Ghost Town Wednesday: Afognak, Alaska

The area around today’s ghost town was settled thousands of years ago. All along the Kodiak Archipelago the Alutiiq people lived, and like most other natives they hunted marine mammals (sea otters) and fished. The community was well organized – men and women both had work to do and goods were traded with other natives and settlements in the area.

The area around today’s ghost town was settled thousands of years ago. All along the Kodiak Archipelago the Alutiiq people lived, and like most other natives they hunted marine mammals (sea otters) and fished. The community was well organized – men and women both had work to do and goods were traded with other natives and settlements in the area.

In 1784, a Russian state-sponsored company arrived and began the conquest of Kodiak and the surrounding area by establishing an outpost at Three Saints Harbor. The area is said to have been well-populated at the time, perhaps around 8,000 residents, and after it was settled by the Russians became known as “Russian America”.

In 1784, a Russian state-sponsored company arrived and began the conquest of Kodiak and the surrounding area by establishing an outpost at Three Saints Harbor. The area is said to have been well-populated at the time, perhaps around 8,000 residents, and after it was settled by the Russians became known as “Russian America”.

This article is no longer available for free at this site. It was re-written and enhanced, complete with footnotes and sources and has been published in the August 2018 issue of Digging History Magazine. Other articles in this issue include, “Klondicitis! Dreamers and Drifters, Gunslingers and Grifters: Simply a Great Mad Rush”, “Mining Genealogical Gold: Bed and Board Notices (he said, she said)”, “Eleven Days of Hellish Heat”, and more. Should you prefer to purchase the article only, contact me for more information.

This article is no longer available for free at this site. It was re-written and enhanced, complete with footnotes and sources and has been published in the August 2018 issue of Digging History Magazine. Other articles in this issue include, “Klondicitis! Dreamers and Drifters, Gunslingers and Grifters: Simply a Great Mad Rush”, “Mining Genealogical Gold: Bed and Board Notices (he said, she said)”, “Eleven Days of Hellish Heat”, and more. Should you prefer to purchase the article only, contact me for more information.

I invite you to check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Tombstone Tuesday: Nellie Ross Cullens-Norwood (1859-1937) – Circle, Alaska

Since the weather has turned colder (and snowy in some places) I decided to cast out to the far north where snow has been on the ground for weeks – Circle, Alaska. A small marker was placed over Nellie Ross Cullens-Norwood’s grave in this remote area of Alaska. Only fifteen of the graves have any kind of marking on them according to Find-A-Grave, but perhaps as many as thirty-four people are buried in Circle Hot Springs Cemetery.

Since the weather has turned colder (and snowy in some places) I decided to cast out to the far north where snow has been on the ground for weeks – Circle, Alaska. A small marker was placed over Nellie Ross Cullens-Norwood’s grave in this remote area of Alaska. Only fifteen of the graves have any kind of marking on them according to Find-A-Grave, but perhaps as many as thirty-four people are buried in Circle Hot Springs Cemetery. I was intrigued by this one because I couldn’t locate any other Norwood’s buried in the area and Nellie was close to 80 years old when she died (noted on the marker). So, what is an elderly lady doing way up in remote Alaska living alone – there has to be a story here!

I was intrigued by this one because I couldn’t locate any other Norwood’s buried in the area and Nellie was close to 80 years old when she died (noted on the marker). So, what is an elderly lady doing way up in remote Alaska living alone – there has to be a story here!

This article was significantly enhanced with new research, complete with sources, and published in the August 2018 issue of Digging History Magazine. Should you prefer to purchase the article only, contact me for more information.

This article was significantly enhanced with new research, complete with sources, and published in the August 2018 issue of Digging History Magazine. Should you prefer to purchase the article only, contact me for more information.

I invite you to check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Civil War Before THE Civil War: Bloody Kansas (Part 2)

Soon after the Kansas-Nebraska Act was signed, the Massachusetts (New England) Emigrant Aid Society sent 200 “Free-Staters” (anti-slavery) to counteract the influences of southern states and neighboring Missouri who were strongly pro-slavery. The Massachusetts group was joined by similar organizations and responsible for the creation of the towns of Lawrence and Manhattan, Kansas. Lawrence would eventually become the center of the anti-slavery movement.

Soon after the Kansas-Nebraska Act was signed, the Massachusetts (New England) Emigrant Aid Society sent 200 “Free-Staters” (anti-slavery) to counteract the influences of southern states and neighboring Missouri who were strongly pro-slavery. The Massachusetts group was joined by similar organizations and responsible for the creation of the towns of Lawrence and Manhattan, Kansas. Lawrence would eventually become the center of the anti-slavery movement.

