Wild West Wednesday: Henry Andrew “Heck” Thomas

One of the West’s most effective lawmen, Henry Andrew “Heck” Thomas, was born on January 3, 1850 in Athens, Georgia to parents Lovick and Martha Thomas. When the Civil War broke out, Heck’s father and two of his uncles joined the Confederate Army. Heck was twelve years old and he accompanied them as a courier, traveling to the battlefields of Virginia.

One of the West’s most effective lawmen, Henry Andrew “Heck” Thomas, was born on January 3, 1850 in Athens, Georgia to parents Lovick and Martha Thomas. When the Civil War broke out, Heck’s father and two of his uncles joined the Confederate Army. Heck was twelve years old and he accompanied them as a courier, traveling to the battlefields of Virginia.

Heck was present at the Second Battle of Bull Run. When Union General Philip Kearny was killed, General Robert E. Lee personally ordered Heck to return Kearny’s horse and belongings to his widow. Years later he recounted the story to his brother Lovick:

One evening while the fight was going on or, rather, just before dark, a soldier came to the rear where Uncle Ed’s baggage and the darkies and I were, leading a black horse with saddle and bridle. He brought also a sword. Just after this, Stonewall Jackson crossed over into Maryland and captured the city of Frederick; that was after taking Harper’s Ferry (now West Virginia) and about 14,000 federal prisoners. These prisoners were held by Uncle Ed’s brigade, while the army was fighting the Battle of Sharpsburg. We could see the smoke and hear they cannon from Harper’s Ferry. While we were at Harpers Ferry, General Lee sent an order to uncle Ed for the horse and equipments. I carried them forward, and it was one of the proudest minutes of my life when I found myself under the observation of General Robert E. Lee. Then General Lee sent the horse and everything through the lines , under a flag of truce, to General Kearney’s [sic] widow. I had ridden the horse and cared for him up to that time, and I hated to part with him.

One evening while the fight was going on or, rather, just before dark, a soldier came to the rear where Uncle Ed’s baggage and the darkies and I were, leading a black horse with saddle and bridle. He brought also a sword. Just after this, Stonewall Jackson crossed over into Maryland and captured the city of Frederick; that was after taking Harper’s Ferry (now West Virginia) and about 14,000 federal prisoners. These prisoners were held by Uncle Ed’s brigade, while the army was fighting the Battle of Sharpsburg. We could see the smoke and hear they cannon from Harper’s Ferry. While we were at Harpers Ferry, General Lee sent an order to uncle Ed for the horse and equipments. I carried them forward, and it was one of the proudest minutes of my life when I found myself under the observation of General Robert E. Lee. Then General Lee sent the horse and everything through the lines , under a flag of truce, to General Kearney’s [sic] widow. I had ridden the horse and cared for him up to that time, and I hated to part with him.

Did you enjoy this article snippet? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. This article has been updated with new research and published in the January-February 2020 issue of the magazine. The magazine is on sale in the Digging History Magazine store and features these stories (140+ pages of stories, no ads):

This issue of Digging History Magazine is PACKED with stories! Generally, the main theme is the U.S. Census, but there are articles for both genealogists and history buffs to enjoy:

Since It’s a Census Year – What better way to launch 2020 than with an article on this important decennial event. You might be expecting a rather dry recitation of data gathered by the United States government, dating back to the first one conducted in 1790. You would be wrong! I’ve seen the data and accompanying documentation which the government used, and heaven knows only they must understand exactly what it meant!

Census data is vital to genealogical research, yet it’s more than just tick marks (up until the 1850 census), name, age, marital status, occupation and so on. There are literally thousands (more like MILLIONS) of stories to be gleaned – not that I will attempt that feat here, however. This extensive article will look at each decennial census beginning with the first in 1790, through the 1940 census.

Mining the 1880 Census Mother Lode – Family Search refers to the 1880 census as the “mother lode of questions pertaining to physical condition, criminal status, and poverty.” Talk about stories! It took the better part of the 1880s decade to process, but was it ever worth it, all courtesy of the “Supplemental Schedules for Defective, Dependent, and Delinquent Classes” (sometimes referred to simply as the “Defective Schedules”).

Up in Smoke: 1890 and Genealogy’s “Black Hole” (or is it?) – Put on your thinking caps. What event which took place ninety-nine years ago has since become an ever-present challenging obstacle to genealogists? On January 10, 1921 most of the 1890 census went up in smoke – “most” being the operative word. A March 1896 fire had already destroyed a number of these records.

Anyone who has been researching for any length of time likely realizes finding one’s ancestors involves trying many “keys” to unlock hidden caches of records, photos, and so on. Genealogists love census records because they are fairly easy to both access and assess, making the missing 1890 census a discouraging “black hole” for some who haven’t yet tried a little creativity. Why guess (or fudge) when you can do a little extra digging and maybe find a really interesting story! This article is filled with information about this genealogical “black hole” and how to find substitute records utilizing some “research adventure” stories.

The So-Called Calendar Riots and Modern-Day Genealogical Research – Most of us don’t think about time and its measurement in terms of historical context. It’s just time – something we never seem to have enough of in our “gotta-have-it-now” world. Twice each year our internal time clocks (for the majority of Americans) are re-set because we observe what is called “Daylight Savings Time”. We “lose” an hour of sleep in the Spring, only to “gain” it back in the Fall – “spring forward” and “fall back”. World travelers jet around the world every day, losing a day or gaining one by crossing the International Date Line.

We typically grumble about the loss of zzz’s but our bodies (eventually) adapt fairly well. We certainly aren’t particularly exercised over the loss are we? An hour here, or even a day, is not of much concern. But what if it were eleven days? In the mid-eighteenth century a stir rippled throughout England (although less so in its American colonies) as Parliament enacted calendar reforms in 1751. This calendar-altering event affects genealogical research to this day, yet not as dramatically as it seems to have stirred up the rural populace of England at the time – or perhaps we should say as much as political satirists of the time made of the change and (supposed) uproar.

It all seems to involve a bit of revisionist history. In 21st century vernacular let’s call it “fake news”. While researching this article which was to focus on the differences between the Julian and Gregorian calendar systems (sometimes called, respectively, “Old Style” and “New Style”) and how it affects genealogical research, I came across the phrase: “Give us our eleven days!”

Subsequent references to the phrase implied there had been “calendar riots” circa 1752 when England decided to join the rest of continental Europe and adopt the Gregorian calendar which had been around since the 1580s. Attempts to locate the phrase “give us our eleven days” or “give us back our eleven days” in the eighteenth century yielded a big goose egg, although simply using “eleven days” yielded a few references in both England and America around the time of the calendar shift. . . Plus, the story of “setting standard time” in the late nineteenth century (to avoid “fifty-three kinds of time”).

What in the Blue Blazes . . . happened to my ancestor’s (fill-in-the-blank) record? – Family Tree Magazine (May/June 2018) called them “Holes in History” – destructive fires throughout United States history with far-reaching effects on modern-day genealogical research. It might have been the deed to your third great-grandfather’s land in Mississippi, your grandfather’s World War II service record, or the missing 1890 census records. This article will take a look at the stories behind these devastating events and provide tips for finding substitutes.

Here’s something we can all agree on: nineteenth and early twentieth century courthouse fires are the bane of genealogists everywhere. Have you ever wondered why so many courthouse fires occurred in the latter half of the nineteenth century? Would it surprise you to find that many of them were set nefariously? (It shouldn’t.)

