As the world has rapidly changed in the past few days I couldn’t help but remember another pandemic. Whether the one we’re dealing with now will turn out to be as devastating (I seriously doubt it and certainly hope and pray not!) remains to be seen. With modern technology — both in terms of medical and mass communication — historians will likely record a different account for our current crisis versus the one which faced the world in 1918. Interestingly, however, the 1918 pandemic also had a suspected Chinese connection. History does have a way of repeating itself, doesn’t it?

As the world has rapidly changed in the past few days I couldn’t help but remember another pandemic. Whether the one we’re dealing with now will turn out to be as devastating (I seriously doubt it and certainly hope and pray not!) remains to be seen. With modern technology — both in terms of medical and mass communication — historians will likely record a different account for our current crisis versus the one which faced the world in 1918. Interestingly, however, the 1918 pandemic also had a suspected Chinese connection. History does have a way of repeating itself, doesn’t it?

The November 2018 issue of Digging History Magazine was dedicated to articles focused on World War I — the Spanish-Flu, finding records from World War I, and more. This issue is on sale at a reduced price of $2.99 (half-off the normal price of $5.99 per single issue). In the meantime, here’s the article from this issue, entitled “Pandemic! On the Home Front: Blue as Huckleberries and Spitting Blood”:

SPRING 1918: War headlines were intense enough by the spring of 1918 – the world was reeling from a war unlike any other in the history of the world. Soon – very soon – the world would be reeling from a different kind of war.

SPRING 1918: War headlines were intense enough by the spring of 1918 – the world was reeling from a war unlike any other in the history of the world. Soon – very soon – the world would be reeling from a different kind of war.

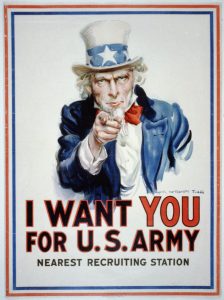

War costs were mounting. The United States government was propagating propaganda at a frenetic pace. Liberty Bonds. Victory Gardens. Our Boys Need SOX Knit Your Bit. Uncle Sam Wants You.

As a result, Americans were increasingly caught up in the war effort and, as it turned out, would soon unknowingly begin propagating an insidious virus known as “Spanish Flu” or “Spanish Lady” across the country. As the virulent strain made its way around the world in three successive waves it would prove to be more deadly than The Black Death – or The Great War itself.

Even today, one hundred years later, no one is certain beyond all doubt the source of the virulent strain known as Spanish Flu. Years of research, exhuming bodies of victims, extracting organ and tissue samples and debating the various theories have revealed at least three possible flash points, however.

At first the most obvious answer seemed to be the abysmal trenches of France – soldiers in close quarters, the stress of war, cold and damp weather all magnified the potential for rapidly spreading disease.

In March 1918 forty-eight soldiers died at Camp Funston (Kansas). Medical officers were certain the outbreak of influenza, which they feared would lead to the spread of pneumonia, was caused by dust storms in the area.

300 FUNSTON MEN DEVELOP INFLUENZA AFTER DUST STORM1

Despite spreading oil around the camp to keep dust from blowing around, soldiers were still falling victim to influenza. Many had also been given anti-typhoid serum. At one night’s retreat several soldiers had suddenly fallen unconscious, yet doctors didn’t believe it was anything too serious. Today some surmise the pandemic may have begun in the American Midwest, spreading from birds and farm animals and eventually infecting humans.

Following years of extensive research one well-regarded Canadian historian, Mark Osborne Humphries, strongly believes the more likely ground zero location of Spanish Flu actually occurred in November 1917 in a northern Chinese province near the Great Wall of China. The evidence seemed more certain after Humphries found archival evidence indicating Chinese scientists identified their country’s 1917 strain as being identical to the one which would become widely known as Spanish Flu, although it may have been a less virulent strain in the beginning.

While hundreds were affected it appears at some point as the initial strain spread globally it mutated into the more virulent strain responsible for millions of deaths worldwide by the time it had run its lethal course. As serious as the situation was poised to become, much like Camp Funston medical officers, most didn’t seem too concerned that they were seeing anything but the normal “garden variety” of influenza which came around every year like clockwork. For months newspapers overflowed with advertisements for remedies to either ward off or cure any number of maladies, including influenza.

