Motoring History Monday: America’s First Coast-to-Coast Automobile Trip

In honor of the upcoming Memorial Day weekend when many Americans “hit the road” to officially begin summer, today’s article is about the first successful coast-to-coast American road trip.

In honor of the upcoming Memorial Day weekend when many Americans “hit the road” to officially begin summer, today’s article is about the first successful coast-to-coast American road trip.

On May 19, 1903, Horatio Nelson Jackson was in San Francisco on business. His primary residence was in Vermont where he had been a physician. Following a bout with tuberculosis he spent time in California and in May of 1903, having given up the practice of medicine three years earlier, was returning from Alaska were he had overseen some gold mine investments.

On May 19, 1903, Horatio Nelson Jackson was in San Francisco on business. His primary residence was in Vermont where he had been a physician. Following a bout with tuberculosis he spent time in California and in May of 1903, having given up the practice of medicine three years earlier, was returning from Alaska were he had overseen some gold mine investments.

While at the University Club he overheard a group of men talking about the new horseless carriage – in their opinion it would never be able to make a cross-country trip. Horatio thought otherwise and boastfully wagered $50 claiming he could make the trip in less than three months. The wager must have seemed impetuous since Horatio did not own an automobile, and likely had very little, if any, experience driving one.

This article is no longer available for free at this site. It was re-written and enhanced, complete with footnotes and sources and has been published in the June 2018 issue of Digging History Magazine. Should you prefer to purchase the article only, contact me for more information.

This article is no longer available for free at this site. It was re-written and enhanced, complete with footnotes and sources and has been published in the June 2018 issue of Digging History Magazine. Should you prefer to purchase the article only, contact me for more information.

I invite you to check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Surname Saturday: Gwinnett

The “Gwinnett” surname is of Welsh origin, first seen in Herefordshire where the family seat was held. The name derived from the Old Welsh nickname “Gwynn” for one who was fairly complected and had blonde hair. The area in Wales known as “Gwynnedd” was home to the family bearing this surname.

Spelling variations of this surname include: Gwinnett, Gwinet, Gwinett, Gwinnet and others. The subject of today’s article, Button Gwinnett, hailed from Gloucestshire. One family historian estimates that the Gwinnett family arrived in Gloucestshire around 1575, leaving the Gwynnedd area of North Wales.

Button Gwinnett

Button Gwinnett was born in Down Hatherly, Gloucestershire, England in about 1735 (at least that is when he was baptized), the son of Reverend Samuel and Anne (Emes) Gwinnett and the oldest of seven children. It is said that he acquired his unusual forename from his godmother Barbara Button. Young Button was educated in Gloucestershire and became a merchant. In 1757 he married Ann Bourne and by 1762 he and Ann decided to immigrate to America.

Button Gwinnett was born in Down Hatherly, Gloucestershire, England in about 1735 (at least that is when he was baptized), the son of Reverend Samuel and Anne (Emes) Gwinnett and the oldest of seven children. It is said that he acquired his unusual forename from his godmother Barbara Button. Young Button was educated in Gloucestershire and became a merchant. In 1757 he married Ann Bourne and by 1762 he and Ann decided to immigrate to America.

The Gwinnett family first landed in Charleston, South Carolina and then continued on to Savannah, Georgia to became a merchant. When his business failed, he sold his stock and purchased St. Catherine’s Island off the coast of Georgia and became a farmer. He turned to politics in 1767, serving as a justice of the peace and later in the Georgia Lower Assembly. After limited success as a planter, Button abandoned politics to concentrate on paying his debts, selling off most of his property, including St. Catherine’s.

It is said that Button had doubts about the colonies succeeding in breaking away from England. After leaving politics he was still active in his community and parish. After coming under the influence of Lyman Hall, Button Gwinnett became an emboldened radical. He was present at Peter Tondee’s tavern in Savannah on July 24, 1774 to debate the right of England to continue to pass laws which were burdensome to the colonists, referred to as “Intolerable Acts”. By 1775 his views had changed and he came out forcefully in favor of the rights of colonists to govern themselves.

It is said that Button had doubts about the colonies succeeding in breaking away from England. After leaving politics he was still active in his community and parish. After coming under the influence of Lyman Hall, Button Gwinnett became an emboldened radical. He was present at Peter Tondee’s tavern in Savannah on July 24, 1774 to debate the right of England to continue to pass laws which were burdensome to the colonists, referred to as “Intolerable Acts”. By 1775 his views had changed and he came out forcefully in favor of the rights of colonists to govern themselves.

In early 1776 he was elected to Georgia’s general assembly in Savannah, which gave him a seat in the national Congress. He traveled to Philadelphia to join other delegates and on July 2, 1776 voted in favor of the Declaration of Independence before it was presented as a “fair copy” to Congress on July 4. On August 2, 1776 he signed his name to the revolutionary document, just above his mentor Lyman Hall:

While serving in the Continental Congress, the opportunity for Button to serve as a brigadier general in the 1st Regiment of the Continental Army arose. However, the position went to his political rival Lachlan McIntosh, embittering Gwinnett. He returned to Georgia and continued to serve in the legislature. In 1777 he assisted in drafting the Georgia state constitution.

In the background he continued to oppose McIntosh, and after Button became president of the Council of Safety, he went even further in his attempts to thwart his rival. To assert his own power Button undertook an attempted invasion of Florida, leading the troops himself. It was an ill-conceived plan and after its failure, Gwinnett was charged with malfeasance. He was cleared of the charges and then ran (unsuccessfully) for Governor.

McIntosh had publicly denounced Gwinnett, and to defend his honor Button challenged him to a duel. They dueled at the distance of only twelve feet and both were severely wounded. However, Button Gwinnett was the only one mortally wounded. He died on May 19, 1977 and was buried in Savannah’s Colonial Park Cemetery. Gwinnett County, Georgia is named after Button Gwinnett.

Today his signature is one of the most rare and sought after of all the signers of the Declaration of Independence. A letter with his signature sold at auction in New York in 1979 for $100,000. By 1983 its value had risen to $250,000.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Feisty Females: Cynthia Ann Parker

In 1833 two hundred men, women and children made their way from Illinois to Texas led by Reverend Daniel Parker. They crossed the Mississippi and continued their journey southward through Missouri, Arkansas and Louisiana until in mid-November they reached the Sabine River in eastern Texas. Camping near San Augustine on November 12, they witnessed a fearful and awesome sight which came to be known as the “Night the Stars Fell”.

In 1833 two hundred men, women and children made their way from Illinois to Texas led by Reverend Daniel Parker. They crossed the Mississippi and continued their journey southward through Missouri, Arkansas and Louisiana until in mid-November they reached the Sabine River in eastern Texas. Camping near San Augustine on November 12, they witnessed a fearful and awesome sight which came to be known as the “Night the Stars Fell”.

In the predawn hours of November 13, the sky lit up with huge shooting stars. All of North America was witness to this phenomenal event. No doubt some thought it might be God’s judgment coming down on them. Daniel Parker was troubled as well and no one could sleep after the event – the remainder of the night was spent in prayer.

Hostile Indians still roamed the plains, and the Parker family was surely aware of the dangers they would face in Texas. James Parker was the first of his family to make the trek to Texas in 1831. He returned to Illinois with a good report, even though while in Texas one of his neighbors was shot and scalped. Nevertheless, Daniel, his sons and their families and members of their Illinois congregation set out to found a new colony in Texas.

Hostile Indians still roamed the plains, and the Parker family was surely aware of the dangers they would face in Texas. James Parker was the first of his family to make the trek to Texas in 1831. He returned to Illinois with a good report, even though while in Texas one of his neighbors was shot and scalped. Nevertheless, Daniel, his sons and their families and members of their Illinois congregation set out to found a new colony in Texas.