Getting Knocked Up (a Queer English Custom) – Once upon a time everyday working folks paid someone to “knock them up”. This, of course, elicits winks and giggles amongst 21st century denizens as “knocked up” often refers to what Merriam-Webster calls “sometimes vulgar: to make pregnant”. There was nothing vulgar intended or implied as this quaint and curious English and Irish custom, begun during the Industrial Revolution and carried forward into the early twentieth century (and beyond for some locales), was an honorable occupation. Before alarm clocks were available and affordable, “getting knocked up” was essential to ensure working men and women avoided fines for arriving late to work.

OK, I Give Up . . . What is It? (Did my ancestors ever violate intercourse(!) laws?) – First, I write an article about getting “knocked up” and now “intercourse laws”. Ahem. Lest anyone think I’m referring to the world’s oldest profession, let me explain. I run across many interesting phrases and curious terms while researching family history for my clients or research for the magazine. One phrase popped up recently and curiosity got the best of me (as it so often does!).

True Grit: Heck Thomas and Sam Sixkiller – This is a companion article to “Did my ancestors ever violate intercourse laws? The short answer — yes, if your ancestor lived near or among Indians they may have at one time or another “violated intercourse laws”. These two legendary “bad-ass” lawmen were kept plenty busy in Indian Territory back in the day.

Family History Tool Box, May I Recommend (Book Reviews) and more!

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Tombstone Tuesday: Bigger Head (1812-1912)

Bigger Head was born in Highland County, Ohio on October 12, 1812 to parents William and Mary (Elder) Head. According to the Head family genealogy, William and Mary were cousins and together they had fourteen children, with ten of them living to adulthood. Bigger was the second son named Bigger – the first died at the age of eight months in 1807.

Bigger Head was born in Highland County, Ohio on October 12, 1812 to parents William and Mary (Elder) Head. According to the Head family genealogy, William and Mary were cousins and together they had fourteen children, with ten of them living to adulthood. Bigger was the second son named Bigger – the first died at the age of eight months in 1807.

I came across this family while researching a friend’s Head family line. I found multiple instances of the “Bigger” forename or middle name. First of all, I’ve never heard of anyone with the first name of “Bigger” so that alone was intriguing. Where did that come from?

I came across this family while researching a friend’s Head family line. I found multiple instances of the “Bigger” forename or middle name. First of all, I’ve never heard of anyone with the first name of “Bigger” so that alone was intriguing. Where did that come from?

This article has been removed from the free side of the site. It has been significantly updated with new research and featured in the March-April 2019 issue of Digging History Magazine. Purchase the issue here or contact me to purchase a copy of the article only.

Surname Saturday: Doe

Doe

The Doe surname is believed to have been of ancient Norman origins, presumably arriving in England as a result of the Norman Conquest of 1066. One family historian hypothesized that the surname was perhaps of Danish origin since the Danes frequently made incursions into Normandy. One source indicates the surname is derived from the old English word “da’” which was a nickname for a gentle man.

Many surnames have origins as place names as well and in the case of Doe could have been recorded as “D’Eu” or “D’O”. The Doe family, originally from the Castle of O and who came to England after the conquest, settled in Somerset. The surname could easily be derived from the place name “D’O”.

Some early records of Doe (or variations):

Edward Da of Lancashire (1185)

Robert Doe or Yorkshire (1273)

John de Do of Somerset (1327-1377)

Roger Doe of Yorkshire (1379)

Walter Do of Devon (1400)

Charles Doe was Lord High Sheriff of London (1635)

Joshua Doe or Ireland (1702-1703)

Benjamin Doe married Jane Shackledge in 1740 (London)

Some historians believe that “Dow” is an alternate spelling for this surname, but it is more likely of Scottish origin. Other sources claim that “Dewe” was an alternate spelling which I presume they believe morphed into “Doe” at some point. I say presume because most references to “Doe” when referring to those who came to America (Virginia) as “Dewe” have “(sic)” after “Doe”, e.g., Thomas Doe (sic) – it’s a little confusing! But, then again, nothing is easy when it comes to genealogy research!

Some historians believe that “Dow” is an alternate spelling for this surname, but it is more likely of Scottish origin. Other sources claim that “Dewe” was an alternate spelling which I presume they believe morphed into “Doe” at some point. I say presume because most references to “Doe” when referring to those who came to America (Virginia) as “Dewe” have “(sic)” after “Doe”, e.g., Thomas Doe (sic) – it’s a little confusing! But, then again, nothing is easy when it comes to genealogy research!

Several Does landed in Virginia as early as 1635. The first Doe immigrant in New England was Nicholas who had two sons named John and Sampson. The narratives below are based on the research of Elmer Doe who compiled and published The Descendants of Nicholas Doe (DND) in 1918.

Nicholas Doe

It is believed that Nicholas Doe was born in approximately 1631 in England. At the time DND was published, the author had been unable to determine exactly when or where Nicholas was born. A member of the Doe family, ninety years of age at the time, believed his grandfather had told him that Nicholas came from London. He had also been told that Nicholas’ father owned a whole street called “Blue Street” because all of the houses were blue.

Since there don’t appear to be any records of when Nicholas actually left England, Elmer Doe proposed the following:

A record was kept of those families who left England, and before leaving they were requested to take the oath of loyalty to the English Crown and promise conformity to the Established Church. As many desired to avoid this enforced allegiance and to settle in the land of their adoption free to follow their own religious inclinations, a great many of them left secretly and made their way as sailors, etc. It is possible that Nicholas Doe left England in this manner.

His name first begins to appear in New England records in 1666. From 1666 to 1672 he was taxed at Oyster River and on November 15, 1666 he witnessed the will of Thomas Walford at Portsmouth, New Hampshire.

As an early settler of Dover, New Hampshire, Nicholas was “received an inhabitant” on July 21, 1668 (Oyster River was a part of Dover at that time). The New England Historical and Genealogical Register, Volume VI, also records that Nicholas had a “difference” with John Goddard which was settled in 1674.

Another uncertainty is the date of Nicholas’ marriage to Martha Thomas. I think perhaps they were married in 1668, possibly around the time he was received as an inhabitant of Dover. Their first child, John, was born on August 25, 1669.

Records indicate that their second child Sampson was born on April 1, 1670, which to me seems a bit soon after John’s birth. Their third child and only daughter, Elizabeth, was born on February 7, 1673. Nicholas’ will referred to Sampson purchasing his sister Mary’s share of the estate. There may have been a fourth child named Mary, but records for Nicholas are rather sketchy. Nicholas died in Oyster River in 1691.

John Doe

Nicholas’ first child John married Elizabeth (surname unknown) and had seven children: Daniel, John, Joseph, Benjamin, Mary, Elizabeth and Martha. It appears, according to church records, that the whole family was baptized in November of 1719 and admitted to the Durham church. Reverend Hugh Adams baptized the children and referred to them all, except Martha (3 years old), as adults. Notably, Joseph who was born in 1707 lived to the age of 102 years.

John Doe died on April 28, 1742. Curiously, John’s sons and wife who were Subscribers to his will were listed as Elizabeth Doe (wife), Daniel Doe, John Doo, Joseph Doo and Benjamin Doo – not sure why the spelling is different for three of his sons.

Sampson Doe

Sampson married Temperance (surname unknown), perhaps in 1700. Children born to Sampson and Temperance were: Samuel (1701), Martha (1704), Nicholas (1707) and Temperance (1710).

Sampson married his second wife, Mary Ayers who was the widow of William Ayers of Portsmouth, on October 16, 1716. Children born to Sampson and Mary were: Nathaniel (1718), Mary (1720), Elizabeth (1722), Zebulon (1724) and Sarah (1727).

