Far-Out Friday: Friggatriskaidekaphobia and the Thirteen Club

Do you suffer from friggatriskaidekaphobia (and you say, I don’t even know how to pronounce it, so how could I be afflicted with it!?!). Maybe not, but it may affect between seventeen and twenty million Americans. According to the Mayo Clinic, in clinical terms a phobia “is an overwhelming and unreasonable fear of an object or situation that poses little real danger but provokes anxiety and avoidance.”

Do you suffer from friggatriskaidekaphobia (and you say, I don’t even know how to pronounce it, so how could I be afflicted with it!?!). Maybe not, but it may affect between seventeen and twenty million Americans. According to the Mayo Clinic, in clinical terms a phobia “is an overwhelming and unreasonable fear of an object or situation that poses little real danger but provokes anxiety and avoidance.”

This particular phobia, as it relates to a certain calendar date, may only be experienced one to three times per year. This year it will haunt millions of people three times on a Friday – February 13, March 13 and November 13 – and no one seems to know definitively when and where the notion of “Friday the 13th” being an unlucky day, or for that matter the number “13″ being associated with misfortune and bad luck, originated.

This particular phobia, as it relates to a certain calendar date, may only be experienced one to three times per year. This year it will haunt millions of people three times on a Friday – February 13, March 13 and November 13 – and no one seems to know definitively when and where the notion of “Friday the 13th” being an unlucky day, or for that matter the number “13″ being associated with misfortune and bad luck, originated.

This article has been removed from the web site, but will be rewritten, complete with footnotes and sources, and included in the September-October 2019 issue of Digging History Magazine.

This article has been removed from the web site, but will be rewritten, complete with footnotes and sources, and included in the September-October 2019 issue of Digging History Magazine.

I invite you to check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads, just carefully-researched stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? That’s easy if you have a minute or two. Here are the options (choose one):

- Scroll up to the upper right-hand corner of this page, provide your email to subscribe to the blog and a free issue will soon be on its way to your inbox.

- A free article index of issues is available in the magazine store, providing a brief synopsis of every article published in 2018. Note: You will have to create an account to obtain the free index (don’t worry — it’s easy!).

- Contact me directly and request either a free issue and/or the free article index. Happy to provide!

Thanks for stopping by!

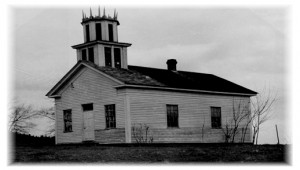

Ghost Town Wednesday: Claquato, Washington

Lewis Hawkins Davis left Indiana in 1851 and joined a wagon train in Independence, Missouri, heading west to Oregon Territory’s Willamette Valley. Two years after arriving he headed north to Saunders Bottom in Lewis County, Washington where he built a double log cabin for his family. His son Levi Adrian Davis filed a claim for adjoining property. Upon arrival they remained a few days with the Saunders family, their nearest neighbors, while scouting the area for land.

Lewis Hawkins Davis left Indiana in 1851 and joined a wagon train in Independence, Missouri, heading west to Oregon Territory’s Willamette Valley. Two years after arriving he headed north to Saunders Bottom in Lewis County, Washington where he built a double log cabin for his family. His son Levi Adrian Davis filed a claim for adjoining property. Upon arrival they remained a few days with the Saunders family, their nearest neighbors, while scouting the area for land.

The Davis family settled on a hillside in an area the Indians called Claquato (pronounced Cla-kwah-toh, the name means “high ground” in Salish). The next order of business for Lewis, with the help of other settlers, was a road-building program, and all roads led to his home on the hill. The first road went over the hill and down into the Chehalis Valley to the place where the Skookumchuck River emptied into the Chehalis River, a place where Lewis encouraged new settlers to camp upon arrival.

The Davis family settled on a hillside in an area the Indians called Claquato (pronounced Cla-kwah-toh, the name means “high ground” in Salish). The next order of business for Lewis, with the help of other settlers, was a road-building program, and all roads led to his home on the hill. The first road went over the hill and down into the Chehalis Valley to the place where the Skookumchuck River emptied into the Chehalis River, a place where Lewis encouraged new settlers to camp upon arrival.

Lewis County was created on December 19, 1845 (originally named after George Vancouver) when Washington Territory was carved out of Oregon Territory. In 1849 the county was renamed after explorer Merriwether Lewis.

As was the case all across the West in the years encompassing the era known as “Manifest Destiny”, Indians viewed the white man’s intrusion on their lands with suspicion and distrust. And, of course, the better the roads, the more people came. In 1853 military roads were built, Olympia became the state capital and California 49’ers whose fortunes didn’t quite pan out headed to claim free land in Washington Territory.

Lewis Davis took advantage of the influx of settlers by offering lodging with meals and corrals for their horses and stock. The United States government began constructing stockades to protect settlers in 1855 and Davis obtained a contract, provided workers and his wife cooked for them. When the Indian troubles began several families moved to the safety of the stockade, but with only one hundred square feet of space some found it too confining and decided to take their chances.

However, not all of the Indians in the area were unfriendly. According to Chehalis by Julie McDonald Zander, a friendly Chehalis Indian by the name of John Heyton rode through the night to warn settlers when Indians were about to attack. When the Saunders family returned to their homestead in 1856 after the threats passed, they found their house, barn and fences burned, their stock killed and everything destroyed or stolen.

The Saunders family was forced to start over. According to Zander, the Cowlitz and Chehalis Indians were friendly with Schuyler Saunders. He preached the gospel and sang hymns and the natives called him “King George’s Man”.

In 1857 Davis built a whipsaw-type sawmill near where Mill Creek emptied into the Chehalis River. The first lumber produced was donated for construction of the Claquato Church. The church was built in 1858, one that still stands today as the oldest building in Washington. The inside was furnished with pews and a pulpit donated by the nearby community of Boistfort, an organ purchased by subscription, and a bronze bell shipped from Boston by boat around Cape Horn. The church’s belfry was unique – “a triple decker with a louvered square on the bottom, a smaller louvered octagon in the middle, and a symbolic crown of thorns on top” (The Daily Chronicle, Centralia, Washington; 10 May 1969).

