This area of Texas is home to just a handful of residents these days, but once boasted a population of four thousand. The town was named for Colonel (later General) William R. Shafter, commander at Fort Davis, and located about eighteen miles north of Presidio. It became a mining town after rancher John W. Spencer found silver ore there in September 1880.

This area of Texas is home to just a handful of residents these days, but once boasted a population of four thousand. The town was named for Colonel (later General) William R. Shafter, commander at Fort Davis, and located about eighteen miles north of Presidio. It became a mining town after rancher John W. Spencer found silver ore there in September 1880.

Shafter had the sample assayed and found it contained enough silver to make it profitable to mine – profitable enough for Shafter himself to invest. Spencer had thought it prudent to share his secret with Shafter since the area was prone to periodic Indian attacks. Protection would be needed to carry out successful mining operations.

Shafter called upon two of his military associates, Lieutenants John L. Bullis and Louis Wilhelmi to join his venture (and clear the area of unfriendlies). The following month Shafter and his partners asked the state of Texas to sell them nine sections of school land in the Chinati Mountains. Eventually only four sections were purchased, but lacking capital the partners leased part of their acreage to a California mining group. Shafter later obtained financial backing in San Francisco and the Presidio Mining Company was organized in the summer of 1883.

Shafter called upon two of his military associates, Lieutenants John L. Bullis and Louis Wilhelmi to join his venture (and clear the area of unfriendlies). The following month Shafter and his partners asked the state of Texas to sell them nine sections of school land in the Chinati Mountains. Eventually only four sections were purchased, but lacking capital the partners leased part of their acreage to a California mining group. Shafter later obtained financial backing in San Francisco and the Presidio Mining Company was organized in the summer of 1883.

The company contracted with Shafter, Wilhelmi and Spencer individually to purchase their interests, each receiving five thousand shares of stock and $1,600 cash. Bullis had purchased two sections in his wife’s name, but when the company’s manager William Noyes found deposits on the Bullis acreage (valued at $45 per ton), a dispute arose. Bullis claimed the two sections had been purchased outright by his wife with inherited funds and not part of the partnership. An injunction was filed to halt mining in that section until the spring of 1884 when operations resumed.

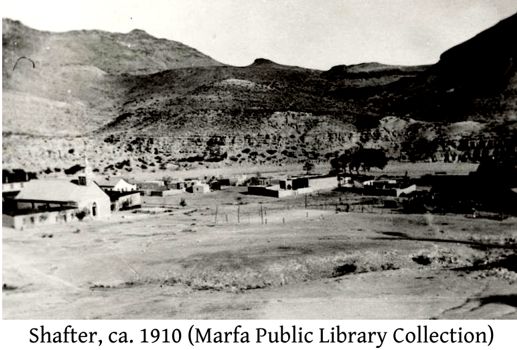

The town of Shafter, situated on Cibolo Creek at the east end of the Chinati Mountains, grew up around the mining operations and a post office was established in 1885, this despite the fact supplies and other resources were hard to come by given its remote location. After legal wrangling over the Bullis sections was concluded, Noyes hired around three hundred men.

Mexicans from both sides of the border, as well as African-Americans, were hired and paid well, and until the Alaska gold rush in 1897 California miners also worked the Presidio Mine. Just like mining towns across the West, miners lived in company housing, shopped at the company store and were treated by the company doctor.

By the turn of the century the town’s population was growing with two saloons, a dance hall, church and a school. A wood-cutting firm was contracted to provide fuel for the furnaces, but by 1910 the wood was exhausted and oil from Marfa was trucked in. Silver pockets were found at around seven hundred feet, some yielding as much as five hundred dollars per ton of ore. By 1913 mules had been replaced by a tram to haul the ore out.

Not long after the town was founded, Texas Rangers were called upon to handle sporadic violence. Then came 1914 – the Mexican Revolution and Pancho Villa – and cause for increased vigilance. Although the mine closed and reopened several times in the 1920’s and 1930’s and the Presidio Mining Company sold out to the American Metal Company in 1928, operations continued unchanged. However, in the throes of the Great Depression, silver prices in 1931 had dropped to twenty-five cents an ounce.

At one time the town’s population had grown to four thousand and employed five hundred miners, but by the early 1930’s had fallen to around three hundred. President Roosevelt’s economic initiatives had brought about some relief, but the mine closed again in 1942. In 1943, no longer strictly a mining town, Shafter had a population of fifteen hundred. Two nearby military bases, the Marfa Army Air Field and Fort D.A. Russell, were served by the twelve remaining businesses.

When the military bases closed following the end of World War II, the town rapidly declined to less than one hundred residents. In 1954 the Anaconda Lead and Silver Company sent surveyors and prospectors, raising the hopes of locals that mining operations at some level would resume. However, Anaconda left and never return despite finding deposits of high grade lead and silver.

Other attempts to revive and sustain mining operations have been made over the years, the most recent when Aurcana Corporation acquired the Shafter mine in 2008. The company spent a considerable amount of money on equipment and hiring, but by 2013 had scaled back considerably and by year’s end had notified 170 employees of a “permanent layoff”.1

Between 1883 and 1942 the mines yielded 30,290,556 troy ounces of silver, 8,389,526 pounds of lead, and 5,981 troy ounces of gold. With severe water shortages in the region, it seems unlikely the mines could ever again be profitably and responsibly operated. The few remaining residents of the area are served by the Marfa school district about thirty-five miles away. The Cibolo Creek Ranch, located between Marfa and Shafter, was where Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia recently died.

If you’d like to see pictures of the area and what remains of the town, maps and various other historic memorabilia, go to Portal to Texas History and type “Shafter” in the search box. Other sources for this article include: Texas State Historical Association and Ghost Towns of the West, by Lambert Florin, 1973, pp. 667-671. Other articles here at Digging History about this area include: Ghost Town Wednesday: Glenn Springs, Texas and two Tombstone Tuesday articles about a bit of Texas history relating to the Pancho Villa era here and here.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!