Motoring History: Henry Ford – Maker of Men (Part Two)

Henry Ford and his car company hit a home run with the Model T – and he knew it (see Part One of this series). On January 1, 1910 he opened his new factory in Highland Park with the intention of producing one thousand Model T’s a day. His whole business model centered around making an inexpensive, affordable product for the masses. Machine parts could be made quickly but assembling cars was another story. Again, Henry Ford began to tinker.

Henry Ford and his car company hit a home run with the Model T – and he knew it (see Part One of this series). On January 1, 1910 he opened his new factory in Highland Park with the intention of producing one thousand Model T’s a day. His whole business model centered around making an inexpensive, affordable product for the masses. Machine parts could be made quickly but assembling cars was another story. Again, Henry Ford began to tinker.

One member of his team proposed an idea based on a conveyor system used in meat-packing plants. As the animal carcass moved along the conveyor throughout the plant, meat cutters cut pieces from the animal. They thought a sort of reverse conveyor process would work – put the machine on a conveyor and move it past people to place things on it. To test the theory his team tried it out in the flywheel magneto department. Instead of one person building one coil at a time, individual tasks were broken down – each person along the conveyor had a specific task to perform. Previously it had taken twenty minutes to assemble and with the new system it would drop to just over thirteen minutes.

One member of his team proposed an idea based on a conveyor system used in meat-packing plants. As the animal carcass moved along the conveyor throughout the plant, meat cutters cut pieces from the animal. They thought a sort of reverse conveyor process would work – put the machine on a conveyor and move it past people to place things on it. To test the theory his team tried it out in the flywheel magneto department. Instead of one person building one coil at a time, individual tasks were broken down – each person along the conveyor had a specific task to perform. Previously it had taken twenty minutes to assemble and with the new system it would drop to just over thirteen minutes.

This article is no longer available at this site. However, it will be enhanced and published later in a future issue of Digging History Magazine, our new monthly digital publication available by individual purchase or subscription. To see what the magazine is all about you can preview issues at our YouTube Channel. Subscriptions are affordable, safe and easy to purchase and the best deal for getting your “history fix” every month.

This article is no longer available at this site. However, it will be enhanced and published later in a future issue of Digging History Magazine, our new monthly digital publication available by individual purchase or subscription. To see what the magazine is all about you can preview issues at our YouTube Channel. Subscriptions are affordable, safe and easy to purchase and the best deal for getting your “history fix” every month.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Surname Saturday: Blood

Blood

This surname was possibly derived from the Welsh name Lloyd. The original form of the surname was “Ab-Lloyd” with the prefix “ab” meaning “son of”. From “Ab-Lloyd” the name eventually evolved to “Blud” and then “Blood”.

Some sources suggest two additional theories for this surname’s origination:

- The name is an affectionate term for a blood relative.

- The surname may have derived from an occupational name for a physician, i.e., one who lets blood (“bloden” from Middle English)

The first recorded spelling of the surname was in 1256 during King Henry III’s reign for “William Blod”. Other spelling variations of this surname include “Blud”, “Bludd”, “Bloode” and “Blood”.

While it is believed that the surname is more likely of Welsh origin, some members of the Blood family moved to Ireland in the 1590’s. One member of this family branch, Thomas Blood, made a name for himself when he attempted to steal the Crown Jewels from the Tower of London in 1671.

Thomas Blood

Thomas Blood had joined the Parliamentarians (or “Roundheads”) during the Irish rebellion which coincided with the English Civil War (1642-1651). Their foes were the Royalists (or “Cavaliers”) and their conflicts arose over disagreements relating to governance, whether Parliamentary or directly through the monarchy. The Parliamentarians were victorious and thereafter precedent was set for the monarchy to govern only with Parliament’s consent.

Members of the Parliamentary Army were rewarded with large estates. However, when the monarchy was restored (with governing limits), Thomas lost his land. Revenge was in order, so he organized a band of men in 1663 to overthrow Dublin Castle and capture a Royalist and supporter of King Charles II, James Butler, the Duke of Ormond. Their plans were thwarted and exposed, however. Thomas was able to escape to Holland, disguising himself both as a Quaker and a priest, but his accomplices were executed. Obviously, there was a price on his head so he remained in Holland for a time.

He joined various dissident groups when he returned to England and even made another unsuccessful attempt to capture the Duke of Ormond in 1670. Then came his bizarre plan to steal the newly-fashioned Crown Jewels from the Tower of London (following Charles I’s execution in 1649 the original jewels had been melted down).

He joined various dissident groups when he returned to England and even made another unsuccessful attempt to capture the Duke of Ormond in 1670. Then came his bizarre plan to steal the newly-fashioned Crown Jewels from the Tower of London (following Charles I’s execution in 1649 the original jewels had been melted down).

In early 1671, Thomas disguised himself as a parson from a country parish accompanied by his wife. While visiting Jewel House he made the acquaintance of the custodian, Mr. Edwards. The wife was suddenly taken ill (perhaps feigned?) and Mr. Edwards took them to his own home where his wife attended the sick woman. To thank them for their kindness, Thomas returned with a gift and made small talk. Their conversation led to Mr. Edwards mentioning he had a daughter of marriageable age, wherein the “parson” remarked that he had a nephew that he would be happy to introduce her to at 7:00 the next morning.

In early 1671, Thomas disguised himself as a parson from a country parish accompanied by his wife. While visiting Jewel House he made the acquaintance of the custodian, Mr. Edwards. The wife was suddenly taken ill (perhaps feigned?) and Mr. Edwards took them to his own home where his wife attended the sick woman. To thank them for their kindness, Thomas returned with a gift and made small talk. Their conversation led to Mr. Edwards mentioning he had a daughter of marriageable age, wherein the “parson” remarked that he had a nephew that he would be happy to introduce her to at 7:00 the next morning.

