age of 61 on April 16, 1924. Their sons John, Jacob and Frank had all registered for the World War I draft, and they all registered for the World War II draft as well. Youngest son Edward enlisted in World War II on June 16, 1942. One other note of interest while perusing Edward’s records – the Wisconsin christening records list his race as “Colored (Black)” although his parents are listed as being born in Europe. As mentioned earlier, Wendelin’s granddaughter, Jeanette (daughter of John), enlisted in the Cadet Nursing Corps.

According to census records, it appears that Christina, Otillia, Emma and Edith never married. John married and had a large family and was employed as a merchant (with a sixth grade education), Jacob worked as a farmer (sixth grade education), Frank worked for Jacob in 1940 and was single (apparently never married), and Edward and Emma were living with their 87 year old father “Kenndell” in 1940.

Wendelin Pimple died on October 13, 1946 at the age of 94. Seven of his children are buried in the same cemetery (Sacred Heart) in Almena, Wisconsin. Unmarried daughter Christina is buried in Logan County, Colorado.

Death by Pimple

The Pimple surname is not common but it piqued my interest to see what I could find. I hope you enjoyed the story. As I said, it was hard to research the “Pimple” surname using Google – some subjects are more difficult than others no matter which search engine you use. I ran across these obituaries of young people who died, well, by pimple:

Died of Blood Poisoning – Daughter of Mr. and Mrs. Joseph Washburn of DeKalb Poked Pimple which Resulted in Death

Mr. and Mrs. W. S. Washburn left this morning to attend the funeral of Mr. Washburn’s niece, the 21-year-old daughter of Mr. and Mrs. Joseph Washburn of DeKalb, who died Monday as a result of blood poisoning. About a week ago Miss Washburn had a slight pimple on her forehead which she picked with her finger and brought the blood. Poisoning developed later and which resulted in her death Monday. (Gourvenor Press – August 14, 1907)

Ruth Edna Arrendell Casey – died Sep 10 1928; cause of death – infection from pimple on nose

Newspaper Unknown – September 15, 1924

Forest C., son of Mr. And Mrs. L. C. Cordell of near Cantrall, died at the St. John’s hospital in Springfield, Monday afternoon, September 15, 1924, at 12:45 o’clock, aged 13 years, 9 months and 13 days.

Death was caused from an infection of a pimple on his lip. He had been ill only about five days. The family have the sympathy of the entire community in their sad bereavement. Death has taken from them the only son just as he was entering upon the age of usefulness and at a time when his interest in his school work was the pride of his parents.

Minnie Hummel was born on July 10, 1877 in Schuylkill County, Pennsylvania. She died on February 22, 1898. Her death was due to ‘picking a pimple’ and she developed blood poisoning.

Of course, while I meant to end this article with a bit of tongue-in-cheek, it was quite unfortunate that these individuals lived in a time before effective antibiotics and treatments had been developed. Just another reminder of what our ancestors endured and what history can teach us.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

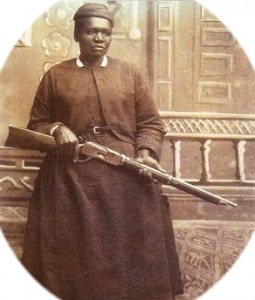

Feisty Females: Stagecoach Mary

Mary Fields, a.k.a. “Stagecoach Mary” was born in Tennessee as a slave. Nothing much is known about her early life, except that she was orphaned and, unlike other slave children of that day, she learned to read and write.

Mary Fields, a.k.a. “Stagecoach Mary” was born in Tennessee as a slave. Nothing much is known about her early life, except that she was orphaned and, unlike other slave children of that day, she learned to read and write.

One important person in her life would be Dolly Dunne, born as the fifth child of John and Ellen Dunne, Irish immigrants living in Akron, Ohio. John Dunne, according to Ursuline Sisters of Great Falls, went to California in 1856 to join the gold rush. However, Dolly and her older sister were left behind in Ohio at an Ursuline (order of nuns) boarding school. Dolly formally entered the convent in 1861 and took her vows as an Ursuline nun on August 23, 1864 and was elevated to Mother Superior in 1872.

