In 1805, Lewis and Clark named them “Nez Perce”, which literally means “pierced nose”, except this tribe didn’t perform nose piercings – that was the Chinook tribe. The tribe’s name was actually “Nimi’puu” (Nee-Me-Poo) and meant “the people” or “we the people”. This tribe was indigenous to a vast area of land (17 million acres) which covered present day Washington, Oregon, Idaho and Montana. Rather than being one distinct tribe, this group actually consisted of various bands with somewhat different languages, managing to live together peacefully – the tribes (Shoshonis, Bannack and Blackfoot) to the south were not quite so friendly, however.

In 1805, Lewis and Clark named them “Nez Perce”, which literally means “pierced nose”, except this tribe didn’t perform nose piercings – that was the Chinook tribe. The tribe’s name was actually “Nimi’puu” (Nee-Me-Poo) and meant “the people” or “we the people”. This tribe was indigenous to a vast area of land (17 million acres) which covered present day Washington, Oregon, Idaho and Montana. Rather than being one distinct tribe, this group actually consisted of various bands with somewhat different languages, managing to live together peacefully – the tribes (Shoshonis, Bannack and Blackfoot) to the south were not quite so friendly, however.

The Nez Perce acquired horses sometime in the mid-1700’s, becoming expert horseman, and by the nineteenth century were the largest owner of horses in North America. They were a nomadic tribe, moving with the seasons to fish, hunt and gather – salmon, deer, elk, berries, pine nuts, sunflower seeds, wild potatoes and carrots.

The Nez Perce acquired horses sometime in the mid-1700’s, becoming expert horseman, and by the nineteenth century were the largest owner of horses in North America. They were a nomadic tribe, moving with the seasons to fish, hunt and gather – salmon, deer, elk, berries, pine nuts, sunflower seeds, wild potatoes and carrots.

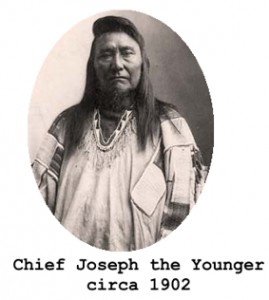

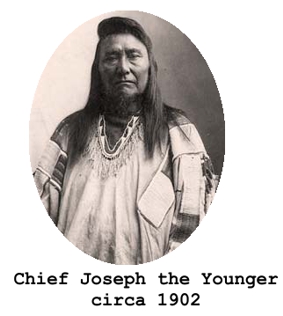

Two of the most prominent tribal leaders were Chief Joseph the Elder and Chief Joseph the Younger. The elder had taken the Christian name of “Joseph” when he converted to Christianity and was baptized at the Lapwai mission in 1838. His son was born in 1840 and given the name “Hin-mah-too-yah-lat-kekt” or “Thunder Rolling Down the Mountain”, but became known as “Joseph the Younger”.

Joseph the Elder promoted peace with the white man, signing a treaty with the United States government in 1853 which set up a large reservation spanning across Oregon and into Idaho. When the gold rush brought more white settlers, in 1863 the government took more land and relegated the tribe to an area of land in Idaho which was one-tenth the size of the original allocation. At this point, Joseph the Elder denounced the United States government, destroyed the American flag and his Bible, refused to move his people to the Wallowa Valley and refused to sign another treaty. One faction of the tribe, headed by the Head Chief Lawyer and others decided to honor the treaty, and thus the tribe was split.

Joseph the Elder promoted peace with the white man, signing a treaty with the United States government in 1853 which set up a large reservation spanning across Oregon and into Idaho. When the gold rush brought more white settlers, in 1863 the government took more land and relegated the tribe to an area of land in Idaho which was one-tenth the size of the original allocation. At this point, Joseph the Elder denounced the United States government, destroyed the American flag and his Bible, refused to move his people to the Wallowa Valley and refused to sign another treaty. One faction of the tribe, headed by the Head Chief Lawyer and others decided to honor the treaty, and thus the tribe was split.

