Sarah Connelly, I Feel Your Pain (Adventures in Research: War of 1812 Pension Records)

Here’s a look back at a 2019 article published in Digging History Magazine, a personal one, from an issue which featured the War of 1812:

I hadn’t looked at this particular line for some time, but after someone saw this particular surname on my family’s pedigree chart (with an interesting story of someone with the same surname) I decided to take another look. I suspect I set it aside some time ago because, at least circumstantially, it appeared I had the correct parents for my third great grandmother Mary Ann Connelly, yet I couldn’t locate absolute proof.

So, a little more digging was in order. Curiously, I had several hints for Mary Ann’s mother but not her father, Henry Connelly. After realizing I had mistakenly input an incorrect birth location — dang auto-correct(!) — I registered several hints for him. After clicking on the new hints I found previously posted bits and pieces of War of 1812 Pension and Bounty Land Warrant application files. These were actually part of an extensive package (41 pages) of what turned out to be a “Eureka!” moment for researching this family line.

Henry and Sarah (Phillips) Connelly married on August 20, 1810 in Clay County, Kentucky, this according to affidavit after affidavit from Sarah Connelly following passage of the War of 1812 Act of February 14, 1871. In part:

The act of February 14, 1871, granted pensions to survivors of the war of 1812, who served not less than sixty days, and to their widows who were married prior to the treaty of peace.1

Sarah began her quest not long after the bill’s passage, engaging the services of attorney William F. Terhume in April.

Henry, born circa 1787, enlisted in the Kentucky militia on November 10, 1814 and was honorably discharged on May 10, 1815. Among the qualifications for a widow’s pension was to prove you and your now-deceased spouse had married and co-habitated prior to the Battle of New Orleans (January 8, 1815).

In 1871 Sarah was eighty years old, and while she would eventually have problems remembering the company Henry had served with and a few other details, she remembered the date of her marriage and the ceremony performed by Reverend Spencer Adams, a Baptist preacher. Clay County was established in December 1806, carved from parts of Madison, Floyd and Knox counties. Whether her marriage in the early days of Clay County contributed to her inability to locate proof is unclear, as Sarah discovered there was no official or public record of the marriage. The marriage had been witnessed by four long-deceased individuals, and Henry had passed away in 1859 (dropsy according to the 1860 Mortality Schedule).

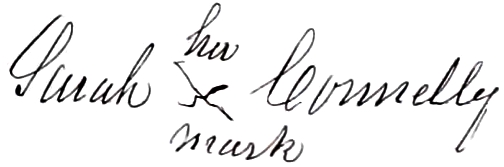

Mr. Terhume began the process after an agreement for payment of services to be rendered ($25.00) was executed on April 5, 1871. By her mark Sarah agreed to those conditions:

Terhume wrote the first letter six days later, addressed to the Commissioner of Pensions:

Terhume wrote the first letter six days later, addressed to the Commissioner of Pensions:

I enclose a pension claim under the late act of Congress for a widow of a soldier who served in the war of 1812.

I trust you will find it in sufficient form. Permit me to suggest that these claims should receive early attention for the reason that the applicants are quite aged and may not live many of them to enjoy the bounty of the government.2

Terhume also inquired about instructions, and if any existed, requested copies. Ever so promptly (not!) the government sent a circular dated September 16, 1871. In the following order the government required proof:

● A certified copy of a church or other public record.

● An affidavit of the officiating clergyman or magistrate.

● The testimony of two or more eyewitnesses of the ceremony.

● The testimony of two or more witnesses who know the parties to have lived together as husband and wife from the date of their alleged marriage, the witnesses stating the period during which they knew them thus to cohabit.

● Before any of the lower classes of evidence can be accepted, it must be shown by competent testimony that none higher can be obtained.3

As previously noted the first three forms of proof were out of the question — three strikes, Sarah is out?

Included in the first correspondence, executed on the same day as the fee agreement, was an extensive affidavit witnessed and averred to by Sarah’s son-in-law William H. Pugh (my third great grandfather) and his brother George Washington Pugh who had married a woman also surnamed Connelly (she also being a Mary, and Mary Ann’s cousin I believe).

In this affidavit significant information was provided as evidence Henry Connelly had served during the War of 1812. Included with information provided was a proclamation of total allegiance to the United States. Given that the Civil War was still a touchy subject, perhaps Mr. Terhume thought it best to include this statement:

… and further that at no time during the late Rebellion against the authority of the United States did I [Sarah] adhere to the enemies of the United States government neither gave them aid or comfort, and I solemnly swear to support the Constitution of the United States.4

It was also noted that Sarah had already received a land warrant from the government. (Eventually the government would indeed produce its own evidence, a Widow’s Claim for Bounty Land originally authorized on August 31, 1864.)

Her son-in-law and his brother signed similar statements, both pledging fealty to the federal government. Based on the government’s September 1871 response the original statements had been insufficient to move forward with Sarah’s claim. The matter was “suspended” in January 1872 until proof of cohabitation could be provided.

Meanwhile, Terhume had been pursuing, with diligence, means of proof, yet without success. He continued to try and locate someone in Kentucky who would remember, but by September 25, 1872 had received no response. Terhume had found someone willing to keep digging in Kentucky but would likely have no further proof until at least January of 1873.

Sarah was in a bind as far as the matter of marriage proof was concerned. So, what to do when you’re in a pinch? Call on your in-laws, of course!

It’s a bit curious to me the family didn’t think of this before, but on January 13, 1873 an affidavit was signed by two of Sarah’s in-laws. One was Mary Pugh, George’s wife and the other was Frances Pugh, my other fourth great-grandmother. I like to call her “Feisty Frances”.