Missouri counties bordering Kansas were strongly in favor of slavery – so strong was the pro-slavery sentiment that Senator David Atchison sent 1,700 men from Missouri to Kansas to vote in the Kansas 1854 election. These were the so-called “Border Ruffians” who helped (illegally) elect a pro-slavery Kansas territorial delegate to Congress. Their votes were later ruled invalid, but that didn’t stop them from sending up 5,000 for the next election in 1855 which would elect the Kansas Territorial Legislature.

Missouri counties bordering Kansas were strongly in favor of slavery – so strong was the pro-slavery sentiment that Senator David Atchison sent 1,700 men from Missouri to Kansas to vote in the Kansas 1854 election. These were the so-called “Border Ruffians” who helped (illegally) elect a pro-slavery Kansas territorial delegate to Congress. Their votes were later ruled invalid, but that didn’t stop them from sending up 5,000 for the next election in 1855 which would elect the Kansas Territorial Legislature.

This article is no longer available for free at this site. It was re-written and enhanced, complete with footnotes and sources and has been published in the April 2018 issue of Digging History Magazine. Should you prefer to purchase the article only, contact me for more information.

This article is no longer available for free at this site. It was re-written and enhanced, complete with footnotes and sources and has been published in the April 2018 issue of Digging History Magazine. Should you prefer to purchase the article only, contact me for more information.

I invite you to check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Home Remedies and Quack Cures: Sobering Up – Dr. Haines’ Golden Specific

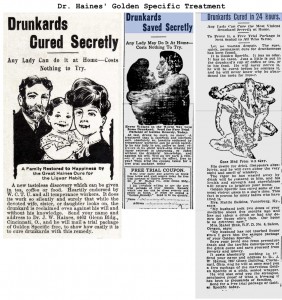

Before it became illegal to lie on the package label, this “cure” for alcoholism was called “Golden Specific” – later changed to “Golden Treatment” when the law went into effect. Dr. James Wilkins Haines of Cincinnati, Ohio claimed his medicine was endorsed by the Women’s Christian Temperance Union and that by merely slipping a bit of it into the husband’s cup of coffee in the morning, the wife could cure him of his taste for alcohol. According to Haines’ ads it was possible to cure one’s alcoholism in 24 hours! (Click to enlarge the image)

Before it became illegal to lie on the package label, this “cure” for alcoholism was called “Golden Specific” – later changed to “Golden Treatment” when the law went into effect. Dr. James Wilkins Haines of Cincinnati, Ohio claimed his medicine was endorsed by the Women’s Christian Temperance Union and that by merely slipping a bit of it into the husband’s cup of coffee in the morning, the wife could cure him of his taste for alcohol. According to Haines’ ads it was possible to cure one’s alcoholism in 24 hours! (Click to enlarge the image)

From the book Nostrums and Quackery, compiled by JAMA (Journal of the American Medical Association):

Any one with an elementary knowledge of the treatment of alcoholism knows how cruelly false such claims as these are. Not only is the statement that the stuff will cure the drunkard ‘without his knowledge’ and ‘against his will’ a falsehood, but it is also a cowardly falsehood in that it deceives those who in the very nature of the case will hesitate to raise any protest against the deception.

Notwithstanding the AMA’s point of view, Dr. Haines was probably seriously concerned with curing the alcoholic given the fact that he was a homeopathic physician, an educator, a spiritualist and a prominent Quaker minister. During his career he served as both President and Professor of Physics and Chemistry at Miami Valley College (Ohio), a Quaker institution.

In 1879 Haines was sued for malpractice and was also involved in a breach of marriage contract suit filed by Mary Bonner in 1878-1879. Haines eventually married another woman and paid Bonner $1,000 to settle the suit. The Society of Friends of Miami Ohio disowned him over his scandalous behavior; he later apologized and was eventually re-instated.

In 1879 Haines was sued for malpractice and was also involved in a breach of marriage contract suit filed by Mary Bonner in 1878-1879. Haines eventually married another woman and paid Bonner $1,000 to settle the suit. The Society of Friends of Miami Ohio disowned him over his scandalous behavior; he later apologized and was eventually re-instated.