In my research, I found that the story of how Mary Fields became linked to the Dunne family varies. Some have Mary being born near the time of Dolly’s birth and the two growing up together. Dolly was born on July 2, 1846 in Akron, Ohio, and according to most sources, Mary was born in approximately 1832 – so that doesn’t seem too credible. Some say Mary worked for Dolly’s brother, Judge Edmund Dunne, and that’s how they were acquainted. It does, at least, appear that sometime during the 1870’s Mary was in Ohio and perhaps worked for Mother Mary Amadeus, a.k.a. Dolly Dunne.

In my research, I found that the story of how Mary Fields became linked to the Dunne family varies. Some have Mary being born near the time of Dolly’s birth and the two growing up together. Dolly was born on July 2, 1846 in Akron, Ohio, and according to most sources, Mary was born in approximately 1832 – so that doesn’t seem too credible. Some say Mary worked for Dolly’s brother, Judge Edmund Dunne, and that’s how they were acquainted. It does, at least, appear that sometime during the 1870’s Mary was in Ohio and perhaps worked for Mother Mary Amadeus, a.k.a. Dolly Dunne.

In 1881 Mother Amadeus departed for Montana Territory to establish schools for Indian children. She established schools and a convent, and in 1884 a girls mission school was opened near Cascade, Montana. She became seriously ill in 1885 with pneumonia and was nursed back to health by Mary Fields, who traveled from Ohio to Montana to assist her friend.

Mary Fields, by all accounts, cut an imposing figure. She was at least six feet tall and weighed about two hundred pounds. Mary also had a penchant for smoking cigars, having a pistol strapped under her apron and having a jug of whiskey nearby, according to Extraordinary Women of the American West by Judy Alter. Actor Gary Cooper and his family lived in Helena, Montana and he remembered seeing Mary when they visited Cascade when he was about nine years old.

The school buildings were in a state of disrepair, so after nursing her friend back to health Mary decided to stay and help – hauling freight, doing laundry, gardening and even supervising the repair of the buildings as a forewoman. According to an article written by Gary Cooper (as the story was told to Marc Crawford) in the October 1959 issue of Ebony Magazine, Mary celebrated her birthday twice each year because she was not certain when exactly she was born. Cooper verified her thirst for hard liquor – citing a historical fact that one of the early mayors of Cascade, D.W. Monroe, made an exception and gave Mary the special privilege of being allowed to enter the saloons and drink with the men. Charlie Russell, renowned western artist, memorialized her with a pen and ink drawing that was displayed in the Cascade Bank.

The school buildings were in a state of disrepair, so after nursing her friend back to health Mary decided to stay and help – hauling freight, doing laundry, gardening and even supervising the repair of the buildings as a forewoman. According to an article written by Gary Cooper (as the story was told to Marc Crawford) in the October 1959 issue of Ebony Magazine, Mary celebrated her birthday twice each year because she was not certain when exactly she was born. Cooper verified her thirst for hard liquor – citing a historical fact that one of the early mayors of Cascade, D.W. Monroe, made an exception and gave Mary the special privilege of being allowed to enter the saloons and drink with the men. Charlie Russell, renowned western artist, memorialized her with a pen and ink drawing that was displayed in the Cascade Bank.

Mary Fields, as you can imagine, was quite a character. According to the Ebony article, Mary not only worked to repair the school but she also handled the job of hauling supplies, often driving through the night in storms and certainly fraught with danger. On one trip a blizzard had overtaken her and when she was unable to see the road she had to stop, but throughout the night she walked back and forth to keep from freezing to death.