Frances Townsend Pugh was born in Virginia on June 26, 1794. A few months before her sixteenth birthday she married William Pugh. Their marriage produced twenty-one children, thirteen of whom lived to adulthood. William (born in 1787) died in 1869 and Frances, according to Vernon County, Wisconsin history, was “well preserved and enjoyed good health.”5

At the age of ninety she was still able to take walks and one day came upon a rattlesnake with seven rattles. The snake slithered away but Frances grabbed a stick, “hunted the venomous reptile out from his hiding place and killed it; this took more courage than most of her children and grandchildren would have possessed.”6

Frances was certain Henry and Sarah had been married prior to the Battle of New Orleans because she recalled the birth of one of her own children the same year and day of the month as a child Sarah had delivered. While Mary Pugh (George’s wife) agreed about the marriage, Frances’ statement was the strongest.

Their statements helped settle the matter it appears, because on January 23, 1873 the government issued a “Brief of Claim for a Widow’s Pension” for Sarah Connelly. The brief referenced a report from the Bounty Land Division, along with previous statements by George and William Pugh and Frances and Mary Pugh.

Sarah Phillips Connelly was granted a widow’s pension of eight dollars per month. Sarah died on September 6, 1874 at the age of eighty-three. I found Sarah’s story compelling, as told through the back and forth correspondence, wrangling with the federal government. Obviously, her memory was failing as she struggled to remember certain facts, at one time stating Henry was a Private and Express Rider, and in another statement he was a Lieutenant (big difference!). I also felt her pain. Why is that?

I felt her pain and more than likely her frustration. It made me think of what we as genealogists go through to find the ABSOLUTE proof required to prove so-and-so is our ancestor. In regards to the absolute proof I had been looking for, one of the documents listed William and Sarah’s children — Mary Ann among them. She lived in an age where there was no such thing as “instant” anything in terms of vital information. Sarah, her attorney and her family persisted, however, until they were successful. And, so must we all. As I always like to say — KEEP DIGGING!

Thanks for stopping by! For more stories like this one, consider subscribing to Digging History Magazine. Purchasing a subscription entitles you to subscriber benefits (20% off all services, including custom-designed family history charts) AND a chance to win your very own custom-designed family history chart! Details here (or click the ad below).

Thanks for stopping by! For more stories like this one, consider subscribing to Digging History Magazine. Purchasing a subscription entitles you to subscriber benefits (20% off all services, including custom-designed family history charts) AND a chance to win your very own custom-designed family history chart! Details here (or click the ad below).

Footnotes:

The Civil War in Missouri: A Border State Torn Asunder

The latest issue of Digging History Magazine is out and available by single issue purchase or subscription (three budget-minded options). This issue, the final issue of 2025, features the “Show Me State” of Missouri, its history and how to find the best historical and genealogical records. Among the featured articles is an extensive one, entitled “The ‘Wild West’ of the Civil War: A Border State Torn Asunder”. Here is a short excerpt from the article, created using AI Text to Speech technology.

Other articles featured in this issue include:

Other articles featured in this issue include:

- Mining Genealogical Gold: Finding Historical Missouri Records (and the stories behind them)

- Going to War Over Heaven on Earth: Regulating the Mormonites in Missouri

- Essential Tools for the Successful Family History Researcher

- Adventures in Research: What Happened to Stephen Paul?

This issue features over 100 pages of Missouri history, as well as tips for finding the best records (many of them absolutely free!) — no ads, just stories and great tips! Purchase it by clicking here.

To learn more about the digital magazine and the services offered by Digging History, see this special promotional page which provides information about the chance to win a custom-designed family history chart: https://digging-history.com/dhmpromo/

Playing in My New “Sandbox”

I really shouldn’t be playing around with this new technology right at this moment, since I really need to finish the last issue of Digging History Magazine for 2025. I’m getting close though, just a few more pages to write. A few days ago I posted a sample of AI Text to Speech technology, and I’m slowly learning some (but not all) of the ins-and-outs. Today’s post features a short article written for the Arkansas issue (published recently).

I really shouldn’t be playing around with this new technology right at this moment, since I really need to finish the last issue of Digging History Magazine for 2025. I’m getting close though, just a few more pages to write. A few days ago I posted a sample of AI Text to Speech technology, and I’m slowly learning some (but not all) of the ins-and-outs. Today’s post features a short article written for the Arkansas issue (published recently).

It’s a story taken directly from my Hall family heritage (the Rupe line). My grandfather, Hulon Hall, was born in Magazine (Logan County), Arkansas and his mother’s family (the Rupes), lived in neighboring Sebastian County. This is a story from the Civil War, followed by a family tragedy several years later. I hope you enjoy it!

Thanks for stopping by! For more stories like this one, consider subscribing to Digging History Magazine. Purchasing a subscription entitles you to subscriber benefits (20% off all services, including custom-designed family history charts) AND a chance to win your very own custom-designed family history chart! Details here (or click the ad below). Questions? Contact me: [email protected].

Thanks for stopping by! For more stories like this one, consider subscribing to Digging History Magazine. Purchasing a subscription entitles you to subscriber benefits (20% off all services, including custom-designed family history charts) AND a chance to win your very own custom-designed family history chart! Details here (or click the ad below). Questions? Contact me: [email protected].

Ralph Waldo Emerson Said it Best: Try Something New

Ralph Waldo Emerson said it best: “All life is an experiment. The more experiments you make the better.”

I’ve been wanting to try this and now seemed like a good time to give it a test run. Using Text to Speech AI technology, here’s a snippet from the soon-to-be-published last issue of 2025 (a bit behind schedule) which features the “Show Me State” of Missouri. The issue will feature articles highlighting the state’s history and how and where to find the best genealogical and historical records. This is an excerpt from an article entitled: “Adventures in Research: What Happened to Stephen Paul?”

I still need to work the bugs out and have a lot to learn I’m sure, but would love to know what readers/listeners think. Leave a comment below or email me at [email protected].

History in the Raw: The Importance of Diaries, Journals and Letters in Genealogical Research

“History in the raw” is how the National Archives refers to “documents – diaries, letters, drawings, and memoirs – created by those who participated in or witnessed the events of the past – tell[ing] us something that even the best-written article or book cannot convey.”4 These historical documents are also among the most valuable resources genealogists can utilize to unravel the mysteries of family history.