Many of their group chose to settle near small towns and villages, but James and Silas Parker picked an isolated spot near the Navasota River to put down their roots. The area was surrounded by Indians who had lived there for hundreds of years – Caddos, Wichitas and Kichais who were primarily farmers and hunters. To the north and west were the more warlike Comanches, Apaches and Kiowas.

James and his wife Martha had six children and Silas and his wife Sarah had four, their oldest child a blond blue-eyed daughter named Cynthia Ann. It soon became apparent that the Indians, especially the more aggressive Comanches, would threaten their peace and safety. In 1835 they built “Fort Parker” – six cabins and two blockhouses surrounded by a twelve-foot tall fence. Later the Texas Rangers would use the fort as a base of operations and Silas secured a contract to hire twenty-five men to patrol the area and prevent Indian incursions.

Attempts to live peacefully with the Indians had been hit and miss. The winter of 1836 was harsh – hunger and disease were especially rampant among the Parker’s Indian neighbors. One of the young Comanche warriors, Peta Nocona, blamed the white settlers for his people’s woes and wanted revenge. In early 1836 the territory was beginning to stir with talk of independence from Mexico. Daniel Parker was one of the original signers of the Texas Declaration of Independence.

Following the Battle of the Alamo, the Parkers fled toward the Trinity River, fearful that the Mexicans and Indians would form an alliance and attack their settlement. Rains had been falling steadily and the Trinity River had risen so dramatically that it was impossible to cross. Instead they were forced to camp out along the western bank and wait out the storm. But, Sam Houston and his army had overcome and defeated Santa Anna’s forces at San Jacinto. Settlers were then able to return and proceed with their spring planting.

Settlers had been warned by Houston about possible Indian attacks. Foolishly, James Parker, who thought he knew all there was to know about Indians, disbanded the Ranger company. He and his neighbors would defend themselves. Apparently he felt there was nothing to fear – how wrong he was.

On the morning of May 19, 1836 most of the men were out in the fields about a mile away from the stockade when a large group of Indians rode up to the fort on horseback carrying a white flag. No one seems to know exactly how many there were, perhaps hundreds by some accounts. Benjamin Parker asked what they wanted and the Indians demanded a steer. Benjamin went to Silas to tell him about the demands, and although Silas pleaded with him not to negotiate with them, Benjamin walked back to where the Indians were gathered. It proved to be a fateful walk.

Benjamin was surrounded, clubbed and left for dead. Pandemonium erupted and the women and children began to flee. Silas Parker took one shot and was then surrounded, clubbed and scalped. Other men were brutally killed and scalped in front of the women and children. The warriors raided and pillaged the stockade, and when the raid was concluded they had killed five and taken five captive – with no casualties of their own. One of the five captives was Silas Parker’s nine year-old daughter Cynthia Ann.

Rescue efforts were begun to reclaim the captives, and James Parker would spend a great deal of time over the ensuing years to find them. Four of the captives would eventually be released, but Cynthia Ann became so inculturated into the Comanche tribe that she forgot how to speak English. A Comanche couple adopted her and raised her as their own daughter. In a strange twist, she married Peta Nocona who had stirred up the warriors to attack the settlers.

Some claim that in the mid-1840’s she was asked by her brother John to return to her family but refused. She was happily married to Nocona and had children with him. One newspaper account on April 29, 1846 described an encounter Colonel Leonard Williams had while patrolling along the Canadian River. He offered a ransom for Cynthia Ann but the tribal elders refused to release her. It’s highly doubtful she would have agreed to leave even if she had been approached directly by Williams. She must have been special to her husband since it is said that he forsook the Comanche tradition of having multiple wives — Cynthia Ann was his one and only.

On December 18, 1860, almost twenty-five years after her capture, Texas Rangers led by Lawrence Sullivan “Sul” Ross attacked Nocona’s camp near Mule Creek, a tributary of the Pease River. Although Nocona was wounded he managed to escape with his two sons Quanah and Pecos. Imagine how surprised the Rangers were to find a “Comanche” with blue eyes. Cynthia Ann was “re-captured” along with her young daughter. She agreed to meet with her uncle Isaac Parker as long as her sons, if found, were returned to her.

By this time she claimed not to know her birth name nor where she originally came from. Still, those who were interviewing her suspected she was Cynthia Ann Parker. To the white man’s world she was an oddity and people would gather to gawk at her. According to Glenn Frankel, author of The Searchers: The Making of an American Legend:

Medora Robinson Turner, a Fort Worth schoolgirl, recalled being let out of class one day and taken to a retail store, where a crowd had gathered to gawk at the celebrity captive. “She looked like a squaw,” Turner recalled. “She stood on a large wooden box surrounded by the curious spectators. She was bound with rope. She wore a torn calico dress. She made a pathetic figure. Tears were streaming down her face, and she was muttering in the Indian language.”

Attempts to inculturate her back into her birth family and the white man’s world were largely unsuccessful. According to Frankel:

She had effectively reversed the narrative and subverted its meaning: instead of being abducted by Comanches, Cynthia Ann felt abducted by her white family. She was, in the deepest sense, a prisoner of war. The Parkers, as good Baptists, believed in the power of redemption. But what about someone who refused to be redeemed?

Her family continued to reach out to her, teaching her the Bible and praying with her but nothing seemed to change her, at least to their satisfaction. Frankel relates that one day a relative slaughtered a cow and Cynthia Ann and her daughter rushed out to the carcass. After it was opened they grabbed the kidneys and liver and started eating and dancing while blood was running down their faces – undoubtedly a disturbing sight to her family.

In February of 1861 a now iconic photo was taken of Cynthia Ann and her daughter. Glenn Frankel aptly described it:

In February of 1861 a now iconic photo was taken of Cynthia Ann and her daughter. Glenn Frankel aptly described it:

In the photograph that has survived from that day, Cynthia Ann’s expression is hard and raw as granite. Her face is flat, weathered, and heavyset. Her lips are sealed shut. Her dark hair had been hacked short in the manner of a Comanche in mourning. She is wearing a thin bandanna around her neck and a borrowed muslin dress unbuttoned where her raven-haired little girl suckles at her right breast. There is no comprehension; at best, there is resignation, and lurking behind it a palpable sense of fear.

After a time her name and fame faded into the background, the public perhaps believing her to be beyond help. Although her daughter Prairie Flower later attended school and learned to read and write English, Cynthia Ann still kept to her Indian ways. Her skills as a tanner provided a reliable income.

Prairie Flower either died of smallpox or influenza in 1863 or she was spirited away to New Orleans to be raised, her death faked and her name changed – depending on which account you believe (or disbelieve). No one seems to really now exactly what happened to her. The claim that she died in 1863 is followed up by another claim that Cynthia died not long afterwards. However, in 1870 the census enumerated Cynthia Ann Parker in the household of one of her relatives.

Frankel points out that it’s more plausible to believe that Prairie Flower died around the age of nine of brain fever and was buried in the Fosterville cemetery. After that Cynthia Ann’s own health and mental status began to deteriorate. Her family would later claim that she eventually returned to Christianity, insisting on being baptized by immersion into the Methodist church. In March of 1871 Cynthia Ann Parker died and was buried in the Fosterville cemetery next to her daughter.

Well over a hundred years later she would be hailed as a feminist role model. In 2003 an article in Texas Monthly declared:

Strong as buffalo hide, family-loving and high-spirited despite dire circumstances, Cynthia Ann demonstrated the same qualities that have ennobled iconic Texans from Mary Maverick to Barbara Jordan, Ima Hogg to Lady Bird Johnson. Maybe the reason we can’t let go of Cynthia Ann is because she was the original tough Texas woman.

