She was born under less than “normal” circumstances. Her birth mother had fallen in love with someone who promised to marry her upon his return from a trip to Kentucky. When his trip was extended, she despaired and thought that she had been betrayed. She settled for a “drunken, worthless vagabond” who was overseer of a neighboring plantation. But then her true love returned, and upon finding her married, promptly left for France. Some time later, her birth mother and her first love had an extramarital affair which resulted in Elsa’s birth. Elsa, however, was turned over to her mother’s brother to raise.

She was born under less than “normal” circumstances. Her birth mother had fallen in love with someone who promised to marry her upon his return from a trip to Kentucky. When his trip was extended, she despaired and thought that she had been betrayed. She settled for a “drunken, worthless vagabond” who was overseer of a neighboring plantation. But then her true love returned, and upon finding her married, promptly left for France. Some time later, her birth mother and her first love had an extramarital affair which resulted in Elsa’s birth. Elsa, however, was turned over to her mother’s brother to raise.

Elsa remembered that as a young girl she was adored by both her uncle and his negro servants, and often her mother, “Aunt Anna”, would visit. At the age of five, Elsa was sent to New Orleans to attend school, and only saw her uncle on occasion – they communicated mostly through letters and he always made sure she was well provided for.

At the age of twelve, something changed because Elsa, according to her autobiography, “developed with a rapidity marvelous even in the hotbed, the South, and upon reaching the age of twelve, I was as much a woman in form, stature and appearance as most women at sixteen.” She met a man who she thought handsome and they began to meet on the sly, since he was not allowed to visit her at the school. He won her heart and one morning she packed everything she could carry and made her escape through a window. Not long after she was, in her words, “standing before a clergyman and was united for better or worse, to him to whom I had given the first fruits of my affections.”

She soon learned that her new husband was a steamboat pilot on the Mississippi – something she had not thought to inquire about before her marriage. They had a pleasant honeymoon traveling through the South and after a month they settled in St. Louis. She settled into her new life as a wife, happy and content and not the least bit regretful of her decision. In her words, “My happiness was, if possible, made greater when at the end of about a year after my marriage, I found a breathing likness [sic] of my husband laid by my side. Three years after my marriage, another stranger came among us – this time a daughter.”

She soon learned that her new husband was a steamboat pilot on the Mississippi – something she had not thought to inquire about before her marriage. They had a pleasant honeymoon traveling through the South and after a month they settled in St. Louis. She settled into her new life as a wife, happy and content and not the least bit regretful of her decision. In her words, “My happiness was, if possible, made greater when at the end of about a year after my marriage, I found a breathing likness [sic] of my husband laid by my side. Three years after my marriage, another stranger came among us – this time a daughter.”

Life was good — what more could a woman ask for than a loving husband and two beautiful children. Tragedy struck, however, just three months after the birth of her daughter. One day while playing with her son a knock was heard at the door – the news was not good. Her husband had been shot, mortally wounded, by a fellow shipmate named Jamieson who was settling a grudge.

Still reeling from shock and grief, a few days later she received a letter informing her of Anna’s death. Anna’s last letter to Elsa was also enclosed and in it “she revealed to me the sad secret of my birth, but told it such loving words that it took away the sting of its illegitimacy.” Two blows in a short time, but one more shock was coming. She was soon informed by her attorney that her husband had spent money as he had earned it, never setting aside any for the future. Elsa was financially crippled, “completely a beggar”, in her words.

By this time, Elsa was probably only sixteen years old and faced with a seemingly insurmountable situation. She did not allow it to get her down, but instead began to develop a bitter hatred for the person who had made her a widow and a beggar – Jamieson! The more desperate her financial situation became the more hate she felt for the man. She searched for a way to get retribution for Jamieson’s crime against her husband and was eventually forced into pawning her possessions and taking a life-altering and drastic step.

She being so young had never learned any sort of trade and knew that her gender and age would be held against her, preventing her from supporting herself and her children. So, she determined to do something “so religiously closed against my sex” – she began to dress herself in male attire. She also thought it would give her better chance to carry out her desire to some day get revenge for her husband’s death.

Jamieson had been tried and convicted but had managed to escape punishment because of a legal technicality. She approached a friend of her late husband and asked for his help. Although he was reluctant to be involved in her plans to disguise herself as a male, he eventually relented when she convinced him it was her only means to avoid starvation. He purchased her a suit of boy’s clothes.

To put her plan into operation, Elsa turned her children over to the Sisters of Charity. She cut her hair to the normal length of a man’s, donned the suit and “endeavored by constant practice to accustom myself to its peculiarities and to feel perfectly at home.” She looked like a boy of fifteen or sixteen years old and a previous asthmatic condition which left her with a bit of hoarseness in her voice was a perfect way to complete her disguise. Elsa became Charley.

After several fruitless attempts to find employment, Charley finally found a job as a cabin boy on a steamer that ran between St. Louis and New Orleans. She would earn $35 per month, determined to endure a life as the “stronger sex”. Luckily, her job was menial in nature so that she could quietly attend to her work without drawing attention to herself. Once a month she would visit her children, first stopping at the friend’s house to change into a dress. It was difficult, but she remained on the boat for almost a year before she found another job as second pantryman. She changed jobs about every six months for a period of time. After she left her last river boat job, she became a brakeman for the Illinois Central Railroad in the spring of 1854.

She was still supporting her children and knew that if she reverted back to life as a woman she would never be able to support them in the manner she had become accustomed to in the four years since donning male attire. But then again, she liked the freedom that the male disguise gave her – she could go anywhere she chose – and “the change from the cumbersome, unhealthy attire of woman” was more suited to her.

While working for the railroad, her boss became suspicious of her gender and plotted to trick her into revealing her true identity. She overheard the plot and was able to escape, this time heading to Detroit. After a tour that took her to Niagra Falls and Canada she decided to return to St. Louis with and eye to eventually head to St. Joseph and westward. While in St. Louis she visited her children, but also ventured out in male attire to walk the streets of the city. One day she overheard a name – Jamieson. As she turned to look she contemplated whether to pull the trigger on the concealed revolver she carried. But then she thought really there was no need to hurry – he wasn’t going anywhere and if she acted it “would end the sweet anticipations of revenge which filled my soul.”

So she followed him to a gambling hall and watched him for hours. When he finally departed, Charley caught up to him and revealed her true identity to him. She pulled out her revolver and shot at Jamieson who immediately drew his gun and fired at her – neither was harmed. Jamieson fired again and Charley was hit in her thigh – she fired again and shot Jamieson in his left arm. The whole scene had lasted about five seconds and both managed to escape, although Charley passed out in an alley.

Upon awakening she found herself in a clinic, attended by a physician and an elderly woman. Her thigh was broken and required six months to completely heal. The elderly woman cared for Charley and her children came to visit. But when her recovery was complete she found her finances depleted and resumed her disguise. Gold fever had still not subsided and Charley joined a party of sixty men headed to California. Leaving her children was difficult, but she saw no other means to provide for them.

She made the long and arduous journey, keeping a journal as the group made their way across the vast prairies and mountains between Missouri and California. Upon reaching her destination, she found the job of gold miner unsuitable and instead found a job in a Sacramento saloon which paid $100 per month. She later invested and became part owner of the saloon, followed by a successful business in the speculation of buying pack mules. She later left her business in the care of someone else, deciding she was homesick to see her children.

She stayed in St. Louis for awhile, but two years after she made her first trip to California she started another one. The trip, however, did not go well. The party included fifteen men, twenty mules and horses and her cattle. When they reached alkali waters she lost 110 cattle, unable to prevent them from drinking the poison. Further down the trail, near the Humboldt River, they were attacked by Snake Indians. The party was forced to fight them off, Charley doing her part by shooting one Indian and stabbing another. One of the men was killed and Charley was severely wounded in her arm.

Upon reaching the Shasta Valley, Charley bought a small ranch to feed her stock until she could sell them. She returned to Sacramento to check on the business she had left behind, finding that it had done quite well. When she sold the business, her stock and the ranch, she had a tidy sum of $30,000 to send on to St. Louis. St. Louis, however, was not as exciting as the life Charley had found out west. She joined the American Fur Company and headed west again.

Charley returned to St. Louis for a time before heading out once again for Pike’s Peak and another gold rush – but not finding much gold for her efforts. She moved to a location closer to Denver and still not having much success, decided to open a bakery and saloon. After contracting mountain fever, she was forced to move to Denver. She rented a saloon and called it the “Mountain Boys Saloon” and kept it through the winter. By the spring of 1859 she was again restless, and deciding to try gold prospecting again she made $200 by the end of the summer. Returning to Denver she bought back her saloon, but soon events would take a disastrous turn for someone and her long-held secret would be revealed. In the spring of 1860, Charley was riding about three miles out of Denver and encountered someone she knew – Jamieson!

He recognized me at the same moment, and his hand went after his revolver almost that instant mine did. I was a second too quick for him, for my shot tumbled him from his mule just as his ball whistled harmlessly by my head. Although dismounted, he was not prostrate and I fired at him again and brought him to the ground. I emptied my revolver upon him as he lay, and should have done the same with its mate had not two hunters at that moment come upon the ground and prevented any further consummation of my designs.

Jamieson was not dead, however. The hunters made a litter to carry him back to Denver. Jamieson had severe wounds, although not fatal. He recovered and journeyed to New Orleans only to die of yellow fever soon after his arrival.

Charley’s identity had been revealed by Jamieson and he explained to the authorities the circumstances, relieving Charley of any blame for the attempts she had made on his life. Her story soon made the headlines – Horace Greeley wrote from Pike’s Peak to the New York Tribune about her story.

Charley continued dressing in male attire and during the winter of 1859-60 operated her saloon. She soon fell in love and married her bartender, H.L. Guerin. In the spring of 1860 they sold the saloon and moved to the mountains to open a boarding house and mine. That fall they returned to Missouri to be reunited with her children, which is where her memoir ended.

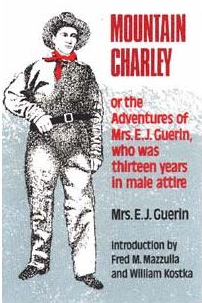

Quoted material in this article are excerpts from Charley’s memoir, Mountain Charley, or the Adventures of Mrs. E.J. Guerin, Who Was Thirteen Years in Male Attire. It’s an interesting read – especially the chapter (which I didn’t elaborate on) of her first trek to California. The book is a free download here and only 52 pages.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!

the best website in the history of time

thank you for making this website

I am thankful for many thing things but this is what I am most thankful for

Thanks for stopping by to read the blog!

cool