Because all of the furnishings, the land, materials and labor had been donated, the church opened its doors debt-free. On May 7, 1859, Lewis Davis and his wife Susan officially deeded the land at the corner of Military and Church Streets to the Methodist Episcopal Church, stipulating that the church must be available as a school facility for a period of seven years. The church’s first pastor, John Harwood, was also the first teacher at Claquato Academy.

Because all of the furnishings, the land, materials and labor had been donated, the church opened its doors debt-free. On May 7, 1859, Lewis Davis and his wife Susan officially deeded the land at the corner of Military and Church Streets to the Methodist Episcopal Church, stipulating that the church must be available as a school facility for a period of seven years. The church’s first pastor, John Harwood, was also the first teacher at Claquato Academy.

The town continued to prosper and grow under Davis’ leadership. Claquato thrived as a way station with hotels and other shops to accommodate travelers as well as local residents. The Davis Prairie post office was established on May 10, 1858 and renamed the Claquato post office on September 15 of that year. In 1862 the courthouse was completed after the state legislature agreed to designate Claquato as the county seat if Davis would donate the land and provide the materials.

In 1864 the town had fifty residents, but that same year lost its founder. Lewis Davis died from injuries sustained in a fall at his sawmill. Towns like Claquato with its growing lumber industry needed railroads to continue to thrive, but when the Northern Pacific Railroad bypassed Claquato in 1874, Claquato lost the county seat on July 4 as residents gradually moved to the new county seat of Saundersville (later renamed Chehalis, and still the county seat today).

On August 6, 1902 the town of Claquato was officially vacated. The church, of course, remains and was used for Sunday School and occasional services until the mid-1930’s. The building had deteriorated, and after a time the Lewis County Commission undertook steps to restore it. In 1973 it was added to the National Register of Historic Places. The large cemetery, started in 1856, is still utilized and maintained.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Tombstone Tuesday: Ambrose Hill and Callie Donia Fickling Bradshaw

Ambrose Hill and Callie Donia Fickling Bradshaw were married on March 6, 1918. For both it was a second marriage – Ambrose was a widower and Callie Donia divorced with five children. A few things intrigued me about this couple: their names, their large blended family and their faith.

Ambrose Hill and Callie Donia Fickling Bradshaw were married on March 6, 1918. For both it was a second marriage – Ambrose was a widower and Callie Donia divorced with five children. A few things intrigued me about this couple: their names, their large blended family and their faith.

Ambrose Hill Bradshaw

Ambrose Hill Bradshaw was born on January 29, 1867 in Alexander County, North Carolina to parents John Sloan and Mary Louise (Barker) Bradshaw. John was a Confederate who volunteered on November 2, 1861 and was mustered in on December 31. He was wounded on August 29, 1862 at Manassas and later at Chancellorsville the following year. John and Mary remained in North Carolina but Ambrose migrated to Tennessee sometime after the 1880 census, although the date is unclear with no 1890 census records available.

Ambrose married Beulah Mae Corpier in Giles County, Tennessee on March 20, 1894 and daughter Leafy was born in June 1894 according to the 1900 census. By 1910 Ambrose and Beulah were residing in Hill County, Texas with eight children, ranging in ages from 15 to 1: Leafy, Clayton, Bert, Minnie, Colonel, Mary, Florence and Floyd.

On February 19, 1914 Beulah Mae died of cancer in Hood County, Texas, leaving Ambrose to raise his young children. He married Caledonia (or “Callie Donia”) Fickling Osborn on March 6, 1918 in Young County, Texas. According to his obituary, Ambrose had relocated his family to Young County around 1916 and later operated a dry goods and mercantile store on the eastern edge of Proffitt. Census records indicate that he was also a farmer.

Callie Donia had five children from her first marriage: William Terrell, Ethel Irene, Edgar Franklin, Josie May and Bishop Marvin (daughter Mollie, born in 1911, died in 1912). Together Ambrose and Callie Donia had three children of their own: Viola Pearl, Ambrose Ray and Dick Worth.

Callie Donia had five children from her first marriage: William Terrell, Ethel Irene, Edgar Franklin, Josie May and Bishop Marvin (daughter Mollie, born in 1911, died in 1912). Together Ambrose and Callie Donia had three children of their own: Viola Pearl, Ambrose Ray and Dick Worth.

I say “at least” because there are two accounts of Ambrose Ray Bradshaw’s obituary, one indicating that he had sixteen siblings (some half-siblings) and the other account from a niece indicating he had two siblings and twenty half-siblings.

Ambrose, known as “A.H.”, was eighteen years older than Callie Donia and died at the age of seventy-four on November 21, 1941 from pneumonia. At the time of his death, he was survived by his wife, six sons and four daughters. His parents had died in North Carolina in the 1910’s. Using census records, to the best of my calculations, it appears that together he had sixteen children and stepchildren – eight from his first marriage, five from Callie Donia’s first marriage and three of their own.

Callie Donia Fickling

Callie Donia Fickling (some family historians believe her actual name was Caledonia) was born on March 7, 1885 in Young County to parents Robert Glasgow and Malinda Louise (Rogers) Fickling. Her parents were both born in Alabama and in 1900 Callie Donia was the second oldest of eleven children.

On October 16, 1904 she married John Franklin Osborn and together they had at least six children it appears. As noted above they were William Terrell, Ethel Irene, Edgar Franklin, Josie May and Bishop Marvin. Mollie, born in 1911, died in 1912. It is unclear when Frank and Callie Donia divorced or whether he remarried (his death certificate in 1949 stated he was divorced and son W.T. was the contact).

On October 16, 1904 she married John Franklin Osborn and together they had at least six children it appears. As noted above they were William Terrell, Ethel Irene, Edgar Franklin, Josie May and Bishop Marvin. Mollie, born in 1911, died in 1912. It is unclear when Frank and Callie Donia divorced or whether he remarried (his death certificate in 1949 stated he was divorced and son W.T. was the contact).