If one could interview Cynthia Ann today, I doubt she would look upon herself in the way she has been idolized. Her life was book-ended by two tragedies – seeing her white family massacred and later seeing her Comanche family torn apart. To the person experiencing such atrocities, it would hardly seem idyllic or even heroic to endure. One legacy, however, remained which she would never know about – her son Quanah Parker (he later took her English last name) survived the attack at Mule Creek and was later instrumental in his role as statesman in saving the Comanche nation.

Glenn Frankel’s account of the Parkers and Cynthia Ann’s capture and recapture was fascinating and well-researched. Look for a book review soon.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

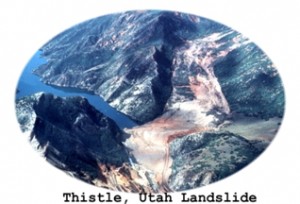

Ghost Town Wednesday: Thistle, Utah

Way back when, long before settlers began making their treks west, this area of Utah was along a route used by Native Americans as they made their seasonal migrations in the spring and fall. The first recorded European expedition was made in 1776 by Francisco Atanasio Domínguez and Silvestre Vélez de Escalante, two Franciscan monks who set out with cartographer Don Bernardo Miera y Pacheco to map a route from Santa Fe to the missions in California.

Way back when, long before settlers began making their treks west, this area of Utah was along a route used by Native Americans as they made their seasonal migrations in the spring and fall. The first recorded European expedition was made in 1776 by Francisco Atanasio Domínguez and Silvestre Vélez de Escalante, two Franciscan monks who set out with cartographer Don Bernardo Miera y Pacheco to map a route from Santa Fe to the missions in California.

In the 1840’s migrants from areas previously considered “the west” began making their way into territory opened by massive land acquisitions in the early nineteenth century. The Mormons from Nauvoo, Illinois began to migrate to the area, the first group being the Pace family who arrived in 1848. Other Mormons would join them later to homestead, primarily ranching and farming until the railroads arrived in the late 1870’s.

In the 1840’s migrants from areas previously considered “the west” began making their way into territory opened by massive land acquisitions in the early nineteenth century. The Mormons from Nauvoo, Illinois began to migrate to the area, the first group being the Pace family who arrived in 1848. Other Mormons would join them later to homestead, primarily ranching and farming until the railroads arrived in the late 1870’s.

The Utah and Pleasant Valley Railway, a narrow-gauge spur line, was the first railroad built to service nearby coal mines. When the railway went bankrupt in 1882, the Denver and Rio Grande Western acquired it and laid standard gauge track, joining it with track previously laid out to western Colorado, completing a direct route from Denver to Salt Lake City.

The railroad had facilities in Thistle to service trains and to also prepare them for a steep grade change over Soldier Summit. Before on-board dining, trains would stop in Thistle for meal service. Other rail lines were built in the area, further boosting Thistle’s economy. Another economic boost occurred between 1892 and 1914 when asphaltum was discovered nearby.

By 1920 the town had just over four hundred residents, according to census records, although in 1917 there had been around six hundred. In addition to railroad services, the town had other businesses such as a barber shop, saloon, general stores, restaurants and a two-story schoolhouse built in 1911. Technology, specifically the introduction of diesel train engines, led to a population decline for Thistle beginning in the 1950’s. The depot was demolished in 1972 and the post office closed two years later.

By the early 1980’s very few residents remained in Thistle. The fall-winter season of 1982-1983 had brought record rain and snowfall. The snow pack was extremely deep and when temperatures began to rise, the snow melted rapidly. Although trains still came through Thistle, maintenance had fallen behind and officials were meeting in Denver on April 13 to discuss the problems. That same day a portion of US-6 buckled and maintenance crews had their hands full trying to keep the highway open, but trains continued to pass through, although speed was limited to only ten miles per hour.

After the Rio Grande Zephyr passed through on the evening of the 14th around 8:30 p.m., the railroad track and US-6 were closed after midnight when the rising waters of the Spanish Forks River inundated both. By the 16th, the tracks were completely buried in mud and residents were given orders to evacuate. Residents only had a couple of hours to gather their belongings. One resident, an elderly woman, refused to evacuate and was later forcibly removed. Two days later the entire town was under water.

Even after attempts to stem the advance of the landslide (advancing at the rate of three feet per hour), the nearby canyon was filled with mud, creating a natural dam which was six hundred feet wide and about fifty feet deep. As the dam area grew, the water depth behind it increased to over eighty feet. Damages exceeded $220 million, which made this disaster the costliest landslide to date in United States history. Thistle the town was no more – now it was “Thistle Lake”. Even today, after the “lake” was drained, the town site and remaining structures have a “subterranean feel” with partially submerged homes and stores still visible.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Tombstone Tuesday: Early Greathouse

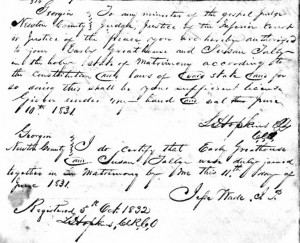

Early Greathouse was born on October 4, 1810 in Clarke County, Georgia to parents Abraham and Sarah Curley Greathouse. The family later migrated down to Newton in Baker County, Georgia where Early married Susan Elizabeth Talley on June 11, 1831.

Early Greathouse was born on October 4, 1810 in Clarke County, Georgia to parents Abraham and Sarah Curley Greathouse. The family later migrated down to Newton in Baker County, Georgia where Early married Susan Elizabeth Talley on June 11, 1831.

Early and Susan made their home in Newton County for a time following their marriage, later migrating to Troup County in western Georgia. Early converted to the Baptist faith in 1838 and he and his family attended Troup County Line Baptist Church. In 1846 he was ordained as a minister of the gospel and later served as pastor at various churches. Early was also a farmer and slave owner; in 1840 he owned five. In 1856 Early and his family migrated to Tallapoosa County, Alabama, settling on a thousand acre farm near present day Lake Martin.

Early and Susan had several children. Their first, Sarah Elizabeth (“Sallie”) was born on March 19, 1832 in Newton County, followed by:

John Alexander – March 9, 1834

Seaborn J. – March 16, 1836

William Early – September 6, 1839

Augustus Delaware – March 17, 1841

Mary Frances (“Fannie”) – September 6, 1843

Thomas D. – April 15, 1846

Robert W. – June 5, 1848

Cary J. – December 15, 1851

James Littleton – April 13, 1854

Early Barham – July 13, 1857

Some family historians speculate that there were more children, but these are the only ones enumerated in census years 1850, 1860 and 1870. Cary died at the age of eleven on May 9, 1863, and was buried in the Greathouse family cemetery in Tallapoosa County.

Not only was Early a successful farmer and minister, he was a statesman as well. He served four terms as a representative in the Alabama legislature. He and his family were staunchly pro-slavery and sons Augustus, Seaborn, Thomas, John and William joined the Confederate army. Augustus was wounded twice but survived the war, as did Thomas and John.

Not only was Early a successful farmer and minister, he was a statesman as well. He served four terms as a representative in the Alabama legislature. He and his family were staunchly pro-slavery and sons Augustus, Seaborn, Thomas, John and William joined the Confederate army. Augustus was wounded twice but survived the war, as did Thomas and John.

Seaborn enlisted in Company A of the 1st Alabama Infantry (“Tallapoosa Rifles”) as a private on March 19, 1862. His tombstone indicates that he fought at the Battle of Shiloh less than a month later. He was captured at Port Hudson, Louisiana on July 9, 1862 and paroled on July 11, 1863. He died on August 21, 1863 (less than four months after Cary died) and is buried in the Greathouse family cemetery in Tallapoosa County. I couldn’t find any records for the cause of his death, whether war-related, disease or natural causes.