Another reason why Humphries strongly suspects the China connection is the fact Chinese Labor Corps workers (about 25,000) were sent across Canada in route to Europe about the time of the outbreak in their own country. The French and British, desperate to free their soldiers for frontline duty, ordered the Chinese workers sent to southern England and France.

The workers were carried across Canada in sealed railroad cars, and by the time they reached camps where they would await deployment to England and France, about 3,000 were quarantined. The reason they had been transported in sealed cars was due to anti-Chinese sentiments. Doctors who treated the quarantined workers gave them castor oil for their sore throats, attributing their illness to the stereotypically “lazy nature” of Chinese race.2

After the workers arrived in France hundreds would die as a result of respiratory illness. Interestingly, however, the Chinese laborers who continued to work in France for the duration of the war (and especially during the height of the pandemic in the autumn of 1918), appeared to have been immune as no additional outbreaks of respiratory illness occurred among their ranks. Apparently, the milder strain had immunized them against the more virulent one, much like today’s yearly flu shots are designed to work.

Given this possible explanation for the source (China), why is it still referred to as “Spanish Flu”? That’s a good question since Spain has never been considered one of the possible ground zero locations. The term most likely came into wide use after King Alfonso XIII of Spain, along with many of his fellow Spaniards, fell victim to the influenza which had mutated by the spring of 1918 into the more virulent strain.

It wasn’t, however, that Spain was particularly hard hit. Other countries were seeing mounting numbers of cases. Yet, if one looks today at newspaper archives from that time period you will note how little was mentioned about the potential seriousness or the possibility of a widespread epidemic. British and American doctors speculated in medical journals since newspapers at the time were not permitted to print stories that might engender widespread panic.

Spain, however, was a neutral nation during World War I and the Spanish press had no such restrictions. The term “Spanish Influenza” or “Spanish Flu” was in wide use by June 1918, yet ridiculed by The Times of London in a pithy column:

THE SPANISH INFLUENZA

A SUFFERER’S SYMPTOMS

Everybody thinks of it as the “Spanish” influenza to-day. The man in the street, having been taught by that plagosus orbilius, war, to take a keener interest in foreign affairs, discussed the news of the epidemic which spread with such surprising rapidity through Spain a few weeks ago, and cheerfully anticipated its arrival here. He is sometimes inclined to believe it is really a form of pro-German influence – the “unseen hand” is popularly supposed to be carrying test-tubes containing cultures of all the bacilli known to science, and many as yet unknown. In 1889-10, however, it was the “Russian” influenza, because in those far-off days Russia was a land of melodramatic mysteries for most of us, and therefore, the likeliest birthplace of a swift and strange disease, “the ghost of the Plague,” as it was imaginatively defined.3

Yes, The Times opined, the illness came on suddenly and unexpectedly, “the change from what seemed comfortable good health to feverish incompetence being achieved melodramatically”, but a hot water bottle, bed rest and quinine would seem the best cure. Europe, after all, had historically seen far worse epidemics.

The following month a Dutch newspaper opined that Germany’s severe outbreak (resulting in numerous deaths daily) was actually caused by hunger. The German potato ration has been severely curtailed, and thus undernourishment was surely the cause.4

In mid-August New Yorkers were pooh-poohing the notion of a potential epidemic as well:

Spanish influenza is said to be here, but some doctors call it merely mild pneumonia. These cynics seem to think Spain has never originated anything, not even a disease, since Don Quixote.5

That week a Dutch steamship arrived in New York carrying “a large number of passengers suffering from so-called “Spanish” influenza and a record of five third-class passengers buried at sea”.6 Health officials issued cautions, but were not particularly alarmed (yet):

IF YOU MUST KISS, KISS VIA KERCHIEF, IS WARNING: Otherwise You May Get Spanish Influenza, or It Will Get You, Board of Health Tells the Amorously Inclined

Further self-denial was urged upon New Yorkers yesterday as a result of the possibility that Spanish influenza may make its appearance here. Dr. Royal S. Copeland, Commissioner of Health, officially advised again kissing, “except through a handkerchief.” Although perhaps distasteful to some devotees of the sport, it was explained in this connection that the precaution would be found both simple and effective as a means of evading disease.