An aside: Some family trees indicate that Callie Donia married a third time on June 1, 1947 to George Thomas Collier, but there don’t seem to be any facts to back that up. That, in addition to the fact that the George they refer to died in Sevier County, Arkansas in 1952 and there is no mention of Callie Donia.

Callie Donia was a homemaker who moved to Olney in 1967. She was a member of the Assembly of God Church and her son Ambrose Ray, also a member of the denomination, had served in World War II and later attended Southwestern Assemblies of God College (now University) in Waxahachie, Texas. This was of interest to me since I attended college there as well.

At the time of her death on October 6, 1974 at the age of eighty-nine, Callie Donia Fickling Osborn Bradshaw was survived by three daughters and five sons. She was buried next to Ambrose in Proffitt Cemetery.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Surname Saturday: Cakebread

This unusual name is among the oldest known surnames, possibly of Norse-Viking and Olde English pre-ninth century origins, according to The Internet Surname Database. The name may have been derived from a combination of a Norse word, “kaka” (meaning cake) and the English word “brede”.

Since many of the early surnames reflected a certain profession, it’s likely Cakebread was an occupational name for someone who was a baker of fancy bread. These were probably dainty cakes and small flat loaves, made of an especially fine and sweet flour called “cakebread”. A similar name of French origins, Blanchpain, would also indicate someone who was some sort of specialty baker.

In 1109 Canterbury records mention Aedwinus Cacabread during the reign of King Henry I; in 1210 Alred Cake appeared on the pipe rolls of Norfolk; John le Kakier appeared on a1929 London record; Richard Cakebread was listed on the Subsidy Rolls of Suffolk in 1327.

In 1109 Canterbury records mention Aedwinus Cacabread during the reign of King Henry I; in 1210 Alred Cake appeared on the pipe rolls of Norfolk; John le Kakier appeared on a1929 London record; Richard Cakebread was listed on the Subsidy Rolls of Suffolk in 1327.

Spelling variations include Cakebread, Cacabred, Cakebred, Cacabread, Cakbred and Cakebrede, although since the fourteenth century the spelling has been fairly consistent as “Cakebread.”

Among the first Cakebreads to immigrate to America were Thomas and Sarah (Busby) Cakebread. They are listed on a passenger list of the Winthrop Fleet, a group of eleven ships led by John Winthrop, who brought approximately one thousand Puritans to New England in the summer of 1630. Thomas died in 1642 and Sarah married John Grout in 1643.

Jane Cakebread

The most infamous Cakebread who ever lived had to have been an English woman named Jane Cakebread:

The Los Angeles Herald published an obituary of sorts for Jane on December 18, 1898:

Jane Cakebread, for years a figure in the London police courts, is dead. She held the record for convictions for drunkenness or disorderly conduct, having been found guilty of these offenses about three hundred times.

Jane Cakebread was an extremely interesting old woman – to study. Physicians and those who teach temperance in strong drink finally decided that she was drunken because she liked drunkenness. The police agreed with them. When she was drunk she was violent and vicious; when she was sober, she was very repentant, and so remained until she got drunk again.

She was fifty-seven years old, so it is debatable if the habitual use of alcohol internally shortened her life. Forty years ago she went from her home in Hartfordshire to London and became a parlor maid – and a smart one. In forty years are 480 months. It is fair to presume that Jane suffered on an average a fortnight’s imprisonment on each of her 300 convictions; 150 months’ imprisonment in all. So in forty years in London she was in the lock-up twelve years and a half, and free – drunk or repentant – twenty-sever years and a half.

There is a tradition that Jane Cakebread was very handsome when young, but of late years, whatever her capacity as a professional drunkard, she could not have posed as a professional beauty.

Her chief claim to true fame must always be that she was the prime cause of Lady Henry Somerset’s libel suit for $25,000 damages against William Waldorf Astor. Lady Henry Somerset, as every one should know, is a wonderful and sincere advocate of temperance in strong drink. Lady Henry studied Jane Cakebread and decided that she was not bad at heart, nor cruel, had never willfully harmed anybody but herself. To rescue a brand from the burning Lady Henry induced Jane to enter the temperance home on her ladyship’s Redhill estate, four miles from a saloon. In a few days Jane had turned the home into a pandemonium, and at the end of three weeks Lady Henry turned her out as utterly unmanageable and because she corrupted other inmates.

A few days later Jane was again in a police court, and at Lady Henry’s suggestion was examined as to her sanity. The physician certified that she was irresponsible, and as a preliminary step she was sent to the Hackney Infirmary. There the old woman, who was not bad at heart, nor cruel, kicked the medical officer, Dr. Gordon, in the ribs. Soon the doctor became ill and two of his ribs proved to be broken. On the Bowery they would have said “Jane kicked in his slats.”

The Pall Mall Gazette was impolite enough to say repeatedly that Jane Cakebread’s madness was caused by association with Lady Henry Somerset. William Waldorf Astor was asked to withdraw these remarks and apologize. He not only refuse to do either, but when Lady Henry began suit for libel, dared to assert justification as his defense, declaring in effect that Lady Henry and her associates by their methods or furthering intemperance, would drive nearly anybody mad.

The best lawyers in London were engaged by the parties to the suit, but it was settled out of court. Mr. Astor apologized to Lady Henry, and the Pall Mall Gazette and twenty other papers paid the costs. Now the tipsy Jane who provoked the suit is gone.

Another obituary headline called her an “Aged Inebriate”, believing her to be seventy years old. Jane had made her escape from the home after “she had hemmed one hundred and twenty towles, eighteen table cloths, and made a quantity of children’s clothing”, walking in stages back to London, “where she immediately began to make up for her prolonged abstinence. When arraigned for her two hundred and eighty-fifty time, she was in a condition that the police officers described as ‘hilariously drunk.’”