Mary was known to have a terrible temper, and mixed it up with the men who worked for her (who, no doubt, resented the fact that a woman – a black one at that – was their boss). At one point the situation escalated to an incident involving gun play with one of her subordinates. Complaints were brought to the bishop, who subsequently ordered the nuns to send her away. Mother Amadeus came to her rescue when she helped Mary open a restaurant, but Mary was too soft-hearted. Sheep herders in the winter were fed even if they couldn’t pay, promising to pay her by summer – which they never did. Mary’s restaurant business failed.

Undaunted, Mother Amadeus contacted government officials (perhaps without the bishop’s knowledge) and asked to have Mary assigned a mail route. Probably to the bishop’s dismay when he found out, Mary was assigned the route from Cascade to the school! According to Cooper’s article, every morning she “made her triumphant entry into the mission seated on top of the mail coach dressed in a man’s hat and coat and smoking a huge cigar.”

Mary executed her duties faithfully for eight years and she had rightfully earned her nickname “Stagecoach Mary”. Again, according to Cooper’s article, one day Mary was thrown from her coach and was injured. When she arrived at the mission the sisters encouraged her to return to the faith that she had, for the most part, abandoned when expelled from the mission. So, Mary confessed her sins and returned the next morning wearing a dress with a white veil that the sisters had made for her (usually she wore men’s clothes). High Mass was celebrated – Mary had returned to God!

Mother Amadeus was assigned to a mission in Alaska in 1903, and after her injury Mary no longer delivered the mail. She began doing laundry even though by then she was around seventy years old. Cooper shared one more humorous anecdote – Mary was sitting one day in the saloon when a customer passed by who owed her two dollars. She followed the gentleman outside, grabbed him by the shirt collar, knocked him down and demanded payment. When she returned to the saloon, she remarked, “His laundry bill is paid.”

In 1912 her laundry was destroyed by fire and the townspeople helped her rebuild her home, providing lumber and labor. In 1910 a proprietor of the New Cascade Hotel had arranged that Mary receive all her meals for free at the hotel. She also served as mascot for the local baseball team. Mary never married and never really smoothed out her “rough edges”, but when she died the town mourned her – she was one of a kind for sure, and a feisty one at that!

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Off the Map: Ghost Towns of the Mother Road – Chambless, California

In the early 1920’s, James Albert Chambless of Arkansas settled in the Amboy area, near the intersection of Cadiz road and the National Trails Road. The family built a store in the late 1920’s after the National Trails Road was renamed Route 66. In 1932, a gas station, motel and another store were added to Chambless Camp (as it was known). In 1939 a Post Office was opened — cabins and a café were also built.

In the early 1920’s, James Albert Chambless of Arkansas settled in the Amboy area, near the intersection of Cadiz road and the National Trails Road. The family built a store in the late 1920’s after the National Trails Road was renamed Route 66. In 1932, a gas station, motel and another store were added to Chambless Camp (as it was known). In 1939 a Post Office was opened — cabins and a café were also built.

In the late 1930’s, James married Fannie Gould, who is said to have turned the camp into a desert oasis, with a rose garden and fish pond. The auto repair shops kept busy even in the remote location. Travelers needing repairs had cafes to eat at and cabins or motels to sleep in while they waited – with business so brisk, it could sometimes be days before repairs were completed.

In the late 1930’s, James married Fannie Gould, who is said to have turned the camp into a desert oasis, with a rose garden and fish pond. The auto repair shops kept busy even in the remote location. Travelers needing repairs had cafes to eat at and cabins or motels to sleep in while they waited – with business so brisk, it could sometimes be days before repairs were completed.

The building where Fannie ran a gas station, grocery and café had a large covered porch area – something that was a welcome relief in the scorching desert heat. Fannie made lemonade for the soldiers who came to the area during World War II for desert training. One source said that some two million soldiers passed through the area surrounding Chambless during the war.

About a mile and a half west of Chambless the Roadrunner’s Retreat (café and gas station) was a well-known landmark, but today the property lies in ruins. Of course, business for Chambless Camp boomed (as it did for other towns along Route 66) during the peak years, but eventually the townspeople left and buildings fell into disrepair (the Camp porch was blown away at some point).