“History in the raw” is how the National Archives refers to “documents – diaries, letters, drawings, and memoirs – created by those who participated in or witnessed the events of the past – tell[ing] us something that even the best-written article or book cannot convey.”4 These historical documents are also among the most valuable resources genealogists can utilize to unravel the mysteries of family history.

Locating these historical records is pure “genealogical gold” in many cases. Letters, diaries, journals or memoirs can often go a long way in proving (or dispelling) the various family “legends and lore” – depending on how lucidly (and honestly) one’s ancestor recorded their own history, that is.

According to Merriam-Webster, the word “diary” derives from the Latin word “dies” for “day”.6 The word “diary” is often used interchangeably with “journal”, “journaling” being a common term used today. Either way, these are instruments a person utilizes to record daily events and one’s thoughts and personal reflections.

Like most everything around us, diaries have a history, a long one. One of the earliest references to making regular entries in a diary goes back to the second century when Marcus Aurelius, philosopher and Roman Emperor (A.D. 161-180) recorded “a series of spiritual exercises filled with wisdom, practical guidance, and profound understanding of human behavior”, according to the Amazon.com description.

The first reference to the term “diary” occurred in the early seventeenth century, around the time settlers began arriving on the shores of what one day would become America. Evidence of our forefathers recording their experiences is found in journals, like the one written by William Bradford, Of Plymouth Plantation (1630-1651).

As far as Mayflower history is concerned, his writings, first published in 1854, are considered to be the most complete first-hand account of the Pilgrims’ early years. If you have Mayflower ancestors, find a copy of Bradford’s journal and learn exactly what life was like. In it you will also find the real story of Thanksgiving.

Diaries and journals were more regularly utilized by men in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries to record matters related to business concerns. For men like George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, keeping a record of daily weather and how it affected their agricultural interests was a vital daily routine. Even when Washington was away from his Mount Vernon plantation he still received a weekly summary of weather conditions. His overseer made sure he received those reports in a timely manner so he could judge how the weather was affecting his crops.

In late January of 1772, George Washington was home and witnessed an epic storm, known now as “The Washington and Jefferson Snowstorm of 1772”, with his own eyes. His weather diary entries read like this:

January 27, 1772, “At home by ourselves, with much difficulty rid as far as the mill, the snow being up to the breast of a tall horse everywhere. Snowed all day. 28 – north wind, very cold, snow drifted in high banks three feet deep everywhere. 29 – Sun shone in morning, but by eleven o’clock it clouded up and snowed all night and then turned to rain.”7

How accurate was George Washington’s account? The Maryland Gazette confirms the observations of the future president:

The Winter here has been in general very mild until Sunday Evening last, when it began to snow, which continued without Intermission until Tuesday Night. Yesterday Morning we had again the appearance of fine moderate weather, but in the Evening it began again to snow very fast, which continued all the Night; ‘tis supposed the Depth where it has not drifted, is upwards of Three Feet, and it is with the utmost Difficulty People pass from one House to another. The Quantity of Snow has also chilled the Water to such a Degree, that though the Frost has been severe for these few Days past, yet our Navigation is entirely stopped up by the Ice.8

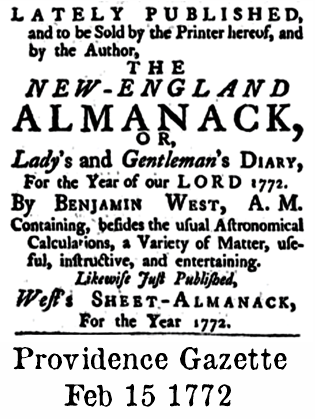

Perhaps Washington used something referred to as a diary which was more like an annual almanac.

Letts of London, founded in 1796 by John Letts, lays claim to this day for publishing the world’s first known commercial diary. In 1812 Letts combined a journal with a calendar, and voilà there was a convenient way to record one’s thoughts on a daily basis, year after year. In the nineteenth century millions of their diaries were sold. The company touted the “Real Value of a Diary”:

Letts of London, founded in 1796 by John Letts, lays claim to this day for publishing the world’s first known commercial diary. In 1812 Letts combined a journal with a calendar, and voilà there was a convenient way to record one’s thoughts on a daily basis, year after year. In the nineteenth century millions of their diaries were sold. The company touted the “Real Value of a Diary”:

Use your diary, we say, with the utmost familiarity and confidence; conceal nothing from its pages, nor suffer any other eye than your own to scan them. No matter how rudely expressed, or roughly written, or with what material, let nothing escape you that may be of the slightest value hereafter, even though it be but to form a simple link in the daily chain of common transactions. If you receive a trivial commission a diary can be more safely entrusted with it than your unaided memory, and one word is often a sufficient memorandum to render it intelligible.9