Jane hadn’t been too keen on the idea of going to Lady Henry’s temperance home in the first place:

I means on offense, but I’m not going to no ‘ome – not I, at present, anyhow. “Oh, it’s not an ‘ome at all,” they says, and I’ll do just what I likes, and perhaps that’s so; but I’m going to my own friends, I am.

A prison missionary had tried to help her once and concluded that she had been “misjudged.” He pointed out that Jane had never been arrested for being “drunk and incapable”, but rather for “disorderly conduct.” The missionary declared that one little drop of drink “drove the woman demented.” Articles and essays have been written about her, but most concluded she was beyond help. She was said to have been the reason the Inebriates Act of 1898 was passed, wherein special homes were to be provided for habitual drunkards.

A record of the London police courts indicates that when imprisoned she would sing her favorite hymns or recite portions of the Bible. Her memory was sharp; she could quote two chapters from the Book of Job. She prayed on her knees, only to rise from those prayers and spew obscenities. Clearly she was insane.

Her name began appearing in U.S. newspapers in the late 1800’s. For years, the London press made her story a “standing joke”, according to the New York Times. She was committed to the Claybury Lunatic Asylum in February of 1896 and died there in the fall of 1898. The Hutchinson News (Kansas, Sep 07 1893) had this to say about Jane Cakebread: “Jane takes the cake.”

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Ghost Town Wednesday: Burning Bush Colony (Texas)

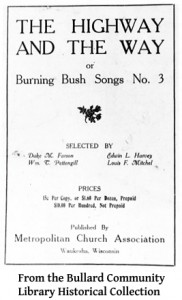

This “ghost town” in East Texas is known as the Burning Bush Colony. It was an “intentional community” founded as an offshoot of the Methodist Church. Headquartered in Waukesha, Wisconsin, this splinter group of “Free Methodists” called themselves the “Society of the Burning Bush”, or more formally the Metropolitan Church Association. The organization was funded by two wealthy benefactors, Duke M. Farson and Edwin L. Harvey.

This “ghost town” in East Texas is known as the Burning Bush Colony. It was an “intentional community” founded as an offshoot of the Methodist Church. Headquartered in Waukesha, Wisconsin, this splinter group of “Free Methodists” called themselves the “Society of the Burning Bush”, or more formally the Metropolitan Church Association. The organization was funded by two wealthy benefactors, Duke M. Farson and Edwin L. Harvey.

Farson was a bond broker in Chicago and Harvey a wealthy hotel owner. The group was founded in 1900, citing increased formality of the Methodist Church. Colonies were first established in Virginia, West Virginia and Louisiana. In 1912 the society made plans for a colony in Texas and chose an old plantation near Bullard that had been originally owned by Joseph Pickens Douglas.

The land was purchased in 1907 by Charles Palmer, cultivated and planted with pecan and plum trees. Farson made a deal with Palmer, exchanging the fifteen hundred and twenty acres near Bullard for various properties in Idaho, Illinois and New Mexico. Church administrators arrived in 1912 and set up their headquarters in the mansion.

The land was purchased in 1907 by Charles Palmer, cultivated and planted with pecan and plum trees. Farson made a deal with Palmer, exchanging the fifteen hundred and twenty acres near Bullard for various properties in Idaho, Illinois and New Mexico. Church administrators arrived in 1912 and set up their headquarters in the mansion.

Later that year three hundred and seventy-five church members arrived on a chartered train from the north. They were temporarily housed in the mansion while work began on family homes and dormitory-style buildings for single male and female members. Water and sewage systems were installed and a large wooden tabernacle and school were planned as well.

Church members were required to live communally, eating in a common dining hall and giving up all their worldly possessions upon joining the society. In July of 1905 the society’s publication, called the Burning Bush, advocated that instead of tithing ten percent, adherents were required to give everything to the church:

The reader probably well knows, we preach that we must sell all and follow Jesus. If God permits in this dispensation, for a man to remain on a farm or business, he must give all his earnings to the Lord. The old ‘ten per cent’ is now done away and ‘all’ is the amount to be given to Jesus. Hallelujah, the property once given to Jesus, all Hell is enraged. The Prophet said, he that departed from evil is accounted mad.

There was no type of class system, and though they welcomed visitors onto their property their contact with the “outside world” was limited by choice. Although they used the latest farming equipment available at the time, harvests were unimpressive, apparently due to their lack of knowledge in utilizing southern farming techniques.

Liquor and tobacco were strictly forbidden, yet the only reprisal if caught with the contraband was to take the transgressor to the tabernacle and pray and wail over them, according to the Texas State Historical Association. Their lives in the tight-knit community were centered on work and worship.

One resident of Bullard, L.B. Lynch, recalled years later his visits to their services as a ten-year old boy: “They rolled on the floor, they hollered a lot, and they stood on the benches when they got religion.” They had their own hymnal as depicted below from Ghost Towns of Texas by T. Lindsay Baker (part of the historical collection of the Bullard Community Library):

Five songbooks were published between 1902 and 1913 and many of the songs were written by church and community leaders. The books cost ten to twenty-five cents a copy, and were sold for several decades.

Five songbooks were published between 1902 and 1913 and many of the songs were written by church and community leaders. The books cost ten to twenty-five cents a copy, and were sold for several decades.

The worship services were intensely emotional. According to the Texas State Historical Association, “one local resident later remembered that the ‘Bushers would turn back flips in church and roll around on the sawdust floor.’ Much of the service was devoted to singing, during which the congregation jumped up and down. Because of this practice, the group was sometimes called the ‘Holy Jumpers.’”

Their original idea had been self-sufficiency, with all they needed contained within their own tight-knit community, but it never happened. With inadequate income derived from the sales of crops, Farson and the Metropolitan Church Association contributed large amounts of money to subsidize the Texas colony. However, it simply was not enough, especially after Farson’s bond business crashed in 1916.