In 1990, Gus Lizalde purchased Chambless with the intent to restore it to its former glory days. He was able to open the gas station in the late 1990’s, but forced to close when the underground storage tanks became unstable. Gus seems determined (or was at least in late 2009) to keep working to restore Chambless. His last blog post here was written on December 30, 2009 and he is listed on LinkedIn as the CEO at Chambless California Water Services, Inc.

For an article in the Riverside Press-Enterprise in November 2009 he described his vision:

“It’s going to be a full-blown restoration to the way it was built,” Lizalde said. “I want to bring back that nostalgia. The renewed Chambless would feature “totem” gasoline pumps with meters that look like clock faces. Lizalde said he wants to track down original pump bodies and retrofit them with modern gas-delivery and metering systems.

The main building would have a 1950s-style diner, a tavern and a souvenir/convenience store. He intends to fix up the nine concrete cottages behind the main building and build a swimming pool in the shield shape of the Route 66 road sign. For the trailer park area, Lizalde envisions hauling in about 50 vintage Airstream trailers, refurbishing them and renting them out.

Why Airstreams? “They are so cool,” he answered.

Gus also hoped to replace the Roadrunner Café sign with one of his own, according to The Route 66 Cookbook: Comfort Food from the Mother Road. This book was published in 2003 and at the time Gus was said to have employed a cook and served “the best Mexican food you’ll find on the road.” In 2009 he also sent a letter to Senator Dianne Feinstein touting a solar power project (apparently Senator Feinstein had opposed efforts). I love nostalgia, and if Gus is continuing to pursue his dream of restoring Chambless, I wish him great success!

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

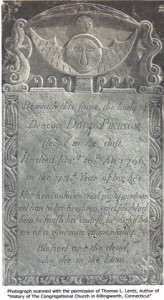

Tombstone Tuesday: Shadrack, Meshack and Abednego Pierson

In 1754 three sons were born to Charles and Sally (Weathers) Pierson in Culpeper County, Virginia. The boys were named, perhaps in order of birth, Shadrack, Meshack and Abednego. Charles and Sally were the parents of at least one other child, Charles. My internet research indicates that Charles was a wealthy man at one point, but when his warehouses were raided by Revolutionary soldiers he was left penniless. You see, it is reported that Charles was a Loyalist, and while not finding anything but unsourced anecdotal information, it is clear that he left (probably fled) Virginia at some point, first to South Carolina and then to Wilkes County, Georgia where he lived until his death in 1799.

In 1754 three sons were born to Charles and Sally (Weathers) Pierson in Culpeper County, Virginia. The boys were named, perhaps in order of birth, Shadrack, Meshack and Abednego. Charles and Sally were the parents of at least one other child, Charles. My internet research indicates that Charles was a wealthy man at one point, but when his warehouses were raided by Revolutionary soldiers he was left penniless. You see, it is reported that Charles was a Loyalist, and while not finding anything but unsourced anecdotal information, it is clear that he left (probably fled) Virginia at some point, first to South Carolina and then to Wilkes County, Georgia where he lived until his death in 1799.

Three of his children, sons Shadrack, Meshack and Charles, apparently had a different viewpoint than their father’s – they joined the Revolutionaries (more about Abednego later).

This article is no longer available for free at this site. It was re-written and enhanced, complete with footnotes and sources and has been published in the July 2018 issue of Digging History Magazine. Should you prefer to purchase the article only, contact me for more information.

This article is no longer available for free at this site. It was re-written and enhanced, complete with footnotes and sources and has been published in the July 2018 issue of Digging History Magazine. Should you prefer to purchase the article only, contact me for more information.