“The following acknowledgment has been read and accepted: Dear Friends: Having for some time past, engaged in a multiplicity of business as to be beyond my ability to meet promptly, all my promises ~~ And having, through unwatchfulness, become entangled in matters that have hindered my growth in the ministry, and brought reproach upon the Truth, I feel to condemn the same, and trust that Friends will overlook them, and restore me to the unity and Christian Fellowship of the Society ~~ James W. Haines (Minutes of Miami Monthly Meeting of Women Friends held 23rd of 7th mo. 1879, page 179, located in the Quaker Archive, Wilmington College, Wilmington, Ohio). “ (Quaker Genealogy in Southwest Ohio).

James Haines was the only child of Seth Silver Haines. After James invented “Golden Specific”, his father built a sanitarium in 1861 on the family property where the afflicted could come and be treated with the cure. Haines claimed the drug was odorless and tasteless so that indeed the cure could be administered without the loved one’s knowledge. According to the JAMA report cited above, an analysis of Golden Specific found it comprised of the following ingredients:

Capsicum – found in peppers, and as we all know, causes a burning sensation

Ipecac – typically used to induce vomiting

Alkaloids – from the Arabic translates to “ashes of plants”

Lactose – milk sugar

Starch – probably used to bind all ingredients together

So, basically the treatment was milk sugar, starch, capsicum and a minute amount of ipecac – hardly a cure for alcoholism or anything else for that matter.

The first treatment was “free” but one could pay $3.00 for the full treatment and receive a box of forty powders. With the “free” version of the treatment, folks were instructed to administer it surreptitiously. However, when payment was made for the full treatment the instructions were different – now they implied that the cure wouldn’t work as well unless the patient was ready to be cured and of his own free will partook of the cure. Furthermore, the woman who purchased the full treatment was admonished that “after patient has been under treatment for two days, give sponge (or towel) baths of warm salt water every three days for at least two weeks”. Of course, the caveat always was “if one treatment does not succeed, get another quick.” (Nostrums and Quackery)

Dr. James Wilkins Haines died in 1893 at the age of 44 following a brief illness. The obituaries written about him were filled with glowing praise:

He will be sadly missed in every walk of life. His mind was clear to the last moment and during all his sickness he expressed perfect trust in his Savior, and was anxious to depart and be with Him. During the last moments he assured his sorrowing parents that, standing on the brink of eternity, all was bright and peaceful beyond. The way seems especially dark to the saddened hearts of his devoted parents, who see no happiness in the years to come without the presence of their loved one. Mr. and Mrs. Haines have the sympathy of the entire community, who mourn with them. His funeral occurred on Tuesday, the 18th, at 1 P.M., at the home of his parents. (Quaker Genealogy in Southwest Ohio)

Apparently the company went on without him, however – the ads displayed above were posted in newspapers in the early 1900s. I found it a bit curious though that one of the ads was posted in the Deseret News, a Mormon newspaper.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Feudin’ and Fightin’ Friday: El Paso Salt War

San Elizario in El Paso County, Texas was the location of this conflict over mineral rights. San Elizario was founded in 1789 south of the Rio Grande River. In 1831 a flood changed the course of the river and San Elizario became an “island” between the two channels of the river. In 1836 the Republic of Texas set its southern boundary at the Rio Grande, so for a time the nationality of San Elizario residents was in question. With the Treaty of Hidalgo, the border was officially set at the southern channel, so San Elizario, already a thriving town (the largest between San Antonio and Santa Fe) was now officially Texan.

San Elizario in El Paso County, Texas was the location of this conflict over mineral rights. San Elizario was founded in 1789 south of the Rio Grande River. In 1831 a flood changed the course of the river and San Elizario became an “island” between the two channels of the river. In 1836 the Republic of Texas set its southern boundary at the Rio Grande, so for a time the nationality of San Elizario residents was in question. With the Treaty of Hidalgo, the border was officially set at the southern channel, so San Elizario, already a thriving town (the largest between San Antonio and Santa Fe) was now officially Texan.

Reconstruction brought changes to that part of Texas with Republicans settling in the area after the Civil War. But, as we saw in last weeks article Democrats soon began to assert their political muscle to regain power. The Southern Democrats did not mix well with the Hispanics and their culture so rivalries arose.

Reconstruction brought changes to that part of Texas with Republicans settling in the area after the Civil War. But, as we saw in last weeks article Democrats soon began to assert their political muscle to regain power. The Southern Democrats did not mix well with the Hispanics and their culture so rivalries arose.