It is the view of the Health Department authorities that the “handkerchief kiss” – there is no objection to the most diaphanous of silk – should be brought into vogue at once, despite the fact that all the suspected cases of Spanish influenza thus far under observation have turned out to be simple, old fashioned article. . . “There is nothing to be alarmed about so far as I can see,” Dr. Copeland declared.7

Alarming or not, the worst – the deadly second wave – was yet to come.

The situation between mid-August to mid-September was fluid. Cases in New York were reportedly mild and Health Commissioner Copeland was officially discounting the possibility of an epidemic. That was Friday, September 13. Two days later a large outbreak was reported at Camp Deven in Brockton, Massachusetts – two thousand cases.

By Tuesday, September 17 Copeland had declared influenza and pneumonia as reportable diseases, although he still did not want to call it the Spanish Influenza which was hitting Boston and other areas of the country. An epidemic was drawing closer, however, as Camp Upton on Long Island was closed the same day. At Camp Upton the situation was fluid as well, reporting one day influenza was under control and the next more closures.

Even as deaths began to be reported Copeland cautioned against hasty diagnosis. However, by the end of September a rash of cases had manifested – almost 700 in a 48-hour period. One family in Flatbush was stricken and the mother had just died.

Meanwhile, the situation in Massachusetts was out of control. Lieutenant Governor Calvin Coolidge appealed to Woodrow Wilson and governors of nearby states to respond via telegram:

Massachusetts urgently in need of additional doctors and nurses to check growing epidemic of influenza. Our doctors and nurses are being thoroughly mobilized and worked to the limit. Many cases can receive no attention whatever. Hospitals are full, but arrangements can be made for outside facilities. Earnestly solicit your influence in obtaining for us this needed assistance in any way you can.8

Meanwhile, Commissioner Copeland was sure what New York was dealing with wasn’t Spanish influenza, but rather “a peculiar form of pneumonia of an epidemic type.”9 Again, however, he saw nothing alarming even though the number of cases were beginning to tick upwards. The man was either clueless, overly cautious or an extraordinary optimist.

By the last day of September a hospital train sent from Baltimore was headed to Boston, equipped with forty beds to care for influenza victims. The number of cases had risen, alarmingly so, to possibly as many as 85,000. The city of Quincy was particularly hard hit.

Finally, on the first day of October (and as it turned out, October would the deadliest month across the nation), Copeland admitted “there was an increase in the number of Spanish influenza cases” – 836 in a 24-hour period, “reaching epidemic proportions. However, he said, that so far there was no reason to be alarmed, as all means were being taken to safeguard the public.”10

In the first few days of October the number of cases continued to climb in New York City, Boston and Philadelphia. Philadelphia schools were closed, the Hog Island Shipyard was impacted and young doctors were urged to come to the City of Brotherly Love. Public gatherings were prohibited, including churches and saloons.

The New York City Health Department had their inspectors out in force, policing railway stations. On October 4, 135 men were summoned to court – “charged with spitting on public thoroughfares.” The court magistrate fined them each $1 and told them to be careful and aid authorities who were trying to keep the epidemic from getting out of control.

“It is cheaper and cleaner to use a handkerchief”, said Magistrate Groehl in the Washington Heights Court this morning, as he fined nine delinquents $5 each and one $10, with the alternative of one day, for spitting in the subway. One of the aggressors was an east-side doctor and another a subway guard.11

In Quincy, Massachusetts officials had discovered milk may have been spreading the disease. Health officials found filthy conditions in cow barns and cows being milked by people seriously ill with influenza. In some places where the milk was strained in kitchen sinks, sick children were laying around on mattresses.12

It was becoming clearer this sickness wasn’t the garden-variety influenza everyone hoped it would be. Reports began showing up in newspapers regarding victims stricken one day and a day (or less) later they had died. Keeping track of deaths and where to house the bodies until enough coffins could be located – these were the serious issues facing city government, health officials and undertakers.

Camp Upton was overwhelmed with a mounting number of cases among young soldiers. For some inexplicable reason this particular strain of influenza was most dangerous to the young and heretofore healthy. One woman, mother of eleven children, had received word one day that her son was stricken at Camp Upton. The following day a telegram arrived announcing his death. However, when she opened the coffin, the body was not that of her son.

