A town’s designation as the county seat often determined whether it would thrive or fade away into history. Some county seat disputes turned into outright wars, bloodshed and all. Others, although politically charged and volatile, were more amicably (or sneakily) resolved. Here are a few of them, some “mild” and some “wild”:

A town’s designation as the county seat often determined whether it would thrive or fade away into history. Some county seat disputes turned into outright wars, bloodshed and all. Others, although politically charged and volatile, were more amicably (or sneakily) resolved. Here are a few of them, some “mild” and some “wild”:

Baldwin County, Alabama

Baldwin County, Alabama was established in December of 1809, named after Senator Abraham Baldwin, a man who actually never set foot in the county. He was a native of Guilford, Connecticut and involved in the founding of the United States Constitution. After graduating from Yale he moved to Georgia to practice law and was later elected to the Georgia State Legislature. Many of the county’s settlers had migrated from Georgia and they suggested the name to honor Baldwin’s accomplishments.

According to the County’s web site, an “undercover scheme” was hatched which would determine the town designated as county seat. The first county seat was a town by the name of McIntosh Bluff, but when it became part of another county, the seat was moved to Daphne in 1868. In 1900 the Alabama Legislature designated a change to make Bay Minette the county seat. The residents of Daphne resisted that move, however.

According to the County’s web site, an “undercover scheme” was hatched which would determine the town designated as county seat. The first county seat was a town by the name of McIntosh Bluff, but when it became part of another county, the seat was moved to Daphne in 1868. In 1900 the Alabama Legislature designated a change to make Bay Minette the county seat. The residents of Daphne resisted that move, however.

Some residents of Bay Minette devised a scheme to draw the sheriff and his deputies out of Daphne by fabricating a murder. While the lawmen were out chasing a phantom criminal, the men who devised the ruse traveled to Daphne, stole the county records and delivered them to Bay Minette. Bay Minette has been the county seat of Baldwin County ever since.

Gray County, Kansas

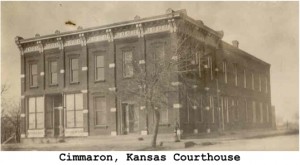

Gray County, Kansas was founded on March 13, 1881 and named after a Kansas politician, Alfred Gray, who had died the year before of tuberculosis. The town of Cimarron, located on the Santa Fe Trail, served as the first county seat. In 1887 three towns vied for the county seat designation: Cimarron, Ingalls and Montezuma.

A few years before, Asa T. Soule had come to the area to invest in a venture proposed by two brothers which would form a vast irrigation system by diverting water from the Arkansas River. Soule was a Rochester, New York millionaire who had made his fortune mostly in the lucrative patent medicine business. Like the majority of medicines peddled as cure-alls in that era, Soule’s Hop Bitters consisted mostly of alcohol.

When Soule came to Kansas he inserted himself into area politics and founded the town of Ingalls. To ensure that Ingalls would be the county seat, he promised to build a railroad from Dodge City to Montezuma which would continue on to the coal fields of Trinidad, Colorado (all free of cost), if only Montezuma would withdraw from the county seat race. When it became apparent that even his promise of a railroad wouldn’t garner him enough county votes Soule tried bribery, dispensing money freely ($100-$500) to residents of Montezuma.

To further advance their schemes, an agent of Soule’s, George Gilbert from Dodge City, came to Cimarron with a group of “enforcers” headed by none other than Bat Masterson. With “long guns and short guns” they camped out at a Cimarron hotel, continuing to dispense monetary bribes to voters on election day October 31, 1887. One witness would later testify that over five thousand dollars was dispensed that day.

Despite those nefarious efforts, however, Cimarron won the county seat race by a forty-one vote majority. According to the Hutchinson News:

The only thing for our citizens to do was to arm ourselves, which they did as well as they could, and protected the polls, preventing the capture of the ballot box, polling lists, etc., and the killing of the election board, for which the gang were to get ten thousand dollars. Nothing but the unfailing courage of our citizens, who had at stake life, property and all that was dear to them, prevented the gang from carrying out the nefarious scheme.

While ballots were being counted, a fire was started, burning down an entire city block of buildings. Cimarron residents suspected the fire was intentional, “set by [their] enemies”. Even though the ballot count favored Cimarron, Ingalls claimed a two hundred vote majority.

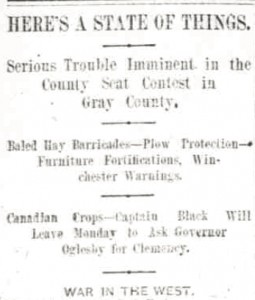

The Wichita Daily Eagle warned of trouble following the election, declaring “War in the West”:

The citizens of Cimarron continued to be harassed by Soule, Gilbert and their cohorts. An attorney, George Dunn, came from Missouri and settled in Cimarron just before the election. In reality he was a “hireling” of Soule and Gilbert. Ingalls placed Dunn on the ballot for county attorney, which he won with the backing of Soule and Gilbert money.

