A group of well-to-do young ladies, anxious to do their part for the Southern cause, formed and all-female cavalry unit in 1862, calling themselves the Rhea County Spartans. These “sidesaddle soldiers” were like many women on both sides of the war who wished with all their hearts they could do something to lend support (if only they were men!).

A group of well-to-do young ladies, anxious to do their part for the Southern cause, formed and all-female cavalry unit in 1862, calling themselves the Rhea County Spartans. These “sidesaddle soldiers” were like many women on both sides of the war who wished with all their hearts they could do something to lend support (if only they were men!).

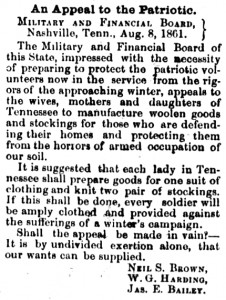

Instead, these women formed Soldier’s Aid Societies. In fact, some believe that “Spartans” may not have been the original name. On the Rhea County Spartans Facebook page, contributor Tom Robinson points out that many of the same young women were members in 1861 of the Rhea County Soldier’s Aid Society. The name “Spartans” seems a bit militant to me and there’s no evidence these women participated in any military operations, unlike some women (see yesterday’s book review of Liar, Temptress, Soldier, Spy) who actually disguised themselves as men.

More than likely they were influenced by patriotic appeals like this one which appeared in the August 16, 1861 issue of the Athens Post:

As the story goes, these young women decided to form their own cavalry in Rhea County (pronounce ray), Tennessee to support the Confederate cause. Despite the fact that much of eastern Tennessee was pro-Union, Rhea County chose the other side to rally behind. Following the state’s vote for secession in June of 1861, Rhea County formed seven companies for the Confederate Army and only one for the Union.

As the story goes, these young women decided to form their own cavalry in Rhea County (pronounce ray), Tennessee to support the Confederate cause. Despite the fact that much of eastern Tennessee was pro-Union, Rhea County chose the other side to rally behind. Following the state’s vote for secession in June of 1861, Rhea County formed seven companies for the Confederate Army and only one for the Union.

According to an account in a 1911 Confederate Veteran article, three Confederate companies had been formed in the area, the third in May of 1862 by Captain W.T. Darwin. That summer these young Rhea County ladies “agreed to meet at certain points in that county and go in squads to visit one of these companies, where some of them had fathers, brothers, or sweethearts.”

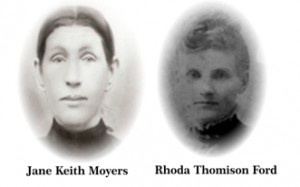

Just for fun they organized a cavalry company complete with officers: Mary McDonald, Captain; Jennie Hoyal, Orpha Jane Locke and Rhoda Thomison, Lieutenants. Some of the other company members included: Kate Hoyal, Mary Keith, Sallie Mitchell, Caroline McDonald, Jane Paine, Mary Robertson, Mary Paine, Mary Crawford, Anne Myers, Mary Ann McDonald and Martha Early.

Barbara Frances Allen, another member of the Spartans, had three brothers serving with General Lee and one with General J.E. Johnston. Her father was in prison. One of Rhoda Thomison’s brothers had been wounded at Shiloh, another killed at Chickamauga and another served with General Lee.

The Spartans visited family members serving in the vicinity of Rhea County, taking supplies, food and clothing. After the fall of Chattanooga in late 1863, their mission may have changed, although there are no official records which provide specific details. Some historians believe they may have engaged in spying after Union forces moved into their county.

The only sliver of possible evidence that might indicate these women did engage in spying, or at least strongly suspected of doing so, was their arrest in April of 1865 just days before the war ended with Lee’s surrender at Appomattox. Union Captain John P. Walker, disdainful of Southern sympathizers, ordered Lieutenant W.B. Gothard to arrest these “dangerous young ladies”. Gothard marched seven of the Spartans from the Thomison home to Smith’s Crossroads, near Walker’s home, where six more girls joined the prisoner group.