In Pennsylvania, Philadelphia had been overwhelmed as were many other ports along the eastern seaboard. Officials had been dealing with the epidemic for several days as it spread across the state, hopeful it would soon begin waning. That was Page 1 of the Evening Public Ledger (Philadelphia) on October 9. Page 2, however, told a different story.

INFLUENZA KILLS THREE OF FAMILY

DOCTOR AND NURSE DIE

The father, mother and daughter of one family had all died and were scheduled to be buried in the same grave. This would be the case for scores of victims as cemeteries were filling up.

A doctor and nurse at St. Joseph’s hospital had died trying to save others.

A woman died within twenty-four hours after the husband she had cared for passed away.

PRISONERS DIG GRAVES

Undertakers and grave diggers were overwhelmed, unable to keep up with the demand. Prisoners from the Camden, New Jersey jail were brought in to “help relieve funeral stress.”

Hospitals were filled to capacity, opening new wards and still they came.

Twelve female employees of the Victor Talking Machine Company were being temporarily assigned to train and work as hospital volunteers.

INFLUENZA GAINS IN STATE: Believe Crest of Epidemic Has Not Yet Been Reached

While Philadelphia cases may have been waning, areas like Lancaster and Harrisburg were still experiencing new cases and more deaths.

Several short death notices were published on page 2 – all had died of influenza.13

On October 5 The Philadelphia Inquirer published a one-page warning in bold lettering – a crisis had arrived. The epidemic was imperiling the success of the Fourth Liberty Loan. Elaborate parades had been the vehicle for rallying the public to support the war effort (by funding it, actually, via Liberty Bond). These parades were no doubt the brainchild of Wilson’s chief propagandist, George Creel. On September 28 Philadelphia hosted a parade for the Fourth Liberty Loan as crowds lined both sides of Broad Street.

Thousands of parade-goers were infected and bodies began piling up – literally. The city morgue only held 36 bodies, yet within a few days hundreds of bodies had arrived. Five hundred bodies were placed in five private mortuaries (without embalming or refrigeration), yet by the end of October when the epidemic was all but over in the city, only about two hundred had been buried thus far. Despite a citywide quarantine, almost 12,000 had died, the hardest-hit city in the United States.14

One Philadelphia mortuary run by the Donohue family had been in business for twenty years and had always maintained meticulous funeral and burial records. Earlier that year records were neat and orderly, listing funeral details, where the deceased was buried and so on. The family later noted:

But when you got to October 1918, the ledgers became sloppy and confused; things are crossed out, scribbled in borders. Information is scant and all out of chronological order – it’s nearly impossible to keep track of what’s going on, it’s just page and page of tragedy and turmoil. Sometimes we got paid. Sometimes we didn’t. Usually, we buried people we knew. Other times, we buried strangers. One entry reads: ‘A girl.’ Another says ‘A Polish woman.’ Another ‘A Polish man and his baby.’ Someone must have asked us to take care of these people and it was just the decent thing to do. We had a responsibility to make sure things were done in a proper, moral, dignified manner. Scribbled at the bottom of the ledger, below the entry for the ‘girl,’ is ‘This girl was buried in the trench.’ This girl was one addition to the trench. I guess we had nowhere else to put her.15

New York City was experiencing much the same with hospitals at capacity. At Bellvue in Manhattan victims were dying in beds, in corridors, on stretchers lining the hallways. Children were placed three to a bed. Housekeeping employees had fled in fear; clean linens were in short supply.

Doctors and nurses had no scheduled rounds, instead rotating in and out twenty-four hours a day. Patients were arriving in unprecedented numbers, all with the same disturbing symptoms – and not just the typical aches and pains accompanied by fever, but “torrential nosebleeds, explosive hemorrhaging, air-hunger and cyanosis.” No wonder one doctor at Columbia Presbyterian Hospital in Washington Heights was heard to remark, “They’re blue as huckleberries and spitting blood.”16

As the epidemic spread westward to cities like Chicago, Detroit and Cleveland and pushing back into the Midwest, conditions eased up along the eastern seaboard. Conditions were bad enough, although not as devastating as had been experienced in Boston, New York and Philadelphia. Still, bodies piled up as coffins, undertakers and grave diggers were in short supply.

In Indianapolis an emergency order was issued by the War Industries Board:

FANCY COFFINS RESTRICTED TO SPEED PRODUCTION

It was an unusual demand, yet with bodies accumulating at alarming rates, coffin manufacturers were being asked to “make only the simpler forms of coffins at present.”17

Public health officials across the country were banning public funerals in an effort to keep the epidemic from spreading. It didn’t matter whether the person had died from influenza or some other cause. In Arkansas undertakers who chose to defy the ban would be prosecuted. In early December, after much of the second wave had passed, Salt Lake City was still banning public funerals although the epidemic had peaked in early November.

Apocalyptic scenes from a different source had occurred in Minnesota on October 10-12 when fire swept through the northern part of the state, destroying entire towns. The area had already been impacted by the epidemic and worsened when refugees were housed in emergency shelters. Even if allowed to hold a public funeral the bodies had been burned beyond recognition. One newspaper referred to it as a “holocaust”. It is still the worst natural disaster in Minnesota with 450 deaths.

One of the more enduring images of the pandemic was the one depicted on the cover this month’s issue – the face mask. In truth the mask provided very little protection since the virus could easily pass through the thin, gauzy fabric, yet many cities passed emergency ordinances compelling their citizenry to don a face mask or face a fine.

While most San Franciscans followed the city’s face mask directive, several were charged with disturbing the peace and fined $5.00 – or jail time. On October 28 a deputy health officer shot a man for his refusal to don a mask. In the City-by-the-Bay, fashion mattered as some women wore veils, hanging loose below the chin and not such a “disturbing and flattening effect upon certain types of female beauty as has the mask that is tied under the mouth close to the chin.” The San Francisco Chronicle called the use of these innovative masks “wonderful attempts to blend the arts of beauty and prophylaxis”.18

Still, forcing the public to don masks in order to stem the spread of epidemic influenza had its drawbacks for at least one San Franciscan. On the evening of October 28, taxi cab driver W.S. Tickner was attacked, beaten and robbed by three “masked” men.

In El Paso, Texas a makeshift hospital was opened at a school. R. J. Pritchard of the El Paso Times provided a stark description – which no doubt was repeated thousands and thousands of times around the world – of poor Mexican immigrants in the last stages of pneumonia:

Fifty-one Mexican men, women and babies lay gasping in the improvised wards of the emergency hospital at Aoy school last night. Brought in from the squalor of homes in the Mexican quarter of town, many of them in the last stages of pneumonia, all of them suffering from lack of proper medical attention and comforts, the patients were transferred to the comparative comfort and care of a hospital equal in almost every respect to any in the city. . . Mexicans of every age, and in every stage of the disease, lay tossing on canvas army cots in the throes of acute pneumonia, or else lay still, with faces upturned to the ceiling, eyes glassy, and only their heaving chests and whistling breath betraying the extent of their agony.

Here lay a grizzled Mexican, tossing from side to side, his body in constant motion as he groaned perpetually for breath. Beside him on the next cot lay a small babe, hardly more than two months old, its brown hands clenched on the coverlet and its tiny black head motionless upon the pillow . . .

On one cot a young mother, not more than 18 years old, sat upright, clasping in her arms with a convulsive grip a three months’ old child. Careless of her own exposure, which might mean her death, the maternal spirit dominated her being to the exclusion of all else, as she fondled her cough-racked babe.19

Spanish influenza was certainly no respecter of persons. While a great number of those succumbing to the disease were poor immigrants, it was just as likely to strike those who were well-to-do or famous. In California actress Lillian Gish had a brush with death. In Chicago a teenager who went by the nickname “Diz” had convinced his parents to allow him to train as an ambulance driver. After he became ill he was sent home to recover. He later became the world’s most famous animator, better known as Walt Disney.

Earlier in the year a wealthy immigrant entrepreneur who had made his fortune during the Yukon gold rush, operating restaurants and boarding houses (some say brothels). On May 29, 1918 he was out walking with his son in New York City when he was suddenly stricken ill. Frederick Trump, grandfather of Donald Trump, died the following day as one of the early victims of the 1918 pandemic.

