I normally write Tombstone Tuesday articles about ordinary, everyday people who lived economically and physically challenging lives out on the American frontier somewhere. Today’s article is related to tomorrow’s Ghost Town Wednesday article, and since I ran across his name in my research for that article and found his history fascinating, I decided to write today’s article about Dr. Haller Nutt, a hugely successful businessman in southwest Mississippi and across the river in Louisiana.Haller Nutt was born to Dr. Rushworth “Rush” Nutt and Elizabeth (Kerr) Nutt on February 17, 1816 at the family’s Laurel Hill Plantation in Jefferson County, Mississippi. Haller’s father, Rush, had been educated at the University of Pennsylvania. In 1805, Rush decided to set out on horseback to check out the “Southwest” part of the country. Upon settling in Petit Gulf, Mississippi he set up a medical practice, married and bought a plantation.

I normally write Tombstone Tuesday articles about ordinary, everyday people who lived economically and physically challenging lives out on the American frontier somewhere. Today’s article is related to tomorrow’s Ghost Town Wednesday article, and since I ran across his name in my research for that article and found his history fascinating, I decided to write today’s article about Dr. Haller Nutt, a hugely successful businessman in southwest Mississippi and across the river in Louisiana.Haller Nutt was born to Dr. Rushworth “Rush” Nutt and Elizabeth (Kerr) Nutt on February 17, 1816 at the family’s Laurel Hill Plantation in Jefferson County, Mississippi. Haller’s father, Rush, had been educated at the University of Pennsylvania. In 1805, Rush decided to set out on horseback to check out the “Southwest” part of the country. Upon settling in Petit Gulf, Mississippi he set up a medical practice, married and bought a plantation.

Dr. Nutt began experimenting with developing a better strain of cotton that wouldn’t rot in the field. He traveled to Egypt to observe cotton growing methods and brought back Egyptian seed, crossing it with a Mexican variety. He also tinkered with Eli Whitney’s cotton gin invention by employing the use of steam to drive the machinery. Dr. Nutt, a medical doctor by training, seemed to have a knack for agriculture innovation – encouraging his neighbors to use contour plowing to decrease soil erosion, use field peas as fertilizer and to plow under cotton and corn stalks instead of burning them.

Dr. Nutt began experimenting with developing a better strain of cotton that wouldn’t rot in the field. He traveled to Egypt to observe cotton growing methods and brought back Egyptian seed, crossing it with a Mexican variety. He also tinkered with Eli Whitney’s cotton gin invention by employing the use of steam to drive the machinery. Dr. Nutt, a medical doctor by training, seemed to have a knack for agriculture innovation – encouraging his neighbors to use contour plowing to decrease soil erosion, use field peas as fertilizer and to plow under cotton and corn stalks instead of burning them.

His son, Haller, the subject of today’s article was quite successful himself and shared his father’s talent for agricultural innovation. At the University of Virginia, Haller studied math, chemistry and anatomy-surgery during his first term of 1833-34. During the second term of 1834-35 he studied natural philosophy, chemistry and anatomy-surgery.

When Haller returned home from the University in Virginia, he began to assist his father in plantation operations. In 1840 he married Julia Augusta Williams and they had eleven children. As an ambitious entrepreneur, Haller prospered and over his lifetime owned over twenty separate estates in Louisiana and Mississippi. Before the Civil War his net worth was said to be as much as three million dollars, owning thousands of acres of land and hundreds of slaves.

Some authors have credited the agricultural innovation of Rush Nutt to Haller, but I’ve found sufficient evidence that indicates that those described above are indeed Rush’s accomplishments. Nonetheless, his son was an innovator as well and became fabulously wealthy as a result. KnowLA (Encyclopedia of Louisiana) states that Haller was responsible for improvements in cotton bailing and cotton presses. Haller also compiled a collection of advice tidbits called Book of Receipts, Prescriptions, Useful Rules, etc. for Plantation and Other Purposes. He offered such advice as:

Cockroaches: Mix up fly stone (cobalt) with molasses and place it where they are found.

To kill lice on cattle, hogs, & horses – Wash them with the water in which Irish Potatoes have been boiled.

To measure the contents of a cistern: Square the diameter and multiply by decimals 7854, then by the altitude, then by 1728 & divide by 268-8/10 as in Article No. 4 – and your result is in gallons – or multiply half the diameter by half the circumference and then the altitude as before – or – multiply the whole diameter by the whole circumference, and divide by 1/4 others by altitude & 1728 & divide by 268-8/10.

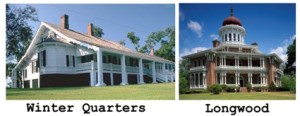

Two of Haller Nutt’s most notable properties were Winter Quarters and Longwood. The original Winter Quarters property had been purchased by his wife’s grandfather, Job Routh, in 1805. In 1850 Haller purchased the property and made several improvements. In the spring of 1860 construction began on Longwood, an opulent six-story, thirty thousand square feet mansion. He engaged the services of a Philadelphia architect and by the beginning of the Civil War the exterior had been largely completed. According to this web site, Haller’s slaves were tasked with the job of making over 750,000 bricks to be used in the construction of Longwood. But when the war broke out the northern builders and carpenters abandoned the construction site and headed back home. By 1862, nine rooms had been completed by using slave labor.

Rush’s and Haller’s various innovations through the years had helped boost the cotton industry in the deep South, which quite likely encouraged the use of increasingly more slave labor. Here, however, is where I found a curious fact about Haller Nutt. He was a Union sympathizer… in the deep, deep South, himself owning hundreds of slaves.

Rush’s and Haller’s various innovations through the years had helped boost the cotton industry in the deep South, which quite likely encouraged the use of increasingly more slave labor. Here, however, is where I found a curious fact about Haller Nutt. He was a Union sympathizer… in the deep, deep South, himself owning hundreds of slaves.

In this personal handwritten letter, he encourages Alonzo Snyder to run for election as a delegate to the secession convention:

Haller believed that secession would occur but hoped that it would be forestalled as long as possible, praying for reunion with the rest of the country except the New England states.

Even with construction halted on his Longwood estate, Haller was determined to press on despite the war and volatile political climate, but eventually he was forced to abandon the project until hostilities ceased. When Sherman began his march through the South, Haller and his family relocated to Natchez, Mississippi, leaving Winter Quarters in the hands of a caretaker. General Grant had ordered the destruction of everything not needed by the Union troops. Before Sherman’s March there were fifteen plantations lining the banks of St. Joseph Lake and when the smoke cleared, Winter Quarters was the only one still standing. The caretaker had been able to secure letters of protection from two of Sherman’s advance officers, General McPherson and General Smith.

Winter Quarters’ salvation notwithstanding, Haller Nutt suffered devastating financial losses during the War which led to foreclosure proceedings on his Louisiana plantations. On June 15, 1864, at the age of 48, Haller Nutt died of pneumonia. Some have suggested he died of a broken heart. His family was later successful in petitioning the federal government to compensate them for at least some of the damages incurred.

Winter Quarters was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1978. Longwood is owned and operated by Pilgrimage Garden Club as an historic museum.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

I’ve read about Longwood before because it’s octagonal. When I was a caretaker / docent at an octagon house, I did a lot of research on octagonal structures.

Cool .. which house did you work at?

Really Epic! From the way where did you get that picture?