This article was entirely re-written and enhanced (8-page article), complete with footnotes and sources and has been published in the March 2018 issue of Digging History Magazine. This issue featured quite a few stories about Texas, including “Galveston: The Ellis Island of Texas”, “Isaac Cline’s Fish Story”, “Searching for That EUREKA Moment: Who Were You Roy Simpleman?”, and more. Should you prefer to purchase the article only, contact me for more information.

This article was entirely re-written and enhanced (8-page article), complete with footnotes and sources and has been published in the March 2018 issue of Digging History Magazine. This issue featured quite a few stories about Texas, including “Galveston: The Ellis Island of Texas”, “Isaac Cline’s Fish Story”, “Searching for That EUREKA Moment: Who Were You Roy Simpleman?”, and more. Should you prefer to purchase the article only, contact me for more information.

I invite you to check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Ghost Town Wednesday – Rodney, Mississippi

Once upon a time this ghost town came within three votes of becoming the capital of Mississippi. Native Americans found it a good place to cross the Mississippi River long before the area was settled by the French in 1763, who named it “Petit Gulf”. In 1781 the Spanish took control of West Florida until in 1791 they ceded the property to an influential Mississippi Territory landholder, Thomas Calvit.

Once upon a time this ghost town came within three votes of becoming the capital of Mississippi. Native Americans found it a good place to cross the Mississippi River long before the area was settled by the French in 1763, who named it “Petit Gulf”. In 1781 the Spanish took control of West Florida until in 1791 they ceded the property to an influential Mississippi Territory landholder, Thomas Calvit.

As settlements were established in the area, Petit Gulf became an increasingly important port on the River. In 1814 the town name was changed to “Rodney” in honor of Judge Thomas Rodney who had presided at the Aaron Burr hearing. Dr. Rushworth “Rush” Nutt (see yesterday’s Tombstone Tuesday article about his son, Haller Nutt) was one of the early settlers in the area who wielded great influence through his agricultural innovations.Mississippi was admitted to the Union in 1817 and Rodney came close to becoming the capital of the newly formed state. In 1828 the town of Rodney was officially incorporated and population was on the rise in the area. Rodney boasted twenty stores, a church, newspaper and the state’s first opera house, and in 1830 Oakland College was founded nearby.

As settlements were established in the area, Petit Gulf became an increasingly important port on the River. In 1814 the town name was changed to “Rodney” in honor of Judge Thomas Rodney who had presided at the Aaron Burr hearing. Dr. Rushworth “Rush” Nutt (see yesterday’s Tombstone Tuesday article about his son, Haller Nutt) was one of the early settlers in the area who wielded great influence through his agricultural innovations.Mississippi was admitted to the Union in 1817 and Rodney came close to becoming the capital of the newly formed state. In 1828 the town of Rodney was officially incorporated and population was on the rise in the area. Rodney boasted twenty stores, a church, newspaper and the state’s first opera house, and in 1830 Oakland College was founded nearby.

In 1834 the first town newspaper, The Southern Telegraph, a four-page weekly was printed on Tuesdays. The area had become so prosperous with cotton growing and commerce that General Zachary Taylor decided to purchase property south of Rodney, paying $60,000 for over nineteen hundred acres of land.

An epidemic of yellow fever struck in 1843, so severe that it felled local doctors and was reported in the Philadelphia Inquirer and National Gazette, as well as local newspapers (Mississippi Free Trader and Natchez Gazette on October 7, 1843):

“Rodney, Miss – This village, about 40 miles above Natchez, has been visited by the yellow fever. A number of deaths, and a still greater number of well marked cases have occurred – in consequence of which, we are informed by a Natchez physician and another Natchez gentleman who visited Rodney two days ago, the village is almost depopulated. Even the only Apothecary’s shop in the place is closed, as are all the stores. Of course, there will be no need of quarantining against a village having no business and no inhabitants.”

Four years later yellow fever struck again, but wasn’t as devastating as in 1843. By the 1850’s, Rodney was the busiest port on the Mississippi River between New Orleans and St. Louis. The population had increased to around a thousand residents and there were even more businesses, including two banks, a hotel with a ballroom, churches and schools. In the 1860’s Rodney grew to four thousand residents with ever increasing commerce.

Rodney saw some Civil War action in June of 1863 when about forty Union troops arrived in town to launch a surprise raid on Confederate troops in the area. When Vicksburg fell on July 4, the Confederacy was severed, and for the next two years Union troops patrolled the River, shutting down river traffic.