According to The History Channel web site, as many as 675,000 Americans died as a result of influenza. As staggering and devastating a number as that would seem to be, the worldwide toll may have been as high as 50 million.20 At the time an effective means of vaccinating the populace at large against these kinds of outbreaks had yet to be developed as scientists were still learning about how disease spread in the first place, and how to effectively treat bacterial and viral infections.

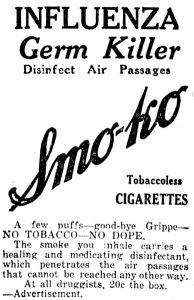

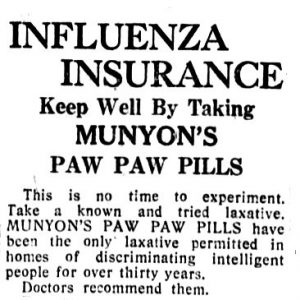

Wearing a mask or turning to folk remedies and patent medicines was, of course, wholly inadequate, but medical science was simply not advanced enough to address the overwhelming impact of the pandemic. Still, purveyors of patent medicines (“quack medicine” being a more accurate term) made a fortune selling their “miracle cures” to a fearful and too-often gullible populace.

Wearing a mask or turning to folk remedies and patent medicines was, of course, wholly inadequate, but medical science was simply not advanced enough to address the overwhelming impact of the pandemic. Still, purveyors of patent medicines (“quack medicine” being a more accurate term) made a fortune selling their “miracle cures” to a fearful and too-often gullible populace.

While one Philadelphia laboratory was selling “Influenza Insurance” in the form of their “Paw Paw Pills”, and druggists were selling “Smo-ko” tobaccoless cigarettes (for 20 cents a box), the life insurance industry was selling product as well. One Brooklyn agency was offering double indemnity for Spanish influenza. By the end of the pandemic several million dollars would be paid out in claims. The federal government claimed it would eventually pay out a whopping $170 million to settle the claims of soldiers who had died of influenza.

For some Spanish influenza pushed them to the brink of insanity, enough to either attempt to or succeed in taking their own life. While today it is a well-known fact that influenza and pneumonia can lead to delirium, it may not have been understood in 1918. In Brooklyn, a 29 year-old Austrian man had been ill for several days. After pneumonia developed, the stage when many victims turned blue (cyanotic), he became delirious and leapt out a third story window before his brother could stop him. He died after being impaled on an iron picket fence.21

The commander of Camp Grant, near Rockford, Illinois, was so distraught over the number of recent deaths (500) that he shot himself in the head.22 In mid-November a Hanover, Pennsylvania man slashed his throat in an attempted suicide carried out on the front steps of a Russian church.23 In Suffolk, England a man, who along with his entire family, was suffering from influenza killed his family and then himself in the most gruesome way – a neighbor found the man’s body hanging in the bedroom and “the bodies of the other three persons, whose heads were smashed with a chopper and who were stabbed with a bayonet.”24 Spanish influenza was a horrible disease which drove more than a few completely over the edge.

America already had a tuberculosis crisis before the pandemic as an estimated one million Americans were afflicted. In early December reports were coming in from Spain and England which pointed to an alarming increase in tubercular patients following a bout of influenza. American doctors warned people to be aware of the possibilities and to take the necessary precautions, including avoiding the urge to self-diagnose. The Surgeon General also advised against the use of remedies sold by “unscrupulous patent medicine fakers.”25

America already had a tuberculosis crisis before the pandemic as an estimated one million Americans were afflicted. In early December reports were coming in from Spain and England which pointed to an alarming increase in tubercular patients following a bout of influenza. American doctors warned people to be aware of the possibilities and to take the necessary precautions, including avoiding the urge to self-diagnose. The Surgeon General also advised against the use of remedies sold by “unscrupulous patent medicine fakers.”25

After cessation of hostilities U.S. soldiers began returning home and may have precipitated the pandemic’s third wave during the winter and spring of 1919. During the first few days of January several hundred more cases were reported in San Francisco and over one hundred deaths. New York City feared another severe outbreak when over seven hundred cases were reported resulting in 67 deaths.