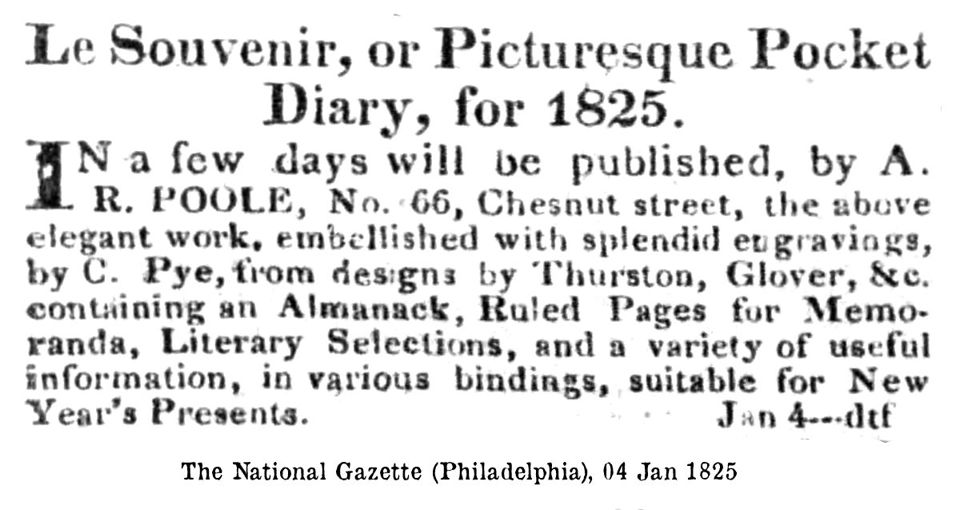

While prior to the 1800s diaries and journals were more often utilized by men, as the price of paper decreased and literacy rates rose, women also began to keep diaries and journals. American stationers began publishing their own version of annual diaries. An advertisement for a “picturesque pocket diary” appeared in a Philadelphia newspaper in early 1825, promoted as a suitable New Year’s present.

Around this time private diaries began to be published, one of the first being the diary of John Evelyn (1620-1706) who wrote of life in 17th century England. The book’s preface lays out the importance of Evelyn’s work (two volumes, over 400 pages), and even the less-than-lofty accounts of any of our ancestors who ever sat down and put pen to paper to record their personal thoughts. It also emphasizes the importance of history in genealogical research:

Of all the aids to a complete comprehension of the political, moral, social, or racial changes, evolutions, upheavals and schisms that make what we call History, the Memoirs of each epoch studied are by far the most valuable. Memoirs may be called the windows of the mind. In the privacy of the boudoir or of the study, men and women will inscribe upon the pages of their journals in terse and unaffected language their real thoughts, motives and opinions, unrestrained by the calls of diplomacy or self-interest.10

Even if you don’t have access to an ancestor’s journals or diaries, you may be able to glean historical context from the pages of a contemporary, someone who lived during a particular era or in the same locality as your ancestor. There are a number of ways to access these types of accounts, especially online. To learn more about those resources and read the remainder of the article, purchase the issue here.

Thanks for stopping by! For more stories like this one, consider subscribing to Digging History Magazine. Purchasing a subscription entitles you to subscriber benefits (20% off all services, including custom-designed family history charts) AND a chance to win your very own custom-designed family history chart! Details here (or click the ad below). Questions? Contact me: [email protected].

Thanks for stopping by! For more stories like this one, consider subscribing to Digging History Magazine. Purchasing a subscription entitles you to subscriber benefits (20% off all services, including custom-designed family history charts) AND a chance to win your very own custom-designed family history chart! Details here (or click the ad below). Questions? Contact me: [email protected].

Footnotes:

Looking Ahead to 2026: Mining Genealogical Gold and Exploring Our American Heritage

2026 is upon us! As I continue working on the last issue of Digging History Magazine for 2025, featuring the “Show Me State” of Missouri (it’s a bit behind schedule, but it’s coming!), I’ve already scheduled the 2026 lineup as I continue a series focusing on American historical and genealogical research.

Each issue is filled with stories about events which shaped the state’s history, as well as tools and tips for finding the best historical and genealogical records. Contrary to what some might assume, many of those records are absolutely FREE — you just have to know where to find them! Each of these state issues features a regular (and extensive) column entitled, “Mining Genealogical Gold: Finding Historical [State] Records (and the stories behind them)”. Not only will you receive valuable tips for finding those records, but I accompany them with a brief state history and stories about those records to hopefully inspire you to “keep digging”.

In 2025 Digging History Magazine featured the following: Rhode Island and Connecticut (Issue 1); New Jersey (Issue 2); Colorado (Issue 3); Oklahoma (Issue 4), Arkansas (Issue 5) and soon-to-be-published Missouri (Issue 6).

In 2026 the following states will be featured (in this order): Nebraska (Issue 1); Iowa (Issue 2); Illinois (Issue 3); Indiana (Issue 4); Ohio (Issue 5); and Pennsylvania (Issue 6). I look forward to researching and writing about these states and uncovering the stories which shaped their history — and finding the records which will assist in uncovering more about our ancestors.

I also plan to continue publishing at least one blog article a week. With all the time I spend researching, writing and editing the magazine (plus working on client research and chart projects), I’m quite busy, but still want to stay in touch. Just so you don’t miss one, be sure and subscribe to the blog (on the right-hand side of the page).

Also I would love to hear from my readers, especially if they have stories of their own to share. You never know — your story might inspire an article . . .stay tuned!

If you love history, or perhaps you would like to begin exploring your family history and don’t know how to begin, consider subscribing to Digging History Magazine. Purchasing a subscription (three budget-friendly options) entitles you to subscriber benefits (20% off all services, including custom-designed family history charts) AND a chance to win your very own custom-designed family history chart! This promotion also includes receiving 10 FREE ISSUES! Details here (or click the ad below). If you need assistance or have questions, please feel free to contact me directly: [email protected].

If you love history, or perhaps you would like to begin exploring your family history and don’t know how to begin, consider subscribing to Digging History Magazine. Purchasing a subscription (three budget-friendly options) entitles you to subscriber benefits (20% off all services, including custom-designed family history charts) AND a chance to win your very own custom-designed family history chart! This promotion also includes receiving 10 FREE ISSUES! Details here (or click the ad below). If you need assistance or have questions, please feel free to contact me directly: [email protected].

OK, I give up . . . what is it?

From time to time I run across an unfamiliar term while researching family history. Having a natural curiosity, I feel compelled to learn more about it — and sometimes that turns into quite a research foray all its own. Such was the case of discovering what the term “grass widow” meant. It turned out to be quite the research adventure! From an extensive article published in the September-October 2021 issue of Digging History Magazine, here is an excerpt:

As genealogists we have all come across terms which are unfamiliar for one reason or another. Many times the word or terminology is obsolete, or it might mean something altogether different in the twenty-first century.

As genealogists we have all come across terms which are unfamiliar for one reason or another. Many times the word or terminology is obsolete, or it might mean something altogether different in the twenty-first century.

