Here’s an excerpt from a “Mining Genealogical Gold” article in a Digging History Magazine issue featuring Colorado. The article in its entirety was originally published in the May-June 2019 issue and entitled, “Crazy in Colorado: Wheels in Their Head and (Other) Insane Stories:

I came across some unique records several years ago while conducting research for a client. She wanted me to focus on an ancestor with a tragic story – she died at the Colorado State Insane Asylum in Pueblo in 1927. This institution has a long and storied history.

A series of small gold strikes precipitated the so-called Pike’s Peak Gold Rush as “Fifty-Niners” – Pike’s Peak or Bust! – flooded the region for three years before the rivers and streams played out. In 1879 silver was discovered high in the mountains at Leadville, founded in 1877 and known as “Cloud City” at an elevation well over 10,000 feet. On February 8, 1879 the Colorado State Legislature enacted legislation to establish the young state’s first public hospital for the insane.

At any given time during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries there were plenty of people deemed insane in Colorado. Many were confined to the state asylum in Pueblo, and if the asylum was full, in local jails. Local authorities, no doubt, preferred to shuffle their crazies off to the state facility in Pueblo.

Early asylum records indicate quite a few Leadville residents ended up in Pueblo for one reason or another. Was it the altitude? Was there something in the water (or the whiskey)? Was it the isolation of the miner toiling day in and day out, hoping for the next big strike, only to come up empty-handed again (and again)?

“Wheels in Their Heads”

That was the Rocky Mountain News headline on September 8, 1893 as one man after another was adjudged insane in a Denver court. Alfred B. Clark, standing trial for lunacy, appeared fully sensible as most – until someone brought up the subjects of electricity and religion. “Then he became wild.”

Another, John Gunnison, had been accused of killing another man and was now in constant fear of someone attempting to murder him. Albert Anderson’s “bump of locality” (a phrenological term) had been injured, so much so he believed himself to be somewhere near the Columbian exposition (being held in Chicago that year). Another had received a bump on his noggin and insane ever since.

Overcrowding at the Pueblo asylum was a constant problem. The same could be said for county hospitals often forced to take in the insane. In November 1896 the Rocky Mountain News was decrying the level of care for the county’s “wheely citizens”. After all, the county hospital had never been intended to house this unfortunate group of citizens numbering around thirty.

One reporter “took in the whole works” courtesy of a member of the medical staff. The insane population ranged from the “white-haired old lady who is simply ‘off’ at times, to the wild, destructive maniac in whose diseased brain is moulded only by a desire to kick, bite, glare and make a ‘large noise.’” The second floor was home to a “miscellaneous assortment of the daft, all women.” None were really much trouble at all, but someone had to keep an eye on them at all times.

In 1894 the county hospital had its hands full with one unfortunate inmate, Harry Noble Fairchild, a former Colorado Assistant Secretary of State. Again, the state facility was full. Fairchild put on quite a display at his hearing, as the room was filled with leading politicians of the city and state:

He was brought from the county hospital in charge of guards, his hands in muffs and his wild cries startling all who were in the building. So violent was the form of the mania that he was not permitted to take the stand, and it was with greatest difficulty that he was restrained from doing injury to the spectators. “Harry Noble Fairchild!” he screamed, “The first god of the earth.” . . . Amid the turmoil created by his cries, the people sat quietly, and no remark of the insane man, although many were witty and some grotesque, caused a smile on the face of anyone. . . In maudlin tones Fairchild fought again the battles of the war, which he entered as a boy. . . Again he was behind the walls of Andersonville, and lived over the days and months of anguish, hunger and cruelty [his name doesn’t appear in Andersonville prison records]. . . He never ceased speaking for an instant, and most of his remarks were addressed to the court. “Judge! Judge!” he yelled, addressing the court, “both your legs are off, and your heart’s been hanging out for some time.” Airships, canary birds, campaigns and other things and objects were hopelessly tangled in his brain. . . The doctors testified that the disorder was, under certain conditions, curable. The jurors saw the strange actions of the man, and these were far more convincing than the testimony of experts. They were absent only a few moments, and amid a hush Clerk Reitler read the verdict, that “Harry Noble Fairchild is so disordered in his mind as to be dangerous to himself and to others, and as to render him incapable of managing his own affairs.”

What became of Harry Fairchild is unknown. Perhaps he died in Pueblo. In 1992 skeletal remains of approximately 130 people were uncovered near the site of the original grounds, leading anthropologists to posit them buried there between 1879 and 1899. Inmates would have likely been buried in unmarked graves.

I first encountered this database while researching for a client who wanted to know more about her great-grandmother who had been committed to the Pueblo asylum in the early 1900s. Her condition appeared to have been related to uncontrolled epileptic seizures, once thought to have been caused by evil spirits.