William enlisted in Company K of the 29th Alabama Infantry and was also at the Battle of Shiloh where he was mortally wounded, dying at Holly Springs, Mississippi on June 18, 1862. He is buried in the same cemetery (or at least there is a tombstone there) as Cary and Seaborn. The years 1862 and 1863 were tragic for the Greathouse family.

Mary Francis (“Fannie”) had married George Witter in 1859 and lived in Atlanta during the war. A family legend claims that Fannie yelled at General Sherman as he was passing by: “You want to burn my house, then you have to burn me and the children.” Whether true or not, it has been passed down through the generations.

After the Civil War concluded, Alabama called a convention to draft a new constitution. Early was one of the delegates representing Tallapoosa County and said to have been a “leading spirit of that assembly.” The Greathouse family (including, it appears, all of the remaining sons and daughters and their families) began migrating to Texas in the late 1860’s, many of them settling in Bell County. The Reconstruction period following the war was a turbulent and volatile time in the county. Federal troops were stationed in Belton – feuds and political vigilantism were rampant.

Early and Sarah arrived in 1870 and founded two churches, Knob Creek and Mount Vernon Baptist. According to Bell County history, Early was “a Christian gentleman of more than ordinary ability.” In addition to founding two churches and serving as pastor at Mount Vernon, Early also built the first cotton gin in Bell County.

In 1871 he set aside land for a Greathouse family cemetery. His granddaughter, Mattie Lee Clopton, was the first to be buried there. She was twelve years old and the daughter of Sarah. Early’s mother Sarah had been living with his family for quite some time. She died on May 4, 1878 at the age of 90 and was buried in the family cemetery.

Early served as pastor at Mount Vernon until his health began to deteriorate. He died on August 10, 1885 at the age of seventy-four, and Susan died on April 25, 1886. Both are buried in the family cemetery, along with several other members of their family, extended family and members of the local community. The cemetery is now an official Texas historical landmark.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

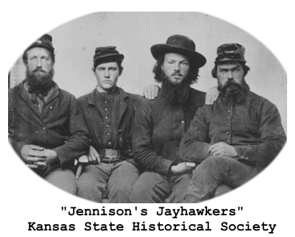

Military History Monday: Jennison’s Jayhawkers

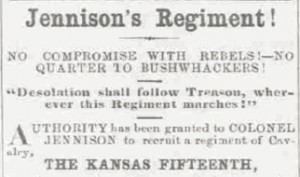

This Civil War regiment, the 7th Kansas Cavalry, was organized by Charles Rainsford Jennison and became known as “Jennison’s Jawhawkers.” By the time the regiment was mustered in on October 28, 1861, the terms “jayhawk,” “jawhawker,” and “jayhawking” were already part of the national lexicon long before the Civil War broke out in April of 1861.

This Civil War regiment, the 7th Kansas Cavalry, was organized by Charles Rainsford Jennison and became known as “Jennison’s Jawhawkers.” By the time the regiment was mustered in on October 28, 1861, the terms “jayhawk,” “jawhawker,” and “jayhawking” were already part of the national lexicon long before the Civil War broke out in April of 1861.

The term “jayhawk” and it’s various iterations seems to have originated as early as the late 1840’s along the Kansas-Missouri border. There are several theories as to how the term came into usage, but as far as a Kansan is concerned it is deeply rooted in the state’s history – it’s also Kansas University’s mascot. The name combines two birds, since there is no such thing as a “jayhawk” in nature – so mythically speaking it’s sort of a cross between a quarrelsome, nest-robbing blue jay and a sparrow hawk, a stealthy hunter.

After the Kansas-Nebraska of 1854 was enacted, there was “Bloody Kansas” or as I like to call it, the “Civil War before THE Civil War”. Missouri counties which bordered Kansas were pro-slavery while Kansas was being flooded with anti-slavery advocates. In Missouri the “Border Ruffians” not only made incursions into Kansas Territory to harass, pillage and kill, they also sent illegal voters to Kansas to elect a pro-slavery legislature.

After the Kansas-Nebraska of 1854 was enacted, there was “Bloody Kansas” or as I like to call it, the “Civil War before THE Civil War”. Missouri counties which bordered Kansas were pro-slavery while Kansas was being flooded with anti-slavery advocates. In Missouri the “Border Ruffians” not only made incursions into Kansas Territory to harass, pillage and kill, they also sent illegal voters to Kansas to elect a pro-slavery legislature.

Sparring with the “Border Ruffians” along the border were the Kansas “Jayhawkers.” As time went on and hostilities escalated, it would become harder to distinguish between the two after the Jayhawkers began using the same tactics – no wonder they called it “Bloody Kansas.” One of the more unscrupulous Jayhawkers was Charles Jennison.

Jennison was born on June 6, 1834 in upstate New York in an area known as the “Burned-Over District”, so named for its evangelical fervor. He migrated with his family to Albany, Wisconsin in 1846 where he continued his education, studied medicine and practiced for a time. In 1857 he made the trek westward to Kansas Territory, settling first in Osawatomie. By that time, John Brown had already made his anti-slavery views well-known, not to mention the attack that Brown and others carried out on Lawrence in 1856.

Jennison, like Brown, was stridently anti-slavery. He appears to have proclaimed himself “the law” in at least one case. The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 required that fugitive slaves be returned to their masters. Russell Hinds crossed over the Missouri state line into Kansas to visit his mother, only to be accused of transporting a fugitive slave back to Missouri (there were rewards for doing so). Jennison and nine other men held a mock trial and found Hinds guilty and hanged him. This dangerous type of “frontier justice,” coupled with his penchant for plundering in order to enrich himself, gave him his well-earned reputation as a ruthless and unscrupulous character.

By 1861 he had migrated to Mound City, Kansas and was still carrying on his anti-slavery campaign. On February 19, 1861 he was commissioned as a captain of the Mound City militia. Less than six months later, on September 4, he received a promotion to colonel from Kansas Governor Charles L. Robinson. He set about to organize the 7th Kansas Cavalry which would later become known as “Jennison’s Jayhawkers.” After mustering in on October 28, the regiment went to work patrolling the western Missouri border.

Just because he was now a commissioned military officer didn’t prevent Jennison from continuing his unscrupulous and ruthless behavior. His regiment would come to be known as the most extreme in terms of tactics, plundering and carrying out a “scorched earth” strategy. He took materials and supplies he needed and burned what he couldn’t use. His second-in-command was Lieutenant Colonel Daniel Read Anthony, brother of Susan B. Anthony.

Just because he was now a commissioned military officer didn’t prevent Jennison from continuing his unscrupulous and ruthless behavior. His regiment would come to be known as the most extreme in terms of tactics, plundering and carrying out a “scorched earth” strategy. He took materials and supplies he needed and burned what he couldn’t use. His second-in-command was Lieutenant Colonel Daniel Read Anthony, brother of Susan B. Anthony.

Colonel Jennison was giving the Union a bad name. Major General Henry Halleck complained to General George McClellan about the marauding jayhawkers of Jennison’s regiment:

The conduct of the forces under Lane and Jennison has done more for the enemy in this State than could have been accomplished by 20,000 of his own army. I receive almost daily complaints of outrages committed by these men in the name of the United States, and the evidence is so conclusive as to leave no doubt of their correctness.