Grass Widow

I don’t remember exactly the circumstances of how or when I came across the term “grass widow”. It was certainly a curious term and I was not at all acquainted with what the term meant. A little research was in order, especially after I found references to the term in both newspapers and census records. As is often the case there are stories to be told, but first a definition is in order.

The term “grass widow”, according to Merriam-Webster, was first used circa 1699. In terms of usage, Merriam-Webster provides a two-tiered definition, suggesting the term dates back to the late 17th century. In those days “grass-widow” meant either “a discarded mistress” or “a woman who has had an illegitimate child.” Thereafter, the term may still have implied some sort disreputable behavior, but it also came to mean “a woman whose husband is temporarily away from her” or “a woman divorced or separated from her husband”.11 Any of those definitions could be construed as untoward in one way or another.

However, the Oxford English Dictionary suggests the term dates back to the 16th century. Either way, the earliest definition of “grass widow” carried a certain disreputable stigma. In a Grammarphobia blog article, entitled “Grass widow or grace widow?”, the writers attempt to determine whether there is a distinction between “grace widow” and “grass widow”. The Oxford English Dictionary suggests “grass widow” is a corruption of “grace widow”, although it does not in fact provide a definition for “grace widow”. It is a rather muddled argument either way.

Perhaps the distinction was best defined, as cited in the blog article, by a letter to the editor in an 1859 issue of Ladies Repository, a Methodist magazine:

GRASS-WIDOW – The epithet is probably a corruption of the French word grace – pronounced gras. The expression is thus equivalent to femme veuve de grace, foemina vidua ex gratia, a widow, not in fact but – called so – by grace or favor. Hence, grass-widow would mean a grace widow: one who is made so, not by the death of her husband, but by the kindness of her neighbors, who are placed to regard the desertion of her husband as equivalent to his death.12

Later versions of the Oxford English Dictionary suggested that “words for grass and straw ‘may have been used with opposition to bed.’ So a “grass widow” might provide a roll in the hay, so to speak – an illicit sexual tryst, not necessarily in a bed.”13 However, the blog authors suggested that by the mid-nineteenth century the term “grass widow” had become less derogatory and generally meant a woman’s husband was away. If you’re researching family history and you come across the term, perhaps in a census record, you will need to determine what “away” really meant. Was the husband working elsewhere? Had he run off and left his family to fend for themselves (or ran off with another woman)? Was he perhaps away at war, or had there been a divorce?

I recently came across an indirect reference to “grass widow” while reading The Taking of Jemima Boone, by Matthew Pearl. The book covers the kidnapping of Daniel Boone’s daughter, Jemima, as well as quite a ride through early Kentucky history. According to Pearl, with Daniel away for long stretches, her birth carried a certain question mark:

For the Boone family, Daniel’s long absence evoked many earlier stretches away from home, both planned and unplanned, including one that, according to community lore occurred almost sixteen years before. That time, months had stretched into nearly a year before Daniel reappeared after a “long hunt.” Memories and anecdotes about the timing of that absence plagued the family thereafter. By the time Daniel reappeared – so variations of the story went – Rebecca had conceived a child, gone through a pregnancy and given birth to their fourth child, Jemima. . . .

Rumors posited that the long-absent Daniel could not have been little “Mima’s” father, and that her biological father, to compound matters, was really one of Daniel’s brothers, Squire or Ned. By one account, when told the truth by a remorseful Rebecca, Daniel shrugged and commented that his child “will be a Boone anyhow.” Some remembered Daniel laughing over the years about the rumor, in the process tacitly admitting to it. In some versions, Rebecca felt light embarrassment over the topic – sitting knitting with her “needles fly[ing]” when it came up in conversation with visitors – while in other accounts, Rebecca ribs Daniel that if he’d been home, he could have avoided the problem.14

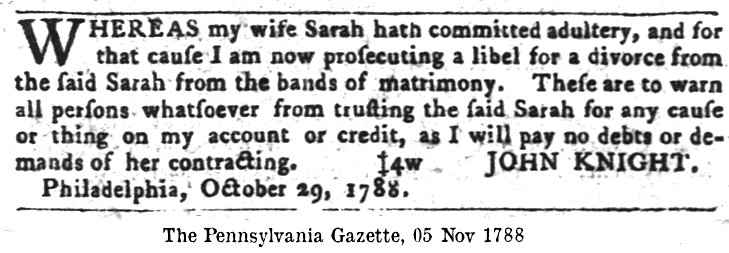

Was Rebecca Boone a “grass widow”? Perhaps, but Daniel always came home – eventually. Still, in the eighteenth century men could divorce their wives for adultery.

Whether it was the husband divorcing the wife or vice versa, breaking the “bands of matrimony” was stigmatized, and in the 18th century not necessarily an easy thing to obtain. Some have suggested a grass widow was a divorcee and perhaps it was kinder for her community to refer to her as a grass widow. . . .

For more discussion (and anecdotal evidence) on this topic (including the husbands who contracted “gold fever” in the mid-1800s) and to read the rest of this extensive article, purchase the issue here.

![]() Thanks for stopping by! For more stories like this one, consider subscribing to Digging History Magazine. Purchasing a subscription entitles you to subscriber benefits (20% off all services, including custom-designed family history charts) AND a chance to win your very own custom-designed family history chart! Details here (or click the ad below).

Thanks for stopping by! For more stories like this one, consider subscribing to Digging History Magazine. Purchasing a subscription entitles you to subscriber benefits (20% off all services, including custom-designed family history charts) AND a chance to win your very own custom-designed family history chart! Details here (or click the ad below).

Footnotes:

How Did Our Early American Ancestors Celebrate Christmas?

Today we celebrate Christmas with elaborate lighting displays, gifts and gadgets, and over-stuffing ourselves with Christmas goodies. Of course, those traditions have evolved with the changing culture and technology. Our ancestors, however, brought very different traditions to America.