The USS Rattler gunboat was stationed at Rodney, but the crew was under strict orders of Navy Admiral David Porter to remain on the boat. The Rodney Presbyterian Church was pastored by a Northern sympathizer, Reverend Baker. The Reverend invited the ship’s captain, Walter Fentress, to attend a Sunday service – on September 13, 1863 the Captain, accompanied by a lieutenant and eighteen other soldiers accepted the invitation. Fentress and his men wore their dress uniforms and sat quietly with the congregation. Only one of the men was armed with a hidden revolver.

As the second hymn was beginning, Confederate Cavalry Lieutenant Allen walked up to the pulpit, apologizing for the interruption and announced the church was surrounded by Rebels and demanding the Union sailors surrender immediately. Second Assistant Engineer Smith drew out his hidden pistol and fired, hitting Allen’s hat. Congregants dove for cover and the Rebels outside began to fire through the windows. Seventeen Union troops, including the Captain and Lieutenant were captured.

As soon as those left behind on the Rattler heard of the commotion in town, they commenced to fire upon the town and church. Lieutenant Allen demanded that all shelling be stopped or else the Union troops in his custody would be hanged. The shelling stopped and afterwards the crew was derided for being the first ever ironclad gunboat to be captured by a small contingent of cavalrymen. The citizens of Rodney then formed their own military company and the Presbyterian pastor soon left town.

In 1864 Union troops were dispatched to destroy a rumored Confederate contingency in Rodney. Many houses and businesses in town were plundered. Even so, Rodney did not suffer as much as other areas of the South, but enough damage had been done to bring about the inevitable decline of the town. In 1869 the town was almost entirely consumed by fire, but even that devastating event wasn’t as decisive as the next “disaster” to hit the town.

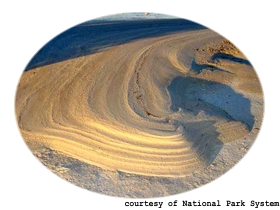

In 1870, the Mississippi River underwent a transformation – a large sand bar altered the course of the Mississippi, and the river was now two miles west of Rodney so the town was no longer a port. The railroad bypassed the town, and with the fire damage of 1869 and the loss of river commerce, many residents began to leave. In 1930 the Governor of Mississippi issued an executive proclamation ending the designation of Rodney as a town.

Few residents remain in the area today, but the town was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1980. Many original buildings are still standing, but are overgrown with vegetation, rotting and falling apart. The Presbyterian Church still stands and you can see the cannon ball hole in the front of the church.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Tombstone Tuesday: Dr. Haller Nutt – Natchez, Mississippi

I normally write Tombstone Tuesday articles about ordinary, everyday people who lived economically and physically challenging lives out on the American frontier somewhere. Today’s article is related to tomorrow’s Ghost Town Wednesday article, and since I ran across his name in my research for that article and found his history fascinating, I decided to write today’s article about Dr. Haller Nutt, a hugely successful businessman in southwest Mississippi and across the river in Louisiana.Haller Nutt was born to Dr. Rushworth “Rush” Nutt and Elizabeth (Kerr) Nutt on February 17, 1816 at the family’s Laurel Hill Plantation in Jefferson County, Mississippi. Haller’s father, Rush, had been educated at the University of Pennsylvania. In 1805, Rush decided to set out on horseback to check out the “Southwest” part of the country. Upon settling in Petit Gulf, Mississippi he set up a medical practice, married and bought a plantation.

I normally write Tombstone Tuesday articles about ordinary, everyday people who lived economically and physically challenging lives out on the American frontier somewhere. Today’s article is related to tomorrow’s Ghost Town Wednesday article, and since I ran across his name in my research for that article and found his history fascinating, I decided to write today’s article about Dr. Haller Nutt, a hugely successful businessman in southwest Mississippi and across the river in Louisiana.Haller Nutt was born to Dr. Rushworth “Rush” Nutt and Elizabeth (Kerr) Nutt on February 17, 1816 at the family’s Laurel Hill Plantation in Jefferson County, Mississippi. Haller’s father, Rush, had been educated at the University of Pennsylvania. In 1805, Rush decided to set out on horseback to check out the “Southwest” part of the country. Upon settling in Petit Gulf, Mississippi he set up a medical practice, married and bought a plantation.

Dr. Nutt began experimenting with developing a better strain of cotton that wouldn’t rot in the field. He traveled to Egypt to observe cotton growing methods and brought back Egyptian seed, crossing it with a Mexican variety. He also tinkered with Eli Whitney’s cotton gin invention by employing the use of steam to drive the machinery. Dr. Nutt, a medical doctor by training, seemed to have a knack for agriculture innovation – encouraging his neighbors to use contour plowing to decrease soil erosion, use field peas as fertilizer and to plow under cotton and corn stalks instead of burning them.