Members began to seek work outside the commune, and as required, turned over one hundred percent of their wages to the church. Still struggling with insufficient funds and inadequate food supplies to remain self-sustaining, the colony began purchasing groceries on credit. The bills piled up and in 1919 the local merchant, J.L. Vanderver, sued for the twelve thousand dollars in outstanding notes.

The county sheriff seized the property and sold it all at a Tyler auction on April 15, 1919 – as it turned out, Vanderver purchased everything for one thousand dollars. Most of the colonists left Texas and returned to the North, although a small contingent remained. Eventually the old mansion and all the Burning Bush Colony buildings were bulldozed. The only remnant left today is a pecan orchard located across the street from Bullard High School.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

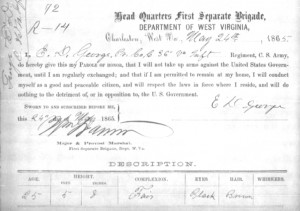

Tombstone Tuesday: Euphronius Daniel “Frone” George

Euphronius Daniel “Frone” George was born in April of 1840 in Lunenburg County, Virginia to parents James and Ermine (or Armine) George. Frone was their second son and the 1850 census enumerated six children for James and Ermine, ranging in age from ten to one.

Euphronius Daniel “Frone” George was born in April of 1840 in Lunenburg County, Virginia to parents James and Ermine (or Armine) George. Frone was their second son and the 1850 census enumerated six children for James and Ermine, ranging in age from ten to one.

In 1852, James died and it appears that his oldest son William and youngest daughter Mary may have also died sometime between the 1850 and 1860 censuses. In 1860 Ermine was a widow living “North of the Court House” in Raleigh County, Virginia (soon to be West Virginia) with her children Frone, Henry and Harriet, who was listed as a spinster at the age of seventeen.

Ermine moved to the county in 1857 with sons Frone, Henry and James who all served the Confederacy during the Civil War. According to Raleigh County history, Frone was “a noted fiddler in his younger days and was often the whole orchestra at the dances held in the neighborhood of the [Army] camp.”

Frone was an early enlistee, signing up on June 3, 1861. Henry, only seventeen, signed up the same day and records indicate he was later captured and served as a nurse at Camp Douglas, Illinois near Chicago. James enlisted in April of 1862, joining his brothers in Company C of the 36th Regiment of the Virginia Infantry.

Frone was wounded twice and Civil War records indicate that one incidence occurred on September 8, 1864. A Raleigh County history book included the following story about one of those incidences:

Frone was wounded twice and Civil War records indicate that one incidence occurred on September 8, 1864. A Raleigh County history book included the following story about one of those incidences:

Frone George, a soldier of the Confederacy for four years was wounded twice. Says he saw himself “shot ON the breast – looked at the minie ball as it hit him – did not penetrate, but made a very sore, black spot and hurt worse than if it had gone inside” says he could have stayed under cover but did not think the dam Yankee could shoot straight enough to hit him.

On May 24, 1865 at the headquarters of the First Separate Brigade in Charleston, West Virginia, Frone (E.D.) George signed his parole papers, promising to conduct himself “as a good and peaceable citizen” and never again take up arms against the United States Government.

Frone returned home and on January 21, 1868 he married Mary Keffer in Raleigh County. In 1870 he moved to Beckley and opened a blacksmith shop which he operated for over forty years. Mary’s father Samuel may have worked with Frone since they are enumerated as next door neighbors and both listed as blacksmiths in the 1870 census.

Their first son William was born in 1869, likely in honor of Frone’s older brother William. Their only daughter Leona was born in 1872, second son Frederick Clyde was born in 1874 and their last child Charles Edward was born in 1876. William was tragically killed by lightning on August 20, 1900 while working as a carpenter. The architect of the project, J. Price Beckley, grandson of the town’s founder General Alfred Beckley, was also killed.

Frone continued to work as a blacksmith, known by his friends and neighbors as a “man of many abilities . . . about whom volumes could have been written without great effort.” He died on October 17, 1918 and is buried in the Wildwood Cemetery in Beckley, alongside Mary who died in 1926.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Mothers of Invention: Thank a Woman

Melitta – does that name sound familiar? Today its namesake’s invention is a coffee machine necessity. If you enjoyed a steaming cup of home-brewed coffee this morning, sans coffee grounds, you have a woman to thank for that.

Amalie Auguste Melitta Liebscher, who later married Hugh Bentz, was born in Dresden, Germany in 1873. As a housewife, she began experimenting with ways to eliminate coffee grounds from her brewed coffee and also make it less bitter-tasting. A common practice at the time was to use a piece of cloth, or even items like socks to filter coffee, but neither method was particularly effective.

Amalie Auguste Melitta Liebscher, who later married Hugh Bentz, was born in Dresden, Germany in 1873. As a housewife, she began experimenting with ways to eliminate coffee grounds from her brewed coffee and also make it less bitter-tasting. A common practice at the time was to use a piece of cloth, or even items like socks to filter coffee, but neither method was particularly effective.

A story that circulates on the internet (true or not, I don’t know) is that Melitta was compelled to find a method to filter out coffee grounds because she had observed grounds stuck in her friends’ teeth while attending a coffee klatch. Whatever the impetus for the experimentation, she finally came up with the solution, a simple one actually. After experimenting with several methods, she tried a piece of blotting paper from her son’s school exercise book. It turned out to be a brilliant idea, for after all the purpose of this type of paper was to absorb liquids.

Her simple invention was patented on June 20, 1908 and by the end of that year she had a business, employing her husband and two sons to assist with production and management. In 1909 her new invention won an award at the Leipzig Trade Fair and two awards followed in 1910 at the International Health Exhibition and Saxon Innkeepers’ Association.

Her simple invention was patented on June 20, 1908 and by the end of that year she had a business, employing her husband and two sons to assist with production and management. In 1909 her new invention won an award at the Leipzig Trade Fair and two awards followed in 1910 at the International Health Exhibition and Saxon Innkeepers’ Association.

World War I brought stringent rationing of paper products, and coffee beans were hard to come by due to blockades designed to cutoff Germany from the rest of the world. With her husband conscripted to serve in the Romanian Army, Melitta supported herself by selling cartons.