Today we celebrate Christmas with elaborate lighting displays, gifts and gadgets, and over-stuffing ourselves with Christmas goodies. Of course, those traditions have evolved with the changing culture and technology. Our ancestors, however, brought very different traditions to America.

The first colonists to introduce celebration and merriment to the holiday were the first settlers of Virginia. The traditions they brought would likely have been reflected in a sixteenth century poem by Thomas Tusser:

At Christmas play and make cheer

For Christmas comes but once a year

Good bread and good drink, a good fire in the hall

Brawn, pudding and souse, and good mustard withall;

Beef, mutton and pork, shred pies of the best;

Pig, veal, goose and capon and turkey well drest;

Cheese, apples and nuts, jolly carols to hear,

As then in the country is counted good cheer.

One tradition brought by the English colonists of Virginia was noise-making with horns, drums and fireworks, which had been introduced in England in the fifteenth century. In 1486 the first fireworks display took place in celebration of King Henry VII’s marriage. This tradition continues in the South even today.

In Williamsburg, the Yule log, the foundation of the traditional Christmas Eve fire, was lit and carols were sung. The Yule log offered a respite of sorts for the colonists, since as long as it burned no one had to work. One could imagine them going to great lengths to keep the fire going! On Christmas Day, everyone attended church services, followed by a feast, dances, games and fireworks — all of this merriment sometimes continuing until the new year. Contrast that, however, with the Puritans of Massachusetts.

Merriment was not much on the minds of the Puritans, going so far as to declare the holiday celebration illegal. Christmas, strictly considered a religious event only, was a holy day to be celebrated without pagan rituals. By the time of the Revolutionary War, restrictions began to be loosened, although Massachusetts did not recognize Christmas as a legal holiday until 1856.

Merriment was not much on the minds of the Puritans, going so far as to declare the holiday celebration illegal. Christmas, strictly considered a religious event only, was a holy day to be celebrated without pagan rituals. By the time of the Revolutionary War, restrictions began to be loosened, although Massachusetts did not recognize Christmas as a legal holiday until 1856.

When did St. Nicholas introduce himself to America? That would be via the Dutch. On Christmas Day of 1624 members of the Dutch East India Company landed on what we now know today as Manhattan Island and made merry. As more settlers arrived from Holland, they brought with them their customs of St. Nicholas, bearer of gifts, and stockings filled with goodies. The Dutch also believed the celebration was meant to bring families closer together.

Swedes settled in Delaware in 1638, whence came the tradition of hanging a pine or fir wreath on the door of one’s home — a sign of both welcome and good luck. Instead of St. Nicholas, their tradition was gift-giving elves.

The seventeenth century brought some of the first German colonists and with them the tradition of decorating an evergreen tree with ornaments, candles and cookies. As the country expanded its borders beyond the original thirteen colonies, the French and Spanish would put their indelible mark on the Christmas holiday.

The French would attend a midnight mass on Christmas Eve and then partake of a special meal called a réveillon. Children left their shoes by the crèche hoping to find them filled with gifts from baby Jesus the following morning. For the French, Christmas was a time of peace and

reflection, followed by a New Year’s Eve celebration of parades and masquerade balls. Today, the tradition of réveillon is still observed in New Orleans.

The Spanish who settled throughout the Southwest brought their tradition of re-enacting Joseph and Mary’s journey on the first Christmas, called Las Posadas. Included in the festivities was the tradition of children striking a piñata filled with toys and sweets. One of the more beautiful symbols of the Christmas season in the Southwest, seen today especially in New Mexico, is the lighting of luminarias or farolitos. Spanish traders may have originally introduced this custom because of the fascination with a long-time Chinese tradition of paper lanterns, according to Pedro Ribera Ortega, author of Christmas In Old Santa Fe.

Clement C. Moore’s poem, A Visit From St. Nicholas (later named ‘Twas The Night Before Christmas), is thought to have been responsible for introducing the concept of Santa Claus in America, perhaps a melding of several traditions. Moore, a professor of Oriental and Greek literature, is said to have been reluctant at first to acknowledge authorship of something he considered “less than scholarly”. He had written it for his children, but a friend submitted it for publication in 1823.

By the 1860s the celebration of Christmas with gift giving, Santa Claus and decorated trees was common throughout the country, and by the Victorian Age such traditions as kissing under the mistletoe had been introduced. Tree ornaments began to be commercially produced in the 1870’s.

Hanukkah

America is a Judeo-Christian nation and I would be remiss if I didn’t mention the Jewish tradition of Hanukkah. It is not considered one of the major holidays that people of the Jewish faith celebrate every year, but the history of the holiday in America is interesting. In 1860 two Cincinnati rabbis started a movement to “Americanize” Judaism. Included in their plans was a way to create a fun festive holiday for Jewish children to engender excitement about their faith. The rabbis wanted Jewish children to “have a grand and glorious Hanukkah, a festival as nice as any Christmas, with songs, dramatics, candle lighting, ice cream, candy and candy.”

The holiday had previously been more of an adult observance of the re-dedication of the Second Temple during the time of the Maccabean Revolt of 2nd century B.C. The holiday is determined by the Hebrew calendar and can fall anywhere between late November and late December. Hanukkah is observed for eight successive nights and each night another branch of the menorah is lit, followed by food (preferably fried foods like potato cakes and doughnuts) and games. One tradition especially geared toward children is the dreidel, a four-sided spinning top, each side with a Hebrew letter which altogether spell out “A great miracle happened here.”

The holiday had previously been more of an adult observance of the re-dedication of the Second Temple during the time of the Maccabean Revolt of 2nd century B.C. The holiday is determined by the Hebrew calendar and can fall anywhere between late November and late December. Hanukkah is observed for eight successive nights and each night another branch of the menorah is lit, followed by food (preferably fried foods like potato cakes and doughnuts) and games. One tradition especially geared toward children is the dreidel, a four-sided spinning top, each side with a Hebrew letter which altogether spell out “A great miracle happened here.”