During the Indian War of 1712, Sampson served as a scout for Captain James Davis. Both Sampson and his brother John signed a petition to incorporate Oyster River. Apparently the area had grown enough to sustain itself and it was too inconvenient to travel to Dover to handle business affairs or to attend church:

[W]hereas now ye Petitioners have by divine providence settled and Inhabited that Part in this his Majests Provence commonly called Oyster River, and have found that be the scituation of the place as to Distance from Dover or Exeter butt more Especially Dover, how being forced to wander through the Woods to ye place to meet to and for ye management of our affairs are much Disadvantaged for ye Present in our Business and Estates and hindred of adding a Town and People for the Honr of his Majesty in the Inlargement and Increas of his Province. Wee humbly Supplicate that yor Honrs would take itt to yor Consideration and grant that we may have a Township confirmed by our honours….

When Oyster River was incorporated and a church established, Sampson was one of the church’s founding members. Sampson Doe died in 1748, his will dated April 14. He distributed to his remaining eight children (Temperance died in 1719) each three shillings. The remainder of his estate, including all his goods and chattels, was given to Mary who was also the Executrix of the will.

Sampson’s sons Nathaniel and Nicholas served in the French and Indian War and some of his grandsons served in the Revolutionary War. Although many of Sampson and John’s descendants remained in New Hampshire, by the fifth generation several began to migrate to Maine, New York and Massachusetts. In 1920 the greatest concentration of Does was still located in those states. It appears John was the most common forename paired with the Doe surname.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Feudin’ and Fightin’ Friday: County Seat Wars

A town’s designation as the county seat often determined whether it would thrive or fade away into history. Some county seat disputes turned into outright wars, bloodshed and all. Others, although politically charged and volatile, were more amicably (or sneakily) resolved. Here are a few of them, some “mild” and some “wild”:

A town’s designation as the county seat often determined whether it would thrive or fade away into history. Some county seat disputes turned into outright wars, bloodshed and all. Others, although politically charged and volatile, were more amicably (or sneakily) resolved. Here are a few of them, some “mild” and some “wild”:

Baldwin County, Alabama

Baldwin County, Alabama was established in December of 1809, named after Senator Abraham Baldwin, a man who actually never set foot in the county. He was a native of Guilford, Connecticut and involved in the founding of the United States Constitution. After graduating from Yale he moved to Georgia to practice law and was later elected to the Georgia State Legislature. Many of the county’s settlers had migrated from Georgia and they suggested the name to honor Baldwin’s accomplishments.

According to the County’s web site, an “undercover scheme” was hatched which would determine the town designated as county seat. The first county seat was a town by the name of McIntosh Bluff, but when it became part of another county, the seat was moved to Daphne in 1868. In 1900 the Alabama Legislature designated a change to make Bay Minette the county seat. The residents of Daphne resisted that move, however.

According to the County’s web site, an “undercover scheme” was hatched which would determine the town designated as county seat. The first county seat was a town by the name of McIntosh Bluff, but when it became part of another county, the seat was moved to Daphne in 1868. In 1900 the Alabama Legislature designated a change to make Bay Minette the county seat. The residents of Daphne resisted that move, however.

Some residents of Bay Minette devised a scheme to draw the sheriff and his deputies out of Daphne by fabricating a murder. While the lawmen were out chasing a phantom criminal, the men who devised the ruse traveled to Daphne, stole the county records and delivered them to Bay Minette. Bay Minette has been the county seat of Baldwin County ever since.

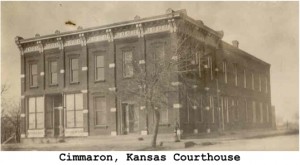

Gray County, Kansas

Gray County, Kansas was founded on March 13, 1881 and named after a Kansas politician, Alfred Gray, who had died the year before of tuberculosis. The town of Cimarron, located on the Santa Fe Trail, served as the first county seat. In 1887 three towns vied for the county seat designation: Cimarron, Ingalls and Montezuma.

A few years before, Asa T. Soule had come to the area to invest in a venture proposed by two brothers which would form a vast irrigation system by diverting water from the Arkansas River. Soule was a Rochester, New York millionaire who had made his fortune mostly in the lucrative patent medicine business. Like the majority of medicines peddled as cure-alls in that era, Soule’s Hop Bitters consisted mostly of alcohol.

When Soule came to Kansas he inserted himself into area politics and founded the town of Ingalls. To ensure that Ingalls would be the county seat, he promised to build a railroad from Dodge City to Montezuma which would continue on to the coal fields of Trinidad, Colorado (all free of cost), if only Montezuma would withdraw from the county seat race. When it became apparent that even his promise of a railroad wouldn’t garner him enough county votes Soule tried bribery, dispensing money freely ($100-$500) to residents of Montezuma.

To further advance their schemes, an agent of Soule’s, George Gilbert from Dodge City, came to Cimarron with a group of “enforcers” headed by none other than Bat Masterson. With “long guns and short guns” they camped out at a Cimarron hotel, continuing to dispense monetary bribes to voters on election day October 31, 1887. One witness would later testify that over five thousand dollars was dispensed that day.

Despite those nefarious efforts, however, Cimarron won the county seat race by a forty-one vote majority. According to the Hutchinson News:

The only thing for our citizens to do was to arm ourselves, which they did as well as they could, and protected the polls, preventing the capture of the ballot box, polling lists, etc., and the killing of the election board, for which the gang were to get ten thousand dollars. Nothing but the unfailing courage of our citizens, who had at stake life, property and all that was dear to them, prevented the gang from carrying out the nefarious scheme.

While ballots were being counted, a fire was started, burning down an entire city block of buildings. Cimarron residents suspected the fire was intentional, “set by [their] enemies”. Even though the ballot count favored Cimarron, Ingalls claimed a two hundred vote majority.

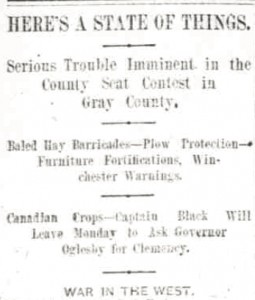

The Wichita Daily Eagle warned of trouble following the election, declaring “War in the West”:

The citizens of Cimarron continued to be harassed by Soule, Gilbert and their cohorts. An attorney, George Dunn, came from Missouri and settled in Cimarron just before the election. In reality he was a “hireling” of Soule and Gilbert. Ingalls placed Dunn on the ballot for county attorney, which he won with the backing of Soule and Gilbert money.

In November, Ingalls challenged the validity of the election, asserting that the election officers who counted the votes would not be officially placed in office until the following January. Dunn, the new county attorney, asked the district court to compel the county officers to move their offices to Ingalls, with which the court agreed. The case became further entangled when the Kansas Supreme Court was called upon to settle the dispute in 1888. However, the Supreme Court declined to rule otherwise and agreed with the district court.

The dispute escalated in early 1889. The county offices, except county clerk and surveyor, had been housed in Ingalls for over a year. When an Ingalls candidate one the election for county clerk, the records were to be moved from Cimarron to Ingalls. On January 12, as deputy sheriffs were loading the records for transfer, a mob of approximately two hundred Cimarron citizens came and began firing upon the deputies. Two were killed and three slightly wounded. The mob captured the county clerk and four of the deputies and held them in the courthouse, until officers from Dodge City came to assist and arranged their release.

The Cimarron vowed revenge, threatening to burn down the town of Ingalls and kill all its citizens. The governor sent the Kansas militia to intervene and by January 14, the newspapers were reporting that Ingalls had been placed under martial law and was quiet.

The Cimarron vowed revenge, threatening to burn down the town of Ingalls and kill all its citizens. The governor sent the Kansas militia to intervene and by January 14, the newspapers were reporting that Ingalls had been placed under martial law and was quiet.

The dispute would go on for quite a while longer, however. The back and forth of politics, heated arguments, bribery, chicanery and mob force resulting in bloodshed, was finally settled a special election held in February of 1893 when Cimarron was finally designated as the permanent county seat of Gray County.

