Lillian Moller Gilbreth was born on May 24, 1878 in Oakland, California to parents William and Anne Moller. She grew up in a Victorian, German-American home, the second and oldest of ten children (the first child died in infancy). Lillie (she later changed her name to Lillian) was shy and introverted, so much so that she was schooled at home by her mother until the age of nine. Even then Lillian wasn’t able to “fit in” – academically she excelled but socially she was awkward. Home and domestic life were more suited to her, learning to sew and care for her siblings.

Lillian Moller Gilbreth was born on May 24, 1878 in Oakland, California to parents William and Anne Moller. She grew up in a Victorian, German-American home, the second and oldest of ten children (the first child died in infancy). Lillie (she later changed her name to Lillian) was shy and introverted, so much so that she was schooled at home by her mother until the age of nine. Even then Lillian wasn’t able to “fit in” – academically she excelled but socially she was awkward. Home and domestic life were more suited to her, learning to sew and care for her siblings.

By the time she entered high school she was actually eager to attend, although she still experienced social awkwardness with classmates. She dreaded the day when she would have to consider delving into the world of dating and courtship – she was petrified of boys and thought herself unattractive.

By the time she entered high school she was actually eager to attend, although she still experienced social awkwardness with classmates. She dreaded the day when she would have to consider delving into the world of dating and courtship – she was petrified of boys and thought herself unattractive.

While she resigned herself to perhaps remaining single, she yearned for something beyond remaining with her family to care for them and leading the life of a spinster. Writing, especially poetry, was a way for her to express herself, however. In the end, writing was what drew her out and she later found acceptance with her peers. One of her English teachers encouraged her to pursue a literary career. She admired her mother but she was inspired by her mother’s sister, Dr. Lillian Powers, a psychiatrist.

As the Victorian era came to a close in the late nineteenth century and the twentieth century dawned, there was a demographic shift in America from rural to urban – the country would soon become more mechanized. Social mores were changing as well. It became more acceptable for young ladies to pursue careers, although they weren’t welcomed as equals to their male counterparts in business and industry for years to come.

When she decided she wanted to pursue an academic career, her parents weren’t exactly thrilled, although they acquiesced when she rationalized to them that she would educate herself to become a teacher and to later care for her own children when she married. Deep down, however, Lillian hoped to avoid marriage and motherhood for awhile, if not altogether.

Lillian excelled at Berkeley, finishing at the top of her class with a degree in English. After graduating she wanted to continue her educational pursuits, but she wanted to attend school in the East, enrolling in Columbia’s Psychology Department. She had family in New York, but still her parents were concerned for her. She threw herself wholeheartedly into her studies, often skipping meals until she grew thin. When cold weather set in she became ill and had to return home to California.

Still determined to pursue a graduate education, she enrolled at Berkeley and planned to write a master’s thesis on Elizabethan literature. Having completed that degree, Lillian wanted to take a trip to Europe with friends before she began her doctoral program. Her parents would not allow here to travel un-chaperoned so one of the teachers at Oakland High School, Minnie Bunker, accompanied them. Before heading overseas, however, they made a stop in Boston to tour the city and meet Minnie’s family. There Lillian would meet her future husband, Frank Bunker Gilbreth, Minnie’s nephew.

Frank Gilbreth, being extremely gregarious and extroverted, was the polar opposite of Lillian, yet they later forged not only a strong and successful relationship as husband and wife, but as business partners. After their engagement, even before marriage, they forged a partnership. Frank was in the construction business and he relied on Lillian to edit manuscripts and prepare advertising materials. During their honeymoon trip, Frank requested of her a list of qualifications she was bringing to their “partnership”. However formal and rigid that might sound, the two made it work for years to come.

Frank Gilbreth, being extremely gregarious and extroverted, was the polar opposite of Lillian, yet they later forged not only a strong and successful relationship as husband and wife, but as business partners. After their engagement, even before marriage, they forged a partnership. Frank was in the construction business and he relied on Lillian to edit manuscripts and prepare advertising materials. During their honeymoon trip, Frank requested of her a list of qualifications she was bringing to their “partnership”. However formal and rigid that might sound, the two made it work for years to come.

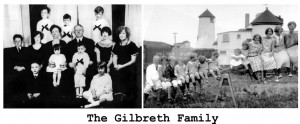

Frank wanted to excel in the field of industrial management and motion study, and he spent a considerable amount of time away from home through the years of their marriage. He published several books and training materials over the year, under his name which were in actuality largely compiled and written by Lillian (while having babies, recovering from pregnancy and having yet another child soon after — thirteen in all, with eleven living to adulthood). In those times, of course, it wasn’t acceptable for women to receive recognition for achievements outside the societal norms of wife and mother.

Their business was successful, however, and Lillian added her own theories – she injected psychology, a human touch to the field of motion study and industrial management. Her profile would eventually be raised in that field, however, after Frank died suddenly in 1924, leaving her as the sole breadwinner for her large family. Although it was a struggle at times, Lillian Gilbreth more than arose to the occasion time and again over the remaining years of her long career.

When the Great Depression hit America, she was able to market herself effectively as she helped women stretch their money farther during that trying time. In 1926 she performed market research for Johnson & Johnson (sanitary napkins) and later helped improve management practices at Macy’s. She worked as an industrial engineer for General Electric, helping to re-invent and re-design the modern kitchen. Her work was thorough and meticulous as she interviewed over four thousand women to garner information regarding proper heights for stoves, sinks and other kitchen appliances and fixtures.

She designed an electric mixer, shelves for refrigerator doors and a trash can with a foot pedal and made “tweaks” and improvements on other appliances and devices. Amazingly, as skilled as she was with innovation in the kitchen, Lillian never learned to cook (for years her mother-in-law helped with household management). According to Lillian Gilbreth: Redefining Domesticity, “[P]rivately her children had referred to one of her culinary experiments as ‘Dog Vomit on toast’”.

She designed an electric mixer, shelves for refrigerator doors and a trash can with a foot pedal and made “tweaks” and improvements on other appliances and devices. Amazingly, as skilled as she was with innovation in the kitchen, Lillian never learned to cook (for years her mother-in-law helped with household management). According to Lillian Gilbreth: Redefining Domesticity, “[P]rivately her children had referred to one of her culinary experiments as ‘Dog Vomit on toast’”.

She was known as “Mother” for several things – “Mother of the Year” (1957), “Mother of Industrial Psychology” (1954), “Mother of Modern Management” and “the greatest woman engineer in the world” (1954). She received her doctoral degree before Frank passed away and later received over twenty honorary degrees and scores of awards for her work, even though she struggled early on to make a name for herself in the male-dominated field she chose to pursue.

Lillian raised successful children and worked tirelessly for years beyond the “normal” age of retirement. At the age of eighty-seven she was still traveling in both the United States and Europe to present lectures – even though her family encouraged her to slow down she continued to work. It was only after one of her children, Martha, died of cancer at the age of fifty-nine that her health began to decline. She moved in with one of her daughters in Arizona and later to a nursing facility. She died on January 2, 1972 at the age of 93.

In the book, Lillian Gilbreth: Redefining Domesticity, the author sums up her life this way:

Lillian Gilbreth never saw womanhood as biological destiny. As she modeled a strenuous life for her children, she proved that one could balance intellectual and family life, home and work, family and career on terms of ones choosing. She raised the status of homemakers by treating them as specialized experts of important work. But she also simplified housework enough to allow women to leave the home to achieve status and economic autonomy through other endeavors. If some of her idea seemed contradictory, she was proof of their liberating force.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Trackbacks/Pingbacks