When Joseph the Elder died in 1871, leadership passed to Joseph the Younger. Like his father before him, Joseph refused to cede the land originally given to the tribe in 1853. Through negotiations and debates with the federal government, Joseph elevated his stature as a statesman, however. In 1873, it appeared that his efforts had been successful in allowing his people to remain, but the government reversed itself and beginning in 1877 threats of military enforcement and engagement were circulated.

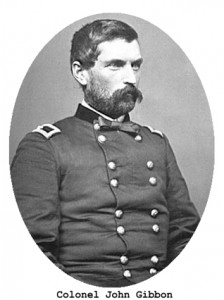

Chief Joseph began to sense that he would not succeed and decided to lead his people towards Canada. His band of warriors fought a series of skirmishes and four major battles along the way – the third was called the Battle of Big Hole. Major General John Gibbon had served in the Mexican-American War and the Civil War. After the Civil War he continued to serve, but reverted to the rank of Colonel while commanding the infantry based at Fort Ellis in Montana Territory.

Colonel Gibbon received a telegram from General Oliver Howard directing him to cut off the fleeing Nez Perce. On his way to intercept and attack the Nez Perce, he was joined by forty-five citizens who believed that the Indians should be punished. Gibbon and his troops were averaging thirty to thirty-five miles per day and estimated that for every day the Nez Perce traveled, they were traveling the equivalent of two, so it was only a matter of time until they caught up to them. Along the route they gathered information – there were still at least 400 warriors and approximately 150 women and children, in addition to 2,000 horses and plenty of guns and ammunition.

Colonel Gibbon received a telegram from General Oliver Howard directing him to cut off the fleeing Nez Perce. On his way to intercept and attack the Nez Perce, he was joined by forty-five citizens who believed that the Indians should be punished. Gibbon and his troops were averaging thirty to thirty-five miles per day and estimated that for every day the Nez Perce traveled, they were traveling the equivalent of two, so it was only a matter of time until they caught up to them. Along the route they gathered information – there were still at least 400 warriors and approximately 150 women and children, in addition to 2,000 horses and plenty of guns and ammunition.

When some of the citizen troops wanted to turn back to attend to affairs at home, Gibbons implored them to continue knowing that without them they would likely be outnumbered. After a promise that any horses captured would be equally divided among them, the citizens enthusiastically agreed to continue. The Colonel then sent Lieutenant James H. Bradley, who was joined by Lieutenant J.W. Jacobs, to take their troops and strike the Nez Perce camp before daylight the next day. They thought if they were able to stampede the stock the Indians would begin to disperse and victory would be certain.

However, the trail proved to be more difficult than anticipated and they were unable to reach the camp before daylight. Consequently, the Indians had broken camp and traveled on – but their journey that day was short and they again encamped at the mouth of Trail Creek. Lt. Bradley would then conceal his troops in the hills and await the arrival of the infantry. Gibbons pressed on through the day and arrived at Bradley’s camp around sundown. He was then informed by Bradley that it was likely the Nez Perce would remain at that camp for several days since the women were seen cutting and peeling lodge poles to erect shelter.

Before Colonel Gibbon’s arrival, Bradley had sent out men to ascertain the exact position of the camp and its activities. Gibbon took a nap and at 10:00 p.m. he was awakened to begin preparations for the troops to move as quickly and quietly as possible to the encampment. After five miles without detection, the troops reached an area which opened up into the valley of the Big Hole River. They could see smoldering camp fires in the distance and were able to proceed to within a few hundred yards of the quiet, sleeping camp.

The troops encountered a group of horses and Gibbon was cautioned that if they tried to move the animals out they might lose the element of surprise. If he had known there was in fact no one guarding the horses that night, the Indians would have been placed in an extremely vulnerable situation, all without the Army firing a shot. By 2:00 a.m. on the morning of August 9, 1877, the troops were within approximately 150 yards of the camp, waiting quietly in the cold for stirrings in the camp. Around 3:00 squaws came out of their tents to stoke the waning fires and then returned to their beds.