On May 9, Thomas returned for the early morning introduction, or at least that was the pretense. Instead he had three friends with him all carrying concealed weapons. They bound Mr. Edwards and seized the jewels. They took the crown, orb and scepter intending to conceal them in a bag, but Mr. Edwards’ son and brother-in-law unexpectedly arrived and interrupted the heist. Thomas flattened the crown with a mallet, shoved the orb down his breeches and off they fled, only to be quickly captured and thrown into prison.

Again, Thomas Blood acted audaciously when he demanded the right to confess his crime to none other than King Charles himself. Charles agreed to meet him. Historic UK records their meeting as such:

Blood was taken to the Palace where he was questioned by King Charles, Prince Rupert, The Duke of York and other members of the royal family. King Charles was amused at Blood’s audacity when Blood told him that the Crown Jewels were not worth the £100,000 they were valued at, but only £6,000!

The King asked Blood “What if I should give you your life?” and Blood replied humbly, “I would endeavour to deserve it, Sire!”

Apparently, King Charles was sufficiently impressed by Blood’s audacity for he pardoned him and returned his Irish land to him – and granted him a yearly pension of five hundred pounds. Some believe the king’s pardon came as a result of a reward for Blood’s services as a Secret Agent.

For years afterwards Thomas Blood was seen around London and at Court. But in 1680 he became ill and died on August 24, 1680. “His reputation for trickery was such that his body was later exhumed by the authorities to verify the fact that he had died.” (Clare County Library)

Robert and John Blood

Two members of the Blood family are recorded in Concord, Massachusetts during the seventeenth century, although probably not the first of the family to immigrate to New England. Brothers John and Robert Blood were proprietors of an independent plantation, which was situated outside the limits of any town. This was an unusual occurrence for that day since in Puritan New England settlements were organized and administered by members of the Church.

The property, referred to as Bloods Farms, was first occupied by the brothers before 1651. They first paid taxes to nearby Billerica until Indian troubles arose and they decided Concord would provide better protection. Billerica objected and had their money refunded by Concord. Later their tax allegiance would return to Concord, but tax problems would continue and become a point of contention with the town governance.

Their property had steadily been increasing in value and thus far the Bloods had managed to pay only minimal tax rates since theirs was an independent plantation. Still the town attempted to exact land taxes from the Bloods. When their land tax bill continued to remain in arrears, Constable John Wheeler was dispatched to seize the property. Arguments and “contumelious speeches” ensued as well as physical violence.

Robert was summoned to court for abusing the constable, his speeches and for vilifying the King’s authority. He was fined and then retaliated by unsuccessfully counter-suing Constable Wheeler for coming to his house “with a great attendance and disturbing him with provoking speeches and striking him at his own house.”

The authorities tried again the following year to exact taxes and were again met with resistance. Robert and his sons were again called to appear before the court, this time fined for “disorderly carnage towards the constables.” A few months later Concord apparently decided the family had some justification for their protests as the fines were reduced. On March 7, 1696, the two parties came to an agreement as to how taxes would be assessed and paid from that date forward.

Robert’s brother John apparently never married and not much is recorded about his life. It is known they appeared together in Lynn, Massachusetts by 1647 and then in Concord by 1649. On October 30, 1682 John was found dead with a gun in his hand, presumed to have accidentally killed himself while hunting. Papers of Samuel Sewall record the following about his death:

Satterday night November 11, (1682) . . . One Blood of Concord about 7 days since or less was found dead in the woods, leaning his Brest on a Logg. Had been seeking some Creatures. Oh! what strange work is the Lord about to bring to pass.

Since John had never married, his estate was passed to Simon and Josiah Blood, Robert’s sons. Two generations later the Bloods Farms had been split up among so many heirs that it ceased to exist.

The family history recorded in The Story of the Bloods is filled with many stories of this family. Evidence exists that the family has contributed much to America through the years – as soldiers, farmers and ranchers, doctors, dentists, miners, oilmen, poets, inventors and more. For example, in the 1860’s, a patent was issued to W.H. Blood for a “clothes-washing machine” and another patent to C F & F Blood for a “washing & wringing machine.” Several members of the family contributed by inventing labor-saving farm equipment.

According to The Story of the Bloods, through the years Blood families used a variety of forenames which were traditional, Biblical, poetic, classic and fanciful. Names like: Aaron, Abel, Alfaretta, Arathusa, Bathsheba, Corvallis, Comfort, Ebenezer, Erastus, Drasella, Obed, Philanda, Submit, Thankful, Mehitable, Narcissa, Paschal and more. The author of the book mused that the prize for the most impressive name was “Lois Jane Amanda Adaline Blood”.

As was the case long ago, family members often married other family members, even first cousins:

Susannah Blood of Carlisle (1776/1818) was born a Blood, died a Blood, was twice married, yet her name was never anything but Blood – Susannah (Blood) (Blood) Blood. She married her first cousin Abel Blood (1771/1803) and when he died married his brother Elnathan Blood (1773/1818).

In that case, Blood was apparently thicker than Blood.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Feisty Females: The Great Western

Today’s “feisty female” has been described as “Amazonian” and a “buxom behemoth”. Some believe she was born Sarah Knight, perhaps of Irish parentage, in 1812 or 1813 in either Tennessee or Missouri – history is unclear as to exactly when and where. She has been referred to variously as “Sarah Bourdett”, “Sarah Borginnis”, “Sarah Bourgette”, “Sarah A. Bowman”, and “Sarah Bowman-Phillips” – but she is best remembered by her nickname “The Great Western”.

