Tweren’t really nothing much this little “war” — just a misunderstanding (maybe a little blown out of proportion), which was eventually settled by the U.S. Supreme Court, over the interpretation of the Louisiana Purchase and various treaties in ensuing years.

Tweren’t really nothing much this little “war” — just a misunderstanding (maybe a little blown out of proportion), which was eventually settled by the U.S. Supreme Court, over the interpretation of the Louisiana Purchase and various treaties in ensuing years.

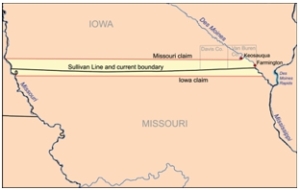

The disputed land was an approximately 10 mile-wide strip — was that land part of northern Missouri or southern Iowa? In 1820, Missouri entered the Union with the northern boundary being the so-called “Sullivan Line” or “Indian Boundary Line”. In 1816, surveyor John Sullivan conducted a survey in order to delineate the space between Osage Indian Territory and what was then just called Missouri Territory (new treaties had been drawn up with the Indians after the War of 1812). Sullivan erected markers along the way, but by the late 1830s those markers had more or less disappeared, making it unclear where the boundary lines laid.

The disputed land was an approximately 10 mile-wide strip — was that land part of northern Missouri or southern Iowa? In 1820, Missouri entered the Union with the northern boundary being the so-called “Sullivan Line” or “Indian Boundary Line”. In 1816, surveyor John Sullivan conducted a survey in order to delineate the space between Osage Indian Territory and what was then just called Missouri Territory (new treaties had been drawn up with the Indians after the War of 1812). Sullivan erected markers along the way, but by the late 1830s those markers had more or less disappeared, making it unclear where the boundary lines laid.

I ran across one person’s theory relating to Sullivan’s line that I found interesting. I’m not sure who the author is, however. This person had gleaned from other web sites the theory of “magnetic declination” or the difference between what the compass indicates is north (magnetic north pole) and what is really north (geographic north pole). He/she postulated the following:

From where he started in western Missouri, the (21st-century) declination is approximately 4 1/2 degrees; at the Des Moines, the declination is 2 degrees. Thus, as Sullivan worked east, the “straight” line angled to a decidedly east-north-easterly direction, especially in the eastern third, and he reached the Mississippi in what is now downtown Fort Madison, approximately three miles north of where he should have been. Whoops. The problem was compounded when the southern boundary of the Wisconsin Territory was stated to be the northern border of Missouri, locking the two in an endless loop.

There was mention of “Des Moines Rapids” in the survey as being some point of delineation. Then in the late 1830s when Iowa was ready to join the Union, “Des Moines Rapids” became a point of contention. Apparently, these rapids were actually located in the Mississippi River, just above where the confluence of the Des Moines River and the Mississippi is located (I guess they took the phrase literally that the rapids were in the Des Moines River).

Another survey, conducted by J.C. Brown, was commissioned by the state of Missouri. Since the Sullivan markers are now missing or difficult to locate, and he doesn’t seem to know that the rapids are located in the Mississippi, he sets out to find the rapids in the Des Moines River. He assumes he finds them (wrong assumption) in an area now known as Keosauqua. His survey results in adding a wider strip of land across the northern border than Sullivan’s original survey.

Missouri is satisfied with the results (of course) and wants to levy taxes in that newly acquired territory. However, most people in that soon-to-be-disputed strip of land considered themselves Iowans and didn’t take kindly to being taxed by Missouri.

One anecdote told is that Samuel Riggs and Jonathan Riggs were cousins and both sheriffs of their respective counties. Samuel was sheriff of Davis County, Iowa and Jonathan was sheriff of Schuyler County, Missouri. Jonathan arrested Samuel for breaking the laws of the state of Missouri and, in turn, Samuel arrested Jonathan for holding the office of sheriff in Missouri while living in Iowa. Samuel kept Jonathan in jail for two months.

With the arrest of Jonathan Riggs and the cutting down of three honey bee trees by a Missourian as payment for taxes, hundreds of Iowans and Missourians rushed to the disputed area to defend their claims in December 1839. Since Iowa was such a young state, they didn’t have much of a militia. One story relates that the Iowa militia was armed mostly with antique shotguns, flintlocks and ancestral swords — not exactly a fierce-looking military force. According to one author (Tales from Missouri and the Heartland, by Ross Malone), the Missourians were armed with a variety of weapons, including a sausage stuffer that one man planned to use (?!?). I can just imagine that there was plenty of whiskey brought along too!

The governors of both states then engaged in a war of words. After a month-long standoff, a committee of men from both militias met and and asked the two governors to submit the matter to Congress to resolve. Eventually the case known as State of Missouri v. State of Iowa was referred to the U.S. Supreme Court to decide. Ultimately, the “war” was won by Iowa, deciding that the original “Sullivan Line” was indeed the correct boundary.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

I thought it a bit amusing that the surveyors were a little “haphazard” we might say — the one author quoted in the article wondered whether Sullivan wasn’t aware of magnetic declination.