Postscript: The original irrigation scheme which brought A.T. Soule to Kansas turned out to be a bust, becoming known as Soule’s Folly.

Castro County, Texas

The area now known as Castro County, Texas was occupied by Comanches, who had forced out the Apaches in 1720, until the Red River War of 1874 forced them onto reservations. Castro County was established by the Texas Legislature in 1876 and in the early 1880’s the Carters, a ranching family, arrived. Still, by 1890 the county’s population was still miniscule. On March 4, 1890 the Bedford Town and Land Development Company was formed by H.G. Bedford, a resident of Grayson County. On May 27, the company bought a section of land near the county’s center and began to lay out the town, digging a well and building a water tower. One of the partners, Reverend W.C. Dimmitt, was a close friend of Bedford’s and the town was named in his honor.

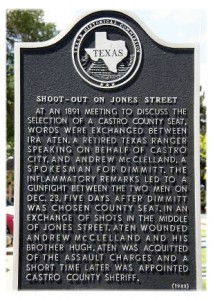

By 1891 the need for local government became more pressing with more settlers coming to the county. Other town sites had sprung up in the county and Castro City and Dimmitt would be the leading candidates for county seat. Two men met on the courthouse lawn in Dimmitt on December 23, 1891. Ira Aten was a retired Texas Ranger representing the interests of Castro City, and Andrew McClelland was a spokesman for Dimmitt.

By 1891 the need for local government became more pressing with more settlers coming to the county. Other town sites had sprung up in the county and Castro City and Dimmitt would be the leading candidates for county seat. Two men met on the courthouse lawn in Dimmitt on December 23, 1891. Ira Aten was a retired Texas Ranger representing the interests of Castro City, and Andrew McClelland was a spokesman for Dimmitt.

Heated remarks led to a gunfight between the two, with Aten wounding Andrew McClelland and his brother Hugh (they recovered). Five days later Dimmitt won the county seat. Aten was later acquitted of assault charges and shortly thereafter was appointed as Castro County Sheriff.

These county seat disputes were mild by comparison to others like the one in Stevens County, Kansas, the bloodiest county seat war in the West, and one in Wichita County (a future Feudin’ and Fightin’ article I’m sure).

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Wild West Wednesday: “Wholesale Murder at Newton”

It’s been called “The Gunfight at Hyde Park” or the “Newton Massacre”. The Emporia News (Kansas) headlined it as “Wholesale Murder at Newton”, the White Cloud Kansas Chief called it an “affray” and the Lawrence Daily Journal called it a “riot”. Whatever, it was bloody, and one of the biggest gunfights in the history of the Wild West – more were killed than the Gunfight at the OK Corral.

It’s been called “The Gunfight at Hyde Park” or the “Newton Massacre”. The Emporia News (Kansas) headlined it as “Wholesale Murder at Newton”, the White Cloud Kansas Chief called it an “affray” and the Lawrence Daily Journal called it a “riot”. Whatever, it was bloody, and one of the biggest gunfights in the history of the Wild West – more were killed than the Gunfight at the OK Corral.

In 1871, the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad had extended its line past Abilene, Kansas and established a terminal at Newton. In a pattern repeated numerous times during that era throughout the West – discover gold or silver or put in a railroad line, and towns would quickly go from bucolic to rambunctious.

Up until that time, Texas cattle had been brought to Abilene for shipping, but after the rail line extension Newton became “cowboy central”. Of course, when cowboys came to town they wanted to be entertained – places like the Do Drop Inn, Side Track and the Gold Room, twenty-seven saloons and eight gambling halls in all. The trains arrived on July 17, 1871 and trouble followed soon after.

Up until that time, Texas cattle had been brought to Abilene for shipping, but after the rail line extension Newton became “cowboy central”. Of course, when cowboys came to town they wanted to be entertained – places like the Do Drop Inn, Side Track and the Gold Room, twenty-seven saloons and eight gambling halls in all. The trains arrived on July 17, 1871 and trouble followed soon after.

Did you enjoy this article snippet? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. This article has been refreshed with new research and published in the July-August 2019 issue of the magazine. The magazine is on sale in the Digging History Magazine store and features these stories (100+ pages of stories, no ads):

Did you enjoy this article snippet? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. This article has been refreshed with new research and published in the July-August 2019 issue of the magazine. The magazine is on sale in the Digging History Magazine store and features these stories (100+ pages of stories, no ads):

- “Drought-Locusts-Earthquakes-B-Blizzards (Oh My!)” – Perhaps no state is possessive of a more appropriate motto than Kansas: Ad Astra per Aspera (“To the stars through difficulties”, or more loosely translated “a rough road leads to the stars”1). By the time the state adopted its motto in 1876, fifteen years post-statehood, it had experienced not only a brutal, bloody beginning (“Bloody Kansas”) but had endured (and continued to struggle with) extreme pestilence, preceded by severe drought and even an earthquake in April 1867. In the early days being Kansan was not for the faint of heart.

- “Home Sweet Soddie” – For years The Great Plains had been a vast expanse to be endured on the way to California and Oregon. Now the United States government was making 270 million acres available for settlement – practically free if, after five years, all criteria had been met. The criteria, referred to as “proving up” meant improvements must be made (and proof provided) by cultivating the land and building a home. For many their first home would be a dugout, a sod-covered hole in the ground.

- “Wholesale Murder at Newton” – It’s called “The Gunfight at Hyde Park” or the “Newton Massacre”. One newspaper headlined it as “Wholesale Murder at Newton”, another called it an “affray” and another a “riot”. Whatever, it was bloody, and one of the biggest gunfights in the history of the Wild West, more deadly than the legendary gunfight at the OK Corral.

- “Kansas Ghost Towns” – It might be more appropriate to call this Kansas ghost town, established by Ernest Valeton de Boissière in 1869, a “ghost commune” (Silkville). Nicodemus. There was something genuinely African in the very name. White folks would have called their place by one of the romantic names which stud the map of the United States, Smithville, Centreville, Jonesborough; but these colored people wanted something high-sounding and biblical, and so hit on Nicodemus.

- “The Land of Odds: Kwirky Kansas” – For some of us the mention of Kansas invokes memories of one of the classic films of our childhood, The Wizard of Oz. With a tongue-in-cheek reference this article highlights some of the state’s history and people in a series of vignettes – some serious, some not so serious (the real “oddballs”) in a light-hearted fashion. A rollicking fun article covering a range of Kansas “oddities” and “oddballs”, including one of the most dangerous quacks to have ever practiced medicine, Dr. John R. Brinkley.

- “Mining Kansas Genealogical Gold” – One of my favorite “adventures in research” is to discover obscure genealogical records or perhaps stumble across a set of records at Ancesty.com or Fold3 which turns out to be a gold mine of information. This article highlights some real gems available at Ancestry.

- “Chautauqua: The Poor Man’s Educational Opportunity” – During an era spanning the mid-1870s through the early twentieth century, Kansans, like many Americans across the country, anticipated the summer season known as Chautauqua, an event Theodore Roosevelt called “the most American thing in America”. By 1906 when Roosevelt made such an astute observation the movement had evolved into a non-sectarian gathering, where “all human faiths in God are respected. The brotherhood of man recreating and seeking the truth in the broad sunlight of love, social co-operation.”

- And more, including book reviews and tips for finding elusive genealogical records.

Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Surname Saturday: Starbuck

The surname Starbuck is believed to have Scandinavian origins. Norsemen (Vikings) came down to Scotland and Ireland between 800 and 1100 A.D. to plunder and terrorize. After a time these Vikings intermarried with women of the villages and later plundered along the coast of England.