Today’s “feisty female” has been described as “Amazonian” and a “buxom behemoth”. Some believe she was born Sarah Knight, perhaps of Irish parentage, in 1812 or 1813 in either Tennessee or Missouri – history is unclear as to exactly when and where. She has been referred to variously as “Sarah Bourdett”, “Sarah Borginnis”, “Sarah Bourgette”, “Sarah A. Bowman”, and “Sarah Bowman-Phillips” – but she is best remembered by her nickname “The Great Western”.

The Great Western Steamship Company was formed in 1836 by a group of Bristol, England investors for the purpose of building a line of steamships which would travel between Bristol and New York. Their theory was that “bigger was better” – in fact they believed that the larger the ship the more fuel efficiently it would run.

When the Great Western made its maiden voyage across the Atlantic in 1838, it was the largest steamship afloat in the world. The ship left Bristol on March 31, 1838 but a fire broke out in the engine room. Although damage was slight, the ship still had to dock at Canvey Island. Several passengers cancelled their bookings and when the Great Western started out again on April 8, there were only seven passengers on board.

When the Great Western made its maiden voyage across the Atlantic in 1838, it was the largest steamship afloat in the world. The ship left Bristol on March 31, 1838 but a fire broke out in the engine room. Although damage was slight, the ship still had to dock at Canvey Island. Several passengers cancelled their bookings and when the Great Western started out again on April 8, there were only seven passengers on board.

The 235-foot long ship was wooden and iron-strapped with side paddle wheels and four masts for auxiliary propulsion and “balance” to keep the paddle wheels in the water and the ship traveling in a straight line. To date it was the most modern technologically designed ship, also called a “floating palace.” The ship caused a stir when it arrived in New York, and apparently not soon forgotten.

In the spring of 1846, Sarah Bourdett (or Bourgette) drove her wagon loaded with cooking equipment into General Zachary Taylor’s army camp in Matamoros, Mexico. She, being at least six feet tall and perhaps two hundred pounds, cut quite an imposing figure. Possibly her impressive size reminded someone of the steamship Great Western, for thereafter that would be her sobriquet.

It is said that upon meeting General Taylor she loudly proclaimed, “If the general would give me a strong pair of tongs, I’d wade that river and whip every scoundrel that dared show himself.” Although the phrase “strong pair of tongs” seemed a little odd, some historians believe that perhaps she was referring to a new style of men’s work pants which were called “tongs.” Nevertheless, she was obviously loaded for bear and ready for action.

Sarah and her husband had first made an appearance in Corpus Christi in 1845 when her husband was part of the part of Taylor’s occupying force after enlisting in Jefferson Barracks, Missouri. It was a common practice that wives were allowed to join the army as cooks or laundresses and accompany their husbands on their missions.

Sarah was an admirer of Zachary Taylor, confident of his leadership skills. President James K. Polk, anticipating problems with the annexation of Texas, sent Taylor to make a stand. When the troops moved to Matamoros to hastily construct Fort Texas, Sarah accompanied them. Supplies had been left behind at Point Isabel so Taylor had to march back and retrieve them. Fort Texas, although well-defended, was lacking supplies.

The 7th Infantry was left behind at the fort. This regiment had earned the nickname of the “Cotton Balers”. During the War of 1812 these troops had made an heroic defense behind cotton bales in the Battle of New Orleans. Major Jacob Brown was the regiment commander. Camp women, including Sarah, remained with the regiment. So Far From God: The U.S. War With Mexico, 1846-1848 describes Sarah:

A strapping, muscular woman six feet in height, she reputedly could trounce any man in the regiment, and once had nearly done so when an unwary soldier made an untoward remark to her back at Corpus Christi. At the Arroyo Colorado she had reportedly offered to cross the stream herself and “straighten out” the entire Mexican army. But despite her strength and pugnacity, she was physically attractive, with dark hair and gray-blue eyes, and she could be tender of heart when the situation called for it….Though officially a noncombatant, she and her like shared the hardships and the dangers of the troops.

General Taylor departed for Port Isabel on May 1, 1846, leaving five hundred soldiers at Fort Brown. On the morning of May 3, the Mexicans began firing upon the fort. Rather than retreat to safe quarters, as would be expected of the women, Sarah continued to serve meals, dress wounds and load rifles. Sarah was said to have been an excellent shot, often seen carrying pistols, and at least one source suggests that she joined in the battle.

The battle continued for seven days and Major Brown was killed. Sarah would be lauded for her heroic efforts in the face of battle. In honor of Major Brown, the fort was renamed to “Fort Brown” and Sarah, a.k.a. “The Great Western” would also become known as “the Heroine of Fort Brown”.

Her story of bravery in the face of danger would be told in newspapers across the country. Some newspaper articles would refer to her as “a queer old woman”, but most lauded her.

After Matamoros, General Taylor crossed the Rio Grande into Mexico and Sarah followed. The Mexicans and Americans clashed in Monterrey, both sides inflicting heavy casualties, but in the end the Americans occupied the city. Sarah set up a restaurant in one of the buildings and called it “The American House.”

Taylor soon moved on to Saltillo and Sarah followed, re-establishing The American House there. She gained a reputation of a willingness to fix meals at any hour of the day or night if a soldier was hungry. The American House would become a “headquarters for everybody” – and not just a restaurant but a bordello as well.

Another battle would soon take place in nearby Buena Vista. For two days the battle raged and Sarah again fed and nursed the troops. One account relates that she had briefly returned to Saltillo when a private from Indiana ran into her restaurant and declared that General Taylor was whipped. Sarah, who practically worshiped Taylor, decked the young man and declared, “There ain’t Mexicans enough in Mexico to whip old Taylor. You just spread that rumor and I’ll beat you to death.” The rumor turned out to be untrue as Taylor was victorious.

