Elizabeth “Bessie” Coleman was born on January 26, 1892 to parents George and Susan Coleman, she being the tenth of their thirteen children. George Coleman was part African American and part Cherokee, a sharecropper in Atlanta, Texas which had been settled by former Georgia residents. While there were opportunities to make money in the local industries (railroads, oil, lumber), the Coleman family struggled. George moved his family to Waxahachie in 1894, hoping to do better for himself and his family.

Elizabeth “Bessie” Coleman was born on January 26, 1892 to parents George and Susan Coleman, she being the tenth of their thirteen children. George Coleman was part African American and part Cherokee, a sharecropper in Atlanta, Texas which had been settled by former Georgia residents. While there were opportunities to make money in the local industries (railroads, oil, lumber), the Coleman family struggled. George moved his family to Waxahachie in 1894, hoping to do better for himself and his family.

George purchased a quarter-acre plot of land and built a small three-room house in the black section of Waxahachie. By all accounts, Bessie’s early childhood was a happy one. She began school at the age of six and walked four miles each day to the all-black school where she excelled, especially in math.

In 1901, George Coleman left his family and headed to Indian Territory (Oklahoma) to pursue better opportunities, citing racial barriers too difficult to overcome in Texas. Susan, however, refused to accompany him and was left with four girls under the age of nine after her older sons also left home. Susan obtained employment as a cook and housekeeper. The family she worked for allowed her to live in her own home and also provided clothing for the girls.

In 1901, George Coleman left his family and headed to Indian Territory (Oklahoma) to pursue better opportunities, citing racial barriers too difficult to overcome in Texas. Susan, however, refused to accompany him and was left with four girls under the age of nine after her older sons also left home. Susan obtained employment as a cook and housekeeper. The family she worked for allowed her to live in her own home and also provided clothing for the girls.

Their routine, however, was disrupted every year when the Coleman family participated in the cotton harvest. Bessie continued to excel in school and when she had completed the eighth grade (probably all the primary education available to her at the time), she saved her money and entered the Colored Agricultural and Normal University in Langston, Oklahoma in 1910. Her money was exhausted after one term and she returned to Waxahachie where she worked as a laundress. By 1915 Bessie Coleman wanted more out of life so she headed to Chicago where her brother Walter lived.

She found work as a manicurist in the White Sox Barbershop and Susan and her remaining children joined her in 1918. Her brothers came home after World War I with war stories, including those of French female pilots. In 1919 the worst race riot in history took place in Chicago and Bessie would soon conclude she wanted something more out of life. Her ambition was to become a pilot like the French women her brothers boasted about.

At the age of twenty-seven she began pursuing a career in aviation, but first she had to find someone willing to train her. However, for a black woman those opportunities just didn’t exist in America at that time. Still determined to pursue her dream of becoming a pilot she obtained funding and a passport and headed to France in November of 1920.

The course, taught at Ecole d’Aviation des Freres Caudon, was normally ten months in length – Bessie completed it in seven. On June 15, 1921 Bessie Coleman received her pilot’s license from the Federation Aeronautique Internationale. She was the first black person, male or female, ever to do so and the only woman of the sixty-two candidates that year eligible for licensing.

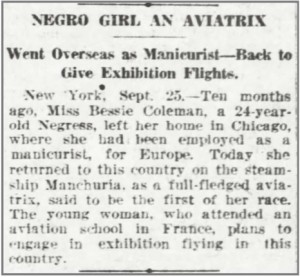

Upon her return to America in September she received widespread press coverage:

At that time in history flight exhibitions were a popular form of entertainment in the United States. Lacking skills to perform as a stunt pilot at those shows, Bessie returned to France for more training. She returned to the States in August of 1922, and on September 3 she was billed as “the world’s greatest woman flier” at an event held at Curtiss Field in New York City. Six weeks later she returned to Chicago to enthrall a crowd at the Checkerboard Airdome (now Midway Airport).

She continued to work as a stunt flier, but still had ambition to do more. Briefly she considered a movie career and traveled to California to earn money to purchase a plane of her own. She crashed the plane on February 22, 1923 and returned to Chicago to pursue her ultimate goal of opening her own flight school. It would take awhile to accomplish since along the way she had to overcome the barriers of both race and gender.

Back in Texas she began appearing in towns big and small across the state to give lectures and perform exhibitions. One stipulation she always insisted upon for her exhibitions – everyone, regardless of race, was to be admitted without being segregated. She was able to make a down payment on another plane and then continued lecturing in Georgia and Florida. Still planning to open a flight school, she also opened a beauty shop in Orlando to earn more money to put towards the flight school. Because she was still making payments on her plane, she borrowed planes and continued to perform exhibitions, even occasionally parachuting.

By spring of 1926 she had finally made the final payment on her plane and arranged to have it flown to Jacksonville, Florida where she would be performing on May 1. On April 30, Bessie and her mechanic took the plane up for a test flight. The mechanic was piloting and suddenly lost control of the plane. Bessie, who was not wearing her seat belt, was thrown from the open cockpit, plummeting two thousand feet to her death. The plane crashed and burned, killing the mechanic as well. It was later discovered that a wrench had accidentally slid into the gearbox, jamming it.

Bessie Coleman died on April 30, 1926 at the age of thirty-four. Her body was returned to Chicago for burial and several thousand mourners paid their respects. She would later have buildings and streets named in her honor. In 1995 the United States Postal Service honored her with a commemorative stamp. The accompanying resolution stated, “Bessie Coleman continues to inspire untold thousands even millions of young persons with her sense of adventure, her positive attitude, and her determination to succeed.”

Earlier this year I wrote an article about “Feisty Female” Cornelia Clark Fort, another pioneering aviator. If you haven’t yet read that article, check it out here. Also, Fannie Flagg’s latest book is a great read and loosely based on Cornelia’s story.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Trackbacks/Pingbacks