At dawn the troops began to quietly move again. An Indian had arisen and mounted his horse and headed toward the herd. As he emerged from a thicket of willows, he and his horse were shot. The standing orders were to charge the camp as soon as the first shot was fired. The troops were more than ready and the element of surprise was complete. According to The Battle of the Big Hole by George O. Shield, “squaws yelled, children screamed, dogs barked, horses neighed and snorted, and many of them broke their fetters and fled.”

Even the warriors, usually so stoical, and who always like to appear incapable of fear or excitement, were, for the time being, wild and panic-stricken like the rest. Some of them fled from the tents at first without their guns and had to return later, under a galling fire, and get them. Some of those who had presence of mind enough left to seize their weapons were too badly frightened to use them at first and stampeded, like a flock of sheep, to the brush.

The soldiers shot to kill and “[M]any an Indian was cut down at such short range that his flesh and clothing were burned by the powder from their rifles.” The Indians, however, recovered from the overwhelming surprise and began to fight back. Only twenty minutes had transpired after the first shot was fired when the troops had secured victory – orders were then given to burn the camp, but several Indians had already fled and because of the dampness of the grass from the early morning dew the destruction was not complete.

The death toll was significant for both sides – the Army had lost 29 men with 40 wounded and they counted 89 Nez Perce bodies, mostly women and children. The battle had rendered a major blow, but not a fatal one, as the Indians continued fleeing to the northeast, intent on reaching Canada and a new home.

Two months later troops led by Colonel Nelson Miles again overtook the Nez Perce, decisively defeating them at the Battle of the Bear Paw Mountains. Chief Joseph and his remaining tribe members had traveled to within 40 miles of the Canadian border when he finally gave up saying:

I am tired of fighting. My people ask me for food, and I have none to give. It is cold, and we have no blankets, no wood. My people are starving to death. Where is my little daughter? I do not know. Perhaps even now she is freezing to death. Hear me, my Chiefs, I have fought; but from where the sun now stands, Joseph will fight no more.

The Nez Perce were sent to Kansas and then to Oklahoma Indian Territory, although General Miles had promised they would be allowed to return to their country. Many years later a small band was allowed to return to the Colville Reservation in eastern Washington, however. Chief Joseph was allowed to travel to Washington, D.C. to tell his story and he gave an impassioned speech, which was published in the April 1879 issue of the North American Review:

I only ask of the Government to be treated as all other men are treated. If I cannot go to my own home, let me have a home in some country where my people will not die so fast. I would like to go to Bitter Root Valley. There my people would be healthy; where they are now they are dying. Three have died since I left my camp to come to Washington.

When I think of our condition my heart is heavy. I see men of my race treated as outlaws and driven from country to country, shot down like animals.

I know that my race must change. We can not hold our own with the white men as we are. We only ask an even chance to live as other men live. We ask to be recognized as men. We ask that the same law shall work alike on all men. If the Indian breaks the law, punish him by the law. If the white man breaks the law, punish him also.

Let me be a free man—free to travel, free to stop, free to work, free to trade where I choose, free to choose my own teachers, free to follow the religion of my fathers, free to think and talk and act for myself—and I will obey every law, or submit to the penalty.

Whenever the white man treats the Indian as they treat each other, then we will have no more wars. We shall all be alike—brothers of one father and one mother, with one sky above us and country around us, and one government for all. Then the Great Spirit Chief who rules above will smile upon this land, and send rain to wash out the bloody spots made by brothers’ hands from the face of the earth. For this time the Indian race are waiting and praying. I hope that no more groans of wounded men and women will ever go to the ear of the Great Spirit Chief above, and that all people may be one people.

In-mut-too-yah-lat-lat has spoken for his people.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Trackbacks/Pingbacks