At some point Sarah’s husband was perhaps killed, as some accounts have suggested. When the Mexican War ended with the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, troops were next dispatched to defend travelers heading to the gold fields of California. Sarah wanted to accompany them but her husband was gone now, and the rule had been as long as the husband was a soldier the wife could travel with his regiment.

To circumvent the regulations, Sarah proclaimed, “Who wants a wife with $15,000 and the biggest leg in Mexico? Come, my beauties, don’t all speak at once. Who is the lucky man?” A dragoon by the name of Davis stepped forward. According to More Than Petticoats: Remarkable Texas Women:

One brave private came forward and said, “I have no objections to making you my wife, if there is a clergyman here who would tie the knot.” To which The Great Western replied, “Bring your blanket to my tent tonight and I will learn you to tie a knot that will satisfy you, I reckon!”

For two short months, she would be Sarah Davis, until she met another man who caught her fancy. Davis was dispensed with and, for several months she presumably lived with the other man. Sarah made her way to El Paso in 1849 where she briefly ran a hotel for travelers heading to California. Then, with another man, possibly Juan Duran, she went to Socorro, New Mexico, as evidenced by the 1850 census (Sarah had reverted to her first husband’s name apparently, listed as “Sarah Bourgette”). Also listed with them are five young girls which some believe might have been frontier orphans. Nancy Skinner, two years old in 1850, would remain with Sarah as an adopted daughter.

Less than two years later Sarah married Albert Bowman and moved to Fort Yuma. Sarah worked in the hospital and served as a cook for the officers. Later she and Albert would continue to move with troops throughout Arizona. When gold was discovered in Fort Yuma the two returned. Albert was several years younger than Sarah and in 1864 he ran off with a younger woman. Now Sarah was left alone with several adopted Mexican and Indian children to raise.

Historical facts are unclear as to when or how Sarah died, but some accounts say she died of a tarantula bite. She was buried in the Fort Yuma cemetery on December 23, 1866 with full military honors. Twenty-four years later all bodies buried in the cemetery were exhumed and moved elsewhere. Sarah’s body was sent to The Presidio in California – her tombstone lists her name as “Sarah A. Bowman”, but to so many who knew her throughout her illustrious life, she would always be known as “The Great Western.”

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

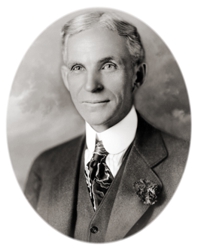

Motoring History: Henry Ford (Part I)

Henry Ford was a lot of things: industrialist, self-made man, wealthy and successful, maker of men (as he liked to say). His business philosophy became known as “Fordism” – mass produce inexpensive goods and pay high wages. It seemed he had an opinion on just about everything in the world. After he became successful, he printed his own newspaper espousing those (often controversial) views and opinions.

Henry Ford was a lot of things: industrialist, self-made man, wealthy and successful, maker of men (as he liked to say). His business philosophy became known as “Fordism” – mass produce inexpensive goods and pay high wages. It seemed he had an opinion on just about everything in the world. After he became successful, he printed his own newspaper espousing those (often controversial) views and opinions.

Henry Ford was born on July 30, 1863 to parents William and Mary (Litogot) Ford in Wayne County, Michigan not far from Detroit. His father was born in Cork County, Ireland and his mother was the daughter of Belgian immigrants. Henry was their eldest and four children followed him. William, a farmer, expected his children would contribute by working on the family farm. But, Henry was different – he was a tinkerer.

Henry Ford was born on July 30, 1863 to parents William and Mary (Litogot) Ford in Wayne County, Michigan not far from Detroit. His father was born in Cork County, Ireland and his mother was the daughter of Belgian immigrants. Henry was their eldest and four children followed him. William, a farmer, expected his children would contribute by working on the family farm. But, Henry was different – he was a tinkerer.

This article is no longer available at this site. However, it will be enhanced and published later in a future issue of Digging History Magazine, our new monthly digital publication available by individual purchase or subscription. To see what the magazine is all about you can preview issues at our YouTube Channel. Subscriptions are affordable, safe and easy to purchase and the best deal for getting your “history fix” every month.

This article is no longer available at this site. However, it will be enhanced and published later in a future issue of Digging History Magazine, our new monthly digital publication available by individual purchase or subscription. To see what the magazine is all about you can preview issues at our YouTube Channel. Subscriptions are affordable, safe and easy to purchase and the best deal for getting your “history fix” every month.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Surname Saturday: Gildersleeve

According to Bardsley’s A Dictionary of English and Welsh Surnames, the Gildersleeve surname is a nickname meaning “with sleeves braided with gold”. One source refers to it as an English nickname for an ostentatious dresser. Originally, the name was derived from the Middle English nickname “Gyldenesleve” or “golden sleeve” – “Gyld” (gold) + “Slef” (sleeve).

Some of the first records of the surname date back to 1273 for a Roger Gyldensleve from County Norfolk, and in 1421 John Gildensleve was a Fellow of College of the Holy Cross, Atleburgh, County Norfolk. Other variations of the surname include “Gildensleeve”, “Gyldersleive”, “Gildersleeve” and “Gildersleive”, along with similar names such as “Gilder”, “Gildersome”, Gyldenloeve” and “Gildensholme”.

The first New England immigrant and the progenitor of all American Gildersleeves was Richard Gildersleeve. Even though he is barely mentioned in early American history, he played a significant role in the country’s early days. The Declaration of Independence would be tinged with the sentiments expressed by Richard Gildersleeve over one hundred years before it was signed in 1776.