Apparently Jennison’s ruthlessness was escalating when he was accused of attacking both sides indiscriminately:

J. W. Smith, clerk in the Department of the Interior, in Washington, is just in from the neighborhood of Rose Hill, and reports that Jennison’s men, under Major Anthony, are there committing depredations upon Union men and secessionists indiscriminately. They have burned forty-two houses in that vicinity and robbed others of valuables and driven off stock.

Mr. Smith says they took his wife’s silverware, furs, & c. He estimates the value of property taken from loyal citizens at $7,000; and, to cap the climax, they shot to death Mr. Richards, a good Union man, without cause or provocation.

Major General David Hunter issued orders on February 5, 1862, declaring martial law throughout the state of Kansas, in an effort to stop the practice of jayhawking. The law would be “enforced with vigor”:

. . . the crime of jaykawking shall be put down with a strong hand and by summary process; and for this purpose the trial of all prisoners charged with armed depredations against property or assaults upon life will be conducted before the military commissions . . .

Astonishingly, given Jennison’s reputation, he had been granted a promotion by Hunter to acting Brigadier General just days before on January 31. His command would expand to include not only the 7th Kansas Cavalry, but also the 8th Iowa Infantry and part of the 7th Missouri Voluntary Infantry, also known as the “Irish Seventh.” Then he was to be dispatched to New Mexico to fight Apaches, an obvious ploy I’m sure to send Jennison away to another post and hopefully put an end to jayhawking complaints. This enraged Jennison and he resigned on May 1, 1862. He didn’t go quietly, however.

He assembled the regiment and gave an impassioned farewell speech, citing the reasons for his resignation and excoriating Union commanders as being pro-slavery. He encouraged his regiment to continue to follow him in defending Kansas. An order was issued for his arrest for what was speculated to be “insubordination and exciting mutiny,” as reported by the Daily State Sentinel (Indianapolis). The Cedar Falls Gazette described his speech as “rather bitter on the powers that be.” In their estimation, “Jennison is a full-blooded Abolitionist.”

Although arrested and taken to St. Louis he never stood trial and was later released, returning to Kansas an anti-slavery hero. For a time he operated a freight hauling company, but after William Quantrill executed a devastating attack on Lawrence on August 21, 1863, Jennison was commissioned by Kansas Governor Thomas Carney to organize another cavalry regiment, later known as the Fifteenth. The Oskaloosa Independent (Kansas) was in wholehearted agreement: “Col. Jennison is going into Missouri at the head of the 15th regiment. Let him go.” All of Kansas seemed to be cheering him on:

He pursued Sterling Price in Missouri and led in battles at Lexington, Little Blue River, Westport and Newtonia. Apparently, though, he had returned to his marauding ways. In December of 1864 he was arrested, court-martialed, convicted and dishonorably discharged. He returned to Leavenworth, Kansas and was later elected to the Kansas Legislature and Senate. He died on June 21, 1884.

After Jennison resigned in 1862, the 7th Regiment’s New Mexico orders were rescinded and they instead were dispatched to Mississippi. Hopefully, the 7th Kansas Cavalry went on to fight more nobly.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Surname Saturday: Pillsbury

The Pillsbury surname is believed to have been emanated from an area in either Oxfordshire or Derbyshire, England. It is possibly a derivation of the Old English word “Pilsburg.” Broken down into its component parts: “pile” or “peel”, followed by “burgh” or “borough”. “Pile” or “peel” referred to a fortified farmhouse and “burgh” which often meant a place of security. One source indicates that the surname was possibly derived from the locational name Spelsbury, a village in Oxfordshire. The Old English word “speol” meant “watchful” and the Old English word “burh” meant “town” or “fortress.”

The 1086 Domesday Book lists a tenant by the name of “Pilesberie”. In the thirteenth century, mention was made of “Richard Pillsbury” in Derbyshire and in 1379 “Edward Pilsbury” is listed on the Yorkshire Poll Tax records. Besides “Pillsbury” and “Pilsbury”, other spelling variations of this surname include “Peelsbury”, “Pillsberry”, “Spelsbury” and “Spilsbury”, among others.

The 1086 Domesday Book lists a tenant by the name of “Pilesberie”. In the thirteenth century, mention was made of “Richard Pillsbury” in Derbyshire and in 1379 “Edward Pilsbury” is listed on the Yorkshire Poll Tax records. Besides “Pillsbury” and “Pilsbury”, other spelling variations of this surname include “Peelsbury”, “Pillsberry”, “Spelsbury” and “Spilsbury”, among others.

We are, of course, aware that the Pillsbury family made a name for themselves, for today the name is found in the baking section and dairy cases of practically every grocery store. One of the first Pillsbury immigrants, William, arrived in Dorchester, Massachusetts in 1640 or 1641. William is considered the common ancestor of all Pillsburys in America. His story follows, as well as that of Charles Alfred Pillsbury who co-founded the Pillsbury Company with his uncle John Sargent Pillsbury, and Parker Pillsbury, a minister and staunch defender of both abolition and women’s rights.

William Pillsbury

It is believed that William Pillsbury was born around 1605 in Staffordshire, England. While William Pillsbury immigrated to New England along with hundreds of other immigrants who were fleeing the tyranny of Charles I (1629-1640), it isn’t clear exactly what compelled him to make his voyage across the Atlantic. As the family history book, The Pillsbury family: being a history of William and Dorothy Pillsbury, records it:

He did not come with his Bible under his arm and his mouth full of phrases as to liberty of conscience, although he showed the true democratic spirit in after years, but he came “as the flying come, in silence and in fear.” The substance of the accounts is to the same effect, namely, that the young man felt obliged to flee is native land to escape the consequences of a misdemeanor, and on his arrival in Boston let himself as a servant to pay the expense of his passage.

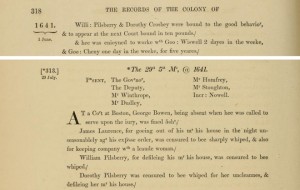

Not long after his arrival it appears he began courting Dorothy Crosbey and that he and Dorothy were sanctioned for some unseemly behavior on June 1, 1641 (click to enlarge):

It may or may not have been anything more than a trivial offense. As the Pillsbury family historian noted, “we must remember that this was about the time when it was said a Connecticut mother was punished for kissing her child on Sunday.” Sometime between the reprimand and July 29, 1641, when they were both censured to “bee whiped”, William Pillsbury and Dorothy Crosbey were married.

They likely remained in Dorchester for at least ten years since three (possibly four) of their children were born there. William and Dorothy had ten children who all lived to adulthood except their last child, Joshua, who died on his third birthday in 1674:

Deborah – 16 Apr 1642

Job – 16 Oct 1643

Moses – 1645

Abel – ?

Caleb – 28 Jan 1653

William – 27 Jul 1656

Experience – 10 Apr 1658

Increase – 10 Oct 1660

Thankful – 22 Apr 1662

Joshua – 20 Jun 1671 (died 20 Jun 1674)

Their son Increase died in 1690 along with three others who were on an expedition to Cape Breton, Nova Scotia.

Sometime in 1651 the Pillsbury family removed to Newbury, Massachusetts, where William purchased forty acres (including a house) for one hundred pounds. In the original deed, William Peelsbury, a yeoman of Dorchester, paid a down payment of fifteen pounds and the remainder in securities, probably from his holdings in Dorchester.

The remainder of their children were born in Newbury and the family attended the First Church in Newbury. On April 29, 1668, William Pillsbury was made a freeman. William is presumed to have been a man of wealth who increased his landholdings over the years, and also possessed at least one slave. On April 29, 1686, William “being sensible of my own morality & being of disposing mind & willing to set my House in order,” composed and signed his will in the presence of Tristram Coffin, less than two months before his death on June 19, 1686.