Through mud and water, Walker marched the Spartans to Bell’s Landing on the Tennessee River where three more captured members joined them. The Spartans were ordered to board a boat used by the government to haul hay, hogs and cattle, nicknamed the “Chicken Thief”. At gun point the Spartans were ordered to enter a small dining room where they slept on the floor following their exhausting march through muck and mud.

After arriving in Chattanooga, they were marched up to the offices of the provost marshal. When General James B. Steadman was made aware of Walker’s actions he issued a severe reprimand to the captain, believing the bedraggled young ladies presented no threat to the Union. The only requirement for their release was to take an oath of allegiance to the United States. In an article written in 1901 about “Captain” Mary McDonald Sawyers, it was reported that the girls had given Steadman “more than one sample of ‘sass'”. He threatened to send them to Ohio and that’s when they all agreed to take the oath at the urging of “anxious relatives.”

Steadman ordered his adjutant to take them to the Central House and have a sumptuous meal prepared for them. Afterwards they were to be returned to the boat and taken back to Bell’s Landing and escorted home.

By the time they boarded the old boat, word had arrived of General Lee’s surrender. Captain Walker was to escort the young women back to their homes, but he ignored Steadman’s order. Instead, he left them at the landing and the ladies, on their own, made their way back to Rhea County to reunite with their families.

The Spartans disbanded and returned to their more traditional roles as young ladies of the Victorian Age, marrying and raising their children. Although their story faded with the passing of time, history records the Rhea County Spartans were the only female cavalry unit, unofficial though they were, to have served in the Civil War.

The Spartans disbanded and returned to their more traditional roles as young ladies of the Victorian Age, marrying and raising their children. Although their story faded with the passing of time, history records the Rhea County Spartans were the only female cavalry unit, unofficial though they were, to have served in the Civil War.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Great article, thank you.

You’re so welcome and thanks for stopping by!

Hi Sharon. Thank you for this great article. About 25 years ago I bought an ambrotype that shows eight young women and one young man, all sitting on horses in a pose that faces the camera. Inside the case, the following is written in period ink:

This is the ‘Beauregard Cavalry.’ Mr. J. A. Allen was our Captain, to whom this ambrotype belongs. Oh! What delightful times we had. Ah! I must remember. I ought not write here; it will [illegible] it, and no one will ever see it. Farewell Beauregard Cavalry, I hope happy days will ever return.

One of the old members of the ‘B– Cavalry’

When I purchased this image, I asked the dealer (of Civil War antiques) if he knew what this writing meant. He didn’t. Sometime after that, I showed the image to another Civil War antiques dealer, and coincidentally he had actually owned this same ambrotype at one time. He said that he had heard a story that the Beauregard Cavalry was a group of young women who had banded together to do some spying for the Confederacy, and that at one point they had been arrested, but the Federal general in the area actually got angry at his men for arresting these women and ordered them released. However, he said he couldn’t substantiate that story and knew nothing more.

Sometime after that I obtained a copy of the 1911 Confederate Veteran magazine with the article that you referenced. The story in the article matches the story told to me by the antiques dealer, and there’s the consistency of the Allen surname between Barbara, the 1911 article’s author “W.G.” and Captain “J.A.” (I’m not 100% sure that first initial is a “J”, but I think it is) referenced in the case writing. The only thing that’s missing is a use of the name “Beauregard Cavalry”.

I’m wondering if you’ve ever seen this name used in reference to the ladies from Rhea County? I have long hoped to identify who the ladies of the Beauregard Cavalry were and learn their story.

What a fabulous story and piece of history … thanks for sharing! I don’t believe I ran across any references to “Beauregard Calvary”. Do you have any idea where the picture was taken?

Thanks for your reply! Unfortunately I don’t know where the picture was taken. Other than the writing in the case, there are no markings or anything else that I can see which might provide a clue.

I was wondering if what Beauregard had to do with the name, but perhaps in honor of General Beauregard who was in charge of defending Fort Sumter? I haven’t found any specific references to their captain J.A. Allen — that could also have been an “honorary” title and perhaps not a commissioned Confederate officer. It’s a mystery for sure!