I ran across an article published in the January 13, 1878 issue of the Chicago Tribune entitled “The Women of the Hills” and written by a correspondent for the St. Paul Pioneer-Press. The correspondent wrote his thoughts on some of the more “colorful” women of the wild and woolly South Dakota Black Hills. He was particularly enamored with Martha Canary, a.k.a. Calamity Jane, calling her “an original in herself” and someone who despised hypocrisy, imitated no one and was “easily melted to tears.”

I ran across an article published in the January 13, 1878 issue of the Chicago Tribune entitled “The Women of the Hills” and written by a correspondent for the St. Paul Pioneer-Press. The correspondent wrote his thoughts on some of the more “colorful” women of the wild and woolly South Dakota Black Hills. He was particularly enamored with Martha Canary, a.k.a. Calamity Jane, calling her “an original in herself” and someone who despised hypocrisy, imitated no one and was “easily melted to tears.”

His list included Belle Siddons, a.k.a. Monte Verde, Kitty LeRoy, known as the queen of just about everything and a young woman known only as Nellie of Central City. His list of colorful characters ended with a paragraph on a “large negro woman, almost as broad as she is long” by the name of “Aunt Sally”.

Sarah Campbell was born on July 10, 1823 in Kentucky to an African American slave named Marianne. It’s possible that the slave owner was Sally’s father because it had been stipulated that Marianne and her children were to be set free upon his death. Marianne instead remained enslaved until her death in 1834.

Sarah Campbell was born on July 10, 1823 in Kentucky to an African American slave named Marianne. It’s possible that the slave owner was Sally’s father because it had been stipulated that Marianne and her children were to be set free upon his death. Marianne instead remained enslaved until her death in 1834.

Six days following her mother’s death, Sally was sold to Henry Choteau, cousin to St. Louis fur trader Pierre Choteau, Jr., who had founded Fort Pierre Choteau in 1832 as a trading post in what would later be called Dakota Territory. Sally, just eleven years old at the time, objected and filed an unlawful detainment lawsuit against Choteau in 1835. With the help of an attorney she won the lawsuit in 1837, and her freedom, and received one penny in damages.

Before her freedom was granted, Sally had been hired out as a cook on steamboats which plied the waters of the upper Missouri River in support of the lucrative fur trade business. After winning her lawsuit, she continued to work on the steamboats and married another steamboat worker from Illinois.

Together they had one son named St. Clair (or Sinclair). Little is known about her life during that time since African American history was sketchy at best during the nineteenth century. St. Clair’s name first appears on the 1870 census at Fort Randall in Dakota Territory where he operated a ferry service until his death in 1885.

According to BlackPast.org, Sally moved to Bismarck, Dakota Territory as a widow. She owned and operated a private club and was a laundress and midwife, affectionately known as “Aunt Sally”. The following year she made history, becoming the first non-native woman to enter the Black Hills when she joined George Custer’s Black Hills Expedition.

Aunt Sally, the expedition’s cook, served over a thousand men. Some have claimed she cooked for Custer, but he had written a letter to his wife and mentioned a cook named Johnson. According to an 1880 Black Hills Daily Times article, she cooked for John Smith, a sutler who sold provisions to the army. She was said to have been handy with a frying pan, not only for cooking purposes, but in fending off anyone who got fresh with her.

During the expedition Sally joined twenty other residents of Bismarck and formed the Custer Park Mining Company. According to True West Magazine, it was the expedition’s intentions all along to not only find a suitable site for a military post to address the Indian problem, but to check out rumors of gold in the Black Hills. After reaching French Creek, two miners began panning for gold and on July 30 found “gold in them thar hills.” Everyone wanted to try their hand, including Aunt Sally.

She called her claim “No. 7 below Discovery”, listed on an official notice posted on August 5, 1874 as belonging to Sarah Campbell. To this day, Custer County still show her claim in their records. One of the soldiers recorded in his diary that “Claim No. 7 below Discovery belonged to ‘Aunt Sally,’ sutler John W. Smith’s Negro cook. Sally’s real name was Sarah Campbell, a woman Curtis [the correspondent] described as a ‘huge mountain of dusky flesh.’”

William Curtis was a young reporter for the Chicago Inter-Ocean and the New York World. His interview with Sally was published on August 27 just before she returned to Fort Lincoln with the expedition, describing her as “the most excited contestant in this chase after fortune. . . She is an old frontiersman, as it were, having been up and down the Missouri ever since its muddy water was broken by a paddle wheel, and having accumulated quite a little property, had settled down in Bismarck to ease and luxury.”

She had anticipated the expedition, saying she “wanted to see dese Black Hills – an’ dey ain’t no blacker dan I am and I’m no African, now you just bet I ain’t; I’m one of your common herd.” One of the things she was known to tell everyone was “I’se the first white woman as ever entered the Hills.” As one correspondent who interviewed her put it, “of course it would be impolite in the presence of a lady to deny the soft impeachment, so I simply accepted the statement as in every sense true.”

Seth Galvin, who as a young boy was acquainted with Sally, claimed she called herself a white woman because “she was not very literate, and the term ‘white’ was the only word she knew. She meant ‘civilized.’” Whether she was literate or not the St. Paul Pioneer-Press correspondent claimed she was a “walking encyclopedia of matters and facts connected with this country.”

After returning from the expedition Sally vowed to return to the hills and continue prospecting, which she did, walking back into the Hills alongside an ox-drawn wagon. She filed a claim at Elk Creek and lived in Crook City and Galena, prospecting, cooking and serving as a midwife. Sally tried her hand at both gold and silver mining, filing a total of five claims, although only one, the Alice Lode silver mine was profitable. Fifteen months before her death she sold the Alice Lode for five hundred dollars.

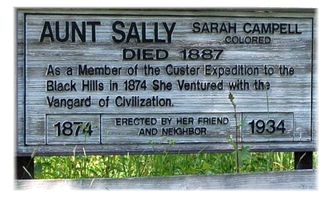

When the silver boom came to an end, she moved to a ranch and adopted a son, planning to run a camp for miners and railroad workers. Aunt Sally died on April 10, 1888 according to her gravestone in Galena’s Vinegar Hill Cemetery, although a grave marker erected in 1934 marking the expedition’s sixtieth anniversary indicated she died in 1887.

She was quite a character, a beloved one at that, who participated in annual parades in her later years and enjoyed telling stories, while puffing on her pipe, about the Custer Expedition. The 1934 marker noted that she with her participation in that expedition she had “ventured with the vanguard of civilization.”

For more information, please see Sarah Campbell: The First White Woman in the Black Hills Was African American, by Lilah Morton Pengra.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

You probably need to mention that this information came from a book copyrighted by Lilah Morton Pengra, Sarah Campbell: The First White Woman in the Black Hills was African American, 2009.