Richard Gildersleeve

Richard Gildersleeve was born in 1601 in County Suffolk, England. Little is known about the early years of Richard, but at some point prior to 1635, he joined other like-minded believers in the great Puritan exodus, desiring to escape religious persecution. It is believed that Richard was an English yeoman, a commoner who cultivated the land.

Upon arrival in New England, he first dwelt in Watertown, Massachusetts. By the time Richard arrived, the Puritans of the Massachusetts Bay Colony were already setting up a theocratic government. If one wanted to vote and participate in civic affairs, church membership was required. Settlers who had fled England to avoid religious persecution would begin to experience it again. “The ministers ruled supreme, minute laws interfered with personal liberty, amusements were studiously discouraged and devotional exercises substituted in their stead.” (Gildersleeve Pioneers, p. 21).

Upon arrival in New England, he first dwelt in Watertown, Massachusetts. By the time Richard arrived, the Puritans of the Massachusetts Bay Colony were already setting up a theocratic government. If one wanted to vote and participate in civic affairs, church membership was required. Settlers who had fled England to avoid religious persecution would begin to experience it again. “The ministers ruled supreme, minute laws interfered with personal liberty, amusements were studiously discouraged and devotional exercises substituted in their stead.” (Gildersleeve Pioneers, p. 21).

To flee New England religious persecution, Richard joined other Puritans who decided to leave Massachusetts and settle the newly-formed Connecticut colony. They departed in the autumn of 1635 with their oxen and cattle, while food supplies and household goods were loaded onto ships. After a month-long trek, the group reached Wethersfield, but the ship was delayed due to a storm and the Connecticut River froze early, leaving the new residents of Wethersfield without the food and household goods they had expected to arrive. The pioneers had no choice but to build cabins and wait out the long and dreary winter as best they could.

Richard Gildersleeve would become “one of the most interesting pioneers of the first settlements of Massachusetts, Connecticut, New Haven and Long Island, N.Y.” (Gildersleeve Pioneers, p. 22). Early Connecticut records indicate that Richard might have been a little “rough around the edges.” Summoned by the General Court to provide an inventory of goods, he was late in responding to the order – he had to be reminded by the constable to appear. He also had a dispute with a neighbor, Jacob Waterhouse.

Waterhouse owed Richard a considerable sum of money. Richard had purchased a hog from his neighbor and apparently refused to pay for it until Waterhouse paid his debt. Each man sued the other and in court each lost his case, which perhaps didn’t sit well with Richard. After freely expressing his opinions as to his treatment in court, he was summoned to court where he was accused of delivering “pernicious speeches, tending to the detriment and dishonor of this Commonwealth”. He was fined forty shillings, with a sort of “probation” attached — an additional twenty pounds — until the next general court would be held. Richard eventually paid the entire fine, but as it turns out he had probably been planning to leave the Commonwealth altogether after residing there for four years.

It had not been an easy four years either. The Pequot Indians terrorized the nascent colony, and wild animals, especially bears, were prevalent. A girl shot one from the doorway of her home and remarked, “He was a good Fatte one and kept us all in meat for a good while.” (Wethersfield and her Daughters, 1634-1934). In April of 1637, William Swayne, a neighbor of Richard’s was attacked by Pequots and his two daughters were kidnapped.

His legal troubles and the ever-present dangers notwithstanding, the town of Wethersfield had problems of its own in regards to discontented parishioners. He left Wethersfield and headed to New Haven, where he participated in the founding and organization of the new colony, settling in Stamford. The move must have done wonders for Richard because his standing in the new colony was elevated and he began to hold a succession of various offices (including fence-viewer and deputy of the New Haven general court).

Richard migrated once again in 1644 to Hempstead, Long Island, New York and soon became one of the largest and most influential land owners. He served as a Dutch magistrate under Governor Stuyvesant. Perhaps not so admirably, however, the first instance of Quaker persecution by the Dutch (and remember Richard was a Puritan) was led by none other than Magistrate Richard Gildersleeve:

[Quakers] ran against a rock in the person of Magistrate Gildersleeve. As soon as the latter heard of the coming of Hodgson, he issued a warrant to the constable to arrest the preacher. Already a place had been appointed for the holding of a meeting, and there the constable found the Quaker, “pacing the orchard alone in quiet meditation.” He at once seized hold of him and hauled him off to the magistrate. But as it was just time for worship, the conscientious justice locked him up in his private house – for Hempstead had no jail – and went off to hear Mr. Denton preach. While the magistrate was thus performing his religious duty, the Quaker got the better of him; for in some way, probably by shouting in a loud voice from the window of his prison, he succeeded in collecting a crowd of listeners, who, gathering before the house, “staid and hearth the truth declared.” (The New England Magazine: An Illustrated Monthly – Volume 7)

Of course, Richard was not pleased to have been outwitted. Hodgson was seized by the sheriff and taken to New Amsterdam, thrown in prison and fined six hundred guilders.

During the years preceding his death in 1681, Richard Gildersleeve was often called upon to serve in other civic offices and settle disputes with Indians, which, of course, meant that Richard Gildersleeve had finally obtained a measure of community and civic stature – with age came wisdom and forbearance. He would witness controversies that arose when the English sought to gain jurisdiction over the Dutch Long Island settlements.

When the Long Island towns came under English jurisdiction more controversies arose. On October 9, 1669, Richard Gildersleeve met with other aggrieved parties of the eight towns and drew up what was called the “Hempstead Petition”. It appears to have been a case of “taxation without representation” – something that would agitate colonists in the next century and incite the Revolutionary War.