Following the war, the company began to expand and by 1928 was employing eighty employees working double shifts. Her son Horst eventually took over the leadership of the company after Melitta transferred her majority stake to her sons Horst and Willi.

World War II brought another halt to commercial production when the company was ordered to assist in the war effort. Later, Allied troops used the facility for “provisional administration” for several years. In 1948 production resumed and by the time Melitta died in 1950 the company had made almost five million Deutsche Marks since its founding.

Melitta’s grandsons, Thomas and Stephen Bentz, now run the company, and today their product line includes premium coffees, basket filters and earth-friendly bamboo filters. A piece of blotting paper and a little female ingenuity was the beginning of an international multi-nillion dollar business.

March is Women’s History Month, so look for more articles about amazing women – “Mothers of Invention”, “Feisty Females” and more.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Feisty Females: Jessie Daniel Ames

Today’s article closes out the month of February, also known as Black History Month, with a story about an anti-lynching activist Southern white woman, Jessie Daniel Ames. She was also the founder of the Texas League of Women Voters in 1919 and served as its first president, believing that it was the role of various women’s organizations to help solve the country’s racial problems.

Today’s article closes out the month of February, also known as Black History Month, with a story about an anti-lynching activist Southern white woman, Jessie Daniel Ames. She was also the founder of the Texas League of Women Voters in 1919 and served as its first president, believing that it was the role of various women’s organizations to help solve the country’s racial problems.

Jessie Harriet Daniel was born on November 2, 1883 in Palestine, Texas to parents James and Laura Daniel. Her father was a railroad worker, and after the family moved to Georgetown in 1893 Jessie enrolled in the Ladies’ Annex at Southwestern University at the age of thirteen.

The Ladies’ Annex opened in 1889 and was a self-contained boarding and classroom facility, according to Southwestern University. Following the Civil War, the so-called separate-but-equal doctrine was applied not only to address racial equality but equal opportunities regardless of gender. Essentially, the university was required to provide separate living quarters for women who wanted to pursue an education.

The Ladies’ Annex opened in 1889 and was a self-contained boarding and classroom facility, according to Southwestern University. Following the Civil War, the so-called separate-but-equal doctrine was applied not only to address racial equality but equal opportunities regardless of gender. Essentially, the university was required to provide separate living quarters for women who wanted to pursue an education.

The facilities included living quarters, an art studio, a chapel, a gym and meeting rooms for three sororities and two literary societies. The proximity of these buildings to the main campus was planned so that the distance for either male or female students would be fairly equal, thus allowing all students to access the school’s main facilities easily.

Jessie graduated with a Bachelor of Arts degree in 1902 and then relocated to Laredo with her family. In June of 1905 she married Roger Post Ames, an Army surgeon and associate of Walter Reed. Together they had a son and two daughters, yet spent much of their married life living apart. Ames worked in Central America fighting yellow fever, while Jessie remained in the States. According to Dan Utley of Austin, the couple experienced difficulties in their marriage and his family never accepted Jessie (read Utley’s interesting narrative here).

In 1914, Roger Ames died of blackwater fever in Guatemala. Jessie had visited him in August and thought that perhaps their relationship had improved. She was pregnant with their third child when he died four months later. Jesse, then thirty-one years old, had already lost her father three years earlier. To provide for her family she moved in with her mother and helped run their family business, a telephone company in Georgetown.

Her involvement with several Methodist women’s organizations was the impetus for her activism in the women’s suffrage movement. In 1916 she organized local suffrage associations across Texas and worked to ensure that Texas was the first state to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment to the Constitution in 1919. With the founding of the Texas League of Women Voters, she served as the organization’s first president and was a delegate to the Democratic Convention in 1920, 1924 and 1928.

Her activism extended to racial issues in 1929 when she became a director for the Commission on Interracial Cooperation. Although the organization’s name implied that the group was “interracial” it was in fact founded in large part by a group of liberal white Southerners. The group strongly opposed lynching, mob violence and the so-called Black Codes which were put in place following the Civil War to restrict the freedoms of emancipated slaves.

The Commission was based in Atlanta and Jesse relocated there in 1930 to assume the position of national director of the CIC Woman’s Committee. That same year she founded the Association of Southern Women for the Prevention of Lynching. In the face of opposition and threats, forty thousand women across the South signed the Pledge Against Lynching:

We declare lynching is an indefensible crime, destructive of all principles of government, hateful and hostile to every ideal of religion and humanity, debasing and degrading to every person involved…[P]ublic opinion has accepted too easily the claim of lynchers and mobsters that they are acting solely in defense of womanhood. In light of the facts we dare no longer to permit this claim to pass unchallenged, nor allow those bent upon personal revenge and savagery to commit acts of violence and lawlessness in the name of women. We solemnly pledge ourselves to create a new public opinion in the South, which will not condone, for any reason whatever, acts of mobs or lynchers. We will teach our children at home, at school and at church a new interpretation of law and religion; we will assist all officials to uphold their oath of office; and finally, we will join with every minister, editor, school teacher and patriotic citizen in a program of education to eradicate lynchings and mobs forever from our land.

At that time in history, African American males were most often lynched for allegedly raping white women. More often that not, however, the allegations were false and innocent men lost their lives. Jesse strongly believed that white women need not fear, nor did they require special protection from, African American men. In her opinion, the motive for lynching was purely racial hatred.

She organized her members and trained them to go out in their own communities and talk with judges and law enforcement officials, urging them to sign the pledge as well. Interestingly, however, Jessie Ames opposed a federal anti-lynching law, believing perhaps that culture and society needed to change rather than a law requiring compliance. She also believed that an anti-lynching law would only result in more violence against blacks.

Indeed, Southern Senators had tried to filibuster the law and it went nowhere at the federal level. By 1937 the Association of Southern Women had eighty-one state, regional and national groups organized across the country. In 1942 the CIC was replaced by the Southern Regional Council, the Association dissolved, and Jessie retired to Tyron, North Carolina.