I invite you to check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Surname Saturday: Pierson

The Pierson surname originally meant “son of Piers” – possibly from French “Pierre” or “Peter”. The Greek origin would be “Petros” or rock (in the Bible Simon was given the name “Peter” by Jesus). The surname is of early medieval English origin with various spellings such as Pierson, Peirson, Pearson and even Parsons. According to Lillie B. Pierson’s Pierson Genealogical Records (1878), “Pierson is considered to be the most correct manner of spelling the name, as deduced through the French Pierre.”

Reverend Abraham Pierson

One of the first Piersons to immigrate to America in 1639 was Reverend Abraham Pierson, who had been ordained in the Episcopal Church in England. When Abraham arrived in America he was ordained in Boston as a Congregational minister. He lived in Boston before departing for Southampton, Long Island where he remained until 1647. He had first attempted to settle on the west end of Long Island, but the Dutch already controlled that end, so he went to the east end and founded Southampton.

The church that Abraham founded was Congregational but later became Presbyterian. Abraham was religiously staunch in his beliefs, so much so he believed everything in Southampton, even civic affairs, must be handled through the church. His congregation was divided on that sentiment and he left in 1647 to found the town of Branford, Connecticut. For almost twenty years he labored in Branford, ministering to the local Indians and learning their language. His work was lauded by the likes of prominent Puritan minister Cotton Mather – “wherever he came he shone.”

Abraham left Branford in 1666, taking most of his congregation with him to the banks of the Passaic River to found the town of Newark (perhaps named in honor of the town in England where he was ordained). The church they founded was the first in Newark and for twelve years Abraham faithfully led his flock until he died in 1678. His son, Abraham, was also a minister and the first rector and one of the founders of the Collegiate School (later Yale University).

One of Abraham’s (Senior) great-grandchildren, whose father was also named Abraham, was named “Dodo” (b. 1723) and he was a deacon in the church. Family tradition says that a maiden aunt objected to the name “Dodo” being placed upon the child. She was overruled and later Deacon Dodo Pierson became known as a patriot. One account states that Dodo left his home in Killingworth, Connecticut and went to Rye in Westchester County, New York while the army was encamped there. It is not known his reason for going there, whether as a volunteer or to visit his son. Nevertheless, he took his musket and served as a sentinel even though he was advanced in age.

Henry Pierson

Henry Pierson had also settled in Southampton with Abraham and it is probable that they were either brothers or some other close relation. However, Henry remained in Southampton when Abraham moved to Connecticut, raising a large family, with some of them migrating to New Jersey later.

One of Henry’s grandsons, Azel Pierson, was born in Cumberland County, New Jersey and later became a doctor. Azel was well-educated and besides the medical profession he excelled in mathematics. He visited his patients on horseback and was especially fond of deer and fox hunts. He was known to be a bit uncouth in his mannerisms and speech, but still remained a well-respected physician and citizen who eventually became involved in politics, serving as county clerk while still practicing medicine. In 1813, Azel visited a patient who had typhus fever which he contracted and died from. The patient was a Christian, but Azel had made no profession of faith. One minister remarked, “what a happy circumstance it would have been if the patient and his doctor could have exchanged places… but our ways are not the ways of God.”

One of Henry’s grandsons, Azel Pierson, was born in Cumberland County, New Jersey and later became a doctor. Azel was well-educated and besides the medical profession he excelled in mathematics. He visited his patients on horseback and was especially fond of deer and fox hunts. He was known to be a bit uncouth in his mannerisms and speech, but still remained a well-respected physician and citizen who eventually became involved in politics, serving as county clerk while still practicing medicine. In 1813, Azel visited a patient who had typhus fever which he contracted and died from. The patient was a Christian, but Azel had made no profession of faith. One minister remarked, “what a happy circumstance it would have been if the patient and his doctor could have exchanged places… but our ways are not the ways of God.”

Thomas Pierson

Thomas Pierson’s name was first recorded in the town of Branford, Connecticut when he married Maria Harrison on November 27, 1662. It is possible that Thomas was also Abraham’s brother (or possibly a nephew). Thomas was a weaver and when Abraham left Branford for Newark, Thomas was one of the signers of the heads of families in Branford to remove to Newark. Thomas became involved in civic matters in Newark, first as a townsman (1677), then a constable (1679) and grand juryman (1680). As the Pierson Genealogical Records notes, “[T]hus while Abraham led the band of emigrants in their spiritual interest, Thomas was active in discharging official duties.” He was a witness for Abraham’s will in 1668.

Many of Thomas’ descendants migrated to Orange, Essex County, New Jersey. Matthias Pierson was born in 1734 in Orange where he lived his entire life, marrying Phebe Nutman and having a large family of eight children. Matthias became a doctor who served his town of Orange and the surrounding area, traveling on horseback, and he was known to be a man of great integrity. He was concerned about the affairs of his town and was especially mindful of the need for proper education. Matthias was a patriot who rallied his fellow citizens. At one point, British soldiers entered Orange and took possession of his house (while the family had fled to safety in the mountains). The soldiers made use of his home, but left his closet of medicine and a fresh loaf of bread untouched. Matthias’ son, Isaac, was also a doctor who was especially skilled in the treatment of fevers.

One branch of the Pierson-Peirson-Pearson-Person line emigrated to Philadelphia in 1699 as Quakers. Samuel Peirson and his family migrated to North Carolina and when the French and Indian War ended in 1763 he and all but two children are said to have been murdered by the Indians. His son, Samuel, was born in Philadelphia in 1731 and became a captain who sailed to China. Upon his return he was a businessman in Boston, who witnessed some of the first volatile events of the Revolution. The Boston Massacre was very near his home and one of the wounded fell on his doorstep.

There were other branches and lines of Piersons scattered throughout the colonies, and over time the Piersons made their way across America. For instance, the Quaker line that went to North Carolina from Philadelphia migrated to Randolph County, Indiana because of the slavery issue. Pierson occupations included farmers, hatters, tanners, weavers, doctors, missionaries, ministers and more. One Pierson family I came across in my research lived in Culpeper County, Virginia and will be the subject of next week’s Tombstone Tuesday article – triplets named Shadrach, Meshach and Abednego Pierson.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Tombstone Tuesday: Absalom Baker Scattergood

Absalom Baker Scattergood was born on July 11, 1822 in Dolington, Bucks County, Pennsylvania. I was unable to definitely determine who his parents were, although one source lists his parents as John Head and Catherine (King) Scattergood. I believe, based on the history of the area encompassing Bucks County, Pennsylvania and across the river to Burlington, New Jersey, that Absalom’s family would have been Quakers more than likely. According to the records of the First United Methodist Church of Mount Holly, New Jersey, Absalom married Rachel King on August 12, 1843, so at some point Absalom had left the Society of Friends and joined the Methodist Church. According to church records, he was a member of the First United Methodist Church in 1840.

Absalom Baker Scattergood was born on July 11, 1822 in Dolington, Bucks County, Pennsylvania. I was unable to definitely determine who his parents were, although one source lists his parents as John Head and Catherine (King) Scattergood. I believe, based on the history of the area encompassing Bucks County, Pennsylvania and across the river to Burlington, New Jersey, that Absalom’s family would have been Quakers more than likely. According to the records of the First United Methodist Church of Mount Holly, New Jersey, Absalom married Rachel King on August 12, 1843, so at some point Absalom had left the Society of Friends and joined the Methodist Church. According to church records, he was a member of the First United Methodist Church in 1840.

This article is no longer available at this site. However, it will be enhanced and published later in a future issue of Digging History Magazine, our new monthly digital publication available by individual purchase or subscription. To see what the magazine is all about you can preview issues at our YouTube Channel. Subscriptions are affordable, safe and easy to purchase and the best deal for getting your “history fix” every month.

This article is no longer available at this site. However, it will be enhanced and published later in a future issue of Digging History Magazine, our new monthly digital publication available by individual purchase or subscription. To see what the magazine is all about you can preview issues at our YouTube Channel. Subscriptions are affordable, safe and easy to purchase and the best deal for getting your “history fix” every month.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Surname Saturday: Scattergood

There is debate regarding the meaning of the surname “Scattergood”. On the one hand, some think it perhaps refers to someone who is wasteful and careless with their money, and on the other hand, some think it actually refers to a philanthropist who gives his money to help others. The surname was first seen in thirteenth century England: Wimcot Schatregod and Thomas Scatergude appeared on the census rolls in 1273. In 1703 Henry Edwards married Elizabeth Scattergood in London and Joshua Scattergood married Elizabeth Wilson in Philadelphia in 1742.

The Scattergood name is “scattered” around America, with the largest concentration in Pennsylvania, where according to Ancestry.com there are 27-51 families with that surname. I believe that many Scattergoods were Quakers – one prominent Scattergood who was a Quaker minister is discussed in this article. There’s also an interesting story about the Scattergood Hostel, located in West Branch, Iowa, where many European refugees fleeing Hitler’s tyranny were sheltered – a sort of Schindler’s List on the prairie.

Thomas Scattergood

Thomas Scattergood was born on January 23, 1748 in Burlington, New Jersey to parents Joseph and Rebecca (Watson) Scattergood. Thomas’ life was marked by tragedy – his father died when he was only six years old and his first wife Elizabeth (Bacon) died in 1780 after eight years of marriage. Thomas married Sarah Hoskins in 1783.

He had been trained as a tanner, but was drawn to the ministry through his local Friends congregation. He was prone to melancholy, perhaps as a result of the tragedies he experienced in his life – he was sometimes referred to as a “mournful prophet”. However, Thomas was dedicated to Quaker ministry and set out in 1794 to England to further his spiritual education. While there he preached and visited local congregations, prisons, schools and orphanages, and his sympathy for those who suffered was palpable.

He had been trained as a tanner, but was drawn to the ministry through his local Friends congregation. He was prone to melancholy, perhaps as a result of the tragedies he experienced in his life – he was sometimes referred to as a “mournful prophet”. However, Thomas was dedicated to Quaker ministry and set out in 1794 to England to further his spiritual education. While there he preached and visited local congregations, prisons, schools and orphanages, and his sympathy for those who suffered was palpable.

In that era of history, people who suffered from mental illness were not treated well – even contemptibly. Some considered them demon-possessed and perhaps even deserving of death – certainly they needed to be put away from polite society. The Quakers have a different view of the mentally ill – they believe every human being has an “inner light” of divine origin.

In 1791 a young Quaker woman, Hannah Mills, developed acute mental illness and was admitted to the York Asylum. Her family didn’t leave near York so they asked their Quaker friends to visit her; however, when the friends tried to visit they were turned away, told that Hannah was in no condition to receive visitors. She died not long after that and her plight became a cause for the York Society of Friends.

In 1795 the York meeting had organized their own facility to treat the mentally ill – York Retreat – where they were determined that all patients would be treated morally and with dignity. The facility experienced positive results with their approach, and before Thomas Scattergood returned to Philadelphia, he dined with the founder of York Retreat, William Tuke. The next day Thomas visited the facility and spoke with patients, noting in his diary, “We sat in quiet, and I had vented a few tears, and was engaged in supplication.”

In 1795 the York meeting had organized their own facility to treat the mentally ill – York Retreat – where they were determined that all patients would be treated morally and with dignity. The facility experienced positive results with their approach, and before Thomas Scattergood returned to Philadelphia, he dined with the founder of York Retreat, William Tuke. The next day Thomas visited the facility and spoke with patients, noting in his diary, “We sat in quiet, and I had vented a few tears, and was engaged in supplication.”