According to Alexander Starbuck’s History of Nantucket, “the name Starbuck is Scandinavian and signifies a person of imposing appearance, great or grand bearing.” In the Patronomyca Britannica there is a Norse name which is pronounced “Stor bokki”. “Stor” means great (body, soul and spirit) and “bokki” means great man (one with higher status and ranking). The spelling variations for this surname include “Starbocki”, “Starbock”, “Stirbock,” “Stalbrook”, “Sturbock”, “Styrbuck”, just to name a few. One family historian suggested that “Starbuck” was finally settled upon because it was easier to pronounce: “Stah’buck”.

I’ve been doing genealogical research for a friend and ran across this surname. The history is fascinating, including some who came to America and were persecuted by the Puritans because they were Anabaptists (see my recent article here for more on this subject) and some who converted to Quakerism (Quakers were also persecuted by the Puritans).

Edward Starbuck

Edward Starbuck was born in Derbyshire or Attenborough, England in 1604. He married Katherine Reynolds and came to New England around 1635. He arrived in Dover, Massachusetts (now New Hampshire) and became a prominent member of that town. His name can be found multiple times in New Hampshire court records, as well as histories of Nantucket Island.

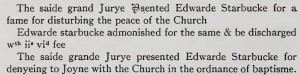

In 1648, Edward appeared before the court grand jury and received a fine for “disturbing the peace of the Church” and “denyeing to Joyne with the Church in the ordnance of baptisme.”

Along with Christopher Lawson who was guilty of stealing a bottle of wine from a neighbor’s cellar, Thomas Williams “for a fame of committing fornication with Judith Ellyns of strawberey banke” and John Batten for “beinge disteinged with drinke & for fighting & quarreling upon the lords daye”, Edward Starbuck was punished for his religious beliefs.

Notwithstanding his religious beliefs and the persecution he suffered, it appears that Edward was a highly respected citizen of Dover. In 1643 he was elected the first General Representative from Dover to the General Court of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, and again in 1647.

Edward and Katherine had six children: Nathaniel, Sarah, Dorcas, Abigail, Esther and Jethro. Jethro died at the age of twelve, so Nathaniel was the only son to carry the Starbuck line forward. In the summer of 1659, Edward accompanied Tristram Coffin and Isaac Coleman for a visit to the islands off the coast of Massachusetts.

Nantucket Island had been discovered in 1602 by Bartholomew Gosnold and claimed by England as part of the colonies. Thomas Mayhew purchased the island in 1641 for forty pounds, using the land to graze his sheep. He and Peter Folger were also able to convert some of the Indians to Christianity. The island was sold to nine men: Tristram Coffin, Richard Swain, Peter Coffin, Stephen Greenleaf, William Pike, Thomas Macy, Thomas Barnard, Christopher Hussey and John Swain. Edward and his son Edward were chosen as associates and became part of the ownership of the island. In 1671, Edward and his son Nathaniel participated in negotiations with the Indians in purchasing more land.

While some have hypothesized that Edward migrated to Nantucket because of religious persecution, it’s just as likely he moved there to pursue business interests. In October of 1659, at the age of 55, Edward accompanied Thomas Macy to Nantucket where they spent the winter. In the spring of 1660 he returned to Dover and brought his family, except daughters Sarah (Austin) and Abigail (Coffin) who had married and settled in Dover, to the island. As in Dover, Edward was a well-respected citizen of the island. He returned to the mainland at least one more time to bring other families to the island.

Edward Starbuck died in 1690 on Nantucket Island. His son Nathaniel was the beneficiary of most of Edward’s property.

Nathaniel Starbuck

Nathaniel was the only surviving son of Edward and Katherine Starbuck. Thus, he is the ancestor of all American Starbucks. Nathaniel was born in either 1635 or 1636 and where he was born likely depends on exactly when Edward and Katherine arrived in Dover. Other than accompanying his parents to Nantucket, not much is known about his early life. He married Mary Coffin, daughter of Tristram Coffin, in 1662 and they had ten children, two of them dying in their youth. Their first child, Mary, was the first English baby born on Nantucket Island.

Nathaniel did quite well for himself and increased his business holdings and land after being the beneficiary of Edward’s possessions. He and Mary ran a store which sold items such as molasses, rope, powder, rum and beer. It appears that Mary was a shrewd businesswoman, keeping a detailed account book. Her account book emphasized the potential “benefits of the English economic system” to the Indians who lived on the island.

In 1699, Nathaniel built a home which came to be known as the Parliament House. Sometime in the early 1700’s, Quaker missionaries arrived on the island and Mary became interested in their faith. Mary’s opinions and advice apparently carried a lot of weight on the island. According to The Coffin Family: The Life of Tristram Coffyn:

In 1699, Nathaniel built a home which came to be known as the Parliament House. Sometime in the early 1700’s, Quaker missionaries arrived on the island and Mary became interested in their faith. Mary’s opinions and advice apparently carried a lot of weight on the island. According to The Coffin Family: The Life of Tristram Coffyn:

She was consulted on all matters of public importance, because her judgment was superior, and she was universally acknowledged to be a great woman. It was not that her husband, Nathaniel Starbuck, was a man of inferior mould, that she gained such prominence, for he was a man of good ability; but because of her pre-eminent qualifications that she acquired so good a reputation, whereby her husband’s qualifications were apparently lessened.

John Richardson, a minister, said about her, “[T]he islanders esteemed her as a Judge among them, for little of moment was done without her.” When she became interested in the Quaker faith in 1701, she subsequently took on a significant spiritual leadership role.

Nathaniel and Mary opened their home to the Friends where their meetings were held beginning in 1708 when the Nantucket Meeting was established. Mary wrote the quarterly epistles and also preached. She served as an elder and her son Nathaniel, Jr. served as clerk. John Richardson wrote of Mary that “she submitted to the Power of Truth and the Doctrines thereof and lifted up her Voice and wept.” On that day two hundred people attended the meeting and many were converted.

Mary died on November 13, 1717 and Nathaniel died on February 2, 1719 (although one account lists his death on August 6 of that year). They are buried in the Friends Cemetery, although there are very few headstones – apparently Quakers disapproved of them, considering them idolatrous.

Later, some of the Starbucks became whalers. Interestingly, one of Herman Melville’s Moby Dick characters was a chief mate named Starbuck, a Quaker.

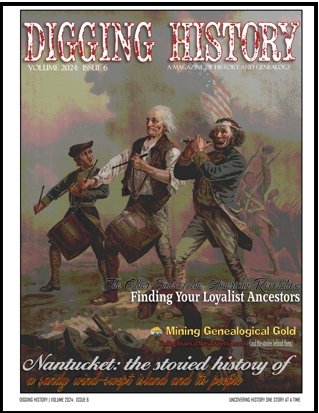

For an extensive article on Nantucket Island and its settlers, including the Starbuck, Macy and Coffin families, see this 2024 issue featuring Massachusetts (Part 2 of a two-part series).

For an extensive article on Nantucket Island and its settlers, including the Starbuck, Macy and Coffin families, see this 2024 issue featuring Massachusetts (Part 2 of a two-part series).

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Feisty Females: Cornelia Clark Fort

Cornelia Clark Fort was born February 5, 1919 in Nashville, Tennessee to parents Rufus Elijah and Louise Clark Fort. Her father was a successful physician and businessman who had already made his fortune long before Cornelia was born. In 1909 he married Louise Clark and together they raised their family at Fortland, a sprawling 365-acre estate.

Cornelia Clark Fort was born February 5, 1919 in Nashville, Tennessee to parents Rufus Elijah and Louise Clark Fort. Her father was a successful physician and businessman who had already made his fortune long before Cornelia was born. In 1909 he married Louise Clark and together they raised their family at Fortland, a sprawling 365-acre estate.