One family historian was so bold as to suggest that the Hempstead Petition marked the beginning of American independence. The historian lauded his ancestor:

Richard Gildersleeve was a yeoman, the best stock of English blood, the bone and sinew also of English strength. It was his particular destiny to play an important part in the history of political liberty. He was one of the strongest links of that long chain of events that marked the slow development of political liberty with the consequent foundation of the greatest republic in history. The story of his life was a constant struggle for his fellow men against despotism and tyranny. The crowning feature of his struggle was the part he took as an American pioneer and leader of men in personally experiencing and personally directing a notable contest of Long Island colonials against overbearing disregard of the dearly bought liberties of himself and fellow colonists.

In the long chain of events that marked the slow progress of political liberty from the Magna Carta in 1215 to the Declaration of Independence in 1776, he personally forged a strong link. He led in the making of one of the documents that showed the continued development of political liberty in the New World after it had been checked in England by the Stuart kings. This document, the Hempstead Petition of 1669, marks one of the beginnings of American independence. (Gildersleeve Pioneers, pp. 15-16)

That is quite a statement regarding a person who is barely mentioned in early American history. Following Richard Gildersleeve’s death, “The Charter of Liberties and Privileges” was drawn up in 1683. Known also as the Dongan Charter, it was the first time the term “the people” was mentioned in any form in regards to the powers (or limits) of government. Thank you Richard Gildersleeve.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

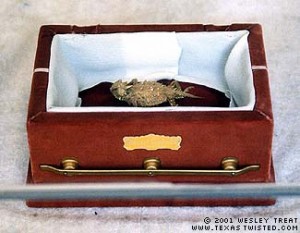

Far-Out Friday: Old Rip the Horned Toad

Although the term “cornerstone” is referenced several times in the Bible, the exact origin of a ceremony laying a building cornerstone and placing items in it (a “time capsule”) is vague, but perhaps began to be practiced as many as five thousand years ago. Time Capsules: A Cultural History suggests that:

Although the term “cornerstone” is referenced several times in the Bible, the exact origin of a ceremony laying a building cornerstone and placing items in it (a “time capsule”) is vague, but perhaps began to be practiced as many as five thousand years ago. Time Capsules: A Cultural History suggests that:

Time capsules can embody the highest technical and cultural aspirations of civilization, like the World’s Fairs where they are sometimes exhibited. They are commonly featured as institutional publicity promotions, public relations activities, carnival-type attractions, or even the very familiar, de rigueur civic commemorative rituals. They are convenient devices (literal or metaphorical) for us to commemorate hopes and evidence by leaving them for possible futures. Influential groups of twentieth century savants and promoters organized a few noteworthy time capsule projects and attempted to preserve them for future recipients. More often, people have been content to seal up smaller cultural samples, multitudes of which serve as “garden-variety” time capsules – modest shorter span memorials.

Time capsules can embody the highest technical and cultural aspirations of civilization, like the World’s Fairs where they are sometimes exhibited. They are commonly featured as institutional publicity promotions, public relations activities, carnival-type attractions, or even the very familiar, de rigueur civic commemorative rituals. They are convenient devices (literal or metaphorical) for us to commemorate hopes and evidence by leaving them for possible futures. Influential groups of twentieth century savants and promoters organized a few noteworthy time capsule projects and attempted to preserve them for future recipients. More often, people have been content to seal up smaller cultural samples, multitudes of which serve as “garden-variety” time capsules – modest shorter span memorials.

This article is no longer available for free at this site. It was re-written and enhanced (5-page article), complete with footnotes and sources and has been published in the September 2018 issue of Digging History Magazine. Should you prefer to purchase the article only, contact me for more information. The September issue also featured several articles about Oklahoma, including some focused on the state’s radical (Socialist) past (“When Red Meant Radical: Oklahoma’s Red Dirt Socialism” and “Give Me That Old Time Socialism”).

This article is no longer available for free at this site. It was re-written and enhanced (5-page article), complete with footnotes and sources and has been published in the September 2018 issue of Digging History Magazine. Should you prefer to purchase the article only, contact me for more information. The September issue also featured several articles about Oklahoma, including some focused on the state’s radical (Socialist) past (“When Red Meant Radical: Oklahoma’s Red Dirt Socialism” and “Give Me That Old Time Socialism”).

I invite you to check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? That’s easy if you have a minute or two. Here are the options (choose one):

- Scroll up to the upper right-hand corner of this page, provide your email to subscribe to the blog and a free issue will soon be on its way to your inbox.

- A free article index of issues is available in the magazine store, providing a brief synopsis of every article published in 2018. Note: You will have to create an account to obtain the free index (don’t worry — it’s easy!).

- Contact me directly and request either a free issue and/or the free article index. Happy to provide!

Thanks for stopping by!

Ghost Town Wednesday: Fordlandia (Part One)

Even the most successful business people make mistakes or propose ill-conceived ideas. Such was the case when mega-successful Henry Ford conceived a plan to plant and maintain his own rubber plantation in Brazil. At the time, Ford Motor Company was probably one of the largest consumers of rubber in America, used in the production of their wildly popular Model T’s.

Even the most successful business people make mistakes or propose ill-conceived ideas. Such was the case when mega-successful Henry Ford conceived a plan to plant and maintain his own rubber plantation in Brazil. At the time, Ford Motor Company was probably one of the largest consumers of rubber in America, used in the production of their wildly popular Model T’s.

Historically, the Amazon had long been the major source for the world’s rubber supply – that is until a Brit by the name of Henry Wickham stole some seeds and sold them to the Royal Botanic Garden. The rubber plants did very well and soon they were sent to British colonies in the Far East. As it turned out, the Far East was a more hospitable place for rubber plantations than were the jungles of the Amazon.