Despite threats of physical violence and intense Southern political opposition, the Association had seen progress. By 1940 there were no instances of African American lynchings, records of which had stretched back to the Civil War. In North Carolina, Jessie continued her activism by participating in Methodist Church activities, black voter registration drives and a women’s study group on world politics.

What fueled Jessie Daniel Ames’ resolve to fight as passionately for racial equality as she had women’s suffrage? Historian Jacqueline Dowd Hall called it a “psychological bridge” which she crossed to connect the two issues of social feminism and racial equality.

Perhaps it was due in part to the rise of the Ku Klux Klan; 1930 was also a year of heightened mob violence across the South. It’s easy to see that her activism in the areas of both women’s rights and racial equality eventually bore fruit. In the 1950’s the matter of school desegregation was brought to the judicial system, the Civil Rights Act was signed in 1964, followed by the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and later the proposed Equal Rights Amendment.

In 1968, Jessie Daniel Ames returned to Texas for health reasons and lived there until her death on February 21,1972 in an Austin nursing home.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

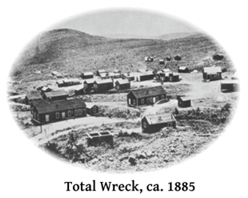

Ghost Town Wednesday: Total Wreck, Arizona

In 1879 silver was discovered in the eastern Empire Mountains of Arizona and the claims were held by John T. Dillon. According to Ed Vail, author of The Story of a Mine, one of the mines and the little town that sprung up nearby got their name from remarks made by Dillon when he signed the recording papers with Vail’s brother Walter in 1881.

In 1879 silver was discovered in the eastern Empire Mountains of Arizona and the claims were held by John T. Dillon. According to Ed Vail, author of The Story of a Mine, one of the mines and the little town that sprung up nearby got their name from remarks made by Dillon when he signed the recording papers with Vail’s brother Walter in 1881.

Walter asked him for a name and Dillon said, “Well, the mineral foundation is almost a total wreck,” alluding to the fact that it was located beneath a quartzite ledge that looked like a total wreck. The name stuck and on August 12, 1881 a post office was established.

The Los Angeles Times reported in 1882 that the appearance of the town, however, had nothing to do with its name: “The town of Total Wreck has no appearance of a wreck. It is a thrifty, neat-looking village, the streets laid out at right angles. The main street is named Dillon street in honor of the discoverer of the mine, and the first to discover minerals in this district.”

The Los Angeles Times reported in 1882 that the appearance of the town, however, had nothing to do with its name: “The town of Total Wreck has no appearance of a wreck. It is a thrifty, neat-looking village, the streets laid out at right angles. The main street is named Dillon street in honor of the discoverer of the mine, and the first to discover minerals in this district.”

By that time, the town had two stores, two hotels, a restaurant, five saloons, a carpenter, blacksmith, butcher, brewery, several Chinese laundries and over thirty houses with about two hundred residents. The town was fairly well organized with a deputy sheriff who could muster a posse of ninety men within an hour of any sign of trouble from rowdies or Indians.

On September 7, 1882, the Tombstone Weekly Epitaph reported that the townspeople were overjoyed to have received telegraph connections with the outside world. The Epitaph predicted that Total Wreck was “destined to be one of the most prominent mining camps in the Territory.”

In late November of 1882 one of the local businessmen, E.B. Salsig, was a victim of an attempted assassination by a man named John Drummond. According to the Tombstone Epitaph, Drummond had a reputation and was well-known to the residents of Tombstone. The two men were quarreling over Drummond’s interference with the sale of one of the mines in the district. Mr. Salsig apparently expressed an opinion that Drummond didn’t care for.

Drummond visited the store of Salsig &Sifford and called Salsig out on the street to have a few words, “applying to him epithets which most men resist.” Salsig was insulted and hit Drummond, only to have a revolver drawn on him and then shot three times by Drummond. The first shot resulted in only a flesh wound, while the second went through a wallet and bundle of letters, causing the lead ball to drop in Salsig’s pocket; “but for this it might have produced a fatal wound.”

The legend has oft been repeated that the love letters in his pocket saved Salsig’s life and he later married the woman who had penned the letters. Drummond, however, was arrested and bound over for trial, the Epitaph remarking “it would be well if such characters as this Drummond could be summarily dealt with.”

In June of 1883, several Mexicans were cutting wood in the Whetstone Mountains and were attacked by a band of Geronimo’s Apache warriors. Six Mexicans had been killed and were the first to be buried in the Total Wreck Cemetery. Today there is little, if any, evidence a cemetery ever existed, however.

In 1888 another resident, a miner named James Burns, was buried there after collapsing while working near one of the mine areas. Total Wreck was isolated and too far from Tucson for a coroner to reach the town before decomposition set in. Of necessity, in those times when such services weren’t available, a jury of Total Wreck citizens was sworn in by a Notary Public to investigate the cause of death. The jury determined that Burns died of natural causes due to a sudden rush of blood to his head, as evidenced by the dark appearance of his head, neck and face.

As predicted by the Epitaph in 1882, the Total Wreck claims were quite productive – by 1884 mines in the area had produced around a half-million dollars in silver bullion. On September 13, 1884, the Arizona Weekly Citizen was boasting that “the Total Wreck and many lesser known properties are just beginning to show the silver edge of their boundless wealth, and their prospective output means unprecedented prosperity to our country,” Despite those claims, however, the mill built in 1881 by the Empire Mining and Developing Company was closed at the end of 1884. In those days, booms were always followed by precipitous busts.