Dr. Nutt began experimenting with developing a better strain of cotton that wouldn’t rot in the field. He traveled to Egypt to observe cotton growing methods and brought back Egyptian seed, crossing it with a Mexican variety. He also tinkered with Eli Whitney’s cotton gin invention by employing the use of steam to drive the machinery. Dr. Nutt, a medical doctor by training, seemed to have a knack for agriculture innovation – encouraging his neighbors to use contour plowing to decrease soil erosion, use field peas as fertilizer and to plow under cotton and corn stalks instead of burning them.

His son, Haller, the subject of today’s article was quite successful himself and shared his father’s talent for agricultural innovation. At the University of Virginia, Haller studied math, chemistry and anatomy-surgery during his first term of 1833-34. During the second term of 1834-35 he studied natural philosophy, chemistry and anatomy-surgery.

When Haller returned home from the University in Virginia, he began to assist his father in plantation operations. In 1840 he married Julia Augusta Williams and they had eleven children. As an ambitious entrepreneur, Haller prospered and over his lifetime owned over twenty separate estates in Louisiana and Mississippi. Before the Civil War his net worth was said to be as much as three million dollars, owning thousands of acres of land and hundreds of slaves.

Some authors have credited the agricultural innovation of Rush Nutt to Haller, but I’ve found sufficient evidence that indicates that those described above are indeed Rush’s accomplishments. Nonetheless, his son was an innovator as well and became fabulously wealthy as a result. KnowLA (Encyclopedia of Louisiana) states that Haller was responsible for improvements in cotton bailing and cotton presses. Haller also compiled a collection of advice tidbits called Book of Receipts, Prescriptions, Useful Rules, etc. for Plantation and Other Purposes. He offered such advice as:

Cockroaches: Mix up fly stone (cobalt) with molasses and place it where they are found.

To kill lice on cattle, hogs, & horses – Wash them with the water in which Irish Potatoes have been boiled.

To measure the contents of a cistern: Square the diameter and multiply by decimals 7854, then by the altitude, then by 1728 & divide by 268-8/10 as in Article No. 4 – and your result is in gallons – or multiply half the diameter by half the circumference and then the altitude as before – or – multiply the whole diameter by the whole circumference, and divide by 1/4 others by altitude & 1728 & divide by 268-8/10.

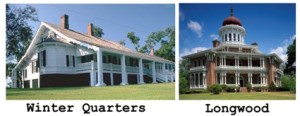

Two of Haller Nutt’s most notable properties were Winter Quarters and Longwood. The original Winter Quarters property had been purchased by his wife’s grandfather, Job Routh, in 1805. In 1850 Haller purchased the property and made several improvements. In the spring of 1860 construction began on Longwood, an opulent six-story, thirty thousand square feet mansion. He engaged the services of a Philadelphia architect and by the beginning of the Civil War the exterior had been largely completed. According to this web site, Haller’s slaves were tasked with the job of making over 750,000 bricks to be used in the construction of Longwood. But when the war broke out the northern builders and carpenters abandoned the construction site and headed back home. By 1862, nine rooms had been completed by using slave labor.

Rush’s and Haller’s various innovations through the years had helped boost the cotton industry in the deep South, which quite likely encouraged the use of increasingly more slave labor. Here, however, is where I found a curious fact about Haller Nutt. He was a Union sympathizer… in the deep, deep South, himself owning hundreds of slaves.

Rush’s and Haller’s various innovations through the years had helped boost the cotton industry in the deep South, which quite likely encouraged the use of increasingly more slave labor. Here, however, is where I found a curious fact about Haller Nutt. He was a Union sympathizer… in the deep, deep South, himself owning hundreds of slaves.

In this personal handwritten letter, he encourages Alonzo Snyder to run for election as a delegate to the secession convention:

Haller believed that secession would occur but hoped that it would be forestalled as long as possible, praying for reunion with the rest of the country except the New England states.

Even with construction halted on his Longwood estate, Haller was determined to press on despite the war and volatile political climate, but eventually he was forced to abandon the project until hostilities ceased. When Sherman began his march through the South, Haller and his family relocated to Natchez, Mississippi, leaving Winter Quarters in the hands of a caretaker. General Grant had ordered the destruction of everything not needed by the Union troops. Before Sherman’s March there were fifteen plantations lining the banks of St. Joseph Lake and when the smoke cleared, Winter Quarters was the only one still standing. The caretaker had been able to secure letters of protection from two of Sherman’s advance officers, General McPherson and General Smith.