Parker Pillsbury

Parker Pillsbury was born in Hamilton, Essex County, Massachusetts on September 22, 1809 to parents Deacon Oliver and Anna (Smith) Pillsbury. He was their eldest child of eleven and Parker was named after his grandfather. Parker was a family name which likely appeared when William Pillsbury’s great-grandson Moses Pillsbury III married Mary Parker, parents of Parker Pillsbury the first.

Oliver Pillsbury, a deacon in his church, was an advocate of both temperance and abolition of slavery. The fervor he possessed was no doubt passed down to his son Parker, described in Men of Progress: Biographical Sketches and Portraits of Leaders in Business and Professional Life in and of the State of New Hampshire as:

. . . one of the heroes of New England’s famous “Abolition Trinity” (Garrison, Phillips, Pillsbury) and its last survivor, who for nearly half a century, in perils and hardships, devoted himself heart and soul to pleading the cause of the oppressed, denouncing iniquitous, superstitious, bigoted laws and practices, and demanding the removal of the yoke that held the colored race in cruel bondage . . .

Parker was educated in the local schools of Henniker, Massachusetts where his family had a farm, and, as would be the case in that day, he not only attended school but was expected to work on the family farm. Around the age of twenty he drove an express wagon from Lynn to Boston, but eventually returned to Henniker to farm. After becoming devoutly religious he was urged to pursue an education to prepare for ministry. He took the advice and pursued studies at the Andover Theological Seminary. In less than four years he was licensed to preach and took a pastorate in Loudon, New Hampshire. This, despite the fact that members of the seminary faculty had threatened to prevent him from leading a parish because of his anti-slavery beliefs.

He soon found, however, that his strong anti-slavery beliefs would not mesh well with the Christian Church, which at that time was known as “the bulwark of American slavery.” When he preached he denounced the practice in scathing terms – he called it the “sum of all villainies.” Since abolitionists weren’t popular he was forced to abandon his pulpit ministry in 1840. Instead he would become a “working apostle,” as Men of Progress described him.

He began lecturing and also took over the editorship of “Herald of Freedom” for a period of time. He later remarked that he entered “the lecture field with the full resolve to see the overthrow of the Southern slave system or perish in the conflict.” (Men of Progress, p. 220). On January 1, 1840 he had married Sarah H. Sargent, who not only supported his anti-slavery work but worked alongside him in his endeavors. The two were ostracized as evidenced by his decision to abandon pulpit ministry. They had only one child, Helen Buffum, born on June 14, 1843.

Parker and Sarah made their home in Concord, New Hampshire and worked tirelessly to abolish slavery. Although the Civil War was a tragic time, they must have been gratified by the outcome, and while they obtained heroic status among former slaves, they didn’t rest on their laurels. Following the Civil War, they both became involved in the Woman’s Suffrage movement, working alongside Mrs. Elizabeth Cady Stanton.

Still, their work in the anti-slavery movement is most remembered to this day. Parker chronicled the anti-slavery movement in his 1883 book, Acts of the Anti-Slavery Apostles. On July 7, 1898, “this reformer, hero, and honest man, left this world, which is the better for his having lived in it.” (Men of Progress, p. 222)

Charles Alfred Pillsbury

Charles Alfred Pillsbury was born on December 3, 1842 in Warner, New Hampshire, the oldest child of George Alfred and Margaret Sprague Carleton Pillsbury. A sister died in infancy and his brother Frederick Carelton was born in 1852. His father George had been modestly educated and was determined to be a successful businessman. His business interests steadily increased and he became well-respected for his integrity and business acumen, so much so he became one of the leading men of New Hampshire whose advice would be sought regarding important matters, according to Encyclopedia of Biography of Minnesota.

Charles was raised in a modest home and attended public school. He graduated from Dartmouth in 1863 and moved to Montreal to clerk for Buck, Robinson and Co., a produce commission company. During this time, he met Mary Ann Stinson, marrying her on September 12, 1866. Their first two children, George Alfred (1871-1872) and Margaret Carleton (1876-1881) died at young ages. On December 8, 1878 twin sons, Charles Stinson and John Sargent II, were born.

After three years Charles bought into the company and remained there until 1869 when he sold out to join his uncle, John Sargent Pillsbury, in a Minneapolis business venture. The two men pooled their money and purchased a struggling flour mill. The purchase was generally viewed as a mistake since flour milling was not a particularly lucrative business at that time, and neither of the Pillsburys knew anything about the flour milling business.

After three years Charles bought into the company and remained there until 1869 when he sold out to join his uncle, John Sargent Pillsbury, in a Minneapolis business venture. The two men pooled their money and purchased a struggling flour mill. The purchase was generally viewed as a mistake since flour milling was not a particularly lucrative business at that time, and neither of the Pillsburys knew anything about the flour milling business.

Nevertheless, Charles skillfully guided the company and three years later it began to show a profit, prompting a name change: Charles A. Pillsbury and Co. With Charles at the helm, the company flourished. He had an eye for technology and brought in the latest equipment available at the time. For instance, mill operations were powered by water from the nearby Falls of St. Anthony, producing two hundred barrels of flour a day. Purifiers were installed to produce fine white flour and his mill was the first in America to use steam rollers rather than burr stones to crush the grain.

By 1872 his father George and brother Frederick had joined him. In 1876 Uncle John became the governor of Minnesota. The family business continued to grow after acquiring four more mills. In 1881 they built the largest flour mill in the world. Innovation was always on Charles’ mind. His travels throughout Europe had brought the steam roller and purifier technology to his mills.

Disaster struck in 1881, however, when three of their mills were destroyed by fire. They rebuilt the mills and by 1889 the mills were producing over ten thousand barrels of flour every day. Charles paid his workers well and shared the company’s profits at year’s end with his employees.

During the 1880’s wheat and flour prices were depressed and competition increased. In a decision influenced by their desire to expand into the British market, and ultimately worldwide, the Pillsburys allowed a British consortium to purchase a controlling interest in the company. The new company name would be Pillsbury-Washburn Company, Ltd., the largest flour milling company in the world. The Pillsbury family still retained significant stock in the company and Charles was the managing director. With a means to market his products internationally, he was instrumental in making “Pillsbury’s Best” a recognizable, worldwide trade name. The rest, as they say, is history.

Charles Alfred Pillsbury died on September 17, 1899 at the age of fifty-six. The Pillsbury family re-acquired the company in 1923, selling it again in 1989. The brand is now owned by General Mills.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

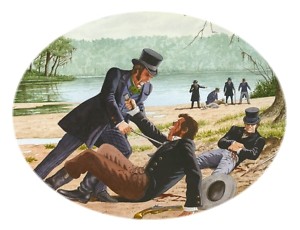

Feudin’ and Fightin’ Friday: Battle at the Sandbar

This “battle” only lasted about ten minutes, and perhaps only receiving historical mention because from it emerged the legend of James “Jim” Bowie, expert knife-fighter, who less than a decade later famously perished at the Battle of the Alamo.

This “battle” only lasted about ten minutes, and perhaps only receiving historical mention because from it emerged the legend of James “Jim” Bowie, expert knife-fighter, who less than a decade later famously perished at the Battle of the Alamo.

James Bowie was born in Kentucky in 1796, the son of Rezin and Elve Ap-Catesby (Jones) Bowie. By 1801 his family had migrated to Rapides, Louisiana and sworn allegiance to the Spanish government. During his teen years, James hauled lumber down the river to market. Fond of fishing and hunting, it is said that he also rode wild horses and alligators (maybe more legend than fact). James and his brother Rezin decided to join Andrew Jackson’s forces during the War of 1812, but soon after their decision to join the war had officially ended.