Attempts were made to revive operations in 1886, but in the late 1880’s and early 1890’s, mining interests declined. The Tombstone Prospector and Epitaph reported in early January of 1891 that the Total Wreck post office had been closed. The Silver Crash of 1893 resulted in the closing of hundreds of mines all over the West, and subsequently the withering away of hundreds of once-prosperous mining towns. Total Wreck slowly dwindled away as well, and today all that remains are a few walls and numerous holes in the ground.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

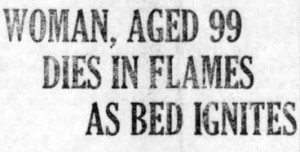

Tombstone Tuesday: Elizabeth Mosby Woodson Allison (1824-1924)

I can’t remember how I happened to stumble across the story of Elizabeth Mosby Woodson Allison – perhaps the tragic way she died caught my eye in a 1924 newspaper headline. By all accounts, she lived a full and long life, yet one of the most interesting aspects of Elizabeth’s life was her impressive family heritage.

I can’t remember how I happened to stumble across the story of Elizabeth Mosby Woodson Allison – perhaps the tragic way she died caught my eye in a 1924 newspaper headline. By all accounts, she lived a full and long life, yet one of the most interesting aspects of Elizabeth’s life was her impressive family heritage.

Elizabeth Mosby Woodson was born on December 30, 1824 in Franklin County, Virginia to parents Benjamin and Martha “Patsey” LeSueur Woodson. According to History of Monroe and Shelby Counties, Missouri, Benjamin “was a prominent teacher in the south-western part of Virginia.” Thus, his children received a good education. The family had connections to the well-known Virginia families of Woodson, LeSueur, Bacon and Randolph.

The LeSueurs were of French origin and traced their heritage back to Eustace LeSueur, a great French painter born in 1617 and referred to as the French Raphael. Other prominent LeSueur family members included Thomas LeSueur, a famous mathematician, and Peter LeSueur a wood engraver. The family’s immigrant ancestor in America, a French Huguenot named David LeSueur, came with Lafayette “to assist the colonies in their struggle for independence.”

The family’s most impressive heritage came through the Randolph family and connected Elizabeth, a first cousin twice removed, to the third President of the United States, Thomas Jefferson. Elizabeth’s grandmother Nancy Anna “Nannie” Woodson (who apparently married her cousin John Stephens Woodson) was the first cousin of Jefferson through his mother’s Randolph line.

The family’s most impressive heritage came through the Randolph family and connected Elizabeth, a first cousin twice removed, to the third President of the United States, Thomas Jefferson. Elizabeth’s grandmother Nancy Anna “Nannie” Woodson (who apparently married her cousin John Stephens Woodson) was the first cousin of Jefferson through his mother’s Randolph line.

That connection alone was impressive enough for the life-long member of the Daughters of the American Revolution, but through the Randolph line Elizabeth was also a direct descendant of Pocohantas through her son Thomas Rolfe. If there was a “royal lineage” in America, this might come close to qualifying as such.

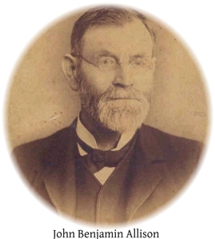

In 1840 Elizabeth and her family migrated to Monroe County, Missouri and were enumerated in Jackson for the 1840 census. In 1844 Benjamin purchased land to farm, but passed away in 1848 before Elizabeth married John Benjamin Allison on November 14, 1850. John was a farmer, and like his father-in-law Benjamin, a teacher.

To their marriage were born nine children: George Wilkerson, Benjamin Alexander, Dorothy Ann (“Dollie”), Arabella Jane, Martha Elizabeth, John Stephen, Emma Jemima (John and Emma were twins), William Mosby and Mary Edith – all living to adulthood with the exception of Martha who died in 1861.

To their marriage were born nine children: George Wilkerson, Benjamin Alexander, Dorothy Ann (“Dollie”), Arabella Jane, Martha Elizabeth, John Stephen, Emma Jemima (John and Emma were twins), William Mosby and Mary Edith – all living to adulthood with the exception of Martha who died in 1861.

In August of 1861, residents of Monroe County were alerted to the news that the “Federals were coming”. Governor Claiborne Fox Jackson had refused Abraham Lincoln’s request to send Missourians to fight for the Union, calling it an illegal action. In 1861 approximately one-fourth of the county’s population was slaves, so during the Civil War Monroe County was generally on the side of the Confederacy, although there were likely to have been Union sympathizers as well.

From the tone of Chronicles of the Civil War in Monroe County by B.C.M. Farthing, in general the county’s sympathies were more aligned with the South. Where the Allisons and Woodsons placed their loyalties is unclear, although one newspaper account in 1923 indicated that Elizabeth had “interesting experiences connecting her with the Civil War.”

According to accounts provided by family historians and in newspaper clippings, Elizabeth was a member of the Methodist Church who loved to sing hymns and recite poetry. After John passed away in 1904, she lived with her children at various times. In 1910 she was living with Mary and her family in Comanche County, Oklahoma; in 1920 Elizabeth was living with her daughter Arabella and her husband George Fischer in Dallas, Texas.

According to accounts provided by family historians and in newspaper clippings, Elizabeth was a member of the Methodist Church who loved to sing hymns and recite poetry. After John passed away in 1904, she lived with her children at various times. In 1910 she was living with Mary and her family in Comanche County, Oklahoma; in 1920 Elizabeth was living with her daughter Arabella and her husband George Fischer in Dallas, Texas.

On the occasion of her ninety-eighth birthday, a Dallas newspaper reported that Elizabeth was at that time the oldest living descendant of Pocohantas. She was in good health:

Despite the worries and cares which she has undergone during her many years, Mrs. Allison is still active and reads without the aid of glasses. She also recites poems and sings songs which she learned in her schooldays.

After all Elizabeth had lived through during her lifetime, her life ended tragically, apparently the result of her habit of smoking a corn-cob pipe. On the evening of February 19, 1924 she accidentally set herself on fire while smoking in bed, and by the time her son-in-law George Fischer reached her most of the clothing on her body had been burned away. George suffered severe burns trying to rescue her.

She was taken back to Missouri to be buried next to John in Audrain County. At the time of her death she was the oldest living descendant of Pocohantas, a fact included in accounts of her death in newspapers across the country.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!