Winter Quarters’ salvation notwithstanding, Haller Nutt suffered devastating financial losses during the War which led to foreclosure proceedings on his Louisiana plantations. On June 15, 1864, at the age of 48, Haller Nutt died of pneumonia. Some have suggested he died of a broken heart. His family was later successful in petitioning the federal government to compensate them for at least some of the damages incurred.

Winter Quarters was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1978. Longwood is owned and operated by Pilgrimage Garden Club as an historic museum.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Civil War Before THE Civil War – Manifest Destiny and Compromise (Part I)

President James K. Polk was on a mission to expand the country westward. The term “divine destiny” had been used by journalist John O’Sullivan in 1839, later evolving into what came to be known as “Manifest Destiny”. Part of Polk’s plans for westward expansion involved taking possession of a vast amount of land under Mexican control and it would require a two-prong attack.

President James K. Polk was on a mission to expand the country westward. The term “divine destiny” had been used by journalist John O’Sullivan in 1839, later evolving into what came to be known as “Manifest Destiny”. Part of Polk’s plans for westward expansion involved taking possession of a vast amount of land under Mexican control and it would require a two-prong attack.

Mexican-American War

John Fremont, accompanied by Kit Carson, was sent to the far west to stake a claim to California and Stephen Kearny was dispatched to New Mexico. In New Mexico, the governor fled Santa Fe (with lots of gold and silver) and Kearny’s troops easily secured Santa Fe without a single death. From there, Kearny continued westward to California to join up with Fremont.

This article is no longer available for free at this site. It was re-written and enhanced, complete with footnotes and sources and has been published in the April 2018 issue of Digging History Magazine. Should you prefer to purchase the article only, contact me for more information.

This article is no longer available for free at this site. It was re-written and enhanced, complete with footnotes and sources and has been published in the April 2018 issue of Digging History Magazine. Should you prefer to purchase the article only, contact me for more information.

I invite you to check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

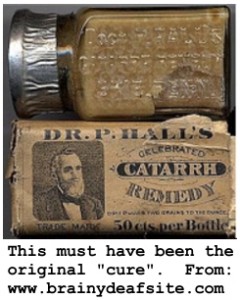

Home Remedies and Quack Cures: Hall’s Catarrh Cure

I’ve recently been performing a lot of historical and ancestral research by combing through digitized newspapers. Inevitably, in the newspapers of the mid-1800’s until the early 1930’s, I am reading advertisements extolling the benefits of so-called miracle cures, also known as patent medicines. These “medicines” claimed to cure everything from A to Z. So, I thought it would be fun and interesting to do a series on the history of patent medicine, or “nostrums” as they were called, and some of the quack cures that literally flooded the market in that era. Here and there I’ll do some articles on home remedies as well.

I’ve recently been performing a lot of historical and ancestral research by combing through digitized newspapers. Inevitably, in the newspapers of the mid-1800’s until the early 1930’s, I am reading advertisements extolling the benefits of so-called miracle cures, also known as patent medicines. These “medicines” claimed to cure everything from A to Z. So, I thought it would be fun and interesting to do a series on the history of patent medicine, or “nostrums” as they were called, and some of the quack cures that literally flooded the market in that era. Here and there I’ll do some articles on home remedies as well.

Today’s subject, “Hall’s Catarrh Cure,” caught my eye in an ad above a story I was researching this week, so I decided to do a little extra research on the history of this patent medicine – was it really a miracle cure?

Today’s subject, “Hall’s Catarrh Cure,” caught my eye in an ad above a story I was researching this week, so I decided to do a little extra research on the history of this patent medicine – was it really a miracle cure?

Background

First of all, what the heck is “catarrh”? According to Merriam-Webster’s Dictionary, “catarrh” is an “inflammation of the mucus membrane, chronically affecting the human nose and air passages.” Hey, I’ve had catarrh for years and didn’t know it!

In or around 1870, Frank J. Cheney purchased the rights to Dr. Henry S. Hall’s “cure” – a drug that Dr. Hall had formulated and prescribed to his patients. I was unable to locate any specific information on Dr. Hall himself but Cheney appears to be one shrewd and powerful (as in “connected”) businessman. Cheney Medicine Company did a booming business for several years …. until the patent medicine industry began to be investigated and exposed by scientists and the American Medical Association.