America’s year-end holiday season is filled with all kinds of history and meaning. Of course, what we all should look forward to is not the gadgetry and gift-giving, but spending time with family and making memories, don’t you think?

Thanks for stopping by! For more stories like this one, consider subscribing to Digging History Magazine. Purchasing a subscription entitles you to subscriber benefits (20% off all services, including custom-designed family history charts) AND a chance to win your very own custom-designed family history chart! Details here (or click the ad below).

Thanks for stopping by! For more stories like this one, consider subscribing to Digging History Magazine. Purchasing a subscription entitles you to subscriber benefits (20% off all services, including custom-designed family history charts) AND a chance to win your very own custom-designed family history chart! Details here (or click the ad below).

Footnotes:

The Pitfalls of Genealogical Research (gold mine or land mine?)

From the July-August 2022 issue of Digging History Magazine, an extensive article regarding the pitfalls of genealogical research. Sometimes what we uncover can be potentially shocking or devastating . . . here is an excerpt:

If you’ve been researching family history for awhile, it’s possible you, like me, have come across unexpected – or perhaps even shocking – information about one or more of your ancestors. How should we respond? Do we freely share the information or hide it away? Of course, our response may depend on what we uncovered.

If you’ve been researching family history for awhile, it’s possible you, like me, have come across unexpected – or perhaps even shocking – information about one or more of your ancestors. How should we respond? Do we freely share the information or hide it away? Of course, our response may depend on what we uncovered.

I’d have to say some of the most shocking examples I’ve uncovered for clients is something no family member may want to ever talk about, especially if it’s part of recent family history. For an understandably good reason it’s often swept under the rug, although I uncovered a family tree at Ancestry which is the most mind-blowing example I’ve ever seen. These types of situations are extremely painful, and genealogically-speaking, can potentially complicate a family tree no matter how long ago it occurred. You might discover it in a contemporary newspaper clipping or in early colonial church records.

Incest

Dating back to Biblical times, incest, generally defined as having sexual relations with a person too closely related, was considered one of the most egregious sins, punishable in certain cases by death (Leviticus 20). Because the majority of articles in this publication focus on American history, let’s fast forward to the nation’s early colonial era and how our ancestors dealt with incest – was it a sin or a crime (or both)?

Most early American colonists were British subjects, so it’s no surprise the laws they adopted were largely based on, although not entirely identical to, English Common Law. However, each colony was governed independently and its laws were therefore different despite being based on English Common Law.

For example, while you won’t find mention of “incest” in early Massachusetts colonial laws, evidence suggests the government still had authority to pass laws regulating incestuous marriages. In 1670 the Court of Assistants, Massachusetts’ highest court of original jurisdiction, ruled it was unlawful for a widower to marry his deceased wife’s sister. Several other egregious acts were covered in early colonial laws, so why wasn’t the sin/crime of incest addressed?

According to a Columbia University Law School scholarly paper, “Incest in Colonial Massachusetts: 1636-1710”:

Colonial Massachusetts maintained a civil government system that was separate from the Puritan church, and yet, because of the colonists’ strong Puritan beliefs, the church exercised enormous influence on the colonial government’s laws and policies. The result of this societal organization was the blurring of church and state; of crimes and sins. Incest is an example of an offense that was considered a crime because it was a sin. . . .

In the English system, religious ecclesiastical courts had jurisdiction over marriage. Massachusetts broke with England, as marriage in colonial Massachusetts was a civil matter. While marriage was a civil matter in colonial Massachusetts, both existing English law and Puritan beliefs largely dictated what incestuous-marriage laws the civil government adopted. . . .

How colonial Massachusetts treated incest (in both its forms) was heavily influenced by Puritanism, which was a driving force in the establishment of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. The colony relied on a theory of social covenant to demand that everyone “live righteously and according to God’s word.”13

Puritanism was founded on the idea that one’s “thoughts and deeds serve God.” Marriage was considered a form of “outward conduct”, and thus a way to serve God. And, because Massachusetts was founded by Puritans, the colonial government was serious about deciding who could marry whom, meaning they could regulate against incestuous marriages. Not surprising, those laws were influenced by scripture, as well as existing English law. . . .

[continued in article, purchase issue here]

The Potential Perils of DNA Testing

This particular “Oh, Dear!” scenario is a recent one, especially given the widespread use of DNA testing in genealogical research. Granted, some people sign up and take these tests, utilizing either a test tube of saliva or a cheek swab, just to find out what they assume will be fun facts, e.g., their ethnicity and ancient ancestral roots. You will find multiple instances of these types of results and many will never have started a family tree on sites like MyHeritage, Family Tree DNA or Ancestry.

Did they just want to know ethnicity, or did they find something disturbing and decided not to pursue it? Both are possibilities, but there are many stories of people who decide to plow ahead and uncover family secrets. A recent Reader’s Digest article highlights a few recent developments:

● Writing in MSN’s The Moneyist column, a man told the story that after years of receiving substantial monetary gifts from a wealthy uncle, a 23andMe DNA test revealed that he was actually the uncle’s biological son. The family secret was confirmed by the man’s mother, who had worked as the Chief Financial Officer for the company the “uncle” ran.

● When Alice Collins Plebuch decided to do a DNA test, she did it all in good fun. As originally reported by the Washington Post, the woman, who identified as Irish American, was shocked to find a mix of European Jewish, Middle Eastern, and Eastern European genes in her results. After family-wide DNA testing, she learned that her father was not the biological son of her grandparents. After even more digging, Plebuch finally got to the bottom of the story: Her father had been sent home with the wrong family. A mystery of over 100 years had been solved by a mail-in DNA test. . . .

Examples such as these can potentially be disturbing and heartbreaking, in some instances tearing a family apart with divorce. Whether or not an unexpected DNA result leads to such devastating consequences, many are seeking support from others who have discovered similar “family secrets”. One private Facebook group, DNA NPE (“Not Parent Expected”) Friends is one such entity which seeks to connect people whose lives have been changed after receiving their test results. . . .