Historically, the Amazon had long been the major source for the world’s rubber supply – that is until a Brit by the name of Henry Wickham stole some seeds and sold them to the Royal Botanic Garden. The rubber plants did very well and soon they were sent to British colonies in the Far East. As it turned out, the Far East was a more hospitable place for rubber plantations than were the jungles of the Amazon.

This article is no longer available at this site, but will be published in a future issue of Digging History Magazine. I invite you to check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

This article is no longer available at this site, but will be published in a future issue of Digging History Magazine. I invite you to check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Tombstone Tuesday: Lycurgus Dinsmore Bigger

Lycurgus Dinsmore Bigger was born September 19, 1843 in Blue Ball, Warren County, Ohio to parents James and Elizabeth (McCandless) Bigger. I wouldn’t pretend to know the origin of his first name. Lycurgus, however, is a common name in Greek mythology and in Greek the name is derived from “lycos urgos” or “he who keeps the wolves away.” Dinsmore is probably a family name as it was customary to give children middle names which were family names or surnames of ancestors.

Lycurgus Dinsmore Bigger was born September 19, 1843 in Blue Ball, Warren County, Ohio to parents James and Elizabeth (McCandless) Bigger. I wouldn’t pretend to know the origin of his first name. Lycurgus, however, is a common name in Greek mythology and in Greek the name is derived from “lycos urgos” or “he who keeps the wolves away.” Dinsmore is probably a family name as it was customary to give children middle names which were family names or surnames of ancestors.

I ran across this name when I was researching last week’s Tombstone Tuesday article for Bigger Head. The history of Lycurgus Dinsmore Bigger presented a challenge to find meaningful (and accurate) information about his life. It does appear that at some point that either he decided to drop “Lycurgus” or there was someone else named “Dinsmore Bigger”. I found a couple of books on the genealogies of the Loomis and Williams (wife’s ancestors) families which included a brief record for Lycurgus and his family.

I ran across this name when I was researching last week’s Tombstone Tuesday article for Bigger Head. The history of Lycurgus Dinsmore Bigger presented a challenge to find meaningful (and accurate) information about his life. It does appear that at some point that either he decided to drop “Lycurgus” or there was someone else named “Dinsmore Bigger”. I found a couple of books on the genealogies of the Loomis and Williams (wife’s ancestors) families which included a brief record for Lycurgus and his family.

Did you enjoy this article snippet? Want to know more? This article has been significantly updated (now a 5000+ word article) with new research and published in the November-December 2019 issue of Digging History Magazine. The magazine is on sale in the Digging History Magazine store and features these stories:

- The Burr Conspiracy: Treason or Prologue to War

- Finding War of 1812 Records (and the stories behind them)

- Sarah Connelly, I Feel Your Pain (Adventures in Research: 1812 Pension Records)

- Essential Skills for Genealogical Research: Noticing Notices

- Bullets, Battles and Bands: The Role of Music in War

- Feisty Female Sheriffs: Who Was First?

- The Dash: Bigger Family: (A Bigger and Better Story)

- Book reviews, research tips and more

Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 85-100+ pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 85-100+ pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Motoring History: The Race That Changed Everything

In the history of the Ford Motor Company, they call it the “race that changed everything.” Henry Ford had founded the Detroit Automobile Company on August 5, 1899 and in January of 1901 the company was dissolved. Henry Ford had already reinvented himself when he left home at age 16 and headed to Detroit to make his mark on the world. In 1901 he would have to begin to reinvent himself once again.

In the history of the Ford Motor Company, they call it the “race that changed everything.” Henry Ford had founded the Detroit Automobile Company on August 5, 1899 and in January of 1901 the company was dissolved. Henry Ford had already reinvented himself when he left home at age 16 and headed to Detroit to make his mark on the world. In 1901 he would have to begin to reinvent himself once again.

On October 10, 1901 the Detroit Driving Club was holding a twenty-five lap racing event at the Grosse Point Race Track. At that time, Alexander Winton had the best-selling gas-fueled passenger cars in America – he was also the best race driver. But Winton wasn’t really interested in this particular race, that is until he struck a deal with race officials who allowed him to pick out the trophy (which, of course, he presumed to win). There was also a cash prize of one thousand dollars.

On October 10, 1901 the Detroit Driving Club was holding a twenty-five lap racing event at the Grosse Point Race Track. At that time, Alexander Winton had the best-selling gas-fueled passenger cars in America – he was also the best race driver. But Winton wasn’t really interested in this particular race, that is until he struck a deal with race officials who allowed him to pick out the trophy (which, of course, he presumed to win). There was also a cash prize of one thousand dollars.

This article is no longer available at this site. However, it will be enhanced and published later in a future issue of Digging History Magazine, our new monthly digital publication available by individual purchase or subscription. To see what the magazine is all about you can preview issues at our YouTube Channel. Subscriptions are affordable, safe and easy to purchase and the best deal for getting your “history fix” every month.

This article is no longer available at this site. However, it will be enhanced and published later in a future issue of Digging History Magazine, our new monthly digital publication available by individual purchase or subscription. To see what the magazine is all about you can preview issues at our YouTube Channel. Subscriptions are affordable, safe and easy to purchase and the best deal for getting your “history fix” every month.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Surname Saturday: Coffin

Coffin

This family can trace its roots back to Sir Richard Coffin, a knight who was with William the Conqueror when he went to England in 1066. Many historians agree that the surname is derived from the French word “cofin” or “coffin”, which was derived from the Latin word “cophinus” and all mean “basket”. According to William Arthur’s Etymological Dictionary of Family and Christian Names, the Welsh derivation of the surname is “Cyffin”, which “signifies a boundary, a limit, a hill; cefyn, the ridge of a hill.”