After the war James and his brother were involved in the slave trade. Bowie would purchase slaves from the pirate Jean Lafitte and then sell them in St. Landry Parish. When they had accumulated a fortune of $65,000, they exited the slave trade business and turned to land speculation, making friends with local wealthy plantation owners.

After the war James and his brother were involved in the slave trade. Bowie would purchase slaves from the pirate Jean Lafitte and then sell them in St. Landry Parish. When they had accumulated a fortune of $65,000, they exited the slave trade business and turned to land speculation, making friends with local wealthy plantation owners.

When James applied for a loan from the local bank, he was turned down. Major Norris Wright was a bank director and neighbor of the Bowies, and said to have been responsible for blocking the loan. Their relationship was contentious at times – the Bowies had once opposed him in a sheriff’s election, supporting Wright’s opponent. When the two men met unexpectedly in Alexandria, Wright shot Bowie point-blank — although the bullet was deflected, some say by a silver dollar in his pocket. Bowie’s gun misfired (or perhaps he was unarmed) so he wasn’t able to defend himself. Legend has it that Rezin then gave James a large butcher-type knife to carry for his protection so he would never be without a means to defend himself. Later the knife would be called a “Bowie Knife,” especially after the incident that happened the following year.

Two men, Samuel Levi Wells III and Dr. Thomas Maddox, had challenged each other to a duel. The face-off was to be held on a sandbar just north of Natchez, Mississippi on September 19, 1827. Samuel Wells later gave his own account:

I was invited by Dr. Maddox, not long since, to an interview without the limits of the state, I met him at Natchez, on the 18th inst. and on the 18th I was challenged by him. I appointed the 19th for the day, and the first sand beach above Natchez, on the Mississippi side, for the place of meeting. We met, exchanged two shots without effect, and made friends.

Wells and his friend Major George McWhorter and Wells’ surgeon, Dr. Cuney (everyone needs to have their surgeon present at a duel!) were invited by Dr. Maddox and his friend Colonel Crain and surgeon Dr. Cuney to the woods where other friends, excluded from the dueling field, had stationed themselves. As they were walking over to the area where they would partake of “after-dueling refreshments,” they were met by General Cuney, James Bowie and Thomas Jefferson Wells, Samuel’s brother.

General Cuney inquired as to how the affair had been settled and Wells told him that he and Dr. Maddox had “exchanged two shots and made friends.” Wells continued his version of the events:

He [General Cuney] turned to Colonel Crane [sic] who was near me, and observed to him that there was a difference between them, and that they had better return to the ground & settle it as Dr. Maddox and myself had done. Dr. Cuney and myself interposed and stated to the General that that was not the time nor the place for the adjustment of their difference; the General immediately acquiesced; and his brother had turned to leave him, when Crane [sic], without replying to General Cuney, or saying one word fired a pistol at him, which he carried in his hand, but without effect. I then stepped back one or two paces, when Crane [sic] drew from his belt another pistol, fired at and wounded Gen. Cuney in the thigh; he expired in about fifteen minutes.

Apparently Colonel Crain had pre-meditatively planned the confrontation with Cuney. Crain had been overheard earlier telling friends in Natchez that if the General made an appearance at the duel he intended to kill him, and as Wells puts it, “and well has he kept his promise.” A man referred to only as “Dr. Hunt” had tried to warn Cuney the night before but was unable to locate him.

After Crain killed Cuney, he drew his gun, fired and wounded Bowie in the hip. Bowie drew his knife and rushed Crain. However, Crain struck Bowie’s head with his empty pistol, bringing Bowie to his knees, breaking the pistol. Virgil E. Baugh, author of Rendevous at the Alamo: Highlights in the Lives of Bowie, Crockett, and Travis, provides the rest of the story, taken from the recollections of a Bowie family historian and a Southern newspaper article:

Before [Crain] could recover he was seized by Dr. Maddox who held him down for some moments, but, collecting his strength, he hurled Maddox off just as Major Wright approached and fired at the wounded Bowie, who, steadying himself against a log, half buried in the sand, fired at Wright, the ball passing through the latter’s body. Wright then drew a sword-cane, and rushing upon Bowie, exclaimed, “Damn you, you have killed me.” Bowie met the attack, and seizing his assailant, plunged his “bowie-knife” into his body, killing him instantly. At the same moment Edward Blanchard shot Bowie in the body, but had his arm shattered by a ball from [Thomas] Jefferson Wells.

The aftermath of the “fight at the duel”: Major Wright and General Cuney killed; Bowie, Crain and Blanchard badly wounded. According to the family historian, Colonel Crain brought water for Bowie. Bowie “politely thanked him, but remarked that he did not think Crain had acted properly in firing upon him when he was exchanging shots with Maddox. In later years Bowie and Crain became reconciled, and, each having great respect for the other, remained friends until death.”

Bowie was taken away and presumed to have been mortally wounded – but Bowie recovered. What would also become legendary was Bowie’s ability to survive. The earliest news articles (even though published weeks after the actual incident) were reporting that Bowie was not expected to survive. But survive he did to fight another day.

Bowie was taken away and presumed to have been mortally wounded – but Bowie recovered. What would also become legendary was Bowie’s ability to survive. The earliest news articles (even though published weeks after the actual incident) were reporting that Bowie was not expected to survive. But survive he did to fight another day.

Witnesses began to spread the word of Bowie’s knife skills – they all remembered Bowie’s “big butcher knife.” Thus began the legend of Jim Bowie and his formidable knife-fighting skills. Thereafter, newspaper articles written about fights and disputes would often make mention of a “Bowie Knife.” A blacksmith by the name of James Black made the first official Bowie Knife for Bowie in 1830. After Jim Bowie’s death at the Alamo in 1836, Black did a brisk business selling the knives to pioneers headed to Texas.

The “Battle of the Sandbar” wasn’t the last duel/fight that Jim Bowie would be involved in. In 1829 he tangled with John “Bloody” Sturdivant in Natchez. He had traveled to Natchez to help the son of a family friend, Dr. William Lattimore. The son had been duped by Sturdivant in a crooked faro game and Bowie was there to help even the score. Bowie, although not an expert card player, was able to win back the son’s losses.

Sturdivant was bragging that had he been at the Sandbar duel he would have made sure Bowie had died that day. When Bowie returned to respond to Sturdivant’s threats, he was challenged to a knife fight with these rules: the two men would have their left hands tied together across a table. Bowie accepted the terms and swiftly knifed his opponent’s right arm. Although not mortally wounded, Bowie had made his point with Sturdivant. According to Rendevous at the Alamo, Sturdivant hired three assassins to hunt down and kill Bowie. Although no official accounts remain, it is said that Bowie killed all three men “in his first fight using Black’s knife.”

Bowie knives are still made today and sold ubiquitously, even at Walmart, where they are advertised as: “This Winchester Large Bowie Knife is a gargantuan, multi-purpose tool that will come in handy in nearly any situation. Its beefy 8.75″ fixed blade is made from stainless steel, so it is durable and dependable.”

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

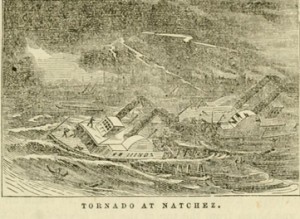

Wild Weather Wednesday: The Great Natchez Tornado of 1840

On May 7, 1840 a massive tornado tore through Natchez, Mississippi. Just the night before the area on both sides of the river, Concordia Parish in Louisiana and Adams County in Mississippi, were drenched with over three inches of rain. With all the rain in the area, farmers wouldn’t be planting that day. Nevertheless, the area around Natchez and Vidalia (across the river on the Louisiana side) hummed with activity.

