Here’s a look back at a 2019 article published in Digging History Magazine, a personal one, from an issue which featured the War of 1812:

I hadn’t looked at this particular line for some time, but after someone saw this particular surname on my family’s pedigree chart (with an interesting story of someone with the same surname) I decided to take another look. I suspect I set it aside some time ago because, at least circumstantially, it appeared I had the correct parents for my third great grandmother Mary Ann Connelly, yet I couldn’t locate absolute proof.

So, a little more digging was in order. Curiously, I had several hints for Mary Ann’s mother but not her father, Henry Connelly. After realizing I had mistakenly input an incorrect birth location — dang auto-correct(!) — I registered several hints for him. After clicking on the new hints I found previously posted bits and pieces of War of 1812 Pension and Bounty Land Warrant application files. These were actually part of an extensive package (41 pages) of what turned out to be a “Eureka!” moment for researching this family line.

Henry and Sarah (Phillips) Connelly married on August 20, 1810 in Clay County, Kentucky, this according to affidavit after affidavit from Sarah Connelly following passage of the War of 1812 Act of February 14, 1871. In part:

The act of February 14, 1871, granted pensions to survivors of the war of 1812, who served not less than sixty days, and to their widows who were married prior to the treaty of peace.1

Sarah began her quest not long after the bill’s passage, engaging the services of attorney William F. Terhume in April.

Henry, born circa 1787, enlisted in the Kentucky militia on November 10, 1814 and was honorably discharged on May 10, 1815. Among the qualifications for a widow’s pension was to prove you and your now-deceased spouse had married and co-habitated prior to the Battle of New Orleans (January 8, 1815).

In 1871 Sarah was eighty years old, and while she would eventually have problems remembering the company Henry had served with and a few other details, she remembered the date of her marriage and the ceremony performed by Reverend Spencer Adams, a Baptist preacher. Clay County was established in December 1806, carved from parts of Madison, Floyd and Knox counties. Whether her marriage in the early days of Clay County contributed to her inability to locate proof is unclear, as Sarah discovered there was no official or public record of the marriage. The marriage had been witnessed by four long-deceased individuals, and Henry had passed away in 1859 (dropsy according to the 1860 Mortality Schedule).

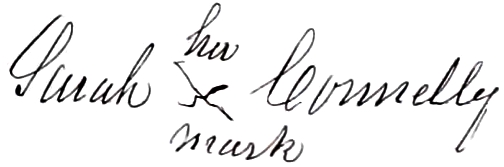

Mr. Terhume began the process after an agreement for payment of services to be rendered ($25.00) was executed on April 5, 1871. By her mark Sarah agreed to those conditions:

Terhume wrote the first letter six days later, addressed to the Commissioner of Pensions:

Terhume wrote the first letter six days later, addressed to the Commissioner of Pensions:

I enclose a pension claim under the late act of Congress for a widow of a soldier who served in the war of 1812.

I trust you will find it in sufficient form. Permit me to suggest that these claims should receive early attention for the reason that the applicants are quite aged and may not live many of them to enjoy the bounty of the government.2

Terhume also inquired about instructions, and if any existed, requested copies. Ever so promptly (not!) the government sent a circular dated September 16, 1871. In the following order the government required proof:

● A certified copy of a church or other public record.

● An affidavit of the officiating clergyman or magistrate.

● The testimony of two or more eyewitnesses of the ceremony.

● The testimony of two or more witnesses who know the parties to have lived together as husband and wife from the date of their alleged marriage, the witnesses stating the period during which they knew them thus to cohabit.

● Before any of the lower classes of evidence can be accepted, it must be shown by competent testimony that none higher can be obtained.3

As previously noted the first three forms of proof were out of the question — three strikes, Sarah is out?

Included in the first correspondence, executed on the same day as the fee agreement, was an extensive affidavit witnessed and averred to by Sarah’s son-in-law William H. Pugh (my third great grandfather) and his brother George Washington Pugh who had married a woman also surnamed Connelly (she also being a Mary, and Mary Ann’s cousin I believe).

