This “ghost town” in East Texas is known as the Burning Bush Colony. It was an “intentional community” founded as an offshoot of the Methodist Church. Headquartered in Waukesha, Wisconsin, this splinter group of “Free Methodists” called themselves the “Society of the Burning Bush”, or more formally the Metropolitan Church Association. The organization was funded by two wealthy benefactors, Duke M. Farson and Edwin L. Harvey.

This “ghost town” in East Texas is known as the Burning Bush Colony. It was an “intentional community” founded as an offshoot of the Methodist Church. Headquartered in Waukesha, Wisconsin, this splinter group of “Free Methodists” called themselves the “Society of the Burning Bush”, or more formally the Metropolitan Church Association. The organization was funded by two wealthy benefactors, Duke M. Farson and Edwin L. Harvey.

Farson was a bond broker in Chicago and Harvey a wealthy hotel owner. The group was founded in 1900, citing increased formality of the Methodist Church. Colonies were first established in Virginia, West Virginia and Louisiana. In 1912 the society made plans for a colony in Texas and chose an old plantation near Bullard that had been originally owned by Joseph Pickens Douglas.

The land was purchased in 1907 by Charles Palmer, cultivated and planted with pecan and plum trees. Farson made a deal with Palmer, exchanging the fifteen hundred and twenty acres near Bullard for various properties in Idaho, Illinois and New Mexico. Church administrators arrived in 1912 and set up their headquarters in the mansion.

The land was purchased in 1907 by Charles Palmer, cultivated and planted with pecan and plum trees. Farson made a deal with Palmer, exchanging the fifteen hundred and twenty acres near Bullard for various properties in Idaho, Illinois and New Mexico. Church administrators arrived in 1912 and set up their headquarters in the mansion.

Later that year three hundred and seventy-five church members arrived on a chartered train from the north. They were temporarily housed in the mansion while work began on family homes and dormitory-style buildings for single male and female members. Water and sewage systems were installed and a large wooden tabernacle and school were planned as well.

Church members were required to live communally, eating in a common dining hall and giving up all their worldly possessions upon joining the society. In July of 1905 the society’s publication, called the Burning Bush, advocated that instead of tithing ten percent, adherents were required to give everything to the church:

The reader probably well knows, we preach that we must sell all and follow Jesus. If God permits in this dispensation, for a man to remain on a farm or business, he must give all his earnings to the Lord. The old ‘ten per cent’ is now done away and ‘all’ is the amount to be given to Jesus. Hallelujah, the property once given to Jesus, all Hell is enraged. The Prophet said, he that departed from evil is accounted mad.

There was no type of class system, and though they welcomed visitors onto their property their contact with the “outside world” was limited by choice. Although they used the latest farming equipment available at the time, harvests were unimpressive, apparently due to their lack of knowledge in utilizing southern farming techniques.

Liquor and tobacco were strictly forbidden, yet the only reprisal if caught with the contraband was to take the transgressor to the tabernacle and pray and wail over them, according to the Texas State Historical Association. Their lives in the tight-knit community were centered on work and worship.

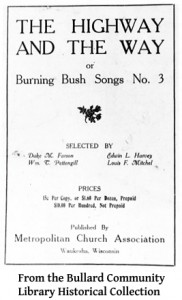

One resident of Bullard, L.B. Lynch, recalled years later his visits to their services as a ten-year old boy: “They rolled on the floor, they hollered a lot, and they stood on the benches when they got religion.” They had their own hymnal as depicted below from Ghost Towns of Texas by T. Lindsay Baker (part of the historical collection of the Bullard Community Library):

Five songbooks were published between 1902 and 1913 and many of the songs were written by church and community leaders. The books cost ten to twenty-five cents a copy, and were sold for several decades.

Five songbooks were published between 1902 and 1913 and many of the songs were written by church and community leaders. The books cost ten to twenty-five cents a copy, and were sold for several decades.

The worship services were intensely emotional. According to the Texas State Historical Association, “one local resident later remembered that the ‘Bushers would turn back flips in church and roll around on the sawdust floor.’ Much of the service was devoted to singing, during which the congregation jumped up and down. Because of this practice, the group was sometimes called the ‘Holy Jumpers.’”

Their original idea had been self-sufficiency, with all they needed contained within their own tight-knit community, but it never happened. With inadequate income derived from the sales of crops, Farson and the Metropolitan Church Association contributed large amounts of money to subsidize the Texas colony. However, it simply was not enough, especially after Farson’s bond business crashed in 1916.

Members began to seek work outside the commune, and as required, turned over one hundred percent of their wages to the church. Still struggling with insufficient funds and inadequate food supplies to remain self-sustaining, the colony began purchasing groceries on credit. The bills piled up and in 1919 the local merchant, J.L. Vanderver, sued for the twelve thousand dollars in outstanding notes.

The county sheriff seized the property and sold it all at a Tyler auction on April 15, 1919 – as it turned out, Vanderver purchased everything for one thousand dollars. Most of the colonists left Texas and returned to the North, although a small contingent remained. Eventually the old mansion and all the Burning Bush Colony buildings were bulldozed. The only remnant left today is a pecan orchard located across the street from Bullard High School.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Did you enjoy this article? Yes? Check out Digging History Magazine. Since January 2018 new articles are published in a digital magazine (PDF) available by individual issue purchase or subscription (with three options). Most issues run between 70-85 pages, filled with articles of interest to history-lovers and genealogists — it’s all history, right? 🙂 No ads — just carefully-researched, well-written stories, complete with footnotes and sources.

Want to know more or try out a free issue? You can download either (or both) of the January-February 2019 and March-April 2019 issues here: https://digging-history.com/free-samples/

Thanks for stopping by!