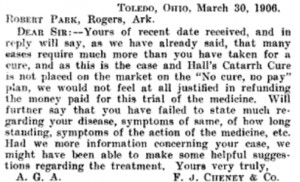

In 1871 Cheney began employing a very effective advertising campaign. His ads weren’t flashy but they were everywhere – by the late 19th century he was advertising in over sixteen thousand newspapers world-wide. This type of advertising was likely what kept newspapers of that day afloat. Cheney, at one point, estimated that the proprietary medicine industry paid out more than $20 million dollars to newspapers per year! (Click to enlarge images)

In 1871 Cheney began employing a very effective advertising campaign. His ads weren’t flashy but they were everywhere – by the late 19th century he was advertising in over sixteen thousand newspapers world-wide. This type of advertising was likely what kept newspapers of that day afloat. Cheney, at one point, estimated that the proprietary medicine industry paid out more than $20 million dollars to newspapers per year! (Click to enlarge images)

halls cattarh adsCheney employed hundreds of people and he had representatives throughout the country doing door-to-door sales. By the mid-1890’s the company was sending out 200,000 circulars daily at a cost of around $300 in postage per day.

Frank Cheney was a shrewd businessman. One of his “gimmicks”, shall we say, was to put a wrapper on every bottle of Hall’s Catarrh Cure which contained the following “guarantee”:

One hundred dollar reward for any case of catarrh that can’t be cured with Hall’s Catarrh Cure.

Do you think anyone ever received this so-called “one hundred dollar reward”? According to the Journal of the American Medical Association, Volume 46, Issues 14-26, one patient, Mr. Robert Parks, wrote to the Cheney Medicine Company requesting his reward. You see he had used 26 bottles of Hall’s Catarrh Cure without benefit – in fact, his condition had worsened. Mr. Parks received the following reply:

So apparently there was plenty of “wiggle room” in making these claims of cures. However, by the late 1890s and early 1900s, the patent medicine industry began to come under more scrutiny.

Proprietary Proprietors Strike Back

In response to the scrutiny and action threatened by state legislatures, Frank Cheney was instrumental in the formation of The Proprietary Association of America, its primary purpose being to protect the interests of the patent or proprietary medicine industry against state legislation and regulation.

For a period of time, Cheney served as the president of the Association and was largely responsible for the so-called “Red Clause” which was inserted in all advertising contracts with newspapers (printed in red ink). The Red Clause stated:

It is mutually agreed that this contract is void if any law is enacted by your State restricting or prohibiting the manufacture or sale of proprietary medicines.

Frank Cheney shared his advertising secrets and ploys with fellow members of the Association and for awhile those conversations and strategy sessions were kept from the public. An investigative journalist, Samuel Hopkins Adams, wrote a series of articles for Collier’s Weekly in 1905 exposing many of the false claims of these so-called miracle cures. Adams also exposed the Association’s secrets. As a result the general public was made aware of the fraud being perpetrated upon them, and the federal government began to take action.

The Pure Food and Drugs Act was enacted in 1906 and eventually the Food and Drug Act would be passed years later. Frank Cheney died in 1919 and his 1886 affidavit ad (see above) was still running in newspapers.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Feudin’ and Fightin’ Friday: The Jaybird-Woodpecker War

This little war fought in Fort Bend County, Texas had nothing to do with birds, but could very well be described as a race war.

Background

In the early 1820s, the area which comprised Fort Bend County was settled as a so-called “plantation district”. By 1861 when it was time to decide whether to secede from the Union this Texas county was one of the largest slave-holding counties in Texas. Not surprisingly, the slave holders voted 100 percent in favor of secession.

This article is no longer available for free at this site. It was published in the January-February 2019 issue of Digging History Magazine. Other articles featured in this issue include: “The Great Molasses Flood of 1919”, “Hell for Rent: A Nation Goes Dry”, “Edith, Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner?”, “Manumission: Free at Last (or perhaps not)”, “Free to Enslave”, and more. Should you prefer to purchase the article only, contact me for more information.

This article is no longer available for free at this site. It was published in the January-February 2019 issue of Digging History Magazine. Other articles featured in this issue include: “The Great Molasses Flood of 1919”, “Hell for Rent: A Nation Goes Dry”, “Edith, Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner?”, “Manumission: Free at Last (or perhaps not)”, “Free to Enslave”, and more. Should you prefer to purchase the article only, contact me for more information.

I invite you to check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!