In November, Ingalls challenged the validity of the election, asserting that the election officers who counted the votes would not be officially placed in office until the following January. Dunn, the new county attorney, asked the district court to compel the county officers to move their offices to Ingalls, with which the court agreed. The case became further entangled when the Kansas Supreme Court was called upon to settle the dispute in 1888. However, the Supreme Court declined to rule otherwise and agreed with the district court.

The dispute escalated in early 1889. The county offices, except county clerk and surveyor, had been housed in Ingalls for over a year. When an Ingalls candidate one the election for county clerk, the records were to be moved from Cimarron to Ingalls. On January 12, as deputy sheriffs were loading the records for transfer, a mob of approximately two hundred Cimarron citizens came and began firing upon the deputies. Two were killed and three slightly wounded. The mob captured the county clerk and four of the deputies and held them in the courthouse, until officers from Dodge City came to assist and arranged their release.

The Cimarron vowed revenge, threatening to burn down the town of Ingalls and kill all its citizens. The governor sent the Kansas militia to intervene and by January 14, the newspapers were reporting that Ingalls had been placed under martial law and was quiet.

The Cimarron vowed revenge, threatening to burn down the town of Ingalls and kill all its citizens. The governor sent the Kansas militia to intervene and by January 14, the newspapers were reporting that Ingalls had been placed under martial law and was quiet.

The dispute would go on for quite a while longer, however. The back and forth of politics, heated arguments, bribery, chicanery and mob force resulting in bloodshed, was finally settled a special election held in February of 1893 when Cimarron was finally designated as the permanent county seat of Gray County.

Postscript: The original irrigation scheme which brought A.T. Soule to Kansas turned out to be a bust, becoming known as Soule’s Folly.

Castro County, Texas

The area now known as Castro County, Texas was occupied by Comanches, who had forced out the Apaches in 1720, until the Red River War of 1874 forced them onto reservations. Castro County was established by the Texas Legislature in 1876 and in the early 1880’s the Carters, a ranching family, arrived. Still, by 1890 the county’s population was still miniscule. On March 4, 1890 the Bedford Town and Land Development Company was formed by H.G. Bedford, a resident of Grayson County. On May 27, the company bought a section of land near the county’s center and began to lay out the town, digging a well and building a water tower. One of the partners, Reverend W.C. Dimmitt, was a close friend of Bedford’s and the town was named in his honor.

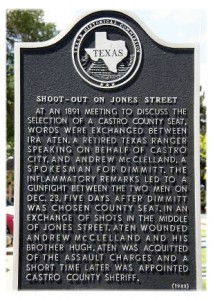

By 1891 the need for local government became more pressing with more settlers coming to the county. Other town sites had sprung up in the county and Castro City and Dimmitt would be the leading candidates for county seat. Two men met on the courthouse lawn in Dimmitt on December 23, 1891. Ira Aten was a retired Texas Ranger representing the interests of Castro City, and Andrew McClelland was a spokesman for Dimmitt.

By 1891 the need for local government became more pressing with more settlers coming to the county. Other town sites had sprung up in the county and Castro City and Dimmitt would be the leading candidates for county seat. Two men met on the courthouse lawn in Dimmitt on December 23, 1891. Ira Aten was a retired Texas Ranger representing the interests of Castro City, and Andrew McClelland was a spokesman for Dimmitt.

Heated remarks led to a gunfight between the two, with Aten wounding Andrew McClelland and his brother Hugh (they recovered). Five days later Dimmitt won the county seat. Aten was later acquitted of assault charges and shortly thereafter was appointed as Castro County Sheriff.

These county seat disputes were mild by comparison to others like the one in Stevens County, Kansas, the bloodiest county seat war in the West, and one in Wichita County (a future Feudin’ and Fightin’ article I’m sure).

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

Good Stuff. Mrs. Hall. I will read your blog often. I don’t post much to my Google + but there are lots of Texas,Arizona,Oklahoma, images and documents.

Thank you so much for your kind words and thanks for stopping by!

sucks you can’ t finish the story without a ad for the history mag.

bait and switch

Sorry, Roger. This blog is in the process of being taken down and converted to a digital format and available by subscription or single issue purchase only. There is no “bait and switch” going on. I am now an accomplished award-winning writer and editor and I want to get paid for my talents. You shouldn’t dismiss the magazine. I can assure you this particular article will make its way to the magazine eventually, enhanced and re-purposed and better than the original. By the way, the magazine isn’t simply a rehash of stories on this site. It’s full of fresh articles every month, running 70-80 pages — no ads to speak of except for the ancestry charts I do. Go to the magazine store and look through the monthly issue. Pick one you’d like to read and I’ll send it to you for free, just to try it out. Here’s the link: https://www.digginghistorymag.com/the-magazine/ Email me at [email protected] with your request.