The disease was still rampant overseas, Paris in particular, as world leaders gathered at the Versailles Peace Conference in April to officially negotiate the war’s end. Historians debate whether Woodrow Wilson collapsed at the conference as a victim of influenza or was suffering debilitation stemming from a history of strokes.

The 1918-1919 Spanish Influenza Pandemic was a world-wide disaster, the likes of which the world had never seen before nor since (thankfully). It would take another twenty years before the first flu virus was successfully developed by Jonas Salk and Thomas Francis in 1938.

The vaccine came none too soon as another world-wide war was looming. United States soldiers received vaccinations and, unlike their World War I counterparts, were better protected against influenza.

This is an example of the insightful articles you’ll find in every issue of Digging History Magazine. As you can see, the articles I write now are significantly longer and more detailed than previous blog articles. This is why a digital publication (PDF) works better. It’s more work (WAY more), thus the reason why I ask for payment. Single issue purchase is available here, Subscriptions are the best deal — choose from one-year, semi-annual and quarterly or try our new “trial subscription” with a no-obligation-to-renew price.

This is an example of the insightful articles you’ll find in every issue of Digging History Magazine. As you can see, the articles I write now are significantly longer and more detailed than previous blog articles. This is why a digital publication (PDF) works better. It’s more work (WAY more), thus the reason why I ask for payment. Single issue purchase is available here, Subscriptions are the best deal — choose from one-year, semi-annual and quarterly or try our new “trial subscription” with a no-obligation-to-renew price.

Footnotes:

- The St. Louis Star and Times, March 14, 1918, accessed at www.newspapers.com on November 4, 2018, 4.

- Dan Vergano, National Geographic, “1918 Flu Pandemic That Killed 50 Million Originated in China, Historians Say”, accessed on November 4, 2018, at https://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2014/01/140123-spanish-flu-1918-china-origins-pandemic-science-health/.

- The Times (London), June 25, 1918, accessed at www.newspapers.com on November 4, 2018, 23.

- The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, July 13, 1918, accessed at www.newspapers.com on November 4, 2018, 1.

- The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, August 15, 1918, accessed at www.newspapers.com on November 4, 2018, 6.

- The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, August 18, 1918, accessed at www.newspapers.com on November 4, 2018, 47.

- The Sun (New York), August 17, 1917, accessed at www.genealogybank.com on November 4, 2018, 13.

- The New York Times, September 27, 1918, accessed at www.newspapers.com on November 4, 2018, 6.

- Ibid.

- The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, October 1, 1918, accessed at www.newspapers.com on November 4, 2018, 16.

- The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, October 4, 1918, accessed at www.newspapers.com on November 4, 2018, 11.

- The Boston Globe, October 4, 1918, accessed at www.newspapers.com on November 5, 2018, 5.

- Evening Public Ledger (Philadelphia), October 9, 1918, accessed at www.newspapers.com on November 5, 2018, 2.

- The Philadelphia Inquirer, October 25, 1918, accessed at www.newspapers.com on November 5, 2018, 7.

- Catherine Arnold, Pandemic 1918: Eyewitness Accounts from the Greatest Medical Holocaust in Modern History (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2018 [ebook]), Loc 1992-2000.

- Arnold, Loc 1782.

- The Indianapolis Star, October 20, 1918, accessed at www.newspapers.com on November 4, 2018, 11.

- San Francisco Chronicle, October 25, 1918, accessed at www.newspapers.com on November 6, 2018, 9.

- El Paso Times, October 19, 1918, accessed at www.newspapers.com on November 7, 2018, 7.

- Spanish Flu, History Channel, accessed on November 6, 2018 at https://www.history.com/topics/world-war-i/1918-flu-pandemic.

- The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, October 16, 1918, accessed at www.newspapers.com on October 12, 2018, 3.

- Star-Gazette (Elmira, New York), October 8, 1918, accessed at www.newspapers.com on November 7, 2018, 2.

- The Wilkes-Barre Record, November 19, 1918, accessed at www.newspapers.com on November 7, 2018, 17.

- The Times (London, England), November 6, 1918, accessed at www.newspapers.com on November 7, 2018, 3.

- Moundridge Journal (Moundridge, Kansas), December 5, 1918, accessed at www.newpapers.com on November 7, 2018, 4.