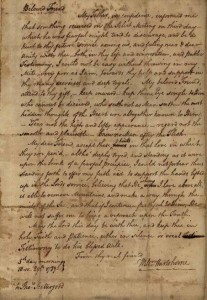

When he returned home Thomas began working with a new school in Westtown, but he was always encountering people with either mental illness or other maladies such as alcoholism. He would then get side-tracked from his other work and spend hours counseling and praying with those individuals. Thomas began speaking with his Quaker friends about the plight of mental illness, and at the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting in 1811 he proposed that they create a means to take care of the mentally ill.

The Friends Hospital was founded in 1817; however, Thomas had contracted typhus fever and died in 1814. He was survived by his wife, Sarah, and his children Joseph and Rebecca. From the Haverford College Collection of Scattergood Family Papers (1681-1909), two letters to Thomas Scattergood – one encouraging him in his ministry and the other from someone what had been encouraged by Thomas’ ministry:

Scattergood Hostel

Scattergood Friends School opened in 1890 in West Branch, Iowa. The members of the Hickory Grove Quarterly Meeting (Quaker) had arrived in Iowa from Ohio and later desired a school where their young people could receive a “guarded education”, away from “early knowledge of, or contact with, the evils of the world.” The idea was conceived in 1870 but it took twenty years of planning and work before the school opened in 1890. An early goal of the school:

…the aim of the school is to give a substantial English education, suited to fit the average person for the ordinary duties of life, and at the same time prepare students for higher institutions of learning, yet it is still its distinctive purpose to shield the young from hurtful temptations and distracting tendencies during the character-forming period.

The first class of twenty-five Quaker students were charged a tuition fee of $100 per year. In 1917 the Hickory Grove group left the parent Ohio group and joined the Iowa Yearly Meeting and thus the ownership was transferred to the Iowa Yearly Meeting. According to the school’s web site, that move prompted a loosening of the dress code – girls were no longer required to wear bonnets and boys no longer had to turn in coat collars.

Like everyone else in the country, the Depression of 1929 was devastating to the school and in 1931 the decision was made to close, hoping it would be a short-lived closure. The school, however, remained closed until in 1938 the American Friends Service Committee (AFSC) suggested that perhaps the school could be used to shelter European refugees fleeing the Nazi regime. The plight of the refugees had struck a sympathetic chord and now the Friends were determined to offer help.

Volunteers flooded to the town of West Branch to help renovate the property and assist in any way possible. Local officials, the postmaster, clergy and Jewish organizations all offered encouragement and support. Space was allotted for a garden and farm animals since one of the goals was to make the project self-sustaining.

In July of 1939, “guests” (as opposed to calling them “refugees”) began arriving. The goal of the AFSC was that guests “could go for a few weeks or months to recover from their effects of their recent experiences, regain their confidence, improve their English, learn to drive a car, and, if needed be, start retaining themselves for some new line of work before seeking a permanent place in American society.” Quakers had an aversion to organized levels of management and sought to run things less rigidly than might be expected, and perhaps that helped those who came feel more human and more hopeful about their futures.

During the four years the hostel operated, 186 refugees found a welcoming place. Residents were expected to pitch in and help with daily chores (gardening, washing dishes, folding laundry, etc.) – something that was foreign to many of the residents who formerly were well-off professionals who had employed household staff. Some of the people were seen trying to hoard food, and some had family members who had perished in Hitler’s gas chambers, so they were always anxious to hear news from “home”.

The hostel was a place to recover from the traumas experienced in war-torn Europe. The residents were grateful for the chance to, in many cases, begin their lives over. There were many notes and letters of thanks – one man wrote that the hostel was a “place of peace in a world of war, a haven amidst a world of hatred.”

The hostel closed in March of 1943 and in 1944 the Scattergood School re-opened. The school is still operating today, although the tuition has risen considerably to $26,700 per year for boarding students. If you’d like to read more about the history of the school and the hostel, check out these links:

Scattergood School

Rescuers of Jews

Jim Scattergood of Irving, Texas remarked on a message board, “Scattergood clan it’s always good at the end”. Be sure to stop by next week for a Tombstone Tuesday article on Sgt. Absalom B. Scattergood.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!