On May 7, 1840 a massive tornado tore through Natchez, Mississippi. Just the night before the area on both sides of the river, Concordia Parish in Louisiana and Adams County in Mississippi, were drenched with over three inches of rain. With all the rain in the area, farmers wouldn’t be planting that day. Nevertheless, the area around Natchez and Vidalia (across the river on the Louisiana side) hummed with activity.

Historically, southwestern Mississippi had been inhabited by Natchez Indians, perhaps as early as A.D. 700 until the 1730’s. Fort Rosalie was established by the French in 1716. With a fort to provide protection from the Indians, permanent settlements began to spring up around the area. There were, of course, conflicts with the Indians, primarily over land use and resources.

On November 29, 1729 the Natchez tribe, joined by the Chickasaw and Yazoo tribes, attacked Fort Rosalie in what came to be known as the “Natchez Massacre.” Over two hundred French colonists were killed that day and the Natchez seized Fort Rosalie. The French retaliated by massacring an entire village of Chaouacha – a group who had nothing to do with the attack on Fort Rosalie. The French, along with Choctaw allies, began a campaign to conquer the Natchez who were then sold into slavery. By the mid-to-late 1730’s the Natchez had been driven away and forced to live with other tribes.

The Spanish and British had a presence in the area, and after the Revolutionary War British claims were ceded to the United States under the terms of the 1793 Treaty of Paris. The Spanish still maintained at least some control until the 1795 Treaty of San Lorenzo, although it took over two years for the Spanish forces around Natchez to receive word. Their surrender came on March 30, 1798 and a week later Natchez was designated as the first capital of Mississippi Territory.

The Spanish and British had a presence in the area, and after the Revolutionary War British claims were ceded to the United States under the terms of the 1793 Treaty of Paris. The Spanish still maintained at least some control until the 1795 Treaty of San Lorenzo, although it took over two years for the Spanish forces around Natchez to receive word. Their surrender came on March 30, 1798 and a week later Natchez was designated as the first capital of Mississippi Territory.

Although the capital was eventually moved to Jackson, Natchez continued to grow and develop into a hub of economic activity, especially the exportation of cotton. The town’s strategic location on the Mississippi River allowed local plantation owners to have their cotton loaded on steamboats at Natchez-Under-The-Hill for transport either downriver to New Orleans or upriver to St. Louis and beyond. Natchez had a burgeoning slave trade market which also contributed to the area’s economy.

On May 7, 1840 there were scores of boats assembled under-the-hill – steamboats, flat boats, skiffs – not just for cotton export but to trade produce and other goods. Just after noon that day a severe thunderstorm moved through the area, accompanied by another round of drenching rain. Simultaneously, about twenty miles southwest of Natchez, a tornado was forming and headed northeast toward the Natchez-Vidalia area.

The tornado roared along the Mississippi, stripping forests and vegetation on both shores. When the tornado reached Natchez Landing, flat boats were tossed into the river, drowning both crew and passengers. Other boats were tossed onto land and those unfortunate enough to be working along the landing area were also killed. Accuweather.com notes that this was the only tornado in United States history where more people were killed than injured – at least 317 were killed and 109 injured.

Some historians believe the death toll was underestimated since during that period of history slaves were possibly not counted. The Natchez Free Trader headlined the tragic event as “Dreadful Visitation of Providence”. The story was picked up by other newspapers, but in many cases news did not reach the rest of the country for days, even weeks afterwards. The Pittsburgh Gazette finally mentioned the devastating storm on May 20 – almost two weeks after the event, and long before the era of “yellow journalism” when headlines would have “screamed” in massive ALL CAPS sensationalism. Oh what a difference one hundred and seventy-four years makes!

Some historians believe the death toll was underestimated since during that period of history slaves were possibly not counted. The Natchez Free Trader headlined the tragic event as “Dreadful Visitation of Providence”. The story was picked up by other newspapers, but in many cases news did not reach the rest of the country for days, even weeks afterwards. The Pittsburgh Gazette finally mentioned the devastating storm on May 20 – almost two weeks after the event, and long before the era of “yellow journalism” when headlines would have “screamed” in massive ALL CAPS sensationalism. Oh what a difference one hundred and seventy-four years makes!

The Free Reader dramatically described the tornado and its aftermath:

About 1 o’clock on Thursday, the 7th inst, the attention of the citizens of Natchez were attracted by an [un]usual and continuous roar of thunder to the southward, at which point hung masses of black clouds, some of them stationary, and others whirling along with under currents, but all driving a little east of north. As there was evidently much lightning, the continual roar of growling thunder, although noticed and spoken of by many, created no particular alarm.

The dinner bells in the large hotels had rung, a little before 2 o’clock, and most of our citizens were sitting at their tables, when, suddenly, the atmosphere was darkened, so as to require the lighting of candles, and in a few moments afterwards, the rain was precipitated in tremendous cataracts rather than drops. In another moment the tornado, in all its wrath, was upon us. The strongest buildings shook as if tossed by an earthquake; the air was black with whirling eddies of house walls, roofs, chimnies [sic], huge timbers torn from distant ruins, all shot through the air as if thrown by some mighty catapult. . . The greater part of the ruin was effected in the short space of 3 to 5 minutes, although the heavy sweeping tornado lasted nearly half an hour. For about five minutes it was more like the explosive force of gunpowder than any thing else it could have been compared to. Hundreds of rooms were burst open as sudden as if barrels of gunpowder had been ignited in each.

Lloyd’s Steamboat Directory, published in 1856, chronicled “Disasters on the Western Waters” and included a story about the Natchez tornado. Although there were always several boats docked in Natchez at any one time, the Steamboat Directory especially noted that: “A tax had recently been laid on flat-boats at Vicksburg, on which account many of them had dropped down to Natchez, so that there was an unusually large number of these boats collected at the last-named city at the time of the tornado.”

The steamboat Hinds was blown into the river and sunk, and all crew members and passengers, except four men, were lost. The Hinds was swept all the way down to Baton Rouge, where it was later found with fifty-one dead bodies – forty-eight males and three females, one of them being a three-year old girl. The steamboat Prairie had just pulled in from St. Louis carrying a shipment of lead. Everything above the deck was swept off and all crew and passengers presumed to have perished. One other steamboat, the H. Lawrence, was sheltered somewhat and although severely damaged was not sunk. One boat, the Mississippian, used as a floating hotel and grocery store, was sunk. Of the one hundred and twenty flat boats at the landing that day, all but four were lost and most of the men who operated them were killed, possibly as many as two hundred.

The Steamboat Directory provided this historical account:

For its violence and destructive effects, this tornado was without precedent in the recollection of the oldest inhabitant of that region. The water in the river was agitated to that degree that the best swimmers could not sustain themselves on the surface. The waves rose to the height of ten or fifteen feet. Many houses in the vicinity of Natchez were blown down, and many buildings in the city were unroofed; the roofs, in some instances, being carried half-way across the river. People found it impossible to stand on the shore. One man was blown from the top of the hill (sixty feet high) and well into the river forty yards from the bank. Heavy beams of timber and other ponderous objects were blown about like straws. Great was the consternation of the inhabitants of Natchez and its neighborhood, and owing to this cause, perhaps, many persons were drowned for want of prompt assistance.

The storm was thought to have been approximately two miles in width since devastation was also seen across the river in Vidalia. While the devastation was immense down at Natchez-Under-the-Hill, the upper part of the city also suffered great damage – hardly a house escaped damage or complete ruin. Homes, hotels and churches were missing roofs or leveled altogether. The Vidalia Court House was “utterly torn down.” While there were many injuries in Vidalia, there was only one fatality. Parish Judge G.W. Keeton was instantly killed while dining with a fellow attorney.