Many stories have been written about today’s “feisty female”, but if based on her short autobiography, it’s debatable whether they are true or not. Generally speaking, she was known for her “wild side” and it was legendary, based on the numerous stories in newspapers across the country beginning in the mid-1870s. Legends of America describes her like this:

Many stories have been written about today’s “feisty female”, but if based on her short autobiography, it’s debatable whether they are true or not. Generally speaking, she was known for her “wild side” and it was legendary, based on the numerous stories in newspapers across the country beginning in the mid-1870s. Legends of America describes her like this:

she … [grew] up to look and act like a man, shoot like a cowboy, drink like a fish, and exaggerate the tales of her life to any and all who would listen.

The Encyclopedia Britannica backs up that observation: “The facts of her life are confused by her own inventions and by the successive stories and legends that accumulated in later years.”

Martha Jane Canary, a.k.a. “Calamity Jane” was born near Princeton, Missouri on May 1, 1852 to parents Robert and Charlotte. Martha was the oldest of six children. Her father, a farmer, moved the family to Virginia City, Montana in 1865.

Martha Jane Canary, a.k.a. “Calamity Jane” was born near Princeton, Missouri on May 1, 1852 to parents Robert and Charlotte. Martha was the oldest of six children. Her father, a farmer, moved the family to Virginia City, Montana in 1865.

In her short autobiographical sketch (written for publicity purposes in 1896), Martha wrote (or dictated – she may have been illiterate) that she spent the majority of the five-month trip with the men of the party – she boasted that hunting, scouting and fording streams provided more excitement and adventure. A sampling of her exploits:

Many times in crossing the mountains the conditions of the trail were so bad that we frequently had to lower the wagons over ledges by hand with ropes for they were so rough and rugged that horses were of no use. We also had many exciting times fording streams for many of the streams in our way were noted for quicksands and boggy places, where, unless we were very careful, we would have lost horses and all. Then we had many dangers to encounter in the way of streams swelling on account of heavy rains. On occasions of that kind the men would usually select the best places to cross the streams, myself on more than on occasion have mounted my pony and swam across the stream several times merely to amuse myself and have had many narrow escapes from having both myself and pony washed away to certain death, but as the pioneers of those days had plenty of courage we overcame all obstacles and reached Virginia City in safety.

Her mother died at Black Foot, Montana in 1866, before the family reached its destination, and was buried there. Martha and her remaining family departed sometime during the spring of that year and headed to Utah where she remained until her father died in 1867. She doesn’t mention it in her “memoir” but it’s possible she was in charge of her siblings, being the oldest child. Her life is so sketchy and often misrepresented (primarily by her own account) it’s difficult to determine. In the July-August 2003 edition of the American Cowboy magazine, the article speculates that her siblings were adopted by Mormon families while she began her career as a wild-west drifter.

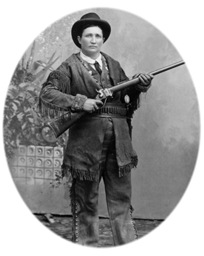

By that time she was an attractive fifteen-year old young woman, who chose to dress in men’s clothes, pulling her hair up under a big hat and further taking on the appearance of a man or older boy. If her own self-proclaimed exploits are to be believed, she worked for the Union Pacific Railroad, an ox cart driver for the Army, wagon train packer and mule skinner. It’s likely she worked whatever job she could find including dishwasher, cook, nurse, and some say prostitute.

After departing Utah, with or without siblings, she headed to Fort Bridger, Wyoming. In 1870 she claimed to have joined up with General Custer’s outfit as a scout. She remarked, “[W]hen I joined Custer I donned the uniform of a soldier. It was a bit awkward at first but I soon got to be perfectly at home in men’s clothes.”

After wintering in Arizona in 1871, she returned to Wyoming to serve during the Army’s engagement with the Nez Perce – or “Nursey Pursey” as she called them in her memoir. During that campaign she earned her sobriquet, “Calamity Jane”. Her version of the event:

It was during this campaign that I was christened Calamity Jane. It was on Goose Creek, Wyoming, where the town of Sheridan is now located. Capt. Egan was in command of the Post. We were ordered out to quell an uprising of the Indians, and were out for several days, had numerous skirmishes during which six of the soldiers were killed and several severely wounded. When on returning to the Post we were ambushed about a mile and a half from our destination. When fired upon Capt. Egan was shot. I was riding in advance and on hearing the firing turned in my saddle and saw the Captain reeling in his saddle as though about to fall. I turned my horse and galloped back with all haste to his side and got there in time to catch him as he was falling. I lifted him onto my horse in front of me and succeeded in getting him safely to the Fort. Capt. Egan on recovering, laughingly said: “I name you Calamity Jane, the heroine of the plains.”

American Cowboy indicated that the Captain said, “Jane, you’re a wonderful little woman to have around in a time of calamity.” One other version speculates she was given the name by the editor of the Laramie Boomerang – for her presence at various calamities in the form of shootouts and street brawls.