Presumably, the progenitor of most, if not all, American Coffin families was Tristram Coffyn who was born in 1605 (or 1606 or 1609 according to various sources). He immigrated to the New England in 1642 with his wife Dionis (Stevens) and their five children, his mother (a widow) and his two unmarried sisters.

Tristram Coffyn

Tristram Coffyn and his family (and extended family) settled in Haverhill, Massachusetts in 1642. Historical tradition holds that Tristram was the first to plow land in Haverhill, having constructed his own plow. He removed to Newbury in 1648 where he sold wine and liquor, and apparently Dionis “oversold”:

Tristram Coffyn and his family (and extended family) settled in Haverhill, Massachusetts in 1642. Historical tradition holds that Tristram was the first to plow land in Haverhill, having constructed his own plow. He removed to Newbury in 1648 where he sold wine and liquor, and apparently Dionis “oversold”:

In September, 1643, his wife Dionis was prosecuted for selling beer for two pence a quart, while the regular selling price was but two pence, but she proved that she had put six bushels of malt into the hogshead, while the law required only four, and she was discharged. (The American Biography: A New Cyclopedia, Volume 12)

In 1659, Tristram and some of his friends and associates planned the purchase of Nantucket Island, fleeing religious persecution. Thomas Macy, one of original Nantucket settlers, “fled from the officers of the law and sold his property and home rather than submit to tyranny, which punished a man for being hospitable to strangers in the rainstorm even though the strangers be Quakers.” The cost of the island was said to have been £30 and two beaver hats.

In 1659, Tristram and some of his friends and associates planned the purchase of Nantucket Island, fleeing religious persecution. Thomas Macy, one of original Nantucket settlers, “fled from the officers of the law and sold his property and home rather than submit to tyranny, which punished a man for being hospitable to strangers in the rainstorm even though the strangers be Quakers.” The cost of the island was said to have been £30 and two beaver hats.

Tristram was thirty-seven years old when he settled on Nantucket and within the first year became the richest proprietor on the island. Together with his son Peter’s land, the family owned approximately one-fourth of the island. He served at various times as both chief magistrate and commissioner of Nantucket and another island, Tuckernuck, which was exclusively owned by the Coffin family. His children married into other prominent families on the island like the Starbucks and Swains.

Tristram Coffyn died on October 2, 1681 and is buried on the island. It is worthy of note that his descendants which remained on the island had very little to do with the Revolutionary War. While British ships did visit, the inhabitants of Nantucket retained a careful and deliberate neutrality.

The two men highlighted below were descended from Tristram Coffyn, he being their sixth great grandfather (if my calculations are correct). One made his mark in the American automotive industry and the other in aviation.

Howard Earle Coffin

Howard Earle Coffin was born on September 6, 1873 in West Milton, Ohio and raised in Ann Arbor, Michigan. He attended the University of Michigan where he studied mechanical engineering. There he constructed his first steam-powered automobile, using it to deliver mail around the town. He later built an internal combustion engine.

Howard Earle Coffin was born on September 6, 1873 in West Milton, Ohio and raised in Ann Arbor, Michigan. He attended the University of Michigan where he studied mechanical engineering. There he constructed his first steam-powered automobile, using it to deliver mail around the town. He later built an internal combustion engine.

He graduated in 1902 and went to work for Oldsmobile as chief experimental engineer and later worked for E.R. Thomas-Detroit Motor Company. In 1906 he helped found Chalmers-Detroit Motor Company (later Chrysler) and served as its first vice president. In 1909 he helped found yet another car company, the Hudson Motor Car Company, where he served as both vice president and chief engineer.

He also initiated standards for materials and design specifications which helped the automobile industry grow. He was known as the “Father of Standardization”, a very successful millionaire early in his career.

He became an unofficial member of Woodrow Wilson‘s war cabinet (Council of National Defense) after the United States reluctantly joined World War I. After the war, Howard helped found the American commercial aviation industry by serving as board chairman of National Air Transport Company, which would later become United Airlines. He also served on the Morrow Board, named by President Calvin Coolidge, to make recommendations about airline safety and standards.

Automobile racing drew Howard to Georgia where he would reside the rest of his life. He purchased land on Sapelo Island, built a palatial home, and was host to dignitaries such as Charles Lindbergh and Presidents Coolidge and Hoover. He continued to purchase land in Georgia and was responsible for developing coastal Georgia into a vacation and tourism destination.

Howard Earle Coffin died at the age of sixty-four on November 21, 1937.

Frank Trenholm Coffyn

Frank Trenholm Coffyn was born on October 24, 1878 in Charleston, South Carolina. In December of 1909, Frank became interested in aviation after seeing an exhibition in New York City. His father George knew one of the executives of the Wright Company who arranged a meeting with none other than Wilbur Wright. Wright must have been impressed because he invited Frank to Dayton in 1910 to begin flight instruction — Orville trained him.

During his career he flew as part of the Wright Exhibition Team, delivered aircraft to the United States Army in Texas, flew as a stunt pilot – just once flying under the Brooklyn Bridge. He served as a United States Army flight instructor in World War I and tried his hand at acting in silent movies in the 1920’s. He sold aircraft for the Burgess Company and in 1944 at the age of sixty-six, Frank obtained his helicopter pilot’s license. According to his obituary, his helicopter license was the third issued and his airplane pilot’s license was number twenty-six, definitely an aviation pioneer.

Frank’s life was celebrated on “This is Your Life”, a 1950’s television show hosted by Ralph Edwards. Historic footage of him flying as part of the Wright Exhibition Team was featured, as well as surprise guest Roy Knabenshue who was Frank’s boss when he flew with the team.

When he died on December 10, 1960 at the age of eighty-two, at that time he was the oldest licensed pilot and the last surviving member of the Wright Exhibition Team.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!