In this affidavit significant information was provided as evidence Henry Connelly had served during the War of 1812. Included with information provided was a proclamation of total allegiance to the United States. Given that the Civil War was still a touchy subject, perhaps Mr. Terhume thought it best to include this statement:

… and further that at no time during the late Rebellion against the authority of the United States did I [Sarah] adhere to the enemies of the United States government neither gave them aid or comfort, and I solemnly swear to support the Constitution of the United States.4

It was also noted that Sarah had already received a land warrant from the government. (Eventually the government would indeed produce its own evidence, a Widow’s Claim for Bounty Land originally authorized on August 31, 1864.)

Her son-in-law and his brother signed similar statements, both pledging fealty to the federal government. Based on the government’s September 1871 response the original statements had been insufficient to move forward with Sarah’s claim. The matter was “suspended” in January 1872 until proof of cohabitation could be provided.

Meanwhile, Terhume had been pursuing, with diligence, means of proof, yet without success. He continued to try and locate someone in Kentucky who would remember, but by September 25, 1872 had received no response. Terhume had found someone willing to keep digging in Kentucky but would likely have no further proof until at least January of 1873.

Sarah was in a bind as far as the matter of marriage proof was concerned. So, what to do when you’re in a pinch? Call on your in-laws, of course!

It’s a bit curious to me the family didn’t think of this before, but on January 13, 1873 an affidavit was signed by two of Sarah’s in-laws. One was Mary Pugh, George’s wife and the other was Frances Pugh, my other fourth great-grandmother. I like to call her “Feisty Frances”.

Frances Townsend Pugh was born in Virginia on June 26, 1794. A few months before her sixteenth birthday she married William Pugh. Their marriage produced twenty-one children, thirteen of whom lived to adulthood. William (born in 1787) died in 1869 and Frances, according to Vernon County, Wisconsin history, was “well preserved and enjoyed good health.”5

At the age of ninety she was still able to take walks and one day came upon a rattlesnake with seven rattles. The snake slithered away but Frances grabbed a stick, “hunted the venomous reptile out from his hiding place and killed it; this took more courage than most of her children and grandchildren would have possessed.”6

Frances was certain Henry and Sarah had been married prior to the Battle of New Orleans because she recalled the birth of one of her own children the same year and day of the month as a child Sarah had delivered. While Mary Pugh (George’s wife) agreed about the marriage, Frances’ statement was the strongest.

Their statements helped settle the matter it appears, because on January 23, 1873 the government issued a “Brief of Claim for a Widow’s Pension” for Sarah Connelly. The brief referenced a report from the Bounty Land Division, along with previous statements by George and William Pugh and Frances and Mary Pugh.

Sarah Phillips Connelly was granted a widow’s pension of eight dollars per month. Sarah died on September 6, 1874 at the age of eighty-three. I found Sarah’s story compelling, as told through the back and forth correspondence, wrangling with the federal government. Obviously, her memory was failing as she struggled to remember certain facts, at one time stating Henry was a Private and Express Rider, and in another statement he was a Lieutenant (big difference!). I also felt her pain. Why is that?

I felt her pain and more than likely her frustration. It made me think of what we as genealogists go through to find the ABSOLUTE proof required to prove so-and-so is our ancestor. In regards to the absolute proof I had been looking for, one of the documents listed William and Sarah’s children — Mary Ann among them. She lived in an age where there was no such thing as “instant” anything in terms of vital information. Sarah, her attorney and her family persisted, however, until they were successful. And, so must we all. As I always like to say — KEEP DIGGING!

Thanks for stopping by! For more stories like this one, consider subscribing to Digging History Magazine. Purchasing a subscription entitles you to subscriber benefits (20% off all services, including custom-designed family history charts) AND a chance to win your very own custom-designed family history chart! Details here (or click the ad below).

Thanks for stopping by! For more stories like this one, consider subscribing to Digging History Magazine. Purchasing a subscription entitles you to subscriber benefits (20% off all services, including custom-designed family history charts) AND a chance to win your very own custom-designed family history chart! Details here (or click the ad below).

Footnotes:

- Executive Documents Printed by Order of the House of Representatives 1875-76, Washington

Government Printing Office, 372. - War of 1812 Pension Files, accessed October 17, 2019 at www.fold3.com.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- History of Vernon County, Wisconsin (Springfield, Illinois: Union Publishing Company, 1884), 605.

- Ibid.