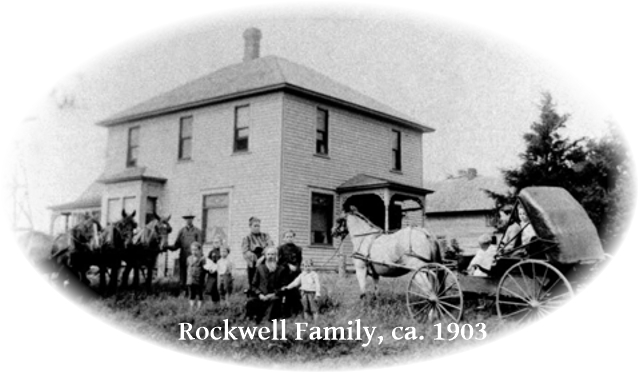

Martha Lorena Rockwell married German immigrant Folkert (Frank) Bokelman in 1908 in Cass County, Nebraska. Lorena was the daughter of Abraham and Mary Ann Rockwell, one of their ten children, growing up on a farm near Weeping Water, Nebraska (Cass County). Lorena was 17 and Frank was 28. Six children later, Lorena filed for divorce in April of 1920. Sometime in 1920, records indicate Lorena also spent time in the Lincoln State Hospital.

Presumably, the divorce petition was dropped at some point because by 1922 Lorena had been committed to the Woodcroft Hospital in Pueblo, Colorado. According to the Wray Rattler, Wray County (Colorado) was footing the bill for her board and care.

Frank had moved his family to Sidney, Nebraska (although likely lived in Yuma, Colorado at some point it appears) and on June 18, 1922 signed papers committing Lorena to Woodcroft. She was also pregnant with yet another child. Colorado State Hospital notes indicate Lorena was admitted from Woodcroft on November 6, 1922 in the last stages of pregnancy. Her baby was born in Ward 4 soon afterwards.

On June 18, 1923 Frank arrived to take Lorena and the baby home to Sidney. He signed a release form, “contrary to the advice of the Superintendent”. Should his wife require more care she would be placed in a Nebraska facility. Although it’s unclear as to why Lorena went to the Colorado facility in the first place (being a native Nebraskan), she returned to Pueblo on August 24, 1923 because the Nebraska institute refused to care for her. Frank brought her home to Sidney and she ran away. Clearly, he could not care for her.

Even though Lorena was committed once again to the Pueblo hospital was she really insane? That may not have been the case, at least in the clinical sense. Hospital records point to her history of grand mal seizures. Newspaper accounts also bear out those facts, although not implicitly stated.

On February 21, 1914 the Omaha Daily Bee reported the following:

Mrs. Frank Bokelman was seriously scalded Tuesday. She fell while carrying a teakettle filled with hot water. The hot water scalded her body from the neck down.1

Three years later The Plattsmouth Journal reported another accident:

Mrs. Frank Bokelman was badly burned on the left arm and right hand Monday morning when she fell on the cook stove while preparing the morning meal.2

How frequent were the seizures? While in the Colorado State Hospital it was noted Lorena was well-oriented, clear and a good worker between seizures. Otherwise, when the seizures were active, she might seize three or four times a day (grand mal), followed by a respite of one or two weeks. Through the years her pregnancies appear to have increased the frequency and severity of the seizures. No wonder she was seeking a divorce!

Lorena Bokelman died on June 18, 1927 of tuberculosis with the contributing condition of “psychosis with epilepsy”. By this time her children had been placed in other homes, adopted by strangers. Shortly after Lorena’s death, Frank died as well, although exactly where or how is unclear. While researching Lorena and Frank Bokelman for a client and looking for records of the Pueblo hospital, I came across this somewhat obscure asylum database.

While I didn’t find anything specifically about Lorena Bokelman in the asylum database, glancing through this voluminous set of records revealed some fascinating information which would help me understand more about people who, like Lorena, had no other medical recourse than to be committed to an asylum. This particular database didn’t contain hospital records, but snippets compiled from census records and newspapers. Not surprisingly, the newspaper clippings provided the most enlightening information (yet another reason why newspaper research is essential to genealogy!). For more information regarding this unique database (link provided in the magazine article), see the link in the opening paragraph to purchase this issue.

Thanks for stopping by! For more stories like this one, consider subscribing to Digging History Magazine. Purchasing a subscription entitles you to subscriber benefits (20% off all services, including custom-designed family history charts) AND a chance to win your very own custom-designed family history chart! Details here (or click the ad below).

Thanks for stopping by! For more stories like this one, consider subscribing to Digging History Magazine. Purchasing a subscription entitles you to subscriber benefits (20% off all services, including custom-designed family history charts) AND a chance to win your very own custom-designed family history chart! Details here (or click the ad below).

Thanks for stopping by! For more stories like this one, consider subscribing to Digging History Magazine. Purchasing a subscription entitles you to subscriber benefits (20% off all services, including custom-designed family history charts) AND a chance to win your very own custom-designed family history chart! Details here (or click the ad below).

Footnotes: