From time to time I run across an unfamiliar term while researching family history. Having a natural curiosity, I feel compelled to learn more about it — and sometimes that turns into quite a research foray all its own. Such was the case of discovering what the term “grass widow” meant. It turned out to be quite the research adventure! From an extensive article published in the September-October 2021 issue of Digging History Magazine, here is an excerpt:

As genealogists we have all come across terms which are unfamiliar for one reason or another. Many times the word or terminology is obsolete, or it might mean something altogether different in the twenty-first century.

As genealogists we have all come across terms which are unfamiliar for one reason or another. Many times the word or terminology is obsolete, or it might mean something altogether different in the twenty-first century.

Grass Widow

I don’t remember exactly the circumstances of how or when I came across the term “grass widow”. It was certainly a curious term and I was not at all acquainted with what the term meant. A little research was in order, especially after I found references to the term in both newspapers and census records. As is often the case there are stories to be told, but first a definition is in order.

The term “grass widow”, according to Merriam-Webster, was first used circa 1699. In terms of usage, Merriam-Webster provides a two-tiered definition, suggesting the term dates back to the late 17th century. In those days “grass-widow” meant either “a discarded mistress” or “a woman who has had an illegitimate child.” Thereafter, the term may still have implied some sort disreputable behavior, but it also came to mean “a woman whose husband is temporarily away from her” or “a woman divorced or separated from her husband”.1 Any of those definitions could be construed as untoward in one way or another.

However, the Oxford English Dictionary suggests the term dates back to the 16th century. Either way, the earliest definition of “grass widow” carried a certain disreputable stigma. In a Grammarphobia blog article, entitled “Grass widow or grace widow?”, the writers attempt to determine whether there is a distinction between “grace widow” and “grass widow”. The Oxford English Dictionary suggests “grass widow” is a corruption of “grace widow”, although it does not in fact provide a definition for “grace widow”. It is a rather muddled argument either way.

Perhaps the distinction was best defined, as cited in the blog article, by a letter to the editor in an 1859 issue of Ladies Repository, a Methodist magazine:

GRASS-WIDOW – The epithet is probably a corruption of the French word grace – pronounced gras. The expression is thus equivalent to femme veuve de grace, foemina vidua ex gratia, a widow, not in fact but – called so – by grace or favor. Hence, grass-widow would mean a grace widow: one who is made so, not by the death of her husband, but by the kindness of her neighbors, who are placed to regard the desertion of her husband as equivalent to his death.2

Later versions of the Oxford English Dictionary suggested that “words for grass and straw ‘may have been used with opposition to bed.’ So a “grass widow” might provide a roll in the hay, so to speak – an illicit sexual tryst, not necessarily in a bed.”3 However, the blog authors suggested that by the mid-nineteenth century the term “grass widow” had become less derogatory and generally meant a woman’s husband was away. If you’re researching family history and you come across the term, perhaps in a census record, you will need to determine what “away” really meant. Was the husband working elsewhere? Had he run off and left his family to fend for themselves (or ran off with another woman)? Was he perhaps away at war, or had there been a divorce?

I recently came across an indirect reference to “grass widow” while reading The Taking of Jemima Boone, by Matthew Pearl. The book covers the kidnapping of Daniel Boone’s daughter, Jemima, as well as quite a ride through early Kentucky history. According to Pearl, with Daniel away for long stretches, her birth carried a certain question mark:

For the Boone family, Daniel’s long absence evoked many earlier stretches away from home, both planned and unplanned, including one that, according to community lore occurred almost sixteen years before. That time, months had stretched into nearly a year before Daniel reappeared after a “long hunt.” Memories and anecdotes about the timing of that absence plagued the family thereafter. By the time Daniel reappeared – so variations of the story went – Rebecca had conceived a child, gone through a pregnancy and given birth to their fourth child, Jemima. . . .

Rumors posited that the long-absent Daniel could not have been little “Mima’s” father, and that her biological father, to compound matters, was really one of Daniel’s brothers, Squire or Ned. By one account, when told the truth by a remorseful Rebecca, Daniel shrugged and commented that his child “will be a Boone anyhow.” Some remembered Daniel laughing over the years about the rumor, in the process tacitly admitting to it. In some versions, Rebecca felt light embarrassment over the topic – sitting knitting with her “needles fly[ing]” when it came up in conversation with visitors – while in other accounts, Rebecca ribs Daniel that if he’d been home, he could have avoided the problem.4

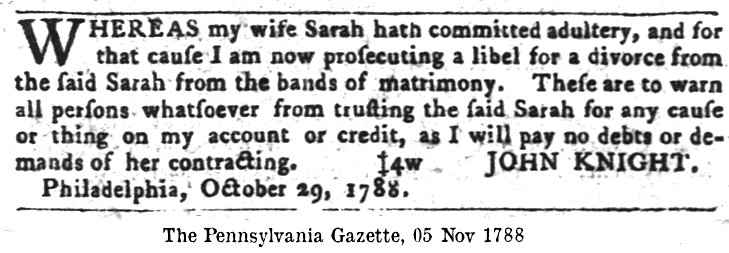

Was Rebecca Boone a “grass widow”? Perhaps, but Daniel always came home – eventually. Still, in the eighteenth century men could divorce their wives for adultery.

Whether it was the husband divorcing the wife or vice versa, breaking the “bands of matrimony” was stigmatized, and in the 18th century not necessarily an easy thing to obtain. Some have suggested a grass widow was a divorcee and perhaps it was kinder for her community to refer to her as a grass widow. . . .

For more discussion (and anecdotal evidence) on this topic (including the husbands who contracted “gold fever” in the mid-1800s) and to read the rest of this extensive article, purchase the issue here.

![]() Thanks for stopping by! For more stories like this one, consider subscribing to Digging History Magazine. Purchasing a subscription entitles you to subscriber benefits (20% off all services, including custom-designed family history charts) AND a chance to win your very own custom-designed family history chart! Details here (or click the ad below).

Thanks for stopping by! For more stories like this one, consider subscribing to Digging History Magazine. Purchasing a subscription entitles you to subscriber benefits (20% off all services, including custom-designed family history charts) AND a chance to win your very own custom-designed family history chart! Details here (or click the ad below).

Footnotes:

- Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, s.v. “grass widow,” accessed November 5, 2021, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/grass%20widow.

- Patricia T. O’Conner and Stewart Kellerman, “Grass widow or grace widow?”, accessed on November 5, 2021 at https://www.grammarphobia.com/blog/2016/11/grass-widow.html.

- Ibid.

- Matthew Pearl, The Taking of Jemima Boone (New York: Harper-Collins, 2021), Ebook loc. 1939.