Although the family was wealthy, Cornelia’s father made sure his children weren’t “spoiled rich kids”, insisting that they attend public school in order “to know people and learn to get along with everybody,” her brother Dudley said. In school, Cornelia excelled in her favorite subjects of history, literature and English and loved to read – math and science she barely passed. The family chauffeur, Epperson Bond, schooled her in Latin as he drove her to school (her father never learned to drive).

By the time she was thirteen years old, Cornelia was 5 feet, 10 inches tall which made social situations a bit awkward for her – she towered over her peers, male and female. Neither did she inherit her mother’s social finesse and grace, being more fun-loving and carefree. Cornelia was enrolled in a finishing school in seventh grade, but she managed to cultivate her own circle of friends, eschewing the more popular sororities.

By the time she was thirteen years old, Cornelia was 5 feet, 10 inches tall which made social situations a bit awkward for her – she towered over her peers, male and female. Neither did she inherit her mother’s social finesse and grace, being more fun-loving and carefree. Cornelia was enrolled in a finishing school in seventh grade, but she managed to cultivate her own circle of friends, eschewing the more popular sororities.

Her parents insisted on a very strict Southern upbringing. When Cornelia, age seventeen, wanted to join her girlfriends for a trip to Europe, her father sternly refused. Upon graduating high school, however, she began to exercise more individual freedom. She spent one year at a junior college in Philadelphia and then on to Sarah Lawrence, an all-female college. There she excelled and flourished – a friend would later remark that “she became self-confident because she was successful and happy at Sarah Lawrence.”

As with most young ladies from wealthy Southern families, Cornelia made her official debut into Nashville society on December 29, 1939 while home on Christmas break during her senior year at Sarah Lawrence, perhaps reluctantly, according to her family. Southern women, after graduation, were expected to do all the “right things” like join the Junior League and other elite societies, all of which Cornelia did. Then she discovered flying.

Her friend Betty Rye was dating Jack Caldwell who was part-owner of a flying service. Cornelia had wanted to find out what it was like to fly and whether she would like it. After one flight, she was hooked. Caldwell remarked, “she just ate it up like it was jelly or something. She got up and didn’t want to go back.” Betty and Cornelia began their first lesson together, but Cornelia was the one who wanted more – Betty was finished with flying after one lesson.

Her father died on March 21, 1940 and one month later she flew her first solo flight. Given how stern her father was, her father might not have been comfortable with her choices. She was exhilarated after her first solo flight, but her mother was said to have been less than thrilled, remarking, “how very nice, dear. Now you won’t have to do that again.” Of course, given her enthusiasm and rebellious streak, Cornelia was not deterred – by June she had her private pilot’s license.

With license in hand, she could fly anywhere she wanted in the United States – the first week she flew two thousand miles! She soon graduated from flying a Piper Cub to a Waco UPF7 which was larger and more powerful. Upon completion of that training, she received her commercial pilot’s license which would allow her to instruct others. She became Tennessee’s first female flight instructor on March 10, 1941.

Even though the United States had not yet entered World War II, President Roosevelt kept a wary eye on Adolph Hitler’s mushrooming power, especially his air force. In response, the Civilian Pilots Training Program was established in 1940. One of the designated training sites was Massey Ransom Flying Service in Fort Collins, Colorado. You might guess that, of course, Cornelia applied for a job there and was hired.

Her mother again expressed her disapproval for her daughter’s pursuits, however. She was mortified that Cornelia planned to drive across the country from Nashville to Colorado alone. Epperson Bond, the family chauffeur, accompanied her instead.

During her training in Colorado she flew sixteen hours a day for six months. In October of 1941, she took a job in Honolulu, Hawaii teaching defense workers, soldiers and sailors. She loved her job. Writing to her mother she said, “[I]f I leave here I will leave the best job that I can have (unless the national emergency creates a still better one), a very pleasant atmosphere, a good salary, but far the best of all are the planes I fly. Big and fast and better suited for advanced flying.”

Two months after arriving in Hawaii she was an eyewitness to the horrors of Japan’s sudden attack on Pearl Harbor. Cornelia penned an eyewitness account which later appeared in the July 1943 issue of Woman’s Home Companion:

I knew I was going to join the Women’s Auxiliary Ferry Squadron before the organization was a reality, before it had a name, before it was anything but a radical idea in the minds of a few men who believed that woman could fly airplanes. But I never knew it so surely as I did in Honolulu on December 7, 1941.

At dawn that morning I drove from Waikiki to the John Rogers Civilian airport right next to Pearl Harbor, where I was a civilian pilot instructor. Shortly after six-thirty I began landing and take-off practice with my regular student. Coming in just before the last landing, I looked casually around and saw a military plane coming directly toward me. I jerked the controls away from my student and jammed the throttle wide open to pull above the oncoming plane. He passed so close under us that our celluloid windows rattled violently and I looked down to see what kind of plane it was.

The painted red balls on the tops of the wings shone brightly in the sun. I looked again with complete and utter disbelief. Honolulu was familiar with the emblem of the Rising Sun on passenger ships but not on airplanes.

I looked quickly at Pearl Harbor and my spine tingled when I saw billowing black smoke. Still I thought hollowly it might be some kind of coincidence or maneuvers, it might be, it must be. For surely, dear God.

Then I looked way up and saw the formations of silver bombers riding in. Something detached itself from an airplane and came glistening down. My eyes followed it down, down and even with knowledge pounding in my mind, my heart turned convulsively when the bomb exploded in the middle of the harbor. I knew the air was not the place for my little baby airplane and I set about landing as quickly as ever I could. A few seconds later a shadow passed over me and simultaneously pullets splattered all around me.

Suddenly that little wedge of sky above Hickham Field and Pearl Harbor was the busiest fullest piece of sky I ever saw.

We counted anxiously as our little civilian planes came flying home to roost. Two never came back. They were washed ashore weeks later on the windward side of the island, bullet-riddled. Not a pretty way for the brave little yellow Cubs and their pilots to go down to death.

After the attack, there was no more need for civilian pilots in Hawaii – reluctantly, she had to leave. The only way to fly after returning home was to go back to work for the Civilian Pilots Training program. In September 1942, the Women’s Auxiliary Ferrying Squadron (WAFS) was established. Cornelia received a telegram inviting her to report within twenty-four hours – she left immediately.

Mrs. Nancy Love had been appointed Senior Squadron Leader of the WAFS by the Secretary of War. Cornelia praised her qualifications, saying “[N]o better choice could have been made. First and most important she is a good pilot, has tremendous enthusiasm and belief in women pilots and did a wonderful job in helping us to be accepted on an equal status with men.”

Cornelia had no illusions about the challenges she faced as a female pilot in the service of her country. She knew at that time in history there was no hope of replacing male pilots. She was content to play her part by ferrying trainers or delivering planes to military bases. Cornelia was proud to serve her country and it brought her satisfaction like nothing else she had ever experienced.

On March 21, 1943, three years after her father’s death, Cornelia took off from San Diego along with seven other pilots (male and female) to deliver planes to Love Field in Dallas. A friend would later relate the events of that flight:

Some of [the male pilots[ began teasing [Cornelia] and then they began to pretend that they were fighter pilots. She was easy game for them, for she had never had any evasive training in military maneuvering. By the time they got to Texas, a few of the men has become too bold and were flying too close. A joke had become harassment.

One of the male pilots took his plane into a rolling dive, frightening Cornelia. She tried to evade him, but instead the two collided – his landing gear snapped off the top of her plane’s left wing and peeled it back six feet. Cornelia’s plane rolled, went into a dive and slammed into the ground. The plane did not catch fire, but the engine was buried two feet into the ground and Cornelia Fort had died. The crash occurred near Merkel, Texas.

Her squadron leader wrote to Cornelia’s mother: “My feeling about the loss of Cornelia is hard to put into words – I can only say that I miss her terribly, and loved her…If there can be any comforting thought, it is that she died as she wanted to – in an Army airplane, and in the service of her country.” Although Cornelia was not to blame for the crash, the program was never the same. The WAFS was disbanded in 1944 and members were not eligible for benefits. Belatedly, in 1977 Congress did finally declare they were indeed part of the military.

Her squadron leader wrote to Cornelia’s mother: “My feeling about the loss of Cornelia is hard to put into words – I can only say that I miss her terribly, and loved her…If there can be any comforting thought, it is that she died as she wanted to – in an Army airplane, and in the service of her country.” Although Cornelia was not to blame for the crash, the program was never the same. The WAFS was disbanded in 1944 and members were not eligible for benefits. Belatedly, in 1977 Congress did finally declare they were indeed part of the military.

Cornelia was only twenty-four years old when she died, a short life, but one well-lived. The final paragraph of the Woman’s Home Companion article (which was published after her death and perhaps penned a short time before her death), summed up her passion:

I, for one, am profoundly grateful that my one talent, my only knowledge, flying, happens to be of use to my country when it is needed. That’s all the luck I ever hope to have.

When I ran across Cornelia’s story, I realized that her story was the basis of an excellent book I had just read, The All Girls Filling Station’s Last Reunion, by Fannie Flagg. It’s a great book and you can probably find it at your local library or online at Amazon ($6.49 Kindle) or Barnes and Noble ($6.49 Nook).

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Wild West Wednesday: Elsa Jane Forest Guerin (a.k.a. Mountain Charley)

She was born under less than “normal” circumstances. Her birth mother had fallen in love with someone who promised to marry her upon his return from a trip to Kentucky. When his trip was extended, she despaired and thought that she had been betrayed. She settled for a “drunken, worthless vagabond” who was overseer of a neighboring plantation. But then her true love returned, and upon finding her married, promptly left for France. Some time later, her birth mother and her first love had an extramarital affair which resulted in Elsa’s birth. Elsa, however, was turned over to her mother’s brother to raise.

She was born under less than “normal” circumstances. Her birth mother had fallen in love with someone who promised to marry her upon his return from a trip to Kentucky. When his trip was extended, she despaired and thought that she had been betrayed. She settled for a “drunken, worthless vagabond” who was overseer of a neighboring plantation. But then her true love returned, and upon finding her married, promptly left for France. Some time later, her birth mother and her first love had an extramarital affair which resulted in Elsa’s birth. Elsa, however, was turned over to her mother’s brother to raise.

Elsa remembered that as a young girl she was adored by both her uncle and his negro servants, and often her mother, “Aunt Anna”, would visit. At the age of five, Elsa was sent to New Orleans to attend school, and only saw her uncle on occasion – they communicated mostly through letters and he always made sure she was well provided for.

At the age of twelve, something changed because Elsa, according to her autobiography, “developed with a rapidity marvelous even in the hotbed, the South, and upon reaching the age of twelve, I was as much a woman in form, stature and appearance as most women at sixteen.” She met a man who she thought handsome and they began to meet on the sly, since he was not allowed to visit her at the school. He won her heart and one morning she packed everything she could carry and made her escape through a window. Not long after she was, in her words, “standing before a clergyman and was united for better or worse, to him to whom I had given the first fruits of my affections.”

She soon learned that her new husband was a steamboat pilot on the Mississippi – something she had not thought to inquire about before her marriage. They had a pleasant honeymoon traveling through the South and after a month they settled in St. Louis. She settled into her new life as a wife, happy and content and not the least bit regretful of her decision. In her words, “My happiness was, if possible, made greater when at the end of about a year after my marriage, I found a breathing likness [sic] of my husband laid by my side. Three years after my marriage, another stranger came among us – this time a daughter.”

She soon learned that her new husband was a steamboat pilot on the Mississippi – something she had not thought to inquire about before her marriage. They had a pleasant honeymoon traveling through the South and after a month they settled in St. Louis. She settled into her new life as a wife, happy and content and not the least bit regretful of her decision. In her words, “My happiness was, if possible, made greater when at the end of about a year after my marriage, I found a breathing likness [sic] of my husband laid by my side. Three years after my marriage, another stranger came among us – this time a daughter.”

Life was good — what more could a woman ask for than a loving husband and two beautiful children. Tragedy struck, however, just three months after the birth of her daughter. One day while playing with her son a knock was heard at the door – the news was not good. Her husband had been shot, mortally wounded, by a fellow shipmate named Jamieson who was settling a grudge.

Still reeling from shock and grief, a few days later she received a letter informing her of Anna’s death. Anna’s last letter to Elsa was also enclosed and in it “she revealed to me the sad secret of my birth, but told it such loving words that it took away the sting of its illegitimacy.” Two blows in a short time, but one more shock was coming. She was soon informed by her attorney that her husband had spent money as he had earned it, never setting aside any for the future. Elsa was financially crippled, “completely a beggar”, in her words.

By this time, Elsa was probably only sixteen years old and faced with a seemingly insurmountable situation. She did not allow it to get her down, but instead began to develop a bitter hatred for the person who had made her a widow and a beggar – Jamieson! The more desperate her financial situation became the more hate she felt for the man. She searched for a way to get retribution for Jamieson’s crime against her husband and was eventually forced into pawning her possessions and taking a life-altering and drastic step.

She being so young had never learned any sort of trade and knew that her gender and age would be held against her, preventing her from supporting herself and her children. So, she determined to do something “so religiously closed against my sex” – she began to dress herself in male attire. She also thought it would give her better chance to carry out her desire to some day get revenge for her husband’s death.

Jamieson had been tried and convicted but had managed to escape punishment because of a legal technicality. She approached a friend of her late husband and asked for his help. Although he was reluctant to be involved in her plans to disguise herself as a male, he eventually relented when she convinced him it was her only means to avoid starvation. He purchased her a suit of boy’s clothes.

To put her plan into operation, Elsa turned her children over to the Sisters of Charity. She cut her hair to the normal length of a man’s, donned the suit and “endeavored by constant practice to accustom myself to its peculiarities and to feel perfectly at home.” She looked like a boy of fifteen or sixteen years old and a previous asthmatic condition which left her with a bit of hoarseness in her voice was a perfect way to complete her disguise. Elsa became Charley.

After several fruitless attempts to find employment, Charley finally found a job as a cabin boy on a steamer that ran between St. Louis and New Orleans. She would earn $35 per month, determined to endure a life as the “stronger sex”. Luckily, her job was menial in nature so that she could quietly attend to her work without drawing attention to herself. Once a month she would visit her children, first stopping at the friend’s house to change into a dress. It was difficult, but she remained on the boat for almost a year before she found another job as second pantryman. She changed jobs about every six months for a period of time. After she left her last river boat job, she became a brakeman for the Illinois Central Railroad in the spring of 1854.

She was still supporting her children and knew that if she reverted back to life as a woman she would never be able to support them in the manner she had become accustomed to in the four years since donning male attire. But then again, she liked the freedom that the male disguise gave her – she could go anywhere she chose – and “the change from the cumbersome, unhealthy attire of woman” was more suited to her.

While working for the railroad, her boss became suspicious of her gender and plotted to trick her into revealing her true identity. She overheard the plot and was able to escape, this time heading to Detroit. After a tour that took her to Niagra Falls and Canada she decided to return to St. Louis with and eye to eventually head to St. Joseph and westward. While in St. Louis she visited her children, but also ventured out in male attire to walk the streets of the city. One day she overheard a name – Jamieson. As she turned to look she contemplated whether to pull the trigger on the concealed revolver she carried. But then she thought really there was no need to hurry – he wasn’t going anywhere and if she acted it “would end the sweet anticipations of revenge which filled my soul.”

So she followed him to a gambling hall and watched him for hours. When he finally departed, Charley caught up to him and revealed her true identity to him. She pulled out her revolver and shot at Jamieson who immediately drew his gun and fired at her – neither was harmed. Jamieson fired again and Charley was hit in her thigh – she fired again and shot Jamieson in his left arm. The whole scene had lasted about five seconds and both managed to escape, although Charley passed out in an alley.

Upon awakening she found herself in a clinic, attended by a physician and an elderly woman. Her thigh was broken and required six months to completely heal. The elderly woman cared for Charley and her children came to visit. But when her recovery was complete she found her finances depleted and resumed her disguise. Gold fever had still not subsided and Charley joined a party of sixty men headed to California. Leaving her children was difficult, but she saw no other means to provide for them.

She made the long and arduous journey, keeping a journal as the group made their way across the vast prairies and mountains between Missouri and California. Upon reaching her destination, she found the job of gold miner unsuitable and instead found a job in a Sacramento saloon which paid $100 per month. She later invested and became part owner of the saloon, followed by a successful business in the speculation of buying pack mules. She later left her business in the care of someone else, deciding she was homesick to see her children.

She stayed in St. Louis for awhile, but two years after she made her first trip to California she started another one. The trip, however, did not go well. The party included fifteen men, twenty mules and horses and her cattle. When they reached alkali waters she lost 110 cattle, unable to prevent them from drinking the poison. Further down the trail, near the Humboldt River, they were attacked by Snake Indians. The party was forced to fight them off, Charley doing her part by shooting one Indian and stabbing another. One of the men was killed and Charley was severely wounded in her arm.

Upon reaching the Shasta Valley, Charley bought a small ranch to feed her stock until she could sell them. She returned to Sacramento to check on the business she had left behind, finding that it had done quite well. When she sold the business, her stock and the ranch, she had a tidy sum of $30,000 to send on to St. Louis. St. Louis, however, was not as exciting as the life Charley had found out west. She joined the American Fur Company and headed west again.

Charley returned to St. Louis for a time before heading out once again for Pike’s Peak and another gold rush – but not finding much gold for her efforts. She moved to a location closer to Denver and still not having much success, decided to open a bakery and saloon. After contracting mountain fever, she was forced to move to Denver. She rented a saloon and called it the “Mountain Boys Saloon” and kept it through the winter. By the spring of 1859 she was again restless, and deciding to try gold prospecting again she made $200 by the end of the summer. Returning to Denver she bought back her saloon, but soon events would take a disastrous turn for someone and her long-held secret would be revealed. In the spring of 1860, Charley was riding about three miles out of Denver and encountered someone she knew – Jamieson!

He recognized me at the same moment, and his hand went after his revolver almost that instant mine did. I was a second too quick for him, for my shot tumbled him from his mule just as his ball whistled harmlessly by my head. Although dismounted, he was not prostrate and I fired at him again and brought him to the ground. I emptied my revolver upon him as he lay, and should have done the same with its mate had not two hunters at that moment come upon the ground and prevented any further consummation of my designs.

Jamieson was not dead, however. The hunters made a litter to carry him back to Denver. Jamieson had severe wounds, although not fatal. He recovered and journeyed to New Orleans only to die of yellow fever soon after his arrival.

Charley’s identity had been revealed by Jamieson and he explained to the authorities the circumstances, relieving Charley of any blame for the attempts she had made on his life. Her story soon made the headlines – Horace Greeley wrote from Pike’s Peak to the New York Tribune about her story.

Charley continued dressing in male attire and during the winter of 1859-60 operated her saloon. She soon fell in love and married her bartender, H.L. Guerin. In the spring of 1860 they sold the saloon and moved to the mountains to open a boarding house and mine. That fall they returned to Missouri to be reunited with her children, which is where her memoir ended.

Quoted material in this article are excerpts from Charley’s memoir, Mountain Charley, or the Adventures of Mrs. E.J. Guerin, Who Was Thirteen Years in Male Attire. It’s an interesting read – especially the chapter (which I didn’t elaborate on) of her first trek to California. The book is a free download here and only 52 pages.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Tombstone Tuesday: One Moment – 293 Tombstones

It has been said that the tragedy that occurred seventy-seven years ago on Thursday, March 18, 1937 was the “day a town lost its future, the day a generation perished, the day when angels cried.” (Gone at 3:17). On that day, just minutes before school was to be dismissed for a much-anticipated three-day weekend, Lemmie R. Butler, a manual arts teacher, turned on a sanding machine and a spark escaped into the air, which unbeknownst to anyone was also mixed with gas.

It has been said that the tragedy that occurred seventy-seven years ago on Thursday, March 18, 1937 was the “day a town lost its future, the day a generation perished, the day when angels cried.” (Gone at 3:17). On that day, just minutes before school was to be dismissed for a much-anticipated three-day weekend, Lemmie R. Butler, a manual arts teacher, turned on a sanding machine and a spark escaped into the air, which unbeknownst to anyone was also mixed with gas.

The school had been built three years earlier and it was a show place, built not with taxes from the hard-working oil field families, but with money from the oil companies. It was possibly the wealthiest school district in the country, if not the world, at that time. Superintendent William Chesley Shaw was proud of his school, and even though the school was well-funded he still fretted over cost-savings – something that would prove fatal on that day in 1937.

This article is no longer available at this site. However, it will be enhanced and published later in a future issue of Digging History Magazine, our new monthly digital publication available by individual purchase or subscription. To see what the magazine is all about you can preview issues at our YouTube Channel. Subscriptions are affordable, safe and easy to purchase and the best deal for getting your “history fix” every month.

This article is no longer available at this site. However, it will be enhanced and published later in a future issue of Digging History Magazine, our new monthly digital publication available by individual purchase or subscription. To see what the magazine is all about you can preview issues at our YouTube Channel. Subscriptions are affordable, safe and easy to purchase and the best deal for getting your “history fix” every month.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Surname Saturday: Isham

Some of the earliest records of this surname (pronounced EYE-sham) occurred in eleventh century England. There are two Isham families that settled in the Colonies, one in Massachusetts and one in Virginia. The families migrated from Northamptonshire in England, where there was a village called Isham, near the Ise River, which is possibly where the family name was derived. Adding the suffix “ham” which means “home” to “Ise” would result in the family name of Isham.

Both of the American Isham families have interesting histories. One married into a well-known Virginia political family, the Randolphs, whose descendants include Thomas Jefferson and Edith Bolling Wilson (Woodrow’s second wife), Chief Justice John Marshall and General Robert E. Lee.

Captain Henry Isham

Henry Isham was born circa 1626-1628 in Northamptonshire to parents William and Mary Brett Isham. He migrated to Bermuda Hundred, Henrico, Virginia, situated along the James River, in 1656. He married Katherine (or Catherine) Banks, daughter of Christopher Banks, and they had at least three children: Henry, Mary and Anne.

Son Henry died young in 1678 and never married. Mary and Anne married prominent men, however.

Mary Isham Randolph

Mary Isham was born circa 1658 in Bermuda Hundred. In 1678 she married Colonel William Randolph, who had immigrated in 1674 and settled on “Turkey Island” in Henrico County, Virginia. William was a member of the House of Burgesses and served as its Speaker in 1698.

Mary bore nine children – seven sons and two daughters: William, Thomas, Isham, Richard, John, Henry, Edward, Mary, and Elizabeth.

Isham’s daughter, Jane, was the wife of Peter Jefferson and mother to Thomas Jefferson of Monticello.