After a brief illness in 1876 while serving with General Crook (who was on his way to join Custer at the Little Bighorn), she headed instead to Fort Laramie where she became acquainted with James Butler “Wild Bill” Hickok. The two of them then traveled together to Deadwood, South Dakota.

Some historians surmise that Jane and Hickok had a romantic relationship. If you go to her entry on the Find-A-Grave web site, someone has created that illusion, linking to his entry as her spouse, as well as them having a child together. However, another friend of Wild Bill’s, “Colorado Charley” Utter, declared that “Wild Bill would have died rather than share a bed with Jane.” She was also rumored to have been a friend of the mysterious and exotic Eleanore Dumont, a.k.a. “Madame Moustache.”

After arriving in Deadwood, she worked as a Pony Express rider between Deadwood and Custer. On August 2, 1876, Hickok was gambling at a saloon when he was shot in the back of the head by Jack McCall. McCall would later claim that he was avenging the killing of his brother in Abilene, Kansas at the hand of Wild Bill. The jury found McCall innocent of the charge of murder. McCall left for Wyoming but just a short time later it was determined that the Deadwood trial had no legal basis since it was located in Indian Territory. He was re-arrested in Laramie on August 29, charged with murder and transported to Yankton, South Dakota to be re-tried. This time he was found guilty and hanged.

Calamity Jane’s version is “somewhat” different:

On the 2nd of August, while setting at a gambling table in the Bell Union saloon, in Deadwood, he was shot in the back of the head by the notorious Jack McCall, a desperado. I was in Deadwood at the time and on hearing of the killing made my way at once to the scene of the shooting and found that my friend had been killed by McCall. I at once started to look for the assassin and found him at Shurdy’s butcher shop and grabbed a meat cleaver and made him throw up his hands; through the excitement on hearing of Bill’s death, having left my weapons on the post of my bed. He was then taken to a log cabin and locked up, well secured as every one thought, but he got away and was afterwards caught at Fagan’s ranch on Horse Creek, on the old Cheyenne road and was then taken to Yankton, Dakota, where he was tried, sentenced and hung.

She remained in Deadwood working the mining camps surrounding the area. When a smallpox plague broke out she helped to nurse people back to health, so she had a tender side. She, however, was still rough around the edges and a brawler who hung out with gunslingers and other disreputable characters.

Another one of her legendary exploits occurred in 1877 while she was riding to Crook City. She came upon a stagecoach that was being pursued by Indians. As she pulled alongside the stagecoach she noticed that the driver was “lying face downwards in the boot of the stage,” having been mortally wounded by the Indians. After the coach pulled up to a station, she took over the reigns of the coach and continued onto Deadwood with the six passengers and the dead driver.

By the mid-to-late 1870’s, Calamity Jane was beginning to make a name for herself, or at least by the legend of her exploits. Her name began to appear in newspapers beginning as early as 1875. Here, though, it’s still difficult to separate fact from fiction. One of the first newspaper accounts I found was in the Chicago Daily Tribune on June 19, 1875, declaring that hers was the same old, old story:

By the mid-to-late 1870’s, Calamity Jane was beginning to make a name for herself, or at least by the legend of her exploits. Her name began to appear in newspapers beginning as early as 1875. Here, though, it’s still difficult to separate fact from fiction. One of the first newspaper accounts I found was in the Chicago Daily Tribune on June 19, 1875, declaring that hers was the same old, old story:

Calamity was a few years ago the respectable proprietress of a millinery store in Omaha. Calamity was good looking, and yielding to drink she soon became a homeless outcast, and as a natural result found herself out on the frontier repenting for a few months, and hiring out to do housework, then being found out, returning to her vicious life, until the next periodical fit of repentance came on.

Nevertheless, she seemed to be, at least in the minds of newspaper readers, whatever the newspaper chose to report, true or not. She apparently roamed all over the West for several years. In 1882 she took up ranching near the Yellowstone River and ran a “way side inn”. She vacated the ranch the following year and went to California, later traveling back to Utah and then back to San Francisco in 1884. In the summer of 1884 she headed to Texas, arriving in El Paso sometime in the fall. There she met Clinton Burke, a native Texan, and the two were married in August 1885. She gave birth to a baby girl on October 28, 1887.

She and her family left Texas in 1889 and moved to Boulder, Colorado where they ran a hotel. In 1893 the Burkes were again on the move, traveling throughout the West: Wyoming, Montana, Idaho, Washington, Oregon and South Dakota. Her notoriety, and her exploits breathlessly reported across the country, must have gained her respect and awe through the years. I found one short obituary in the Council Grove Republican (Kansas) for a young child:

Died in Cowley county – the place of her birth – Calamity Jane, only child of Adversity Greenback and Calamity Howler. The child was only two years old, and died of that dreadful, dire, depressing disease, wind colic.

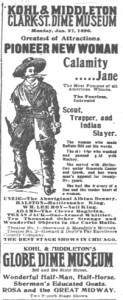

After meeting an agent of the Kohl & Middleton Dime Museum, she came under their management, promoted as the “Greatest of Attractions: Pioneer New Woman”. At some point, I believe she and her husband must have parted ways. American Cowboy reported that the two divorced and her child was raised in a convent. Here too, it is debatable as to what really happened – some accounts claim she was married as many as a dozen times!

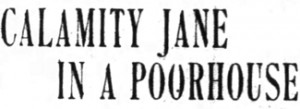

At some point, perhaps as early as 1893, she worked for William “Buffalo Bill” Cody’s Wild West Show as a storyteller and sharpshooter. She was still drinking and carousing freely, however, and was later fired. She found a place to sober up only to return to the bottle and brawling. In early 1901, newspapers were reporting her plight when she was admitted to the Gallatin County (Montana) Poorhouse:

At some point, perhaps as early as 1893, she worked for William “Buffalo Bill” Cody’s Wild West Show as a storyteller and sharpshooter. She was still drinking and carousing freely, however, and was later fired. She found a place to sober up only to return to the bottle and brawling. In early 1901, newspapers were reporting her plight when she was admitted to the Gallatin County (Montana) Poorhouse:

Apparently she found a benefactress, however, who was willing to help. Mrs. Josephine Windfield Brake of Buffalo, New York came to her rescue after finding Jane in “the hut of a negress at Horr, near Livingstone” (Montana). Mrs. Brake, an author and correspondent for a New York newspaper, had heard of Calamity’s plight. Headlines proclaimed that Jane liked the change and would spend the remainder of her days in comfort – except that isn’t how it played out.

Apparently she found a benefactress, however, who was willing to help. Mrs. Josephine Windfield Brake of Buffalo, New York came to her rescue after finding Jane in “the hut of a negress at Horr, near Livingstone” (Montana). Mrs. Brake, an author and correspondent for a New York newspaper, had heard of Calamity’s plight. Headlines proclaimed that Jane liked the change and would spend the remainder of her days in comfort – except that isn’t how it played out.

She made her way back West after her job at the Pan American Exposition (World’s Fair) in Buffalo didn’t work out. She had been working a rather sedate job selling books and receiving a commission. When she became suspicious of her share of the profits, she decided to join the Midway instead. One night she went on a drunken spree and tried to shoot up the whole Midway, which landed her in jail.

By the summer of 1903 she had arrived back in South Dakota. In January of that year she had gone on a rampage, as the Waterloo Press headline proclaimed: “Takes a Freak and ‘Shoots Up’ Town of Sheridan, Wyo.” After arriving in Sheridan she had begun to “load up with liquid enthusiasm.” Next on her agenda was “shooting up the town.” When her ammunition supply was spent, the town marshal put her on a train and sent her on her way. The newspaper noted that although she had been taken in by a Buffalo woman, “the life of an eastern city was too tame for a woman who had fought Indians and ‘plains’ whisky for years.”

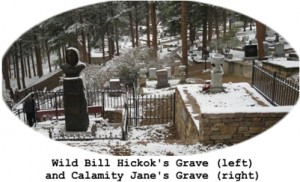

After arriving back in South Dakota, she was taken in by Madam Dora DuFran, proprietor of a brothel in Belle Fourche. There Jane worked as a laundress and cook. In early August she was living in a small room in Terry, near Deadwood, and on August 2, 1903, Calamity Jane died. The Cincinnati Enquirer reported that her last dying request, despite having had twelve husbands, was “that she be allowed to sleep by the side of the man she first loved” – Wild Bill Hickok.

The Enquirer also reported that she had “sent her daughter away for her own good.” Her friends begged her, during her last days, to reveal her daughter’s name but she refused – “Let her be,” she said. The newspaper speculated that the cause of Calamity’s decline and eventual demise was that during her fifty-one years, the “real Wild West was born and died. Its passing left her forlorn.”

The Enquirer also reported that she had “sent her daughter away for her own good.” Her friends begged her, during her last days, to reveal her daughter’s name but she refused – “Let her be,” she said. The newspaper speculated that the cause of Calamity’s decline and eventual demise was that during her fifty-one years, the “real Wild West was born and died. Its passing left her forlorn.”

She may have been a rough-and-tumble character, but the Enquirer reported that through those years she retained two “womanly traits”:

While she might be drunk one day and chasing Indians over the prairie another, she never missed an opportunity to put on skirts and diamonds at a dance. The next morning she would be ready for a trip with the Government mail, or perhaps would be cracking the bottles in a saloon with well aimed bullets. But she would stop abruptly even the incomparable pleasure of “shooting-up” a saloonful of miners bristling with guns, if some one should report a case of sickness. She never refused to go even great distances to nurse the sick back to health.

If one can manage to separate fact from fiction, such was the legend of Martha Jane Canary, a.k.a. “Calamity Jane.”

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Trackbacks/Pingbacks