[continued in article, purchase issue here]

Yet another “moral dilemma” of our rapidly changing world, is artificial insemination, aka “test tube baby”. For more discussion on this issue and to read the entire article, complete with more examples and resources, purchase the issue here.

Thanks for stopping by! For more stories like this one, consider subscribing to Digging History Magazine. Purchasing a subscription entitles you to subscriber benefits (20% off all services, including custom-designed family history charts) AND a chance to win your very own custom-designed family history chart! Details here (or click the ad below).

Thanks for stopping by! For more stories like this one, consider subscribing to Digging History Magazine. Purchasing a subscription entitles you to subscriber benefits (20% off all services, including custom-designed family history charts) AND a chance to win your very own custom-designed family history chart! Details here (or click the ad below).

Footnotes:

Researching “Family Lore” — It’s Tricky

So-called “family lore” has no doubt enticed any number of genealogists (or would-be genealogists) into discovering more about their family history. That may be a great impetus to begin “digging”, but how many of us bother to take the time to RESEARCH the “family lore” — or do we just begin our research by finding “hints” which support that fantastic story you’ve heard all your life. In my experience that leads to a lot of “twisted trees (branches, vines and so on)” which make it difficult to actually VERIFY (or DISPROVE) the oft-told tale. Such was the case recently for me.

While writing the “Mining Genealogical Gold” article for the Digging History Magazine issue featuring Arkansas, I discovered a clue I had never seen (or paid attention to) — and it totally disproved the lore (at least a portion of it) which has been recited many times over. I can’t believe I missed it! The database was All Arkansas, U.S., Compiled Marriages from Select Counties, 1779-1992 at Ancestry. Here’s what I wrote:

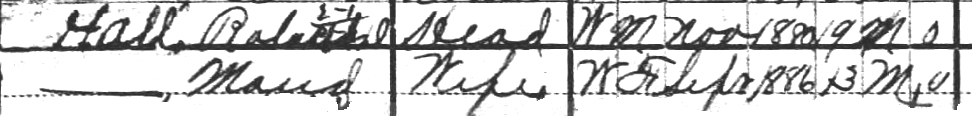

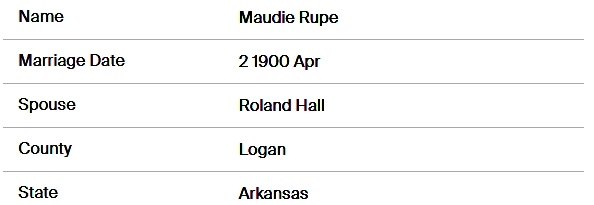

By searching this database I discovered one particular fact about which I had been misled by “family lore” I guess you would say. My great grandparents, Roland Hall and Maude Rupe (William and Mary Ellen’s daughter), were always said to have snuck off to Mena, the county seat of Polk County, Arkansas, ostensibly because Maude was actually a bit young in 1900. Here is the oft-repeated story (which I will now have to correct!):

Maude Rupe was born September 11, 1886 in Sebastian County, Arkansas to parents William Marion and Mary Ellen (Cochrell) Rupe. She was a fetching young girl who caught the eye of Roland Daniel Hall, my great grandfather. Roland Daniel was born on November 8, 1880 in neighboring Logan County to parents John Clayton and Kate Hall (John and Kate were first cousins).

Maude Rupe was born September 11, 1886 in Sebastian County, Arkansas to parents William Marion and Mary Ellen (Cochrell) Rupe. She was a fetching young girl who caught the eye of Roland Daniel Hall, my great grandfather. Roland Daniel was born on November 8, 1880 in neighboring Logan County to parents John Clayton and Kate Hall (John and Kate were first cousins).

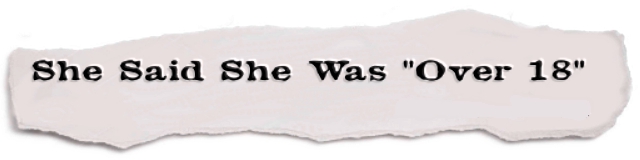

When Roland and Maude decided to get married, they took a little trip south to Mena, the county seat of Polk County. I’m sure they did that to avoid running into anyone who could attest to the fact that young Maude wasn’t quite yet fourteen years old on April 2, 1900. In fact, she was seven months and nine days short of her fourteenth birthday. Roland, nineteen, was about to marry a thirteen year-old girl. According to the marriage affidavit, Maudie Rupe had arrived at the age of 16 years. The story she told for years thereafter, however, was that she swore to be over the age of eighteen. Maude had written the number “18” on a scrap of paper and slipped it into her shoe. When asked if she was “over the age of 18” she emphatically answered, “Yes, I am!”

The newlyweds moved to Yell County and on June 25 were enumerated there for the 1900 census. My great grandmother apparently deemed it imprudent to try and fool the federal government — her age was listed as 13.

My dad remembered the numerous times that his grandparents sat at their kitchen table, told that story and laughed about it. Now it’s part of our family lore, and even those who never met them have something to remember about our ancestors Roland Daniel Hall and Maude Rupe.

While perusing this database, I also found their marriage record and it clearly states Logan County – I can’t believe I missed that!

Family history will now be “re-written”! Let that serve as a lesson – research your “family lore” (and keep an open mind)!

Thanks for stopping by! For more stories like this one, consider subscribing to Digging History Magazine. Purchasing a subscription entitles you to subscriber benefits (20% off all services, including custom-designed family history charts) AND a chance to win your very own custom-designed family history chart! Details here (or click the ad below).

Thanks for stopping by! For more stories like this one, consider subscribing to Digging History Magazine. Purchasing a subscription entitles you to subscriber benefits (20% off all services, including custom-designed family history charts) AND a chance to win your very own custom-designed family history chart! Details here (or click the ad below).